Art for Art’s Sake – The Meaning of Art for its Own Sake

What is the meaning of art for art’s sake? Creating art for the sake of art refers to making “true” art that is not based on any practical function or tied to any specific social values. This concept has permeated several movements and styles, leaving a significant mark on the world of art through the years. Below, we explore all there is to know about the concept of art for the sake of art!

Table of Contents

- 1 The Meaning of Art for Art’s Sake

- 2 The Origins of the Concept of Art for the Sake of Art

- 3 Critics of Art for Art’s Sake

- 4 Art Movements Associated with Art for Art’s Sake

- 5 Art for Art’s Sake’s Effect on Art History

- 6 The Later Developments of Art for Art’s Sake

- 7 The Influence of Art for Art’s Sake in the Modern Era

- 8 Frequently Asked Questions

The Meaning of Art for Art’s Sake

Art for the sake of art is the belief held by certain artists that art has intrinsic worth irrespective of any political, social, or ethical relevance. They believe that art should be assessed only on its own merits: whether it is aesthetically pleasing or not, and capable of creating a sense of awe in the observer through its formal features.

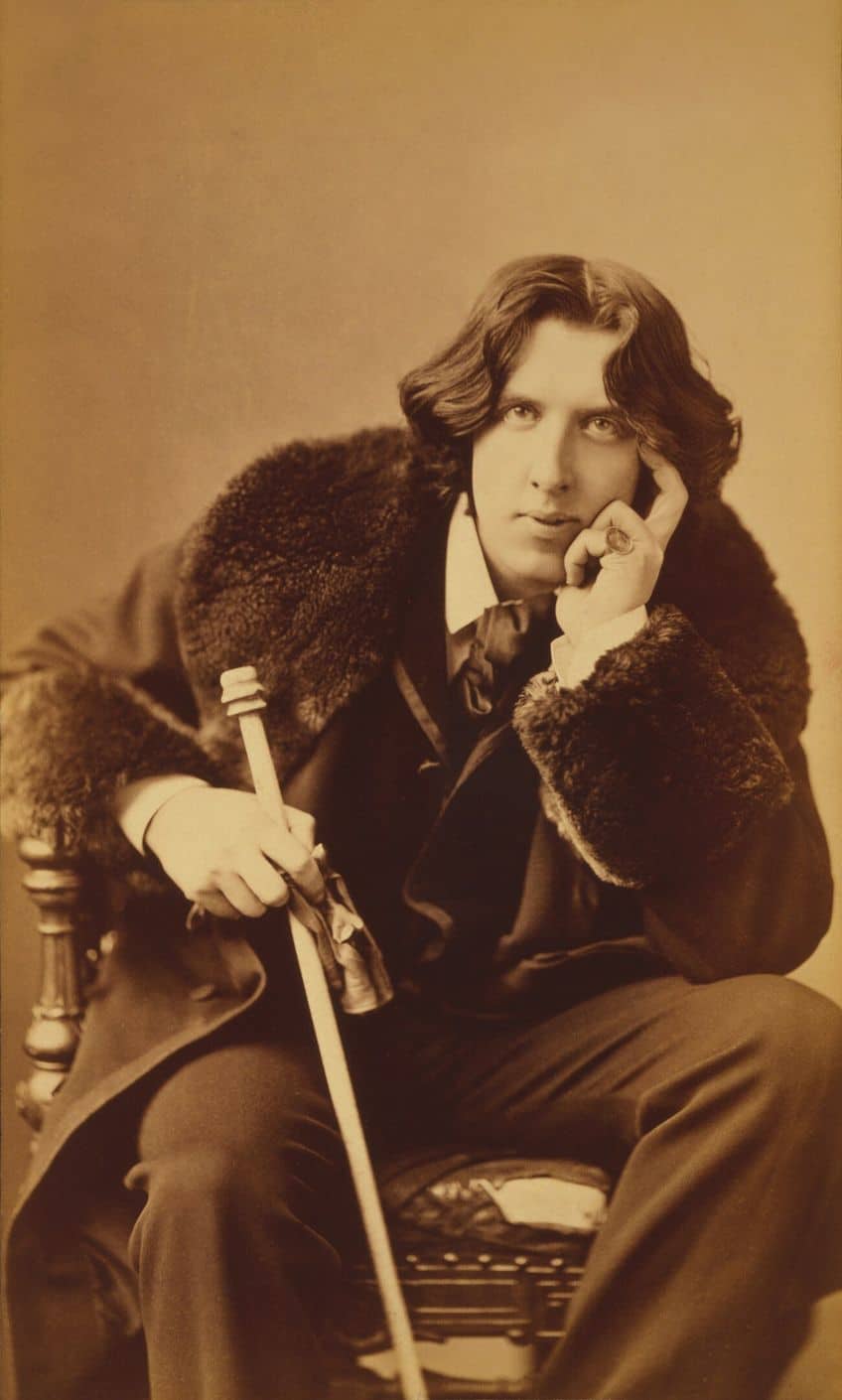

This idea became a rallying cry across 19th-century France and Britain, partially in response to the suffocating moralism that characterized much academic art and broader culture, with writer Oscar Wilde arguably its most prominent defender. Although the expression has seldom been employed since the early 20th century, its impact and legacy can be observed in a number of 20th-century ideas about art’s autonomy, particularly in different kinds of formalism.

The Origins of the Concept of Art for the Sake of Art

This concept can be traced back to the European Romantic movement, notably in Germany and England, when artists and intellectuals started advocating for the idea that art should be appreciated for its intrinsic characteristics rather than for any external or utilitarian role. Prior to this change, art was often considered a way of communicating certain political, religious, or moral ideas, or as a kind of social commentary. Artists were required to follow particular rules and regulations, and their artwork was judged based on its ability to represent certain concepts or ideals.

As the Romantic movement gained traction, however, there was a rising desire for artistic freedom that would break away from these restraints and enable art to exist and be enjoyed solely for its visual and emotional impact.

Important Figures

One of the significant individuals involved with the formation of the notion of art for the sake of art was Immanuel Kant, the German philosopher. Kant asserted in his important book The Critique of Judgment (1790) that the ultimate goal of art was to offer an enjoyable experience independent of any utilitarian or moral concerns. He stressed the autonomous nature of aesthetic judgments, implying that the significance and value of art lay in its ability to elicit pleasure in the observer.

Another significant individual who believed in art for art’s sake was Samuel Taylor Coleridge, a critic, and poet from England. He asserted that the essential goal of art was to provoke and communicate emotions, arguing that art should be independent of any external aim or message. Coleridge’s opinions, like those of other Romantic writers like John Keats and William Wordsworth, contributed to the emerging movement that valued art for its own inherent merits. In the 19th century, the idea of art for art’s sake continued to expand and gain popularity, notably through the works of French figures such as Charles Baudelaire, Walter Pater, and Théophile Gautier.

In his prologue to the book of poems Émaux et Camées (1852), Gautier famously wrote, “Art for art’s sake”, demonstrating how popular the idea had grown.

Being artistically inclined, according to Pater, is “to shine constantly with a hard, gem-like fire, and to preserve this ecstasy, is an accomplishment in life”. As one historian put it, “Such a heightened, if excessive, ideal of art sought a new kind of critique that would meet, and even exceed, the power of the impressions that a work of art stirred in the responsive audience, and the aesthetic critic answered with passionate poems of his own. Proper Victorians considered such a vision of art and criticism to be sinful and irreligious. They were horrified by what they considered to be debauchery”.

Critics of Art for Art’s Sake

Many artists and intellectuals have challenged the notion that art should be evaluated purely on a set of discrete aesthetic or formal standards from the start. Academic artists disagreed with the Art for Art’s Sake movement because they argued that it lacked the moral significance that the Academy’s preferred classical topics provided. Certain aspects of this perspective are expressed in Ruskin’s critique of Whistler’s artwork. Art for art’s sake was derided by the new avant-garde movements in the arts, similar to how traditionalists condemned it, despite both movements being on the extreme opposite sides of the art spectrum.

In 1854, Gustave Courbet, the founder of Realism, widely regarded as the first modern art movement, intentionally made a distinction between his aesthetic philosophy and art for art’s sake and rejected the academy’s standards, portraying them as two opposing sides of essentially the same coin: “I was the sole judge of my artwork. In order to gain my intellectual independence, I had been practicing painting, not creating art for the sake of creating art”. Courbet’s perspective mirrored that of numerous other forward-thinking artists who believed, as author George Sand said in 1872, that “art for art’s sake is a meaningless term. That is the faith I seek: art for truth’s sake, art created for the sake of the beautiful and the good”.

Avant-Garde and Modernism art movements became more closely associated with the advancement of alternative political, social, and ethical values, rather than just a hedonistic disdain of academic and Victorian standards.

Art Movements Associated with Art for Art’s Sake

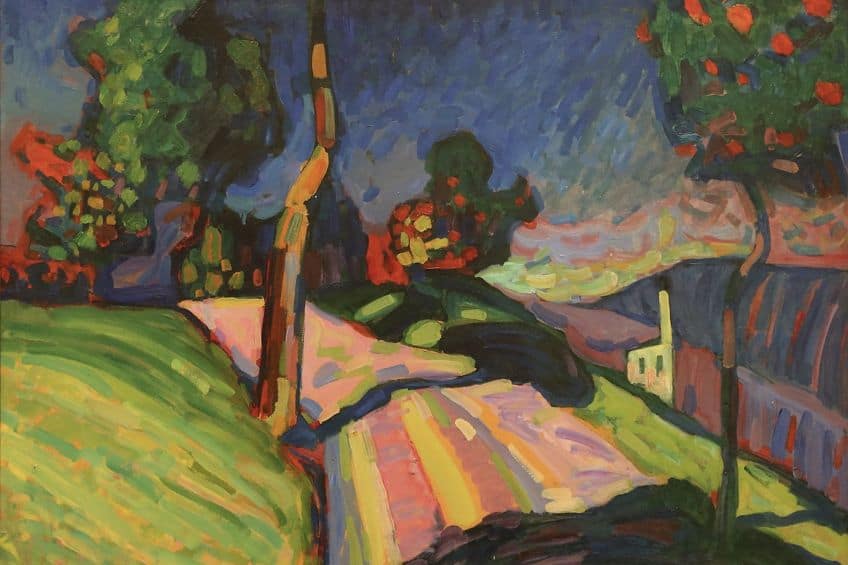

Benjamin Constant, the Swiss writer, is considered to have first used the term “art for art’s sake” in a diary entry from 1804. The concept was popularized among authors, largely thanks to Théophile Gautier, the novelist from France. James Abbott McNeill Whistler, the renowned artist from the States is often considered the forefather of the idea of art for art’s sake in the visual arts. Whistler’s stance that visual art should not be used for representing a certain theme led him to equate it to the abstract sphere of music. Whistler contributed to the development of both the Aesthetic movement and Tonalism by highlighting the significance of art for the sake of art.

The Aesthetic Movement

The Aesthetic movement had begun to emerge by 1860, based in the United Kingdom, and focused on the essential principles of art for art’s sake. The movement came to be associated with depictions of feminine beauty juxtaposed against the decadent nature of the classical world, as represented by the works of painters such as Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Albert Joseph Moore, who were influenced by Whistler’s pioneering work and Gautier’s critique. Aestheticism also intersected with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s worldview, which included Edward Burne-Jones, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Morris.

These artists became consumed by the “Cult of Beauty”, a concept significantly related to the principles of art for the sake of art that suggested that the formal force of the art piece was more important than anything else.

Yet, many Pre-Raphaelites, like Morris, were also involved in utopian politics, driven by an idealized view of medieval social institutions. This indicates that the concepts of art for art’s sake influenced a wider variety of artistic ideologies than is often assumed. Walter Pater rose to prominence as a strong proponent of Aestheticism. He remarked in his works that art comes to one offering openly to provide nothing but the finest qualities to one’s passing moments, merely for the sake of these moments.

In doing so, Pater broadened the idea to describe the sort of experience that someone looking at it should have from a certain artwork, instead of simply applying it to the intentions of the artist. Aubrey Beardsley, an illustrator, was also influential in the development of the Aestheticism movement. Beardsley’s editorship, drawings, and critical commentary in The Yellow Book, a literary journal published from 1894 to 1897, all had an impact on the formation of formalistic and Decadent tendencies around the turn of the century in Britain.

The Decadent Movement

Emerging in the 1880s, the Decadent movement flourished alongside the Aesthetic movement and shared its origins in the mid-19th century, with Beardsley playing an important role in both movements. The Decadent movement, though, was mostly associated with France, particularly with the artwork of Félicien Rops, a Belgian artist who lived in France. Rops was a contemporary of Charles Baudelaire, who proudly called himself a “decadent” in 1857, and the phrase grew to be associated with a rejection of 19th-century puritanism, dreariness, and sentimentality. Art for art’s sake, as defined by the Decadent movement, was an apparent rejection or mocking of the philosophies and societal positions for which art would have been expected to represent. The Decadents focused on the sexual, disturbing, and scandalous.

Beardsley’s illustrations in The Yellow Book were reported in the press to be laden with concealed erotic references, demonstrating his rejection of Victorian moralism.

Tonalism

Tonalism, which was mostly practiced in North America, had nothing to do with the scandal-seeking decadent nature of Beardsley and his contemporaries. The Tonalists, however, established a style that was equally dedicated to the concept of art for the sake of art, with their misty and glowing atmospheric landscapes. The Tonalism movement’s emphasis on delicate patterning, balanced design, and otherworldliness arose directly from the Aesthetic movement and the works and creative philosophies of art for the sake of art championed by its most prominent advocate, James McNeil Whistler.

He focused on mood and ambiance while experimenting with a simpler, almost abstract world in terms of color tonality. Tonalism, according to some art critics, was a collection of trends that began to converge about 1870, and was not really a unified movement. It stayed an unnamed style until the mid-1890s. Tonalism became a significant influence in American art, particularly in the work of North American artists Albert Pinkham Ryder and George Inness, in addition to Edward Steichen, the photographer.

Art for Art’s Sake’s Effect on Art History

Pater and Gautier’s intense critique affected not just the evaluation of contemporary artwork, but also of the classical and Renaissance artwork that preceded it. Rejecting the story-telling technique and ethical subject matter of classical history art, as illustrated by Raphael and celebrated by conventional academies, these two critics reexamined the works of artists like Botticelli.

Furthermore, according to Rochelle Gurstein, “while numerous authors associated with the Art for the Sake of Art movement in England and France paid enthusiastic respect to the artwork, Pater and Gautier have become most recognized for launching it on its current path to what is now inelegantly referred to as iconicity”.

Gautier emphasized the peculiar, almost magical allure that the Mona Lisa possesses for even the greatest skeptics. Pater dubbed the Mona Lisa “the emblem of the modern idea”, in a poetic statement that continues to shape our understanding of what the painting signifies. In fact, no one – from Bernard Berenson to Oscar Wilde – could speak of the painting without referring to Pater’s illuminated words, which many of them had committed to memory.

The Later Developments of Art for Art’s Sake

Following the controversy of Oscar Wilde’s trial, conviction, and incarceration in 1895 for homosexuality, the Aesthetic movement came to an end. Oscar Wilde’s fall from public grace largely discredited the Aesthetic Movement in the eyes of the people in general, but many of its concepts and forms persisted into the 20th century. With the demise of the Aesthetic movement, the expression “art for art’s sake” fell out of favor, yet it remained prominent in other countries. Léon Bakst, Sergei Diaghilev, and Alexandre Benois launched the periodical Mir Iskusstva in St. Petersburg in 1899. The journal was affiliated with the World of Art movement, which was founded the previous year by a group of young painters in St. Petersburg.

The organization, which promoted art for the sake of art and creative independence, undoubtedly had its biggest influence through the founding of the pioneering Ballets Russes, which Diaghilev formed in 1907 and managed until 1927.

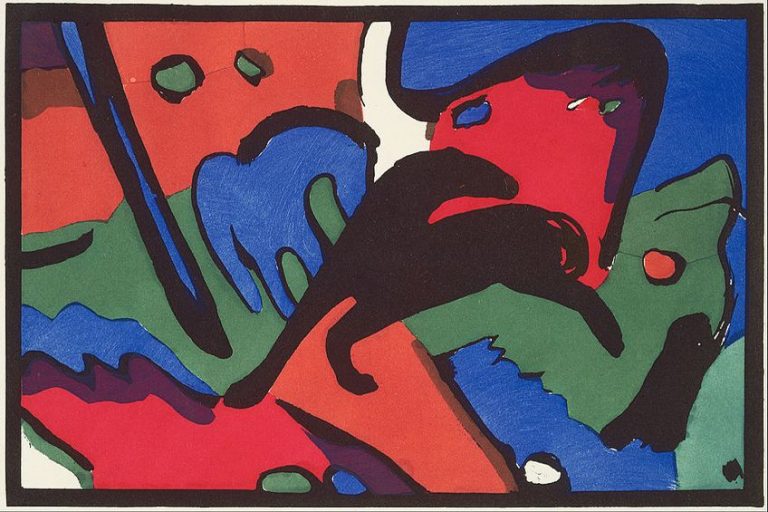

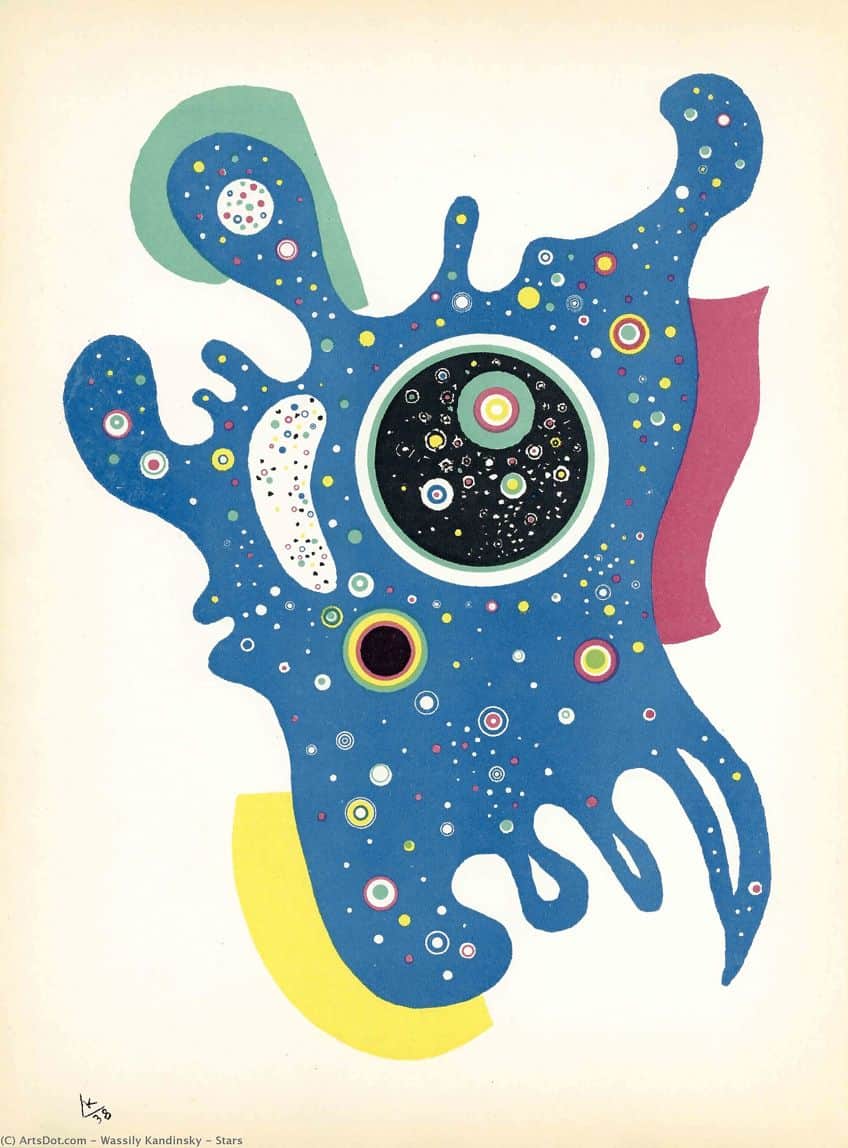

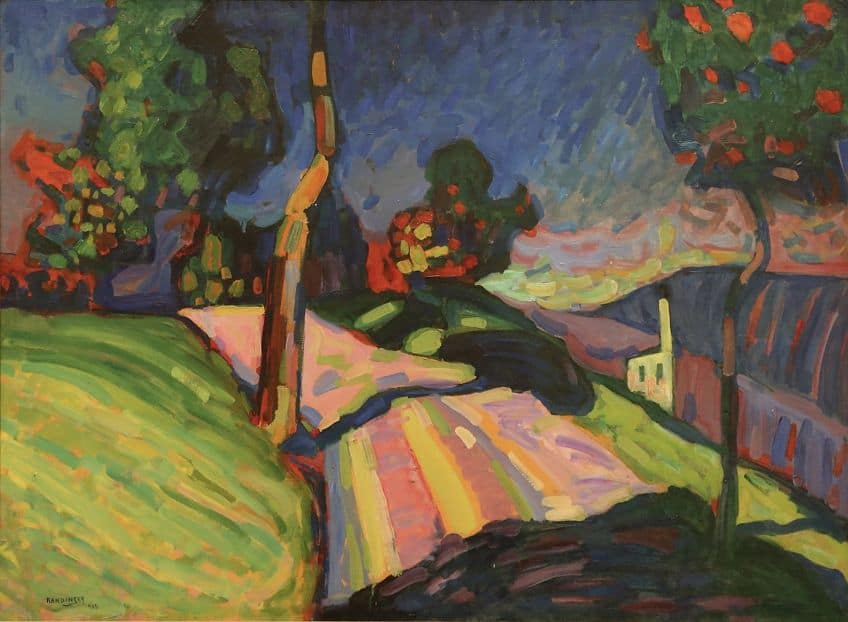

The concept of art for the sake of art had a significant, if sometimes counterintuitive, impact on avant-garde art. The avant-garde was not merely a rejection of art for the sake of art, but also in many senses a continuation of it. Many prominent 20th-century painters ignored it or derided it. Pablo Picasso declared that art for the sake of art was a deception, whereas Wassily Kandinsky argued that art for the sake of art refers to the disregard of underlying meanings, which is the life of colors, and the waste of artistic power.

Despite this, the idea was often greeted with ambiguity. To a certain extent, Kandinsky understood the idea, defining it as an inner reaction against materialism, against the requirement that everything must have a utilitarian function. Clement Greenberg, a famous art critic who advocated Abstract Expressionism after WWII, based his notions of media specificity and formalism on the foundations of art for art’s sake. As he established his idea of media specificity, Greenberg broadened the concept of art’s autonomy. According to historian Paul Bürger, the theory of art for the sake of art was an important factor in the emergence of avant-garde and modernist artworks.

He considered art autonomy to be a characteristic of bourgeois society. Pater’s style foreshadowed modernism. His impact lasted well into the 20th century, especially among notable critics and authors. Many literary critics were interested in Pater’s perspective as a predecessor to current theories of deconstruction during the postmodernism era. Aestheticism and modern deconstruction, according to scholars, developed comparable kinds of philosophical knowledge through the act of self-questioning, as well as internal critique and the disruption of hegemonic beliefs.

The Influence of Art for Art’s Sake in the Modern Era

The concept of appreciating art for its inherent characteristics was fundamental in the development of many movements in the 19th and 20th centuries. Notable art movements such as Symbolism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and Abstract Expressionism, welcomed the concept of art as a vehicle of personal expression and concentrated on examining the formal components of art. These movements stressed the importance of subjective interpretation and experimentation with new creative approaches to the aesthetic experience. It has additionally promoted the concepts of artistic independence and individuality in art.

Modern artists are free to follow their creative visions without any regard for external expectations or obligations.

This artistic liberation has resulted in the exploration of new concepts and materials and an erosion of established aesthetic limitations. The emphasis on aesthetic experience has become a major feature of modern art evaluation. Audiences are invited to interact with art on a far more personal level, examining their intellectual and emotional reactions. As a result, instead of depending on predetermined interpretations or messages, there is now an increased focus on the individual’s perception and experience of art.

Impact on Art Mediums and Art Theory

The idea of appreciating art for the sake of art has inspired artists to experiment with and push beyond the limits of their artistic mediums. As a result, new types of art such as installation art, performance art, video art, and digital art have emerged and flourished. These mediums typically value aesthetic enjoyment and exploration far more than the need for any practical purpose or social commentary.

This idea has spawned various theoretical debates regarding the nature and meaning of art.

It has prompted discussions regarding the importance of aesthetics, artistic autonomy, the connection between art and the society in which it was created, and the significance of artistic expression. The discourse around contemporary art has been fundamentally shaped by these conversations, and it still influences the way we make and critique art today.

Many British, French, and American authors, painters, and supporters of the Aesthetic movement, like Walter Pater, embraced the idea of art for the sake of art. It was seen as a vehement rejection of Victorian-era moralism, as well as the practice of art serving the official religion or state since the Counter-Reformation of the 16th century. The Impressionist movement and contemporary art movement were able to express themselves freely as a result of this change in direction. This idea arose in opposition to those who believed that the intrinsic value of art depended on having some moral objective. The idea of art for the sake of art is still relevant in today’s debates over censorship, as well as the nature of art in general.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Meaning of Art for Art’s Sake?

For much of art history, artworks were produced to serve a specific function in society. They tended to be produced to communicate certain religious and political ideals. The concept of art for the sake of art, however, revolves around the idea that art should first and foremost be created and appreciated for the sheer aesthetic pleasures of art. Many notable French and English authors embraced the idea that art required no justification, that it was not required to fulfill any specific purpose, and that the aesthetic appeal of the fine arts was more than enough reason for exploring them.

Is Art for the Sake of Art Still Relevant Today?

This concept changed the way people both produced and enjoyed art. Today, artists are able to create works that are not required to meet any specific criteria or advocate any specific idea. They can produce art for the pleasure of producing art, and it can be appreciated merely for its intrinsic aesthetic qualities. This is a huge departure from the time when artists were forced to produce work to fulfill commissions from the state or religious institutes. This effectively changed art from a means of spreading propaganda to an expression of the artist’s inner world.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Art for Art’s Sake – The Meaning of Art for its Own Sake.” Art in Context. July 10, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/art-for-arts-sake/

Meyer, I. (2023, 10 July). Art for Art’s Sake – The Meaning of Art for its Own Sake. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/art-for-arts-sake/

Meyer, Isabella. “Art for Art’s Sake – The Meaning of Art for its Own Sake.” Art in Context, July 10, 2023. https://artincontext.org/art-for-arts-sake/.