Greek Art – Gems in Ancient Greek Art History

Greek art has remained a source of artistic inspiration since 650 BCE, which boasts many centuries’ worth of incredible developments in sculpture and pottery. From red-figure pottery to figurative vase paintings, the history of ancient Greek art is rich with cultural and socio-economic events that provide historians with vast insight into the life and art of Greek culture. In this article, we will explore the many unique gems of the Greek art world through the complex art forms of each art period in the ancient world. Read on for more about the history of Greek art and its many iconic contributions to art!

Table of Contents

A Little Bit About Hellas

Before we dive into the extensive history of ancient Greek art, let us explore the magnitude of the location with which we are engaging, namely, Greece. When we think of Greece, or Hellas, which it was previously known as, we immediately know more-or-less the impact that this ancient civilization had on shaping the art forms of many Western civilizations.

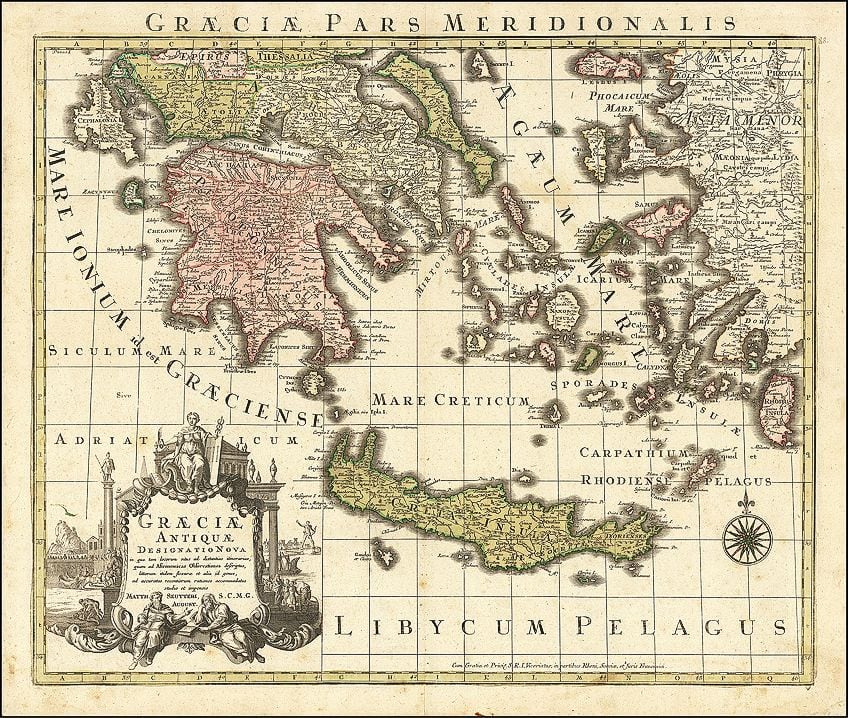

Greece is a bustling geographic hotspot on the world map, which is located in Southeast Europe. The country is divided into nine regions, namely the Aegean Islands, Central Greece, Crete, Epirus, Ionian Islands, Macedonia, Peloponnese, Thessaly, and Thrace. It is also located near to where Africa, Asia, and Europe converge and borders Albania, North Macedonia, Bulgaria, and Turkey.

The seas that surround Greece include the Aegean sea (this is towards the East of the mainland), the Ionian sea (towards the West), and the Cretan and Mediterranean seas (towards the South). There are also numerous islands surrounding Greece.

We also know the famous Mount Olympus, which is Greece’s highest mountain with Mytikas, its highest peak, at 9,570 feet. Olympus is worth noting as it holds an important place within Greek mythology, existing as the residence of the gods with Zeus on the throne. Greece is also widely considered as the “cradle” or “birthplace” of Western civilization and is recognized as the birthplace of various cultural and political doctrines such as democracy and philosophy. It also explored and developed various principles related to mathematics and science. In culture, it set the stage for drama, art, architecture, pottery, sculpture, and literature, and in sports, the Olympic Games, which is still ongoing in our present day and age.

Historical Foundations: What Are the Origins of Ancient Greece?

The best way to understand the historical foundations of ancient Greece is to look at its various periods throughout its development as a civilization, as there are numerous timeframes and stages of progression. Notably, Greece goes back all the way to prehistory with the Stone Age, which ended around 3,200 BCE, and then into the Bronze Age, which started around 3,200 BCE.

The Stone Age

The Stone Ages were divided into three distinct periods, namely, the earliest, Paleolithic, followed by the Mesolithic, and then the last, the Neolithic. During the Neolithic Greek Age (7000-3200BCE), there was an increased development of farming and stockbreeding, as well as new advances in architecture and various tools used.

The Neolithic Greek Age was further divided into six stages, namely, Aceramic (Pre-Pottery), Early Neolithic, Middle Neolithic, Late Neolithic I, Late Neolithic II, and Final Neolithic. With every micro-period within the Neolithic Age, there were new developments in farming and culture.

It is important to understand that these periods set the stage, so to say, for ancient Greek art.

It was during the early Neolithic period when people developed techniques to fire vases. The Middle Neolithic period brought with it new developments in architecture, namely the “megaroid”, also referred to as the “megaron”. This was a rectangular-shaped house with one bedroom and porches (open or closed), and it would also have columns at the front entrances.

The importance of the megaron structure is that it developed into the hall for Greek palaces. It is one of the primary characteristics of Greek architecture, also described as being “rectilinear” in shape. This would also become the shape for Greek temples.

Other architectural developments were the “Tsangli” structure, which was a settlement. This structure included two buttresses inside the house to add additional support for the roof. There were also rooms designated for different purposes. Houses during this period developed better foundations made of stone compared to the huts during the earlier stage. During the later Neolithic periods, there was an increase of advancements in farming and agriculture, and this period moved into the Bronze Age when people imported copper and bronze metals.

The Neolithic Greek Age occurred in various locations around Greece, namely, Athens, Dimini, Franchthi Cave, Knossos, Milos, Nea Nikomedeia, and Sesklo.

Into the Bronze Age of Greece – The Aegean Civilizations

The Greek Bronze Age is categorized by three dominant locations, and is also referred to as the Aegean Civilization, which was centered around the Aegean sea. The primary locations were, namely, the Cyclades, which are islands located southeast from the mainland of Greece, Crete, which lies more south of the mainland of Greece, and then there is the Greek mainland.

Each geographic area had different cultures. The Cycladic civilization (c. 3300-2000 BCE) from the Cyclades, the Minoan civilization (c. 2700-1100 BCE), which was from Crete, and the Mycenaean civilization (c. 3200-1050 BCE), which was from mainland Greece. The development of each civilization overlapped with the other, although the Mycenaean civilization eventually merged with the Minoan group.

Some of the notable features of these periods include writing, known as Linear A and Linear B, increased trade activities, and the development of various new tools.

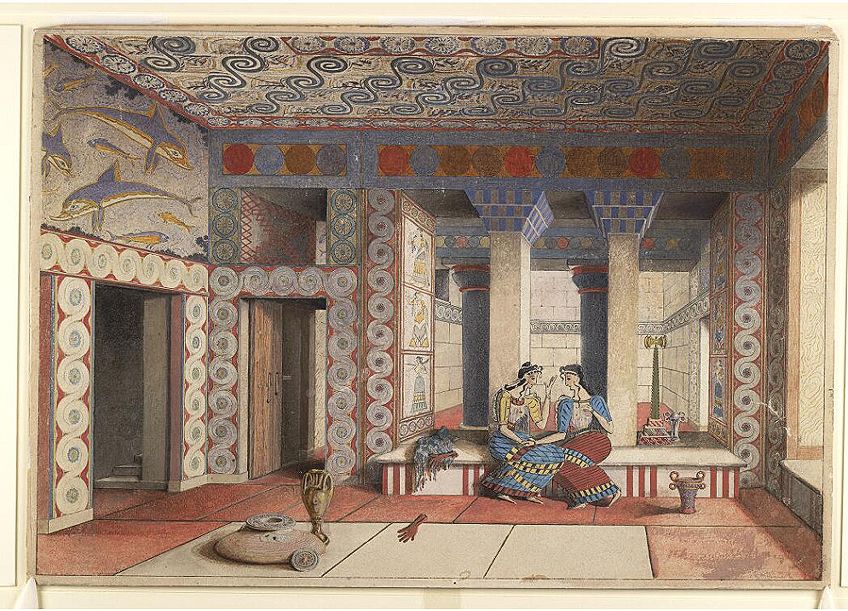

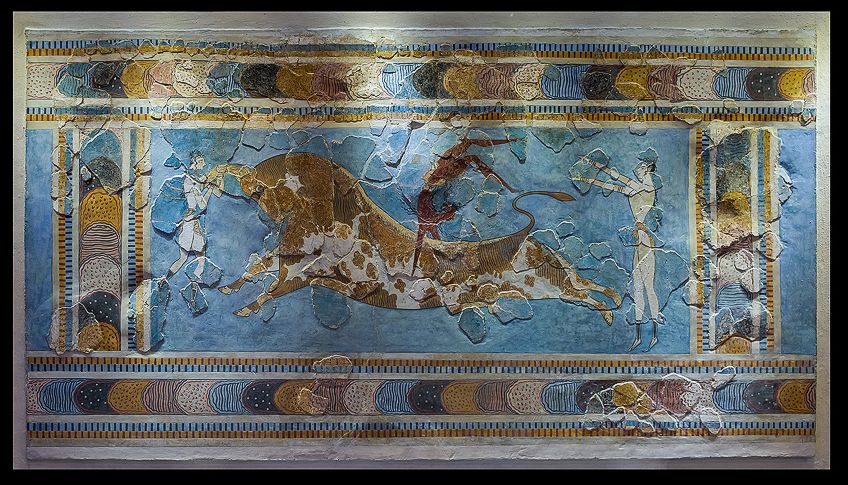

The Cyclades civilization created female figurines, or idols, fashioned out of marble. Many of these appear with large oval faces and elongated noses. The main sites for this civilization were Keros, Grotta, Phylakopi, and Syros. The Minoans were largely located at Knossos, and other areas like Malia, Phaistos, and Zakros. The Minoans are known for having provided the earliest foundations for European civilization and developed many advancements in writing and trade. Their art and architecture consisted of ancient Greek paintings called frescoes, which were brightly painted and featured subjects like animals from the land and sea, and natural landscapes. These were often painted inside the palaces with borders that featured decorative patterns, symbols, and popular motifs.

The Minoans also produced a wide variety of greek pottery and ceramics. Examples of the different shapes of vessels include the amphora (with three handles), various beakers, rounded vessels, and storage jars referred to as pithos. Ceremonial jugs were made to contain libations for rituals, and these were known as rhyta, and made in the shape of an animal’s head.

The bull was a significant animal in Minoan culture and they would often depict the bull’s horns in their art and decorations. The Minoans also had gold jewelry, sculptures, and palaces built to the height of up to four stories. Palaces were significant to the culture alongside their extensive architectural layouts, various farming communities, and roads built to connect the farms and villages.

The Mycenaean civilization was located mainly in Mycenae and other areas like Athens, Thebes, Pylos, and Sparta, among others. It is also referred to as the Helladic period since the Mycenaeans lived on mainland Greece and were considered indigenous.

Trading was common among the Mycenaean civilization, who exchanged goods and materials such as gold, glass, copper, and even ivory.

The Mycenaeans created artworks that were influenced by the Minoan civilization. They were known as having a strong warrior culture with the Trojan War as a famous event that popularized Greek culture. When we look at Mycenaean frescoes, one can spot a variety of scenes relating to battle, animals, nature, and warriors marching with their weapons. The similarities between Mycenaean art and Minoan art are often noted, although Mycenaean art is described as appearing more geometric and formal in its style. However, trade between Crete (Minoans) and Mycenae, also influenced the styles of art and its development between the two cultures.

The well-known Lion Gate (c. 1250 BCE) is one of the lasting remnants of an architectural relief sculpture, depicting two lions (or lionesses) facing one another, standing on their hind legs with their front legs resting on a block-like base, and a column in the center. The Lion Gate is located at the main entrance to the Acropolis, where the palace and citadel were once situated.

The Greek Dark Ages and the Start of Greek Civilization

The Mycenaean civilization ended around 1100 BCE, with the fall of this civilization and many others around that period becoming a widely debated topic. Many sources point to invasions by the Dorian civilization, climate change, natural disasters, and other social issues such as famine and overpopulation. This era is referred to as the “Late Bronze Age Collapse”, which would eventually become what is known as the Greek Dark Ages. This period occurred between 1100 BCE and 750 BCE, and was referred to as the “Homeric” period, which related to two of Homer’s poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Almost congruent with the above-mentioned periods, the Geometric period (900-700 BCE) occurred near the end of the Greek Dark Ages, and in the context of style, art on pottery was depicted in geometric shapes, which gave this period its name. It was after this period that Greece started to rapidly develop and transform.

Following this era, there was an increase in population and ancient Greek art began to take shape, embodying the ideals of Classical art as we now know it.

Greek Art and Architecture Characteristics

When we look at Greek art, we think in terms of idealized marble sculptures and human figures that appear as perfect and beautiful. There were three distinct periods in Greek art that characterized its development. Below, we look at these three periods along with their corresponding contributions to different art forms and notable artists within each period.

The Archaic Period (c. 650 – 480 BCE)

The Archaic period occurred with the onset of the Greek Olympic games in 776 BCE, and saw many political and social developments. Greek became a city-state, referred to as polis, which means “city” in Greek. These poleis were mainly ruled under tyranny, although there is also a debate that this tyrannical rule was not the same as what it turned into in later years. Tyrants essentially assisted communities to become more expansive in wealth and offered people more employment opportunities.

Art during the Archaic period is described as more naturalistic in its portrayal compared to the Geometric period. Some of the primary forms of artwork were pottery, painting, sculpture, and architecture. Because of trade between various Eastern countries, there was a wide Oriental influence noticeable on vases and vessels. Animals such as lions, griffins, and sphinxes were incorporated in Greek art and artists employed decorative motifs like curves and floral patterns.

The human form was also depicted not only in pottery paintings but also in sculpture. This was evident in the various life-sized figure sculptures created from stone. While there were elements of Realism in their portrayal, there was also an idealism largely influenced by the Mycenaeans and the show of strength and physical prowess in representations of the masculine form.

This was largely displayed in the figures of athletes and warriors of the time, marking the Mycenaean culture as a “Golden Age” for representations of bravery and heroism.

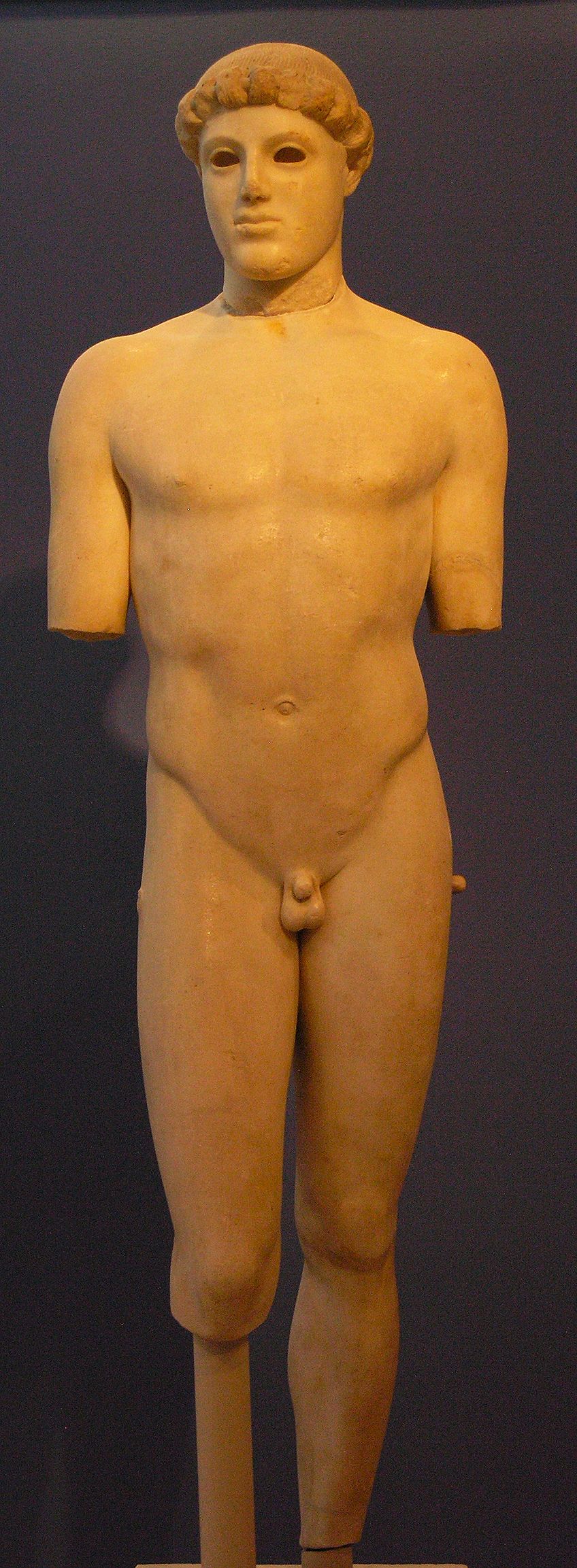

The human form in sculpture during the Archaic period was captured in kouros (“young boy”) and kore (“young girl”) statues. These statues were created in a “frontal” stance, bearing influence from Egyptian statues at the time, as well as being “freestanding”. The features that characterize them include an upright stance with arms at the sides, feet closely next to the other, and broad shoulders.

The female counterpart, the kore, was often depicted wearing dresses of their time with various stylistic elements. In both types of statues, we see what is referred to as the “archaic smile”, which gives the appearance of softness and serenity for both male and female statues. Furthermore, the purpose for these statues varied, for example, the korai were used as votive offerings to Greek goddesses like Athena. The kouroi were used as memorials to either deceased individuals or given to winners of games played and competed in.

There are numerous reasons why these statues were used since some believe that they were created resemble Greek deities and represented the God Apollo.

Examples of Greek sculptors and Athenian arts during this period include the Athenian Kritios, who worked in the later stages of the Archaic period. He is considered to have greatly influenced the more realistic artistic styles in sculpture in the subsequent Classical period. He is known as being the student of the sculptor named Antenor (c. 540-500 BCE), who created The Tyrranicides (510 BCE).

Tyrranicides was commissioned by Cleisthenes, a political leader who set the foundations for democracy in Athens during the 6th century BCE. He was remembered as the founder of Athenian democracy. The sculpture depicts the two figures, Harmodius and Aristogeiton, who assassinated the tyrant Hipparchus. Kritios recreated this sculpture with another sculptor called Nesiotes after it was taken by Xerxes I during the war between Persia and Greece. Kritios is also famous for his sculpture named Kritios Boy (c. 490-480 BCE). In size, it is recorded as being smaller than a life-sized sculpture.

As an early Classical period piece, Kritios showed Greek sculptors a new manner in depicting the human figure. We also see this technique commonly utilized in Renaissance and Neoclassical paintings and sculpture, and is referred to as contrapposto, the Kritios Boy is standing with his weight on one leg, giving the body a slight S-curve. Other features of this work show the dropped left shoulder, the expanded rib cage as a sign of inhalation, and the facial expression, which is not as idealized as we see in previous early Archaic sculptures.

Kritios is described as producing work that was more “severe” in style. This is exemplified in the figure’s mouth since it is not the Archaic smile we see in the idealized expressions before, but appears more grim and serious.

This statue is now housed in the Acropolis Museum in Athens with many other Athenian arts. The statue was one of many other ancient Greek artifacts found in the “Persian Rubble”, called Perserschutt, left behind by the Persian invaders after they sacked the Acropolis during 480 BCE. Of important debate today, is the removal of the Elgin Marbles, which were taken from the Parthenon in the 19th century and stored in the British Museum.

Classical Period (c. 480 – 323 BCE)

Where the Archaic period is often described as being experimental in its portrayal of Realism in the human form, the Classical period was a considerable advancement forward, depicting a Naturalism in the human form. This period in Greece was also considered the “Golden Age” because of the Greeks’ victory over Persia, which is known as the Greco-Persian War. This new period of peace and victory gave birth to many new developments in not only arts and architecture, but philosophy (with some of the greatest philosophers of Western history, namely, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle), science, and politics. The city-state of Athens was also rebuilt after the war.

The “Golden Age” lasted for around 50 years until the Peloponnesian War in 431 BCE, when Sparta won power over Athens. However, the Macedonian war then took over the Greek states, under the rule of King Philip II and then his son, Alexander the Great. The philosophies of Plato and Aristotle had a profound effect on Greek artwork and how Greek artists depicted the human figure. Plato also started an academy in Athens (c.387 BCE). This ushered in new ways of thinking, making reason and knowledge an important determining factor that underpinned many beliefs and perspectives. Many images of Greek figures can be found on black-figure and red-figure pottery, as well as in the works of Skopas and Lysippos.

Classical Greek Sculpture

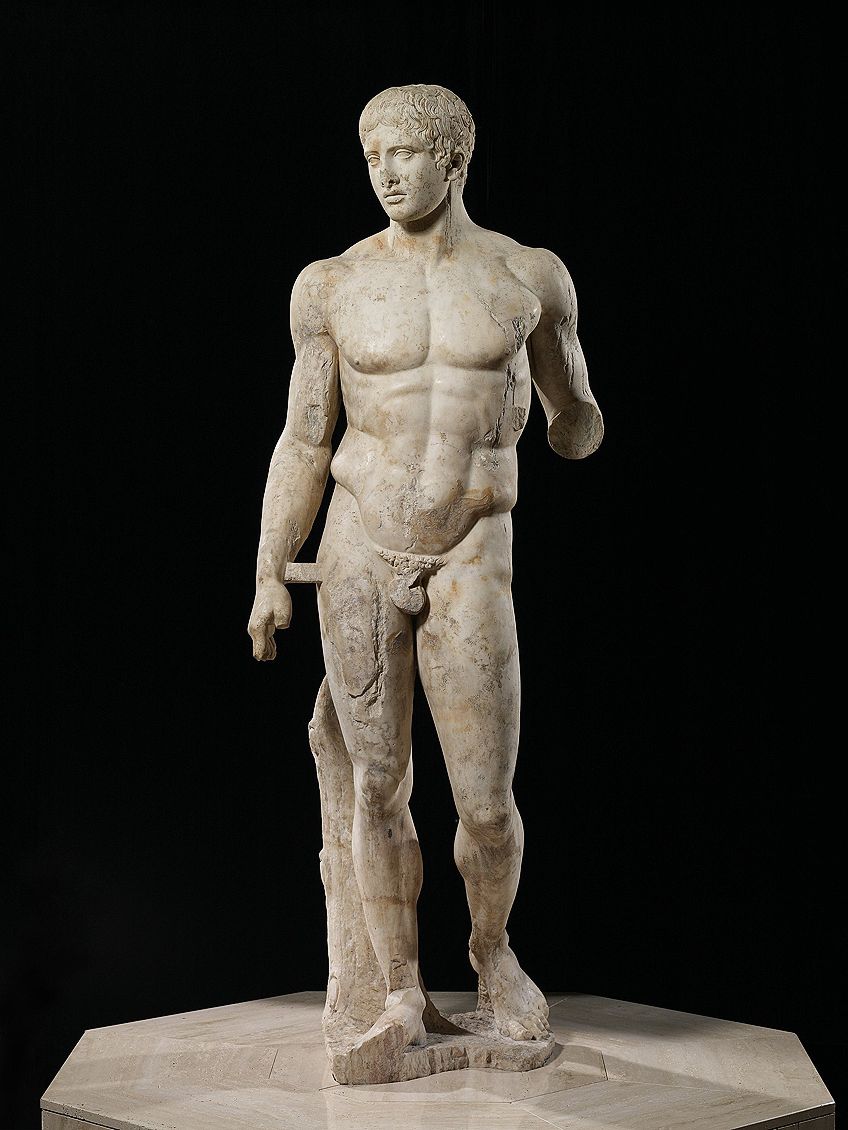

In Classical Greece, art became a representation of the natural world. Greek artists began to create sculptures that appeared human-like and detailed but still beautiful and perfect in their rendering. This brings us to what was known as the “Canon of Proportions”. This term refers to the “perfect” artwork, according to Greek sculptor Polykleitos. He developed what was termed The Canon (c. 450 BCE), which referred to a set of ratios based on mathematical measurements of the human body to depict each body part in perfect order and symmetry, commonly understood as a set of perfect proportions.

An example of this can be seen in his sculpture Doryphoros (c. 440 BCE), also known as the Spear Bearer, which depicts a nude male warrior. This work has been reproduced in marble by other sculptors due to the original bronze sculpture being lost. However, the replicas indicate the ideal perfection of the male form obtained through mathematical measurements.

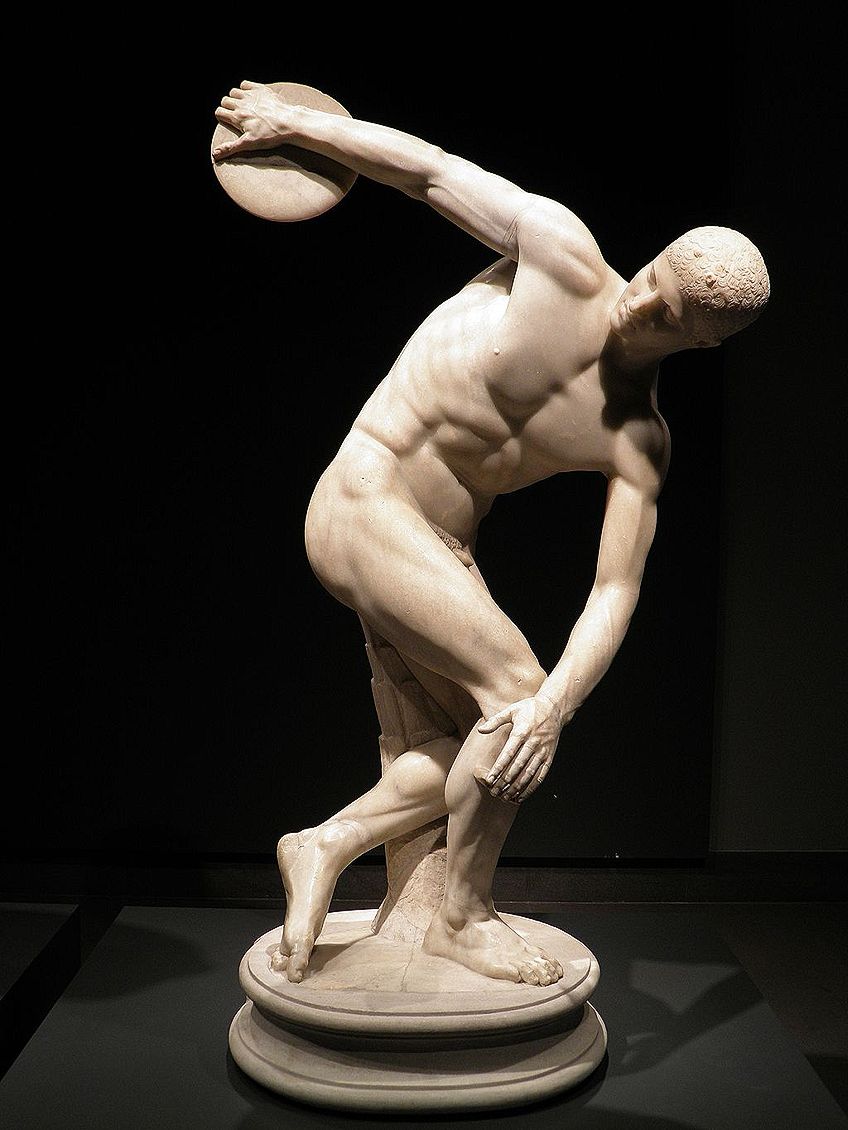

This sculpture was also a physical example of Polykleitos’ theoretical underpinnings about achieving perfect form through proportions, which ultimately sought to illustrate harmony and perfect balance. The word “Canon” means “rule” or “measure”. It was the interest in achieving and depicting the idealized human figure, which was usually sought in the figures of male athletes and warriors, that became widespread in Greek sculpture. We also see this element in the works of other Greek sculptors of the Classical period, such as Myron’s classic Discobolus or Discus Thrower (c. 425 BCE).

The Discobolus was originally sculpted in bronze but recreated by various Roman sculptors over time in bronze and marble. It is a male discus thrower portrayed in the act of throwing the discus. His body appears contorted to prepare for the throw, putting him in the classical contrapposto stance. We see his right arm behind him holding the discus, and his head is turned in the same direction. At any moment, we expect the arm to swing forward. This image creates a sense of Naturalism in the human figure and displays each body part in correlation with the other.

Praxiteles was another prominent sculptor of the 4th century BCE, famous for his life-sized female nude sculptures, of which he was a pioneer. One of his popular sculptures includes Aphrodite of Cnidus (c. 4th century BCE), depicting the nude female holding a bath towel in her left hand (or reaching for one), while covering her genitalia with her right hand, and represented with her breasts exposed.

A sculpture such as this was revolutionary at the time because all sculptures were typically representative of male nudes. Additionally, sculpting the Greek goddess as life-sized created further impact, and it was clear that Praxiteles had set the tone for Greek sculpture in a daring new way. His Aphrodite was also described by the famous Roman author, Pliny the Elder, as one of the finest sculptures made.

Classical Greek Architecture

The grandeur of Classical Greek architecture is captured in the walls of the famous Greek temple, the Parthenon (447-432 BCE). It is a large rectangular structure located on the Acropolis of Athens, which is a flat hill overlooking the city. It was designed by architects Ictinus and Callicrates and dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena.

A monumental sculpture was housed in the center of the temple, titled Athena Parthenos. It was created by a well-known Greek sculptor, Phidias. The sculpture was an example of the majesty of Athena and was around 40 feet in height and made from ivory and gold (the goddess’ skin was sculpted in ivory and her clothes were made from gold fabric).

The Parthenon had numerous other sculptures and friezes surrounding it, including 17 Doric order columns along the longer horizontal sides and eight along the shorter sides. The Doric order columns were a testament to another architectural development within this period, namely the Doric and Ionic column styles. The latter, Ionic style, was also prominent in the Hellenistic period, from which the third, Corinthian style, also emerged.

As the first evolution of the architectural “orders”, the Doric style is plainer and described as “austere”. It consists of the top of the column, known as the “capital”, which is not decorated but created in plain stone. The base rests without support on the stylobate, which is the upper step on a temple’s crepidoma (the leveled or tiered foundation that holds the superstructure). The difference between the Ionic style is that the capital is more stylized and decorated, and is often described as being more slender in appearance than the robust Doric style. The Ionic column also includes a base to support it.

The Hellenistic Period (c. 323 – 27 BCE)

While the Classical Period is marked by being under the rule of Philip II of Macedonia, near the end of this period, King Philip II was assassinated and replaced by his son, Alexander the Great. The Hellenistic period, or Hellenism, came into effect after the death of Alexander in 323 BCE. However, since Alexander did not have a successor, there was a period of uncertainty between all the generals. This uncertainty led Alexander’s generals to ascertain their power in different dynasties, however, the Roman Republic eventually took over Macedonia in 146 BCE, and by 27 BCE, Emperor Augustus took over Greece and it became part of the Roman Empire.

The Romans were inspired by Greek art and architecture since numerous replicas in marble have been found to have originated from original works created by Greek artists.

During the Hellenistic period, Greek art became more diverse with a wider range of subjects, including not only young or warrior-like males but everyday folk and animals. Greek artists also moved away from depicting idealized forms, as there was a heightened tendency toward Naturalism, almost to the point of being dramatic across sculpture and painting. Art was also commissioned by patrons and created as decorative additions to homes, such as bronze statues.

Hellenistic Greek Sculpture

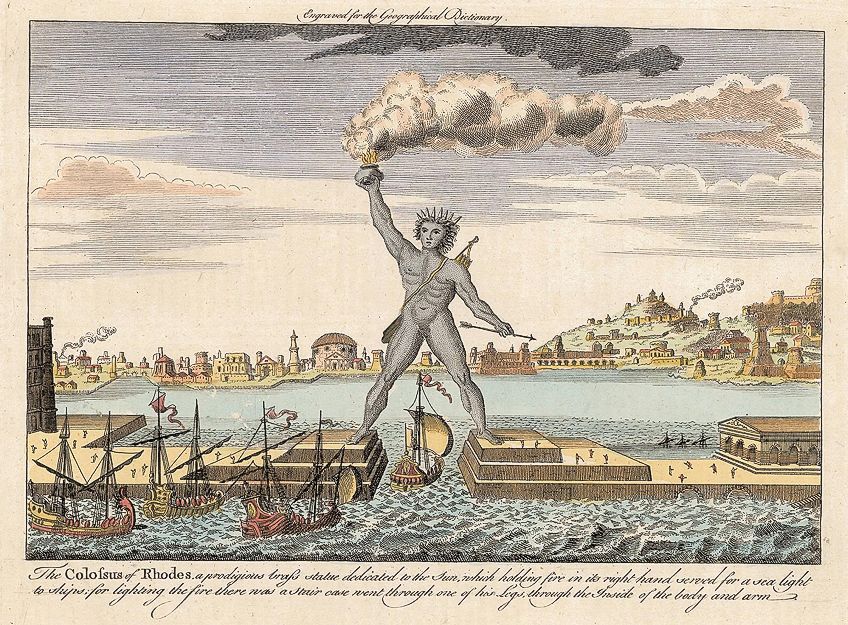

Greek sculptures appeared more emotive during this period. Considering the rigidity and idealism of the “archaic smile” from the preceding periods, there has been considerable evolution in depicting the human form. There was a focus on drama and emotion, with this period often described as being more pro-theatrical in art and architecture. Many famous sculptures were created in Hellenistic Greece, including the Colossus of Rhodes (c. 220 BCE) by Chares of Lindos, which was around 110 feet in height. This magnificent statue was a male figure dedicated to Helios, the sun God. Unfortunately, this statue was destroyed during an earthquake.

Another sculpture was The Dying Gaul (c. 230-220 BCE) by Epigonus. This depicted a typical example of the expressive nature of Hellenistic sculptures. The figure was of a Gaul, as was evident from his haircut and the ring around his neck, otherwise referred to as a “torque”. He appears caught in the process of dying, which is shown in his posture and broken sword next to him. What makes this sculpture so unique is that it captures a moment of death, inevitably evoking emotions in the viewer that stir the feelings of defeat and hopelessness.

Other notable sculptures include the famous Venus de Milo (130-100 BCE) by Alexandros of Antioch. Here, we see a female figure (missing both arms), supposedly Venus, the Greek goddess of love. However, various scholarly debates suggest it could either be a prostitute or the sea goddess, Amphitrite, since the statue was found on the volcanic island of Milos in 1820.

We will notice the familiar contrapposto posture in this sculpture, which was made evident by the draping of her robe around her lower torso and elevated left leg. There is also a hint of sensuality with her exposed upper torso and the robe that appears to slide off her legs. There is also a dramatic element to how she was posed, again, attracting attention from onlookers.

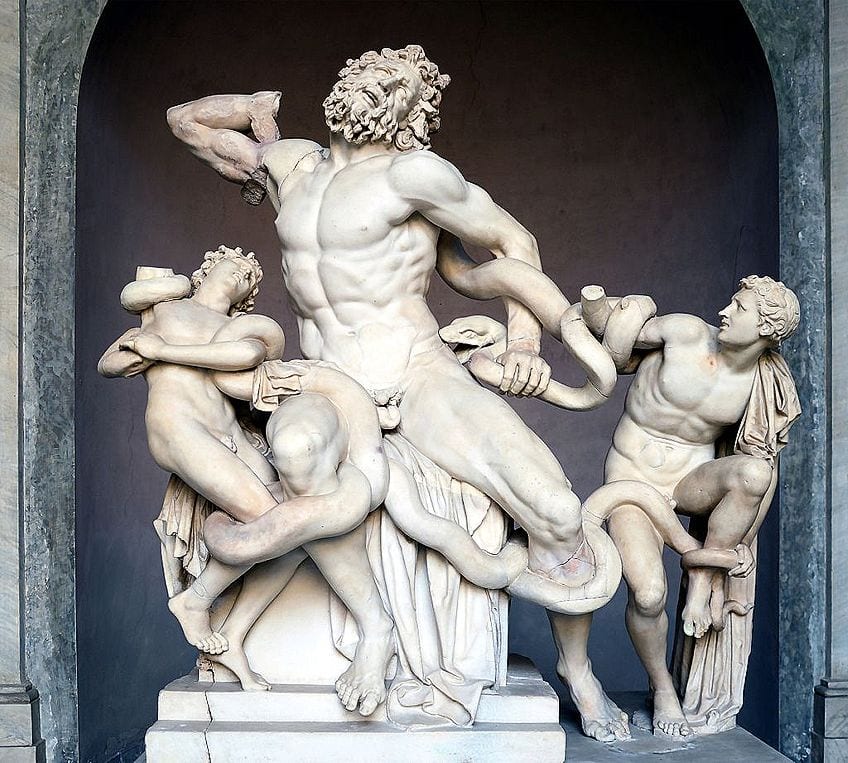

This heightened sense of drama in one of the most famous sculptures today from the Hellenistic period can also be seen in Laocoön and His Sons (27 BCE-68 CE), which was created by three sculptors from Rhodes, namely, Agesandro, Athendoros, and Polydoros. This piece was excavated in 1506 in a vineyard in Rome, with Michelangelo supervising the process. After its excavation, it was taken to the Vatican and put on display in the Belvedere Court Garden. This sculpture has been the model for many artists during the Renaissance period and inspired many other modern artists hundreds of years later.

It is described as one of the most studied and replicated pieces of Greek art.

The subject represents Laocoön in the center with his two sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus, in a desperate struggle to pry the biting sea serpents off them. We notice how Laocoön himself is being bitten by one of the serpents and his son to the left has fallen over, possibly already killed. This sculpture catches the moment of death and struggle of the three figures, increasing the intensity of emotion and dramatic effect. Added to this is the larger-than-life size of Laocoön’s body. The narrative was inspired by the legend of the Trojan War, where Laocoön (who was a priest) was said to have given a warning to the Trojans about the wooden horse and their plans. As a result, he was attacked by serpents in an effort to silence him.

Hellenistic Greek Architecture

In Hellenistic architecture, the Corinthian order soared in popularity and was a more elaborate style that brought a decorative effect to buildings. Architecture in this period was adapted to accommodate more people for entertainment purposes. An example of this new development includes the Pergamon Acropolis. Designed as a cultural hub, this acropolis featured theaters, baths, libraries, gymnasiums, and religious buildings such as temples. It truly became a testament to a new, urbanized way of life.

Another architectural element of this acropolis includes the Altar of Zeus (Pergamon Altar), which was over 30 meters in width. It was created in the shape of an upside-down “U”, with steps comprising most of its width in the center. Throughout the superstructure were numerous columns in the Ionic style. Along the base of the superstructure was the Gigantomachy frieze, which depicted the mythological story about the battle between the Greek Olympian Gods and the giants.

The frieze measured over 100 meters in length and was sculpted in a high-relief method. The sculpted scenes are dynamic in their portrayal and move along each of the altar’s sides. Some figures also appear to continue onto the staircase from the frieze, as we see in their legs and feet, seemingly becoming a part of the whole structure instead of being relegated to remain along the structure’s sides.

Pergamon was a city ruled by the Attalid dynasty, and the creation of the Pergamon Acropolis was to establish the Kingdom of Pergamon as part of Greece after Alexander the Great’s demise. The Pergamon Dynasty emerged at a later stage than other dynasties during this time, and this cultural hub was a testament to their part in the Greek inheritances.

To Rome and Beyond

While there are many other structures and sculptures from the Hellenistic period, this period eventually evolved into the rule of the Roman Empire. The Pergamon Kingdom, under the rule of King Attalus III, was taken over by the Roman Republic after the King’s death in 133 BCE.

It is said the Roman Republic began around 509 BCE, when the last king (of which there were seven), Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, was overthrown by his nephew Lucius Junius Brutus, who was known as one of the first founders of the Roman Republic. The Roman Republic eventually developed into an empire in around 27 BCE, with Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (Augustus) as the first emperor. Greek artwork was greatly admired and copied by the Romans, and its classical essence of rationality, beauty, and proportion lived on through their art and architecture. Beyond Rome, the Greek art style was given a second breath, so to say, through the eyes, hands, and minds of Renaissance painters and sculptors.

To this day, we are still touched by the beauty and symmetry left behind in what remains of ancient Greek artifacts. While most of the Greek art has since been lost or destroyed, it is remembered and immortalized by those who were inspired by the ancient art styles many centuries ago. We hope that these incredible gems of Greek art history will enlighten you, as you continue to learn about the many important artistic developments of the past.

Take a look at our Ancient Greece art webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Were the Different Periods in Greek Art?

Greek art has a long history that dates back to prehistoric times. However, the Classical Greek era is divided into three primary stages of development, namely, the Archaic period (c. 650-480 BCE), the Classical period (c. 480-323 BCE), and the Hellenistic period (c. 323-27 BCE). These three eras are considered to be the most important periods in Greek art.

What Does Classical Order Mean in Greek Art?

The term Classical order is used to describe a type of column style used in ancient Greek architecture. There were three dominant orders, namely, Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian. The Doric order style was simple in its design, while the Ionic and Corinthian orders were decorative, elaborate, and more slender in appearance than the shorter Doric order.

What Are Some Greek Art Characteristics?

Greek art was characterized by many qualities. These include the depiction of beauty in an idealized manner. Figures in sculpture became more naturalistic in their portrayal of proportion and balance. The famous contrapposto technique became widely incorporated, adding a new element of dynamism to the representation of the human figure. Greek art depicted the belief in mathematical congruency to determine beauty. Greek art included the use of materials such as clay, terracotta, bronze, stone, and miniature works created in ivory, metal, and bone.

Which Museum Has the Largest Collection of Greek Art?

The National Archaeological Museum is considered to have the largest collection of Greek artifacts, with more than 11,000 works from prehistory to antiquity. The museum is also said to have the highest number of Greek statues and is recognized as the largest Greek museum.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Greek Art – Gems in Ancient Greek Art History.” Art in Context. May 19, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/greek-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 19 May). Greek Art – Gems in Ancient Greek Art History. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/greek-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Greek Art – Gems in Ancient Greek Art History.” Art in Context, May 19, 2021. https://artincontext.org/greek-art/.