Gardner Museum Heist – The Story of the Notorious Art Robbery

Ever wondered what the greatest art heist of the 1990s was? If art heists are your favorite subject, then stick around to find out more about the notorious $500 million heist that took place at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1990. The renowned museum even offered a $10 million reward for the recovery of many legendary artworks that were snatched, including iconic works by Rembrandt and Vermeer. You may have even spotted the 2021 docuseries on Netflix titled This is a Robbery, which had many viewers intrigued. In this article, we will provide you with a complete summary of the world’s biggest art heist!

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Heist

Recognized as one of the most legendary art heist investigations to date, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist is one that shook the art world. In 1990, approximately 13 artworks were finessed out of the museum, leaving the case unsolved and many high-value works still missing. 18 March, 2023 marked the 33rd anniversary of the art heist that not only inspired a four-part documentary in 2021, but was also the hot topic on the FBI podcast released in June, 2023.

The reward for the missing artworks currently stands at $10 million with the value of the stolen artworks valued at more than $500 million.

How did these mysterious thieves manage to pull off one of the most notorious acts of all time? Who are these masterminds? Where are the stolen artworks? Below, we will dive into the nitty gritty details surrounding the heist and some of the recent theories about the most likely suspects.

Dawn of the Heist

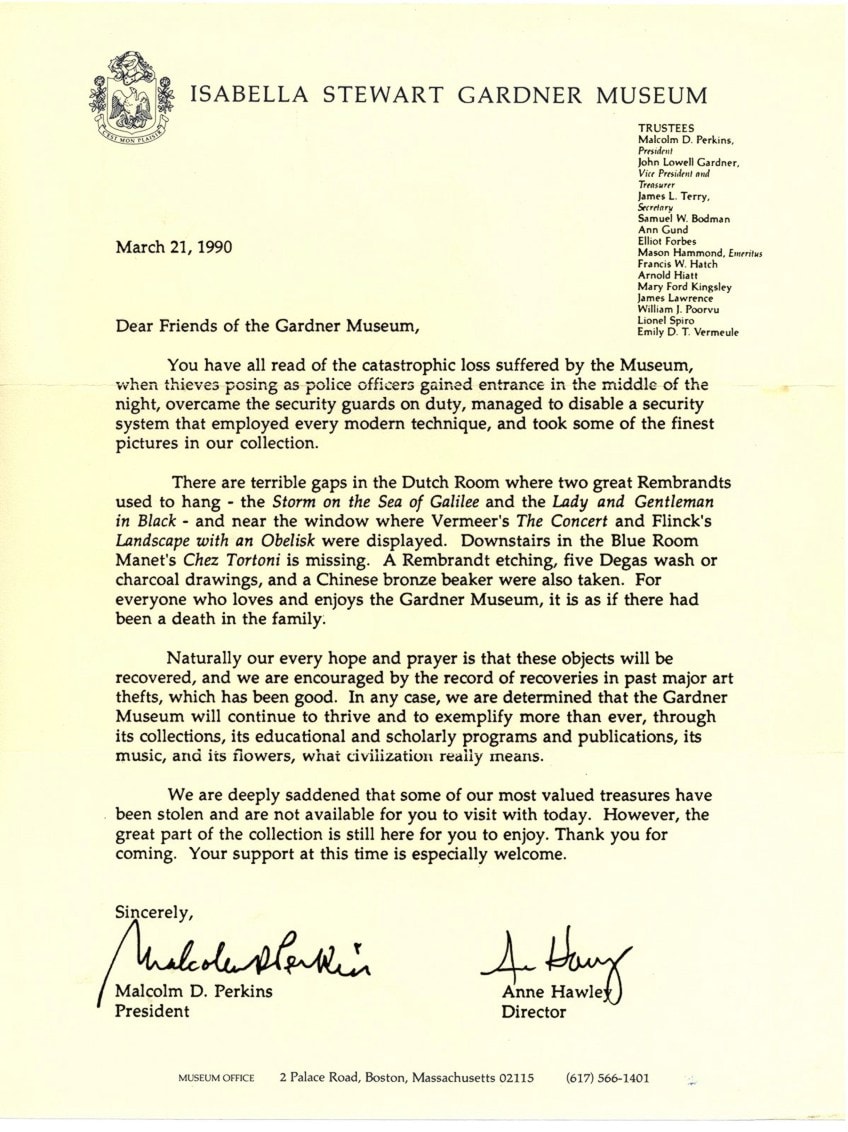

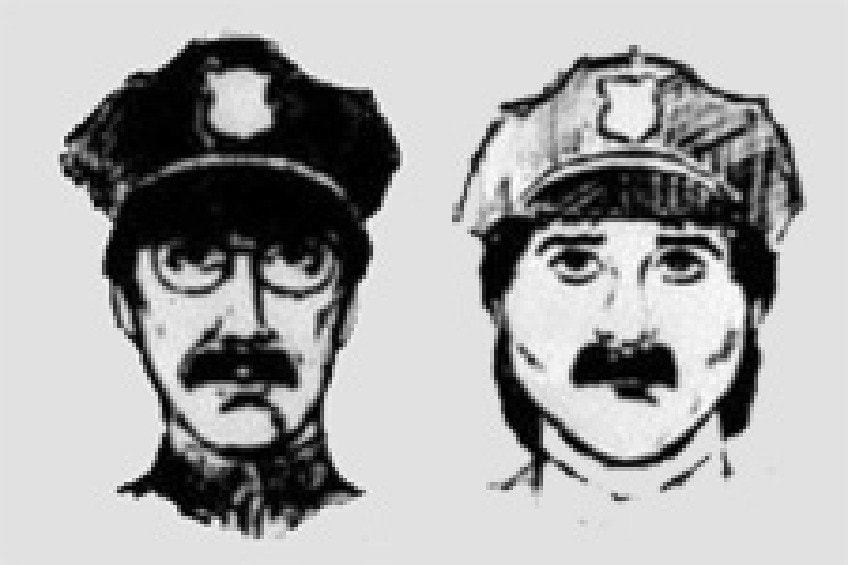

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist occurred on March 18 in 1990 in the early hours of the morning. According to reports from the two guards who were on duty, they had seen two police officers, who were in fact criminals, in disguise, claim to respond to a “distress call” in the area. With no second thought, the guards assumed that this routine would be a clear-cut inspection and decided to let them through the employee entrance.

According to the report from the museum, one of the guards had, in fact, broken the museum’s protocol by allowing the officers to enter through the employees’ entrance.

Within no time, both security guards were handcuffed and locked in the basement. 81 minutes later, the thieves successfully accomplished their mission and made off with 13 artworks. The remaining traces of the thieves’ activities in the museum were documented by the motion detectors in the museum.

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Context

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum was established after the art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner, who amassed a large art collection in her name. The museum opened its doors in 1903 and had since grown its collection. After the death of Gardner, the institution was left with a $3.6 million endowment from the collector’s will, stating that the organization of the artwork was not to be altered and no artworks or objects from the collection were to be purchased or sold.

Around the 1980s, the museum saw a decline in its financial health, which resulted in a lack of maintenance around the building’s climate control and basic facilities. At this point, the museum was also short of an insurance policy, thus making it quite vulnerable.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) discovered a conspiracy by local Boston criminals to loot the museum and issued an alert to the museum in 1982. The museum had no choice but to ramp up its security and installed 60 infrared motion detectors with a closed-circuit TV system containing four surveillance devices around the museum’s perimeter. Unfortunately, no cameras were installed in the interior of the building since this was a costly option for the board of trustees at the time.

In an effort to balance this lack of security, the museum hired more guards and installed a button at the front desk to call the police in cases of emergency. A common security feature for other museums at the time was a fail-safe system, which involved the night guards placing hourly phone calls to the police to inform them that the museum was secure.

In retrospect, this would have been a better system for the museum, however, a review by an independent security consultant stated that the museum was “up to scratch” with its security, but could still use more improvements.

By 1988, the museum’s finances were even more dire and at some point, even the security director from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts recommended inputs for a security upgrade. Unfortunately, the requests were denied, along with the salary raise for the security guards in hopes of attracting qualified applicants. This implied that the position was occupied by those who were not necessarily fit for emergency situations such as an armed heist.

Details on the Day of the Heist

After subduing the guards in under 15 minutes and issuing threats, the thieves moved on to execute their heist at 01:35 in the morning. The thieves’ movements were first recorded in the Dutch Room, which was on the second floor, around 01:48 A.M.

From the time stamps, the police assumed that the thieves were most likely waiting to make sure no one was coming to catch them.

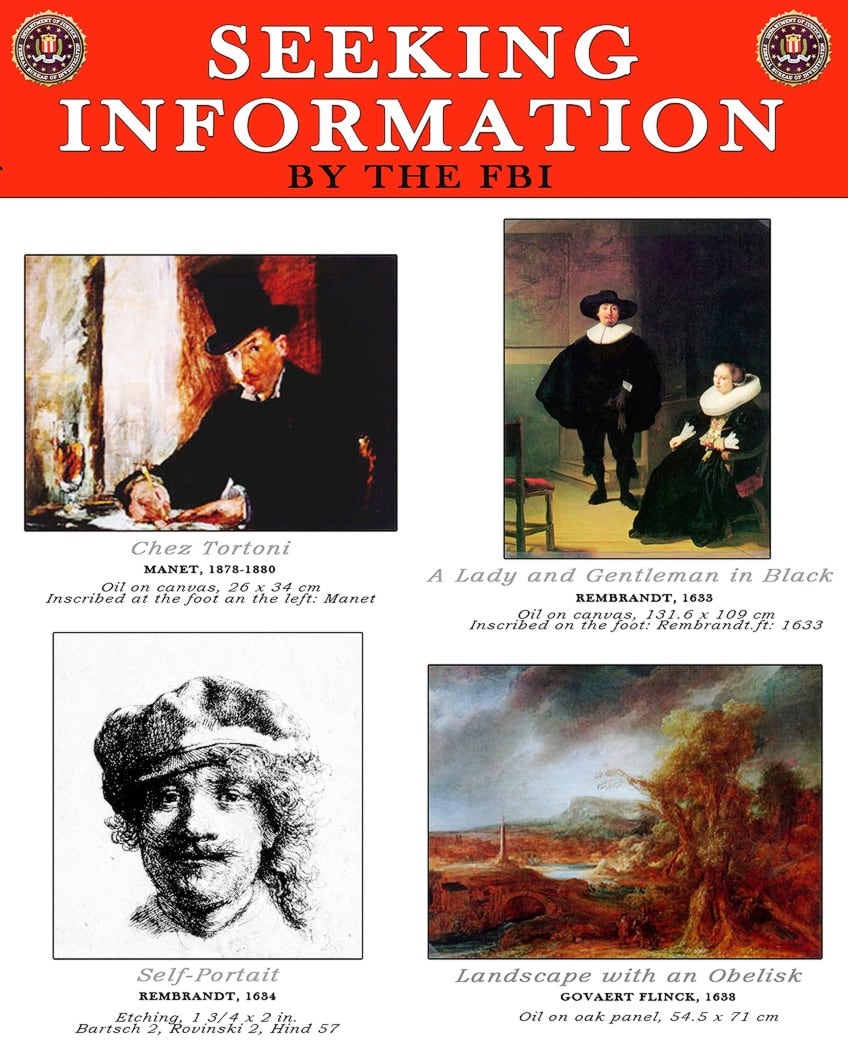

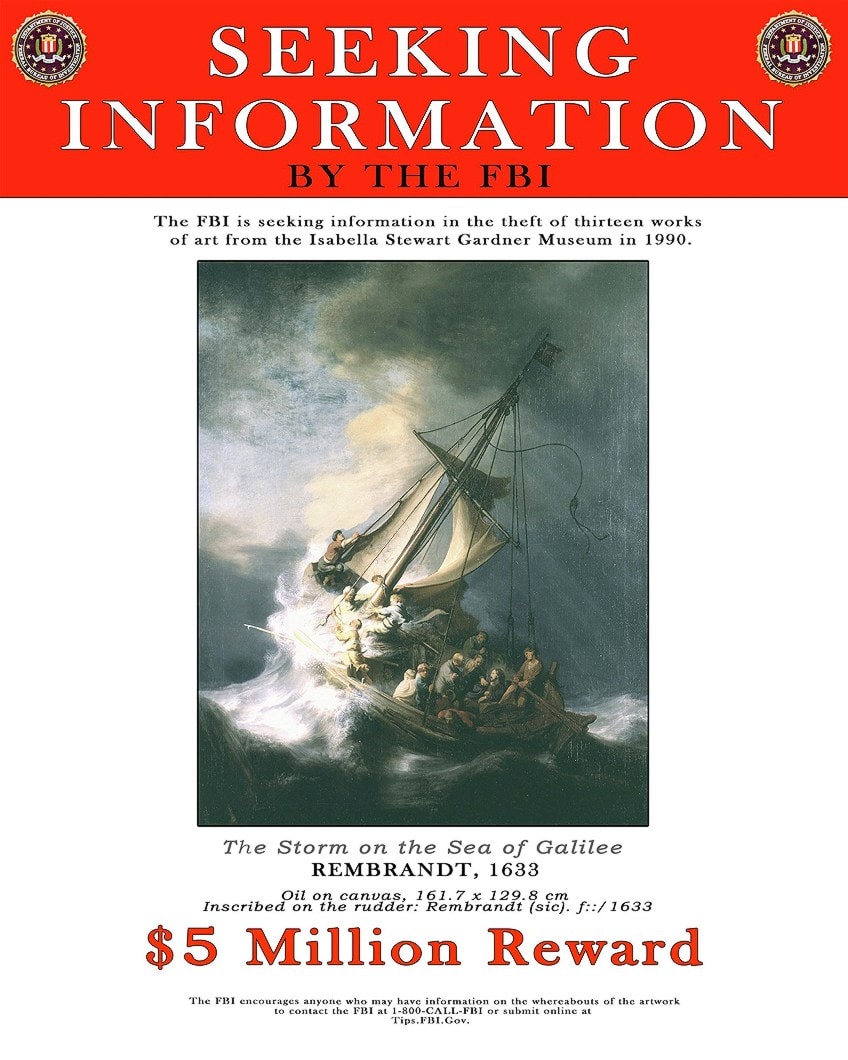

When the criminals approached the paintings, the warning alarm for people who stood too close to the artworks went off, but the thieves halted it by destroying the system. From the Dutch room, the thieves stole a painting by Rembrandt van Rijn titledThe Storm on the Sea of Galilee (1633). To accomplish this, they smashed the painting on the marble floor to destroy the glass frame and removed the canvas from the stretcher using a blade.

Along with this Rembrandt painting, they also took a self-portrait, but ended up abandoning it against a cabinet, presumably due to it being too large to transport. In place of this, they stole a mini self-portrait by Rembrandt, which was exhibited under the large one.

The thieves’ choices were considered targeted and informed since it was clear that the thieves knew of the value of a Rembrandt artwork.

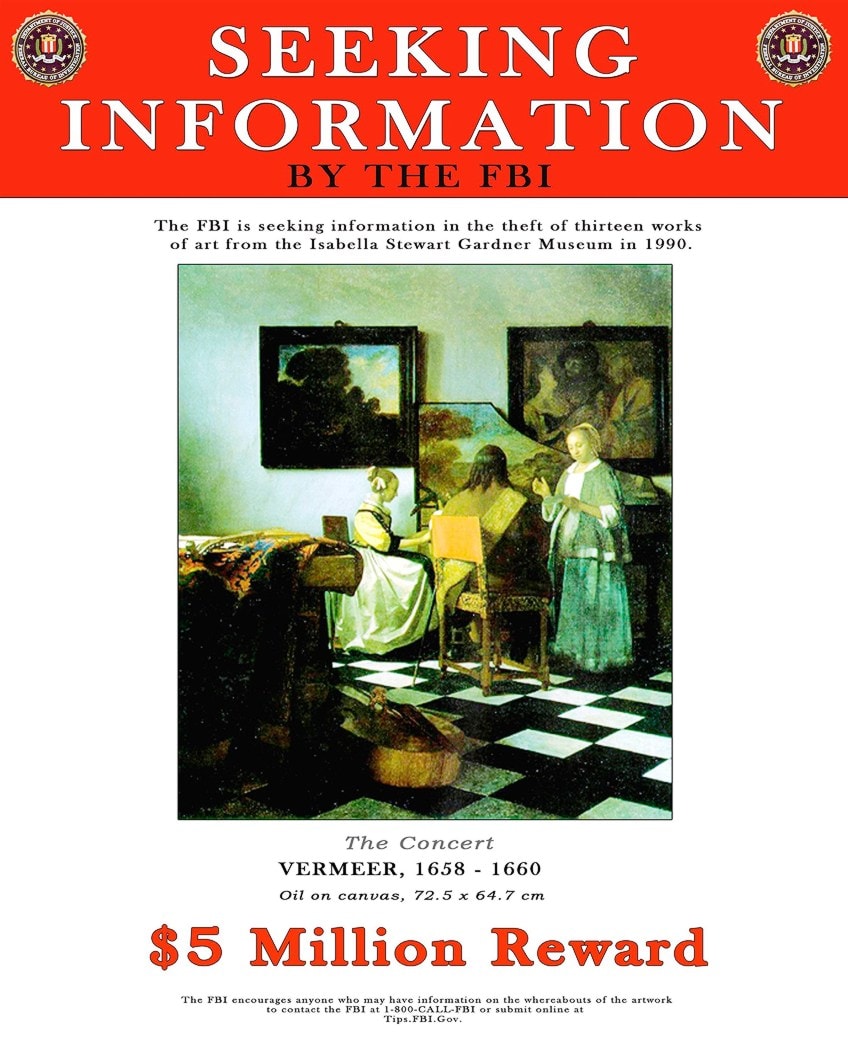

Other works taken from the Dutch Room include The Concert (1664) by Johannes Vermeer, Landscape with Obelisk (1638) by Govert Flinck, as well as a Chinese gu (vessel). The thieves then split up and one of them entered the Short Gallery, which was located on the far end of the second floor.

After the one thief completed their mission in the Dutch Room, they joined their accomplice in the Short Gallery, where the duo attempted to steal the Napoleonic flag.

They did not succeed in this effort but they did steal the eagle finial, which was mounted on the pole of the flag. Here, they also grabbed five sketches by Edgar Degas and another famous artwork from the Blue Room called Chez Tortoni (1875) by Édouard Manet.

Before the heist ended, the thieves went back to check on the guards to ensure that they were comfortable. This interaction pointed to the idea that the thieves intended on only grabbing the artworks as efficiently as possible, without inflicting harm. The thieves also bagged the video cassettes that contained a record of their entrance and data print-outs from the motion detectors.

However, this valuable information still remained on the system’s hard drive, which was left behind.

It is assumed that Chez Tortoni was the last artwork to be snatched since the painting’s frame was found abandoned at the security director’s desk. The dynamic duo then moved the artworks out of the museum between 02:40 and 02:45. The security guards who showed up later that morning for their shift discovered the precarious situation and called the security director, who then showed up at the museum and called the police after noticing the missing security guards.

The police arrived on the scene and searched the building, where they found the guards tied up in the basement.

Stolen Artworks and Values

A total of 13 artworks were stolen in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist and in 2000, the estimated value of the missing works rose from $200 million to $500 million. Later that year, the value was estimated to be around $600 million.

Considering the amount of time that has passed since the heist, the value of the artworks is said to have certainly climbed.

The artworks stolen from the Dutch Room were considered the most valuable with Vermeer’s painting The Concert sitting at an estimated $250 million. The thieves aimed to steal very specific works, as seen in the theft of Rembrandt’s only existing seascape, The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, which had an estimated worth of $140 million.

The small self-portrait of Rembrandt had already been stolen twice before and was returned once in 1970, only to be stolen again in 1990.

The other stolen painting by Rembrandt was A Lady and Gentleman in Black (1633). It is believed that the thieves stole the Landscape with Obelisk (1638) by Govert Flinck believing that it was also the work of Rembrandt. The other art object, the Chinese gu, was known to be one of the museum’s oldest artworks that dated back to the 12th century Shang Dynasty era but carried a smaller value of around several thousand dollars.

All the sketches by Degas that were taken were all works on paper executed in charcoal, ink, pencil, and washes. The total combined value of these drawings was calculated to be worth $100,000. The 25-centimeter-tall Imperial Eagle from the Napoleon Imperial Guard’s flag was also stolen.

The museum currently offers a separate reward of $100,000 for any information on the object’s return.

Experts who reviewed the thieves’ selection of artworks were left confused since they stole a combination of artworks of varied values and overlooked other high-value artworks by masters such as Michelangelo and Raphael.

Was this an intentional tactic?

The thieves never crossed the third floor where the most valuable painting hung, The Rape of Europa (1560-1562) by Titian. Today, the missing works’ empty frames remain in their original places, awaiting their respective returns. The table below shows a list of the stolen artworks, which may give you insight on the minds of the thieves and their selections for the heist.

| Artist | Stolen Artwork(s) |

| Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (1606 – 1669) | Christ in the Storm on the sea of Galilee (1633); A Lady and Gentleman in Black (1633); Portrait of the artist as a Young Man (c. 1633) |

| Govaert Teuniszoon Flinck (1615 – 1660)

| Landscape with an Obelisk (1638) |

| Johannes Vermeer (1632 – 1675)

| The Concert (1663 – 1666) |

| Edgar Degas (1834 – 1917) | Leaving the Paddock (c. 19th century); Procession on a Road near Florence (1857 – 1860); Study for the Programme (1884); Study for the Programme De La Soirée Artistique Du 15 Juin 1884 (1884); Three Mounted Jockeys (1885 – 1888) |

| Pierre-Philippe Thomire (1751 – 1843)

| Eagle Finial (1813 – 1814) |

| Édouard Manet (1832 – 1883)

| Chez Tortoni (1875) |

| Unknown Artist | Chinese Gu (12th century) |

Suspects and Leads

Since the statute of limitations expired in 1995, prosecutors stated that anyone who willingly returned the stolen artworks, and who partook in the 1990 art heist, would not be prosecuted. The FBI assumed control of the case due to the concern that the artworks had great potential to have been transported across state lines. The thieves committed a “clean” heist and left behind no traces of DNA or prints for police to analyze. With the waiver to not prosecute the criminals, there had also emerged numerous theories around the heist, including the reasons why no one emerged to return the works or take accountability.

The fingerprints at the scene were especially unreliable since the evidence was inconclusive as to whether they were the employees’ fingerprints or the thieves.

Witnesses in the area provided a description of the criminal they thought to be approximately 1.75 to 1.78 meters tall, in his late 30s with a solid build. Some of the suspects, as mentioned below, have been investigated, but none have proven spot-on.

Among the suspects investigated include one of the security guards present at the heist, Rick Abath, the leader of the Winter Hill gang, Whitey Bulger, Brian McDevitt, Carmello Merlino, and Robert Guarente, who was also identified as Bobby Guarente.

Bobby Donati

One of the theories about who executed the heist was said to be Bobby Donati, an American criminal who was murdered in the same year during a gang war with the Patriarca family. Donati was flagged as a suspect after the famous art thief Myles J. Connor Jr. conversed with the authorities and dropped Donati’s name while in prison.

He also claimed that he allegedly collaborated with Donati on past heists and suggested that Donati was particularly interested in the “Finial Eagle”.

Connor Jr. also theorized that Donati hired “lower-level criminals” to execute the heist. Connor Jr. wished to help the authorities with the case in exchange for his freedom but this was never on the cards for the authorities. The FBI were then redirected to an antique art dealer (and criminal) known as William P. Youngworth.

The FBI raided Youngworth’s store and home in the 1990s, which drew in the journalist Tom Mashberg, who had an interest in the art dealer. In August of 1997, Youngworth summoned the journalist on the claim that he had proof that he could return the missing works but under specific and controlled conditions. According to Mashberg, Youngworth took him to a warehouse in Red Hook, Brooklyn, where he showed him a storage unit containing several tubes. Youngworth then opened one of the tubes and showed him a canvas, which Mashberg identified as Rembrandt’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee.

He also caught Rembrandt’s signature on the ship’s rudder and cracking on the edges of the canvas, which in his eyes, appeared to be the real deal.

Mashberg published his experience in the Boston Herald, and after several months, the FBI discovered no traces of any tubes or artwork at the storage unit. Youngworth also left Mashberg with paint chips that curiously matched paint from Rembrandt’s era, however, they were not the same oil paints used in Rembrandt’s painting.

The painting was also coated with a heavy layer of varnish and could not have been rolled up as easily as Mashberg described it.

The FBI began negotiating with Youngworth but he refused to comply unless his demands were met, which included immunity and Connor’s freedom. The authorities pressed him for proof, which led to more paint chips from the 17th century, as well as color photographs. The paint chips did not match Rembrandt’s painting, but could have very well been from Vermeer’s The Concert.

Fast forward to 2014, investigative reporter Stephen Kurkjian inquired with one of Donati’s superiors, Vincent Ferrara, who stated that the FBI was wrong for suspecting Merlino’s gang and that Donati was the one who organized the heist. He further stated that Donati visited him in jail three months before the heist and promised him that he was going to “do something” to get Ferrara out of jail. Exactly three months later, Ferrara heard the news about the Gardner Museum heist, after which Donati paid him another visit claiming that he was definitely involved and that he had buried the artworks. His plan was to begin negotiations once the investigation “cooled down” but this never happened because Donati was murdered.

So far, all hands and testimonies pointed to Donati, who was no longer alive, thus leaving authorities with another dead end.

Jimmy Marks

Recent developments on the case revealed a potential accomplice or affiliate to the heist. In 1991, a man named Jimmy Marks was murdered, and years later, it was discovered that his death may have been linked to the 1990 Gardner heist. The case went cold but since then new clues emerged that could lead to the thieves, as stated by Bob Ward.

The FBI stated that the stolen artworks probably moved through various organized crime circles in Philadelphia, but the trail went cold around 2003. The chief of security at the Gardner Museum, Anthony Amore, received a tip from an anonymous person urging the officials to investigate the murder of Jimmy Marks, who was a famous career criminal.

Marks was murdered 11 months after the heist on a February evening while entering his apartment in the suburb of Lynn, Massachusetts. The perpetrator unscrewed the light above the door so that Marks could not see and shot him in the “classic mob style hit”. Marks was shot twice in the back of his head.

Before Marks was killed, it had been reported that he was bragging about being in possession of two stolen paintings, as well as claims that he had other artworks stowed away. Marks was also previously involved in a bank robbery around the 1960s and was a known drug dealer.

The possibility that Marks knew of the real identity of the thieves or whoever organized the heist was significant since he already had connections to certain individuals who were suspected of being involved at the time.

According to news reports, Marks was acquainted with the late Robert Gaurente (Bobby), who was good friends with Donati and may have partaken in the transportation of the stolen artworks from Boston to Connecticut to Philadelphia.

Robert Gentile

In 2015, the case gained further insight into Marks’ involvement after Gaurente’s widow declared that her husband killed Marks. Gaurente passed away in 2004 and later on, his widow passed away in 2018. According to reports on the account, Guarente’s widow appeared very emotional when speaking about Marks.

During this time, another suspect was called out by Gaurente’s widow, Robert Gentile, who was a Connecticut gangster with a long criminal record.

In 2012, after many lies and denials by Gentile, the FBI raided his home and used ground-penetrating radar equipment to discover mostly drugs and guns. In a raid of Gentile’s Manchester home, the FBI found a list of the stolen artworks with their black-market value but nothing else. Gentile states his innocence multiple times regarding knowledge of the paintings but according to some, and the Gardner Museum, there are still individuals who believe that he was the last missing link. Gentile passed away in September 2021.

Another account by Paul Calantropo details how Donati met him in the Spring of 1990. Calantropo was an old school friend of Donati’s and an appraiser of jewelry. According to Calantropo, Donati visited him to show him the Finial Eagle and request its worth. Calantropo was allegedly stunned and recognized the bronze object as one of the famous stolen artworks from media reports. The former Assistant US attorney, Robert Fisher, who supervised the heist investigation from 2010 to 2016, did not believe Calantropo’s story and stated that until the stolen artworks were found, every theory was still “just a theory” and that more proof was needed to make Donati the prime suspect. A former convict who entered into an agreement with the museum claimed the opposite. He claimed that Calantropo’s story was true, that Donati trusted no one, and that he believed that Donati buried the artworks such that “one day someone was going to open up a wall and find them”.

The case of the 13 missing artworks continues to be a sensational investigative affair for many art heist theorists. Only time will tell where the missing artworks are and who was responsible for the 1990 Isabella Stewart Gardner heist. For now, one can only theorize and speculate as to the possibilities for where these missing masterpieces are and what the next clue might be.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Many Artworks Were Stolen During the 1990 Gardner Heist?

Approximately 13 artworks were stolen during the 1990 Gardner heist. These include highly valuable paintings by Rembrandt van Rijn, Govaert Flinck, Johannes Vermeer, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Philippe Thomire, and Édouard Manet. Along with these artworks, an ancient Chinese vase and a bronze filial eagle was also taken.

What Is the Value of the Missing Artworks From the 1990 Gardner Heist?

The missing artworks from the 1990 Isabella Stewart Gardner heist are said to be valued at between $500 million and $600 million. The most valuable missing paintings account for approximately half the total value of stolen artworks.

Who Were the Lead Suspects in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Heist?

The lead suspects in the Isabella Stewart Gardner heist were Bobby Donati and Robert Gentile along with other possible unidentified accomplices. The latter suspect, Robert Gentile is no longer at the forefront of the investigation, although some still believe of his involvement. Today, there is no solid proof around a prime suspect.

Nicolene Burger is a South African multi-media artist, working primarily in oil paint and performance art. She received her BA (Visual Arts) from Stellenbosch University in 2017. In 2018, Burger showed in Masan, South Korea as part of the Rhizome Artist Residency. She was selected to take part in the 2019 ICA Live Art Workshop, receiving training from art experts all around the world. In 2019 Burger opened her first solo exhibition of paintings titled, Painted Mantras, at GUS Gallery and facilitated a group collaboration project titled, Take Flight, selected to be part of Infecting the City Live Art Festival. At the moment, Nicolene is completing a practice-based master’s degree in Theatre and Performance at the University of Cape Town.

In 2020, Nicolene created a series of ZOOM performances with Lumkile Mzayiya called, Evoked?. These performances led her to create exclusive performances from her home in 2021 to accommodate the mid-pandemic audience. She also started focusing more on the sustainability of creative practices in the last 3 years and now offers creative coaching sessions to artists of all kinds. By sharing what she has learned from a 10-year practice, Burger hopes to relay more directly the sense of vulnerability with which she makes art and the core belief to her practice: Art is an immensely important and powerful bridge of communication that can offer understanding, healing and connection.

Nicolene writes our blog posts on art history with an emphasis on renowned artists and contemporary art. She also writes in the field of art industry. Her extensive artistic background and her studies in Fine and Studio Arts contribute to her expertise in the field.

Learn more about Nicolene Burger and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Nicolene, Burger, “Gardner Museum Heist – The Story of the Notorious Art Robbery.” Art in Context. November 10, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/gardner-museum-heist/

Burger, N. (2022, 10 November). Gardner Museum Heist – The Story of the Notorious Art Robbery. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/gardner-museum-heist/

Burger, Nicolene. “Gardner Museum Heist – The Story of the Notorious Art Robbery.” Art in Context, November 10, 2022. https://artincontext.org/gardner-museum-heist/.