Arte Povera – What Was the Arte Povera Movement?

Originating in Italy towards the end of the 1960s, Arte Povera was an art movement that made use of simple and ordinary materials within the artworks that were produced. Interested in challenging the traditional exclusivity that existed in the mainstream art world, Arte Povera went on to explore a wide range of materials and concepts that were unconventional and thus thought to be too eccentric for art. While only a small group of artists experimented with this style, truly unique and unusual artworks emerged from this movement.

Table of Contents

- 1 What Is Arte Povera?

- 2 The Beginning of the Arte Povera Movement

- 3 The Type of Artworks to Emerge

- 4 Miracolo Italiano

- 5 What Carried Arte Povera to the Public’s Attention?

- 6 The Concepts and Styles of Arte Povera

- 7 Careful Curation of the Arte Povera Movement

- 8 Some Famous Arte Povera Artists and Their Artworks

- 8.1 Artist’s Shit (No. 4) (1961) by Piero Manzoni

- 8.2 Structure for Talking While Standing (Minus Objects) (1965 – 1966) by Michelangelo Pistoletto

- 8.3 Untitled (Living Sculpture) (1966) by Marisa Merz

- 8.4 Floor Tautology (1967) by Luciano Fabro

- 8.5 Untitled (Sculpture That Eats) (1968) by Giovanni Anselmo

- 9 The Legacy of Arte Povera

- 10 Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Arte Povera?

Meaning “poor art”, the Arte Povera movement was made up of a group of young Italian artists who were active in the art scene during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Characterized through its use of paper, jute, wood, coal, rags, twigs, fire, and other everyday materials, Arte Povera dismissed all of the principles related to figurative art and classicism, with its artists choosing to rather create artworks from common supplies.

The art movement was mainly based in the Italian cities of Turin, Rome, Milan, Genoa, Venice, Bologna, and Naples.

The name “Arte Povera” was first invented by the Italian art critic Germano Celant in 1967, who went on to organize many revolutionary Arte Povera exhibitions. Celant’s efforts helped to create a social identity for the artists who made use of “poor” materials in their conceptually rich artworks. However, the term was only introduced in Italy during a period of turmoil towards the end of the 1960s when artists began to take a more radical stance against the conservative ideals that ruled art.

The official starting point of Arte Povera was said to be launched by the 1967 Im Spazio exhibition that took place in Genoa, Italy. As the show was curated by Celant, this allowed him to become one of the major advocates that came out of the Arte Povera movement. This then led to him putting together another progressive exhibition the following year, which further cemented the fundamental role that he played within this expanding art movement.

Viewed as a radical art movement, Arte Povera artists criticized the philosophies and ideals of traditional establishments of government, industry, and culture through the types of art that they created.

It has long been thought that Italian painter Alberto Burri was the father of Arte Povera, despite his works predating the movement. Burri was known for his exceptional artworks that were made using unconventional materials towards the end of the 1940s, as he experimented with both the Fluxus and Noveau Réalisme styles in addition to Arte Povera.

The Beginning of the Arte Povera Movement

Lasting for a relatively short period of time between 1967 and 1972, the Arte Povera movement explored a wide range of materials beyond the traditional ones. The art style emerged in Italy due to the decline that was seen in abstract painting, as well as the sudden revitalization and interest with past avant-garde approaches to art like Surrealism.

Artists felt inspired by the type of artworks that were produced during the 1920s and 1930s and felt a great inclination towards this type of artmaking.

As an art movement, Arte Povera was considered to be one of the most noteworthy and important styles to come out of Southern Europe in the late 1960s. The movement introduced artworks that displayed a distinct reaction against the contemporary abstract paintings that had commanded the European art market throughout the 1950s. Rejecting the concept of American Modernism, Arte Povera went on to further dismiss any ideals that seemed to display enthusiasm about technology’s growing influence over the art world.

Artists who identified with the ideals of Arte Povera went on to further distinguish themselves by focusing on sculptural works as opposed to painting. The types of artworks produced seemed to echo the Post-Minimalist inclinations that existed in 1960s American art, yet its hints of past, location, and memory retained a decidedly Italian aesthetic and characteristic.

When considering the types of “impoverished art” that appeared, certain traits made these Arte Povera artworks instantly recognizable and different from other types of art.

Throughout the movement’s height, about a dozen Italian artists stood out due to their unique Arte Povera artworks that were made. These artists typically made use of commonplace and unprocessed materials that directly referenced the pre-industrial age, such as rocks, paper, bits of rope, and pieces of clothing. The aim was to create art out of “cheap” materials that were repurposed so that these pieces could exist as a statement within the modern and traditionalist art world.

The purpose of using these types of materials was to present a somewhat gaudy provocation to the conventional notions of value and respectability that already existed in the art world. What made certain artworks stand out was the contrast that was created between the unpolished materials and the references that were directed towards the growing consumer culture.

Additionally, most artworks included an understated critique of the industrialization and mechanization that was occurring in Italy at the time.

Arte Povera essentially believed that modernity existed as a danger that could destroy all collective memory and tradition, which were key aspects associated with Italian cultural heritage. Thus, Arte Povera artists sought to juxtapose the old with the new in their artworks so that they could further complicate their audience’s sense of passing time when attempting to make sense of a work.

While Arte Povera was quite short-lived, its great influence on later art movements has been lasting. Dubbed the Italian contribution to the development of Conceptual art, Arte Povera demonstrated the profound effect that it had on the art world through the rise of other art styles. As the style was able to seamlessly combine the natural and the artificial, the rural and the urban, as well as Western modernity with Mediterranean life, the impact of Arte Povera can still be seen in different art styles today.

The Type of Artworks to Emerge

Artists who chose to experiment with the Arte Povera movement typically broke away from the norms of the mainstream art world. They were defined as “anti-elitist” and were determined to help create an art movement that remained unfixed yet sympathetic to the current values that ruled what art stood for. As a powerful and avant-garde movement, Arte Povera upheld a type of art that ran against the popular styles of the art world and disputed the commercial trends of the Western world during the mid-1960s.

In response to the turbulent Italian economy at the time, many Arte Povera artists preferred an art form that was more conceptual, innovative, and less superficial than other styles.

Thus, artists worked with a variety of aesthetic disciplines which included sculpture, performance, and assemblage in addition to painting. Some artists even took advantage of the social and political power of the Arte Povera movement and used it as a channel for expression within their artworks.

Despite all of the different artmaking schools, Arte Povera has most often been associated with the technique of assemblage. Through using this style, Arte Povera displayed its interest in the materiality and physicality of its artworks. The dynamic between natural features and man-made ones was explored, with artists making use of industrial, organic, and transient materials to emphasize this.

Additionally, gallery spaces ended up becoming part of the overall experience as well, as artworks aimed to call attention to the venue as well.

Arte Povera artists worked in many different ways and frequently switched between creating works of great physical presence to much smaller pieces. Through the absurd and comical juxtapositions seen in the artworks, artists were able to evoke a sense of modernization and its inclination to ruin experiences of locality and memory. Despite this, Arte Povera’s art continued to push forwards into the future and was said to demonstrate some commonality with other experimental movements like Surrealism, Dadaism, and Constructivism.

Miracolo Italiano

The post-war period in Italy, which was further emphasized by the infamous economic boom in the 1960s, gave artists more freedom and independence within the art world due to the inflation in currency. This period was frequently referred to as Miracolo Italiano, which translated to “Italian miracle”. In the years that passed after the Second World War, Italian society felt a sense of hope which transformed into experimentation and rebellion in a variety of fields, including artmaking.

However, this duration of elation did not last very long, with the resulting disillusionment and skepticism acting as the launching point for the emergence of the Arte Povera movement. Arte Povera was born in open contention with contemporary art, with the controversy further building after artists rejected traditional techniques and chose to make use of “poor materials” instead.

As Arte Povera was connected to nature and revealed an interest in environmental issues, seen through the materials used, the movement raised many questions and concerns.

What Carried Arte Povera to the Public’s Attention?

Another pivotal moment that was believed to draw massive attention to the development of the Arte Povera movement was an exhibition that took place in Rome in 1968. Art dealer Fabio Sargentini went on to invite artist Pino Pascali to present some of his unique works at his gallery, Galleria L’Attico. Sadly, Pascali passed away after a motorcycle accident before the exhibition began, with Greek artist Jannis Kounellis being asked to take his place.

What drew great attention to the exhibition, as well as to the Arte Povera movement in general, was the audacity and peculiarity of Kounellis’ show. The art piece that he submitted was made up of a dozen live horses tethered to the gallery walls and was met with much shock by the audience. The artwork, titled Untitled (12 Horses), became a legendary piece of Arte Povera art and was extremely popular with both the public and critics. Kounellis’ piece expressed the idea that art could be made from absolutely anything and did not necessarily need to be commercially feasible all the time.

While other moments have also been dubbed as the start of the Arte Povera movement, this particular exhibition, thanks to Kounellis’ truly startling work, has widely been described to mark the birth of Arte Povera art.

The Concepts and Styles of Arte Povera

While Arte Povera was frequently referred to as “poor art”, the movement did not imply a lack of money. Rather, one of the main concepts of Arte Povera stood for the ability to be able to make art without the restrictions of all traditional practices and materials. Arte Povera simply materialized from a network of urban cultural activity that was occurring during the 1960s within Italy, with artists choosing to focus on these changes within their artworks.

At its essence, the concept of the Arte Povera movement was to simply return to ordinary objects and messages within art.

Everyday occurrences were seen as meaningful and worthy enough of being explored within an art context, with elements of dynamism, energy, and nature being included. The body and behavior were regarded as art forms within themselves, with Arte Povera artists making use of these concepts to incorporate the significance of life in the majority of the artworks that were created.

Another concept of Arte Povera art was its ubiquity and affordability. The type of materials used fit the idea of commonality surrounding Arte Povera, which allowed the style to employ revolutionary avant-garde tactics in the works that were created. This was mainly seen in the unconventional sculptures, performance pieces, and installations that emerged. In their efforts to join life with art, Arte Povera artists provoked a personal response to each of their art pieces, stressing the originality present within this interaction between viewers and the work.

Arte Povera Sculpture

The artistic medium that is the most closely associated with the Arte Povera movement is sculpture. Caused partly from artists’ dismissal of abstract and minimalist painting techniques, which commanded the art market at the time, artists strove to rather create objects that needed physical interaction from their audience and environment in order to work.

A well-known example of this is Giovanni Anselmo’s 1968 piece, “Untitled”, which needed the gallery to constantly change the lettuce at the middle of the sculpture to sustain its honesty.

Arte Povera sculptures also worked to connect the natural and the unnatural by attracting attention to the difference that existed between the two. This can clearly be seen in the types of materials that were chosen for the artworks, as organic materials were often joined to geometric structures when creating the sculpture. While this pairing was thought to be incongruous at times, the importance of the artworks lay in the juxtaposition created between the value and status placed on art.

A Key Idea of Arte Povera

Possibly one of the most significant ideas associated with the Arte Povera movement was the concept of Ground Zero. Implying a starting point for the rejection of the artistic ideals that came before them, artists broke countless categories and boundaries that dictated the artmaking process in the development of Arte Povera.

What remains interesting about this concept is that while artists did not care much about how the art market perceived them and proceeded to mock them, these actions firmly encased Arte Povera into history.

Careful Curation of the Arte Povera Movement

An important aspect of the Arte Povera movement was the process of curation. Credited with the success of the art movement, Germano Celant went on to carefully select the type of artworks that would later be included in the first official Arte Povera exhibition. Revered as the head architect of Arte Povera, Celant’s meticulous decisions helped form the ideals of the movement, which was eventually regarded as a cohesive style when it finally emerged.

Several of the artists chosen by Celant had already been associated with prior art movements such as Abstract Expressionism. Their inclusion into the original Arte Povera exhibition gave them a new opportunity for crucial significance within the art world, with their placement in relation to new artists demonstrating their newfound status.

In order to better define Arte Povera, Celant also described it alongside other similar styles like Land Art, which helped increase the movement’s overall image.

Some Famous Arte Povera Artists and Their Artworks

As it was a very niche movement at the time, all of the Arte Povera artists who experimented with this incredibly outrageous style were Italian. Due to this, a very select group of creatives are known for their participation in the movement, as well as the truly revolutionary artworks that they created. Below, we will be exploring some of these iconic Arte Povera pieces along with their equally significant creators.

Artist’s Shit (No. 4) (1961) by Piero Manzoni

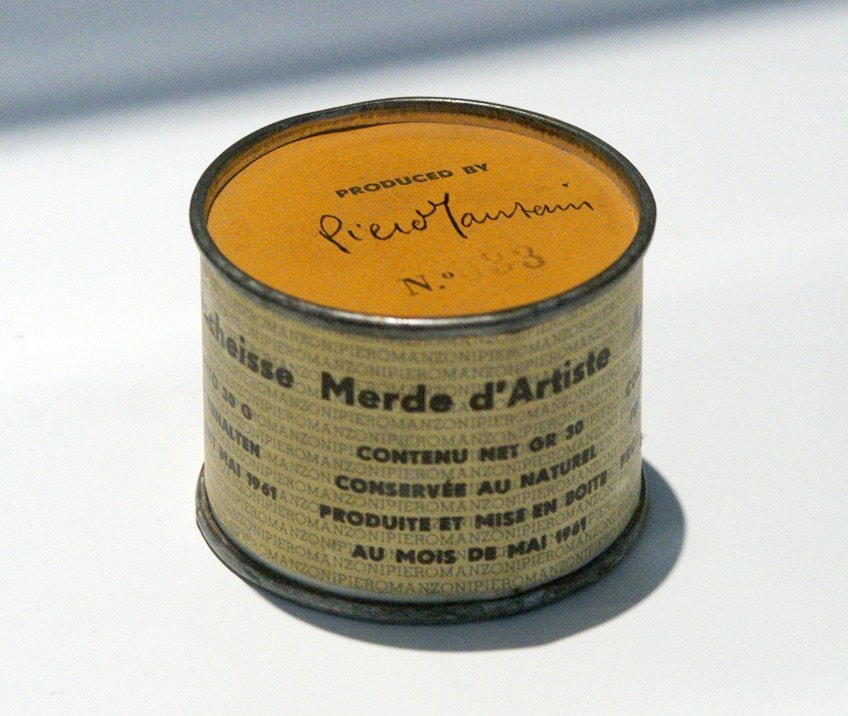

One of the most celebrated artworks within art history was created by Piero Manzoni in 1961 and titled Artist’s Shit (No. 4). Foreshadowing the emergence of Conceptual Art, Manzoni reacted to the abstract paintings that were dominating artistic society at the time within this artwork. Using straightforward concepts and an amusing subversion to contest the limitations of standard artistic practice, Manzoni presented a tin that he supposedly filled with 30 grams of his own excrement.

Today, the true contents of the tin still remain unknown.

Beginning his career as a self-taught painter, Manzoni was greatly influenced by avant-garde practices in the art world. As his style developed, he started to question the traditional methods of artmaking and the true interpretations of artistic creation. He is not always regarded as a true member of the Arte Povera group as he, unfortunately, passed away before the first exhibition. Despite this, Manzoni is often considered to be an important precursor to the movement and his artworks reflected the core principles of the style.

What makes this artwork so interesting is that Manzoni went on to sell the tin to collectors at the same weight price as gold.

This gesture shocked the art world, with Artist’s Shit (No. 4) being viewed as completely scandalous. However, Manzoni’s actions also revealed the unlimited possibilities that could be done with the simplest materials within the Arte Povera movement. He produced 90 identical cans that were labeled in the same way, which existed as a statement that mocked the practices of mass production and consumption within society.

Structure for Talking While Standing (Minus Objects) (1965 – 1966) by Michelangelo Pistoletto

An important figure within the Arte Povera movement was Michelangelo Pistoletto, who continues to produce art today. Acknowledged as one of the main representatives of Arte Povera, Pistoletto produced a series of iconic works throughout the movement. His artworks traditionally dealt with themes of contemplation and the combination of art and everyday life. One of his well-known works, Structure for Talking While Standing (Minus Objects) was produced between 1965 and 1966 and can be viewed at the Pistoletto Foundation in Italy.

This sculpture was part of a series of other sculptures which were all intended to signal the “less-than-whole” quality of the Italian economic growth that occurred during the middle of the 20th century.

This sculpture remained incomplete as it essentially required participation and activation through the activity of the audience so that they could fully understand the work. By including the term “Minus Objects”, Pistoletto implied that the artwork could only be fully realized through the inclusion of human interaction.

“Structure for Talking While Standing (Minus Objects)” was said to have been inspired by marks on the wall that are created by people leaning against them.

Based on this revelation, Pistoletto’s sculpture was designed to be leaned on whilst having a conversation with others, as it provided a place to rest one’s arms and feet. Thus, the first part of the title, “Structure for Standing While Talking” went on to imply the creation of a physical bridge that could facilitate conversations between viewers.

Untitled (Living Sculpture) (1966) by Marisa Merz

As the sole female member of the Arte Povera movement, Marisa Merz was an incredibly valuable artist. Married to fellow Arte Povera artist Mario Merz, she began to produce her own artworks in 1965. Her style effortlessly blended objects and situations from her daily life within the paintings, sculptures, and installations that she created. One of her iconic works, which she produced in 1966, was Untitled (Living Sculpture).

This artwork consisted of a large hanging sculpture that was made up of 26 hollow twisted tubes of shiny aluminum.

Merz created this sculpture by stapling commercially available pieces of metal together in her kitchen before the artwork was selected for exhibition. By molding tubes that were open at their ends so that they could vertically hang in the gallery space, Merz attached about 32 tangled elements to create one giant coil. This spiraling form was attached to the ceiling of the gallery and proceeded to hang at uneven intervals. Some of the coils were within reach of the floor, which further demonstrated their difference in height and length.

Untitled (Living Sculpture) completely overwhelmed yet simultaneously defined the space it occupied. As Merz configured the sculpture for each new space where it hung, the artwork slowly developed a relationship with its surroundings and the different proportions of every room. This emphasized how hard Merz worked to ensure that no division between any elements could ever be seen within her artwork.

Ultimately, Merz was able to create a sculpture that went through a process of renewal each time it was reinstalled.

Floor Tautology (1967) by Luciano Fabro

Another well-known artist who experimented with Arte Povera was Luciano Fabro, who was viewed as a conceptual artist as well. Creating sculptures that were quite abstract in nature, Fabro went on to play around with a variety of industrial and natural materials within his Arte Povera artworks. A famous sculpture of his, created in 1967, is his Floor Tautology. This artwork consisted of an area of polished floor that was closed off and covered with sheets of newspaper to dry in the gallery space.

The creative process behind Floor Tautology was more important than the final result of the artwork. Fabro’s objective with this piece was to glorify an everyday and ordinary function, such as cleaning a part of the floor, past the point of a simple housework task until it reached the ranks of fine art. The placement of the newspaper also raised questions about the notion of value that was paid to more traditional artworks.

By making an overlooked aspect of the room the center of attention, Fabro forced viewers to reevaluate what they considered as art.

Additionally, Floor Tautology invited consideration and encouraged viewers to spend time thinking about the effort that those responsible for cleaning expend, which is not something that is usually given much thought. Due to this, Fabro’s artwork indirectly asked the audience to invest some effort in keeping the floor clean by not disturbing the position of the newspapers. This elevation of a task, that was usually considered to be women’s work, was instrumental in Arte Povera’s attempt at recalibrating the concept of what fine art stood for.

Untitled (Sculpture That Eats) (1968) by Giovanni Anselmo

Italian artist and sculptor Giovanni Anselmo was another prominent member of the Arte Povera movement. His artworks typically represented the relationship that exists between nature and time, with Anselmo making use of a variety of materials to adequately represent this juxtaposition. His most famous Arte Povera artwork ever made was Untitled (Sculpture That Eats), which was created in 1968. Consisting of two solid blocks of granite, a head of lettuce is seen between the two pieces, which are tied together with a copper wire.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ua11Yd2qRJI

The temporality of time is represented through the head of lettuce within Untitled (Sculpture That Eats) because if the lettuce dried out, the smaller block upon which it rested would collapse. Due to this, the sculpture had to be regularly looked after with new lettuce heads so as to maintain its structure and integrity as an artwork.

This necessity to preserve the sculpture through constant refreshments of its natural element demonstrated Anselmo’s interest in the impact that nature can have on inanimate objects.

Thus, Untitled (Sculpture That Eats) existed only for as long as the lettuce could support the structure. Through using a vegetable whose unavoidable destiny was to perish, Anselmo was able to effortlessly combine organic and inorganic materials to their point of breaking. The choice to use a lettuce head was also well thought out, with Anselmo implying the mastery that nature has over human construction, as demonstrated by the ability of tree roots to weaken foundations and brickwork over time.

The Legacy of Arte Povera

When this unique and confusing art movement first arrived on the scene, many wondered the question: what is Arte Povera? Over the years, the Arte Povera movement steadily grew in popularity, with some truly iconic artworks emerging from this moment in art history. However, the style proved to be quite short-lived and began to lose momentum, before it dissolved completely in the mid-1970s. This was partly due to the individual style of the Arte Povera artists emerging, which were slowly leading them off in different directions.

Despite this, the artists’ momentary solidarity and the work that Germano Celant put into expressing the aims, ideals, and concerns of Arte Povera art ensured that the movement had made its mark on art history. While Arte Povera faded into the background for several years following the 1970s, the importance of the movement was not completely acknowledged until decades later.

In the early 21st century, after reassessing the art from the 1960s, critics started to pay more deliberate attention to movements that occurred outside of the United States during that period, such as Arte Povera.

As an outcome of this shift, Arte Povera experienced something akin to a revival within the art world. Since then, the importance of the Arte Povera movement has been recognized, with critics citing the style as the precursor to some more modern approaches to sculpture that emerged, such as the Young British Artists group.

Since 2003, the market for Arte Povera art has increased consistently. A breakthrough moment occurred in February 2014, when an auction titled Eyes Wide Open: An Italian Vision was put on at Christie’s in London. This auction made up one of the biggest collections of Arte Povera works to ever be seen at this level of art, which saw 15 artist records being set in a single evening.

The Italian Arte Povera movement proved to be an exceptional style of art that emerged in the 1960s. The innovation brought on by this “poor art” movement went on to completely change the perspective of the art world and what it meant to create traditional works of art. Spurred on by the opportunity to challenge the contemporary art world, Arte Povera continually produced artworks that are still spoken about today. If you want to learn more about this unique style of Italian art, we encourage you to research further.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Arte Povera?

The name “Arte Povera” can be directly translated to mean “poor art”, although the word “poor” does not retain its traditional meaning. Instead, Arte Povera art is made out of a range of materials other than those used in traditional oil paintings and bronze or marble sculptures. The term itself was coined in 1967 by Italian art critic and curator Germano Celant.

Why Did the Arte Povera Movement Start?

The Arte Povera movement first began in Italy during the upheaval of the 1960s, during which many artists were creating artworks that took a political stance. These artists began to question and undermine the beliefs of the government and various other institutions.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Arte Povera – What Was the Arte Povera Movement?.” Art in Context. December 7, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/arte-povera/

Meyer, I. (2021, 7 December). Arte Povera – What Was the Arte Povera Movement?. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/arte-povera/

Meyer, Isabella. “Arte Povera – What Was the Arte Povera Movement?.” Art in Context, December 7, 2021. https://artincontext.org/arte-povera/.