Pictorialism – Painting With Light

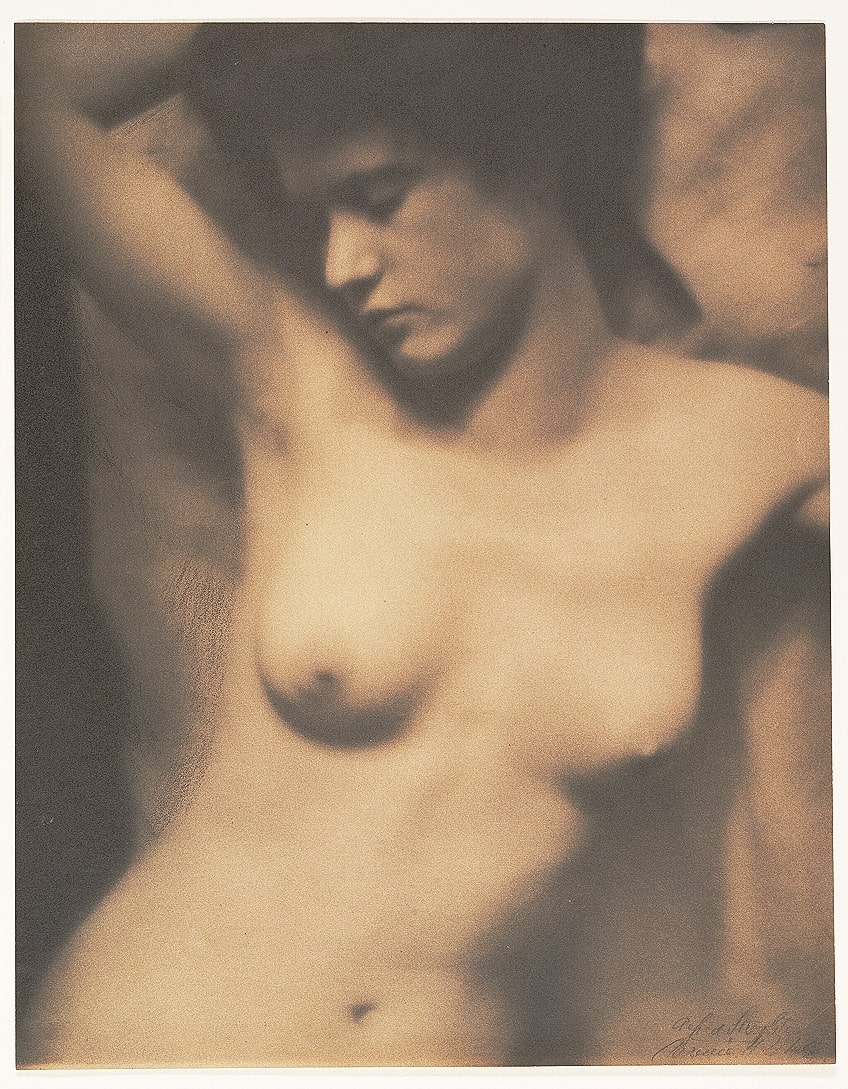

Pictorialism, a pivotal movement in photography’s history, emerged in the late 19th century as photographers sought to elevate their craft to the realm of fine art. Characterized by soft focus, elaborate compositions, and manipulation techniques akin to painting, Pictorialism challenged traditional notions of photography as a purely documentary medium. Led by luminaries such as Alfred Stieglitz, Julia Margaret Cameron, and Clarence H. White, this movement not only revolutionized photographic aesthetics but also sparked debates about the nature of photography as art. In this article, we delve into the origins, key figures, techniques, and the lasting impact of Pictorialism on the art world.

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- Pictorialism advanced photography as an art form by emphasizing aesthetics over documentation.

- Photographers employed creative techniques to produce images with painterly qualities.

- The movement helped to shift the global perception of photography toward artistic legitimacy.

What Is Pictorialism?

Pictorialism represents a pivotal movement in the evolution of photography, marking a departure from pure documentation towards a more artistic expression. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this movement was characterized by the adoption of techniques that would imbue photographs with the qualities typically reserved for traditional fine arts such as painting and etching. It emerged as a response to the prevailing sentiment of the time that photography was a mechanical and not an artistic process. The aesthetic ethos of Pictorialism centered around creating images that emphasized beauty, tonality, and composition.

This was often achieved through manual manipulation of the photograph in various stages of the photographic process, including the shot, the development, or the printing stage. Key figures associated with the Pictorialist movement sought to establish photography as an accepted medium of artistic expression, thus broadening the understanding and perception of the art form on a global scale. Pictorialism illustrates the camera’s potential as an artistic tool, not just a recording device.

It played a critical role in establishing photography as a legitimate fine art form, on par with more established mediums.

However, the movement began to decline around 1915, as some prominent figures started advocating for Straight Photography, a style emphasizing sharp focus and the unmanipulated portrayal of subjects. Key characteristics of pictorialism included:

- Artistic expression: Photographers aimed to express personal artistic vision rather than merely document reality.

- Techniques: The use of soft focus, special filters, and darkroom manipulation were common to achieve the desired artistic effect.

- Subject matter: It focused on evocative, sometimes romantic or pastoral subjects, rendered to mirror the style of paintings.

Historical Context and Key Figures

In tracing the narrative of Pictorialism, several essential artists, societies, and publications emerge, each contributing significantly to the movement’s ethos and development.

Origins and Influential Artists

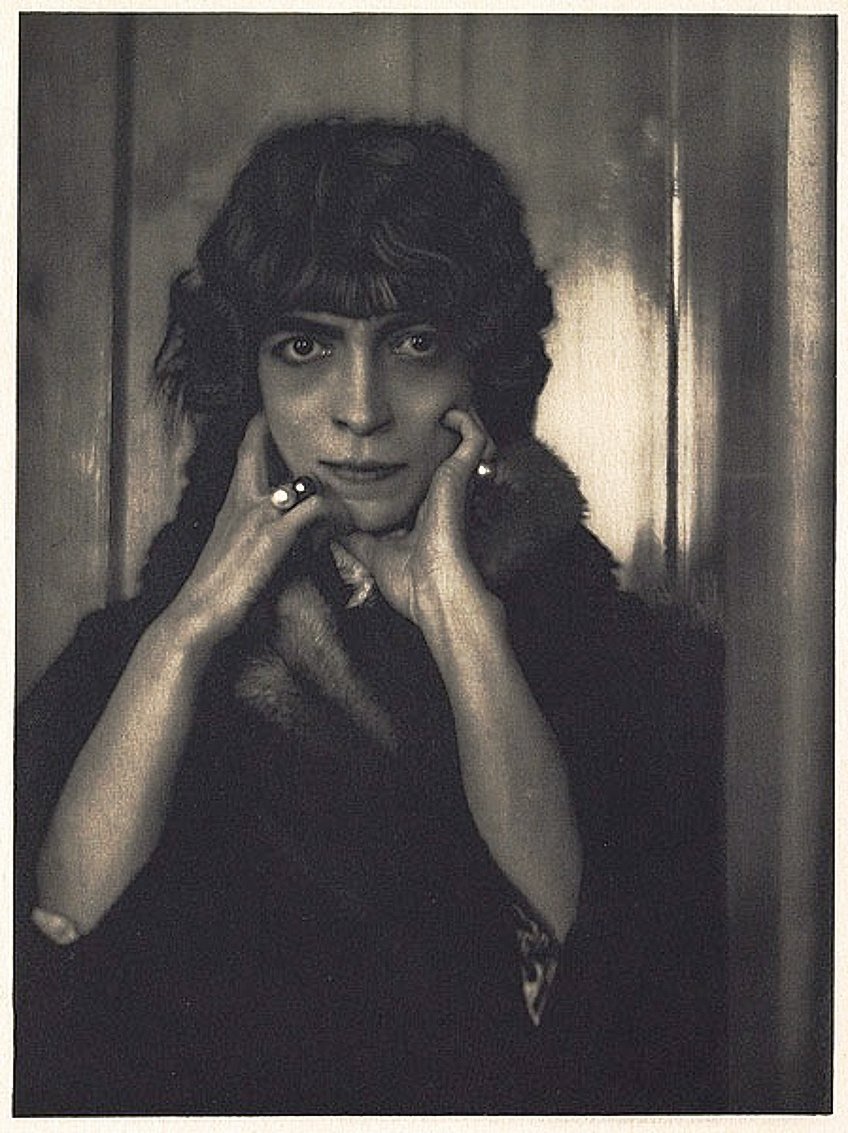

Pictorialism began in the late 19th century, spearheaded by photographers who aimed to elevate photography to the status of fine art. Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen were pivotal, advancing the aesthetic of carefully crafted images. Henry Peach Robinson was another early proponent, known for creating composite images to convey a narrative. Julia Margaret Cameron is celebrated for her expressive portraits, and partners David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson laid early groundwork with their notable calotypes.

Pictorialist Societies and Journals

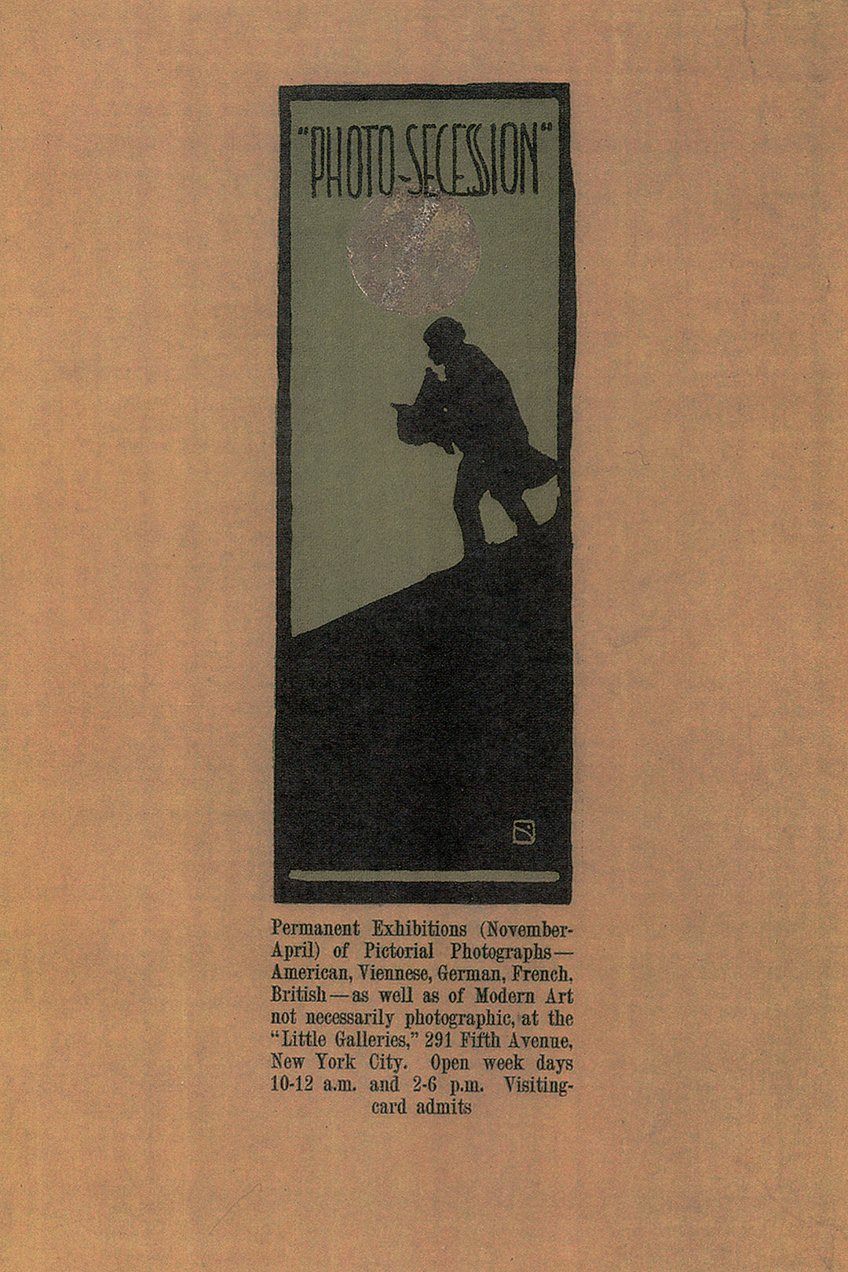

Groups like the Linked Ring in the UK and the Photo-Secession in the US, led by Stieglitz, actively promoted Pictorialism through exhibitions and publications. The Photo-Club de Paris and the Royal Photographic Society were also instrumental.

Journals like Camera Work provided a platform for disseminating Pictorialist images and ideology, becoming a beacon for artists like Gertrude Käsebier and Clarence H. White.

Key Ideas and Accomplishments

The hallmark of Pictorialist photography was the manipulation of images to express an aesthetic vision. This often involved soft focus, special printing processes, and darkroom alterations. The movement’s figureheads achieved substantial acclaim through these methods, with F. Holland Day, James Craig Annan, and George Davison being notable contributors. The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession showcased these artists’ works, further demonstrating the movement’s technical and artistic advancements.

Notable Exhibitions and Legacy

Pictorialism’s legacy was cemented by significant exhibitions, such as those at the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, known later as 291 after its address. Here, Stieglitz and others showcased avant-garde art, including Pictorial photography. The movement also influenced later artists and styles, forming the foundation for modern art photography.

As new techniques and attitudes emerged, particularly with the advent of Straight Photography, Pictorialism’s influence persisted in the emphasis on personal expression within the photographic medium.

Beginnings of Pictorialism

Pictorialism marked the recognition of photography as an art form, emphasizing aesthetics and self-expression. It evolved from mid-to-late nineteenth century into the early twentieth century, challenging the medium’s purely documentary role.

Early Pioneers

Early figures like Julia Margaret Cameron, David Octavius Hill, and Robert Adamson were instrumental in Pictorialism’s foundation. They explored beyond photography’s immediacy to focus on artistic qualities, garnering attention for creative composition and expression within the nascent art form.

The Photo-Secession

The Photo-Secession, led by Alfred Stieglitz in the early 1900s, was a critical moment that further legitimized Pictorialism. This group of photographers was keen on advocating for photography as a medium capable of artistic mastery on par with traditional arts.

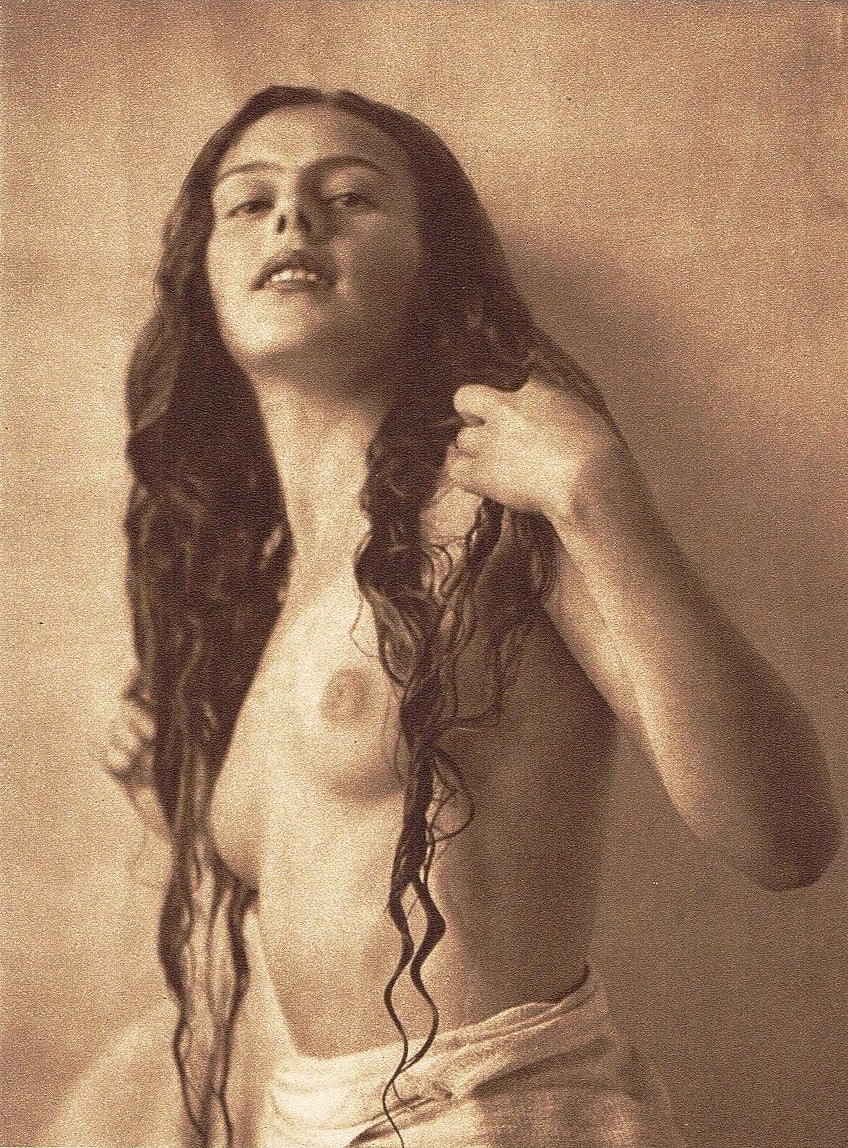

Pictorialism, Tonalism, and Impressionism

Pictorialism drew parallels with Tonalism and Impressionism in painting, focusing on mood and atmosphere. The movement’s photographers used soft focus and played with light and shade to echo these painterly techniques.

Composite Images

Pictorialists created composite images by combining multiple negatives or manipulating a single one. This technique allowed for more control over the image, much like a painter controls a canvas, to evoke particular themes or narratives.

The Development of Gum Bichromate and Color Processes

Advancements such as gum bichromate and other color processes were embraced by Pictorialists to expand their artistic range. These processes enabled the introduction of texture and color variations, further distancing photography from its initial, purely documentary function.

Technical Aspects and Aesthetics

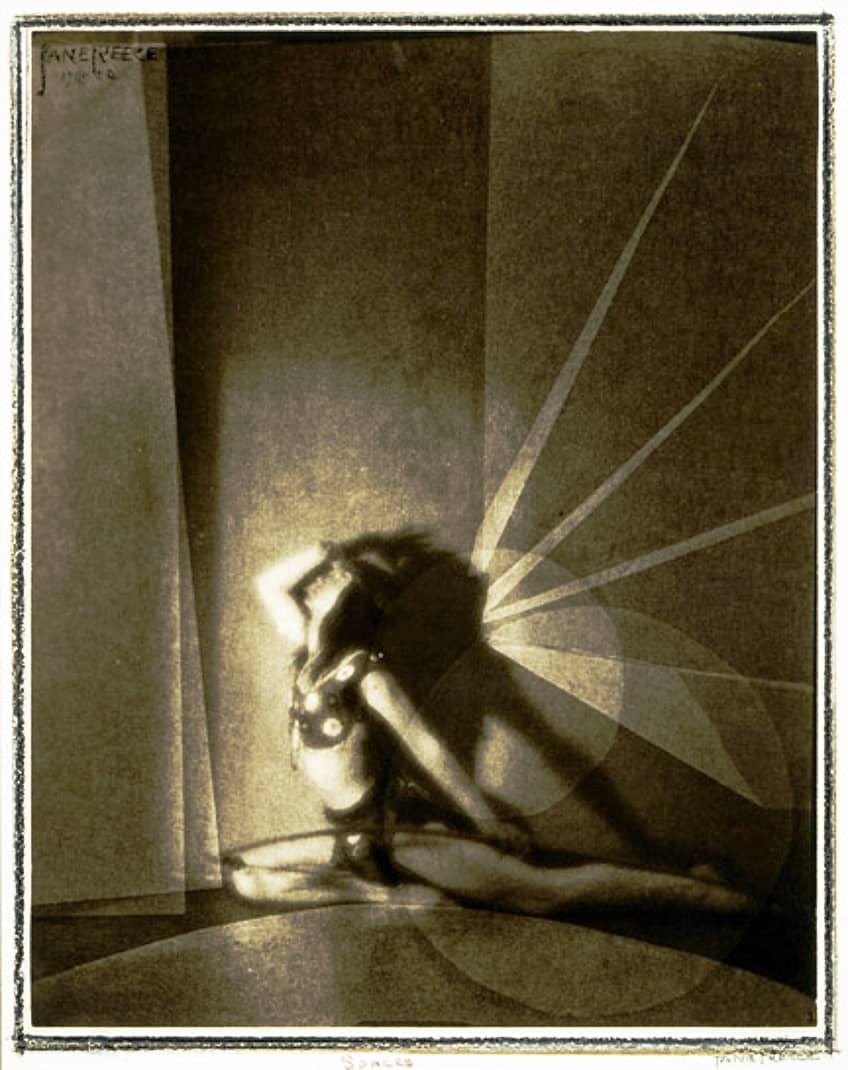

Pictorialism was marked by its dedication to craftsmanship in the creation of photographic art, with an emphasis on the manipulation techniques and composition that elevated images to a realm of artistic expression.

Photographic Techniques and Composition

Pictorialists employed a range of photographic techniques to achieve artistic effects akin to painting. They often used soft focus to imbue images with a dreamy, less literal appearance, merging photography with the realm of fine art.

Composition played a pivotal role, with careful arrangement of subject matter to evoke an aesthetic value rather than simple documentation.

Key techniques used included:

- Soft focus: Achieved using special lenses or filters.

- Hand-coloring: Adding colors to prints.

- Manipulation of negatives: Adjustments to enhance visual beauty.

- Staging of scenes: Constructed for narrative or atmospheric effect.

Printmaking Methods and Materials

The choice of printmaking methods and materials was instrumental in differentiating Pictorialist photos. Platinum prints were favored for their long tonal range and gum bichromate was used for its painterly qualities. These materials allowed Pictorialists to resemble the appearance of ink or paint on canvas. Common printmaking techniques were:

- Gum bichromate: A method allowing the use of watercolors or pigments.

- Platinum printing: Produced images with rich gradations of tone.

The use of these techniques and materials meant Pictorialists often rejected the growing popularity of Kodak and other handheld amateur cameras of the time, which promoted candid snapshots. Through mastery of process and perception, Pictorialists reinforced the idea of the camera as a tool capable of yielding art, rather than mere mechanical reproductions.

Pictorialism in the Context of Global Photography

Pictorialism was a significant movement that transformed the aesthetics and perception of photography on an international level, forming a bridge between early photographic processes and modern visual art forms.

International Reach and Camera Clubs

Pictorialism transcended national boundaries, flourishing through camera clubs and journals worldwide. These clubs were the nuclei of the movement, bringing together like-minded individuals passionate about the artistic potential of photography. They fostered an environment of collaboration and learning, and aided in the spread of Pictorialist aesthetics by holding exhibitions and competitions.

Key to this dissemination were influential publications such as Camera Work, a journal started by Alfred Stieglitz, which showcased Pictorial photography and discussions on its role in fine art. Notable camera clubs included:

- The Photo-Secession in New York

- The Linked Ring in London

- The Photo-Club de Paris

Transition to Modern Photography

Post-World War I, the Pictorialist movement saw a decline as photographers began to explore new perspectives. Innovators like Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, and Paul Strand contributed to the shift from Pictorialism’s soft-focus and allegorical subject matter to a more naturalistic and sharp-focused imagery. This new phase, often referred to as Straight Photography, favored straight, uncropped images with higher contrast and clarity, focusing on the inherent qualities of the camera rather than hand-manipulated prints.

The advent of the Kodak camera also democratized photography, leading to a rise in snapshots by amateur ‘snapshooters’, contrasting the meticulous printing methods of Pictorialists.

Key aspects leading to transition included:

- Increased emphasis on naturalistic photography

- Desire for sharp focused images

- Popularity of Kodak cameras and snapshot photography

Cultural Impact and Artistic Movements

The advent of Pictorialism marked a significant turn in the history of photography, fostering close relationships with other artistic movements and leaving an enduring impact on various art forms. Its influence can be traced through modernism, post-pictorialist trends, and its lasting legacy in today’s artistic expressions.

Pictorialism and Modernism

Pictorialism arose during the late 19th century, parallel to the evolving movement of Modernism. It shared with Modernism a desire for personal expression and a departure from mere visual records. Pictorialists injected an artistic spirit into photography by creating images with a pictorial effect, using soft focus and compositional techniques reminiscent of painting.

This integration of photography as an art form saw its full realization through exhibitions, which served as platforms for Pictorialist photographers to share their artistic vision with a broader audience.

After Pictorialism

As the 20th century progressed, Pictorialism’s influence waned, overtaken by new photographic practices that emphasized clarity and detail—hallmarks of the Modernist ethos. These practices were not just limited to photography but also encompassed other visual disciplines like sculpture, wherein Pictorialism’s romantic and emotional intent laid the groundwork for more abstract forms of expression.

Influence on Later Art Forms

Pictorialism’s aesthetic movement played a substantial role in the development of fine art photography. By highlighting the medium’s potential for personal expression and visual beauty, Pictorialism paved the way for subsequent photographers to explore beyond the documentary and delve into the more subjective aspects of the medium.

Its methods, including chiaroscuro and tonalism, have influenced various art forms, contributing to the growth of artistic photography as an international style.

Legacy of Pictorialism Today

In contemporary times, the legacy of Pictorialism persists in the continued appreciation of the medium’s expressive capabilities. The movement’s pioneering vision fostered a perception of photography not just as a mechanical process, but as a legitimate and versatile art form—a notion that is widely embraced in current artistic and exhibition environments. Pictorialism is recognized for its integral role in the international movement toward acknowledging photography’s place alongside painting and sculpture in the pantheon of fine arts.

Pictorialism stands as a testament to the artistic potential of photography and its capacity to transcend mere representation. Despite its decline in popularity with the rise of modernist and documentary approaches, the legacy of Pictorialism endures in contemporary photographic practices. Its influence can be seen in the ongoing exploration of photography’s expressive and subjective qualities, reminding us of the enduring allure and relevance of this transformative movement in the history of art and photography.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Defining Characteristics of Pictorialist Photography?

Pictorialist photography is distinguished by its focus on aesthetic qualities, such as beauty, tonality, and composition. Pictorialists often manipulated their images to create a sense of atmosphere and emotion, prioritizing artistic expression over the mere documentation of reality.

How Did Pictorialism Influence the Art World in Its Time?

During its prominence from the late 19th century to around 1914, Pictorialism challenged the confines of traditional art, asserting photography’s place as a fine art on par with painting and sculpture. It formed an international movement with camera clubs and societies advocating for the creative potential of photography.

What Techniques Were Commonly Used by Pictorialist Photographers?

Pictorialists frequently used soft focus techniques, darkroom manipulation, and various printing processes to evoke a painterly quality in their works. Such methods differentiated their photos from the sharp, unaltered depictions typical of other photographic styles of the era.

How Does Pictorialism Differ from Straight Photography in Its Approach?

Unlike Straight Photography, which emphasized unmanipulated images with clear focus and a factual representation of the subject, Pictorialism embraced manipulation and artistic intervention. Pictorialist photographers aimed to imbue their images with emotional depth and an individual artistic vision.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Pictorialism – Painting With Light.” Art in Context. April 15, 2024. URL: https://artincontext.org/pictorialism/

Meyer, I. (2024, 15 April). Pictorialism – Painting With Light. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/pictorialism/

Meyer, Isabella. “Pictorialism – Painting With Light.” Art in Context, April 15, 2024. https://artincontext.org/pictorialism/.