Pointillism – The Neo-Impressionist Dot Painting Technique

With the name originally being coined by art critics as a way to ridicule the technique, Pointillism developed as part of the Post-Impressionist movement in the late 1880s. This art technique involved painting tiny yet distinct dots next to one another in order to form an image. Many artists began to adopt this technique of painting and after the 1890s, once Pointillism has reached its peak, it led the way to the development of the Fauvist art movement.

Table of Contents

- 1 What Is Pointillism?

- 2 A History of Pointillism

- 3 Technique and Practice of Pointillism

- 4 Characteristics of Pointillism

- 5 Understanding the Distinction Between Pointillism and Divisionism

- 6 Understanding the Distinction Between Pointillism and Dotted Art

- 7 Famous Pointillism Artists and Their Paintings

- 8 The Legacy of Pointillism

- 9 Influence of Pointillism on Contemporary Artists Today

- 10 Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Pointillism?

The revolutionary painting technique that eventually became known as Pointillism attempted to use the science of optics when creating paintings. This was done by painting small but separate dots of unmixed colors side by side, which were placed in various patterns in order to form an image.

The effect that this had was that in placing the dots so close to one another, they would automatically blur into an image by the eyes of viewers. This technique resembles the way computer screens work today, as the pixels on the screen resemble the dots in a Pointillism painting.

Pointillism art reinvented the use of painting with small dabs of paint that were made famous by the Impressionist movement, to the point where artists attempted to produce an entire painting out of these little dots of pure color. Therefore, it is often viewed as part of the Post-Impressionist movement, as it rose in popularity between the 1880s and 1890s after the Impressionist period had ended.

One may wonder why artists went to so much trouble to develop this innovative yet uniquely complex technique. This was simply due to the fact that they wanted to remodel and transform what art stood for. In doing so, they were able to present a new definition of what it meant to be an artist at the time.

A History of Pointillism

Primarily invented by French artists Georges Seurat and Paul Signac in 1886, Pointillism developed in response to the popular movement of Impressionism that dominated. Pointillism contrasted heavily against other art techniques that were created during the Impressionist movement, as it required a much more scientific approach to be taken by artists. Impressionism was still largely based on the subjective opinions of individual artists at the time, which many artists who sought a new art technique did not agree with.

Along with Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, many other notable French, Belgian, and Italian artists existed as leading members of the Pointillist group. Some of these artists were their fellow Frenchmen Maximilien Luce and Henri-Edmond Cross. Other artists briefly experimented with the Pointillist style at one point in their careers, such as Vincent van Gogh and Pablo Picasso.

The term “Pointillism” was initially made up by art critics as a way to mock this seemingly absurd art technique. However, as the popularity surrounding the technique grew, Pointillism was adopted as the official name and abandoned its earlier derogatory implication.

Before it was known as Pointillism, this style of painting was referred to as “Divisionism”, which has since gone on to develop into a similar yet distinct technique of painting

Pointillism art, which established itself during the Neo-Impressionist period of art, attempted to mimic the way that light works, as small individual dots were packed tightly next to each other to allow optical mixing to take place. When viewed from afar, the result of this technique meant that the viewer’s mind and eye would be able to blur the dots together in order to create a detailed image. This optical mixing also displayed images that had a more complete and vivid range of hues than what the singular dots were able to provide alone.

While Impressionist artists like Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet often made use of tiny dabs and strokes of paint as part of their technique, the Pointillist style extended this idea further. As an art technique, Pointillism was relatively easy to understand as it solely comprised of applying small dots of color onto a canvas. Additionally, pioneers Seurat and Signac made the style look very simple through the exquisite paintings that they produced when in fact the technique was quite complex to get right.

Due to Pointillism attempting to imitate how light and color were perceived, it existed as a very scientific and technical style. This meant that artists practicing this technique had to be well-informed about where to place their dots in relation to their other spots of color in order for their images to correctly form at a later stage.

As more artists began adopting this famous dot painting technique, which was also referred to as “dotted art” in a more colloquial context, the Pointillist technique became one of the most forward-thinking art styles of that era. As it presented an entirely new understanding of the subject of color studies, Pointillism had a massive influence on various art movements that developed. These spanned from the end of the 19th century throughout the avant-garde stages of the 20thcentury.

While the Pointillist approach was primarily seen to belong exclusively to the Post-Impressionist movement, it also had an impact on the subsequent development of both Cubism and Pop Art. When considering the contemporary art trends today, many artists still make use of this remarkable technique in their art.

Elements of Pointillism are also seen in the pixels from digital screens and in computer art today. However, while the logic may appear to be similar, the style and context of pixel art and Pointillism are vastly different.

Technique and Practice of Pointillism

Inspired by the Impressionist paintings of the day, Seurat and Signac attempted to recreate paintings that depicted light in its changing qualities through a new technique, in order to produce paintings with overwhelming brightness. Seurat began to place small dabs and points of pure color onto a canvas in certain patterns that would transform into beautiful images when viewed together, and thus Pointillism art was born.

The technique of Pointillism was difficult for artists to get the hang of at first, as it took advantage of the way in which our eyes function with our brains. When looking at a Pointillist painting, our eyes automatically blend the numerous different colored dots to form a solid image. Due to the scientific influence behind this technique, very few artists exist who still paint this way today.

As it was loosely related to Divisionism, many wondered: what is Pointillism? Essentially, while Divisionism was interested in color theory, Pointillism placed its focus on the specific style of brushwork that was used when applying paint. Thus, Pointillism existed as the more technical variation of this specific style. Pointillism existed as a stark contrast to the traditional methods of mixing pigments on a palette, as the technique relied on the ability of the eyes and minds of viewers to mix the color spots into various tones.

This famous dot painting technique is similar to the four-color CMYK printing process that is used by color printers today, where cyan (C), magenta (M), yellow (Y), and black (K) are combined to produce different colors. Whilst this process can be compared to Pointillism due to some loose similarities, Pointillism placed greater focus on a variety of features that made up the technique. These features have been explained below.

Science of the Eye

Pointillism was one of the most scientific approaches that developed in relation to the production of art. An important influence on the theory behind Pointillism was French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul, who wrote a book while researching ways to improve the strength of colors for a Parisian tapestry company. Chevreul concluded that the visual impact of the tapestries relied on optics and the juxtaposition of complementary colors, with Pointillism drawing heaving on these results in the paintings that were produced.

Points of Undiluted and Unmixed Color

When using the Pointillist technique, artists made use of dots of pure and unblended colors when creating their paintings. These dots were then carefully placed in areas where the artist knew they would be correctly blended by the viewer’s eye and have a more striking effect. Due to this, artists never mixed colors as once they were blended, they somehow lost their luminosity. Additionally, the smaller these dots were, the sharper the lines were and the clearer the painting became.

Precise Technique

This Neo-Impressionist technique was an incredibly meticulous one, as it focused on the idea of optical illusion. Pointillism artists rejected fluid and spontaneous strokes in favor of a more accurate and methodical way of painting. Every Pointillism painting was carefully planned out before artists began applying paint so that they knew more or less what the outcome of their artwork would look like. Due to the technicality of this technique, most Pointillism art was done in oil paint, as it was preferred for its thickness and tendency to not run.

Characteristics of Pointillism

Pointillism was an Impressionist-inspired technique that looked to reinvent the way landscapes, portraits, and seascapes were painted within the Neo-Impressionist movement. Its name was influenced by art critic Félix Fénéon, who first used the expression “painting by dots” when attempting to describe this curious style of painting.

While Seurat preferred the name “Divisionism” or “Chromoluminarism” for the technique he invented, “Pointillism” was eventually derived from Fénéon’s expression and stuck.

Rather than mixing color on a palette before using them, Pointillism was characterized by its application of pure colors directly placed on a canvas. This was because raw pigments were able to hold their genuine brightness when left unblended, which made the technique of Pointillism so groundbreaking. Additionally, round or sometimes square brushes were used when painting, which allowed the blending of the colors to happen on the canvas through the viewer’s eye.

Pointillism was also characterized by a saturation of the tones used, as colors were typically vivid and bright. When creating these intense colors, Pointillism artists used different varieties of the same shade without blending the pigments. In doing so, they helped canvases to look softer and less visually hostile, in addition to creating these vibrant hues. This excessive use of color in Pointillism art was said to have paved the way for the development of the Fauvist and Surrealist movements, as they both made use of striking colors.

Lastly, one of the main characteristics to define Pointillism was that the dots were only able to be differentiated from one another when viewed from a specific distance. Generally, the spotted touches of the paintbrush required viewers to automatically take a few steps back in order to see the emergence of the painting as a whole.

Thus, Pointillism paintings were characterized by the distance they required from viewers when looking at the completed artwork, as the further away the viewer was, the more “whole” the painting appeared.

Understanding the Distinction Between Pointillism and Divisionism

At certain times throughout art history, Pointillism has been incorrectly associated with Divisionism. This was because the technique of Divisionism, sometimes referred to as Chromoluminarism, emerged at the same time as Pointillism and was also thought to be part of the Post-Impressionism movement. Divisionists made use of a similar approach when forming images through the patterns created, but the final result of their practice differed vastly from Pointillism.

Divisionism surfaced due to the scientific theories and rules of color that had been established and was influenced by the theory of contrasting colors, which was developed by French art critic Charles Blanc. While Divisionism was engaged with colors and how they could be divided, Pointillism focused on the possibilities of creating patterns out of dots that formed into coherent images when viewed from afar. This difference was seen in Pointillism art, as no consideration was given to the separation of colors once the piece had formed.

Possibly the biggest difference between these two styles was seen in the final product, as Divisionists made use of bigger cube-like brushstrokes, while Pointillism artists characterized their composition with small, multicolored dots.

Ultimately, the confusion between these two art techniques was thought to be based on the fact that the same group of artists who developed Pointillism helped facilitate the emergence of Divisionism. Seurat, Signac, and even van Gogh were known to practice with both techniques.

Understanding the Distinction Between Pointillism and Dotted Art

While Pointillism has been referred to as “famous dot painting” in the past, the technique is essentially the same thing as Dotted Art. The only difference that exists between these two terms is that “Pointillism” is used by art historians and collectors to refer to artworks that have used this technique, while “Dotted Art” is used in a more colloquial setting amongst the general public.

A well-known example of Dotted Art is Aboriginal art, which made use of dots and stipples within the famous rock paintings. However, Dotted Art is used to refer to the work of amateur artists today, as the term places less pressure and expectation on the works that are produced as opposed to labeling them as Pointillism art.

Thus, apart from these contextualizing differences, nothing else stands out that differentiates Pointillism from Dotted Art.

Famous Pointillism Artists and Their Paintings

Many of the artworks that were created using the Pointillist technique exist as some of the most significant paintings to date. In this next section, we will be taking a look at and exploring some of the most well-known Pointillism artists and their infamous Pointillism art.

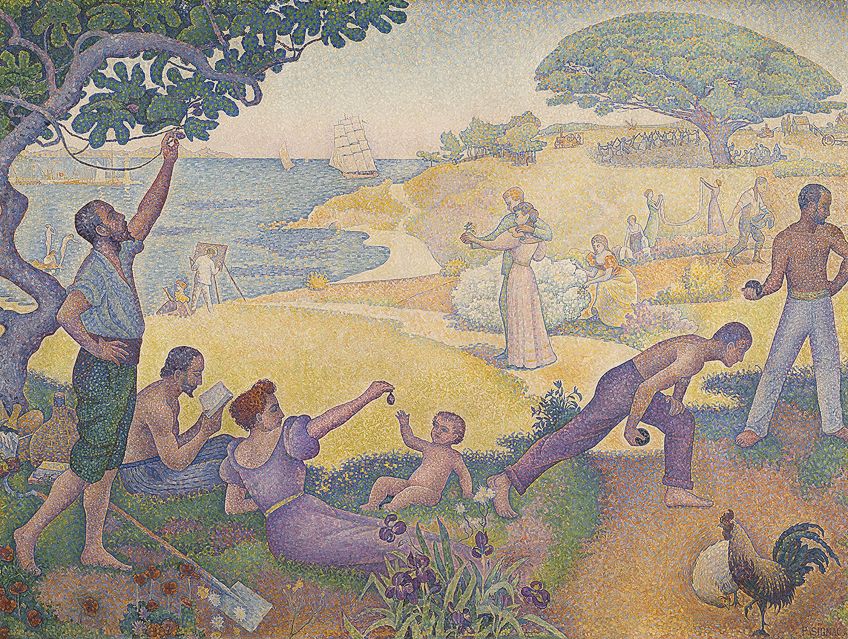

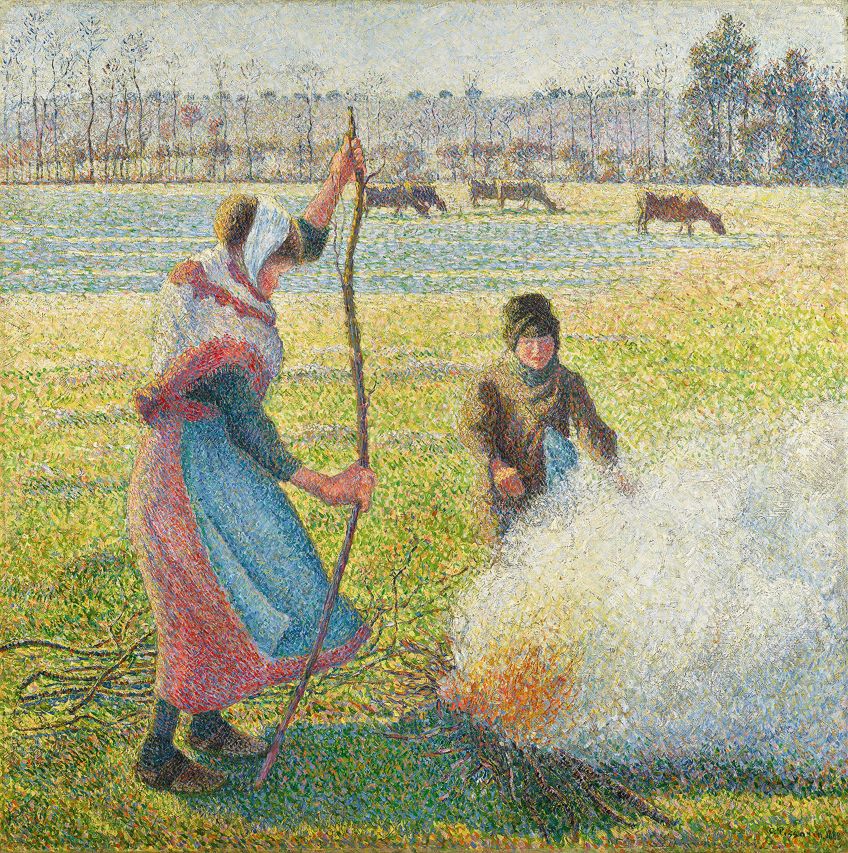

Camille Pissarro (1830 – 1903)

Practicing within both the Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist movement, Danish-French artist Camille Pissarro perfected his technique of portraying the ordinary life within his paintings. Pissarro sought to explore new themes and methods that would allow him to break out of the contemporary painting style of his time, choosing to return to depictions of ordinary individuals in very realistic settings.

It was at this point in his artistic style when Pissarro met Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, who had already begun to use the Pointillist technique. Pissarro readily embraced and implemented Pointillism in his works and was one of the artists whose works greatly stood out within the Pointillist group. A well-known Pointillism painting of his is Gelée Blanche, Jeune Paysanne Faisant du Feu, which he painted between 1887 and 1888.

Existing on quite a grand scale, this painting demonstrates how Pissarro was able to manipulate the complex subject of light. His brilliant depiction of the intricacies between light and atmosphere is seen by his portrayal of both heat and cold, as the low sun is shown to be casting shadows on the meadows and the remaining night frost. Additionally, some mist can be seen rising in the background, which is contrasted against the weak yet shimmering light that is depicted.

Within this painting, Pissarro was able to create an extraordinary and uniquely subtle illustration of smoke, fire, and cold air, that was not able to be matched in other Pointillist art produced. In addition to the brilliance Pissarro displayed when considering the effects of light, his empathetic approach to the human condition within his artworks set his paintings apart from others.

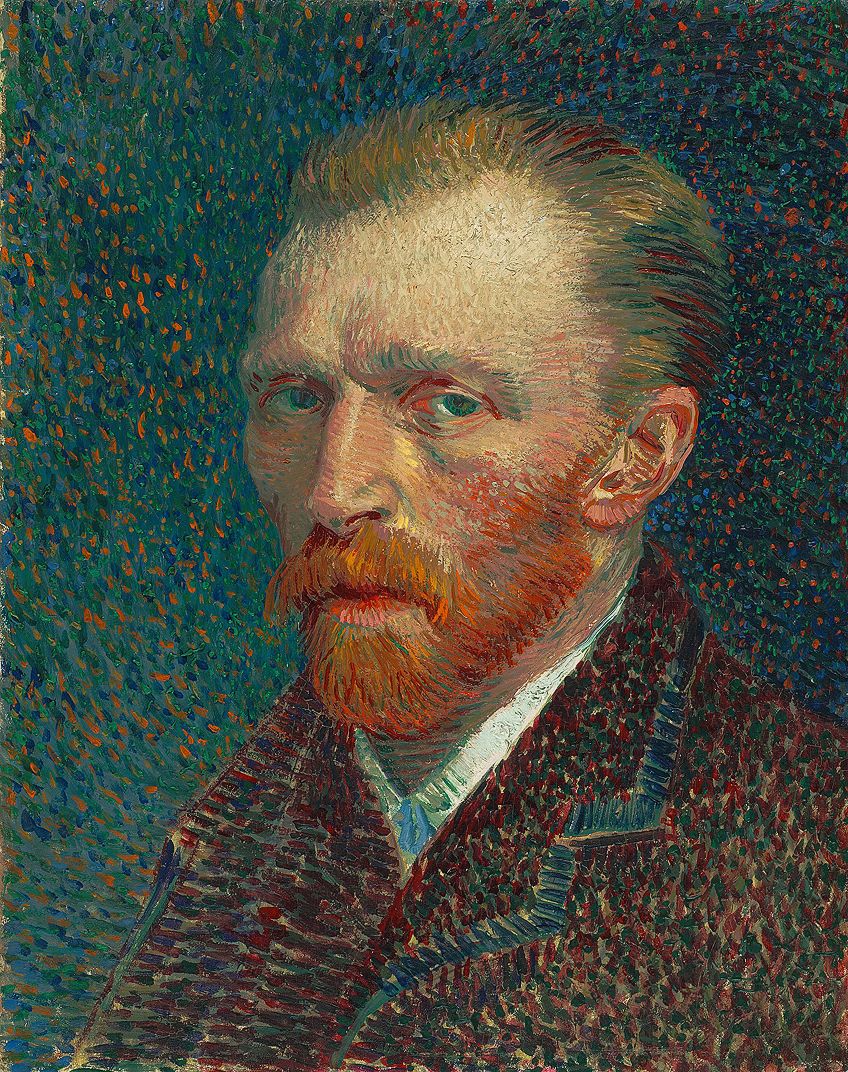

Vincent van Gogh (1853 – 1890)

A Dutch painter who was known to briefly experiment with Pointillism was Vincent van Gogh. After visiting Georges Seurat’s studio, van Gogh exclaimed that he had come into contact with a “revelation of color”, which led to him beginning to paint using the Pointillist technique. However, it was generally agreed by art historians that van Gogh was too much of an unsettled spirit to continue within a style as technical as Pointillism, as demonstrated by him moving on from the technique after a short period of time.

A well-known painting of van Gogh’s that clearly demonstrates the use of Pointillism is his 1887 Self Portrait. Within this painting, van Gogh responded to Seurat’s iconic painting, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884), and made use of thick brushwork which would go on to become a trademark of his style. However, the difference in van Gogh’s painting was that he attached passionate emotional language to his color palette chosen, while Seurat and other’s artists based their technique on the cool detachment related to science.

The surface of Self Portrait dazzles with specks of color including greens, blues, oranges, and reds. The contrast between the cool and warm tones creates a sparkling effect, as it appears that the background behind van Gogh is full of movement. While viewers cannot help but get caught up in the rhythm created by the abrupt and disconnected dabs of paint, van Gogh’s deep green eyes seem to convey a deep intensity that acts as another focal point in the work.

Van Gogh demonstrated a great skill for expressing the fluidity of light, which was taught to him by fellow artist Camille Pissarro.

Van Gogh became a temporary tenant in Pissarro’s home and during this time spent together, Pissarro taught him the different ways of finding and expressing light and color, with this skill being identified in his Self Portrait.

Charles Angrand (1854 – 1926)

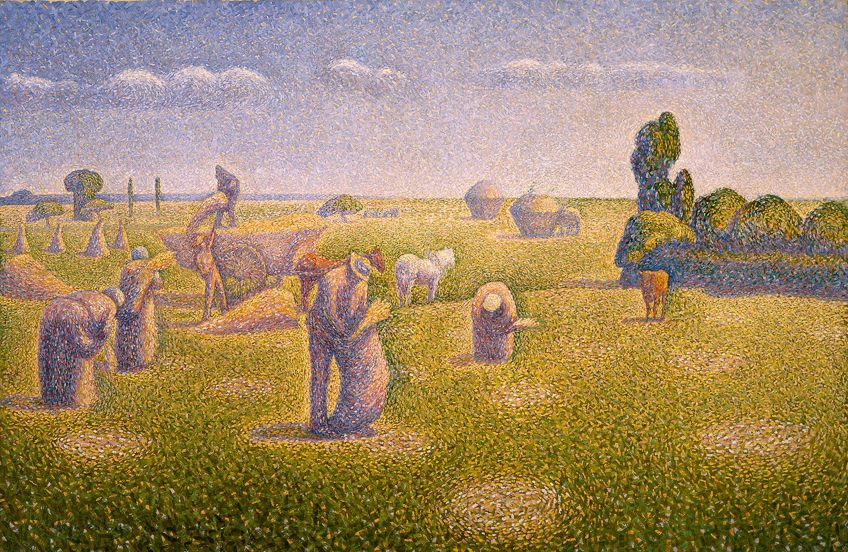

Another French artist who gained widespread acknowledgment for his paintings was Charles Angrand. Influenced by members of the Pointillist group, such as Camille Pissarro, Georges Seurat, and Paul Signac, Angrand began to implement Pointillist techniques within his own paintings, despite his implementations different from the work of other Pointillism artists.

One of Angrand’s notable Pointillism paintings is The Harvesters, painted in 1892. Within most of Angrand’s artworks, you can see that his choice of colors is more subdued than the bright and contrasting colors that were typically used in the works of Seurat and Signac. Angrand was said to consciously avoid the violent coloration observed in many other Pointillism paintings, as he felt that his muted theme allowed him to better capture and execute depictions of light in his artworks.

However, within The Harvesters, Angrand copied the style and color palette of Seurat and Signac, with this painting existing as one of his more colorful artworks. This is demonstrated by the warm tones used to depict the workers in the field, in addition to the seemingly heated glow of light that appears to be washing over them.

The contrast created between the warm tones of the figures and the cool tones found within the background demonstrates how perceptive Angrand was when it came to portraying the transient element of light.

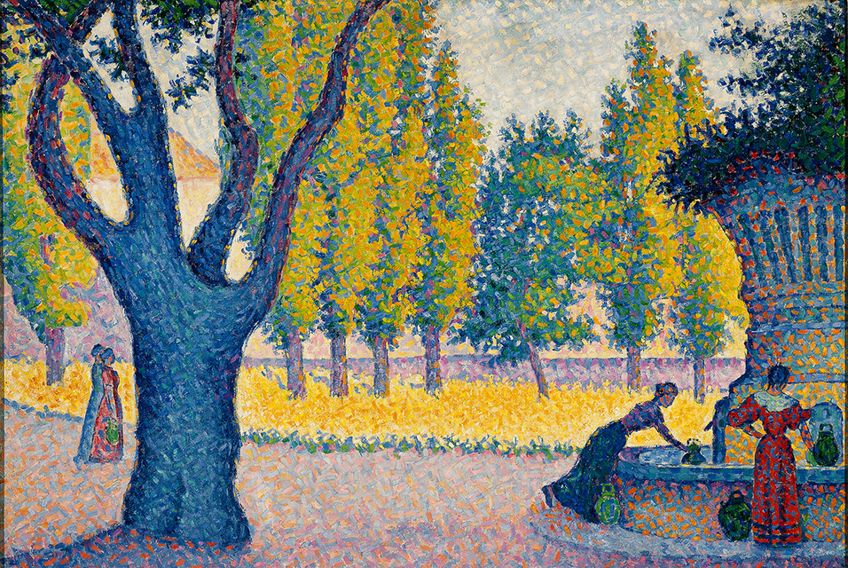

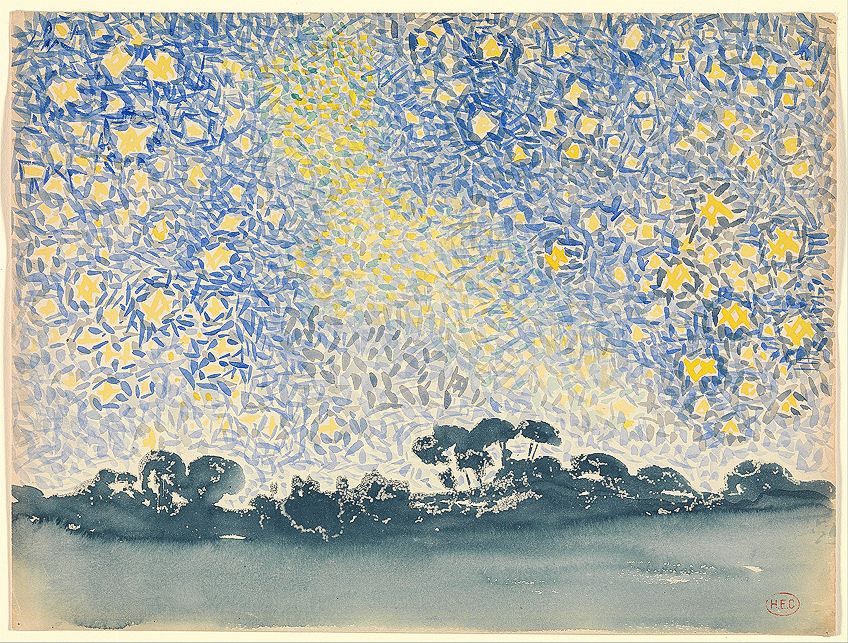

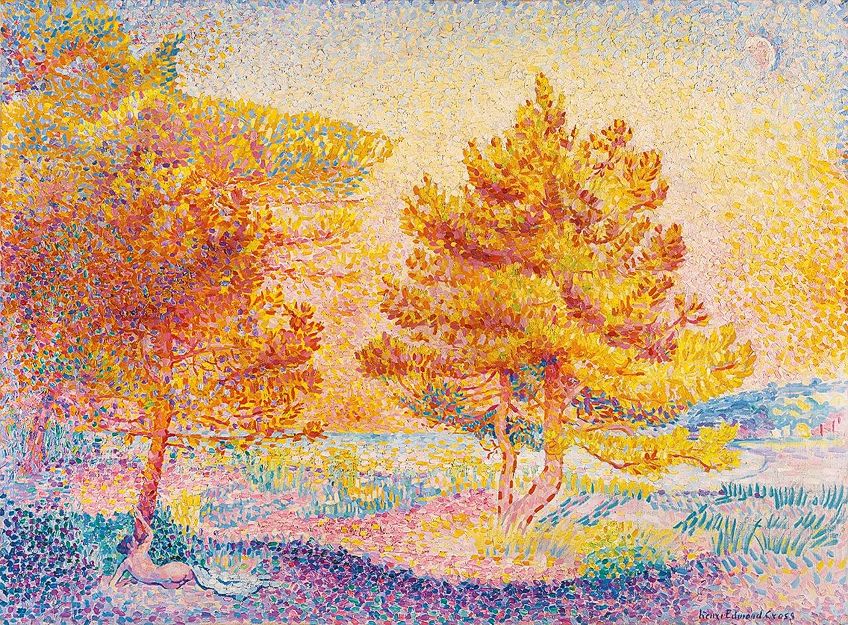

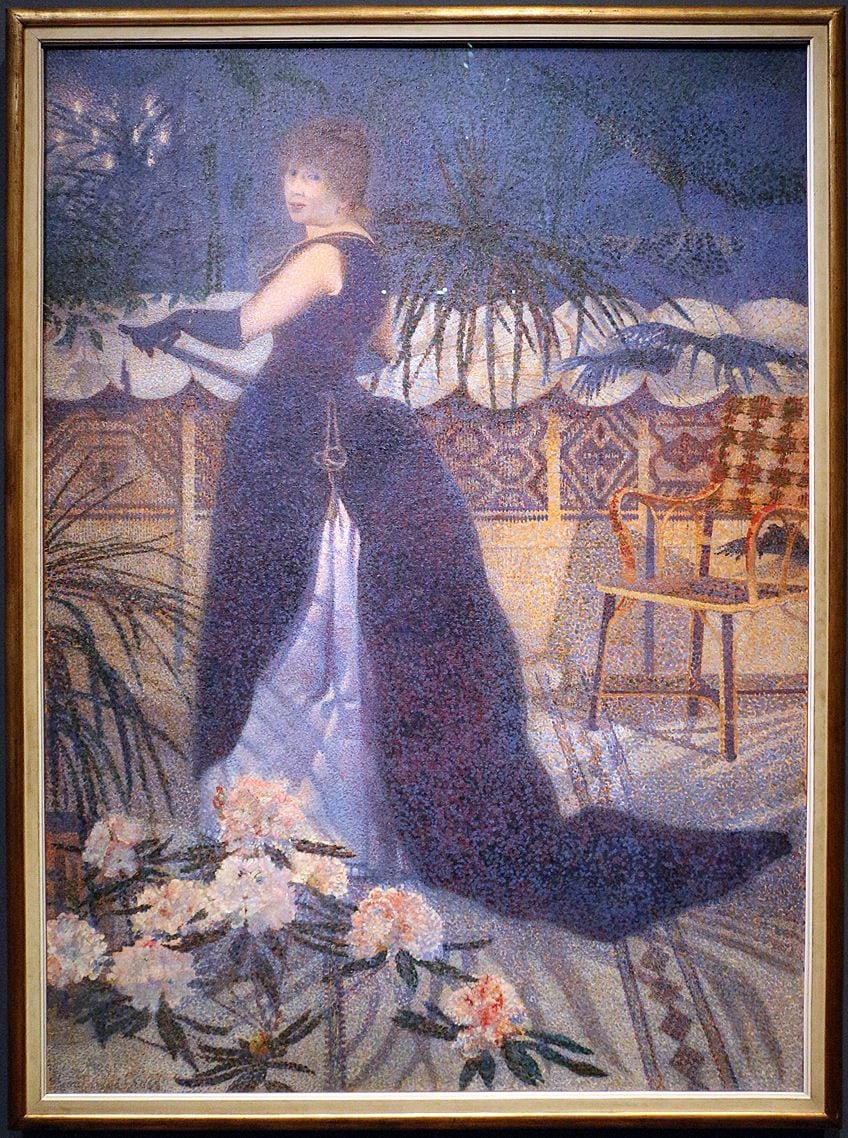

Henri-Edmond Cross (1856 – 1910)

French painter Henri-Edmond Cross was a famed artist within the Neo-Impressionist movement and was among the most significant artists who made use of the Pointillist technique. While experimenting with Pointillism, Cross exerted an instrumental influence on the art world, which helped pave the way for the development of Fauvism. In 1884, Cross co-founded the “Société des Artistes Indépendants” which led to his meeting of creatives who shared the same values, including Pointillism artists Georges Seurat and Charles Angrand.

Despite forming a close relationship with these artists, Cross only began to paint using the Pointillist technique in 1891. His first Pointillist painting, created in that same year, was a portrait of his future wife and was titled Madame Hector France. Within this large, full-length portrait of Irma Clare, who was married to the writer Hector France at the time, a careful balance between light and shade is depicted.

The light, which is suggestive of a summer night, is represented by the twinkling lamps in the background, as well as the white rhododendron that is seen in the foreground. These areas of illumination are further contrasted with the dark colors that are used to depict Madame France’s dress, including the slight shadow that falls across her face. Within this painting, Cross was also able to create the illusion of depth and space, by portraying the chair at an angle, and the inclusion of the geometric shapes that cover the floor.

Despite employing the techniques of Pointillism, it has been said that Cross’ painting was more Divisionist in style. This was because his portrait seemed to have a grainy yet atmospheric glow to it, which possibly demonstrates a greater focus on the division of colors as opposed to the patterns of the dots.

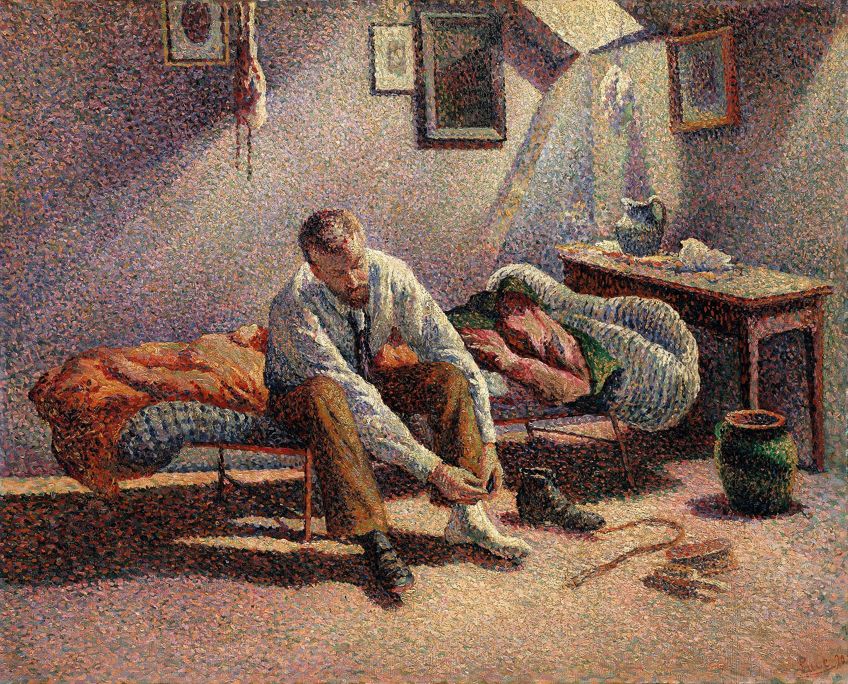

Maximilien Luce (1858 – 1941)

Another prominent French artist who was significant within the Pointillism era was Maximilien Luce, who eventually returned to Impressionism once Pointillism began to decline. Within most of his Pointillist artworks, Luce depicted scenes of ordinary people at work. One of his most notable pieces, which shows a man getting ready for work in the morning, was Morning, Interior, painted in 1890. The man in this painting was said to be Luce’s close friend and fellow Neo-Impressionist artist, Gustave Perrot.

Within this painting, a young man is shown to be sitting on a flimsy bed while putting his left boot on. The room is scantily furnished, but what grabs our attention is the depiction of the early morning sunlight that is streaming into the room through the windows. In an attempt to capture this light, Luce rendered the room in points of yellow, orange, and red, which creates a vibrant portrayal of the warmth brought forth by the light. Spots of light blue and violet can also be seen, which complement the warmer tones and further emphasize the light present.

The contrasting colors used by Luce help to modulate the differing fall of light throughout the room, as demonstrated by the colors used to show the vase, bedclothes, and vase. Through this gentle depiction of light, an incredibly intimate scene is shown of an individual presumed to be the artist Perrot going about his morning activities of getting dressed in his simple living quarters. The stippled technique that Luce made use of within this painting was uniquely Pointillist, showing his influence over the style.

Georges Seurat (1859 – 1891)

The first pioneer of Pointillism and the most important artists within this technique was French painter Georges Seurat, whose short career made a great impact on the artistic community. Typically known as Seurat Pointillism, this technique helped Seurat found the Neo-Impressionist movement within which Pointillism fell and practiced. Seurat was incredibly mathematical in his approach to Pointillism painting, with his precision and logical abstractions being viewed in the majority of the artworks he created.

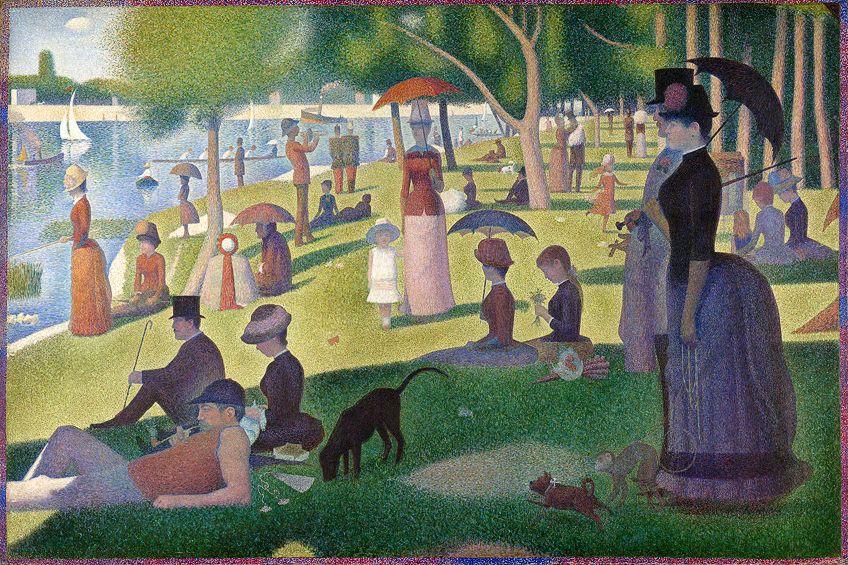

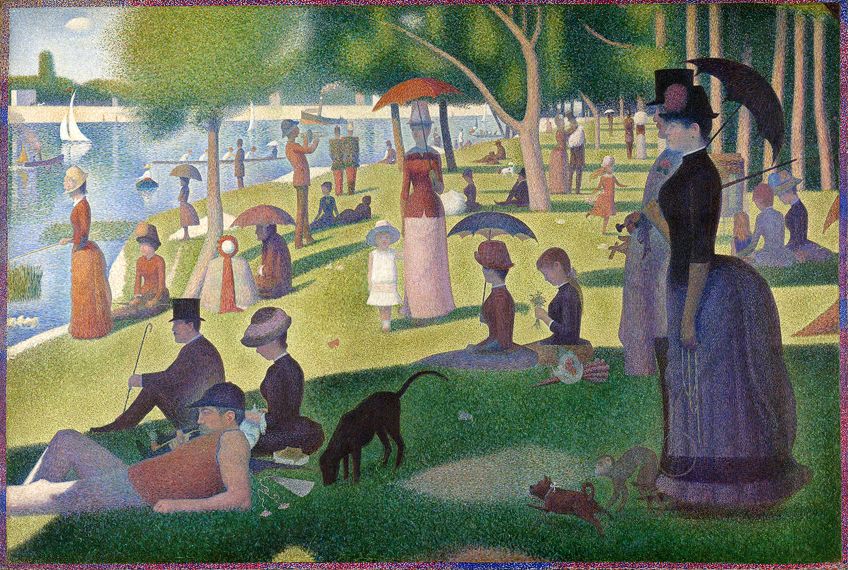

Possibly the most well-known masterpiece of Pointillism, in addition to being one of the most significant paintings created within art history, is Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, painted between 1884 and 1886. This painting portrays members of different social classes relaxing on an island in the Seine River known as La Grande Jatte and taking part in various park activities.

Seurat worked in a highly systematic way and completed this entire painting through the use of tiny dots that contrasted in color, which allowed the viewer’s eyes to blend the colors optically. Due to the sheer size of the artwork and the technicality of this style, it took Seurat two years to fully complete this painting, as he spent the majority of that time in the park sketching about 60 studies in preparation.

A masterful manipulation with light and shadow can be seen, as the shimmering river contrasts heavily against the shade in the bottom left corner, as well as the shadows created by all of the figures who are standing upright. Additionally, the inclusion of umbrellas adds to this idea of shade, as the figures holding the umbrellas are bathed in both shade and light.

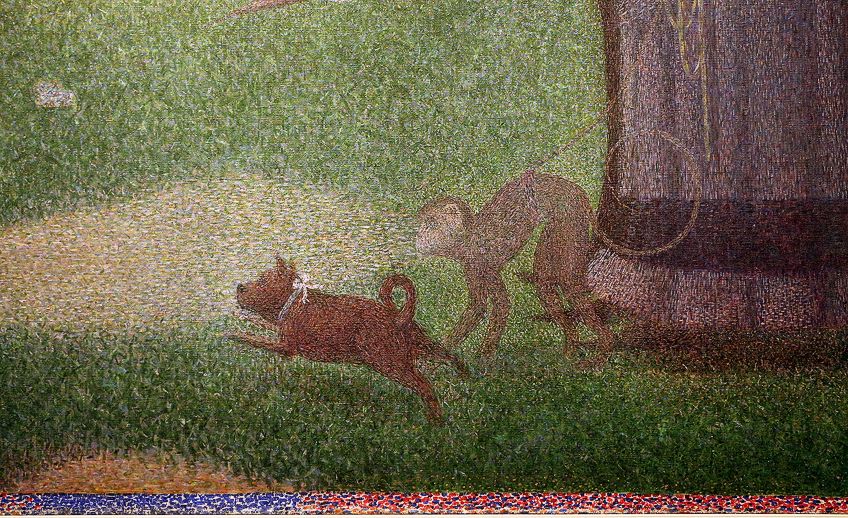

Despite Seurat’s artwork taking a more scientific and intuitive approach to art creation, not all is as it seems. Upon closer inspection, certain anomalies jump out.

For example, the lady depicted in darker tones in the bottom left corner appears to be holding a monkey on a leash, which is running next to a dog. Another deviation from the style so carefully created by Seurat within this work is seen in the little girl placed in the middle of the composition, as she is the only figure to be portrayed without a shadow.

In 1889, Seurat made one final change to A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. He lengthened the canvas so that he could add a painted border made up of orange, red, and blue dots. This was done to provide a visual passageway between the inner of the painting and its white frame. Unfortunately, Seurat’s life ended tragically at the age of 31 due to diphtheria. However, the legacy of Seurat Pointillism lived on through other notable artists who experimented with his technique.

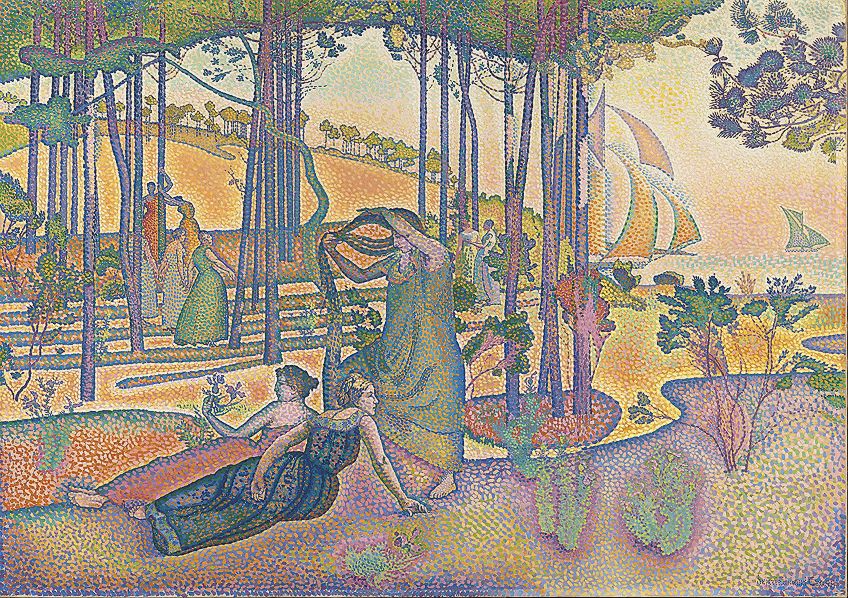

Théo van Rysselberghe (1862 – 1926)

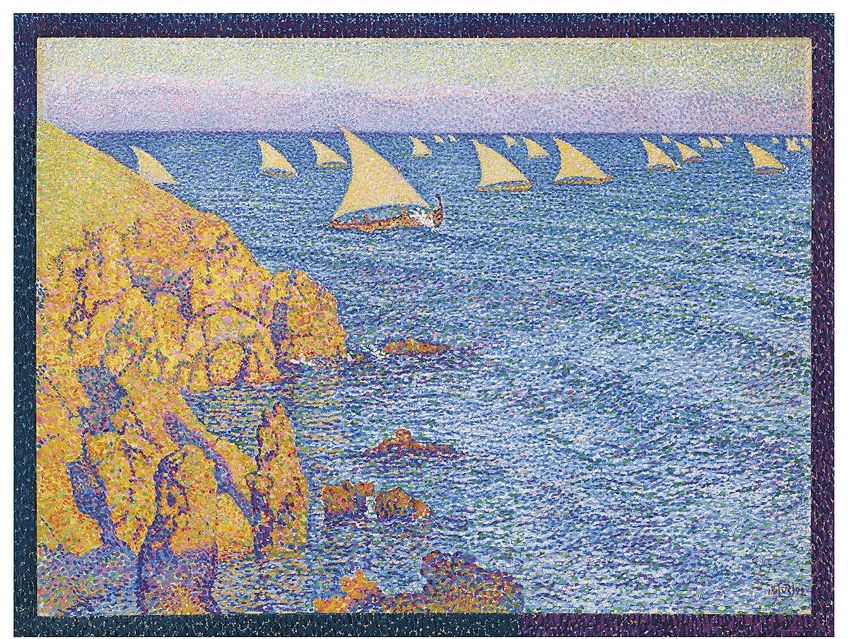

Belgian artist Théo van Rysselberghe was another prominent artist who made use of Pointillism and played a crucial role in the European art scene at the beginning of the 20th century. Van Rysselberghe typically experimented with portraiture during his Pointillism period, as he often painted portraits of his wife and daughter. However, some of his more iconic Pointillist pieces depicted landscapes and seascapes.

One of van Rysselberghe’s most iconic Pointillist artworks, as well as one of the most beautiful Pointillist paintings to exist, is his 1892 painting Fishing Boats in the Mediterranian. This painting depicts the turquoise blue water of the Mediterranean sea reflecting the sun’s rays as the waves roll. A large fleet of fishing boats sails past an outcrop of orange-glowing rocks, basking in the golden glow of the Mediterranean light.

This painting includes some of the purest forms of divisionist applications, which can be seen in the regulation of shapes within the painting. Perhaps inspired by Impressionist Naturalism, this pointillist painting offers an abstract representation of an open seascape, complete with boats, ocean water, and sunlight. Within this painting, you can see the depiction of the natural world through ordered geometric shapes of different colors.

The complementary sets of colors of both orange and blue and yellow and purple allow for the amplification of the overall abstract composition of the painting. At the same time, however, the vantage point from which the viewer is placed hints at a precariousness of staining over a cliff’s edge, relating to the physicality of our own reality. This painting also provides a great sense of temporality in the way the unending nature of the ocean water contrasts to the fragility of the passing ships, completely helpless to the effects of the ocean, similar to how humankind is subject to the trials and tribulations of life.

Towards the end of the 1890s, van Rysselberghe abandoned the use of small dots and went on to use broader brush strokes, which concluded his Pointillism period.

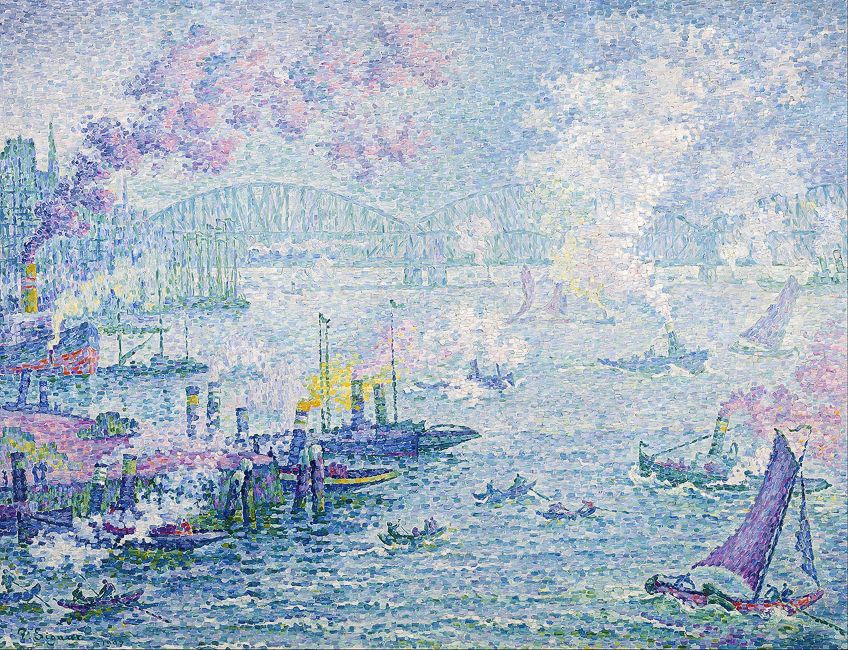

Paul Signac (1863 – 1935)

The other founder of Pointillism, as well as the second most important artist within this style, was French painter Paul Signac. Along with Georges Seurat, Signac studied and developed the technique of Pointillism alongside him, as he was a student of Seurat’s at the time. After Seurat’s untimely death, Signac continued to work within Pointillism throughout the entirety of his career and left an enormous legacy of artworks that made use of the technique.

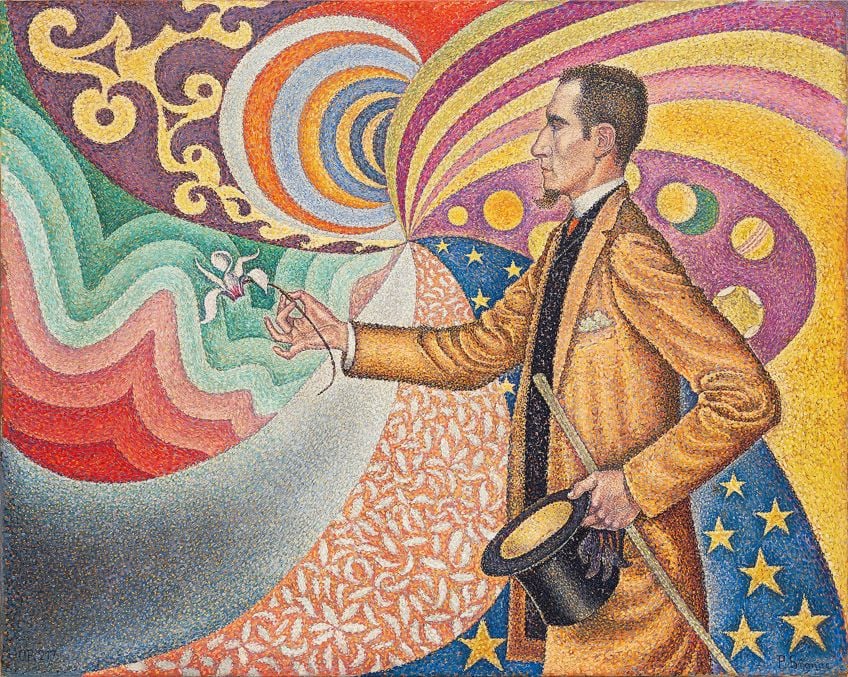

A very well-known work of Signac’s, which he painted in 1890, was titled Opus 217. Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones, and Tints, Portrait of M. Félix Fénéon. Within this painting, Signac honored his friend, influential art critic, collector, curator, and dealer Félix Fénéon, in a portrait that remains Signac’s most memorable and outstanding artwork.

This portrait illustrates Signac’s preference for using vibrant and striking tones, as the combination of colors seems overwhelming at first. The color wheel depicted in the background demonstrates Signac’s impressive use of Pointillism, as viewers have to first optically blend the colors before they are able to make sense of the shapes that form.

While both Fénéon and the white flower he holds remain motionless against the symphony of colors, the title suggests motion and music through the word “Opus.” Additionally, movement is implied through the Pointillist technique within this artwork, as the dots of vibrant color seem to vibrate against one another. Fénéon’s profile adds to the movement in this painting, as his nose, elbow, and cane decline in a zigzag type of pattern that is reminiscent of motion.

Within this artwork, Signac artfully demonstrated his manipulation of Pointillism through the vivid dots and angles he made use of. Both elements added to the vibrancy that is felt when looking at this painting, as it seems to come alive with excited and animated movement when closely studied.

The Legacy of Pointillism

By the 1890s, Pointillism art had reached its peak, as many artists of the time had adopted the technique in the artworks that were produced. Pointillism had a great influence on the Post-Impressionist movement, which had spilled into the beginning of the 20th century. After this, the style slowly faded out, as most artists started to experiment with other forms of artistic creation.

Despite some artists solely practicing within this technique, while others only briefly touched on it, there is no denying the great influence that Pointillism had on art.

While Pointillism is generally considered to have had the most influence in the technical area of art, its experimentation with color theory and understanding of optical realism opened many doors for future art movements. An important movement that developed in the wake of Pointillism was Fauvism, which was inspired by the vivid use of color used by Pointillism artists. Henri Matisse’s Luxe, Calme et Volupté (1904) is often said to be an important transitional work between the two styles.

As a painting technique, Pointillism was challenging to master and due to this, not many artists are able to paint this way today. However, despite the heyday of Pointillism art being over, many of its concepts and ideas are still being used by artists in a more contemporary context, who are creating artworks in a variety of different mediums. Some of these mediums seen in Modern Art today, that were clearly influenced by Pointillism, include fashion and tattoos.

Influence of Pointillism on Contemporary Artists Today

Within the modern era, many artists are loosely experimenting with the themes and ideas that were prominent in the Pointillism style. The primary concept of dots has been restructured to fit into a contemporary setting, with many artists making use of dots in various shapes and forms for a range of different purposes.

Some artists have even created artworks based entirely on dots, demonstrating that Pointillism art remains ever-present even in the 21st century.

Damien Hirst (Born 1965)

One of the first contemporary artists that come to mind when discussing modern art is British artist Damien Hirst. While we cannot classify Hirst as a Pointillist artist, he did experiment with the technique in a series of dotted paintings that seemed to pay homage to the original style. His 1986 painting, titled Spotted Painting, was one of Hirst’s first experimental paintings that included dots. When viewing the work, numerous multicolored dots are visible, which seem to have been haphazardly placed all over the canvas.

This assumption is justified, as the further one moves away when viewing the work – in an attempt to allow the optical illusion to make sense – no figures seem to appear from the dots. No matter the distance that is created between the painting and the viewer, the dots are clearly visible from all angles. In a way, this artwork can be classified as a form of dotted art, as that is exactly what it is. Hirst’s Spotted Painting, along with the other artworks in this series, remains true to what they are, which are essentially a collection of colorful dots.

Philip Karlberg (Born 1973)

Another modern artist that has been known to incorporate dots and Pointillism theories into his works is Swedish photographer Philip Karlberg. While being inspired by dots, Karlberg’s artistic expression and subsequent creations differ vastly from the original idea of Pointillism, but its influence can clearly be seen in his works. Undertaking an immense project in 2012, which he labeled his Pin Art Portraits series, Karlberg created portraits of iconic figures using over 1200 wooden sticks meticulously arranged on wooden boards to resemble specific celebrities.

Some of the celebrities he captured included Johnny Depp, Jackie O, Lady Gaga, and Karl Lagerfeld. In each portrait, Karlberg made each celebrity wear a designer pair of sunglasses.

Within these eye-catching pieces, Karlberg was inspired by the optical illusion in Pointillism to create these works, whereby the eyes of viewers were also required to arrange the sticks into the faces of these well-known celebrities. The shadow created by each stick, which he stuck into the board at different lengths, helped to further construct the faces of each celebrity, demonstrating Karlberg’s use of strategic lighting.

Although it was said to be complicated when it first appeared on the art scene, Pointillism’s revolutionary technique led most artists at the time to experiment with it. The paintings that emerged from this period of art have gone on to become some of the most iconic artworks of all time, as no movement as mathematically technical as Pointillism has developed since. The influence of Pointillism art was also felt far and wide, with this technique being attributed to the development of other significant art movements within art history.

Take a look at our Pointillism art webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Pointillism?

The revolutionary painting technique that eventually became known as Pointillism attempted to use the science of optics when creating paintings. This was done by painting small but separate dots of unmixed colors side by side, which were placed in various patterns in order to form an image.

What Are the Key Principles and Techniques Used in Pointillism?

Pointillism is a painting technique where small, distinct dots of color are applied in patterns to form an image. The key principle of Pointillism is the optical blending of colors, achieved when the viewer’s eye mixes the dots from a distance, creating a cohesive image. Artists often use a variety of techniques to control the density, size, and placement of the dots to achieve desired effects such as texture, shading, and depth. Through meticulous layering and careful color selection, Pointillist artists can create vibrant and dynamic compositions.

Examples of Famous Artists Known for Their Work in Pointillism?

Several notable artists are celebrated for their contributions to the Pointillism movement. Georges Seurat and Paul Signac are considered the pioneers of Pointillism, with Seurat’s iconic painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte being one of the most recognizable examples of the technique. Their innovative use of Pointillism in the late 19th century sparked a new artistic movement that influenced subsequent generations of artists. Other notable practitioners of Pointillism include Camille Pissarro, Maximilien Luce, and Henri-Edmond Cross, each contributing unique styles and interpretations to the movement.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Pointillism – The Neo-Impressionist Dot Painting Technique.” Art in Context. May 14, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/pointillism/

Meyer, I. (2021, 14 May). Pointillism – The Neo-Impressionist Dot Painting Technique. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/pointillism/

Meyer, Isabella. “Pointillism – The Neo-Impressionist Dot Painting Technique.” Art in Context, May 14, 2021. https://artincontext.org/pointillism/.