Claude Monet – The Impetus for Impressionism

Claude Monet’s paintings deviated from the accepted art of the time’s unambiguous representation of shapes and linear perspectives, and instead explored free handling, strong color, and stunningly unorthodox arrangements. In each scenario of his impressionist paintings, the focus of Claude Monet’s artwork switched from depicting humans to expressing distinct aspects of lighting and mood. Monet the artist grew increasingly attuned to the ornamental elements of hue and shape in his final years.

Table of Contents

Claude Monet’s Biography

| Date Born | 14 November 1840 |

| Date Died | 5 December 1926 |

| Place Born | Giverny, France |

| Associated Movements | Impressionism |

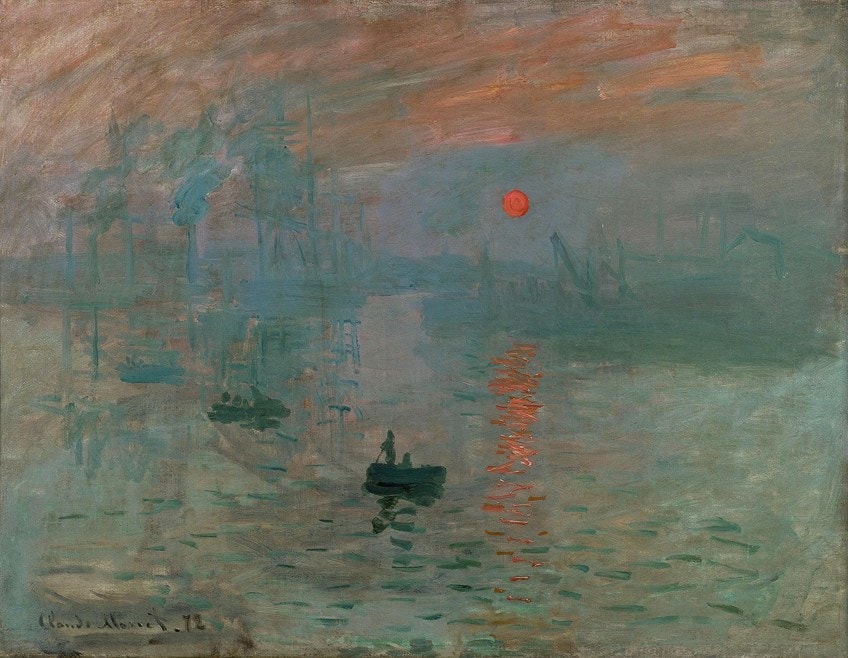

Claude Monet the artist was the head of the French Impressionist era, and he practically gave the group its title. He was instrumental in drawing its believers together as an inspiring personality and presence. Monet was keen on working outside and catching natural light – as can be observed in one of Monet’s famous paintings, Impression, Sunrise (1872).

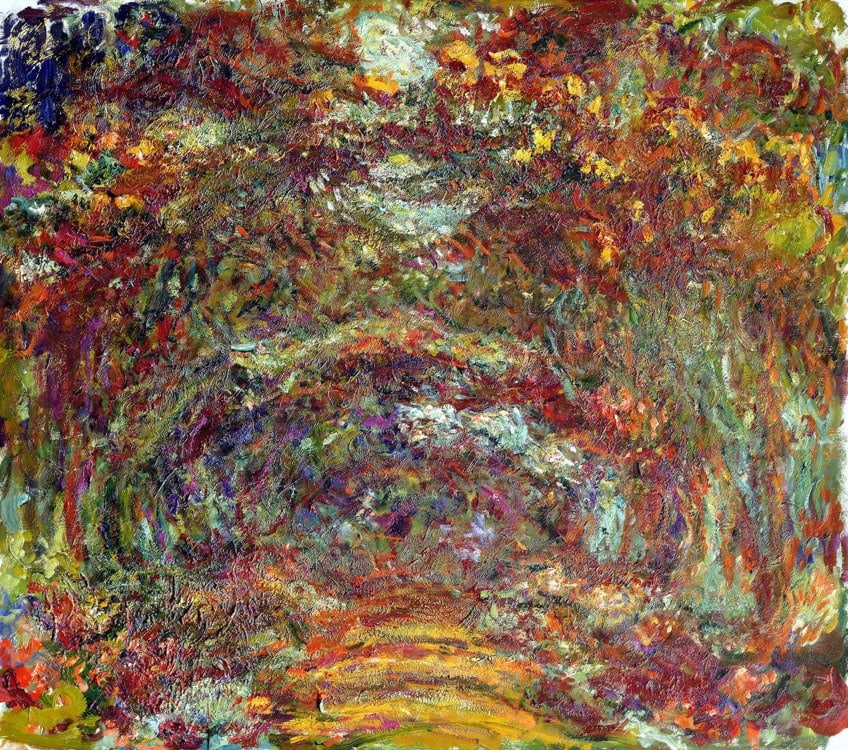

He would eventually raise the method to one of its most renowned cornerstones with his series works, in which his impressions of the same subject, viewed at distinct intervals of the day, were caught in several series, such as Monet’s garden paintings. Claude Monet’s artwork from his later years frequently acquired stunning levels of abstraction, and this has promoted him to successive generations of abstract artists.

Early Life of Claude Monet

Claude Oscar Monet was born on the 14th of November 6, 1840, in Paris and relocated to Le Havre, a town on the coastline in the northern part of France when he was five years old. His father was a successful shopkeeper who eventually became a shipper. His mother passed away when he was 5 years old. The waters and rugged coastlines of Northern France had an early impact on him, and he would often not attend classes to go on hikes along the bluffs and dunes.

He learned to draw as a child at the College du Havre from a recent student of the famed Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David. From a young age, he was a very artistic and business-savvy young man, drawing caricature portraits in his spare time and putting them up for sale for 20 francs apiece.

He was able to save a significant amount of money from his painting sales by focusing on his early talent for art.

The Career of Monet the Artist

Claude Monet was an artist from France and the pioneer of impressionist paintings. He is regarded as a significant predecessor to modernism, particularly in his efforts to represent nature as he saw it. Throughout his lengthy career, he was the most continuous and prominent exponent of impressionism’s theory of conveying one’s feelings as being more important than the accurate depiction of nature as applied to outdoor landscape painting. The name “Impressionism” comes from the name of his work, Impression, Sunrise (1872).

Early Training

In 1856, Monet met Eugéne Boudin, a landscape painter known for his landscapes of northern French seaside villages. This was a watershed moment for Monet. Boudin urged Monet to create outside, and the en plein air approach changed his feelings about how art might be generated:

“It was like a curtain had been pulled from over my eyes; I had come to realize. I understood what art might be.”

Despite being turned down for a grant, Monet traveled to Paris to learn in 1859, with the aid of his family. Rather than following the more traditional route of a Salon artist and registering at the École des Beaux-Arts, Monet entered the much more avant-garde Académie Suisse, whereupon he met artist Camille Pissarro.

Mature Period

Monet was obligated to serve his time in the army and was sent to Algiers in 1861. The ambiance in Northern Africa inspired Monet and greatly influenced his artistic and personal viewpoint. When he returned to Le Havre after his duty, the Dutch landscape and marine painter Johan Jongkind delivered him “last schooling of the eye.”

Following this period, he once again returned to Paris, where he apprenticed in Swiss artist Charles Gleyre’s workshop, with pupils – and future Impressionists – such as Alfred Sisley, Frédéric Bazille, and Renoir. The Paris Salon selected two of Monet’s seascapes for display in 1865, Mouth of the Seine at Honfleur (1865) and Le pavé de Chailly (1865).

Nevertheless, the artist felt constrained by painting in a workshop and preferred his previous experiences of creating in nature, so he relocated just outside of Paris to the border of the Fontainebleau woodland. His boldly enormous Woman in the Garden (1867) was a confluence of the ideas and themes in his earlier material, using his future bride, Camille Doncieux, as his single model. Monet had been hoping that the artwork would receive positive feedback at the Paris Salon, but his manner put him in conflict with the judges, and the image was turned down, rendering Monet distraught. At the time, the formal salon still admired Romanticism.

To make up for the 50-year-old offense, Monet forced the French government to acquire the artwork in 1921 for the staggering cost of 200,000 francs.

Monet believed that London would provide safety from the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, creating iconic images such as The Thames Below Westminster (1871). His wife and their newborn child accompanied him. He went to museums in London and viewed paintings by J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, whose romantic realism definitely affected his use of light. Most crucially, he met Paul Durand-Ruel, the owner of a fledgling Bond Street modern art gallery. Durand-Ruel was a staunch admirer of Pissarro and Monet, as well as Degas, Renoir, and other French Impressionists.

Monet once again made his way back to France after the war and resided in Argenteuil, a Paris neighborhood near the Seine River. Over the course of the next six years, he polished his technique and produced over 150 canvases to capture the changes in the burgeoning region, such as Le bassin d’Argenteuil (1872).

His appearance drew the attention of Parisian friends like Manet and Renoir.

While Manet was ten years older and had distinguished himself as a painter considerably earlier than Monet, by the 1870s, both had significantly affected the other, and Monet had effectively won Manet over to creating art outdoors by 1874. In order to continue their protest against the salon system, Monet and his associates staged their own exhibition in 1874, which was exhibited in the abandoned studio of photographer and caricaturist Nadar.

This was dubbed the “First Impressionist Exhibition.” These painters, including Degas, Renoir, and Pissarro, were among the first to adapt to changes in their city as a group. The broader boulevards required to suit the rising trends of public life and the burgeoning flow of consumption reflected Paris’ modernization. Monet unwittingly gave the movement its name with his 1873 piece Impression, Sunrise, albeit that phrase was first used by authors to condemn these sorts of works.

While Monet the artist was raised in a middle-class family, his lavish lifestyle resulted in him spending most of his life in various stages of debt and hardship.

Claude Monet’s artworks were not a reliable source of income for him, and he frequently had to borrow funds from friends. Monet experienced some economic security after winning many commissions all through the 1870s, but he was in severe problems by the close of the decade. In 1877, the Monets were living in Vetheuil with Alice Hoschede along with her half-dozen children.

The Hoschedes were close acquaintances and supporters of Monet’s artwork, but the struggling husband’s business ended up failing, and he was forced to leave his family.

Consequently, Monet needed to find a low-cost home for his rather big family. In 1878, Camille went into labor with another son, Michel. When Camille passed a year later, Monet’s paintings changed, concentrating more on the flow of experiencing time and the moderating influences of environment and character on the subject matter, such as Floating Ice on the Seine (1880).

Alice remained with Monet and married him for the second time in 1892. Monet was seeking a home for Alice and their eight children in 1883. He found a home in the peaceful little region known as Giverny, which had a tiny population of around 300 residents. He was very attracted to a home that he was able to rent until purchasing (and significantly expanding) in 1890. Monet’s principal source of inspiration for the last 30 years of his life was the Giverny estate. He created a Japanese garden for reflection and relaxation, complete with a pond laden with water lilies and an arching bridge.

He was famed for saying: “My garden is my most exquisite work of art. What I really need are flowers. Always. My heart will always be at Giverny, and perhaps it is because of the flowers that I became an artist.”

Monet achieved his greatest achievements at Giverny. His Impressionist paintings such as The Artist’s Garden at Giverny (1900) started to sell in the United States, England, and in his own country. He became a nobleman, hiring a big group of employees at his residence, which included six gardeners who cared for his lily pond and cherished garden.

Monet’s paintings were more interested in ambiance and surroundings than in modernism.

When his series of grain stacks, such as Wheatstacks (End of Summer) (1890-1891), created at varying periods of the day, was shown at Durand-gallery, Ruel’s it gained great accolades from critics, buyers, as well as the public at large. He subsequently changed his focus to Rouen Cathedral, where he researched the effects of shifting ambiance, lighting, and mood on its facade at various periods throughout the day.

As a consequence, dozens of paintings of dazzling, somewhat exaggerated hues were created, forming a visual archive of gathered perceptions.

Later Years and Death of the Artist

Monet chose to be alone with nature, creating, rather than engaging in philosophical or critical conflicts inside Paris’ creative and cultural environment. Having traveled during the 1880s and 1890s to locations such as Venice, London, Norway, and around France, he settled in Giverny for the rest of his lifetime in 1908. The artist’s second wife, Alice, died in 1911, and his son passed away the year after that. Monet almost completely stopped painting following these tragic events, the aftermath of World War I, and even the formation of a cyst over one of his eyes.

In that period, French leader Georges Clemenceau, who was also a friend of Monet’s, encouraged Monet to produce a work that would bring the country out of the melancholy of the Great War.

Monet first said he was too old and unfit for the assignment, but Clemenceau gradually pulled him out of his grief by urging him to make a wonderful artwork – what Monet referred to as Grandes Décorations, better known as the Water Lilies of the Musée de l’Orangerie (1927). As a realm within a universe, Monet pictured a continual sequence of waterscapes set in an oval salon. For this reason, a new workshop with a glass wall overlooking the garden was created, and notwithstanding having cataracts, Monet the artist was able to maneuver a movable easel around the room to catch the ever-changing lighting and viewpoint of his flowers.

The Orangerie museum eventually had two elliptical chambers created to house Monet’s paintings of the water lilies. The all-over designs of the works and the chambers gave the visitor the impression that they were afloat in the water, with flora surrounding them from every angle. Many commentators praised the end installation. Monet died of lung cancer on the 5th of December, 1926, aged 86, and was laid to rest at the Giverny church burial site. Monet insisted on keeping the celebration modest, so just approximately fifty people attended the ceremony.

In 1966 Michel gave Monet’s residence, gardens, and water lily ponds to the French Academy of Fine Arts.

Following the renovation, the home and grounds were offered to the public in 1980 through the Fondation Claude Monet. In combination with Monet mementos and other items from his life, the residence houses his gallery of Japanese woodcut prints. The home and gardens, as well as the Museum of Impressionism, are prominent features in Giverny, which attracts visitors from all over the world.

Claude Monet’s Legacy

Monet’s exceptionally long life and vast artistic production are commensurate with the magnitude of his present appeal. Impressionism, of which he is a cornerstone, remains one of the most popular creative movements, as proven by the vast mass consumption of diaries, cards, and banners. Of course, Monet’s paintings attract high valuations, and some are regarded as priceless; in fact, Monet’s art is housed in every major museum on the globe.

Despite the fact that his paintings have now been venerated, Monet was only recognized in a few groups of art aficionados for many years after his death.

The Abstract Expressionists gave his art a tremendous revival in New York. Monet’s huge paintings and semi-abstract, all-over compositions influenced artists such as Jackson Pollock and Rothko. Monet’s haystacks were also referenced by pop artists in works such as Andy Warhol’s recurring portraits. Likewise, several Minimalists adopted the same concept in their item serial presentation.

Indeed, Impressionism and Monet are today regarded as the foundation of all contemporary and current art and are thus fundamental to nearly any historical study.

Claude Monet’s Art Style and Method

Monet has been referred to as “the impetus for Impressionism.” Recognizing the influences of light on the local color of things, as well as the effects of color contrast, was critical to the Impressionist artists’ art. His loose manner and use of color have been regarded as “nearly ethereal” and the “exemplar of impressionist technique”.

“Impression, Sunrise” exemplifies the “basic” Impressionist idea of presenting just what is plainly visible.

Monet was interested in the effects of light, and he considered that his sole “worth rests in having worked directly in front of nature, attempting to convey my perceptions of the most transitory phenomena.” He frequently blended current life issues with outdoor light in order to “paint the air.”

Monet used light as the primary theme of his paintings. To capture its nuances, he would occasionally finish a painting in a single session, frequently without any preparation. He wanted to show how the light changed the color and the perspective of reality. His fascination with light and reflections started in the late 1860s and lasted the remainder of his life. During his first visit to London, he gained an appreciation for the link between the artist and motifs – what he called the “envelope.” He used pencil sketches to swiftly jot down ideas and themes for further reference.

Monet’s landscape paintings emphasized industrial aspects such as trains and factories, while his early seascapes depicted somber nature with muted colors and local folk.

Théodore Duret, a reviewer and Monet acquaintance, stated in 1874 that he was “little captivated by rural images. He was particularly pulled towards nature when it is adorned and towards metropolitan settings, and for choice, he portrayed floral gardens, parks, and groves.” When showing humans and landscapes together, Monet desired that the environment is not only a backdrop and that the figures not overwhelm the composition.

Monet chastised Renoir for disobeying Monet’s order to paint landscapes in this manner. He frequently represented suburbia and rural recreational activities in Paris and dabbled with still lifes as a youthful painter. From the 1870s on, he steadily drifted away from urbanized settings, depicting them only to deepen his study of light.

Modern scholars – and later researchers – believed that by presenting Belle Île, he was indicating a wish to move away from the sophisticated society of Impressionist paintings and towards raw nature. Following his encounter with Boudin, Monet committed himself to the pursuit of new and improved means of pictorial expression.

To that goal, as a young man, he went to the Salon and became acquainted with the works of older artists, as well as making acquaintances with other creative people.

The five years he stayed in Argenteuil, where he devoted much of his days in a modest floating workshop on the Seine River, were crucial in his investigation of the impact of light and reflections. He started thinking in terms of colors and forms instead of situations and objects. He employed vibrant colors in paint dabs, dots, and splodges.

After rejecting Gleyre’s studio’s academic lectures, he liberated himself from theory, declaring, “I prefer to paint as a bird sings.” Monet was influenced by Boudin, Courbet, Corot, and Jongkind, and he frequently worked in line with avant-garde aesthetic advances.

Monet looked at soot and steam and how they influenced color and transparency in a collection of works at St-Lazare Station in 1877, being often impenetrable or sometimes transparent.

He intended to utilize this research to portray the impacts of fog and rainfall on the landscape. The investigation of the influences of atmosphere would lead to a number of Monet’s famous paintings in which He portrayed the same subject (such as his water lily series) in varying illumination, at different times of day, and as the weather and seasons changed. This practice began in the 1880s and lasted until his death in 1926. Monet “transcended” the Impressionist style in his later career and began to push the frontiers of painting.

In the 1870s, Monet modified his palette, carefully avoiding deeper tones in favor of pastels, as can be observed in Woman with a Parasol (1875). This corresponded with his gentler style, in which he used smaller and more diversified brushwork.

His palette would alter again in the 1880s, with a greater focus on balance between warm and cool tones than before, as can be seen in Waterloo Bridge, London, at Dusk (1904). Following his optical procedure in 1923, Monet reverted to his earlier manner. He avoided flashy colors or “coarse treatment” in favor of blue-green color palettes.

While struggling from cataracts, his works became more expansive and abstract—from the late 1880s on, he reduced his arrangements and chose themes that could give a wide range of color and tone. He began to utilize more red and yellow tones after returning from his vacation to Venice.

The style shift was most likely an unintended consequence of the disease, rather than a deliberate choice.

Owing to the damage of his eyesight, Monet would frequently work on huge canvases, and by 1920, he stated that he had gotten too acclimated to wide painting to return to tiny canvases. The impact of his cataracts on his productivity has been debated among scholars who claim that the development of degeneration from the late 1860s onwards resulted in a loss of crisp lines. Gardens were a recurring theme in his work, becoming particularly important in his later work, especially in the last 19 years of his life. Daniel Wildenstein saw a “streamlined” continuity in his works, which he described as “enhanced by necessity”.

From the 1880s through the 1890s, Monet’s sequence of works of distinct topics tried to capture the many circumstances of light and climate. As the lighting and weather varied during the day, he alternated between paintings, sometimes painting on eight at once and spending an hour on each. In 1895, he displayed 20 paintings of Rouen Cathedral, depicting the façade in various lighting, weather, and atmospheric circumstances.

The paintings focus on the movement of lights and shadows across the surface of the enormous Medieval edifice, altering the solid stone. He dabbled with making his own frameworks for this series.

His first exhibition featured haystacks created from various perspectives and at various times of the day. In 1891, 15 of the works were shown at the Galerie Durand-Ruel. He created 26 views of Rouen Cathedral in 1892. Monet traveled to the Mediterranean between 1883 and 1908, capturing monuments, vistas, and coastlines, including a sequence of works in Venice. He created four series in London: The Houses of Parliament, London (1901), Charing Cross Bridge (1901), Views of Westminster Bridge (1871), and Waterloo Bridge (1903).

Helen Gardner has written, “Monet has created an unmatched and unrivaled record of the passage of time as seen in the flow of light across similar shapes.”

A List of Monet’s Famous Paintings

Claude Monet was famous for his Impressionist paintings. These works of art still inspire artists right up to the present day. We have created a list of some of his most renowned works.

- Women in the Garden (1867)

- Westminster Bridge (1871)

- Woman with a Parasol (1875)

- Grainstacks, end of day, Autumn (1891)

- Rouen Cathedral: The Facade at Sunset (1894)

- Morning on the Seine (1898)

- Charing Cross Bridge (1899)

- Grand Canal, Venice (1908)

- Water Lilies (1919)

Recommended Reading

Claude Monet’s biography and Impressionist paintings such as Monet’s garden paintings reveal a fascinating character. However, it is difficult to convey his full journey in these paragraphs. Perhaps you would like to explore more about Monet the artist in your own time. Therefore, we have included a list of book recommendations so you can do just that.

Monet. The Triumph of Impressionism (2014) by Daniel Wildenstein

Monet might be considered to have reimagined the potential of color. Monet’s paintings would indefinitely alter the way we interpret both the natural environment and its associated manifestations. The mature series of water lilies, created in his own gardens at Giverny, is considered the birth of abstract painting due to their tendency toward nearly absolute formlessness. This biography gives complete respect to this extraordinary and immensely important artist, with numerous replicas and historical pictures, as well as a thorough and incisive commentary.

- A full biography of the remarkable artist that was Claude Monet

- Offers numerous reproductions and archive photos

- Includes a detailed and insightful commentary

Claude Monet: Waterlilies and the Garden of Giverny (2018) by Julian Beecroft

A stunning new version with a silver-printed cover. Monet spent a lot of time at his cherished Giverny near the point of his death, fascinated by Japanese water gardens. The waters were only disturbed by bamboo and water lilies, which were decorated with blue sage, poppies, dahlias, and irises. His water gardens were initially designed to fulfill a desire to be close to the water as well as to present a great spectacle that could be appreciated from his home. A silver birch Weeping willow dangled over the pond’s margins, stroking the leaves of the foliage and petals below. Its iconic green wooden bridge across the pond was created, and it became the focal point of many of his paintings. “It took me a while to grasp my water lilies,” he added. “I planted them for fun,” he explained, and he got to work.

- A gorgeous new edition with the cover printed on silver

- A focus on Monet's works from Giverny as well as other works

Mornings With Monet (2021) by Barb Rosenstock

Monet enjoyed painting what he observed around him, especially the Seine River. He was first rejected because of his use of brilliant colors and tangled brushstrokes—he was chastised for his perceptions. However, art dealers and enthusiasts quickly began to queue each morning to see what Monet saw. Monet, on the other hand, merely waited for the light. The shifting light…every morning, he had a dozen panels ready to paint a dozen distinct scenes. His brush went to and fro’, chasing sunshine, putting forth the attempt to produce a picture that appeared to be created with no effort at all.

- A new picture book about the iconic artist Claude Monet

- A moving tribute to creativity, commitment, and new perspectives

- From the Caldecott-Award winning team of The Noisy Paint Box

Claude Monet’s paintings broke from the traditional art of the time’s straightforward representation of forms and linear views, instead of experimenting with free handling, powerful color, and startlingly unconventional groupings. The focus of Claude Monet’s artwork shifted from representing persons to communicating various qualities of lighting and atmosphere in each scenario of his impressionist paintings. In his later years, Monet the artist became more receptive to the decorative qualities of color and shape.

Read also our Claude Monet Artist web story.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Style Were Claude Monet’s Artworks?

Monet the artist and his fellow Impressionists aimed to show life in a way that had never been done before. Colors and the lighting that generated it was in the front of the visual in the Impressionist style. Human characters and epic narratives took a back seat, and the way the sun or moonlight showered objects in various sorts of light became crucial.

Why Was Monet’s Artwork Revered?

Monet’s approach was crucial to this trend, as the artist strove to depict color and light in new and inventive ways. His desire to capture this aspect of art led him to the Mediterranean and numerous locales in central Europe. As a result of such investigation, the birth and origin of a creative movement that is still highly regarded today resulted.

What Are Impressionist Paintings?

A philosophy or technique in painting, particularly among French painters about 1870, of representing the natural looks of things using dabs or strokes of primary unmixed colors to replicate true reflected light. The description (as in literature) of a scene, emotion, or character using details designed to produce a vividness or effectiveness through invoking subjective and sensory perceptions rather than replicating an objective reality Claude Monet’s Artwork Impression Sunrise (1872) is the first example of an Impressionist painting. Impressionist paintings depict lifelike themes painted in a wide, fast style, with visible brushstrokes and brilliant colors.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Claude Monet – The Impetus for Impressionism.” Art in Context. December 22, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/claude-monet/

Meyer, I. (2021, 22 December). Claude Monet – The Impetus for Impressionism. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/claude-monet/

Meyer, Isabella. “Claude Monet – The Impetus for Impressionism.” Art in Context, December 22, 2021. https://artincontext.org/claude-monet/.