Art Nouveau – The Decorative Stylings of the Art Nouveau Movement

What is Art Nouveau? The Art Nouveau movement explored a decorative art form that thrived in the United States and Europe from around 1890. The Art Nouveau style, which was popularly applied in interior design, architecture, jewelry and glass designs, advertising, and graphics, is distinguished by the employment of long, serpentine, natural lines. The Art Nouveau period was defined by a conscious effort to develop a unique design that was distinct from the mimetic classicism that characterized most 19th-century design and art.

Table of Contents

- 1 Exploring the Art Nouveau Style

- 2 Key Aspects of the Art Nouveau Movement

- 3 Examples of Art Nouveau Architecture and Art Nouveau Paintings

- 3.1 Cover Design for Wren’s City Churches (1883) by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo

- 3.2 Moulin Rouge: La Goulue (1891) by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

- 3.3 The Peacock Skirt (1892) by Aubrey Beardsley

- 3.4 The Budapest Museum of Applied Arts (1896) by Ödön Lechner

- 3.5 The Entrances to the Paris Metro (1900) by Hector Guimard

- 3.6 Ernst-Ludwig Haus (1901) by Joseph Maria Olbrich

- 3.7 Model #342, Wisteria Lamp (1905) by Clara Driscoll

- 3.8 Hope, II (1908) by Gustav Klimt

- 3.9 Park Güell (1914) by Antoni Gaudí

- 4 Art Nouveau Artists

- 5 Frequently Asked Questions

Exploring the Art Nouveau Style

Throughout Europe and far beyond, Art Nouveau designs and concepts generated a desire for decorative arts, architectural design, and style. As a consequence, it has a number of different aliases, including Jugendstil and the Glasgow style. By rejecting the formerly trendy diverse blend of earlier styles, Art Nouveau artists aspired to modernize the design.

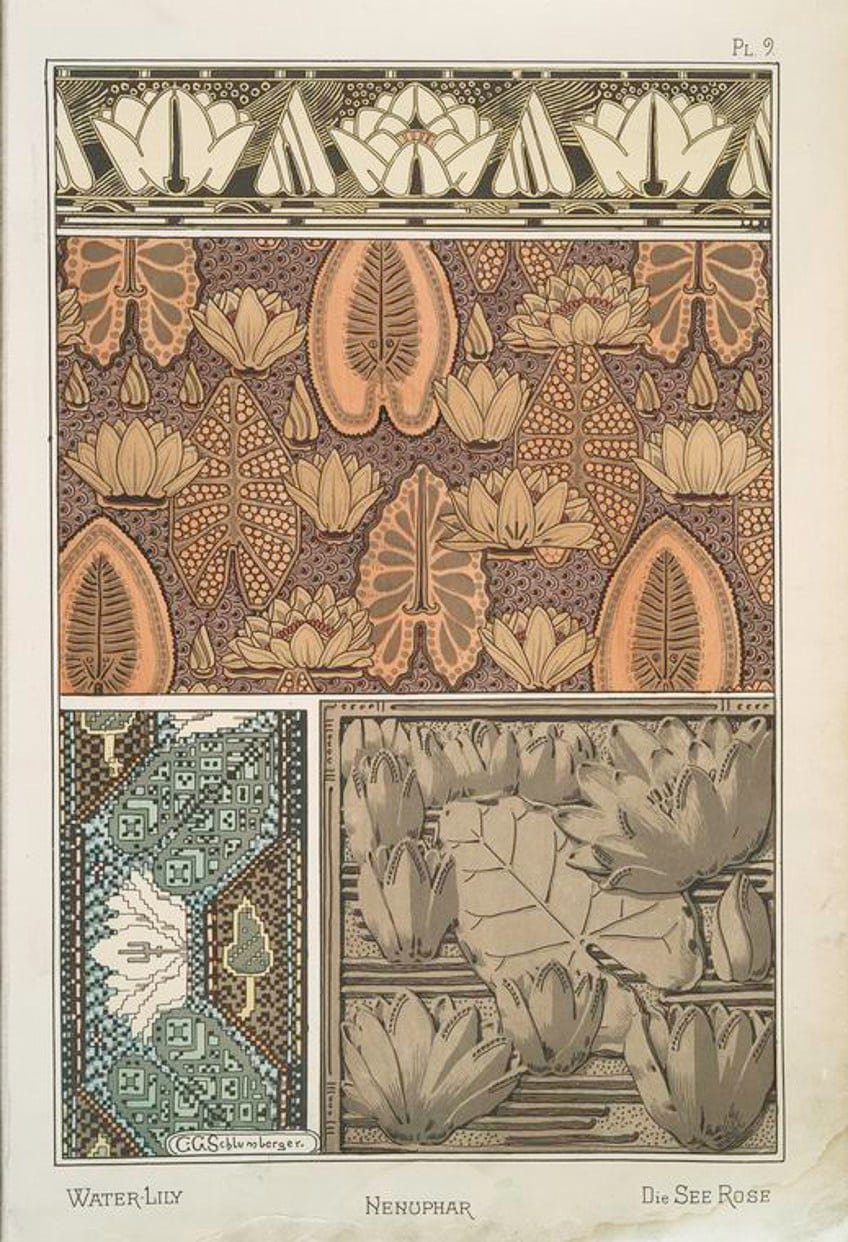

Art Nouveau patterns were inspired by naturalistic and geometric patterns and produced appealing designs that merged fluid, organic shapes suggestive of plant branches and flowers.

As a result, linear outlines took precedence over vivid colors like oranges, reds, and yellowish-orange. The Art Nouveau movement attempted to eliminate classical art systems, such as sculpture and painting being more essential than craft-based decorative arts. This design, which had fallen out of favor long before World War I, laid the stage for art deco’s revival in the 1920s. However, it was revitalized in the 1960s and is today seen as a key predecessor to, if not a core component of, Modernism.

The most prevalent examples of the style can be observed in Art Nouveau architecture and Art Nouveau paintings.

Important Concepts

The desire of Art Nouveau artists to break away from 19th-century historic traditions was a primary driving reason behind the Art Nouveau movement’s modernism. Despite the fact that industrialized manufacturing had become commonplace, imitations of earlier eras gradually became more prevalent in decorative arts.

Art Nouveau practitioners wanted to restore outstanding workmanship, enhance craft, and produce really modern designs that appealed to the pragmatism of the products they were creating and producing.

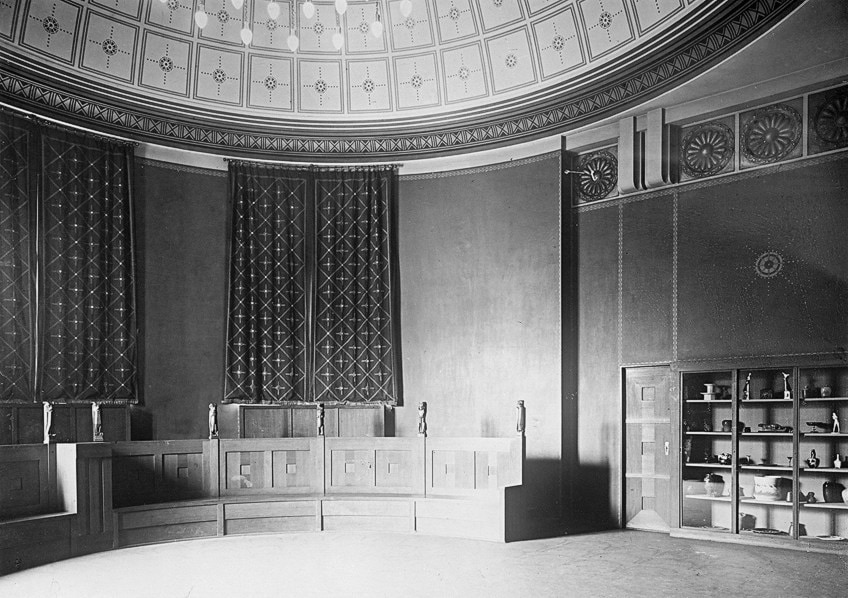

Due to the academic systems that characterized art training from the 17th through the 19th centuries, sculpture and painting were deemed preferable to skills like interior designing and ironwork. According to many, this resulted in disdain for excellent craftsmanship. When it comes to architecture and interior design, Art Nouveau architecture attempted to defy convention by constructing “complete works of the arts”, in which all of the parts worked in unison within a unified aesthetic language.

The Art Nouveau period was crucial in bridging the gap between the fine and practical arts, but it’s uncertain if that gap has ever been totally overcome. A number of Art Nouveau designers considered that previous designs were excessively ornamental to avoid what they viewed as unnecessary embellishment. This led them to feel that an object’s purpose, instead of the other way around, should affect its form.

In reality, this was an open-ended mindset that would affect future modernist movements, particularly the Bauhaus.

Key Aspects of the Art Nouveau Movement

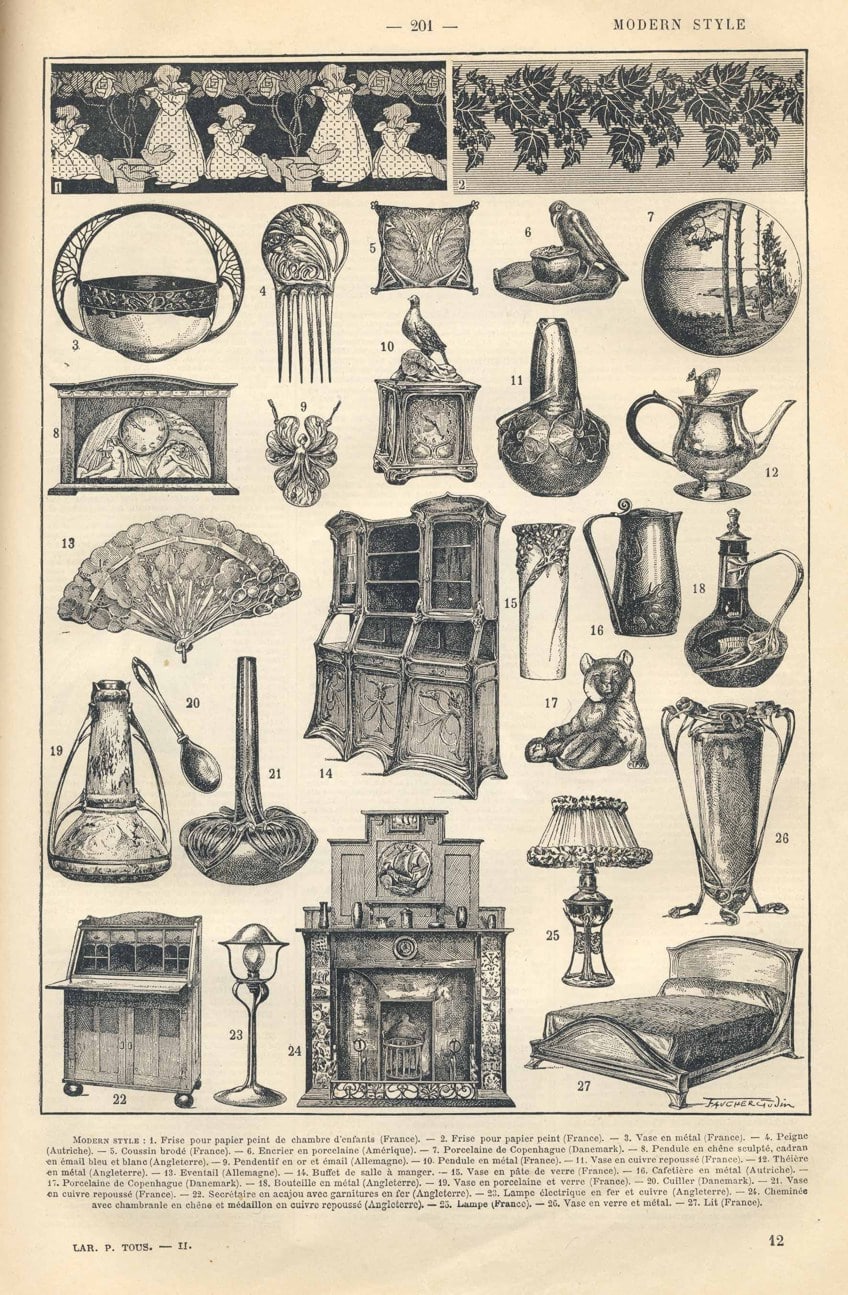

Around 1880, the Art Nouveau style arose as a reaction to the cluttered motifs and compositions of Victorian-era artwork. The second influence was the Arts and Crafts movement from England, which was a reaction against Victorian-era ornamental art, similar to Art Nouveau patterns. As a consequence, many European artists of the 1880s, such as Émile Gallé, Gustav Klimt, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler were captivated by Japanese artwork, particularly.

Flowery and globular designs, as well as “whiplash” curvature, were common in Japanese prints, which ultimately became linked with Art Nouveau designs. It’s difficult to tell which work or pieces of art officially launched Art Nouveau.

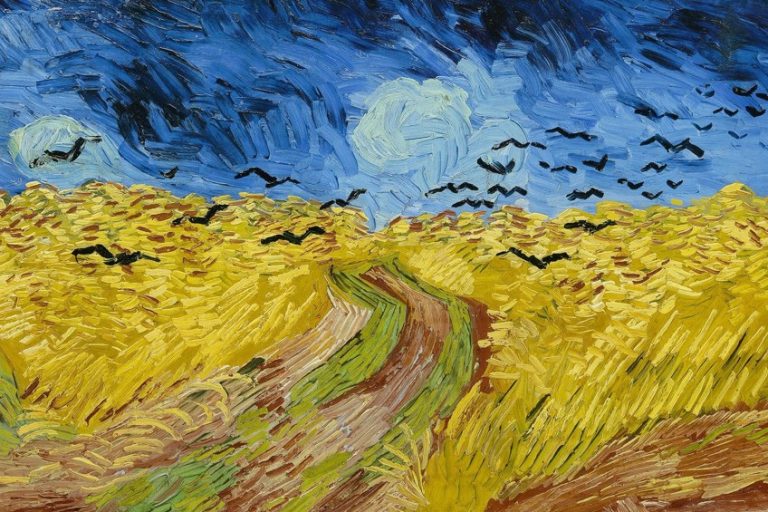

While some argue that Vincent van Gogh’s rhythmic, fluid lines and flowery backdrops mark the beginning of the Art Nouveau period, others argue that Henri de Toulouse-ornate Lautrec’s lithographs demonstrate the culmination of the style.

Exhibitions

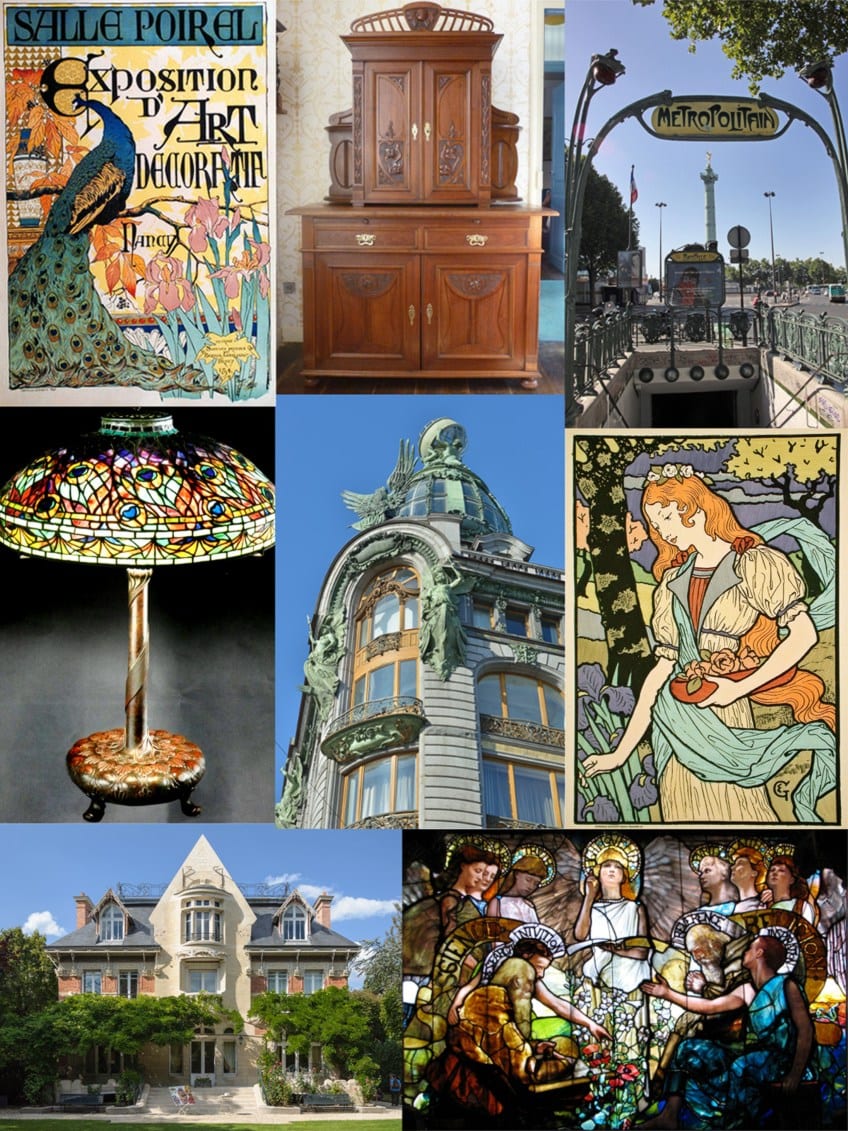

Art Nouveau paintings and architecture were most prominent in international exhibits during its heyday. The Tervueren Exhibition in Brussels, The Paris Universal Exhibition of 1889, and the Nancy International Exposition of 1909 all exhibited it significantly (where Art Nouveau design was mainly utilized to demonstrate the potential of workmanship with exotic timbers from the Belgian Congo).

Each of these exhibitions was centered around decorative arts and architecture, and eventually Art Nouveau was actually the trend of choice for nearly every architect and country exhibited, with no other styles jockeying for position or sales.

L’Art Nouveau, founded in 1895 by Siegfried Bing, a German trader who was also an admirer of Japanese art, became a major supplier of the style’s decorative arts and furniture. The store’s fame extended across Europe and the United States, and it became a household name. Art Nouveau has been called a multitude of titles due to its extensive popularity in Western and Central Europe. In German-speaking countries, it was dubbed Jugendstil when a Munich journal called Jugend popularized it.

The name “Sezessionsstil” was coined in Vienna, home of artists such as Otto Wagner, Gustav Klimt, and Josef Hoffmann, all members of the Secession Style.

Art Nouveau Design Concepts

The great appeal of the Art Nouveau period in the late 19th century can be ascribed in part to the use of easily reproduced graphic art forms by many artists. During the Jugendstil era, print media such as book covers and exhibit catalog covers, magazine advertisements, ticket stubs, and billboards were fashionable in Germany.

However, this new growth was not only limited to the German-speaking globe.

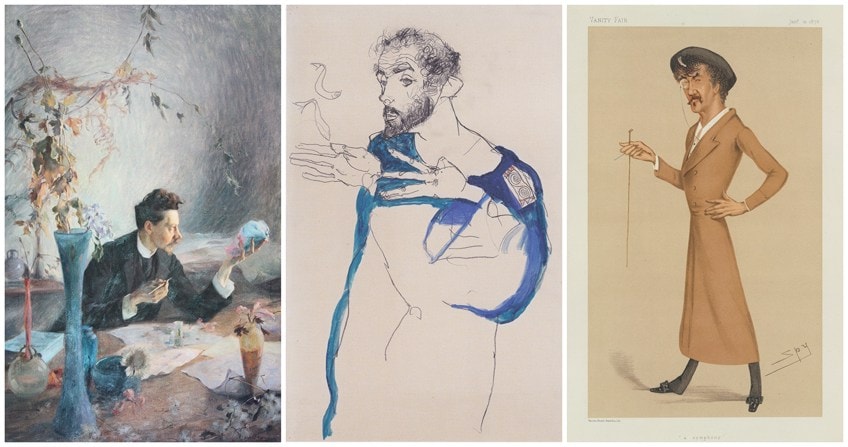

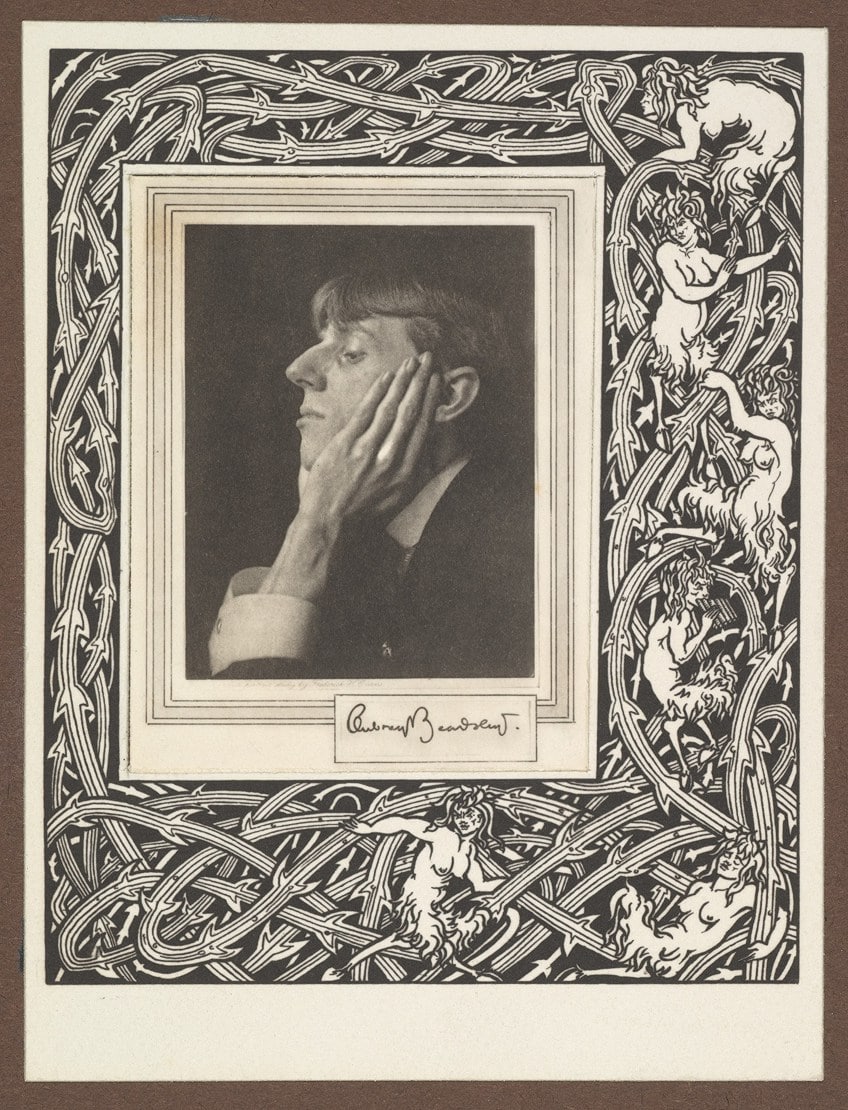

In his brief career, Aubrey Beardsley, a British artist noted for blending the erotic and macabre in his work, created a series of posters with flowing, rhythmic lines. Because of his art, he was one of the most divisive individuals in Art Nouveau. Beardsley’s highly embellished works show that Art Nouveau and Japonism prints have much in common.

New chromolithographic processes were used to promote new technology like electric lights and telephones, as well as nightlife venues such as taverns and eateries, and even solo performances, all of which conveyed the thrill and energy of modern living. As a result, the poster was quickly elevated from a banal form of advertisement to a work of art. Any genuine study of Art Nouveau must include architecture and its huge impact on European culture.

Art Nouveau blossomed architecturally in large cities such as Brussels and Paris, as well as smaller towns such as Darmstadt, and Eastern European localities such as Prague, Riga, and Budapest.

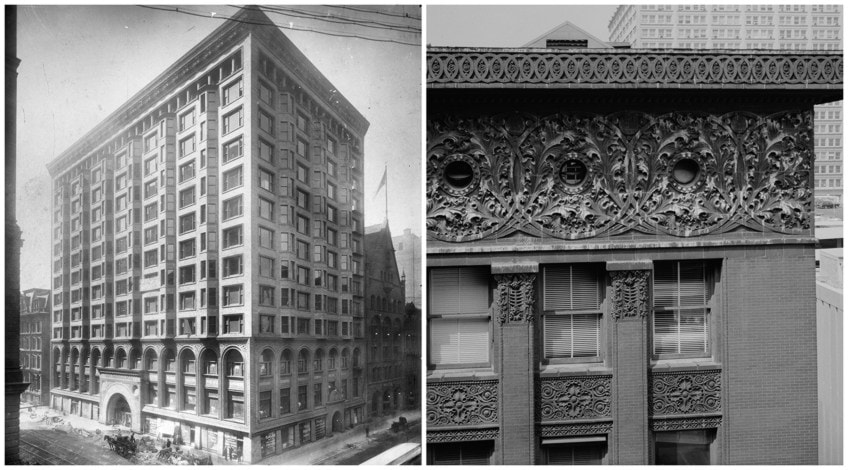

Art Nouveau Architecture

It may be found in anything from modest row dwellings to large institutional and commercial structures today. Art Nouveau occurred in a wide range of architectural styles, most notably. Many structures make considerable use of terracotta and colorful tilework. Alexandre Bigot, for example, became famous in the late 19th century for his terracotta decorations for the exteriors and fireplaces of mansions and apartment complexes in Paris.

Iron buildings are connected by glass panels in many other Art Nouveau buildings, notably in Belgium and France. In many regions of Europe, Art Nouveau architecture was popular, using local materials such as yellow limestone coupled with wood trim. In many cases, sculptural white stucco coverings were used, particularly on Art Nouveau exhibition pavilions.

The Chicago Stock Exchange and Wainwright Building are two of Louis Sullivan’s buildings that are regarded among the finest examples of Art Nouveau architecture in North America.

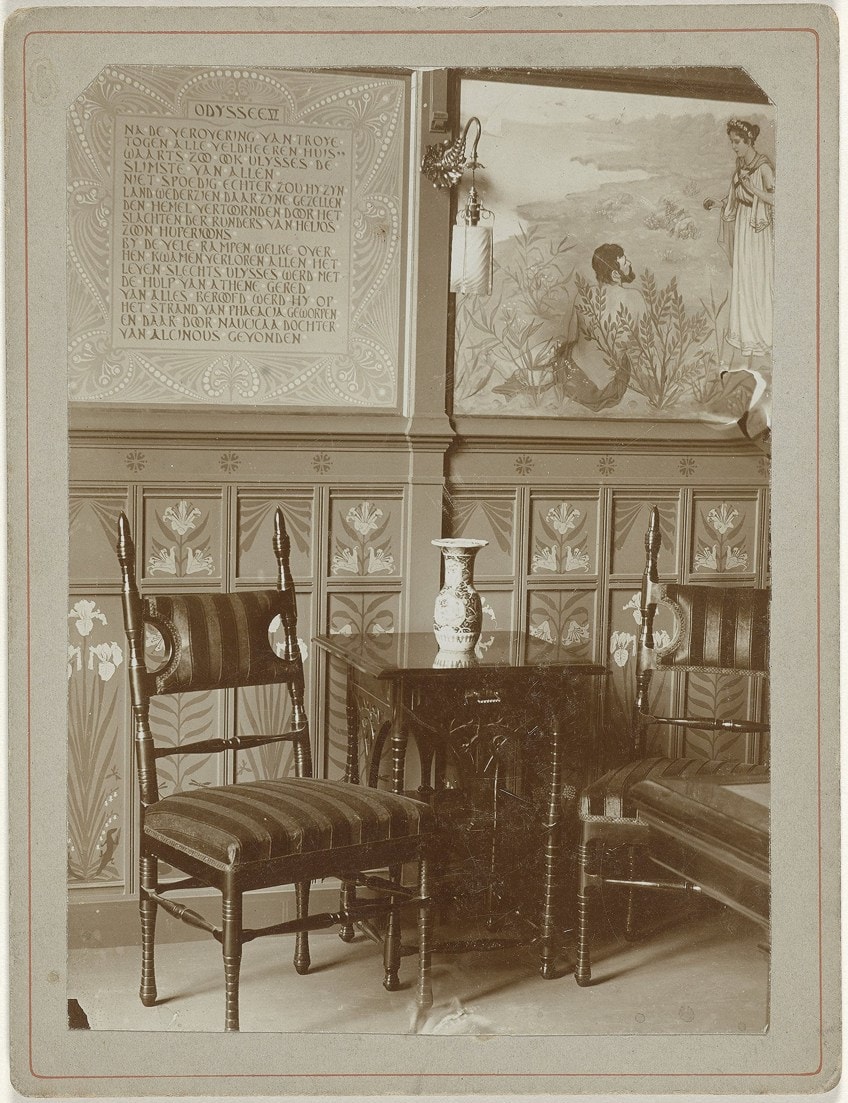

Interior Design

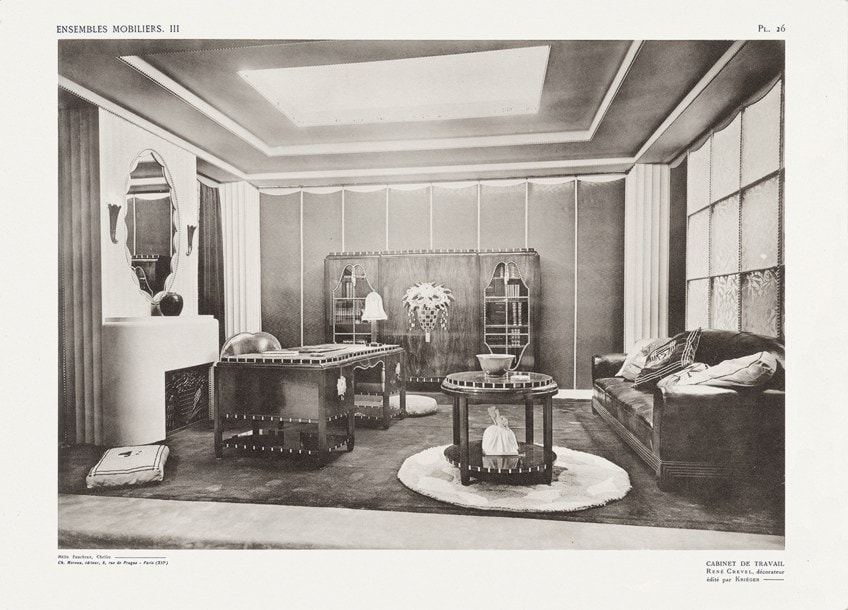

Art Nouveau design, like the Arts and Crafts traditions before it, was concerned with both interior and exterior design. Art Nouveau interiors strove to create a coherent environment that made the most of every square inch. In this context, much emphasis was focused on furniture design, particularly in the manufacturing of hand-carved wood with sharp, irregular curves, which was normally done by artisans but occasionally by machines.

Furniture producers made beds, dining room chairs and tables, sideboards, and lampstands. The flowing curves of the patterns, which were used as wall paneling and crown molding, were inspired by the natural grain of the wood.

The most well-known French Art Nouveau designers were Emile Gallé, Eugène Vallin, Tony Selmersheim, and Louis Majorelle. The whiplash lines and restricted, more angular shapes were utilized by Belgian artists Henry van de Velde and Gustave Serrurier-Bovy who were both inspired by the Arts and Crafts style.

The Italians Augustino Lauro and Alberto Bugatti were among the most well-known guests to the nation.

Majorelle, who produced in a number of mediums, was infamous for being difficult to categorize. He developed and manufactured his own furniture pieces, for instance, before opening an ironworking foundry and producing metal fittings for the Daum Brothers’ glassworks.

Art Nouveau Paintings

Art Nouveau is one of the only styles whose work may be found in almost any visual or material media. Famous artists associated with Art Nouveau include Gustav Klim, and Victor Prouvé, a French graphic designer who specialized in design, graphics, and architectural work.

Artwork from the period is hard to come across due to the paucity of Art Nouveau artists like Klimt and Prouvé, who was both an architect and an artist.

Art Nouveau artists may have done more than any other time in history to bridge the gap between ornamental and applied arts, which had previously been seen as more significant and pure representations of creative talent and expertise. However, whether or not that chasm has ever been closed is debatable.

Jewelry and Glasswork

Art Nouveau’s penchant for luxury was used by some of history’s most well-known glassmakers. Emile Gallé, Jacques Gruber, and the Daum Brothers were all famed for their Art Nouveau glass, which was employed in a broad range of utilitarian goods throughout their professions. These companies made their reputations in vase design and art glass, respectively, by pioneering novel ways in acid-etched pieces with sinuously curving, shapely patterns that looked to flow between translucent colors with ease.

Furthermore, glass painters such as the Daum Brothers utilized it to make practical goods such as shades, vases, and desk decorations.

Jacques Gruber and Tiffany, both of whom had trained with the Daum Brothers, were masters of large-scale luminant paneling with stained glass reflecting nature’s splendor. Louis Comfort Tiffany, René Lalique, and Marcel Wolfers were among the notable jewelers of the time.

Despite the notion that its accessibility would make it more readily available, they manufactured it all from rings and pendants to necklaces and pins, guaranteeing that Art Nouveau would stay associated with luxury.

Corporate and Retailing Identity

Shopping was growing to attract a larger clientele at the same time that Art Nouveau was gaining popularity. It was widely displayed in the late 19th century at the La Samaritaine, and Wertheim’s. There were some major design businesses that championed the style, such as Siegfried Bing’s L’Art Nouveau Boutique in Paris, which remained a bastion of the movement until 1905, only a few years after Bing’s passing.

Not only was his business selling Art Nouveau interiors and furnishings, but so were others across the city. Liberty & Co. was the movement’s primary Italian and British distributor, and consequently, Liberty’s brand grew closely associated with the movement.

Numerous Art Nouveau designers rose to prominence after working exclusively for these establishments.

Designers such as Peter Behrens designed everything from kettles to book illustrations, exhibit pavilion furnishings, kitchenware, and furniture, eventually becoming the first industrial designer when AEG hired him to oversee all design work in 1907.

After the Art Nouveau Period

In the last half-decade of the 19th century, as in the first ten years of the 20th century, architects, artists, and designers changed their stance and public outlook on the Art Nouveau style. Some designers thought that “form must follow function,” but others went far with embellishment, and the style was criticized for being too excessive. As the period continued, a growing number of critics claimed that rather than rejuvenating design, the new style just replaced the previous with something that appeared to be new.

Even with new mass-production processes, the high degree of expertise demanded by most Art Nouveau designs ensured that it would never be as accessible to the general population as its supporters had hoped.

Due to lax international copyright restrictions, several artists in Darmstadt were unable to earn monetarily from their works. The relationship between the Art Nouveau movement and exhibitions was doomed from the outset. To start with, the bulk of the fair’s buildings were only intended to be transitory and were promptly removed after the celebration was over.

While well-intentioned, the exhibitions themselves served to foster rivalry and competition among countries due to the naturally comparative character of exhibitions, rather than promoting education, intercultural cooperation, and peace.

Art Nouveau was considered a candidate for the title of “national style” in a number of nations, including Belgium and France until charges of its foreign roots or subversive political overtones turned popular sentiment against it. By 1910, Art Nouveau had all but vanished from Europe’s design landscape, with just a few notable exceptions where it had a devoted local following.

The Death of Art Nouveau

Early in 1903, designers like Josef Hoffmann, Peter Behrens, and Koloman Moser in Austria and Germany began to move away from Art Nouveau in favor of a more sparse, strictly geometric style. In the same year, a group of designers formerly linked with the Vienna Secession formed the Wiener Werkstätte, whose penchant for sharply angular and rectilinear shapes recalled a more accurate, industrially-inspired style devoid of overt connections to nature.

Both Behrens’ appointment as chief designer of AEG, establishing him as the planet’s very first industrial designer, and the establishment of the German Werkbund in 1907, emphasized this conceptual framework of the machine-made characteristics of the design.

This machine-inspired style would grow into the aesthetic that we now call Art Deco in the aftermath of World War I.

Influences

Despite its brief existence, Art Nouveau had a considerable influence on graphic designers from the 1960s to the 1970s who sought to break away from the stark, cold, and more minimalist design that had previously dominated the industry.

Art Nouveau influenced artists like Peter Max to produce work that portrays the innovative, ephemeral, and free-flowing creative world of the early 20th century in its dreamlike, psychedelic sensory experience.

Art Nouveau was recognized as an important stride toward modernism in architecture and art from the start. It is now seen as a reflection of the manner, atmosphere, and intellectual thought of a specific historical time centered around 1900.

It became the visual medium that characterized the modern era’s desire for a truly current style for a limited period of time.

Examples of Art Nouveau Architecture and Art Nouveau Paintings

So far, we have covered the key concepts of the Art Nouveau style, as well as the history of the Art nouveau movement. Now we will look at some distinctive examples of Art Nouveau paintings and architecture. We can see how these Art Nouveau designs have influenced every form of art.

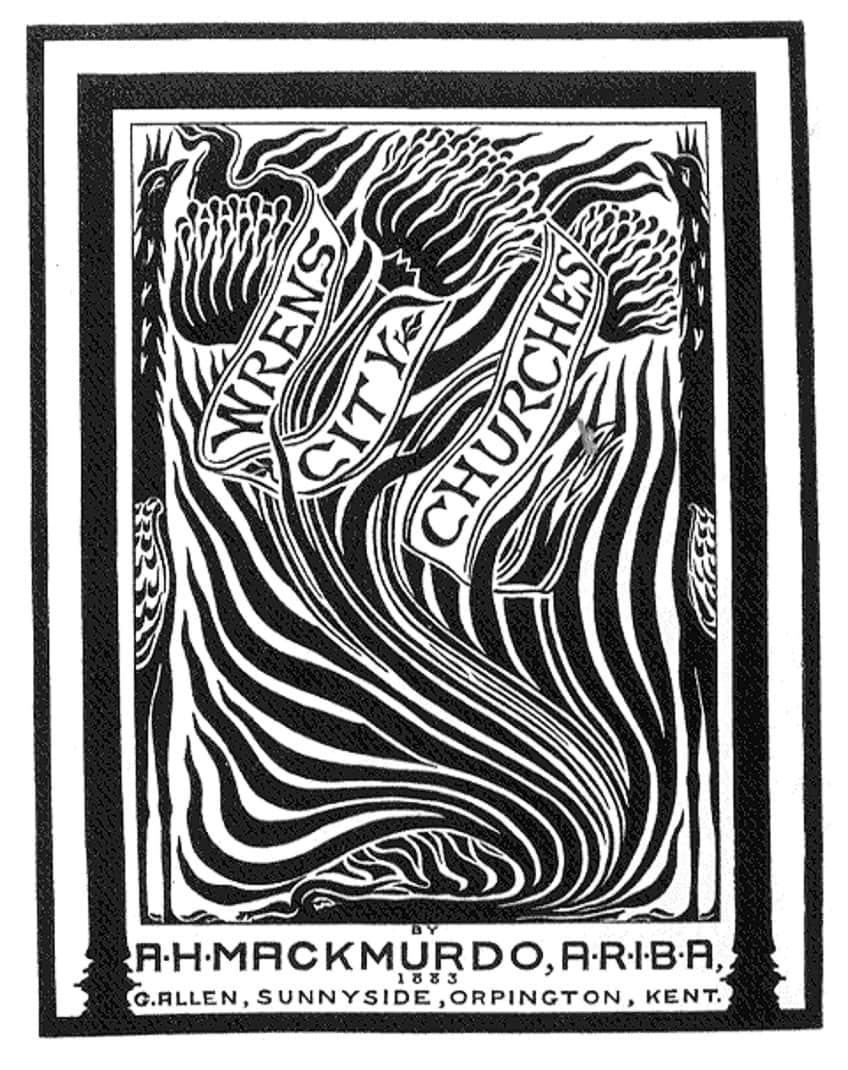

Cover Design for Wren’s City Churches (1883) by Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo

| Date Completed | 1883 |

| Medium | Woodcut on paper |

| Dimensions | 29 cm x 23 cm |

| Current Location | Multiple prints available |

Art Nouveau was influenced by the English Arts and Crafts movement, particularly the Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo woodcut. Two factors lend to this affiliation: the handcrafted character of the artwork, which identifies a woodcut, and Mackmurdo’s use of negative and positive space, which is simple.

Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo’s abstract-naturalistic forms, as well as his signature whiplash curves, exemplify the visual illusion of motion and vitality that would come to define Art Nouveau in the years ahead.

The book’s apparent subject matter is concealed by the concentration on floral and vegetal imagery on the cover, underlining the book’s purposefully decorative look and implying that Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo’s effort is exploratory rather than a fully formed instance of the Art Nouveau style.

The woodcut is far more valuable than the text, which is a scattershot account of London church architecture.

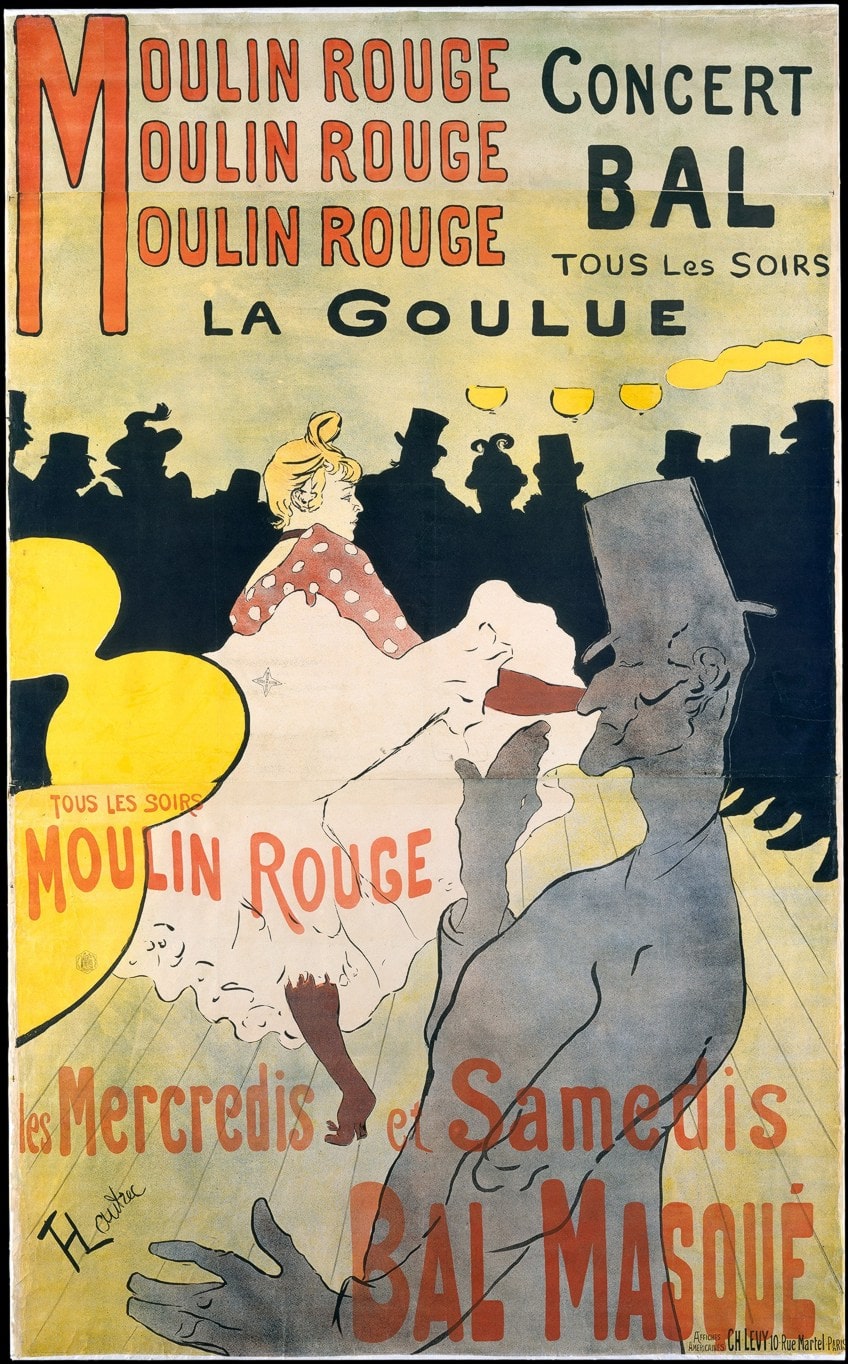

Moulin Rouge: La Goulue (1891) by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

| Date Completed | 1891 |

| Medium | Lithograph |

| Dimensions | 170 cm x 118 cm |

| Current Location | Philadelphia Museum of Art |

Toulouse-Lautrec, one of Art Nouveau’s most prominent graphic designers, elevated the billboard from an item of commercial junk to creation of fine art in the 1890s, the very same decade that saw the emergence of creative journals completely committed to this medium. Even though the word “Art Nouveau” was not introduced until after Lautrec’s death in 1901, the graphic designers who collaborated with him recognized their own inventiveness.

This design takes the flair and wildness of a French can-can dancer’s garment and reduces it to a few basic, rhythmic lines, implying motion and space.

The flattening of shapes to basic outlines with flat color infill reflects Art Nouveau’s affinity to Japanese prints as well as the illumination in such nightclubs, which would naturally render surface details of persons and other things obscure. Similarly, the cabaret’s name, written in red letters, indicates the throbbing intensity of the performances, in which dancers such as La Goulue took center stage.

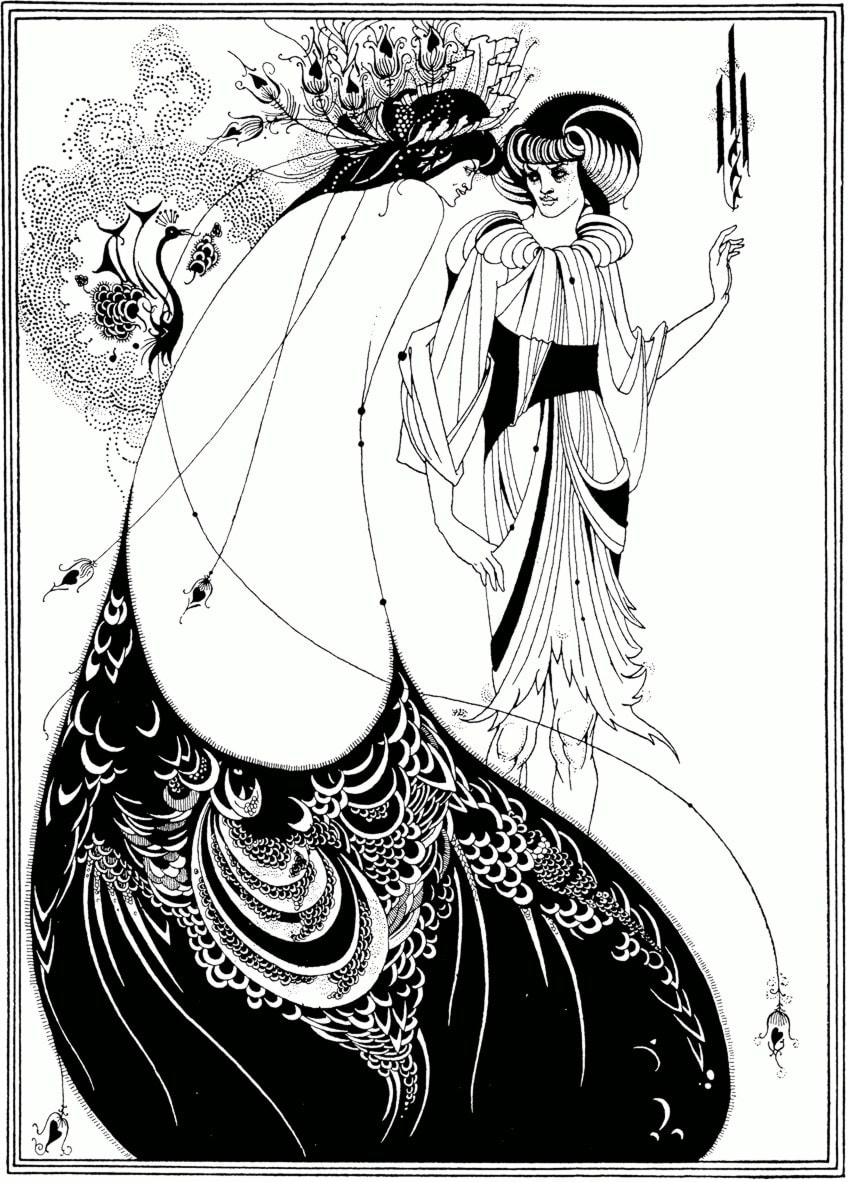

The Peacock Skirt (1892) by Aubrey Beardsley

| Date Completed | 1892 |

| Medium | Ink illustration |

| Dimensions | 17 cm x 12 cm |

| Current Location | Play billboard print |

This artwork was made as a picture for Oscar Wilde’s 1892 drama Salomé, which was based on the Biblical story of Salome ordering the head of John the Baptist to be decapitated and placed on a platter. Several other Art Nouveau painters, like Victor Prouvé, were inspired by Salome. Compared to some of Beardsley’s other more sensuous and downright nasty works, Salomé is a mild-mannered affair.

Several of the Art Nouveau-influenced artists emphasize line, and they commonly abstract their figures to obtain the Art Nouveau-inspired flowing curves.

It may also serve as an example of how passionate usage of the style’s formal vocabulary may lead to critique. Beardsley’s work demonstrates the influence of Japanese prints on Art Nouveau through its flattened portrayal of form. This image may also be viewed as a depiction of the modern Aesthetic movement, demonstrating how Art Nouveau was inspired by many historical eras and genres.

The Budapest Museum of Applied Arts (1896) by Ödön Lechner

| Architect | Ödön Lechner |

| Date Completed | 1896 |

| Function | Museum |

| Location | Budapest |

The Budapest Museum of Applied Arts, designed by Ödön Lechner, demonstrates how the Hungarian “national” branch of Art Nouveau, called the Hungarian Secession due to its location to Vienna, was more of a fusion of previous forms than a quest for new ones.

This structure, which sits on a trapezoidal lot, features an atrium at the back of the primary façade that is filled with natural daylight.

Tilework, stained-glass windows, and stone link the complicated structure all around, creating a vivid polychrome style that maintains the audience’s eye wandering and informs one of the harmonizing the union of art forms in generating a “complete work of art”. The complex multi-lobed arches, along with Central European-derived grandiose, bell-shaped spires and towers with onion-shaped sculpted finials, are examples of the forms utilized inside and out.

The Entrances to the Paris Metro (1900) by Hector Guimard

| Architect | Hector Guimard |

| Date Completed | 1900 |

| Function | Subway entrance |

| Location | Paris |

Following London, Paris was just the second city in the world to build an underground rail system when Hector Guimard was commissioned to design these renowned subway station entrances. Hector Guimard’s design was inspired by the aim to commemorate and promote the new infrastructure with a dramatic tower that would stand out in the Paris skyline.

The entrances feature Art Nouveau-style twisted, organic shapes that appear to be practically seamless at first glance, but are really made up of multiple cast iron components that could be mass-produced in Osne-le-Val, east of Paris.

Hector Guimard had effectively hidden some aspect of the object’s modernism behind its serpentine continuity, a method that typifies Art Nouveau’s ambiguous stance toward the modern period. Hector Guimard’s design was therefore critical in introducing Art Nouveau’s normally sophisticated, labor-intensive designs to a broad audience for whom the style was thought to represent unachievable luxury.

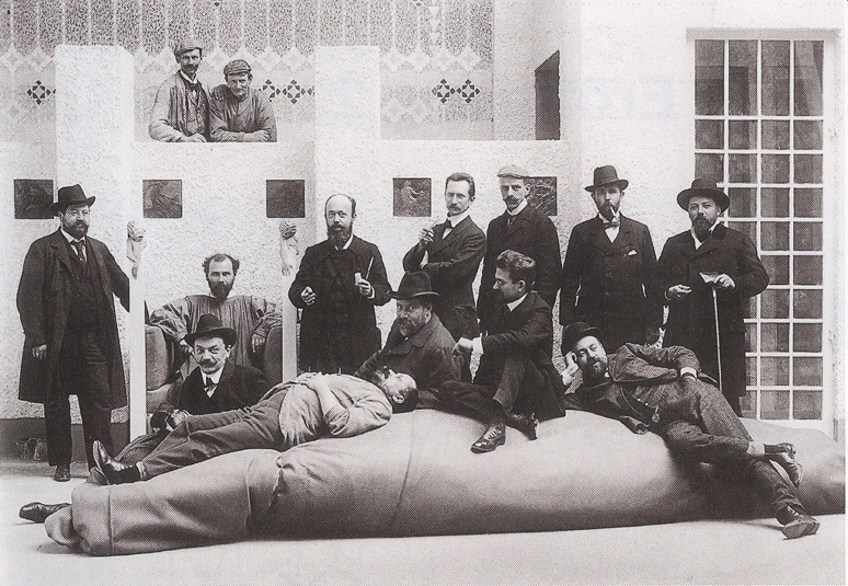

Ernst-Ludwig Haus (1901) by Joseph Maria Olbrich

| Architect | Joseph Maria Olbrich |

| Date Completed | 1901 |

| Function | Studio building |

| Location | Darmstadt, Germany |

This is the focal point of the new Darmstadt Artists Community, which was founded in 1899 under the auspices of Grand Duke of Hesse. Olbrich, who was among the community’s original painters, was stolen from the Vienna Secession by the Duke. The Ernst-Ludwig Haus, like Secession architecture, is highly rectilinear, with a shining white facade crowned by a gently sloping roof and situated on a hill.

The arched, centrally positioned main entrance, with its gold-plated, cloudlike geometric design around the entryway, which is flanked by Ludwig Habisch’s two male-and-female statues portraying the Strength and Beauty, counteracts this.

The sloping skylights that run the length of the back of the tower reveal its role as one of the few Art Nouveau structures constructed primarily for studio space, and it was the focal point of the Darmstadt group’s first exhibition in 1901. Despite the fact that the Colony only existed until the onset of World War I in 1914, the facility now functions as a museum dedicated to its artistic accomplishments.

Model #342, Wisteria Lamp (1905) by Clara Driscoll

| Date Completed | 1905 |

| Medium | Leaded glass and bronze |

| Dimensions | 70 cm x 45 cm |

| Current Location | New York Historical Society |

Louis Tiffany’s is well-known for their Art Nouveau table lamps. The leaded glass shade of the lamp seems to resemble the wisteria branches at its top when lighted. The bronze base and shade work together to give a natural appearance. The screens of nearly 2,000 painstakingly chosen pieces of glass provide a warm, but soft illumination, giving the blooming flowers the illusion of water drops pouring. This indicates that sunlight has passed through the screen.

This motif, which incorporates an irregularly-shaped framework at the top and a bottom boundary, mimics realism and Japonism, as wisteria is native to the eastern side of North America as well as Japan, China, and Korea.

Clara Driscoll designed it, according to newly unearthed evidence. It also marks a watershed event for female designers at the turn of the century, when they were given control of a large portion of the company’s manufacturing. Driscoll was among the highest-earning females of her period, earning $10,000 a year until she was forced to quit Tiffany Studios in 1909 when she got engaged and eventually married.

Hope, II (1908) by Gustav Klimt

| Date Completed | 1908 |

| Medium | Oil and gold leaf |

| Dimensions | 110 cm x 110 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Modern Art |

Gustav Klimt’s work is marked by form deformation and embellishment, as well as explicit sexual themes. Gustav Klimt, unlike Beardsley, is noted for his extensive use of gold leaf, usually in combination with a kaleidoscope of other vivid colors, particularly in his post-1900 works.

Gustav Klimt developed his unique sophisticated aesthetic as a consequence of this mixture.

This can be summarized as an array of dreamy, visually luscious (as well as materially lavish) paintings of women, occasionally portraying real people, but more often displaying envisaged or metaphorical embodiments, such as in his artwork Hope, II.

Gustav Klimt achieved his objective of producing a “new art” that was free of existing conventions or principles by employing accentuated and flattened body forms, as well as a focus on patterns and a lack of depth.

As original members of the organization, Secessionists like Klimt criticized academic painting’s ideals.

Gustav Klimt’s work evoked a wide spectrum of emotions during his lifetime and continues to do so now, contributing to his status as one of the most forward-thinking painters of the Art Movement and a pioneer of modernism.

Park Güell (1914) by Antoni Gaudí

| Architect | Antoni Gaudí |

| Date Completed | 1914 |

| Function | Park |

| Location | Barcelona |

Antoni Gaudí, best known for his work on the unfinished Sagrada Familia Expiatory Church in Barcelona, also built dozens of other structures in the Catalan metropolis. Antoni Gaudí’s final project before dedicating himself entirely to the Sagrada Familia was the preparation of a hillside residential neighborhood for textile entrepreneur Eusebi Güell.

Regardless of the fact that only Gaudi’s residence and one other property were built, and that the venture was a financial failure, this structure exemplifies Gaudí‘s innovative architectural skill.

Park Güell’s architectural style blends seamlessly with the surrounding environment, with rough-hewn slanted columns that appear to have been dug from the slopes and covered in vines. A columned market space supports an open plaza, which is surrounded by a serpentine seat covered with a combination of abandoned ceramic tiles known as trencads, a characteristic of Catalan artistry.

A great stairway connects the market to the park’s entrance, which has a tiled basin with a dragon’s face and the Catalan flag. The main gate and concierge’s apartment are made out of rocky lodges with uneven, conical spires that look as if they were made out of gingerbread.

The undulating shapes, influenced by inverted catenary arches, and vividly colored tilework reflect Catalan Art Nouveau’s collaborative ethos, comprising teams of artisans specialized in several media and dependence on the ethical management of environmentally sensitive materials.

Art Nouveau Artists

Now we have looked at some of the most famous examples of the Art Nouveau style. But who were the artists behind the movement? Let us discover some of these pioneers in the movement.

Émile Gallé (1846 – 1904)

| Nationality | French |

| Year of Birth | 1846 |

| Year of Death | 1904 |

| Medium | Glass maker |

Along with Louis Majorelle, Émile Gallé, a glassmaker, created the École de Nancy, an organization committed to extending the reach of Art Nouveau. He personally instructed the designers and supplied them with watercolors of floral patterns he created in his home’s gardens.

Gallé instructed his designers to utilize only genuine flowers and plants as models, albeit they were allowed to make certain creative choices in the end.

“It is vital to have a marked leaning in favor of models borrowed from flora and animals while allowing them free expression,” he wrote in 1889. Nature and literature both influenced his art. In his spare time, he would gather and study plants and bugs for inspiration, developing experimental glass-making processes that he ultimately trademarked.

Many of his works had flower patterns and poetry written just for the owner.

Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848 – 1933)

| Nationality | American |

| Year of Birth | 1848 |

| Year of Death | 1933 |

| Medium | Painting, glass making |

Louis Comfort Tiffany was the son of Charles Lewis Tiffany, a well-known jeweler. Though he was originally trained in painting, he started dabbling with stained glass in 1875, and three years later, he opened his own glass business.

His skill with glass became well-known in other countries.

Education, a stained-glass window at Yale University’s library, is his most well-known work. It was erected in honor of one of Yale’s sponsors’ daughters. The sculpture was taken from the premises in 1970 as a precautionary measure in case of demonstrations. As a result, it was mistaken and forgotten later on.

Years later, when the item was mislabeled and another Tiffany piece went missing instead, this blunder likely protected the piece from robbery.

Antoni Gaudí (1852 – 1926)

| Nationality | Catalan |

| Year of Birth | 1852 |

| Year of Death | 1926 |

| Medium | Architecture |

Antoni Gaudí was a pioneering architect who mostly worked in Barcelona, where his Art Nouveau style dominated. With flowing lines and bright surfaces that deviated from normal architectural forms, his work was influenced by nature and the Catholic religion.

The balconies of Casa Mila depict abstractions of leaves and blades of grass, while the benches in Parc Güell are supposed to line with the human spine. Gaudí was identified as an Art Nouveau member by his imagination, which set him apart from other styles of the time.

La Sagrada Família, his most renowned masterpiece, has been under development since 1882 and is continuously being worked on today.

Gaudí was assigned to commence on the church in 1883 despite the fact that he would not survive to see it finished, a reflection of his strong religion. The church was approximately 20% built when Gaudí died in 1926. When finished, the structure will be the world’s highest basilica.

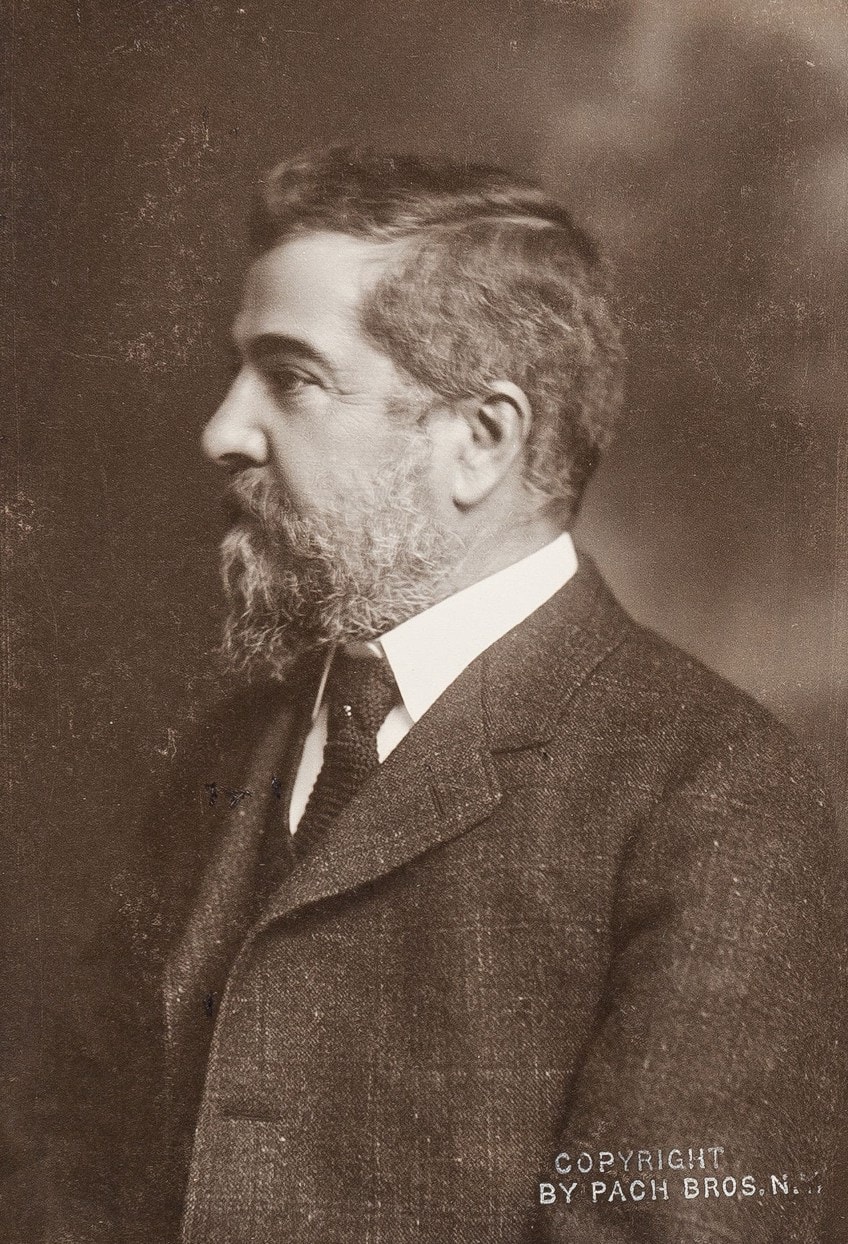

Victor Horta (1861 – 1947)

| Nationality | Belgian |

| Year of Birth | 1861 |

| Year of Death | 1947 |

| Medium | Architecture |

Victor Horta was a founding member of Art Nouveau and is credited for broadening the movement’s scope beyond the visual and ornamental arts to include building. Horta’s work was distinguished by his grasp of technological advancements in both iron and glass.

His structures were clad with twisted and bent iron that flowed from the exterior to the interior.

The Hôtel Tassel was the first Art Nouveau structure and one of Horta’s most well-known masterpieces. This townhouse was created for one of his Université Libre de Bruxelles colleagues. It perfectly blends natural and industrial motifs, and the building’s renowned stair hall can be seen from the outside.

The Art Nouveau movement started in 1890 with the purpose of updating the design and rejecting previously established classic and historical forms. Natural features such as flowers and insects inspired Art Nouveau painters. Curves, asymmetrical shapes, and vibrant colors were among the movement’s other recurring themes. In addition to ornamental art, painting, architecture, and even commercials, the Art Nouveau style appears in a variety of media.

Take a look at our Art Nouveau style webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Art Nouveau?

Many talented artists specialized in ornamental art, architectural design, and glass craft, particularly slag glass, emerged from the Art Nouveau movement. Collectors and Art Nouveau enthusiasts alike seek out much of their work nowadays. The desire of Art Nouveau artists to break away from 19th-century historic traditions was a primary driving reason behind the Art Nouveau movement’s modernism.

Where Does Art Nouveau Come From?

Art Nouveau may be traced back to the Arts and Crafts group, which was a reaction against the 19th century’s academic art forms. The design was also influenced by an inflow of Japanese woodblock prints with flowery themes and powerful curves. Art Nouveau was prominent until 1905, but it is now seen as a precursor to Modernism. Art Nouveau started with the purpose of updating the design and rejecting previously established traditional and historic approaches.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Art Nouveau – The Decorative Stylings of the Art Nouveau Movement.” Art in Context. June 13, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/art-nouveau/

Meyer, I. (2022, 13 June). Art Nouveau – The Decorative Stylings of the Art Nouveau Movement. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/art-nouveau/

Meyer, Isabella. “Art Nouveau – The Decorative Stylings of the Art Nouveau Movement.” Art in Context, June 13, 2022. https://artincontext.org/art-nouveau/.