Romanticism Art – An Overview of the Romantic Movement

Around the turn of the 19th century, the Romantic movement began to emerge throughout Europe. The Romantic movement, which emphasized emotion and imagination, emerged in response to artistic disillusion with the Enlightenment ideas of order and reason. Romanticism encompassed art of all forms, from literary works to architectural masterpieces. Emphasizing the subjective, the individual, the spontaneous, irrational, visionary, imaginative, and transcendental, Romanticism rejected the style and notions of Neoclassicism.

Table of Contents

- 1 A Brief Summary of the Romantic Movement

- 2 The Development of Romanticism Art

- 3 Romanticism Literature

- 4 Romanticism in the Visual Arts

- 5 Music and Romanticism

- 6 Romantic Architecture: The Gothic Revival

- 7 Romanticism Throughout the World

A Brief Summary of the Romantic Movement

What is Romanticism? The spread of Romanticism throughout Europe and even the United States was rapid towards the late 18th century. Romanticism challenged the rational ideals so loved by artists of the Enlightenment. Romantic artists believed that emotions and senses were equally as important as order and reason for experiencing and understanding the world.

Following the French Revolution, the enduring search for individual liberty and rights fueled the Romantic celebration of intuition and imagination. The Romantic ideas of the subjectively creative powers of the artist continued to fuel Avant-Garde movements into the 20th century.

Romantic artists reacting against the somber Neoclassical style found their expression through music, literature, architecture, and visual art. The Romantic movement encompasses a variety of styles because it valued imagination, inspiration, and originality. Personal connections to nature and an idealized past were a significant theme for many Romantic artists attempting to hold back the waves of industrialism.

Key Romanticism Art Characteristics: A Romanticism Definition

You will already see that the Romantic movement was broad and far-reaching. Despite the variety of individual expressions encouraged by Romanticism, there are several key Romanticism characteristics, which underlie Romantic art. These include growing nationalism, subjectivity, plein air painting, and concerns with justice and equality.

Nationalism

The growing nationalism throughout Europe following the American Revolution was closely tied to Romanticism. You can see this nationalism in the emphasis on landscapes, traditions, and folklore in Romantic literature and art. Through the visual imagery in these works, Romantic artists fed a sense of national pride and identity. Many Romantic paintings are steeped in a call to spiritual renewal, which would continue ushering in a new age of liberties and freedom.

Subjectivity

One of the most significant elements of Romanticism was the increased emphasis on the personal and subjective power of the individual artist. The Neoclassical period, which preceded Romanticism, valued strict rule-based practices and logical thought in art. We can consider Romanticism as a direct reactionary response to the Neoclassical period.

Romantic artists began to explore different psychological, emotional, and mood states in their works. The Neoclassical obsession with genius and hero transformed into new ideas about the artist. Artists were able to express themselves fully, free from the tastes and rules of academic institutions.

Painting en Plein Air

Throughout Europe, Romantic artists began turning their attention to the natural world. With this growing fascination with nature, there was an increase in the practice of painting en Plein air, or outside. Artists would paint natural scenes by observing them directly. This process enabled artists to produce elevated landscapes. The close and intimate observation of the natural world translated into more emotive and atmospheric scenes.

Some Romantic artists painted scenes that emphasized humans as being one with nature. Other artists preferred to portray the powerful and unpredictable forces of nature in paintings that evoke feelings of awe and sometimes terror. Romantic artists harbored a deep appreciation for the beauty of the natural world.

Justice and Equality

Partly driven forwards by French Revolutionary idealism, the Romantic period embraced the fight for equality, freedom, and the advancement of justice. Many Romantic painters began painting scenes of current atrocities and social events. Dramatic compositions illuminated instances of injustice and rivaled the more rigid history paintings of the Neoclassical period.

The Development of Romanticism Art

At the end of the 18th century, German critics Friedrich and August Schlegal first used the term Romanticism in their article on “Romantic Poetry.” The term became popular in France in the early 19th century thanks to Madame de Stael, an influential intellectual French leader. She used the term in a published account of her travels in Germany in 1813.

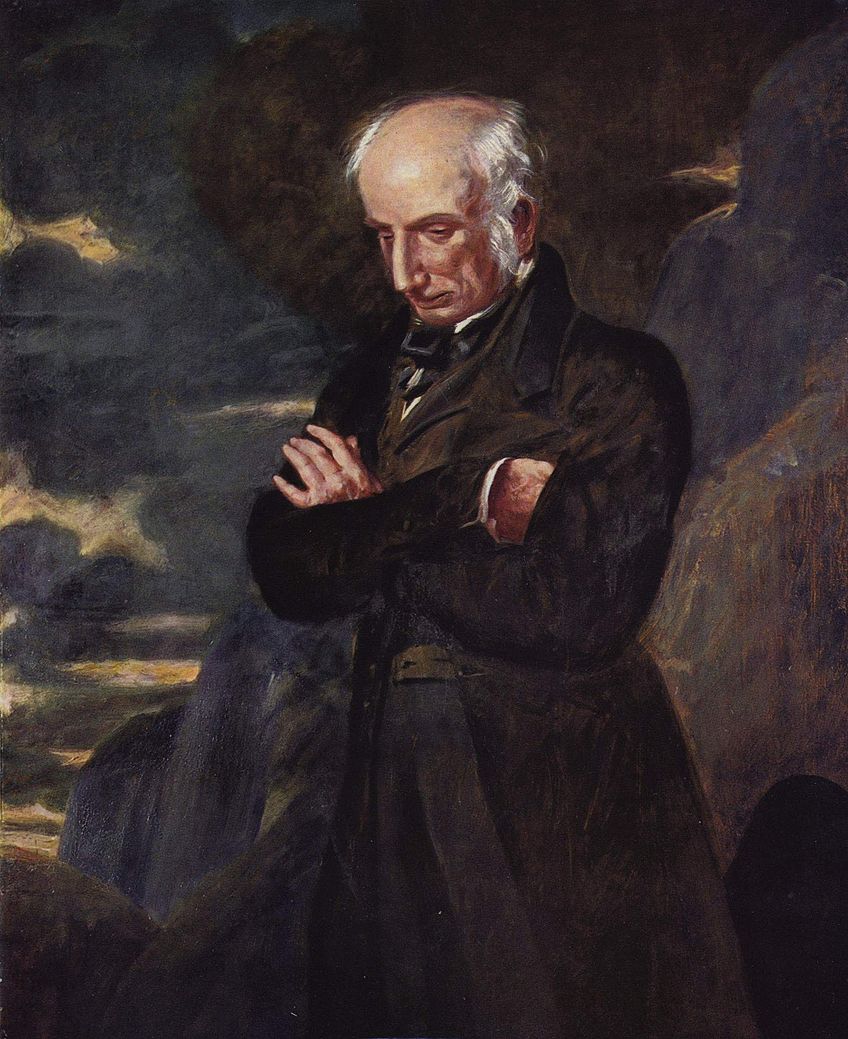

In England, the poet William Wordsworth was a significant proponent of Romanticism. Wordsworth believed that poetry was a natural expression of powerful emotions. Romantic artists shared an attitude towards humanity, nature, and art, but each was distinct in its unique expressions. The rejection of established orders, including religious and social systems, became a dominant theme of the Romantic movement. By 1820, Romanticism had firmly established itself throughout Europe.

Romanticism Literature

The earliest expressions of Romanticism were literary. The German movement Sturm und Drang, or Storm and Stress, was a precursor to Romanticism. This movement was primarily musical and literary and was popular between 1760 and 1780. Storm and Stress had a far-reaching influence on artistic and public consciousness. Romanticism was inspired by the title of a Friedrich Maximillian Klinger play called Romanticism (1777).

Pre-Romantic Literature: The Development of the Troubled Hero

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the German statesman, and writer was the most famous advocate for the growing Romantic movement. His novel The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774), a story about an emotionally anguished young artist who commits suicide when the woman he loves marries another, became a cultural phenomenon. Young men began adopting the clothing and mannerisms of the protagonist, and copycat suicides even occurred. As a result, some countries, including Italy and Denmark, banned the novel.

Although Goethe would later renounce his novel, the idea of an emotionally anguished young artist, a misunderstood genius, wormed its way into public consciousness. Many believe that the protagonist of this novel inspired the hero in Romanticism literature.

The preoccupation with the misunderstood emotional hero was strengthened further by the publication of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1812) by Lord Gordon Byron, the British Poet. This publication introduced the term “Byronic hero,” the brooding and lone genius figure, torn between their worst and best traits.

Romanticism Characteristics in Literature

It was through literature that many Romantic tropes were first developed, but what is Romanticism in literature? In England, France, and Germany, in particular, Romantic authors fueled the growing interest in subjectivity, the misunderstood genius, and nationalism. Here is a brief list of some of the most famous writers and poets from early Romanticism.

| English Romantic Writers | ● William Wordsworth ● Sir Walter Scott ● Mary Shelley ● Lord Byron ● William Hazlitt ● Percy Bysshe Shelley ● John Keats ● The Bronte Sisters ● Thomas De Quincey |

| French Romantic Writers | ● Alfred de Vigny ● Alfred de Musset ● Theophile Gautier ● Alexandre Dumas ● Victor Hugo ● Alphonse de Lamartine |

| German Romantic Writers | ● August Wilhelm ● Johann Wolfgang von Goethe ● Jean Paul ● Ludwig Tieck ● Wilhelm Heinrich ● Friedrich Schelling |

We begin to see the emergence of Romanticism in literature in the 1790s with Lyrical Ballads by William Wordsworth. The preface of this publication included the description of poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings,” which became somewhat of a Romanticism manifesto. This statement represented the Romanticism definition for early writers.

The poet William Blake was another founding poet of the first English Romantic phase. The first German Romantic phase included many innovations in literary style and content. A preoccupation with the subconscious, mystical, and supernatural also marked Romanticism. Writers including Jean Paul, August Wilhelm, Ludwig Tieck, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Wilhelm Heinrich, and Friedrich Schelling, were prominent during this first Romantic period in Germany.

The second Romantic period ran from 1805 until the 1830s. During this time, there was a very rapid increase in cultural nationalism, and artists and writers turned their attentions to national origins. Native folklore, folk music, folk dances, folk poetry, and ballads were collected and imitated extensively. Sir Walter Scott translated this revived historical appreciation into his imaginative writings. As a result, we often attribute the invention of the historical novel to him.

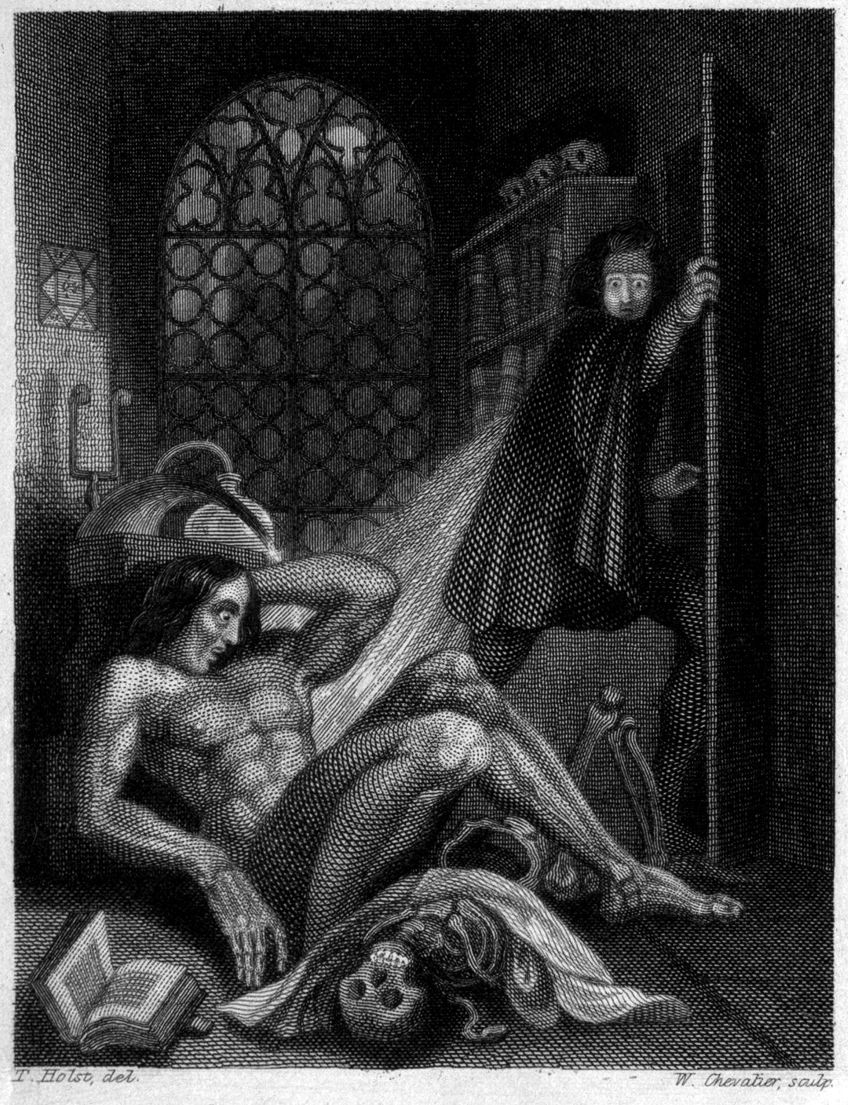

English Romantic poetry also reached its peak during this period, with the popular works by Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, and John Keats. Fascination with the supernatural was a fundamental characteristic of Romantic literature and tied into the interest with the subjective emotional world. Works like Frankenstein by Mary Shelley and other works by Marquis de Sade, Charles Robert Maturin, and E. T. A. Hoffmann explore this fascination.

The 1820s saw a significant broadening in the scope of Romantic literature, including that of most of Europe. Towards the end of this second phase, Romanticism was becoming increasingly nationalistic rather than universal. Authors began concentrating on their national and cultural histories, examining and exalting the struggles and passions of important historical figures.

The most prominent figures in Romantic literature are undoubtedly the English, French, and German authors we have already mentioned. There were, however, other significant authors from many European countries. In Italy, Giacomo Leopardi and Alessandro Manzoni were particularly influential. Angel de Saavedra and Jose de Espronceda dominated Spanish Romantic literature, while in Russia, Mikhail Lermontov and Aleksandr Pushkin were prominent figures.

Romanticism in the Visual Arts

The same fascination with emotional intensity, the supernatural, nationalism, and the hero trope in Romantic literature carry over into Romantic art. The visual art of the Romantic period also explored the natural world through landscapes and ideas of revolution and justice. Orientalism was also rife in a lot of Romantic painting, and it is possible to see the effects of Romanticism in the portraiture of the day.

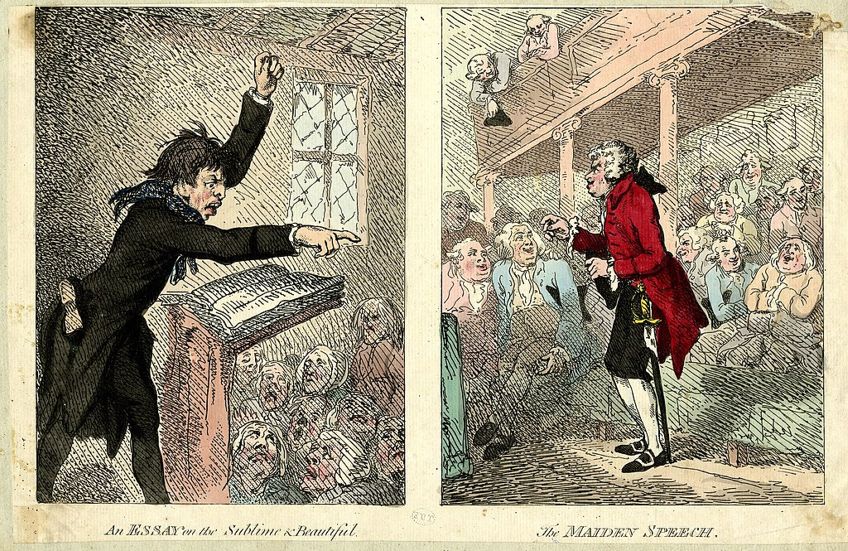

The Sublime: Stimulating the Romantic Mind

The Romantic era saw something of a great awakening to the philosophy of the mind. Philosophers, novelists, and visual artists alike began to explore the relationship between experience and the intricacies of the human mind. The sublime entered into Romanticism following the 1756 publication of Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful.

Part of the significance of these philosophical inquiries lay in their direct contradiction of Enlightenment rationality. The sublime was an experience whereby one views an object so beautiful and astonishing that we are unable to hold anything else in mind. Experiencing the sublime is more than the experience of beauty. Instead, it is to experience something so awe-inspiring that it overtakes our sense of objective reality. Experiencing the sublime is crucial to Romanticism painting because it triggers the necessary self-examination.

Romantic Landscapes: Romanticism Paintings and the Natural World

Many leading Romantic artists in England, the United States, and Germany focused their sights primarily on landscapes. Many Romantic artists attempted to capture the sublime in their landscapes. The natural world was one of the primary ways in which people could experience the sublime.

The overwhelming power and beauty of the natural world, be it the rolling thunderclouds of an approaching storm or an expansive landscape, can make the human mind consider its place in the world. Attempting to understand or perceive the formlessness, ungovernability, and boundlessness of the natural world leads to overwhelming emotions.

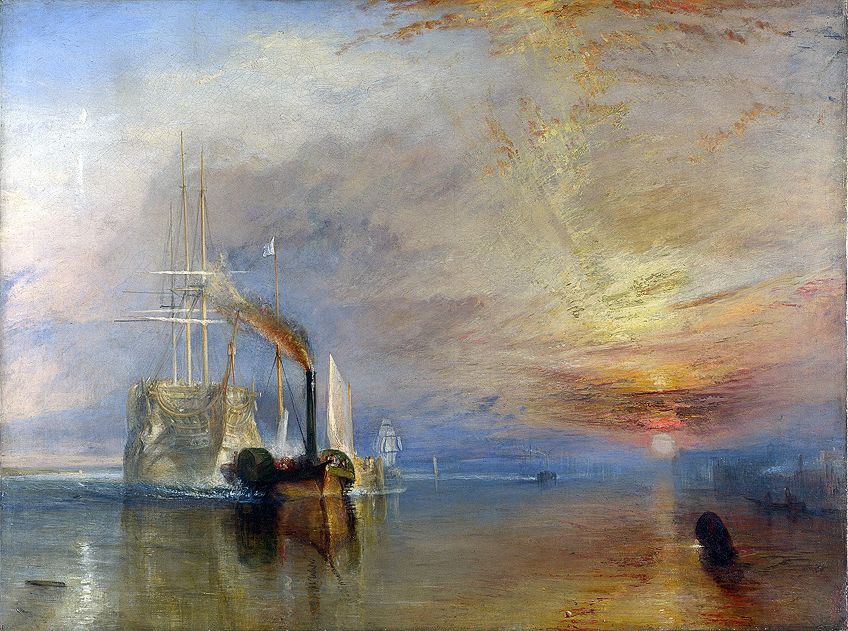

Shipwreck imagery was a common theme in many French and British Romantic landscapes. A shipwreck is a powerful representation of the overwhelming force of nature and human attempts to combat it. The uncontrollable power of the natural world offers a direct alternative to the structured and controlled world of Enlightenment philosophy.

According to Edmund Burke and Denis Diderot, the French philosopher, anything that “stuns the soul” and leaves us with a “feeling of terror” is a direct path to the sublime. Many art historians believe that shipwreck imagery culminated with the Raft of the Medusa (1819) by Théodore Géricault. This powerful scene is incredibly explicit, creating an overwhelming influx of intense emotionality. The conspicuous lack of a hero within the scene made this painting an iconic representation of Romanticism.

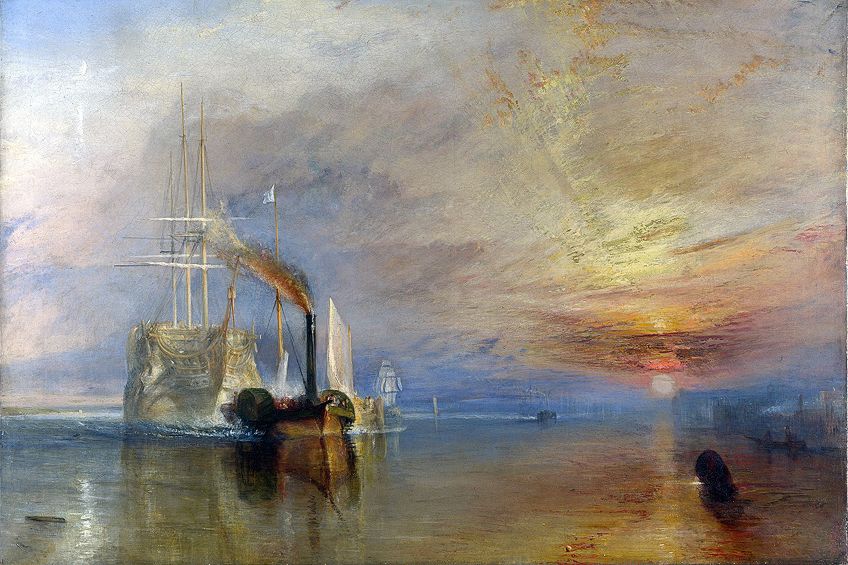

English Romantic painters were some of the most prominent landscape artists within the movement. Artists like John Constable and J. M. W. Wiliam Turner encapsulate the Romantic fascination with the natural world, and they are able to capture the power and unpredictability of its beauty.

The dramatic and transient effects of color, light, and atmosphere in these works capture the dynamism of the natural world and evoke a sense of grandeur and awe. Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps (1812) by J. M. W. Turner is a famous composition that dwarfs the human experience in the face of nature’s power. Three or four figures are engulfed within a large, swirling storm of snow, utterly dwarfed by the forces beyond their control.

The landscapes of John Constable highlight another key Romantic attitude towards nature. John Constable’s landscapes express his individual relationship to his native English countryside. Other artists and critics embraced Constable’s works as “nature itself” in an 1824 exhibition at the Parisian Salon. The high level of subjectivity and attention to the landscapes highlight the ingrained sense of individuality in Romanticism.

The Animal Kingdom

While Romantic landscapes rarely included human forms, they often featured various members of the animal kingdom. In fact, many Romantic painters represented animals as metaphors for human behavior and forces of nature.

The 1820s saw artists like Edwin Landseer and Delacroix Antoine-Louis Barye creating sketches of wild animals in the London and Parisian menageries. Gericault was another Romantic artist fascinated with members of the animal kingdom, and he had a particularly soft spot for horses. From racehorses to workhorses, Gericault depicted horses extensively in his work. For artists like Théodore Chassériau and Delacroix, Lord Byron’s story of Mazeppa tied to a wild horse inspired depictions of passion and violence.

Mazeppa and the Wolves (1826): Horace Vernet

In the 1827 Salon, Horace Vernet showed two scenes directly from Mazeppa. This particular composition depicts part of the legend of Mazeppa. In this scene, after being found to be having an affair with a countess, her husband ties Mazeppa naked to the back of a horse. The horse carries him down to the very bottom of the steppes in Ukraine. According to the legend, and depicted in the painting, the hero was attacked by a pack of wolves on his journey.

The Hudson River School

In America, Romantic landscapes cannot be separated from the Hudson River School. American Romantic painters found inspiration in the wild and rugged American terrain and the Transcendentalism philosophy. The landscapes by American Romantic period artists tend to be highly detailed, vivid, and often idealized natural scenes.

Painters who used this style were members of the Hudson River School. The group was founded by the famous landscape painters, Thomas Cole. The second group of Hudson River landscape painters came from New York. These artists ventured out into the wild landscapes of the West. All Hudson River Romantic painters shared the desire to capture the majesty and sublimity of the natural world.

The Voyage of Life (1840): Thomas Cole

In 1840, Cole painted a four-part series of landscapes. These landscapes, with a Romantic backdrop, serve as a Christian allegory for the four stages of a man’s life.

The first painting is Childhood, and it sets the stage for the entire series. The composition shows a baby exiting a dark canal on a small boat bathed in light. The water below is smooth and calm, and a soft white light bathes the landscape around the child. At the tiller of the boat is a guardian angel, gently guiding the child out onto the water.

The second painting is called Youth. The composition remains the same as the first painting, and the surroundings continue to be lush and peaceful. The stark difference between the first and second painting is the guardian angel leaving the boy on his own. The young boy eagerly grabs the tiller and sets off towards his ambitions and dreams. A youthful innocence still permeates this painting, but just beyond the river’s bend, the water begins to get choppy. Hints of a more troublesome and difficult journey towards his dreams lay ahead.

Manhood is the third painting in this series. A grown man replaces the young boy on the boat. The peaceful and luscious countryside on either side of the riverbank is gone, and the skies have grown dark. The waters are choppy, and large jagged rocks line the edge of the water. The boat is missing its tiller, and the man is no longer in control.

From a distance, he is still watched by his guardian angel where the man cannot see her. He must continue to have faith that she is watching over him. According to historians, Cole wanted to communicate how the idealism and dreams we have when we are young come crashing down in adulthood. The ocean that begins to appear in the distance, symbolizes the end of the man’s life, and the warm red hues of the sunset hint at hope despite his trials.

The final painting in this series is called Old Age. The angel returns to the side of the now old man. His boat now sits on the expansive ocean, and the waters are smooth and calm once again. Light is beginning to break through the dark clouds in the sky, and the man’s faith has carried him safely through the trials of his life. The beauty of eternity now awaits him.

Romantic Portraiture

The Romantic interest in internal, subjective states is possibly best captured in their portraiture. While traditional, Neoclassical portraiture aimed to capture the likeness of an individual, Romantic portraiture was far more interested in the psychological and emotional states of the individual.

Gericault explored emotional anguish in the extremes of mental health through portraits he painted of psychiatric patients. The emotionality that Gericault is able to capture represents the epitome of the Romantic interest in the wild and subjective. Gericault also explored the darker sides of childhood.

Alfred Dedreux (1810-1860): Théodore Géricault

This portrait is one of the best examples of Gericault’s portraiture of young children. The portrait is of a young boy called Alfred Dedreux, the nephew of Pierre-Joseph Dedreux-Dorcy, a good friend of Gericault. Although the young boy is only about five or six years old, he appears to be an adult. His face carries a seriousness of a grown man, and the dark background with heavy and ominous clouds communicates feelings of unease.

History Painting

While Romanticism paintings rejected almost everything from the Neoclassic era, Romantic period artists repurposed the History painting. Romantic artists discarded the pedantic rules and regulations of Neoclassical history painting in favor of more exotic subjects.

While the Romanticism we have spoken about so far has been primarily concerned with depicting scenes of high emotionality, lack of human control, and the sublime, oriental, and glorified images were also an essential part of the movement’s oeuvre. Many of the paintings we discuss here would not be appropriate today, following Edward Said’s study of Orientalism. It is possible to find Orientalism in both Romantic painting and literature.

Eugene Delacroix, the most famous French Romantic painter, visited Morocco in 1832, and this trip prompted many other Romantic artists to follow suit. Delacroix is famous for his expressive and free brushwork, dynamic compositions, adventurous and exotic subject matter, and sensual use of color.

Following the example of Delacroix, Chasseriau visited Algeria in 1846, and we can follow his journey through his notebooks full of drawings and watercolors. These preliminary studies would later inspire many paintings produced in Paris.

The exaggerated exoticism of the Eastern World by European artists began in the Renaissance period. You can see this early development in The Reception of the Ambassadors in Damascus (1511). In Oriental paintings like this one, the artist attempts to create a scene that captures and glorifies the exotic nature of these Middle Eastern countries. These scenes, however, tend to cross the line between glorification and caricatures. Many of these paintings are deeply offensive to the cultures they portray.

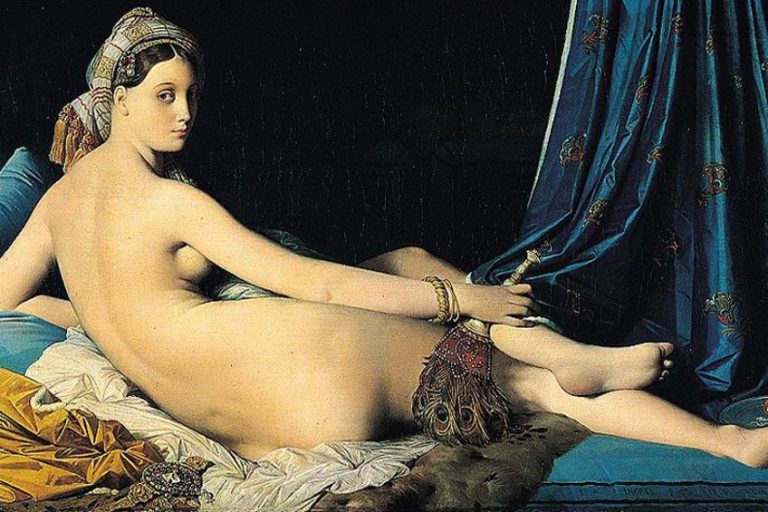

The fascination with Middle Eastern subjects grew in popularity during the Romantic era, with paintings of nude women like Grande Odalisque (1814) by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and The Women of Algiers (1834) by Delacroix. These paintings project the fears and desires of the artists onto the Middle Eastern and African scenes.

The Women of Algiers (1834): Eugène Delacroix

When this painting was first shown in Paris in 1834, it caused a great stir. Not only were the highly sexual connotations shocking to Parisian society, but the painting also portrayed the use of opium. At the time, opium was only portrayed in works featuring prostitutes.

This painting was also notorious because of the way Delacroix was able to paint Muslim women, whose coverings made them tricky to paint. Delacroix’s secret was that he was able to sketch some of these women during his 1832 visit to Morocco. Despite the sensation, King Louis Philippe purchased the painting and presented it to the Luxembourg museum. It now hangs in the Louvre, alongside many of his other masterpieces.

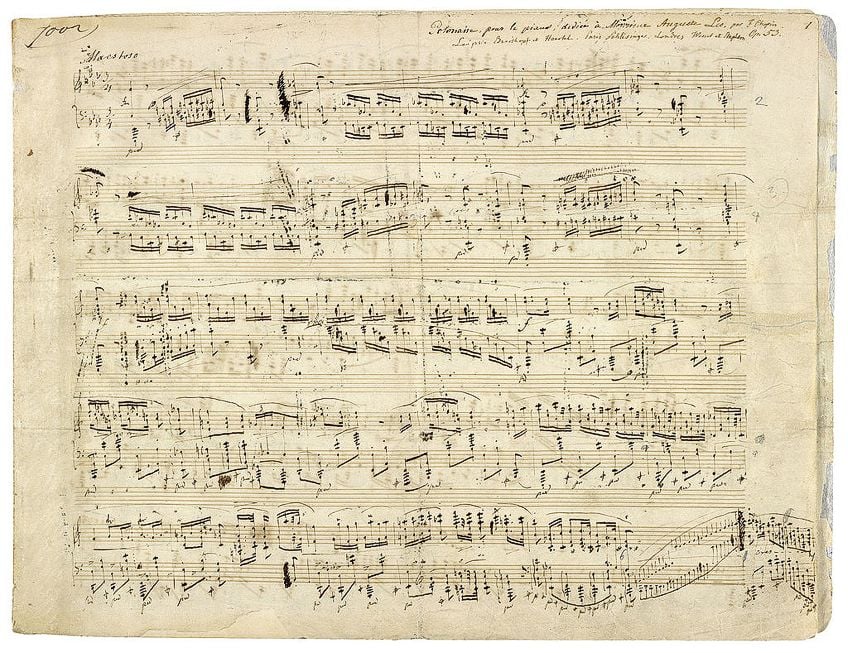

Music and Romanticism

As in literature and the visual arts, Romantic music emphasizes individuality, subjectivity, emotional expression, and freedom of expression. Two composers, in particular, bridged the gap between the Romantic and Classical periods. These two musical artists are Franz Schubert and Ludwig van Beethoven. For some time, the musical techniques used by these two were strict and formal, and very classical. It was, however, their use of programmatic elements and communication of intense emotionality that set the stage for music in the Romantic era.

Romanticism influenced the musical world in several ways. Romantic composers took the opera to new heights, and there were many innovations in musical instruments that allowed musicians and composers to create new possibilities of dramatic expression.

Romantic Opera

Romantic opera began in Germany and Italy consecutively. In Germany, the works of Carl Maria von Weber sparked Romantic opera and culminated with the works of Richard Wagner. Wagner combined various diverse elements of Romanticism into his operatic works. From the cult of the hero to the fervent nationalism, expressive music, exotic costumes and sets, and the virtuosity in vocal and orchestral settings.

In Italy, Gioachino Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini, and Gaetano Donizetti were the leading composers of Romantic opera. While these composers developed the Italian Romantic opera, it was through Guiseppe Verdi that it reached its pinnacle.

Developments in Musical Instruments

Without innovations in the instrument repertoire, Romantic composers could not bring their dreams to fruition. The perfection and expansion of the instrumental repertoire allowed composers to reach new levels of dramatic expression. Composers were able to express their unique subjectivity and intense emotionality through music in very new ways, thanks to the creation of new musical forms. These forms include the nocturne, capriccio, mazurka, prelude, intermezzo, and lied.

Romantic composers often found inspiration in national folk tales, poetry, and legends. Many strung together music and words through forms like incidental music, the concert overture, and programmatically. These are unique features that distinguish Romantic music.

The first phase of Romanticism was dominated by many famous composers, including Felix Mendelssohn, Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt, and Frederic Chopin. Each of these composers expanded the vocabulary of harmony to the very limits, exploiting the full range of the chromatic scale. They also pushed orchestral instruments to the boundaries of their expressive abilities and explored the linking of the human voice and instrumentation.

During the middle Romanticism phase, composers like Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Edvard Grieg, and Antonin Dvorak dominated the music scene. These composers created complex, unique, and highly emotive pieces. The nationalism within Romanticism began to permeate music during this phase.

Composers like Bedrich Smetana and Dvorak integrated national folk melodies with highly expressive musicality, creating fantastic and powerful works. Composers like Jean Sibelius, Edward Elgar, Richard Strauss, and Gustav Mahler tied up the final phase of Romantic music.

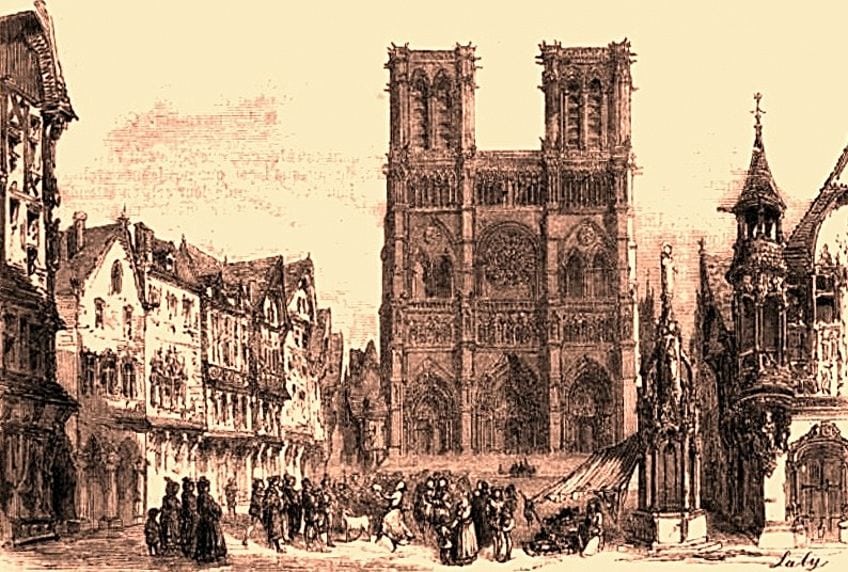

Romantic Architecture: The Gothic Revival

Just as in art, literature, and music, Romantic architecture rejected the ideals of Neoclassical design. The primary way that Romantic architecture undermined the Neoclassical style was by referring to historical styles. Romantic architects used styles from various countries and eras to evoke feelings of exoticism and nostalgia. A revival style, like that of the Oriental Revival and Gothic Revival, dominated Romantic architecture.

As early as the 1740s, architects began incorporating Gothic design elements. It was, however, only in the 1800s that the Gothic Revival grew in popularity. The Victor Hugo novel, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831) and instigated the popularity of Neo-Gothic architecture. Perhaps the clearest British example of the Gothic Revival is the Houses of Parliament. These buildings were designed and rebuilt by the architect Charles Berry and A. W. N. Pugin.

Romanticism Throughout the World

Romanticism began in Germany but before long it was popular throughout America and many European countries. Each country had its own unique expression of Romanticism, informed by the national culture and history.

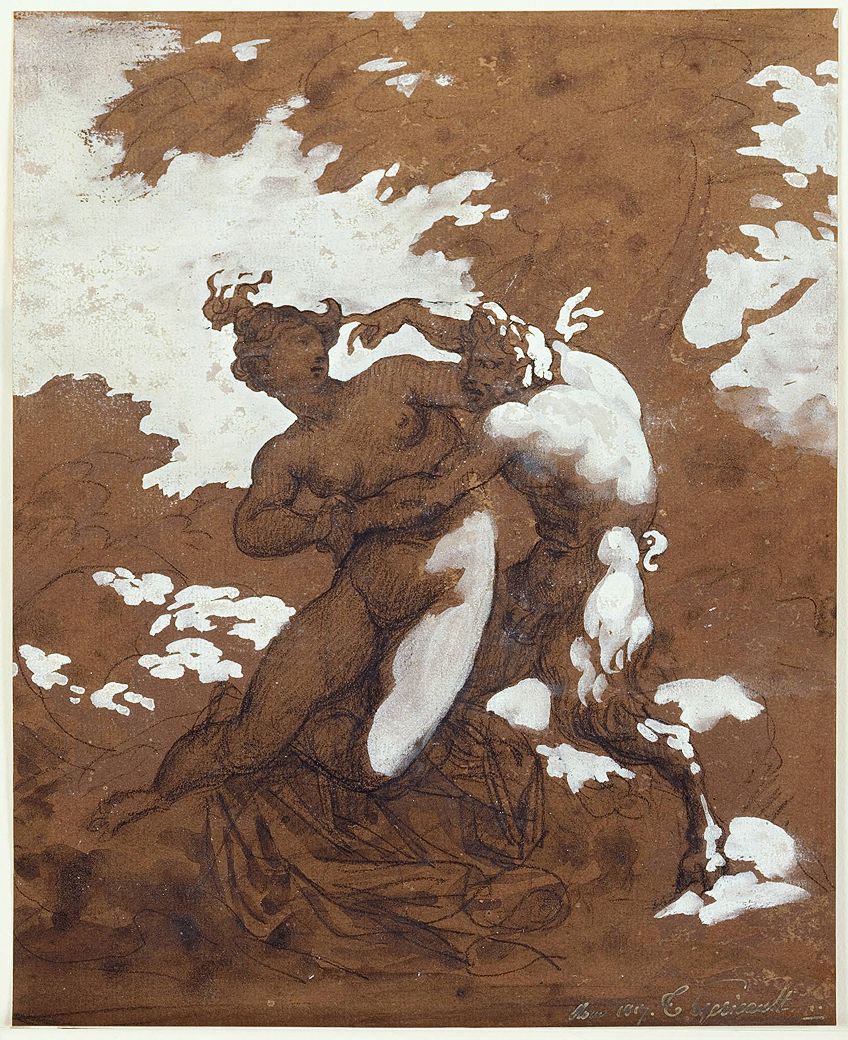

French Romanticism

Romantic painters began challenging the Neoclassical techniques of Jacques-Louis David following the Napoleonic Wars and the exile of Napoleon. Unlike German Romantic artists, the French had a much wider repertoire of subjects, including history painting and portraiture. Artists like Eugéne Delacroix and Jean-Léon Gérome ushered in an age of Orientalism with their colorful and dramatically staged compositions of different parts of North Africa.

French Romantic artists also experimented with sculpture. Géricault, in particular, experimented with sculptures, including an 1818 piece called Nymph and Satyr, which presented a violent and suggestive meeting between two mythological creatures. Animals were the most prominent subjects for French Romantic sculptures.

Artists were able to capture the violence and aggression of savage beasts with such delicate beauty. These works are some of the best examples of art attempting to reach the sublime by creating scenes of terror and awe. Antoine-Louis Bayre is the most famous French animal sculptor.

English Romanticism

In England, Romanticism was seen most prominently in literature and landscape paintings. Unlike the dramatic landscapes favored by German painters, English landscape artists were much more naturalistic. From 1803, the Norwich School group of landscape artists was founded. John Crome was a prominent founding member. This group held annual exhibitions between 1805 and 1833. Many members of the group, including Crome, practiced painting en plein air.

When discussing English Romantic landscapes, we cannot ignore the influence of John Constable. As one of the foremost Romantic landscape painters, Constable infused a deep sensitivity into his close observation of nature. Eugene Delacroix was heavily influenced by the way Constable used dabs of white and local color to imitate glimmers of light.

When it comes to color use, J. M. W. Turner was the most radical Romantic artist. Turner was reclusive and eccentric and worked in prints, watercolor, and oil. Using rapid strokes of color, Turner was able to create dynamic compositions with stunning light effects.

American Romanticism

The center of Romantcicism in America was the Hudson River School. Between 1825 and 1875, American Romantic painters found their primary expression through landscape painting. Cole is certainly the most well-known member of the group, but it began with Thomas Doughty. The work of Doughty emphasized a quiet stillness in nature.

Frederic Edwin Church was also an influential member of this group of landscape artists, alongside Asher B. Durand and Albert Bierstadt. Most of these artists focused on painting the Catskills, White Mountains, and Adirondacks of the American Northeast.

Gradually, American Romantic artists began moving towards Southern and Western America and the landscapes in Latin America. Like many English landscape artists, American Romantic painters used sketches completed outdoors to create paintings within their studios. American Romantic landscapes are often highly dramatic, overwhelming, and awe-inspiring vistas.

Romanticism was a natural reaction against the strict, dogmatic rules of the Neoclassical period. In the face of Enlightenment ideals that valued rational thought and logic, Romantic artists emphasized emotionality, uncontrollable nature, and the subjectivity of each individual. These Romantic characteristics permeated all forms of art in the 18th century, from literature to music, visual arts, and architecture.

Take a look at our Romantic art webstory here!

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Romanticism Art – An Overview of the Romantic Movement.” Art in Context. April 28, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/romanticism-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 28 April). Romanticism Art – An Overview of the Romantic Movement. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/romanticism-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Romanticism Art – An Overview of the Romantic Movement.” Art in Context, April 28, 2021. https://artincontext.org/romanticism-art/.