Pablo Picasso – The Life and Works of This Famous Cubism Artist

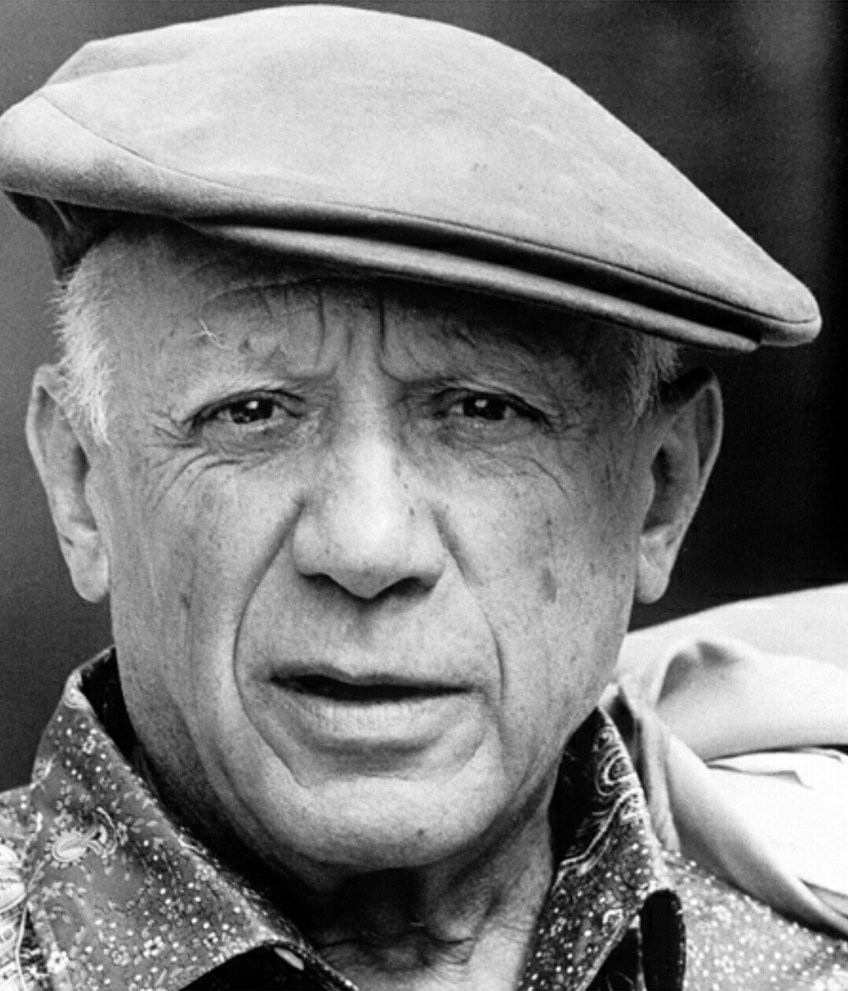

Pablo Picasso is perhaps the most influential figure in the history of 20th-century art. The varied range of Pablo Picasso’s artworks were not the result of drastic transformations in his style over his career but were instead based on his commitment to objectively evaluate the form and method best suited to accomplish his desired impact for each art piece. Picasso’s artworks were unquestionably destined to be interwoven into the tapestry of mankind as some of the finest artworks of all time.

Table of Contents

The Life and Art of Pablo Picasso

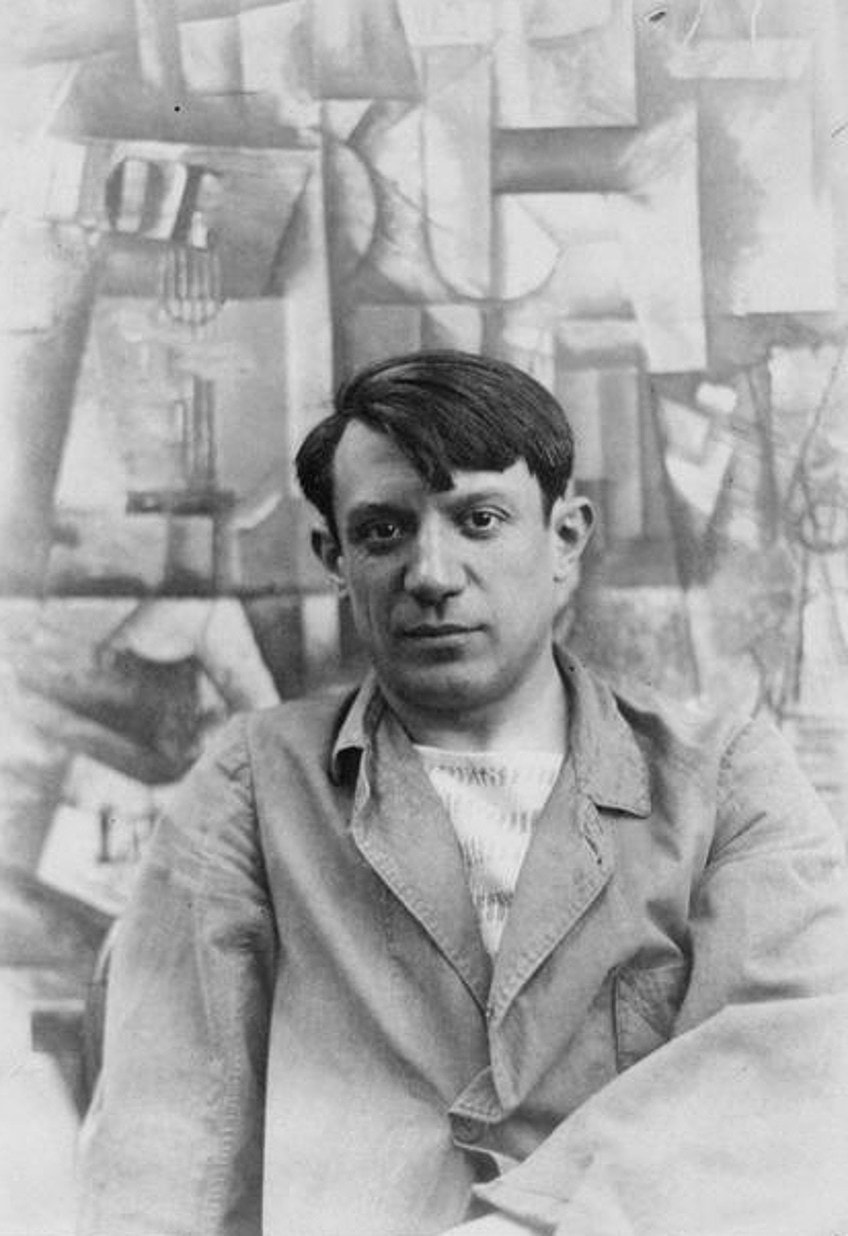

Before reaching the age of 50, this famous artist had established himself as the most renowned figure in contemporary art, with the most distinctive aesthetic and sense for artistic production. Before Picasso, no other creator had made such an influence on the art community or had such a significant reputation among admirers as well as critics.

During his lengthy career, Picasso’s drawings, paintings, and sculptures amounted to around 20,000 pieces, including other objects such as costuming and theatrical sets.

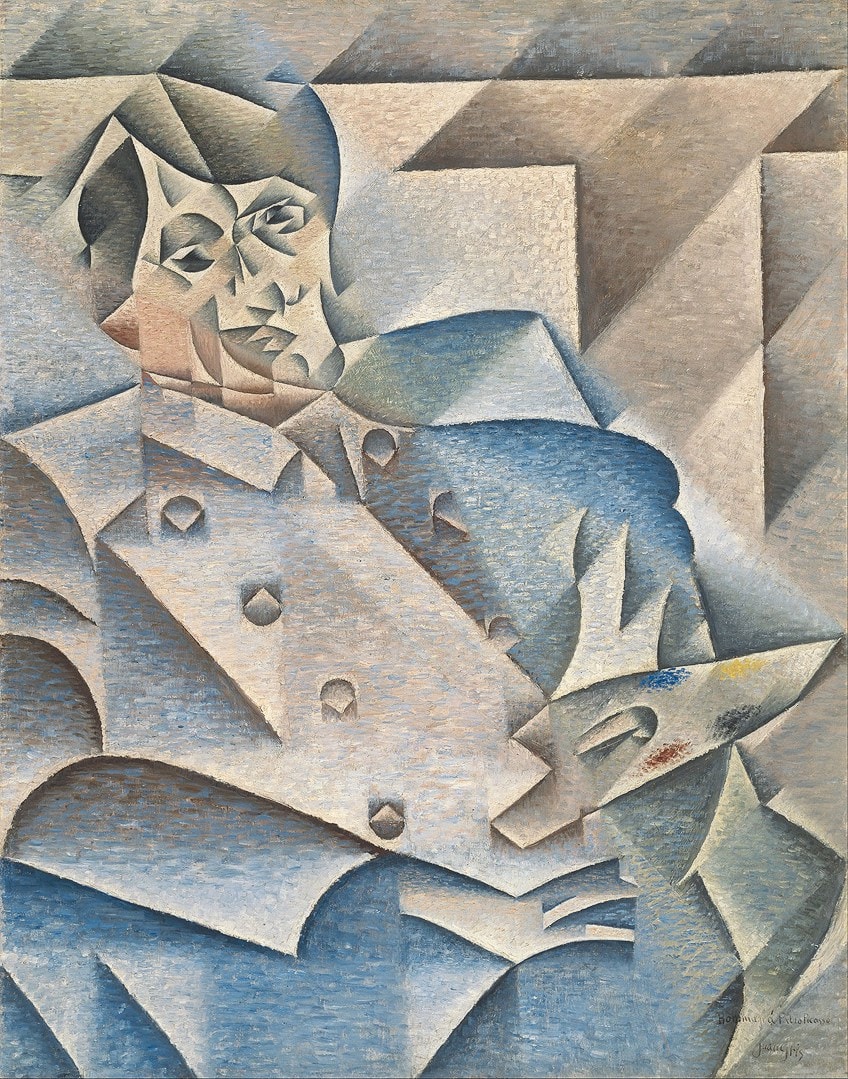

He is globally considered to be one of the 20th century’s most important and acclaimed painters. As an artistic pioneer, he is credited with being a founding member of the Cubist movement with Georges Braque. Cubism was a cultural movement that forever altered the landscape of European sculpture and painting, as well as architectural styles, music, and writing.

Cubist themes and artifacts are disassembled and reassembled in an abstract fashion.

When Picasso and Braque were creating the groundwork for Cubism in France between 1910 and 1920, its influence was so far-reaching that it inspired offshoots such as Dada, Futurism, and Constructivism in other nations. Picasso is also recognized for the invention of built sculpture and the co-invention of the collage art form. He is also considered among three 20th-century painters who are acknowledged for developing the principles of Plastic arts.

By actively manipulating substances that had not before been cut or sculpted, this innovative art form drove civilization toward social improvements in paintings, sculpting, printing, and pottery. These substances were not simply plastic; they could be shaped in some fashion, generally in three dimensions. Plaster, metals, and wood were employed by artists to produce groundbreaking sculptural artworks that the public had never experienced before.

But when was Picasso born and when did Picasso die? Let us first take a look at Pablo Picasso’s biography before we go any further into his style and examples of famous Picasso paintings.

Pablo Picasso’s Biography

Picasso’s propensity to create works in a wide range of genres earned him a high level of recognition throughout his lifetime. His importance as an artist and an influence on other painters has only risen since his death in 1973. To understand how he rose to fame, let us take a look at his childhood, education, and art periods.

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Date of Birth | 25 October 1881 |

| Date of Death | 8 April 1973 |

| Place of Birth | Malaga, Spain |

Early Life

Picasso was born to Don and Maria Picasso in Malaga, Spain. His father, an artist and art instructor, was awestruck by the young boy’s painting talent from a very early age. Picasso began academic training from his father at the age of seven.

Ruiz felt that instruction consisted of reproducing masterpieces and sketching the human figure from live subjects as well as plaster casts due to his conventional academic schooling.

When Picasso was ten years of age, his family relocated to A Coruna, where the School of Fine Arts employed his father as a lecturer. They stayed for four years, during which time Ruiz thought his son had overtaken him as a painter at the age of 13 and resolved to stop painting. Though Ruiz’s still created paintings for many years to follow, he was undoubtedly awed by his son’s inherent talent and skill. Pablo Picasso’s family was shocked when his little sister passed away in 1895 from diphtheria.

Early Training

They relocate to Barcelona, where Pablo Picasso’s father started working at the School of Fine Arts. He convinced administrators to allow his son to take an admission test for an expert class, and Picasso was enrolled at the age of 13 years old. When he was 16 years of age, he was admitted to the Royal Academy of San Fernando, Spain’s most prestigious art school. Picasso despised the formal lessons and dropped out of his lessons soon after arriving. He spent his days within Madrid’s Prado, which had works by El Greco and Goya.

Picasso’s corpus of work is extensive and extends from his early childhood years until his death, offering a more thorough record of his progress than possibly any other artist.

Studying the archives of his initial studies, there is reported to be a transition when the childlike aspect of his drawings faded, indicating the formal start of his profession. That year is claimed to be 1894 when young Pablo Picasso Would have been just 13 years of age. He produced the Portrait of Aunt Pepa at the age of 14, a remarkable picture that has been considered to be one of the greatest portraits in the history of Spain. Picasso also produced his award-winning Science and Charity at the age of 16. His realism method, which had been instilled in him by his father and early education, expanded with his exposure to symbolist ideas.

This inspired Picasso to create his own interpretation of modernity and to undertake his first journey to Paris.

Picasso learned French from a Parisian acquaintance, poet Max Jacob. They lived in an apartment where they learned what it was like to be a “struggling artist.” They were chilly and poor, and they had to burn their own works to keep the flat warm. Despite the fact that he started developing sculpture throughout this phase, critics refer to it as his Blue Period, named after the blue color palette that characterized his canvases.

The work’s tone was likewise unmistakably melancholy.

The artist’s anguish at the suicide of Carlos Casegemas, a friend he met in Barcelona, may be seen as the origins of this, while the themes of most of the Blue Period works were derived from the homeless and hookers he met on city streets. The Old Guitarist (1903) is an excellent illustration of this period’s subject material and aesthetic. Pablo Picasso’s colors started to lighten in 1904, and he worked in a manner known as his Rose Period for a year or longer. He concentrated on entertainers and circus people, changing his palette to more cheerful pinks and reds.

And, shortly after meeting artist Georges Braque in 1906, his palette deepened, his figures got denser and more concrete in appearance, and he started to move towards Cubism.

Mature Period

Previously, commentators traced the origins of Cubism to his early work Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). Although that piece is today regarded as intermediate (it lacks the dramatic aberrations of his later efforts), it was definitely pivotal in his growth due to its heavy influence from African sculptures and old Iberian artwork.

It is said to have motivated Braque to create his own first series of artworks, and in the years that followed, the two would embark on one of the most extraordinary collaborative efforts in contemporary art, occasionally excitedly learning from one another, occasionally attempting to surpass one another in their fast-paced and aggressive contest to advance.

During the development of this radical approach, Braque and Picasso met on a regular basis, and Picasso characterized himself and Braque as “two climbers bound together.” Multiple viewpoints on an item are shown concurrently in their common vision by being split and reorganized in splintered forms. Form and space were the most important aspects, and as a result, both painters limited their palettes to neutral tones, in stark contradiction to the brilliant colors employed by the Fauves before them.

Picasso would always cooperate with an individual or a collective, but as Braque historian Alex Danchev put it, Picasso’s “Braque phase” was “the most intense and productive of his entire career.”

Picasso hated the title “Cubism”, particularly as critics began to distinguish between the two main methods he was claimed to follow – Synthetic and Analytical. He considered his oeuvre as a whole. However, there is little question that his work changed after 1912. He became less preoccupied with depicting the arrangement of items in space and more interested in employing forms and motifs as cues to hint at their existence in a whimsical manner.

He invented the collage method, and from Braque, he learned the related papiers colles method, which included cutout sheets of paper in combination with parts of preexisting source materials. Due to its dependence on different references to an item in order to build the description of it, this phase has later come to be regarded as the “Synthetic” phase of Cubism.

Picasso used this approach to produce more decorative and humorous arrangements, and its versatility inspired him to continue using it far into the 1920s.

However, the artist’s growing interest in dance shifted his works to new areas about 1916. Meeting the writer, painter, and filmmaker Jean Cocteau motivated this in part. Through Cocteau, he managed to meet Sergei Diaghilev and went on to design several sets for the Ballets Russes. Picasso had been experimenting with classical themes for some years before allowing its full run in the early 1920s. His characters got a lot bigger and more imposing, and he often depicted them against the context of a Mediterranean Golden Age.

They have long been connected with the broader conservative tendencies of Europe’s so-called rappel a l’ordre, a period of art now defined as Interwar Classicism. In the mid-1920s, he was influenced by Surrealism, which caused him to rethink his career path. His art evolved into something more expressive, frequently aggressive or provocative. This moment in his career corresponds to the time in his private affairs when his relationship with ballerina Olga Khokhlova began to fall apart and he started a new affair with Marie-Therese Walter.

Undoubtedly, critics have frequently noted how modifications in Pablo Picasso’s paintings style often coincide with shifts in his intimate relationships; his relationship with Khokhlova stretched the years of his involvement in dance, and his subsequent moment with Jacqueline Roque is affiliated with his late stage, in which he had become fixated with his place in history alongside the Old Masters. In the late 1920s, he started working with Julio González, the sculptor.

This was his most major creative collaboration since working with Braque, and it resulted in welded metal artworks that were afterward immensely influential.

Political issues started to distort Picasso’s vision as the 1930s progressed, and continued to do so for some time. In 1937, he was inspired by the bombardment of people in the Basque village of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War to produce the picture Guernica. During World War II, he resided in Paris, and the German officials left him alone long enough for him to resume his work.

Nevertheless, the war had a significant influence on Picasso, since the Nazis took his Paris art collection and murdered some of his dearest Jewish friends.

Picasso created works in their honor, including sculptures made of harsh, rigid materials like metal in The Charnel House, a particularly horrific successor to Guernica (1945). Following the war, he became deeply active with the Communist Party, and numerous big films from this era, such as War in Korea (1951), demonstrate his newfound dedication.

Late Years and Death

During the 1950s and 1960s, Pablo Picasso concentrated on his own replicas of great works by artists such as Diego Velázquez, Nicolas Poussin, and El Greco. Picasso sought shelter from his stardom in his final years, marrying Jacqueline Rogue in 1961.

His later works were mainly portrait-based, with almost garish color palettes.

Critics have typically regarded them as inferior to his previous work, however, they have gained a more positive reception in recent decades. During this later phase, he also produced a large number of ceramic and metal sculptures. In 1973, he died of a heart attack in the south of France.

The Various Periods of Picasso’s Artworks

Picasso would spend most of his professional adult life in France. His work has been loosely split into periods of time during which he would completely develop complicated topics and sentiments in order to build a unified body of work. The first period was known as the Blue Period.

The Blue Period (1901-1904)

Picasso’s melancholy phase, during which he directly experienced hardship as well as the effects of deprivation on people around him, is marked by basically monochrome works in tones of blue and blue-green, only sometimes brightened by other colors. Picasso’s paintings from this time period portray starvation, prostitution, and portraits of friend Carlos Casagemas following his death, culminating in the dismal allegorical picture La Vie (1903). La Vie depicted his friend’s inner anguish in the face of a girlfriend he attempted to murder.

In considering Picasso and his Blue Period, journalist and writer Charles Morice famously remarked, “Is this alarmingly precocious youngster not destined to confer the sanctity of a masterwork on the unpleasant sensation of existence, the disease from which he appears to be suffering more than anybody else?”

The Rose Period (1904-1906)

According to the term, Picasso had a more cheerful era incorporating pink and orange colors and the lively worlds of circus performers and harlequins after achieving some level of progress and overcoming some of his despair. The artist then encountered Fernande Olivier, a bohemian painter who would also become his lover. She later appears in a few of these more positive works. Pablo Picasso was extremely well received by the art collectors Gertrude and Leo Stein. They were not only his main sponsors but Gertrude was also included in one of his most renowned paintings, Portrait of Gertrude Stein.

African Influences (1907-1909)

The Paul Cezanne exhibition staged at the Salon d’Automne one year after the creator’s death in 1906 was a watershed moment for Picasso. Though Picasso was acquainted with Cezanne before the retrospective, it was not until the exhibition that Picasso realized the full extent of his creative brilliance. Picasso discovered a model for distilling the fundamentals from reality in order to generate a coherent surface that conveyed the artist’s distinct perspective in Cezanne’s works.

Around the same period, the qualities of indigenous African sculpture began to have a strong effect on European painters.

Picasso’s first masterwork was Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Five nude ladies are depicted in the picture, with bodies composed of flat, fractured surfaces and faces influenced by African masks. A viciously angled cut of melon in the still life of fruit at the bottom of the picture hovers on an unnaturally raised tabletop; the confined space the characters inhabit appears to thrust forward in sharp fragments.

Picasso deviates from conventional European art in this work by incorporating Primitivism and abandoning perspective in lieu of a flat, two-dimensional image plane. It seemed as though the art world had fallen when Les Demoiselles d’Avignon first debuted. Form and presentation as we knew them were utterly discarded. As a result, it was dubbed “the most inventive painting in modern art history.”

Picasso discovered the freedom of expression apart from contemporary and traditional French influences with the new painting tactics he used, and he was able to pave his own path. Formal principles produced during this time paved the way for the Cubist period that followed.

Cubism (1909-1912)

Around 1907, Picasso was driven to give his figures more gravity and form by a convergence of influence ranging from Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne to ancient and tribal artwork. And they eventually led him to Cubism, in which he demolished the perspective standards that had characterized Renaissance painting. During this time period, the style established by Picasso and Braques employed mostly neutral tones and was centered on “breaking apart” items and “evaluating them” in terms of their forms.

Cubism, particularly the second variant known as Synthetic Cubism, had a significant impact on the evolution of the Western art world.

This phase’s works stress the integration, or synthesis, of shapes in the image. Color becomes increasingly significant in the forms of items as they get larger and more beautiful. Non-painted things, such as newspapers or cigarette wrappers, are regularly glued on the canvas alongside painted regions – the inclusion of a wide range of superfluous materials is especially linked with Picasso’s revolutionary collage method. This collage approach highlights texture contrasts and raises the question of what constitutes truth and illusion in painting.

Picasso impacted the course of art for future generations through his use of color, form, and mathematical figures, as well as his unique method of depicting subjects.

Neoclassicism (late 1910s-early 1920s) and Surrealism (mid-1920s)

Picasso made his first journey to Italy in 1917, with an unrivaled command of technique and talent, and immediately began a phase of homage to neoclassical style. Breaking away from severe modernism, he created drawings and paintings evocative of Ingres and Raphael. This was only a prologue to Picasso appearing seamlessly combining his modernist thoughts with his abilities into surrealist masterpieces like Guernica (1937), a frenetic and powerful blend of style that depicts war’s desolation.

“Guernica” is often regarded as modern art’s most devastating anti-war message.

It was done to demonstrate Picasso’s support for the conclusion of the war and his overall denunciation of Nazism. Picasso chose not to depict the tragedy of Guernica in realism or romantic terms from the start. Key characters, such as a lady with extended arms, a bull, and an agonizing horse, are polished in drawing after sketch before being transferred to the expansive painting, which he also remodels multiple times. The somber color scheme and monochromatic theme were utilized to portray the difficult times and the sorrow that was being felt. Guernica questions the heroic nature of the battle and shows it as a horrific act of self-destruction.

The work was not only a functional report or painting, but it also remains a potent political image in modern art, surpassed only by a few frescos by Mexican artist Diego Rivera.

Famous Picasso Paintings

Pablo Picasso’s involvement in Cubism resulted in the growth of collage, in which he rejected the concept of the image as a window on items in the world and started to think of it just as an assemblage of signals that employed various, often metaphorical, techniques to relate to those things. This, too, would have far-reaching consequences for future decades.

Picasso had a diverse attitude to form, and while his work was typically defined by a single dominating approach at any one moment, he frequently moved alternately between multiple styles – occasionally even within the same piece.

His experience with Surrealism influenced not just the delicate shapes and gentle sensuality of pictures of his girlfriend Marie-Therese Walter, but also the sharply jagged iconography of Guernica (1937), the century’s most recognized anti-war artwork. Picasso was always keen to establish himself in history, and some of his most famous pieces, such as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), allude to a plethora of previous antecedents – even while subverting them.

As he grew older, he became increasingly concerned with ensuring his legacy, and his later work is distinguished by a candid discussion with Old Masters.

The Soup (1903)

| Date Completed | 1903 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 38 cm x 46 cm |

| Location | Art Institute of Chicago |

The Soup exemplifies Picasso’s Blue Period’s dark sadness, and it was created at the same time as a succession of other paintings devoted to themes of deprivation, aging, and disability. The artwork expresses Picasso’s worry about the deplorable situations he experienced while growing up in Spain, and it was undoubtedly inspired by the religious artwork he grew up with, particularly El Greco. Yet, the artwork represents the broader Symbolist trend of that time.

Picasso eventually regarded his Blue Period works as “nothing except feeling”; reviewers typically sided with him, despite the fact that many of these images are classic and, of course, quite expensive.

https://youtu.be/pQYJqqoR59c?t=95

Portrait of Gertrude Stein (1905)

| Date Completed | 1905 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 100 cm x 83 cm |

| Location | Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Gertrude Stein was Picasso’s author, personal friend, and even patron, and she was essential in his development as an artist. This picture, in which Stein is dressed in her beloved brown velvet coat, was completed barely a year before Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, and it represents a significant step in his maturing style.

In comparison to the flat look of several of the Blue and Rose period paintings, the shapes in this portrait appear nearly carved, and they were inspired by the creator’s study of antique Iberian sculpture.

Picasso’s heightened interest in representing a human face as a sequence of flat planes is practically palpable. Stein said that she sat for Picasso 90 times, and while this may be a hyperbole, Picasso undoubtedly struggled for a long time with portraying her head. After attempting it in numerous ways and failing, he painted it out completely one day, claiming, “I can’t perceive you anymore when I look,” and eventually abandoned the image.

He didn’t finish the head until much later, but without the subject in front of him.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907)

| Date Completed | 1907 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 243 cm x 233 cm |

| Location | Museum of Modern Art |

This artwork astounded even Picasso’s dearest artist colleagues, both in terms of content and technique. The theme of naked females was not uncommon, but Picasso’s portrayal of the girls as prostitutes in blatantly sexual attitudes was novel. Picasso’s fascination with Iberian and indigenous artwork is especially obvious in the mask-like faces of three of the females, hinting that their sexuality is not just violent but also primal.

Pablo Picasso also took his spatial explorations a step further by discarding the Renaissance impression of three-dimensionality in favor of presenting a dramatically flattened image plane split up into geometric fragments, a technique Picasso adopted partially from Paul Cézanne’s brushwork.

For example, the leg of the lady on the left is painted as though seen from many perspectives at the same time; it is difficult to discern the leg from the negative space surrounding it, giving the impression that the two are both in the forefront.

When the picture was ultimately shown in public in 1916, it was largely regarded as immoral.

Braque was one of the few painters who studied it thoroughly in 1907, which led straight to his Cubist partnerships with Picasso. Because Les Demoiselles foresaw several of Cubism’s traits, the work is regarded as proto- or pre-Cubism.

Still Life with Chair Caning (1912)

| Date Completed | 1912 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 29 cm x 37 cm |

| Location | National Gallery, London |

This famous artwork is regarded as the earliest collage in modern art. Picasso had previously attached pre-existing items to his paintings, but this is the first occasion he did so with such a humorous and dramatic aim. The chair caning in the image is made of printed oilcloth, not genuine chair caning, as the title implies.

The rope wrapped around the canvas, on the other hand, is extremely genuine and helps to mimic the carved border of a café table.

Moreover, the spectator can think of the canvas as a glass table, and the chair caning as the actual seat of the chair as perceived through the table. As a result, the image not only contrasts visual space significantly, as is characteristic of Picasso’s experimentation, but it also distorts our perception of what we are looking at.

Bowl of Fruit, Violin and Bottle (1914)

| Date Completed | 1914 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 92 cm x 73 cm |

| Location | National Gallery, London |

This piece is representative of his Synthetic Cubism, in which he employs numerous techniques to allude to the portrayed things, such as painted dots, shadows, and grains of sand. This paint and mixed media combo is an instance of how Picasso “synthesized” texture and color – inventing wholes after cognitively dissecting the items at hand.

Picasso repressed color during his Analytic Cubist period in order to focus more on the shapes and dimensions of the objects, and this logic certainly informed his predilection for still life all through this period.

The café life undoubtedly summarized modern Parisian life for the painters – he spent a lot of time there conversing with other painters – but the basic array of things also guaranteed that concerns of metaphor and reference could be kept in check.

Ma Jolie (1912)

| Date Completed | 1912 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 100 cm x 64 cm |

| Location | Museum of Modern Art |

Picasso explores the boundary between high art and common culture in this painting, pushing his experimentation in new areas. Picasso progresses towards abstraction by diminishing color and heightening the illusion of low-relief sculpture, expanding on the geometric outlines of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Picasso, on the other hand, incorporated painted text on the canvas.

The phrase “ma Jolie” on the cover not only condenses the space more but also links the artwork to a billboard due to their use of an advertisement font. It’s the first instance a painter has publicly utilized elements of popular culture in the creation of high art.

“Ma Jolie” was also the title of a popular tune at the time, as well as Picasso’s nickname for his girlfriend, further tying the painting to popular culture.

The Three Musicians (1921)

| Date Completed | 1921 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 204 cm x 188 cm |

| Location | Philadelphia Museum of Art |

There were two versions of Pablo Picasso’s paintings of the musicians. The somewhat smaller version is on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, although both are exceptionally enormous for Picasso’s Cubist phase, and he may have decided to create on such a huge scale to commemorate the end of his Synthetic Cubism, which had preoccupied him for over a decade.

He created it during the same summer that he created the extremely dissimilar, classical picture Three Women in the Spring. Some have regarded the images as nostalgic reminiscences of Picasso’s early days; Picasso sits in the middle, as always, the Harlequin, with old acquaintances Guillaume Apollinaire and Max Jacob, from whom he had been alienated, on each side.

Three Women at the Spring (1921)

| Date Completed | 1921 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 204 cm x 174 cm |

| Location | Museum of Modern Art |

Picasso performed extensive research in preparation for painting this, his most elaborate depiction of an old classical theme. It pays homage to older works by Poussin and Ingres, two titans of classical painting, but it also borrows cues from Greek sculpture, and the figures’ tremendous weight is quite sculptural.

Critics say that the topic attracted him due to the birth of his first son, the figures’ solemn demeanor may be understood by France’s current obsession with remembering the First World War’s deceased.

Guernica (1937)

| Date Completed | 1937 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 250 cm x 777 cm |

| Location | Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía |

Picasso painted this painting in response to the shelling of Guernica, a Basque village, on the 26th of April, 1937, amid the Spanish Civil War. It was finished in one month and functioned as the focal point of the Spanish pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris.

While it made quite a commotion during the exhibition, it was subsequently barred from being shown in Spain until the deposition of militaristic tyrant Francisco Franco in 1975.

Much work has been spent deciphering the artwork’s significance, and some feel that the suffering horse in the middle of the canvas relates to the citizens of Spain. The minotaur may refer to bullfighting, a popular national pastime in Spain, but it also has a profound personal meaning for the artist.

Although “Guernica” is without a question Modern art’s most iconic reaction to conflict, critics have been split on the painting’s impact.

Recommended Reading

Pablo Picasso’s biography is a detailed and long journey. It is not always possible to fit every bit of information into an article. Perhaps you are keen to explore Picasso’s drawings and paintings even more in your own time. Here you can find more info on Pablo Picasso’s paintings and life.

Life with Picasso (2019) by Francois Gilot

Françoise Gilot’s honest book is the most comprehensive picture of Picasso ever published, providing an intriguing insight into the emotional and creative lives of two modern artists. In 1943, Françoise Gilot was in her early 20 when she met Pablo Picasso, who was 61 at the time. Born from an upper-middle-class household who had the expectation that she would become a lawyer, the young woman disregarded her parents’ desires and pursued a career as an artist. She was one of Picasso’s muses, but she was rather much her own person, driven to become the extraordinary painter she eventually became.

- The most revealing portrait of Pablo Picasso ever written

- Get fascinating insight into the two artist's intense and creative lives

- A brilliant self-portrait of a young woman of enormous talent

Picasso: Painting the Blue Period (2021) by Kenneth Brummel

Advanced technology exposes hidden compositions, themes, and modifications, as well as previously undisclosed information on the creator’s materials and method, providing new insights into Picasso’s Blue Period. This multidisciplinary book integrates art history and advanced preservation science to demonstrate how the young Picasso crafted a unique look and a distinguishable artistic identification as he evolved the artistic instruction of fin-de-siècle Paris to the political situation of a troubled Barcelona.

Picasso’s proclivity to create works in a variety of genres gained him widespread acclaim throughout his career. Let us conclude this article with a few more famous Picasso quotes to get a glimpse inside this quirky and creative artist’s mind: “Every youngster has the potential to be an artist. The issue is how to stay an artist as he grows older.” and “I’m always doing what I can’t do so that I can discover how to do it.”

Frequently Asked Questions

When Was Picasso Born and When Did Picasso Die?

Pablo Picasso was born into a creative family on the 25th of October 1881. He was born in Spain, in the city of Malaga. In 1973, he died of a heart attack in the south of France.

Who Was Pablo Picasso?

Picasso spent most of his professional adult life in France. His work has been roughly divided into time periods in which he would totally develop complex ideas and feelings in order to create a coherent body of work. The first phase was referred to as the Blue Period. The diverse spectrum of Pablo Picasso’s artworks was not the product of significant changes in his style during his career, but rather of his devotion to objectively evaluating the form and approach best suited to achieve his intended effect for each art piece.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Pablo Picasso – The Life and Works of This Famous Cubism Artist.” Art in Context. March 2, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/pablo-picasso/

Meyer, I. (2022, 2 March). Pablo Picasso – The Life and Works of This Famous Cubism Artist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/pablo-picasso/

Meyer, Isabella. “Pablo Picasso – The Life and Works of This Famous Cubism Artist.” Art in Context, March 2, 2022. https://artincontext.org/pablo-picasso/.