Louise Bourgeois – Petite Giant of 20th Century Art

Emerging in the 20th century, French American artist Louise Bourgeois’ career spanned over seven decades. She was associated with various art movements like Surrealism and Feminist art but became a member of none. Of her many sculptures and installations, she is best known for her large-scale spiders and cells. Bourgeois continued to produce art and exhibit until she was almost 100 years old.

Table of Contents

The Intimate Art of Louise Bourgeois

| Date of Birth | 25 December 1911 |

| Date of Death | 31 May 2010 |

| Place of Birth | Paris, France |

| Associated Art Movements | Surrealism, Feminist art, Contemporary art |

| Genre / Style | Sculpture, Installation, Printmaking, Drawing, Painting |

| Mediums Used | Textiles, glass, wood, steel, bronze, latex, marble, plaster, plastic |

| Dominant Themes | Childhood, Sexuality, Memory, Motherhood, Gender, Freud, Trauma |

Like other famous artists like Francis Bacon and Edvard Munch, Bourgeois turned her pain into form. As a woman artist, she shed light on female sexuality and the anxieties of motherhood, which was unprecedented.

Louise Bourgeois has inspired feminist artists like the Guerrilla Girls and even collaborated with female British artist Tracey Emin.

Early Life

Louise Bourgeois was born on Christmas Day 1911 in France in the lead-up to the first World War of 1914 which her father participated in. The middle child of three, Bourgeois was much closer to her mother. She was named after her father Louis, who clearly would have preferred a son.

Her parents owned a gallery in Paris, which sold antique tapestries. Her mother, Josephina Lewitz, had come from a long line of tapestry makers and repaired damaged tapestries at the gallery. The Bourgeois children grew up with the smell of yarn in the air and Louise began drawing and sewing to help her mother in tapestry restoration.

Many of the tapestries featured nude figures which made them difficult for her father to sell. Louise was tasked with obscuring the figures’ genitals, sketching patterns of flowers or leaves so that her mother could weave them onto the surface. This experience made her associate her hands with creativity and image-making from an early age.

Sadie

Theirs was far from a happy home. In 1922, when Louise was 11 years old, her father hired a young governess called Sadie Gordon Richmond to teach the Bourgeois children English. As an adolescent, Louise discovered that Sadie had become her father’s mistress. Sadie’s tenure as their English tutor filled Louise’s childhood homes with secrets and deception. Sadie, who was just a few years older than Louise, lived under their roof for about ten years and became very much a part of the family.

Louise’s mother, who had fallen ill before Sadie arrived, seemed to have no choice but to tolerate it and her health worsened after 1922. Louise saw her father’s actions as abandonment and felt betrayed by Sadie, whom she had initially liked. This dynamic played a decisive role in her artistic development.

A Surreal Start

When she was 18, she worked as a guide at the Louvre and, despite her explicit connection to art, she enrolled to study geometry at the Sorbian. Louise had an interest in abstraction, spirals, and repetitive motions but it was the rules of geometry that attracted her. They offered a sense of stability and order that her father had deprived her of.

But in 1932, two years into her studies, Louise’s mother died, at which point she abandoned her mathematics education and focused instead on pursuing art.

Her father was displeased and refused to pay her art school tuition fees. She made an arrangement to attend classes for free in exchange for working as a translator for the English-speaking students, leaning on the training she had received from Sadie.

As a painting student at prestigious academies like the Académie de la Grande-Chaumière, the École des Beaux-Arts, and the École du Louvre, she worked as a studio assistant for the atelier of Fernand Léger, a well-known modern artist who first identified her as a sculptor and opened her eyes to the possibilities of working in three dimensions.

Her first apartment in Paris was on the same street as the Galerie Gradiva, which was run by the leading figure of Surrealism Andre Breton. Breton inspired his fellow surrealists to incorporate Freud’s therapeutic techniques into their artistic practice, by mining their subconscious.

Louise Bourgeois began associating with the Surrealists albeit in an ambivalent way. She found Andre Breton particularly pontifical and said Marcel Duchamp could have been her dad which, of course, was far from complimentary. The Surrealists were all men and only welcomed rich women, which left no room for her.

The Masculine Mystique

Bourgeois’ view of men was complicated, to say the least. Firstly, she felt she had displeased her father before she was even born by not being a boy. His affair with Sadie filled her with jealousy, sadness, and even hatred. She was afraid of men and yet she craved their approval and attention. She once said, “from a sexual point of view, I consider the masculine attributes to be extremely delicate, they are objects that the woman themselves must protect.”

As a young artist, Bourgeois had briefly tried her hand at art dealing to support herself.

This is how she met American art historian Robert Goldwater, who was in Paris for work and looking to buy some prints from her. He reminded Bourgeois of her mother, not her father and she fell in love. The two got married and moved to New York in 1938 just before World War II.

The 1940s were hard for Bourgeois, who struggled to assimilate to American culture. Her alienation worsened when she became a mother to three sons in just four years. She became anxious, depressed, and riddled with doubts about the life she had chosen. She had dark thoughts about her children, her husband, and herself. One of her written accounts mentions an “inability to establish a reasonable and peaceful relationship with Jean-Louis” (one of her sons) and an “inability to reach intimacy with Robert.”

Then in 1952, her father died, launching her into a deep depression. She withdrew from society and even stopped exhibiting for about ten years.

Bourgeois decided to consult a psychoanalyst, doctor Henri Lobenveld, a second-generation Freudian, who was interested in the implications of trauma on art and artists. Bourgeois sometimes saw him four or five times a week and remained in treatment for 33 years until Lobenveld’s death in 1995.

Penis Envy

When she returned to art-making in the 1960s, Lobenveld’s Freudian influence became apparent in Bourgeois’ work. Sigmund Freud’s theories motivated her to cope with her emotional struggles by occupying her hands to invent visual imagery. Though the subject matter of her art was emotion, she did not appreciate her process being described as art therapy but preferred to call it “exorcism”.

After a trip to Italy in the late 1960s, Bourgeois began working with the medium of marble. For centuries artists like Michelangelo and Rodin had been turning this hard stone into human flesh, referring to its sensual qualities.

Bourgeois’ sculpture Sleep 2 (1967) reduced the potency of the phallus to an unthreateningly proportioned flaccid form. Unsatisfied with portraying its “sleeping nature” just physically, the artist re-emphasized it in the title. In this way she neutralized the potential threat of the still thick, large, and somewhat rough-looking protrusion which sat on its pedestal, distanced from the viewer, accentuating its docile demeanor.

The first version of Fillet (1968) was made with layers of latex over plaster. The phallic form of the object was enhanced by the surface’s resemblance to human skin. But the form is unexpectedly complicated by the dual title which in French means “little girl”. Scholars have speculated on Bourgeois’ gender-bending intentions, pointing out that the middle of the work looks like a cloaked female figure and the bottom part is indicative of hips, while the bulbous forms could signify breasts.

Whatever the artist’s intention, it’s clear that something had indeed been exorcised. Bourgeois’ wordplay revealed a relieved sense of play not often spoken about in her work. The phallic form is no longer threatening. In a photograph taken by Robert Mapplethorpe, we see Bourgeois holding Fillet under her arm like a handbag, and her facial expression shows how humor allowed her to deal with difficult or complex things.

Bourgeois’ obsession with the phallic form at this stage in her career evokes the Freudian notion of penis envy, a term which she used in her writing citing a “realization of a desire to urinate standing up”.

But her conflicted relationship with masculinity was tenderized by her true love for men. She stated: “Everything I love has the shape of people around me. The shape of my husband, the shape of my children, so when I wanted to represent something I love, I represented a little penis.”

Women’s Work

After Bourgeois had re-emerged in the 1960s from motherhood and depression, she began interrogating subjects that had not previously been tested in art history. She returned to drawing and in her varied and extensive mother and child works, it becomes unclear whether she identifies as the mother or the baby.

Either way, she explored the fraught relationship between the mother and child. Her images often depicted the good or bad mother.

She tied her female figures to the provision of milk and illustrated the abandoned baby through the notion of spilled or wasted milk. These images are concerned with the anxieties and ambivalence of maternity and the competing roles of woman, wife, and mother.

Her husband Robert Goldwater died in 1973, which marked yet another development in her artistic style. Her works were suddenly thick with themes of desire, lust, and sex. Her beautiful yet repulsive forms became viscerally lumpy using new materials like plaster and plastic. It became about bodily function and body parts with a focus on femininity. By depicting the woman’s experience of desire and dread in works like Knife Woman (1975), she added a new set of terms into the art canon.

Louise developed an underground reputation long before she broke into the mainstream art world. In the late 70s, her work had been embraced by the growing feminist movement in America. She earned an income teaching at places like the Cooper Union, Brooklyn College, and the Pratt Institute, which kept her in touch with a young generation of women artists.

She was already in her 60s at that point, living alone after the death of her husband. She would invite these young artists to her home and though her critiques of their work were harsh, she was cast in an authoritative, maternal role, which she enjoyed.

Seminal Pieces

Louise Bourgeois famously said that she was too small for her emotions. She knew that she was driven by her traumas. She was an intelligent individual but when it came to her feelings, she could be immature. When Louise was hurt or afraid, she became aggressive and destructive. She had a short temper and often lashed out at loved ones. In her own words: “when I do not attack, I do not feel myself alive”.

In a sense, her artworks were attempts to attack, without hurting those around her.

Personages

When she began creating these sculptures in the 1940s, she was homesick for France and felt guilty and anxious about her separation from her family. She felt freer in America but she was also lonely and had difficulty making friends. Bourgeois often worked on their shared rooftop where she became enamored by the skyline of New York.

She appreciated the verticality, solidity, and scientific quality of the architecture and began making anthropomorphized works that reflected the human condition in that they were together, yet apart. She represented each building as a person. One skyscraper was a lonely person, two next to each other were a couple, a third figure suggested jealousy, and if they separated, they symbolized estrangement.

The Personage figures were also inspired by her American family. Her husband Robert Goldwater being the founding director of the Museum of Primitive Art was an expert in African and Symbolist visual culture. This influence is palpable and garnered the sculptures a reputation as totem pole statues, which shared the supposedly primitive African function of spirit holding objects. She even produced a beautifully wonky and slight skyscraper for her son Jean Louis with whom she shared a difficult relationship.

Initially, these were carved from wood, but Bourgeois would later cast them in bronze. The long and lanky vertical figures were often assembled with stacked components and often exceeded the height of the average person. The spindly appearance of the personages offers many interpretive readings. The examples which resemble sewing needles or strung together with beads could be interpreted as references to her textile background.

Some interpretations point out the phallic nature of early Personage, which is obvious from the erect appearance of the vertical forms though the phallic themes were not yet as explicit as they would become in the following decades.

Still, Bourgeois’ description of the Personage pieces as darts implicates them as having a threatening theme.

Destruction of the Father (1974)

While this work was clearly about the complex nature of her relationship her with father, it was made directly after her husband’s death. Perhaps her loss compelled her to come into contact with the twisted nature of her impulse towards the father figure. About Destruction of the Father (1974), Bourgeois wrote: “the children grabbed him, the father and put him on the table and he became the food and they took him apart, dismembered him, ate him up and so he was liquidated the same way he liquidated his children.”

“Destruction of the Father” was a cathartic endeavor for Bourgeois, which may have had links to Freud’s Oedipal complex theory.

Based on the story of Oedipus from ancient mythology, the feminine version of the Oedipal complex is oddly called the negative Oedipal complex in which the little girl subconsciously wishes her mother dead to marry her father. This work encompassed her dark childhood fantasies in which she threw her adulterous father into the dimly lit cave to face his demise. Bourgeois constructs an eerie landscape that sprouts mushroom-like forms made of latex, plaster, and wood.

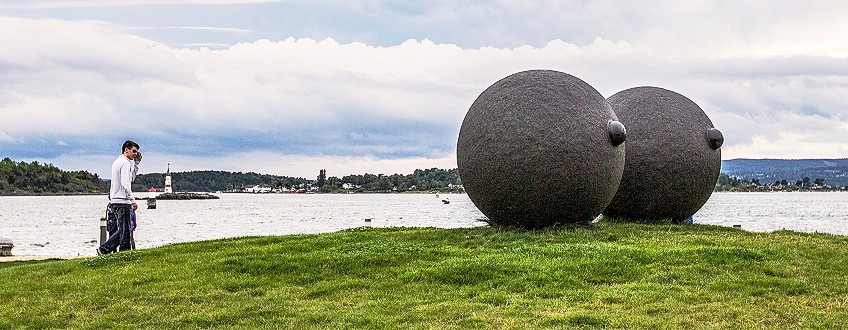

This work was Bourgeois’ first self-enclosed environment or installation. The effect of the illuminated space, its suggestive red lights, and the bulbous shapes arranged in attendance around what seemed to be both a table and a bed, gave the illusion that the stage had been set for a sacrificial ritual.

The Cells

Bourgeois’ expansion into built environments continued with her famous body of work known as The Cell series which she began in the 1970s but was brought to life in the 1990s. At times the structures were elementary enclosures, designed to fit a single person. Dangerous Passage (1997) engulfed the entire gallery space and looked just like prison cells, the series of cage-like rooms made of chain link fence, was the largest Cell structure ever made by Bourgeois.

Inside the space, the viewer encounters a progression of enclosures all filled with items of significance for Bourgeois.

School desks reference her childhood, perhaps Sadie. There are shirt cuffs that belonged to her father, embroidered with the family name, and the work ends in a space where chairs are suspended from the ceiling, another reference to her father who kept antique chairs in the attic of the family home suspended from a ceiling beam. Over a table, a couple is engaged in a sexual act.

The progression of the scenes could be read as a reference to Freud’s stages of psychosexual development. For the Bourgeois, they were also metaphors for the human body in which a cell is a singular entity linked to the whole organism. In Freudian terms, the cells of the body were the hosts of the psyche.

The triumphantly succinct “Cell: The Last Climb” (2008), with its spiral opening up in a rising motion, gives the impression that Bourgeois had worked through some things and was now ready to move forward. It was made two years before her passing.

Spiders

Bourgeois’ work shifted in the last 15 years of her career and she stopped making any reference to her father. From here on, her work became about the mother. Despite Bourgeois’ childhood connection with textiles, her work did not engage fabric until the 1990s when she was already in her 80s. Her interest in the softness and the mutability of fabric manifested in obvious ways, as in her Ode to Forgetting (2004), in which she constructed collages out of pieces of her old clothing, and in more subtle ways.

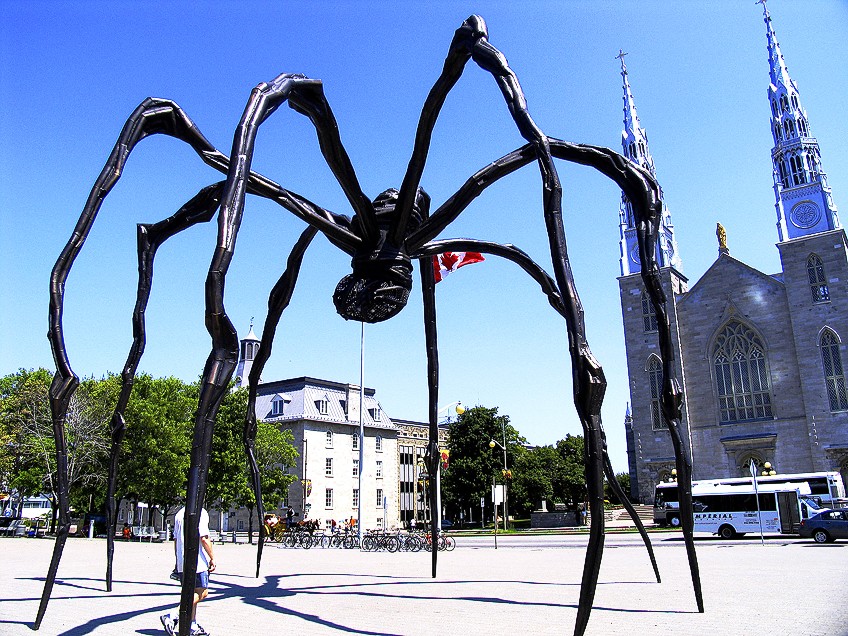

Weaving was her mother’s profession and a fitting metaphor for her healing from dysfunctional family ties as well as the creative process. Bourgeois used this metaphor in the colossal structures she called “Spiders”.

The first spider dates back to 1947 in the form of a drawing. Because tapestries were so central in her childhood home, she came to associate weaving with maternal care. While many people are afraid of spiders, Bourgeois represented them as the weavers, makers, and protectors who build their architecture out of their bodies. Louise used the spiders as odes to her mother. While for her the huge structures were safe spaces, she played on the ambivalence between safety and danger.

In the year 2000, when the Tate Modern first opened, they exhibited Bourgeois, who was still relatively unknown. Her huge spider sculptures, which she called “Maman” (1999) or “Mother”, made an even bigger impact and secured her a place in public memory as one of the most influential contemporary artists.

The Final Fringe

In 1982, after 42 years of work, Louise Bourgeois was awarded the first large-scale sculpture retrospective by a woman artist at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She dazzled the contemporary art world with her prolific body of work. Her career had reached its conclusion.

She became agoraphobic and never left her house for the last 20 years of her life.

She was arthritic and an insomniac but even in her frailty, her hands were never still and she sat at her desk in her bedroom on the ground floor of her New York City home, in which she had lived for nearly 50 years and continued making art until she died at 98.

Recommended Reading

Here are some books which give more in-depth information on Louise Bourgeois’ biography and career. These all provide a dynamic insight into different aspects of her artworks. We’ve given you a brief summary of some of the most popular books on Amazon in no particular order.

Louise Bourgeois & Pablo Picasso: Anatomies of Desire (2019) by Marie-Laure Bernadac

This is a thought-provoking juxtaposition of the work of Louise Bourgeois and Pablo Picasso presented as an accompaniment to the 2019 Hauser & Wirth Zürich exhibition of art objects from both artists. With various texts written by leading art professionals, it is a beautiful book based on both artists’ explorations of sexuality and intimacy.

- Beautifully designed book with cloth boards and title stamping

- Double portrait of the works of Louise Bourgeois and Pablo Picasso

- Thought-provoking discourse on artists' formal and iconographic links

Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait (2017) by Deborah Wye

This book was published alongside Louise Bourgeois’ major 2017 exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art in New York. The chronological survey and bibliography focus on Bourgeois’ print practice within the context of her overall career. The lesser-known prints which number over a thousand share the themes of her broader work. The book includes interviews with Bourgeois’ long-time assistant Jerry Gorovoy.

Louise Bourgeois: The Fabric Works (2011) by Germano Celant

This book was made as a collaboration with the editor Germano Celant and Louise Bourgeois in her New York studio. As the title suggests the book cataloged the artist’s fabric works which came before the larger public sculptures she is better known for. It follows the origins and developments of the artist’s interest and use of fabric.

- Edited in collaboration with the artist and her New York studio

- Images are collected here in their entirety for the first time

- Constitutes the closest thing yet to a general catalog

In her wake, Louise Bourgeois left behind a treasure trove of work, which is a central part of the canon of women artists. While she laid herself bare in these works Louise Bourgeois did not simply wish to be subjected to uninvited curiosity. The narrative she offered the world to some extent was mythical. Bourgeois’ body of work spoke on her behalf and it proclaimed itself as the undone hem between neurosis and confession.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Is Jerry Gorovoy?

Jerry Gorovoy is the former assistant and close companion of Louise Bourgeois. Ever since the early 1980s, Gorovoy helped Louise operate her studio and organize her exhibitions. He is still in charge of her artistic affairs to this day.

Was Louise Bourgeois Abused?

There is no evidence that Bourgeois was physically violated but in her 1982 Artforum Magazine essay, Child Abuse, which featured several photographs of the artist and her family during her childhood, she intimated her deep feelings of abandonment, betrayal, and internal conflict with regard to her father.

Was Louise Bourgeois a Feminist?

Louise Bourgeois was considered a feminist because her work focused on women’s issues and had a similar aesthetic to many feminist artists of the time, but she never officially accepted the term. In fact, she has often denied it.

Heidi Sincuba was the Head of Painting at Rhodes University from 2017 to 2020 and part of the first Artist Run Practice and Theory course at Konstfack in Stockholm, 2021. They completed their BFA at Artez Arnhem in the Netherlands, MFA at Goldsmiths University of London, and are currently a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Cape Town.

Heidi Sincuba’s own practice explores fugitivity through painting, drawing, text, textiles, performance, and installation. This praxis is founded on a conceptual intersection of biomythographic experimentation, existential automatism, and African ancestral knowledge systems. These methodologies of multiplicity result in a fluid and speculative aesthetic, continually manifesting and metamorphosing its material conditions.

Learn more about the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Thembeka Heidi, Sincuba, “Louise Bourgeois – Petite Giant of 20th Century Art.” Art in Context. April 6, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/louise-bourgeois/

Sincuba, T. (2022, 6 April). Louise Bourgeois – Petite Giant of 20th Century Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/louise-bourgeois/

Sincuba, Thembeka Heidi. “Louise Bourgeois – Petite Giant of 20th Century Art.” Art in Context, April 6, 2022. https://artincontext.org/louise-bourgeois/.