Rococo Art – Looking at the Luxurious and Light-Hearted Rococo Period

The Rococo style of decorative art, architecture, interior design, sculpture, and painting originated in early 18th century Paris. This exuberant and elegant movement spread throughout France and other European countries like Austria and Germany. The Rococo style is luxurious, extravagant, and light-hearted.

Table of Contents

- 1 A Brief Introduction to the Rococo Style

- 2 The History of the Rococo Style

- 3 The Art and Design of the Rococo Period

- 4 The Gradual Decline of the Rococo Style

- 5 Famous Rococo Artists

A Brief Introduction to the Rococo Style

In terms of a Rococo definition, if there was ever an aristocratic French art style, Rococo is it. Rococo designs were incredibly theatrical and ornamental, designed to impress and communicate wealth. Characterized by lightness, curving forms, asymmetrical values, nature-inspired motifs, and playful themes, the Rococo style is truly unique.

The style of the Rococo period has a strong sense of whimsy. Compared to the Baroque style that preceded it, the Rococo style had a much lighter color palette. Lightness and elegance permeate Rococo design with pastel colors, a lot of gold, and ivory white. Many Rococo interior designers used mirrors to create a sense of lightness and spaciousness.

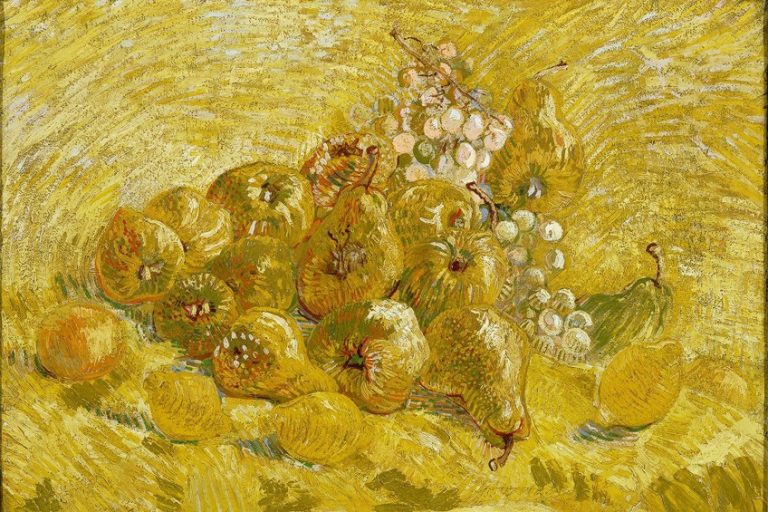

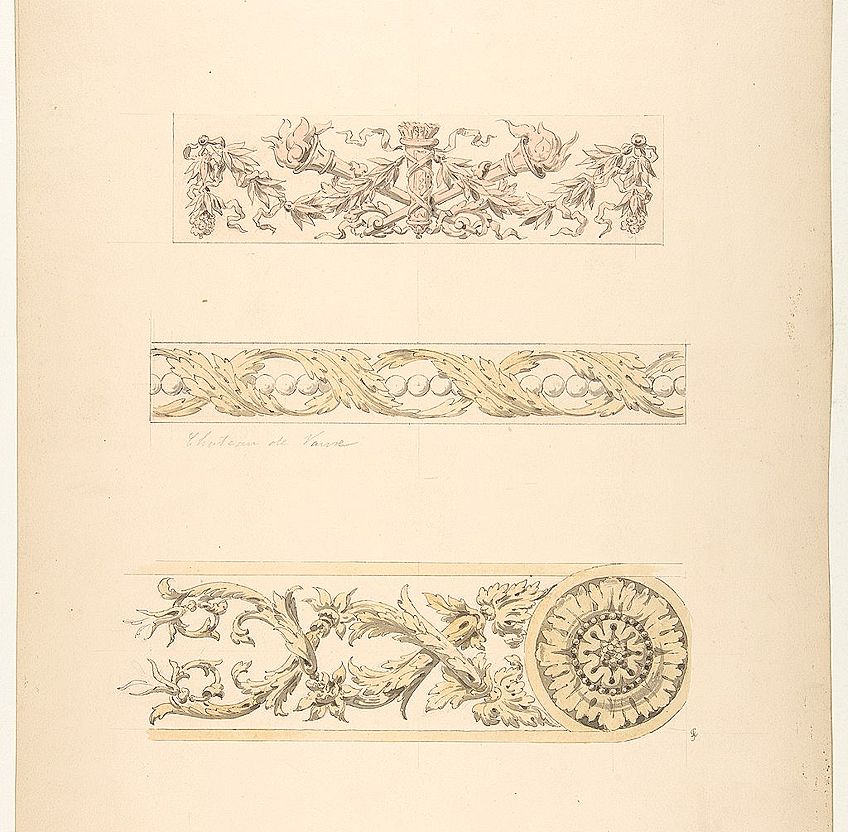

Curving forms were a prominent feature of Rococo design, with swirling scrolls and curvy furniture. Counter-curves and undulations mirrored natural forms, like plants and seashells. Curvacious designs incorporated serpentine lines or sinuous lines that curved in different directions, much like plant vines.

One of the distinguishing elements of the Rococo period is the lack of precise balance in ornamental features. The asymmetry is both within the decoration and within a piece of furniture or architecture as a whole. Furniture and architectural designs often incorporated asymmetrical C-shaped volutes. Asymmetrical values also included the representation of seashells and other nature-inspired shapes. Pieces of Rococo furniture, like cabinets and couches, often had unbalanced decorative elements. Despite the lack of balance in the decoration, the overall sense of balance remains.

A particularly prominent decorative motif used throughout Rococo painting, sculpture, and interior design is nature-inspired. Many of the curved shapes were based on organic shapes like waves, seashells, and other sea-themed motifs. Leaf motifs were also common, with curling vine leaves like stylized acanthus fronds. Although organic in inspiration, these shapes were often exaggerated and gilded.

Playful and lighthearted themes are prominent features of Rococo painting and sculpture. Often, Rococo paintings were based around themes of love, playfulness, and nature. Classical myths were also popular themes among Rococo artists. The popular Rococo themes are another example of how Rococo design rejected the traditions of the Baroque style.

Origins of the Term Rococo

The Rococo definition was first used humorously as a variation of the French word rocaille, a method of decorating grottos and fountains with seashells, pebbles, and cement. Towards the end of the 17th century, people began to use this term to describe a decorative motif that emerged in the late Louis XIV style. This ornamental motif featured a seashell intertwined with the leaves of the acanthus plant.

The first time the term rocaille was used to designate a particular style was in 1736 by jeweler and designer Jean Mondon. Mondon published a catalog of designs for furniture and other decorative ornaments in the rocaille style. These designs for furniture, decorative doorways, and wall panels featured curved shells combined with twisting vines or palm leaves.

In 1825, almost a century later, the term Rococo was printed for the first time. In this context, the Rococo term described the old-fashioned style of the previous century. The term was used throughout the 19th century to describe architecture, music, sculpture, and design that was overly ornamental. Since then, art historians have accepted the Rococo term as the style of 18th-century European art.

Despite the debate surrounding the historical significance of the Rococo style, it is acknowledged as a distinct style of European design.

The History of the Rococo Style

The Rococo style began with interior design and furniture. As a reaction to the strict rigidity of the Baroque era, Rococo design was excessively ornamental. Sometimes art historians refer to the Rococo period as Late Baroque, which began in France as a reaction to the formal style of Louis XIV. When the reign of Louis XIV ended, the aristocratic and wealthy returned to Paris. There, they began to decorate their houses in the Rococo style. Interior designers, engravers, and painters, including Juste-Aurele Meissonier, Nicolas Pineau, Pierre Le Pautre, and Jean Berain, developed a more intimate decoration style for the houses of nobles.

French Rococo

Rococo flourished in France between 1723 and 1759. French Rococo design was most prominent in salons. The salon was a new style of room that was designed to entertain and impress guests. At the Parisian Hotel de Soubise, the Princess salon is a perfect example of Rococo salons.

Exceptional artistry was a defining factor of the French Rococo style, particularly in the frames of paintings and mirrors. These designs often featured intertwined plant forms sculpted in plaster and gilded. These sinuous curves and nature-inspired designs were also popular in furniture design. Leading French furnishers like Charles Cressent and Meissonier were proponents of the Rococo style.

The Rococo style dominated French art and design until the middle of the 18th century, when the discoveries of Roman antiquities steered French architecture towards neo-classical designs.

Italian Rococo

The Rococo style was particularly exuberant in Italy. Venice was the epicenter of Italian Rococo. Italian Rococo designs like the Venetian commodes used the same ornamental decoration and curving lines as the French rocaille, but with a little extra. Many Venetian pieces were painted with flowers, landscapes, or scenes from famous painters. Chinoiserie, or the European imitation of Chinese and other East Asian artistic traditions, was also popular in Italian Rococo.

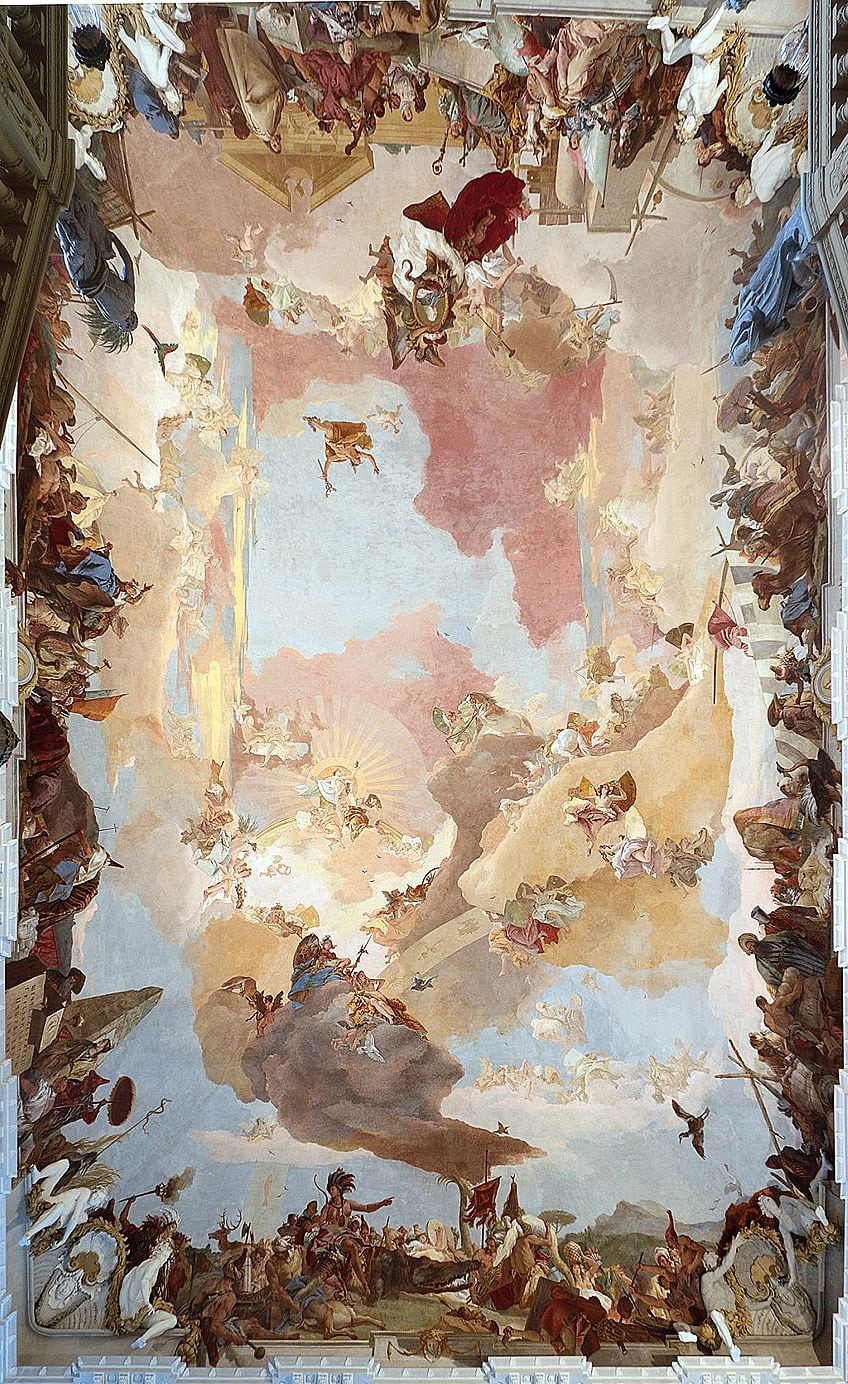

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo was a notable decorative painter from the Italian Rococo period. Tiepolo painted ceilings and murals of palazzos and churches. During the 1750s, Tiepolo traveled to Germany with his son, and they decorated the Wurzburg Residence ceilings. Another famed Italian Rococo painter was Giovanni Battista Crosato. Crosato is best known for the quadrature style painting of the Ca Rezzonico ballroom ceiling.

Venetian glassware was a significant part of the Italian Rococo period. It was during this time that colored and often engraved Murano glass flourished. Glassworks like mirrors with ornate frames and multicolored chandeliers were exported throughout Europe.

Southern German Rococo

It was in Southern Germany and Austria that the Rococo style reached its peak. The published works of French architects and designers introduced the Rococo style to Germany, and it went on to dominate German art and design between the 1730s and the 1770s. While German designers and architects found inspiration in French architects like Germain Boffrand and interior designers like Giles-Marie Oppenordt, German Rococo architecture and design rose to new heights.

The Rococo style of architecture was adopted by German architects who loaded it with even more ornate decoration and made it far more asymmetric. The Rococo decorative style still dominates German churches today. Architects built curves and counter-curves out of molding, creating patterns that twisted and turned and walls and ceilings without right angles. A particularly popular motif was stucco foliage that appeared to creep up the walls and across the ceiling. This ornate decoration was often silvered or gilded, creating a stunning contrast with the pale pastel or white walls.

The first building to be constructed in the Rococo style was the Amalienburg pavilion in Munich. Belgian-born designer and architect Francois de Cuvilies was responsible for designing this building and found inspiration in the French Marly and Trianon pavilions. The Amalienburg pavilion was initially built as a hunting lodge and featured a rooftop platform for shooting pheasants. The interior featured a Hall of Mirrors created by Johann Baptiste Zimmermann. The extravagance of this building was far beyond the architecture of French Rococo.

Another exceptional example of German Rococo architecture is the Wurzburg Residence. This impressive palace had a more Baroque exterior, but the interior reflected the light Rococo style. The residence was designed in consultation with French artists Robert de Cotte and Germain Boffrand and Tiepolo, the Italian Rococo painter, who created a mural above the three-level stairway. The stairway was a central feature of this residence, as was the stairway at the Augustusburg Palace. In the Palace, the grand stairway transported visitors upwards through a vision of sculpture, paintings, decoration, and ironwork.

Although the Rococo style was a secular style at its inception, the German period saw many Rococo-style churches. Throughout the 1740s and 1750s, Rococo architects designed several pilgrimage churches throughout Bavaria. The interiors of these churches have a distinctly Rococo style. Notable examples are Dominikus Zimmermann’s Wierskirche, which had a simple exterior with few ornaments and simple colors. Upon entering the church, however, you are greeted with an oval-shaped deambulatory that floods the church with light. Blue and pink stucco columns in the choir contrast the white walls, and plaster angels surround the dome ceiling.

British Rococo

Although the influence of Rococo was not felt as strongly in Britain as it was elsewhere in Europe, British silks, porcelain, and silverwork did take some inspiration from Rococo. The theoretical foundation for Rococo beauty was laid, in part, by William Hogarth, who argued that the S-curves and undulating lines of the Rococo were the foundations of beauty and grace in nature and art.

The Rococo style took its time in arriving in England. British furniture had followed the Palladian neoclassical model for a long time, under the designer William Kent. Kent was an influential figure who designed furniture for Lord Burlington. It was with Lord Burlington that Kent traveled to Italy between 1712 and 1720. Kent brought back Palladio ideas and models and designed the furniture for Chiswick House, Hampton Court Palace, and Holkham Hall among others.

The appearance of Mahogany in England around 1720 was the most significant Rococo development of the time. Alongside walnut wood, mahogany became popular for furniture. It was furniture designer Thomas Chippendale whose work was closest to the Rococo style. The catalog of designs for chinoiserie, Rococo, and Gothic furniture called the Gentleman’s and Cabinet-Makers Directory, was published by Chippendale in 1754. Although Chippendale’s furniture was certainly inspired by Rococo, he did not use inlays or marquetry in his furniture, unlike French designers.

Thomas Johnson was another important figure in British Rococo furniture. In 1761, Johnson published his own catalog of Rococo furniture designs, including furnishings based on Indian and Chinese motifs.

The Art and Design of the Rococo Period

As you have seen, there was a lot of variation in design within Europe. While South Germany fell for Rococo architecture, the English preferred Rococo furniture. Whether it is painting, sculpture, furniture, or architectural design, we can see the distinct Rococo style.

Rococo Interior Design

Interior design was the spark of the Rococo period. Although the Rococo style grew to dominate painting, sculpture, and even music, it started as a style of interior design. While the focus of architecture is typically on the external design, Rococo designers brought it inside. The height of Rococo interior design lies in the salon.

What Is a Rococo Salon?

The salon, much like a parlor or living room, is a room designed to entertain and impress guests. Initially designed for the wealthy aristocracy, the salon was a place to show off their incredible wealth and hold intellectual conversations. At the time, enlightenment philosophy believed that external architectural environments encouraged a particular way of life.

Rococo salons were central rooms decorated in the typically extravagant and luxurious Rococo style.

Salons featured the typical elaborate Rococo decorations, serpentine lines, light pastel colors, intricate patterns, asymmetry, and a lot of gold. The layout of salon rooms was often asymmetrical, a type of design known as contraste. Sculpted forms on walls and ceilings with abstract, leafy, and shell-like textures were interior ornaments.

The Salon de Monsieur le Prince is a particularly famous example. Another notable example of the Rococo salon is that by Germain Boffrand in the Parisian Hotel Soubise. These salons all have ceilings, walls, and molding with intricate decorations of S-curves, natural shapes, and shell forms.

Rococo Furniture

The salon was a way to reflect social status, and the furniture within the salon was another. During the Rococo period, there was an explosion in furniture making. Furniture designs emphasized the lightness of the Rococo period. Pieces of furniture were made to be physically lighter so that they could be moved around easily. Furniture also became more delicate and refined, with thin curved table legs.

Rococo furniture was free-standing rather than leaning against the wall. This feature also helped to add lightness and versatility to a room desired by the aristocracy.

Mahogany wood became a popular wood for Rococo furniture because it was strong. The strength of mahogany meant furniture makers could carve dainty furniture that would not break. Many specialized furnishings emerged during the Rococo period, including the voyeuse chair. Mirrors with ornately carved and decorated frames also became increasingly popular during the Rococo era. Interior designers would use mirrors to enhance the sense of light and spaciousness in a room.

Rococo Architecture: Baroque vs. Rococo

The 18th century Rococo architecture was more graceful, lighter, and more elaborate than Baroque styles. Although Rococo architecture was similar to Baroque designs in some ways, they differed significantly in others.

Baroque vs. Rococo Architectural Style

As with interior design and furniture, Rococo architecture emphasized design and form asymmetry, while the opposite was true for the Baroque style. Baroque architecture was altogether more serious, using religious themes from the protestant reformation, while Rococo architecture was more lighthearted, jocular, and secular. While Baroque buildings were designed for great public majesty, Rococo architecture emphasized privacy.

The Rococo curves and decorative elements we see in furniture and interior decoration also carried over into architectural design. The signature Rococo color palette of gold, white, and pastels was also a significant feature of Rococo architecture.

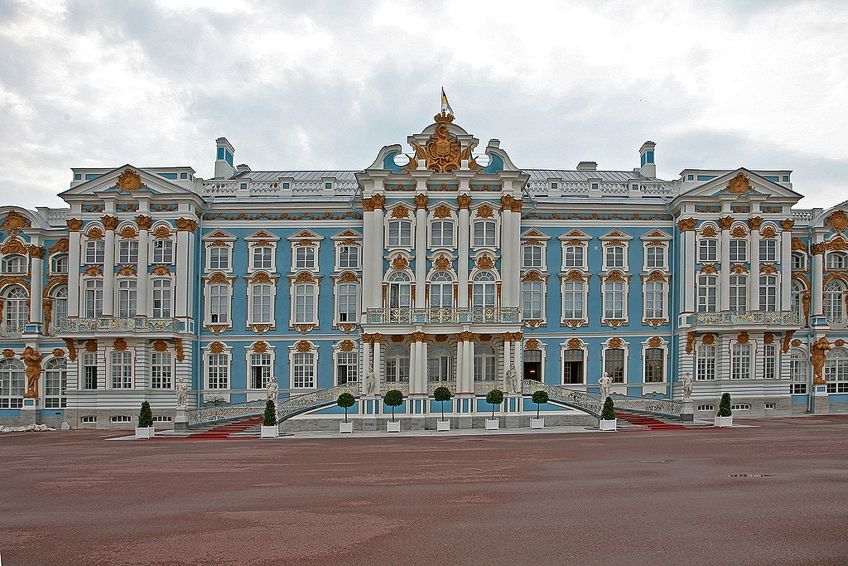

Some famous Rococo buildings include the Portuguese Queluz National Palace, the Catherine Palace in Russia, the Chinese House in Potsdam, the Falkenlust and Augustusburg Palaces, parts of the Chateau de Versailles, and the Charlottenburg Palace in Germany. The Italian architect Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli is known for his opulent and lavish designs and worked in Russia. Philip de Lange worked in both Dutch and Danish architecture, and Matthaus Daniel Poppelmann was a late Baroque architect who helped with the reconstruction of the German city of Dresden.

Rococo Painting

The delicate and light-hearted nature of Rococo design is perhaps most visible in the paintings of the era. Using the light Rococo palette of pastels, gold, and white, and other Rococo design elements like asymmetrical curves and serpentine lines, Rococo painting is easily distinguishable. Incredible attention to detail, playful themes, and a pastel color palette are significant Rococo painting features.

Impeccable Attention to Detail

Inspired by artists from the Renaissance, Rococo paintings have incredible attention to detail. The French artist Francois Boucher is particularly famous for his detail-oriented approach to painting. Boucher manages to capture the minute intricacies of ornate costumes and create beautifully detailed scenes.

Playful Subject Matters

Perhaps the themes of Rococo paintings best highlight the jovial atmosphere of this art period. Themes of youth, love, play, classical myths, idyllic landscapes, and portraits are typical of Rococo painting. The French painter Antoine Watteau is credited with making the playful Rococo subject matter popular. Watteau is known as the father of the fete galante genre of painting festivals, garden parties, and other outdoor events. Watteau painted scenes of pastoral landscapes and whimsical people socializing. Greek goddesses, cupids, and other mythological creatures often featured, blending reality with fantasy in a playful way.

The Rococo Color Palette

The color palette of Rococo-era paintings differs significantly from that of the earlier Baroque period. Baroque painters used deep and emotive colors, while Rococo artists like Jean-Honore Fragonard create lighthearted scenes with light pastel colors. Fragonard’s The Swing is one of the most famous paintings of the Rococo period. Light green swirls of foliage surround a woman in a light pink dress, flirtatiously flinging off her shoe as she swings.

Rococo Sculpture

The sculpture of the Rococo period was dynamic, theatrical, and colorful. A sense of movement in all directions permeates these sculptures. Sculptures were closely integrated with architecture and painting and could often be found inside churches.

Early French Rococo sculpture is much lighter than the classical Louis XIV style. Madame de Pompadour was a patron of Rococo sculpture, and she commissioned multiple works for her gardens and chateaux. A sculpture of cupid carving his love darts out of Hercules’ club is a famous Rococo sculpture by Edme Bouchardon. You can find other examples of Rococo sculpture around Versailles fountains, like the Fountain of Neptune by Nicolas-Sebastien Adam and Lambert-Sigisbert Adam made in 1740. Following their success, Frederick the Great invited these sculptors to create a fountain sculpture for his palace in Prussia.

Leading French sculptor Etienne-Maurice Falconet is best known for his St. Petersburg statue of Peter the Great, and he also created smaller works in terracotta or bronze for wealthy collectors. Falconet was not the only sculptor to produce smaller series of sculptures for collectors. Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, Michel Clodion, Jean-Louis Lemoyne, and Louis-Simon Boizot all created sculpture series.

Italian Antonio Corradini was one of the leading Rococo sculptors in Venice. He traveled throughout Europe, working in St. Petersburg for Peter the Great for a time and in Austrian and Napalese imperial courts. Corradini’s sculptures have a more sentimental feeling to them, and he made a number of dainty sculptures of veiled women.

Rococo Porcelain

During the Rococo period, small-scale porcelain sculptures began to emerge. Initially constructed to replace the sugar sculptures on large dining tables, porcelain figures soon became popular as decorations for mantlepieces. As the number of European porcelain factories grew throughout the 18th century, small porcelain sculptures became available to middle-class people. As the century progressed, the sheer amount of overglaze decoration on these colorful porcelain sculptures also increased.

The Meissen porcelain factory is the oldest in Europe and remained the most important until around 1760. Johann Joachim Kandler was the principal modeler at the Meissen factory. Franz Anton Bustelli, a German sculptor, worked at the Nymphenburg Porcelain Manufactory and was famous for his range of colorful figures that sold across Europe. Following his example, Etienne-Maurice Falconet became the director of the Sevres Porcelain factory. Here he produced various small-scale sculptures in series on themes of lightheartedness and love.

Rococo Music

Although Rococo music is not as well known as the later Classical and earlier Baroque forms, it has a place in musical history. The Rococo music style, like much of the Rococo movement, developed out of the Baroque era. In France, style galant, or the elegant style of music, was intimate music that was light, refined, and elaborate. Influential French Rococo composers include Louis-Claude Daquin, Jean Philippe Rameau, and Franscois Couperin. In Germany, the two sons of Johann Sebastian Bach, Johann Christian Bach and Carl Philip Emanuel Bach pioneered Rococo music or the “sensitive style”.

The second half of the 18th century saw a backlash against the overuse of decoration and ornamentation in the Rococo style. Christoph Willibald Gluck led this reactionary movement which eventually became the Classical style. The Variations on a Rococo Theme by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was composed in the style of Rococo, although it was not written during the Rococo era.

Rococo Fashion

The extravagance, refinement, ornamentation, and elegance of the Rococo style were not lost in Rococo fashion. Women’s fashion during the 18th century was sophisticated and highly ornate in true Rococo style. Beginning in the Royal Court, these fashions soon spread to the cafés and salons of the bourgeoisie.

Towards the end of Louis XIV’s reign, a flowing gown known as the robe volante became popular. A bodice, rounded petticoat, and large pleats flowing down the back were the prominent features of this dress. A dark and rich color palette of fabrics accompanied heavy and bold design features. Following the death of King Louis XIV, fashion styles began to change with the Rococo trends.

Rococo fashion was more frivolous, much lighter, and more revealing. A pastel color palette, an overabundance of bows, lace, frills, ruffles, and a lowcut neckline characterized Rococo women’s fashion. A new gown, known as the robe a la Francaise had a tight bodice and usually a large number of ribbon bows down the front. This dress had wide panniers and was decorated with lavish quantities of flowers, lace, and ribbon. Jean-Antoine Watteau, the painter who captures intricate detailing of stitching, lace, and other trimmings on ornate gowns, was the inspiration for Watteau pleats.

Around 1718, the mantua and pannier became fashionable. These were wide hoops that extended the hips sideways, worn underneath the dress. These items soon became essential staples in Rococo fashion. The iconic look of the Rococo era is the dress with extended hips and excessive amounts of decoration. Special occasions called for very wide panniers, some reaching up to 16 feet in diameter. Smaller hoops were for everyday wear.

This style of garment originated in 17th century Spain and was initially designed to hide a pregnant stomach.

The Golden age of Rococo fashion was around 1745 when a more oriental and exotic culture known as a la turque became popular in France. Madame de Pompadour was integral in promoting this style when she commissioned a painting of herself as a Turkish Sultana by Charles Andre Van Loo. The 1760s saw a less formal fashion style emerge. The polonaise, a shorter dress inspired by Polish fashions, made the ankles and underskirt visible. The polonaise dress also allowed women to move around with significantly more ease.

The robe a l’anglais, or English dress, was another popular style in the latter half of the 18th century. This dress included more masculine fashion elements like long sleeves, broad lapels, and a short jacket. A full skirt with a small train, but no panniers, a snug bodice, and a small lace kerchief around the neck completed the ensemble. A redingote, a combination of an overcoat and a cape was another new Rococo fashion item.

In addition to the multitude of different garments, accessories were an essential part of Rococo fashion in the 18th century. Accessories like necklaces and jewelry added to the opulence and decadent decoration on the gowns. Women in short sleeves were required to wear gloves at official ceremonies.

The Gradual Decline of the Rococo Style

It was not long until the Rococo emphasis on gallantry and decorative mythology inspired a reaction. The French Academy started teaching a more Classical style of art and De Troy, a prominent Classical artist, became the Academy’s director in 1738. Although the Rococo period was in decline in France, it continued to flourish in Austria and Germany.

Madame de Pompadour was a prominent and influential figure throughout the 18th century, promoting Rococo art and fashion, and contributing to its decline. In 1750, Madame de Pompadour sent her brother and several artists, including the architect Soufflot and engraver Charles-Nicolas Cochin, on a two-year trip to study Italian archeological and artistic developments. This group returned passionate about Classicism and Abel-Francious Poisson de Vandieres, Madame de Pompadour’s brother, became a Marquis.

Vandieres was also made the director-general for the King’s buildings and he was responsible for shifting French architecture towards the neoclassical. Cochin, an influential art critic denounced the style of Boucher, which he called petit style. Rather, Cochin called for a grander style of painting and architecture that emphasized nobility and classical antiquity.

Jacques-Francois Blondel and Voltair added their voices to the resounding criticisms of the superficial nature of Rococo art. The 1760s hailed the beginning of the end for the Rococo style, as artists began calling for art with purpose and value. Rococo had officially passed away by 1785 and was replaced with Neoclassicism.

The ridicule of Rococo as superficial and frivolous spread to Germany by the end of the 18th century. Although Rococo managed to remain popular in Italy and certain German states, it was thoroughly wiped out by the Empire Style second wave of Neoclassicism.

Famous Rococo Artists

There were so many painters, architects, and sculptors to emerge during the Rococo period. Of the many, there are a few that have made lasting impressions on the world of decorative art, including Francois Boucher, Elisabeth Louise Vigee le Brun, and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.

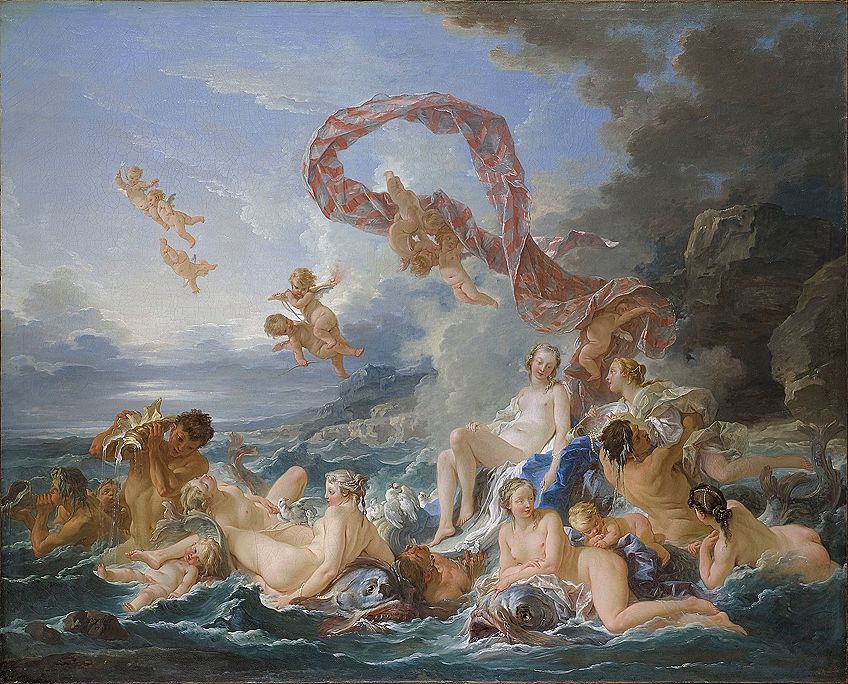

Francois Boucher (1703-1770)

Of all the prominent Rococo artists, Boucher certainly deserves a place on this list. Famous for his portrayals of ancient Roman and Greek mythologies, Boucher’s paintings shaped the course of the Rococo style. As a young art student, Boucher studied during the late Baroque period and traveled to Italy. He also studied the Dutch landscape style.

Boucher became very famous among French artists in his day. The voluptuous manner in which Boucher portrayed figures in his paintings earned him a significant amount of notoriety. Many of Boucher’s paintings featured shepherds and various forms of livestock in pastoral scenes. Of his works, the Triumph of Venus (1740) is thought to be his most famous, but it is in close contention with The Breakfast (1739) and The Grape Eaters (1749).

Jean-Honore Fragonard (1732-1806)

French Rococo printmaker and painter Jean-Honore Fragonard is one of the most famous painters from the Rococo period. Although he lived during the end of the 18th century, as Rococo began to decline, he created hedonistic paintings. During his lifetime, Fragonard also painted multiple works for the royal family, including The Meeting (1771).

Fragonard met Boucher when he was only 18 years of age, and although Boucher refused to work with Fragonard because of his lack of experience, he sent him to study with Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin. Despite his early lack of experience, Fragonard became one of the most prolific painters in French art history. A particularly famous Fragonard painting is The Stolen Kiss (1788).

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721)

Although he died before the Golden age of Rococo, Jean-Antoine Watteau was one of the most influential figures in the movement. It is Watteau who is credited with pioneering the Rococo style which he reached by integrating his own artistic flair with elements from masters like Peter Paul Rubens and Titian.

Watteau’s style was particularly colorful, with vibrant hues and a lot of depth. Many of Watteau’s works are typical of the Rococo style in their theatrical appearance. Watteau was also famed for his incredible ability to capture minute and intricate details, particularly in ornate garments. Perhaps Watteau’s most famous painting is Pilgrimage to the Isle of Cythera, which he completed in 1717. Other notable works include Pierrot (1719) and Embarkation for Cythera (1717).

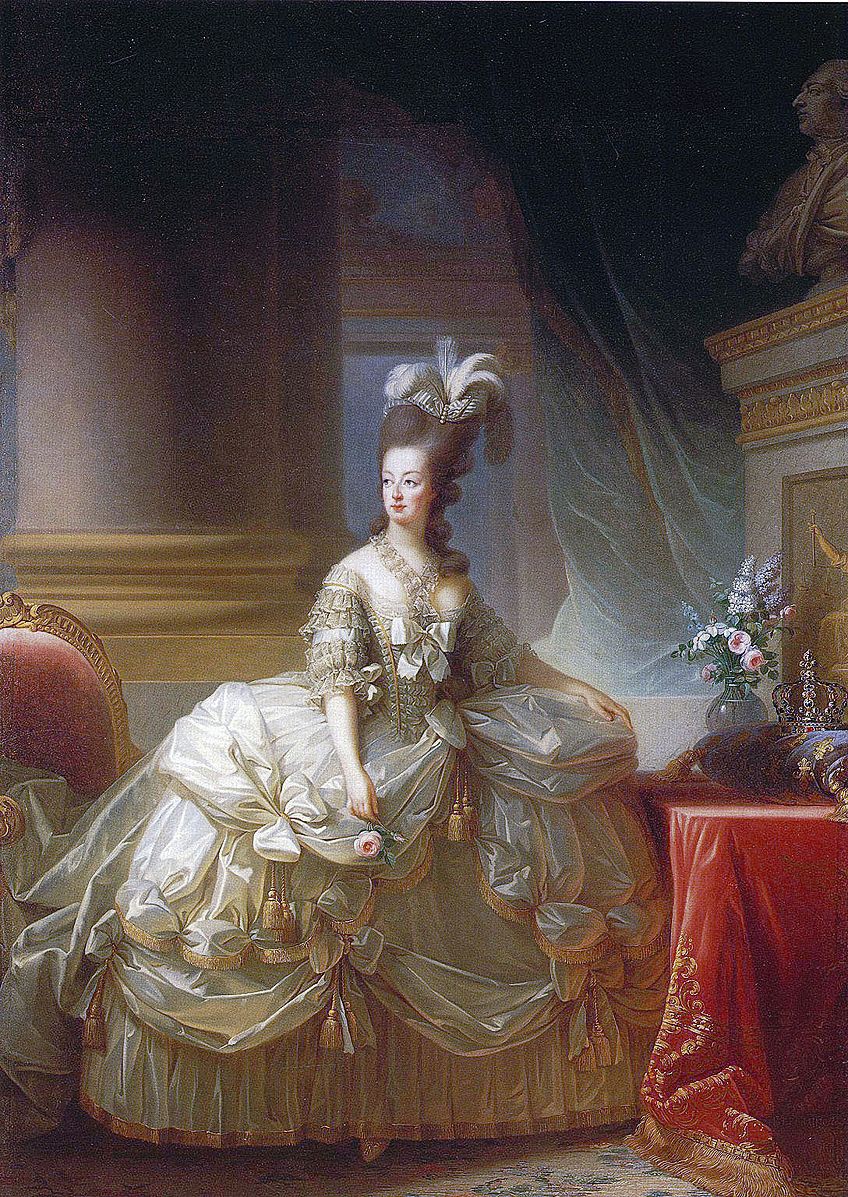

Elisabeth Louise Vigee le Brun (1755-1842)

One of the most prominent female artists in French history, le Brun is known best for her opulent portraits. When le Brun developed her artistic skill, she was not allowed to attend any of the formal art schools or academies. Fortunately, her father was an artist and he taught her to paint.

At just 15 years of age, le Brun began working as a professional painter. Despite the sexism of the day and the many who shunned her work, le Brun was placed in the Royal Academy at 28 years of age by King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. Le Brun went on to paint some of the most famous paintings in the history of France, with her most well-known piece being Marie Antoinette in a Court Dress (1778).

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696-1770)

A famed Venetian painter, Tiepolo is well-known for his highly decorative and overly elaborate paintings, often depicting royal figures. Tiepolo had a unique style during the Rococo period, having studied under several artists influenced by the High Renaissance. As a result of his education, Tiepolo’s style was a combination of Rococo and Renaissance.

Of his many works, The Marriage of the Emperor Frederick and Beatrice of Burgundy (1752) is probably his most famous. This incredibly significant historical event was portrayed in typical Rococo style. An opulently decorated hall with arches, flowing curtains, and elegantly dressed figures adorn the canvas of this famous painting.

Giovani Antonio Canal (1697-1768)

Better known as Canaletto, Giovani Antonio Canal was one of the most famous figures of 18th century Rococo. The Italian-born painter showed early artistic promise and became one of the most famous artists in both the Rococo and Venetian school movements.

Having traveled extensively throughout Europe during his life, Canaletto was well-known for his incredibly realistic cityscapes. Among the most famous paintings from his youth are The Entrance to the Grand Canal, Venice (1730), and The Stonemason’s Yard (1725). Canaletto completed both of these paintings as the Rococo movement was beginning to grow in France. It was thanks to the actions of Canaletto that Rococo spread to Italy.

Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788)

A prominent Rococo British artist, Gainsborough is best known for his intricately detailed portraits and elegant landscapes. Gainsborough was one of the most prominent members of the St. Martin’s Lane Academy, which was founded by Hubert Francois Gravelot after Rococo had crossed the channel from France.

Remembered as one of the most famous 18th-century British Painters, Gainsborough’s Rococo paintings are among his most celebrated. Although many of Gainsboroughs most loved paintings are landscapes, his most famous Rococo painting is The Blue Boy which he painted in 1770.

Full of opulence, gold, and extravagance, the Rococo style of the 18th century is immediately recognisable. Although the movement did not last very long, it certainly made an impression and many of the artists from this period remain important historical figures.

Take a look at our Rococo art webstory here!

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Rococo Art – Looking at the Luxurious and Light-Hearted Rococo Period.” Art in Context. February 26, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/rococo-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 26 February). Rococo Art – Looking at the Luxurious and Light-Hearted Rococo Period. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/rococo-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Rococo Art – Looking at the Luxurious and Light-Hearted Rococo Period.” Art in Context, February 26, 2021. https://artincontext.org/rococo-art/.