Zeus Statue Olympia – Discover Greek Art and the Iconic Statue of Zeus

Counted among the Seven Wonders of the World, pilgrims from all across the Mediterranean came to worship the statue of Zeus at Olympia, which inspired innumerable imitations and determined the standard portrayal of Zeus in Greek art. The Olympia statue of Zeus is a chryselephantine sculpture, which signifies that it was crafted out of gold and ivory. History has left no remains of the Zeus sculpture; it was destroyed, and there are only a few reproductions from the period it existed.

Table of Contents

The Zeus Statue at Olympia

| Sculptor | Phidias |

| Date | c. 457 BCE |

| Dimensions | 64 m x 27 m |

| Current Location | Destroyed |

The Olympia statue of Zeus, constructed in the 430s BCE under the direction of great Phidias, the Greek sculptor, was even larger than Athena’s statue in the Parthenon. Following its move to Constantinople, the statue of Zeus at Olympia was lost in later Roman times, but it enthralled the world of the ancient era for 1,000 years and was a must-see site for anybody attending the ancient Olympic Games.

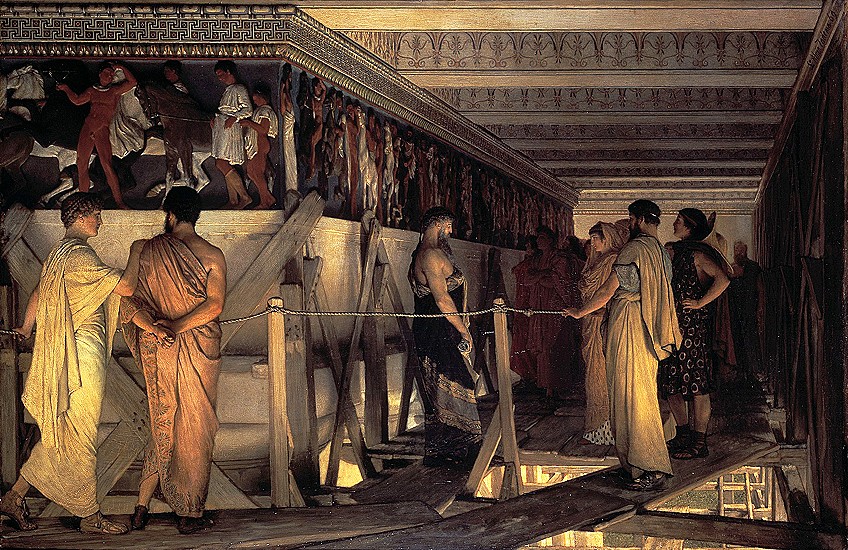

Phidias worked in Olympia in a particularly specialized studio, where archaeologists discovered some relics from that historical period, revealing to us the techniques utilized in this ancient Greek artform.

The Reason the Zeus Sculpture Was Built

From the 7th century BC, the city of Olympia was a significant cultural hub of ancient Greece. It is the site of the ancient Olympic Games, a world-renowned sporting tournament whose contemporary counterparts are held every four years. According to Greek mythology, the city was put under the guardianship of Zeus, the Prince of the Gods. It boasted a temple that had been extensively reconstructed in the 5th century. This massive new temple had to fit a massive statue.

As a result, the erection of the Zeus monument was based solely on religious beliefs. Simply put, it was an issue of commemorating the city’s patron at a moment when Olympia was gaining prominence throughout ancient Greece.

The great sculptor Phidias, who had previously overseen the creation of Athens’ Parthenon and its massive sculpture of the region’s patron deity Athena, was commissioned to create an equally gigantic Zeus statue at Olympia. It was here that every four years the Pan-Hellenic Olympic Games were held.

The city-state of Elis ruled over Olympia at the time, and the hallowed location drew thousands of visitors, pilgrims, and sports enthusiasts from all across the Mediterranean. The new cult figure and temple to hold it would be excellent additions to Olympia at a period when rival games were still conducted at other locations including Nemea, Delphi, and Isthmia near Corinth.

Furthermore, a great commitment to Zeus, the creator of the Olympian gods and the ultimate figure of ancient Greek mythology, would be beneficial to the Eleans’ spiritual and intellectual well-being, as well as the psychological and physical well-being of all of classical Antiquity. Phidias was the ideal candidate for a difficult job that would need hundreds of workers and several years of labor.

The master sculptor relocated to Olympia, and digs in the 20th century CE uncovered his studio, which included a basic red-figure wine jug etched with the words “I belong to Phidias.” The workshop also had ivory tools, a tiny hammer for dealing with gold, and molds for components of a big female statue.

Description of the Zeus Statue at Olympia

A temple was regarded as the home place of a god in ancient Greek religion, as its name naos (‘residence’) implies. As a result, the god statue within was considerably more significant than the temple itself. The statue was usually positioned in the center of the structure so that when the doors were opened, it could see the sacrifices and rites being done in that god’s honor just outside. Whether the worshippers truly thought that the deity possessed the statue is debatable, but prayers and ceremonial movements were clearly directed towards it.

It is also worth noting that one of the typical titles for a sculpture in Greek was “zon”, or “alive thing,” indicating the sculptor’s attempt to capture living stuff in unfeeling metal or marble.

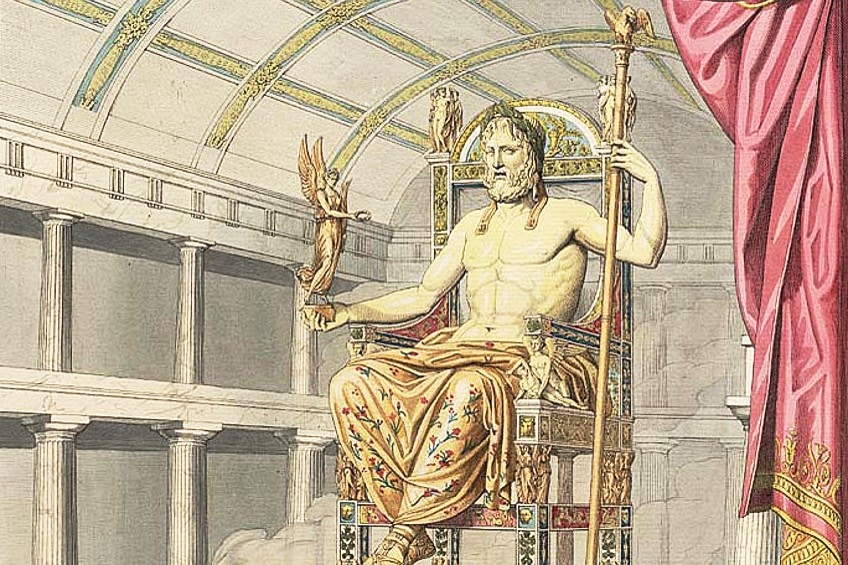

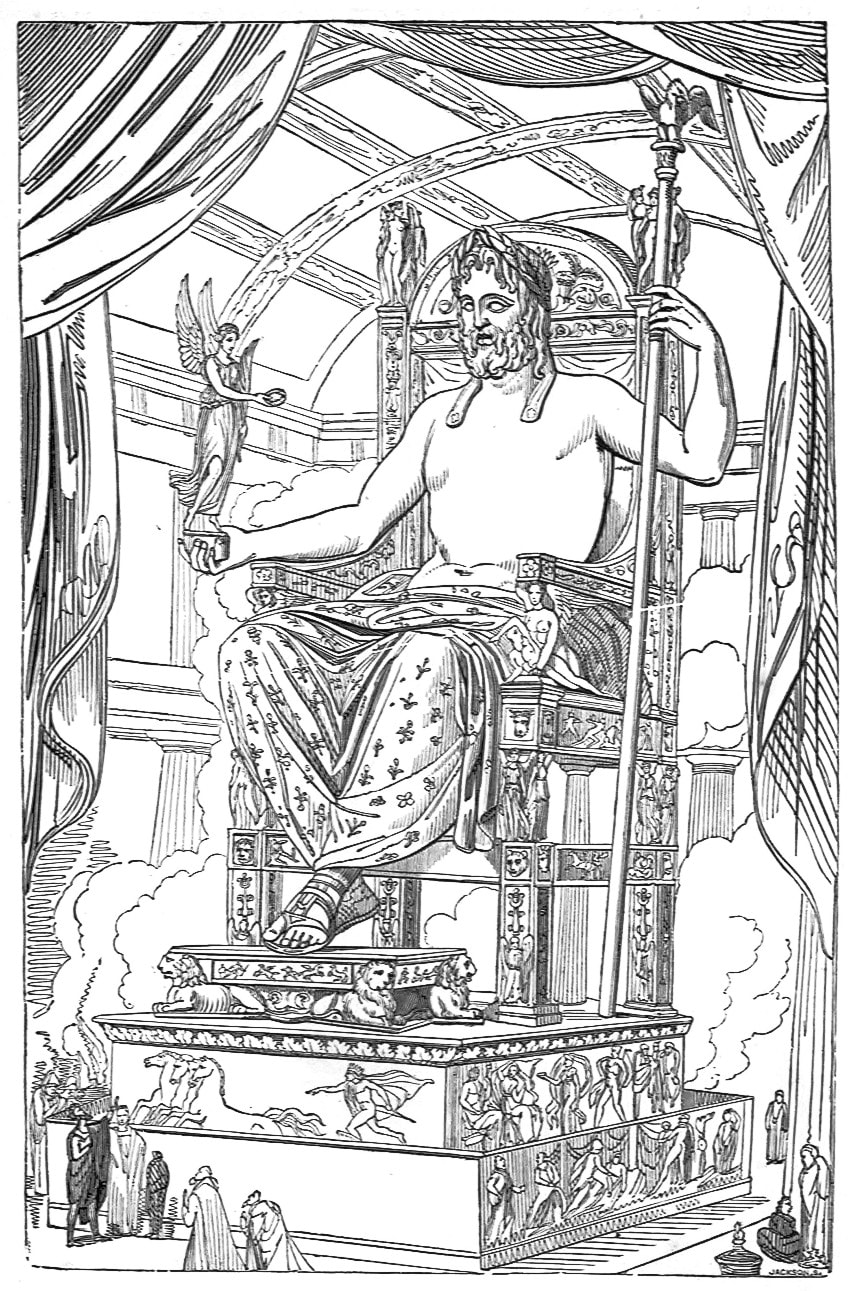

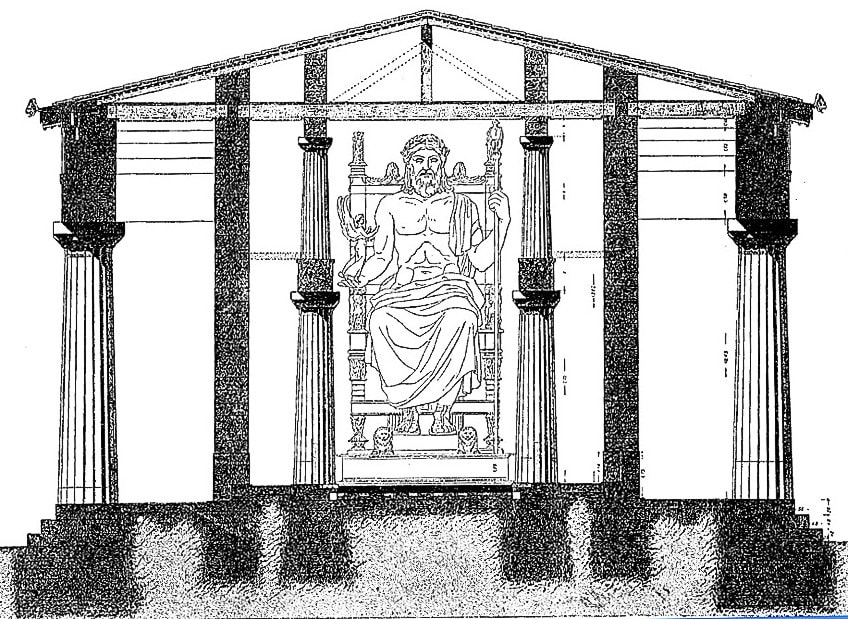

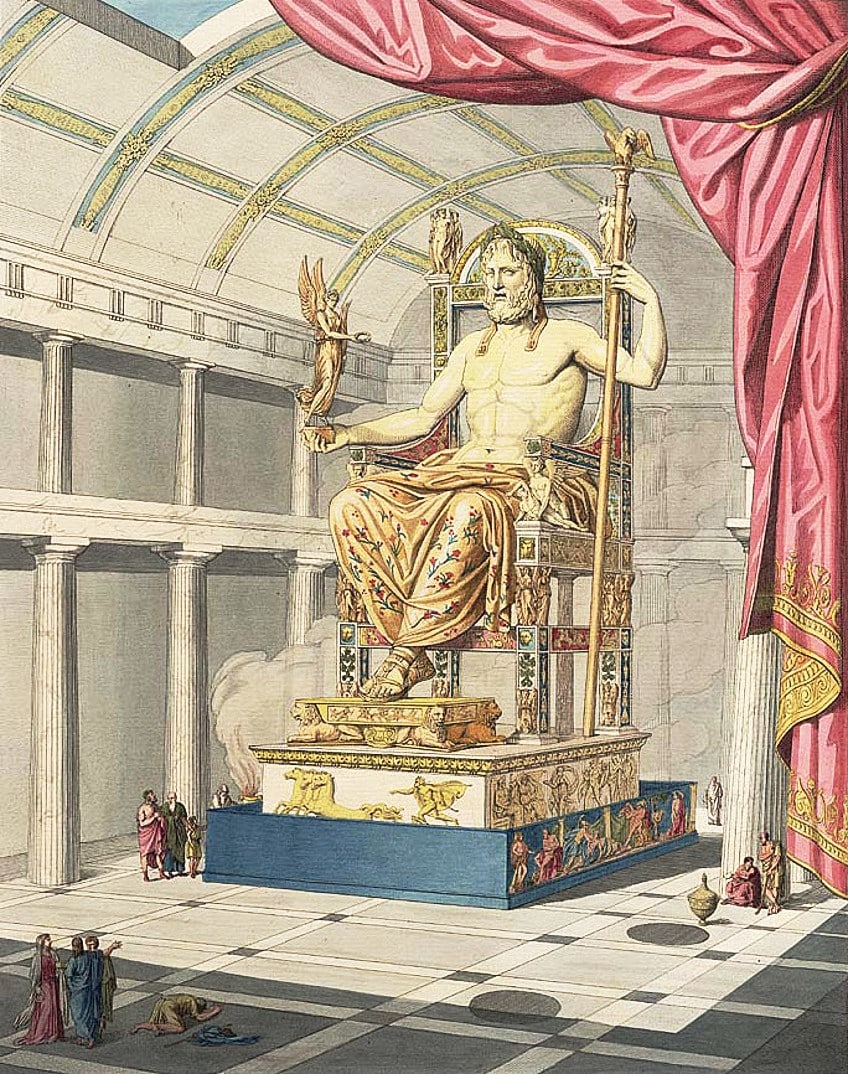

Phidias’ idea was of a statue so large and gleaming in gold that it would be nothing short of an awe-inspiring discovery to the beholder, bridging the gap between humans and the divine. The colossal Zeus sculpture stood over 12 meters tall and depicted the god reclining on a throne. It was even larger than the Athena Parthenos in Athens.

The statue of Zeus at Olympia, like Athena’s, was chryselephantine, which means that it was made of ivory and gold over a wooden core, with the god’s skin (head, torso, limbs, and legs) in ivory and his hair, garments, and rod in dazzling gold added in hammered sheets. Silver, copper, glass (for the ornamental lilies of the god’s clothing), enamel, ebony, paint, and gems were used to highlight fine features.

The clay molds unearthed in Phidias’ studio for a similar sculpture show that it was originally constructed there in sections – the workshop is precisely the same size as the temple’s inner cella – and then reconstructed at its eventual destination. The wooden center could not have been entirely molded, else the molds for shaping the outside gold parts would have been unneeded.

The most detailed account of the Greek artwork from ancient sources may be found in Pausanias’ Description of Greece, written in the second century CE by the Greek explorer Pausanias: The deity sits on a throne composed of ivory and gold. Placed upon his head is a garland resembling olive branches. He holds a Victory in his right hand, which, like the sculpture, is made of gold and ivory; she sports a ribbon and a wreath on her head. The god’s left-hand holds a scepter adorned with various metals, and the bird perched atop the scepter is an eagle.

Other noticeable traits are that the god’s footwear is also made of gold, and so are his robes. Embroidered images of animals and lily blossoms adorn the robe. His majestic throne is encrusted with gold and gems, not to forget ivory and ebony. Zeus’ throne, crafted of ebony, ivory, and gold and flecked with glass and precious stones, was adorned with carving portraying a broad range of Greek mythology figures, many of whom were deemed Zeus’ offspring.

There are the Graces, the Seasons, a variety of Nikes, Amazons, sphinxes, and Niobe’s offspring.

The screens between the thrones’ legs were painted by Phidias’ brother Panaenus and showed Hercules’ Labors, Hippodamia with Sterope, and other Greek themes. The deity placed his feet on a footstool depicting a war scenario between Theseus and the Amazons. The Zeus statue at Olympia, throne, and stool was all set on a black Eleusinian marble pedestal. The base was adorned with images from Aphrodite’s birth. Finally, Phidias signed the base, writing, “Phidias, son of Charmides, an Athenian, created me.”

There are the Graces, the Seasons, a variety of Nikes, Amazons, sphinxes, and Niobe’s offspring.

How the Zeus Statue at Olympia Was Created

Of course, we don’t know how Phidias labored when he erected this statue. Furthermore, scholars are unsure of the precise periods he spent on Olympus, but we do know the dates of labor in Athens for the completion of the statue commissioned by Pericles: 447 to 438, or nine years.

As a result, it appears plausible that the work at Olympia lasted a comparable amount of time. What we can be certain of is that he never worked alone; he was always a team leader who oversaw the artisans of various professions.

This was supported by archaeological studies conducted at his workshop, where we discovered artifacts from many employees. Phidias had the designs used as a project at this studio near the temple. He had cabinetmakers construct the different parts of the monument, which he assembled directly into the temple, based on these drawings. Then he sculpted small slices of ivory that he sculpted and whose purpose was to overlay the skin on the figure. If the Athena statue just featured the face of discovery, Zeus’ statue had the entire body, making the effort of a completely different magnitude.

So, how do you generate a huge surface with ivory, which is a somewhat stiff substance with narrow leaves? It is conceivable to unfurl leaves that are larger than a slice created in its core by cutting them correctly. The leaves had to be loosened so that they lost their stiffness, which was accomplished by an unknown procedure. It is known that after ivory has been relaxed, it may be physically manipulated, but the procedures of relaxing differ from civilization to civilization and time to era, and we do not know what was done in Olympia during the Antiquity.

Finally, after the ivory plates were finished, they were presumably glued together and buffed to make them sparkle and hide the seams. The clothing was composed of silver or gold in the shape of thin leaves that were shaped to fit the curves of the wood.

The quality of the work appears to have been so high that the seams between the panels could not be seen, giving the statue the appearance of being made of ivory and gold.

The throne was painted rather than coated in ivory or gold. Despite his mastery in painting, Phidias had this task be done by a person in the family, Panaenos, who decided to recreate scenes from mythology. These moments appear to have been a huge success. Nevertheless, we understand that glass was utilized on the monument, although experts disagree on its function. Glass was a costly material that originated from the eastern Mediterranean at the time.

About the Temple

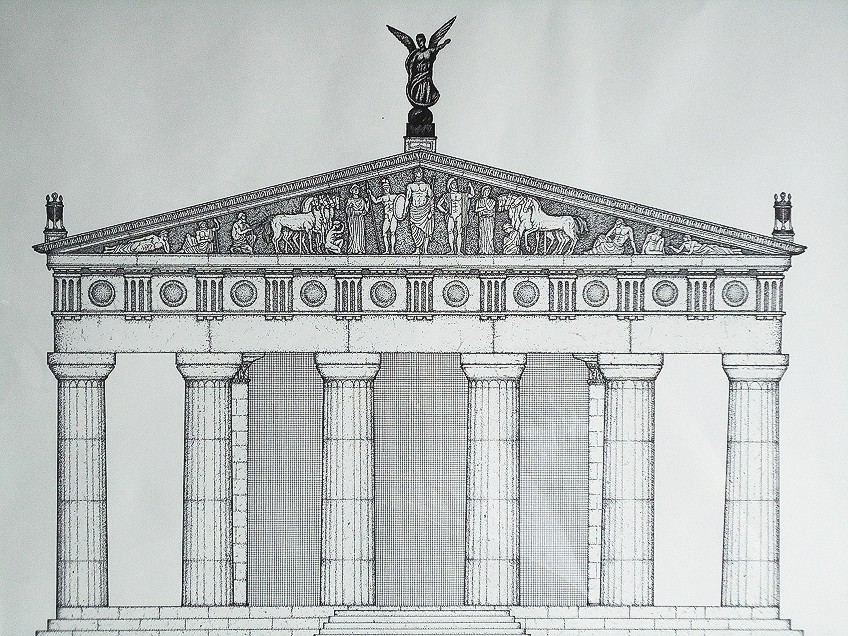

This temple stood out from the others because it was the longest, widest, and tallest of them all. The temple of Zeus, as we know it now, was not the first structure built in this location. Olympia’s history dates back to the 8th century BC when the very first Olympic Games were held in 776 BC. Initially, a temple was constructed to the south of Mount Kronos in the 7th century, serving as a cult hub for the site.

It was built in the Doric style, but its timber columns were rebuilt with stone columns later on. It should be noted that researchers discovered the head of a statue of Hera, Zeus’ wife and the deity of marriage, in this antique temple.

The Eleans won a significant victory over Pisa in the 5th century Bc. To commemorate their victory, they chose to construct a new temple instead of using the old one; it is with this temple that the Zeus sculpture is associated. Elons Libon created it in a similar Doric design as the old one, but with modern components including stucco-coated limestone.

Location of the Temple

Olympia was an important city in Antiquity; it had existed from the protohistoric period and had only been improved until the collapse of the Roman Empire. It was in the west of the Peloponnese, near the shoreline. It was, however, not a seaside town; it was located east of the Kladéos River, in the lush valley of Alpheus. The infrastructure for the Olympic Games was built at Olympia. So the city had a stadium, a theater, and several temples, the most significant of which was of course devoted to Zeus.

It was built in the Doric style, but its timber columns were rebuilt with stone columns later on. It should be noted that researchers discovered the head of a statue of Hera, Zeus’ wife and the deity of marriage, in this antique temple.

The Eleans won a significant victory over Pisa in the 5th century Bc. To commemorate their victory, they chose to construct a new temple instead of using the old one; it is with this temple that the Zeus sculpture is associated. Elons Libon created it in a similar Doric design as the old one, but with modern components including stucco-coated limestone.

By choosing limestone rather than marble, all supply and transportation issues were avoided, and the hardness of the stone is great for strength but not for cutting in regular blocks or carving. The roof cover, on the other hand, was nicely marbled. The temple was finished in 457 BCE. It was used for devotion until 397 A when the Roman Emperor Theodosius issued a decree prohibiting polytheistic cults and the Games. It was entirely ruined in the 6th century AD due to the turmoil of an earthquake.

The temple was forgotten and covered by centuries of silt deposits. Richard Chandler, who would excavate for six years, will find the location in the 19th century. From 1936 until 1966, the site would be explored once again.

Description of the Zeus Sculpture Temple

The temple of Zeus was traditional in architecture according to ancient Greek standards. It was rectangular and completely ringed by a series of 10m high columns. It featured an east entrance and a two-sloped roof that rose to 22m in height, producing a gable on the front and rear facades.

The two pediments were lavishly ornamented. The one in front featured Zeus in the middle, surrounded by depictions of the chariot races, in which Pelops and Enenos competed for Hippodamia’s hand, according to legend. The one in the rear depicts the Centaurs’ struggle with the Lapiths. Apollo is seated in the center of the western pediment.

When the sun rose, it penetrated the vestibule, the chamber used as an entry, and it even reached the Naos depending on the seasons. has two rows of columns to support the wooden frame.

The temple had two floors on the inside, with a spiral staircase leading to the upper floor via the wooden galleries. The opisthodome, a chamber behind the sanctuary that housed the offerings, was located at the back of the Naos. This artwork, which was closed to the public, was beautifully embellished with scenarios involving Herakles and is currently on display at the Louvre in Paris. The temple’s floor was built of massive slabs of limestone overlaid with marble slabs.

The Seven Wonders

Some of the ancient world’s monuments wowed people from all over with their beauty, creative and architectural ambition, and sheer magnitude, earning them a distinction as must-see attractions for the historical traveler and pilgrim. When authors such as Callimachus of Cyrene, Herodotus, and Antipater of Sidon, and prepared shortlists of the most amazing sites of the ancient world, seven such monuments constituted the first ‘bucket list.’

The Zeus statue at Olympia was added to the existing list in the 2nd century BCE, but it was already well-known by that time.

The statue was emulated in sculpture and depicted in vase works of art, engraved gemstones, and coinage dating back to the 4th century BCE, most notably on the counter side of Alexander the Great’s silver tetradrachms and Elis’ coins. In the 2nd century, Hadrian, the Roman emperor, continued to use the same motif on his coins. Aside from these surviving depictions, there are marble reproductions of Niobe’s children from the statue’s throne.

The Olympia statue of Zeus, in turn, drew visitors from all across the known globe. Individuals and city-states contributed money, excellent sculptures, bronze pots, helmets, shields, and weaponry to Zeus, culminating in Olympia becoming a living symbol of Greek art and culture. Many towns also constructed treasuries, which were tiny but spectacular structures that housed their donations and raised the city’s prominence.

Theodosius I, a Christian, decreed the abolition of all cult practices, including the Olympic Games, and the final Olympics were held in 393 CE, after a run of 293 games spanning more than a millennium. After this, the site and temple went into ruin until they were desecrated about 426 CE as a result of Theodosius II’s proclamation against pagan temples, and then totally destroyed by earthquakes in 522 and 551 CE. The ruins were gradually buried in silt carried by the River Alpheus as its route shifted over time.

The statue, however, would not have the same destiny as the temple, since the two were fated to be divided and never united. The statue has been refurbished multiple times, with fractures in the ivory mended and maybe supporting columns inserted beneath the seat. The Roman emperor Caligula dared to try to remove the statue and bring it to Rome, but the project was abandoned after the enormous Zeus inexplicably unleashed a shout of laughter and the structure of the workmen fell, according to the Roman historian Suetonius.

The next humiliation was having its gold components stolen by Roman Emperor Constantine I. Finally, in 395 CE, the statue of Zeus was relocated to Constantinople, where the Zeus sculpture and the temple were destroyed by an earthquake in the 6th century CE. We also have a separate article about the most famous greek sculptures.

According to the historians Zonaras and Kedron’s books, the sculpture was destroyed by fire in 475 CE. Whatever the actual circumstances of its demise, the surviving accounts by ancient writers and tantalizing representations in other old artworks and on coins are all that remain of one of the ancient world’s wonders, the only one that was ever sincerely respected.

The Zeus statue at Olympia was one of two wonders by Greek sculptor Phidias, and it was installed in the massive Temple in western Greece. The almost 12-meter-high statue, plated in gold and ivory, depicted the god seated on an ornate cedarwood throne adorned with ebony, ivory, gold, and valuable stones. The Zeus sculpture, which took eight years to build, was praised for expressing heavenly grandeur and kindness.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Symbols of the Zeus Statue at Olympia?

Unlike previous Zeus depictions, Phidias opted to create a tranquil Zeus with restrained might. Previously, he was frequently depicted in rage, gripping the flashes in his hand. The artist’s goal was to depict a powerful yet peaceful God who is confident in his victory. This is why certain symbols are present: the triumph grasped in his right hand, the crown of the olive branch, a sign of strength.

What Happened to the Site of the Olympia Statue of Zeus?

The location of Olympia is rich in archaeological remains, but because the statue of Zeus was transported before vanishing, it is difficult to discover information on what was there. However, excavations beyond the sanctuary allowed for the upgrading of Phidias’ studio in 1958. There are distinctive carving tools. It also had relics of glass-making activities, as well as ivory, semi-precision stones, gold, bronze, ebony, amber fragments, plaster, and a figure that reads Phidias’s name.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Zeus Statue Olympia – Discover Greek Art and the Iconic Statue of Zeus.” Art in Context. May 2, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/zeus-statue-olympia/

Meyer, I. (2022, 2 May). Zeus Statue Olympia – Discover Greek Art and the Iconic Statue of Zeus. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/zeus-statue-olympia/

Meyer, Isabella. “Zeus Statue Olympia – Discover Greek Art and the Iconic Statue of Zeus.” Art in Context, May 2, 2022. https://artincontext.org/zeus-statue-olympia/.