Futurism – Looking Back at the Futurism Art Movement

What is Futurism? It was not only an art movement, but a reaction to the traditional arts and antiquated ideals underlying the cultural structures of Italy. The avant-garde ideals of what Futurism stood for started in a manifesto published in 1909, by its founder, Filippo Marinetti. It stood for the rise of modernity and all things to do with it – think progression, movement, speed, urbanization, industry, technology, locomotion, youth, violence, rebellion, among others.

Table of Contents

Introduction to Futurism

As an art and quasi-political movement from the early 20th century, Italian Futurism started as a concept that seemingly took over, or aspired to take over, the old ways and structures of Italian art and culture. However, it was more than that; it was a politically inspired revolt against the orderliness and current state of affairs of Italy at the time. The Futurism art movement sought to elevate the working classes, celebrate the young, and completely do away with the past.

As Marinetti so boldly declared in the futurism manifesto, “We want no part of it, the past, we the young and strong Futurists!”

Historical Foundations: Italy and Fascism

For a better understanding of what Futurism Art was and what it encompassed, it is important to have context of the historical and political events at the time Italian Futurism developed, and how it eventually spread to other countries like Russia. During 1861, Italy became a unified nation, also referred to as Risorgimento, which means “Resurgence”.

This unification joined the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (this included Sicily and the Southern parts of the Italian Peninsula) and many constituent states of the Italian Peninsula. The Kingdom of Italy, as it was now called, was ruled by King Victor Emmanuel II, who previously ruled as the King of Sardinia. He ruled until 1878, the year of his death. His son, Umberto I, reigned as King from January 1878, but he was assassinated in July of 1900 by Gaetano Bresci, an Italian anarchist.

King Victor Emmanuel III became Italy’s next king and reigned from July 1900 to May 1946, when he formally resigned as King. His son, Umberto II became king only until June 1946. During the reign of King Victor Emmanuel III, he appointed Benito Mussolini as the Prime Minister for Italy in 1922. There is considerable scholarly debate over why he was appointed by the king and the consequences of this.

It is important to note that Mussolini was the main protagonist of Fascism; in fact, he started it in 1919. It was based on his beliefs that democracy was not beneficial to society, social class being a leading cause of this. His goal for the Italian Fascist movement was to unite everyone as one nation, which would then eliminate the ideologies of social class.

Art versus Politics

Many scholarly resources explore the relationship and influence between Mussolini and the Futurism art movement’s founder, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Because of the strong political and propaganda-driven nature of the Futurists, Mussolini is reported to have used many of their tactics, such as the inciting of violence, thee strong advocation of nationalism, as well as the belief in war.

Furthermore, Futurism bridged the gap between the art world and the political world, often using their varying forms of media like imagery and music to reach the masses as propaganda.

Some sources also point to the fact that art and politics should be two separate fields. Futurism and Fascism was an example of how an arts-based movement dipped its toes into the wide and often treacherous waters of politics.

The Bicycles and the Car: Filippo Marinetti

The Futurism art movement started in 1908, when Marinetti’s revolutionary ideas were abruptly awakened by two cyclists. The Futurist pioneer explains his almost mystical and amorous journey driving his new Fiat automobile, or as he liked to refer to it, “beast”, through the streets of Milan, Italy with his friends. He further likened himself and his friends to “young lions” who “ran after Death”, referring to the dangerous nature of driving and speed.

However, the speedy journey only took them so far when he swerved his sports mobile off the road and into a nearby ditch (“wheels in the air”) to deflect from hitting two cyclists. As nearby fishermen pulled his car out of the ditch, Marinetti’s “beautiful shark” was not “dead”, but “alive again, running on its powerful fins!” This experience catapulted Marinetti into a new perspective, and although “bruised”, he went on to declare his “high intentions to all living of the earth”.

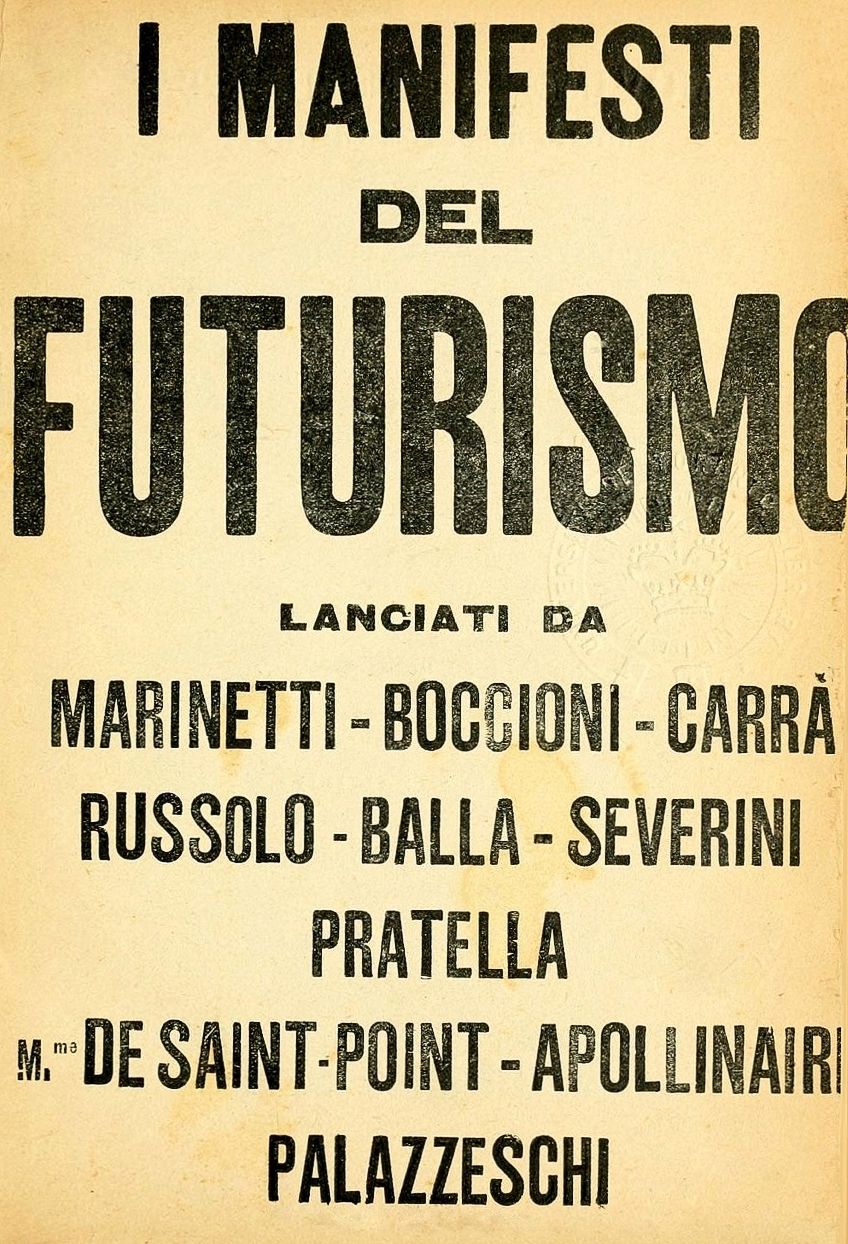

The Futurist Manifesto

The above fender bender between vehicle and bicycle conceived what was later a written declaration by Marinetti, titled the Manifesto of Futurism. It was published in 1909 by the Italian newspaper called Gazzetta dell’Emilia, and then only several days later by the French newspaper Le Figaro. Although this was the initial manifesto, the Futurists continued to publish other manifestos, such as the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting in 1910. This was a leaflet published by the Italian newspaper Poesia, exploring artistic principles not readily discussed in their first publication.

The Futurist manifesto outlined several points as a declaration of what Marinetti and a group of artists and theoreticians – namely, Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, and Gino Severini – all envisioned for the future.

They openly celebrated the ideals underlying progress and seemingly many of the words with “-tion” suffixes at the end, like urbanization, globalization, capitalization, modernization, industrialization, and most importantly, motion.

It should be noted there was more than only Futurism paintings and Futurism sculpture. The art movement also embraced and manifested itself across various artistic modalities, including Futurist drawings, music, literature and poetry, photography, architecture, film, dance, and many other forms of which they also wrote about. It was a resurgence of new perspectives like speed, action, violence, and the ideals that work is done with an aggression – “no work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece.”

Violence and an “aggressive character” were at the ever beating and protesting heart of the Futurists; their poetry would be used as a “violent attack on unknown forces, to reduce and prostrate them before man.” The group sought to eliminate and destroy everything related to the past, morals, utilitarian values, beauty, and women.

Stating passionately and rebelliously, “We will glorify war – the world’s only hygiene – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman. We will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind, will fight moralism, feminism, every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice”. The Futurists willingly and forcefully wanted to tear down all traditional and classical notions of life and the arts from its longstanding pedestals. They wanted to “free” their land, Italy, from the “smelly gangrene of professors, archaeologists, ciceroni, and antiquarians”, comparing museums to cemeteries.

The Futurists introduced a “new beauty”, as they called it, which was “the beauty of speed”. They asked, “Why should we look back, when what we want is to break down the mysterious doors of the Impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, because we have created eternal, omnipresent speed”.

They were tireless in their pursuit, declaring, “Our hearts know no weariness because they are fed with fire, hatred, and speed!”. The group was aware there would be people against them who might possibly “hurtle” to kill them, but they kept their vision to “hurl defiance to the stars!” and “erect on the summit of the world”.

Key Influences and Concepts of Futurism

Futurism as an art movement can be identified by several key words, for example, speed, movement, technology, action, defiance, violence, passion, and modernity. Most of these key words are brought to life on the canvas filled with colors and subject matter all rushing in shape and form, and, similarly, becoming one and the same. The Futurist artists produced many great works and drew influence from other art movements. These are discussed in more detail below.

What Art Movements Influenced Futurism?

Before we move on to some of the key concepts of the Futurism art movement, some of the main influences from other art movements will provide more context. The Futurists did not have a unique style when they first started, although their inspiration came from prominent movements like Cubism, Divisionism, and Post-Impressionism.

Cubism was one of the primary influences on Futurism, and several members of the group living in Milan were exposed to Cubist artworks when they visited Paris in 1911. At the time, Severini lived in Paris and was already familiar with Cubism. He also felt his colleagues in Milan needed exposure to the more avant-garde art styles in France.

Although the Futurists from Milan borrowed considerable stylistic principles from Cubism, they did not agree with their ideologies, and believed they were too rooted in academic principles with seemingly passive subject matter.

The Futurists wanted to portray subject matter that literally moved beyond the canvas and infiltrated Italy and the way people lived.

Other art movements that influenced the Futurists included Divisionism, a color theory within the Neo-Impressionist art movement. The process involved applying “dots” of color pigment next to the other on the canvas. This style was like Pointillism in that artists would apply color in “dots” or “points”. The notable difference between the these was how Divisionists kept each “dot” of color separated. Some Futurist painting examples include Giacomo Balla’s Street Light (1909) and Gino Severini’s Souvenirs de Voyage (1911), among others.

Within these stylistic influences, it is clear that the Futurist painters experimented with vibrant colors (described by some art critics as “electrifying” and “prismatic”), how these colors created light and dark contrasts, and importantly how they created the element of speed, dynamism, and movement. This use of color and light was a key trait among the Post-Impressionists.

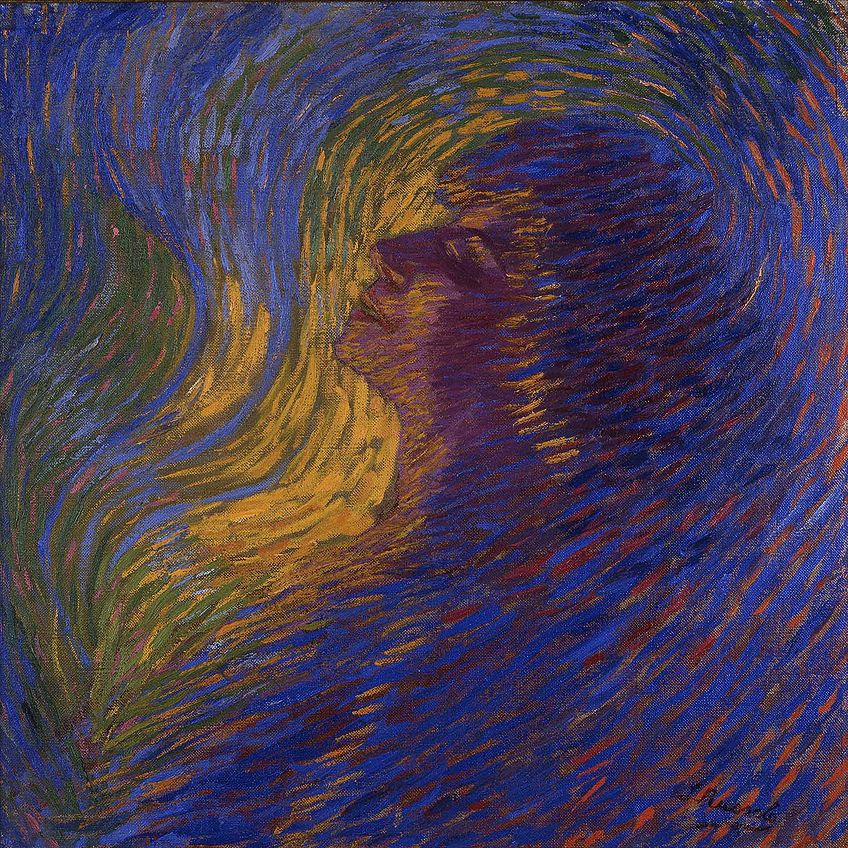

Speed (“Universal Dynamism”)

As previously noted, speed and the portrayal of it was a key focus for the Futurists in their art. This idea informed many of their compositions, on canvas and off, as well as their underlying stylistic objective, which they referred to as “Universal Dynamism”. This pointed to how each object portrayed in an artwork was part of the other objects – there was no intentional separation of objects – everything was absolute, placing the “spectator in the center of the picture”.

This was further discussed in their other manifesto, Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting (1910). The Futurist artist’s “growing need of truth” could not accept the ways in which forms and colors “have been understood hitherto”. They further explained the discrepancy between the static form and the form in motion, referring to it as the “gesture” they aimed to “reproduce on canvas”. This would no longer be “a fixed moment in universal dynamism. It shall simply be the dynamic sensation itself”.

An example of this dynamic style is described in the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting (1910): “The sixteen people around you in a rolling motor bus are in turn and at the same time one, ten, four, three; they are motionless and they change places; they come and go, bound into the street, are suddenly swallowed up by the sunshine, then come back and sit before you, like persistent symbols of universal vibration.”

Futurist paintings were often depicted using images that appeared fractured and almost geometric in their composition while simultaneously appearing dynamic and in motion. The foregrounds and backgrounds would melt into one another and the subject matter would pull the viewer into the frame. The way the brushstrokes were used on the canvas created a further dynamism and urgency to the paintings.

An example of the above is seen in Umberto Boccioni’s painting, The City Rises (1910). The composition depicts industrialization with the buildings in the background and construction workers visible as small figures. Boccioni portrayed scenes from the building of an electric power plant outside Milan.

The foreground depicts workers trying to gain control of a horse, which appears overpowering as the central figure. Surrounding the horse are other horses and figures dispersed among the other. The sweeping brushstrokes create a scene of speedy movement and angst – each segment of the canvas is filled up with an action – it is as if the viewer is given access to just one screenshot of a larger event taking place.

Upon closer examination, the brushstrokes are applied alongside one another in loose flicks of blues and red, with white, smoke-like streams of paint depicting an element of light. It is important to note how Boccioni did not use any shadows in this painting; the white paint creates sufficient contrast. The application of the paint and the direction of perspective created by the placement of the subject matter almost reins the viewer in to move a certain way with the movement of the painting, much like the way the horses are reined in by the figures.

Apart from the stylistic elements of the above work, the painting symbolizes the onset of industry in Italy at the time it was painted. The advancements of urbanization led everyone to gain new perspectives of life and what was in store for them. Each figure painted is an everyday man and no one of particular importance. This further touches on the element of the masses.

Famous Futurist Artists and Artworks

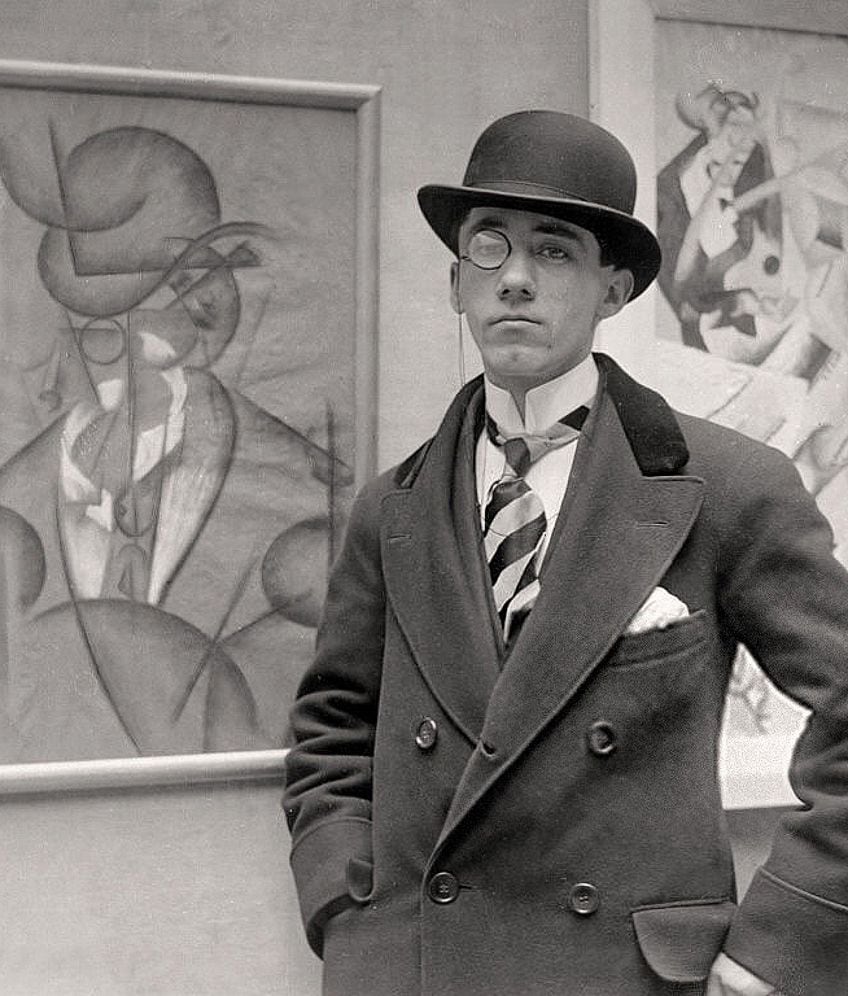

In 1912, the Futurist’s first exhibition was in Paris at the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery. The artworks on display included some of the primary figures of Futurism. While there were many more Futurist artists, below, we will look at the key figures who developed this art movement and some of their artworks as examples of what Futurism as an art intended to portray.

Carlo Carrà (1881 – 1966)

Carlo Carrà was a painter and art writer born in Quargnento, Piedmont, Italy. He was a mural decorator from the age of 12 and during the years of 1899 to 1900 he traveled to various European cities like Paris and London. In Paris, he learnt about French Art and decorated pavilions for the Paris Exposition of 1900. During 1906, a few years after moving to Milan, he studied at the Brera Academy.

He eventually joined the Futurism art movement and later went on to produce artworks that explored other concepts and styles like still lifes, metaphysical art, anarchy in art, as well as landscape paintings. He was inspired by artists like Giotto because of the way he depicted the form of bodies. He worked with famous artists of his time like Giorgio de Chirico, who founded the movement called Metaphysical Art.

Funeral of the Anarchist Galli (1910-1911) was a famous artwork by Carrà depicting the funeral of Angelo Galli, an Italian anarchist who was killed in 1904 during a strike. The painting is based on Carrà’s observations of the event after it happened. It shows the police intercepting the group of anarchists before they can enter the cemetery to avoid any further rioting.

Carrà described the event as follows: “I found myself unwillingly in the centre of it, before me I saw the coffin, covered in red carnations, sway dangerously on the shoulders of the pallbearers; I saw horses go mad, sticks and lances clash, it seemed to me that the corpse could have fallen to the ground at any moment and the horses would have trampled it. Deeply struck, as soon as I got home I did a drawing of what I had seen”.

The painting itself depicts Galli’s coffin in the top center portion of the composition, it appears unevenly balanced between the arms trying to hold it up while moving forward. The artist utilizes dark colors, angular and rounded forms and lines. Semi-indistinguishable figures almost overlap one another to create the effect of movement and action.

Carrà’s influence from Cubism is also evident in his use of fracturing the image with, as described in the Futurist Manifesto, “sheaves of lines corresponding to the conflicting forces”. The primary objective of these “force-lines” was to “encircle and involve the spectator” in order to become a part of the scene and not apart from the scene.

Other works by Carrà also show his influence from the Cubist art style, for example, Woman on the Balcony (1912). It appears geometrically dominated from the fractured shapes making up the whole composition, which in turn was used to portray movement and not only a static subject matter – something the artist believed limited the Cubists.

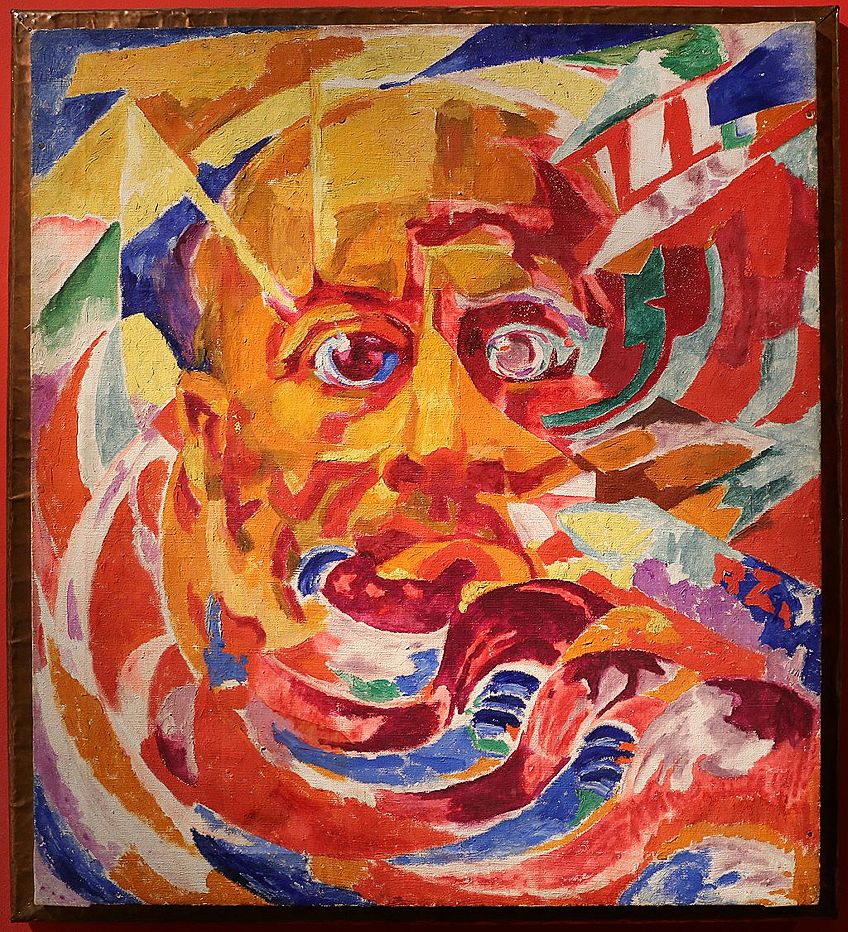

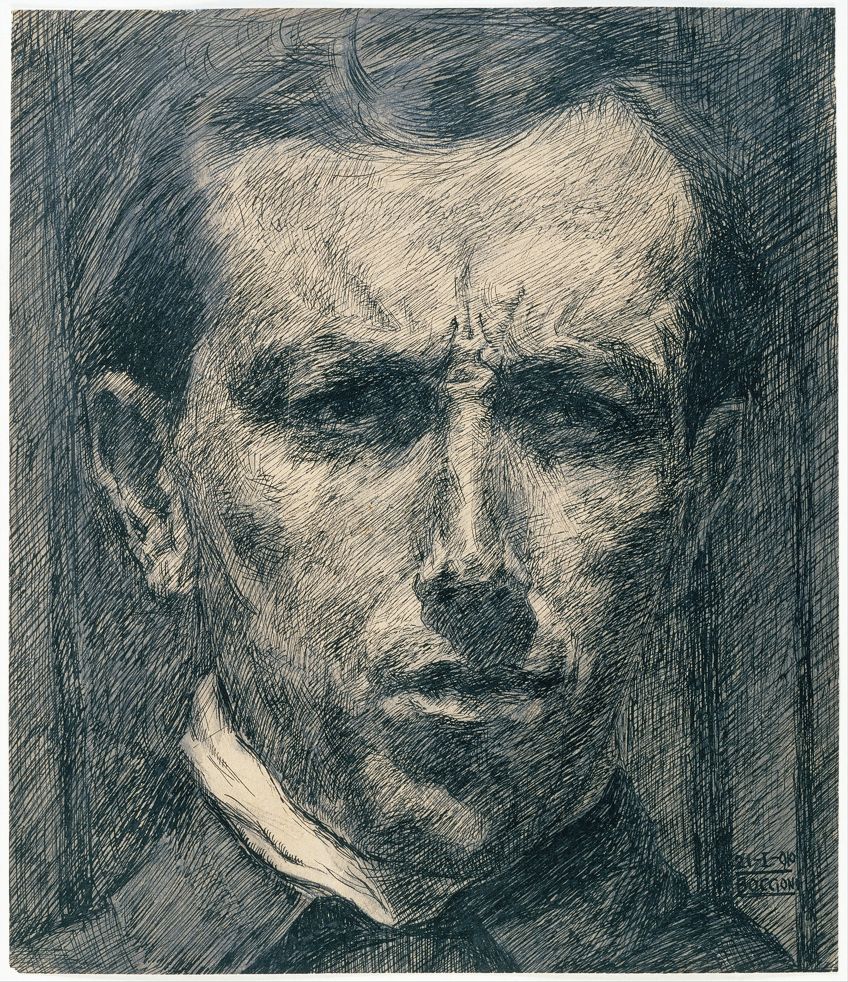

Umberto Boccioni (1882 – 1916)

Umberto Boccioni was a painter and sculptor, born in Southern Italy, Reggio di Calabria, but grew up in Northern Italy’s, Forlì and Padua throughout the course of his childhood. He moved to Sicily with his father in 1897 at 15 years old. He eventually moved to Rome a couple of years later and studied art at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Roma. He also studied under other prominent artists like Giovanni Mataloni and Giacomo Balla.

In the early 1900s, he worked as an illustrator and traveled extensively across Europe, notably doing work for the publishing house Stiefbold & Co. He moved to Paris, where he familiarized himself with the art styles of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. He also traveled to Russia, where he stayed for several months. His experience in illustration and working in other European cities gave him in-depth knowledge about artistic practices for that time.

He eventually moved to Milan during the year of 1907 and met several important figures spearheading the Futurist art movement, namely, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the founder. He provided the group with a strong artistic theoretical foundation. During the year of 1911, he visited Paris with several of his Futurist friends, where they saw Cubism art. During 1912, after he went to various art studios of well-known sculptors, he became a sculptor.

Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), made of bronze, is a famous Futurism sculpture. It depicts Futurists’ principles of speed, movement, and dynamism. The figure’s head appears to be a helmet and he does not have distinguishable arms. What is important about this piece is that Boccioni created the figure as one with his environment. In other words, the fluid and floating shapes around his body is seen as the air itself as he walks.

Boccioni’s preoccupation with the moving figure is echoed in his series of paintings called Dynamism of a Cyclist (1913) and Dynamism of a Soccer Player (1913). The technological advancements of locomotion, for example, bicycles, cars, and trains, introduced novel sensations like speed. This was undoubtedly a major influence on Boccioni as well as many other artists alongside him.

Gino Severini (1883 – 1966)

Gino Severini was another important figure in the Futurism art movement. He was born in Cortona, Italy, and during 1899, he moved to Rome with his mother and worked as a shipping clerk while making art. He eventually received a sponsorship for art classes, which he attended for two years. He met Umberto Boccioni during 1900 and both artists learnt the Divisionism art style from Giacomo Balla, another prominent Futurist artist.

Severini moved to Paris in 1906, where he gained considerable exposure to the avant-garde art scene of the time, including well-known artists like Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Guillaume Apollinaire, to name a few. After he joined the Futurist group, he became a key catalyst for the artistic progression of the Italian artists, connecting them to French art and artists.

Severini portrayed movement and the central idea of dynamism in a different way than the other Futurists – he often opted for dancing figures as opposed to the focus on mechanization. An example of this is seen in his painting, Dynamic Hieroglyph of the Bal Tabarin (1912) and Dancer at Pigalle (1912).

In Dynamic Hieroglyph of the Bal Tabarin, Severini depicts the familiar Cubist style of fractured images and repeating shapes and colors. The painting focuses on two women dancing, identified by their purple and pink dresses and hair color – blond on the left and black hair on the right. There are various other figures dispersed around the two dancers, which emphasizes the movement and liveliness of the cabaret.

Luigi Russolo (1885 – 1947)

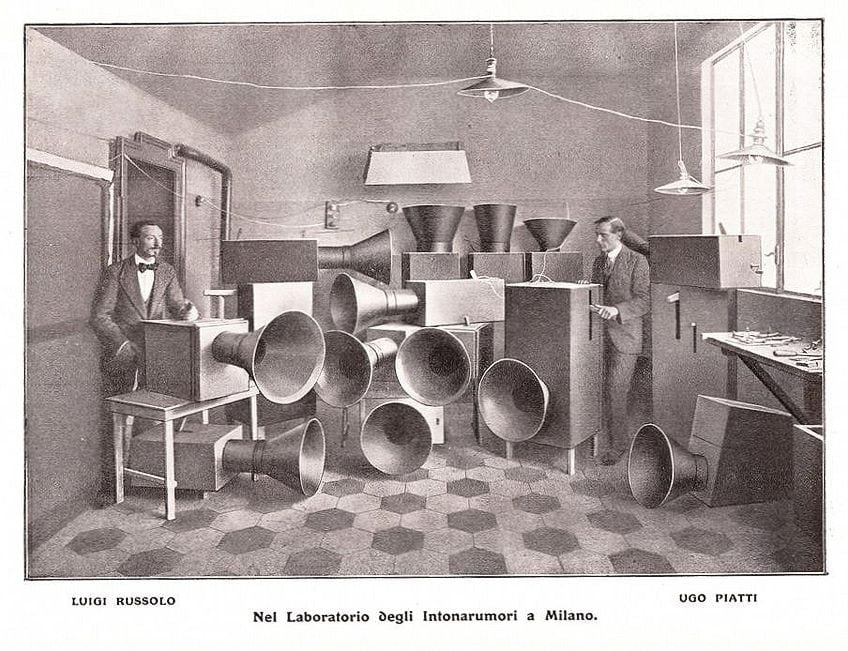

Luigi Russolo was born in Portogruaro, Northern Italy. He was a painter and composer, but also importantly, the pioneer of noise art and noise music. He also built musical instruments as experiments. His noise-making “devices” were called Intonarumori, and he used these to give performances, described as noise orchestras. Russolo and Marinetti utilized these musical discoveries within the Futurism movement in 1914 when they put on a concert using the Intonarumori.

Russolo also wrote the manifesto, The Art of Noises (1913), which sees the world and how the Futurists saw it from a musical perspective. Russolo referred to the new sounds that came from industrialization and the modernized urban environments, specifically speed and the bustling noises of city life. He believed these sounds, or “noise” only occurred from machines during the 1800s. These new concepts also led him to see the need for different musical compositions and instruments.

Giacomo Balla (1871 – 1958)

Giacomo Balla was born in Turin, Northern Italy. He studied music as a young boy and worked at a lithograph print shop when he was nine, which led him to study art after his schooling years. He worked as an artist in Rome, where he moved during 1895. He was a key artist who taught other Futurists like Gino Severini and Umberto Boccioni in the Divisionism art style.

When he joined the Futurist group, he painted his famous artwork, Street Light (1909), which depicts an electric street light, a new technological development of the time. Balla, inspired by this new advancement of technology and modernism, used various colors to indicate the dynamism of the glowing light powered by electricity.

Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912) is another example of Balla’s focus on depicting speed and movement. In this painting, the dog and the woman’s feet compose the subject matter. It is almost as if a black cloud-like form is around the woman’s feet and dress, including the dog’s feet, ears, and tail. Upon closer inspection we can see that these parts of the subject matters are multiplied, appearing almost transparent. This effect suggests the act of movement and walking forward.

Furthermore, this effect was inspired by the latest photographic innovations, specifically referred to as chronophotography, which recorded multiple movements shown in a single image. This was a useful technique for the Futurists as it enabled them to depict the essence of speed and movement more accurately.

Girl Running on Balcony (1912) is another depiction of multiple frames of motion, this time of a girl running. Here, we can also see the specific brushwork in the Divisionism and Pointillism styles, where the dots and rich colors positioned next to the other create a sense of depth. The image of the child is not detailed either, and Balla portrays the child running – the action of it – as the primary focus of the artwork, yet again staying true to the principles of Futurism.

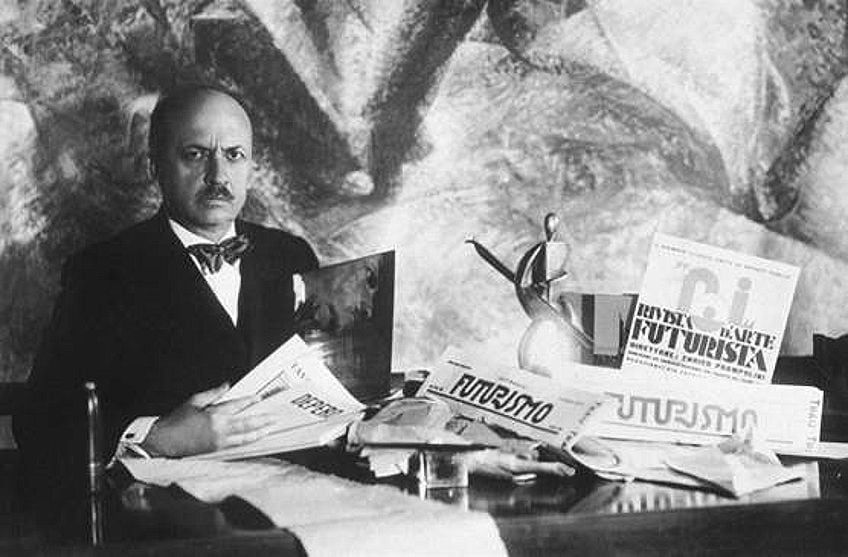

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876 – 1944)

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was the founder of Futurism and the author of the Futurist Manifesto in 1909. He was born and grew up in Alexandria, Egypt. He showed a keen interest in literature, introduced to it by his mother. He started a school magazine when he was 17 years old, called Papyrus.

Marinetti completed his bachelor’s degree at the Sorbonne University in Paris in 1894. He initially started his education in Egypt and finally graduated at Italy’s University of Pavia in 1899 with a law degree. He chose a literary career path over being a lawyer, and this led him to write in different genres like poetry and theatre, among others.

Back to the Futurism

Although Futurism started with a strong artistic foundation, it had political involvements with the Fascist movement in Italy at the time. Some artists left the group and pursued different artistic styles. The involvement with Fascism also put many artist’s reputation at stake. During World War I there was a “Second Futurism” that supported Mussolini. Many Futurist drawings were used as the imagery to produce propaganda. When Marinetti passed away in 1944, the movement did not continue.

Futurism lived on in many other art movements influenced by the progressive and passionate attitude it held, namely, Art Deco, Dadaism, Vorticism, Constructivism, and Surrealism. Futuristic art can also be viewed in more contemporary movements like Cyberpunk, also using the principles of Futurism’s focus on technology. Neo-Futurism was started in 1988 in Chicago within the theater industry, which borrowed the principles of speed from the original Futurism movement.

While there is so much more to say about Futurism as an art movement, it is worth noting the power and force it created, which was paralleled with the force portrayed in the Futuristic art created. It was a revolutionary platform where people could express themselves openly with wild abandon and aggressive passion, specifically the youth. As we go back to the Futurists, we see the obvious excitement of a group of people who closely identified with progressive thinking and living, deeply affected by the progressive developments of technology in their time.

Take a look at our Futurism art webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Futurism?

The Futurism art movement was a reaction against the traditional, old, and outdated art forms from the Classical eras. It started in Milan, Italy, during 1909. It was a group of multidisciplinary artists, writers, and theorists who all believed the modern age of urbanization and industrialization was the only way forward for the future of Italy and its people. Although it was at first an art movement, it had strong political implications and involvements.

What Are the Characteristics of the Futurist Art Movement?

The primary characteristics of the Futurist art movement were to celebrate and portray a “universal dynamism”, in other words, movement, speed, violence, and a strong opposition to the past. The new developments of locomotion during that time gave the Futurists a new perspective about life and progress, which was at the core of their attitude and artistic principles. The movement was also politically engaged with the uprising of Fascism during Italy, which led to many scholarly debates about the involvement with Mussolini and Marinetti.

Who Were the Futurists?

The Futurism art movement was founded by Italian Filippo Tommaso Marinetti when he published his declaration entitled, The Futurist Manifesto. Several other artists joined the group over time, including Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Fortunato Depero, Luigi Russolo, and Gino Severini, among others.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Futurism – Looking Back at the Futurism Art Movement.” Art in Context. April 16, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/futurism/