Pre-Raphaelite Art – A History of the Pre-Raphaelitism Art Period

The inflexible conventions of classical art, combined with the social unrest that was arising as a result of large-scale industrialization set the scene in the mid-19th century for a rebellious group of young artists to express their discontent through an art movement they formed called the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. It challenged the values of classical Victorian art by reviving the methods and ideals of Renaissance and Medieval art.

Table of Contents

What Is Pre-Raphaelite Art?

Like any art movement that has carved itself into the annals of time, Pre-Raphaelite art was associated with the social, political, and economic changes of Victorian England. On a societal scale, it was a response to the widespread industrialization that was sweeping across the UK, which was responsible not only for poor working conditions, wide-scale suffering, and diminished quality of life, but also for the demise of the old-fashioned connection to nature, spirit, and heart. It was this connection to nature and the self that the artists of this movement associated with the art that pre-dated the work of Raphael.

Beyond the social unrest and fundamental changes that were taking place throughout the country in the wake of industrialization, we must turn our attention to the theory that was being promoted within the walls of the Royal Academy of London to see the main reason this art movement surfaced when it did. Although perhaps inspired and informed by the unpredictable changes happening around them, this movement was not a direct outcry against the injustices of society – rather, on a smaller scale, it was a response to the artistic values imposed by the Royal Academy.

The principles that were the object of enough distaste to inspire an artistic revolution were based on the clearly defined styles and biases of the president of the Royal Academy at the time, Joshua Reynolds. An artist himself, Reynolds focused his work on painting genres and portraits that celebrated classical Greece and Rome.

In challenging the stagnant ideals embodied in this style of art, the brotherhood sought to bring life into the art world by allowing artists the freedom to create their masterpieces without conforming to the authority of the Academy for its own sake.

Pre-Raphaelitism was the brainchild of three young rogue painters – Dante Gabriel Rosetti, William Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais, all of whom found themselves disillusioned by what they believed to be the stuffy conventions of the Academy as a microcosmic artistic reflection of the values of a society. To them, the soul of the working class was being buried beneath the ruthless reach of industrialization, and that there was an associated severing of the common man from meaningful work and relationship with himself and nature.

As described by Dante Rosetti, this secret society aimed to create high-quality art that expressed real ideas and that sympathized with the genuine, heartfelt aspects of historical artworks without entertaining the superficial, vain, and conventional qualities of previous art from which they drew inspiration. A large part of the goal was also to portray nature as accurately and in as much detail, as possible.

For this reason, the artists believed that painting outdoors was the best way to capture the changing natural environment. They were inspired by the writing of art critic John Ruskin, who later became one of their most ardent supporters: “to go to nature in all singleness of heart…rejecting nothing, selecting nothing and scorning nothing”.

This was one of the defining features of their approach to their work, which set them and their work apart from the traditional method of painting indoors after a preliminary sketch.

This was in response to the highly selective and biased depiction of nature in Victorian art, and its insistence upon creating sketches from nature that would be transmuted to painting in the confines of indoor settings. Hence their desire to work en plein air, outside in the natural environment to capture the essence of nature, became a characteristic that had a strong influence on the evolution of landscape painting.

The artwork belonging to this art movement was not limited to painting, but included poetry, literature, sculpture, photography, and influenced, in its later years, decorative art, interior design, architecture, and illustrations. Many of the artists who belonged to the brotherhood were poets or drew from literature to inspire their paintings.

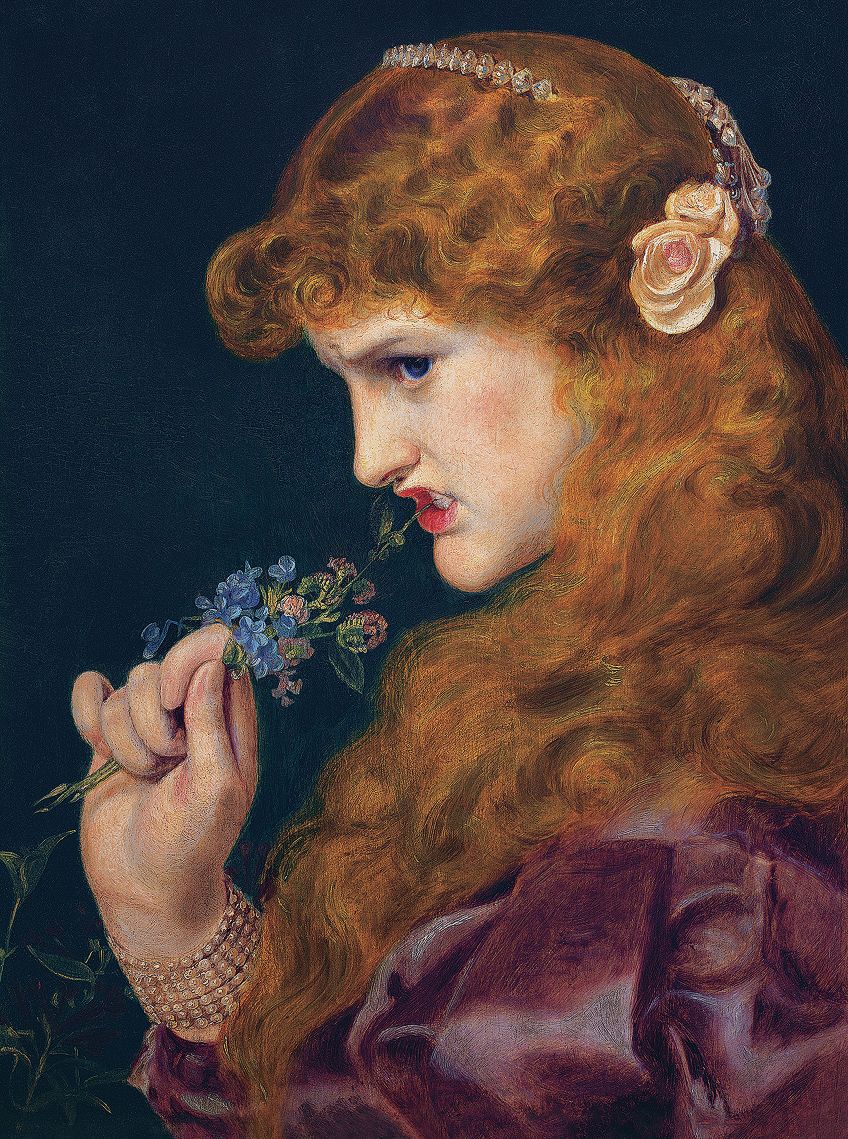

Many of the paintings that emerged in this art movement also challenged what the artists believed to be outdated conceptions of femininity. Some of the paintings portrayed important female (sometimes archetypal) characters from literature. The figures themselves were often drawn from real-life models.

Themes that appeared in such paintings were often topics that brought uncomfortable topics, such as sex and death, to the fore. The portrayal of women in these paintings gives women more power and naturalness in a cultural climate in which women were seen as weaker than men, and whose roles and identities were limited to those of wife, mother, and housekeeper.

Although it landed a well-deserved place in the history of art, it was never a formal movement officiated by a written manifesto as some of the more formal artistic movements were.

Taking into account their general disdain for the norms of academic art at the time, as well as their unapologetic portrayal of alternative perspectives, it is not hard to imagine that the brotherhood came under intense scrutiny and criticism from other artists and critics of the time.

Characteristics of Pre-Raphaelite Artwork

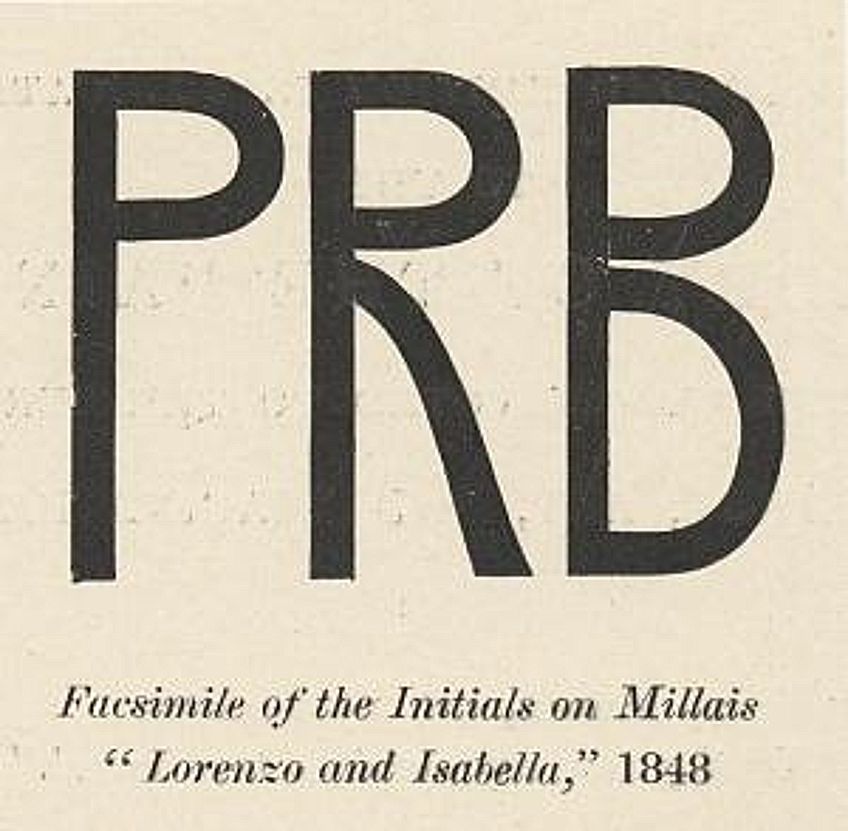

Aside from the tell-tale mark of the brotherhood in the form of the mysterious “P.R.B” signature on some of the early paintings, and of course the more personal signatures of the painters, there are several characteristics that defined this type of art and indeed, that make Pre-Raphaelites’ paintings fairly easy to identify based on the physical features of the paintings.

In particular, the brotherhood artists had a certain disdain for the Victorian obsession with portrait and genre paintings, which was characteristic of Reynolds. But their rebelliousness was not limited to the subjects of their art; it included style, techniques used, and values embodied in the paintings.

For example, it was typical for contemporary artists of the period to garb their subjects in the attire and place them against a nostalgic backdrop of classical Greek and Roman sentiment. Reynolds’ method became known as “the Grand Manner”. While it can be said that the brotherhood art also emanated a nostalgic mood, theirs was toward a time that came before Raphael, reminiscent of medieval times and the Italian Renaissance which resembled, in the eyes of the brotherhood, a purer form of art.

The figures in the Victorian paintings that members of the brotherhood so despised, many of them women, not only bestowed upon the viewer vision of ancient times but they also bore the burden of being anchored to stale stereotypes of women as chaste and incompetent, or mothers whose skills were useful only in the confines of the household. And, generally speaking, art in this movement had a certain gravity to it; there was a sincerity that made it different from other styles in an intangible, emotive way.

In terms of the techniques used by members of this movement, the luminous, almost two-dimensional use of color and simple line that was characteristic of many paintings in this movement is a stark contrast to the conventional emphasis of light versus shadow (this technique is known as chiaroscuro) that was popularly used at the time. This art also tends to ignore the pedantic inclusion of symmetry and proportion in composition.

The unique coloring of-Pre Raphaelite paintings was sometimes achieved by what became known as the “wet-white-ground technique”, which entailed painting a thick layer of white paint, and painting color over it while it was still wet.

Notable artworks

History is adorned with hundreds of beautifully detailed pieces of art from this movement. The paintings described below are a trio of paintings from the three founders of the Pre-Raphaelitism and examples of some of the most well-known pieces from this seminal art movement.

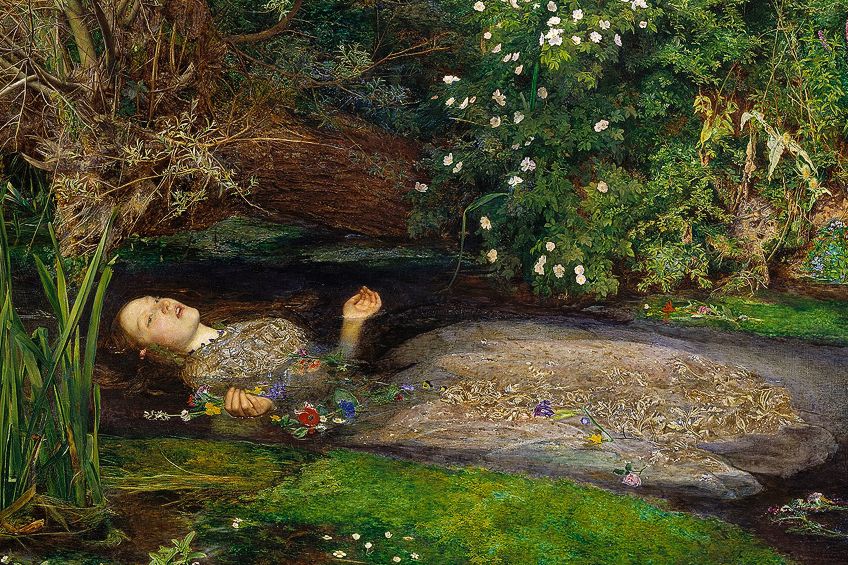

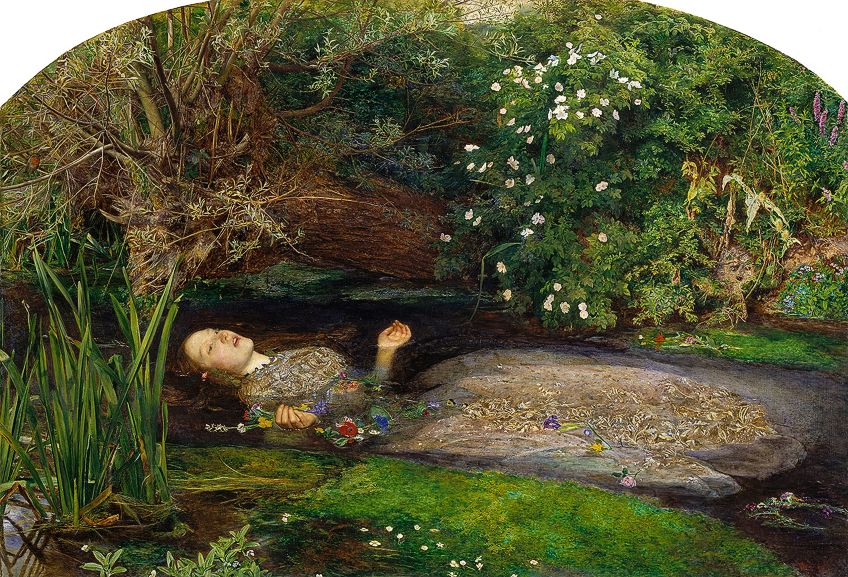

Ophelia (1851 – 1852) by John Everett Millais

Ophelia is possibly one of the most famous paintings to make it out of the brotherhood and to reflect the artists’ interests in bringing to light an unadulterated reality that forced people to confront the human condition in its full range of experiences, even though some of those topics were taboo.

Depicting a famous scene from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, in this painting we find Ophelia floating in what would be her watery grave. The famous scene shows Ophelia in the fateful moments between the time she falls into the water, floating in her madness unaware of the encroaching danger of being drowned by the weight of her dress.

This painting surrounds Ophelia with a highly detailed natural environment, with foliage that took at least as long to paint as the time the artist spent on creating the extremely life-like representation of Ophelia herself. This can be contrasted with the emphasis placed by conventional artists on the importance of the figure, at the expense of the natural background or setting.

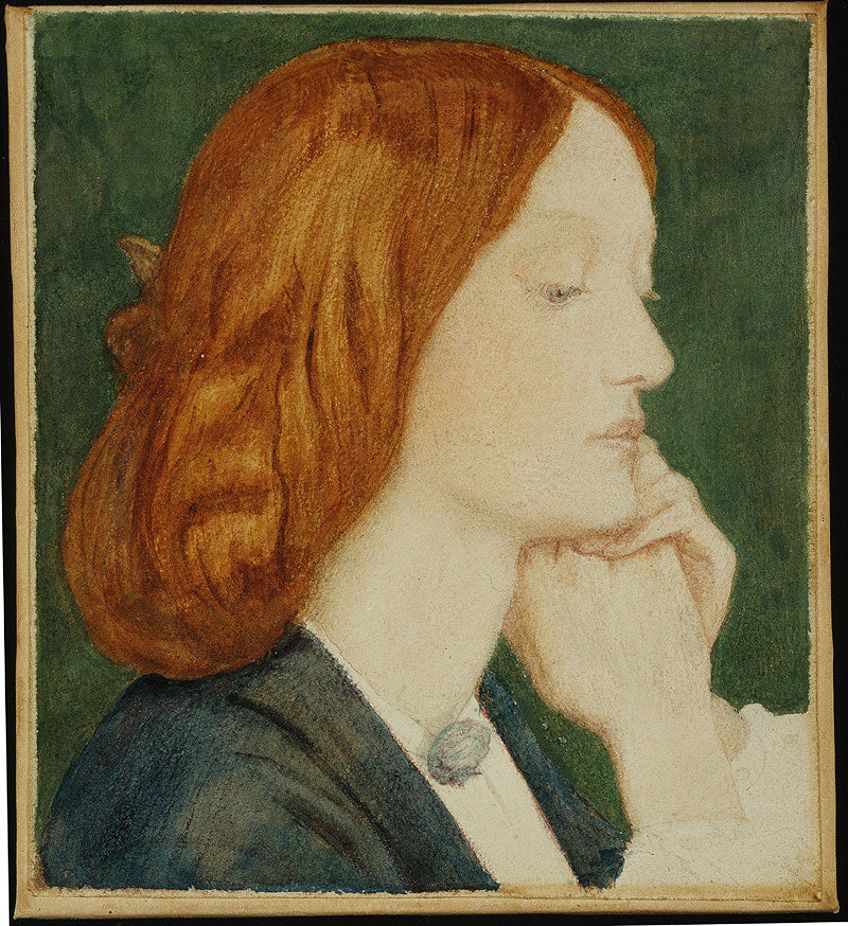

The model for this painting was none other than Elizabeth Siddal, beloved muse and wife of Dante Rossetti. She posed as the subject in many paintings created by members of the brotherhood, such as Millais and Hunt. An artist and poet in her own right, Siddal was a drug addict who tragically died from an opioid overdose at the tender age of 32 – a fate that eerily resembled the untimely death of Ophelia in Hamlet.

To provide a posture that served as a useful model for Millais to paint an accurate representation of Ophelia’s body floating in the water, Siddal lay in a bathtub of water that was kept warm with oil lamps. During this time, she contracted pneumonia and Millais paid for the doctor’s bills at Siddal’s father’s request. Millais also bought the dress for Siddal to wear when she was posing.

This painting is kept at the Tate Museum in London.

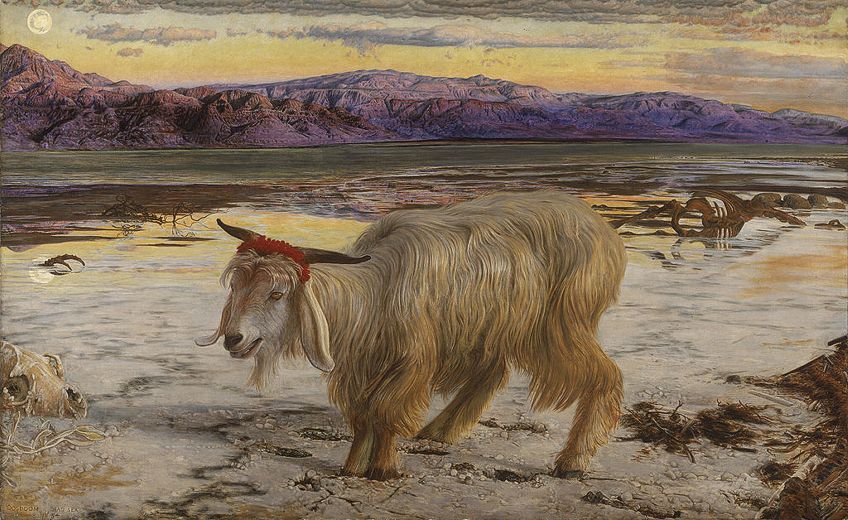

The Scapegoat (1854 – 1856) by William Holman Hunt

A classic Pre-Raphaelite painter, Hunt drew the subject matter of this painting from religious themes, which was a typical practice during the Renaissance era. The striking colors and highly realistic images in this captivating painting capture a story from Leviticus (a book in the Bible). It depicts Hunt’s Jewish tradition in which a sacrificial goat was sent into the desert once a year to symbolically carry with it the sins of society. In the painting, the horns of the goat are adorned with a red cloth that represents the crown of thorns around the head of Christ.

It was painted by William Holman Hunt, a Christian, after journeying through the middle east. His travels enabled him to obtain the most accurate depiction of the religious landscape possible, on the banks of the Dead Sea. He used rare, live goats that he bought himself – the first did not serve as an easy model, and eventually died while the painting was still in production, so Hunt was forced to purchase a second so that he could complete the painting. The artwork included an ornate gold frame which Hunt designed himself, which he said was imperative to understanding the painting as it included religious symbols and inscriptions.

It is currently being exhibited at the Lady Lever Museum in Liverpool in the UK.

Ecce Ancilla Domini (1849 – 1850) by Dante Rossetti

This painting was one of Rossetti’s most famous and also one of his most harshly criticized paintings, which was pivotal in causing the artist’s reluctance to continue painting religious scenes. As a result of it being unpopular in the public eye, it did not sell well when it was first exhibited in 1850 and was eventually bought by one of the brotherhood’s supporters.

This particular painting was one of Rossetti’s earliest works, depicting the Annunciation – the crucial moment in religious history when the angel Gabriel visits the Virgin Mary to deliver news of her unexpected pregnancy. The white lilies are a relic of Renaissance and medieval art, which were commonly used to symbolize purity. The haloes around both figures’ heads reveal the presence of divinity, despite their plain attire. The Latin title refers to the scene in the Gospel of St. Luke, and is translated as “behold the handmaiden of the Lord”.

Several people were models for this painting, including Rossetti’s brother and sister as well as professional models. It was inspired by the work of Eyck and Memling, which he saw in Bruges when he was on tour in Europe. He followed both their style and technique in the creation of this painting.

It is not the subject matter that was under scrutiny in Ecce Ancilla Domini, but rather how the scene was portrayed. Instead of being the vision of humility immersed in study, as she is more often shown, the virgin Mary is shown in this painting as a frightened girl in crumpled clothes rising from her bed as she is approached by the form of Gabriel. This depiction of the angel was another of many aspects of this painting that was criticized, referring specifically to his human-like appearance.

You can find this painting exhibited at the Tate Britain in London.

The Second Generation

Although the life of the brotherhood was short-lived, lasting only until the first few years of the 1850s, it was revived a couple of years later when a few students, along with some notable artists in the movement, combined forces to paint a mural in the Oxford Union Debating Hall. At around the same time, big names such as Burne-Jones, Rossetti, and Ruskin lectured art classes to working-class men. With the occurrence of these events, the passion of pre-Raphaelite artwork was destined to be reignited.

The resurfacing of the movement in this way culminated in the formation of a firm in 1961 called Morris & Co., which was established by several creatives such as Ford Madox Brown, Philip Webb, Louis Morris, Burne-Jones, and Rossetti. Morris & Co. was a company that was focused on producing decorative arts that, in contrast to the methods and products of industrialization, used older artistic approaches that allowed the natural beauty of the materials that were used, to shine.

This triggered what would become known as the “Art and Crafts Movement”, a larger-scale movement that took place between about 1860 and 1900 toward functional, decorative arts that was more accessible than the carefully curated world of galleries and museums.

The Arts and Crafts Movement

Although the Arts and Crafts Movement had a deep resonance with Pre-Raphaelitism, it differed from the latter and was perhaps even more consistent with the beliefs that underpinned the movement in the sense that it allowed its underlying tenets to express themselves in the form of artwork that was more functional than painting and sculpture, which made it more accessible to a wider variety of people. Types of artwork included tapestries and furniture that were simultaneously useful and aesthetically pleasing in the context of the household.

In producing functional items such as these, the mundane was brought to life by using nature as a template, and by drawing upon medieval and gothic art. A new possibility was emerging for art to become part of the everyday life of the everyday man, rather than being tethered to the walls of stuffy museums. In this way, people could experience their right to fulfillment and have the constant presence of beauty, creativity, and spirit in their lives.

This was the statement made to the industrial revolution, which created a place for heart in the life of the everyday man who was being drawn into the dull world of the machine at a pace unsurpassed in the history of humanity.

The manifestation of Pre-Raphaelite ideals within the Arts and Crafts Movement was not confined to the UK or European borders, or indeed to the 19th century. It made its way to the US and continued to add a spark to the art world until as late as the 1920s, directly influencing various art movements. Each of these movements developed its unique signature and brand but was also intimately influenced by the values of the Arts and Crafts Movement and the methods and materials used to convey a deep sympathy for pre-industrial methods.

The Wiener Werkstatte (1903 – 1928) was one such movement, which involved a collaboration between numerous architects, designers, and artists of the time who worked together to produce clothes, jewelry, furniture, and design that were all hand-crafted.

Closely tied to this was Art Nouveau (1890 – 1910), a relatively short-lived movement that was similarly inclined to create its style in decorative art, illustrations, building, and interior design, as well as posters and glass art.The Prairie School (roughly 1900 to 1950), an American form of design influenced by the Arts and Crafts Movement, also emerged and developed a distinct style of architecture.

The Sisterhood

For many years, the brotherhood was famously known for its rebellious, boisterous character, but in recent years the brotherhood has gained attention from another angle. Although it has been clear that women featured predominantly in the art that was created by members of this secret society, the fundamental role of women in contributing to the movement has more recently entered into the limelight.

Women who were inspired by this movement, and indeed who formed an integral part of it included Effie Millais, Elizabeth Siddal, and Christina Rossetti. They were the wives, muses, and lovers of three of the most predominant figures in the movement, but others posed as their models as well, while being avid artists and poets themselves, such as Evelyn de Morgan and Marie Spartali Stillman.

Examples of work from the sisterhood include Joanna Mary Boyce’s Elgiva, and De Morgan’s The Garden of Opportunity. For women such as Siddal, their modeling work provided a financial gateway that enabled them to devote their lives to their creative work.

The Pre-Raphaelite art movement captured the essence of a time in British history that was undergoing the social unrest associated with large-scale industrialization sweeping through the country. This was channeled into exquisite artforms that not only did justice to uninhibited expression of emotional reflections of taboo topics and human experiences in Victorian society, but which also brought art into the lives of ordinary people. Despite, or perhaps because of, the courageous statement made in the name of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, its influence reached far and wide even though it comprised of a relatively small group of members.

Take a look at our Pre-Raphaelite webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Were They Called the Pre-Raphaelites?

The name alludes to the period in art that came before Raphael – namely, the Italian Renaissance and Medieval Art. It was this art that the artists of the brotherhood believed had not yet been corrupted by rigid academic rules preventing true feeling and self-expression.

When Was the Pre-Raphaelite Period?

This art movement took place in the Victorian Era, where Pre-Raphaelitism began in the mid-1800s. Although it only lasted for a few years, there was a second wave in the 1950s that took form in the Arts and Crafts Movement. It had a strong influence on the development of succeeding art styles such as Art Nouveau into the early 20th century.

What Were the Pre-Raphaelites Rebelling Against?

The main focus of this group of artists was to challenge the artistic norms that were imposed by the Royal Academy of London, which were seen as an abomination to and repression of the pure art that reflected the true qualities of the subjects in the paintings. Their work also reflected topics that often brought to light uncomfortable aspects of human existence, such as death and infidelity, and their methods challenged the ideas inherent in the age of industry. Their work spawned the Arts and Crafts Movement, which set into motion the creation of decorative and functional artwork that was available to a broader spectrum of people.

What Was the Aim of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood?

In essence, the brotherhood was created to return to the purer form of art that they thought was embodied by the style of art from the Italian Renaissance and Medieval periods. This was achieved by bringing to life methods that were characteristic of those times. The primary aim was to create a superior form of art that was being taught by the Royal Academy of London that was more sincere and true to nature than conventional Victorian art.

What Does Pre-Raphaelite Mean?

This term refers to the time before Raphael. In the context of the art movement, it was the name of a secret group of artists in the Victorian era who challenged the values proposed by the mainstream art of the time, as it was taught by the Royal Academy. The term refers to the style, methods, and values of Medieval and Renaissance art.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Pre-Raphaelite Art – A History of the Pre-Raphaelitism Art Period.” Art in Context. May 10, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/pre-raphaelite-art/