Ukiyo-e – A Glimpse into Japan’s Pictorial History

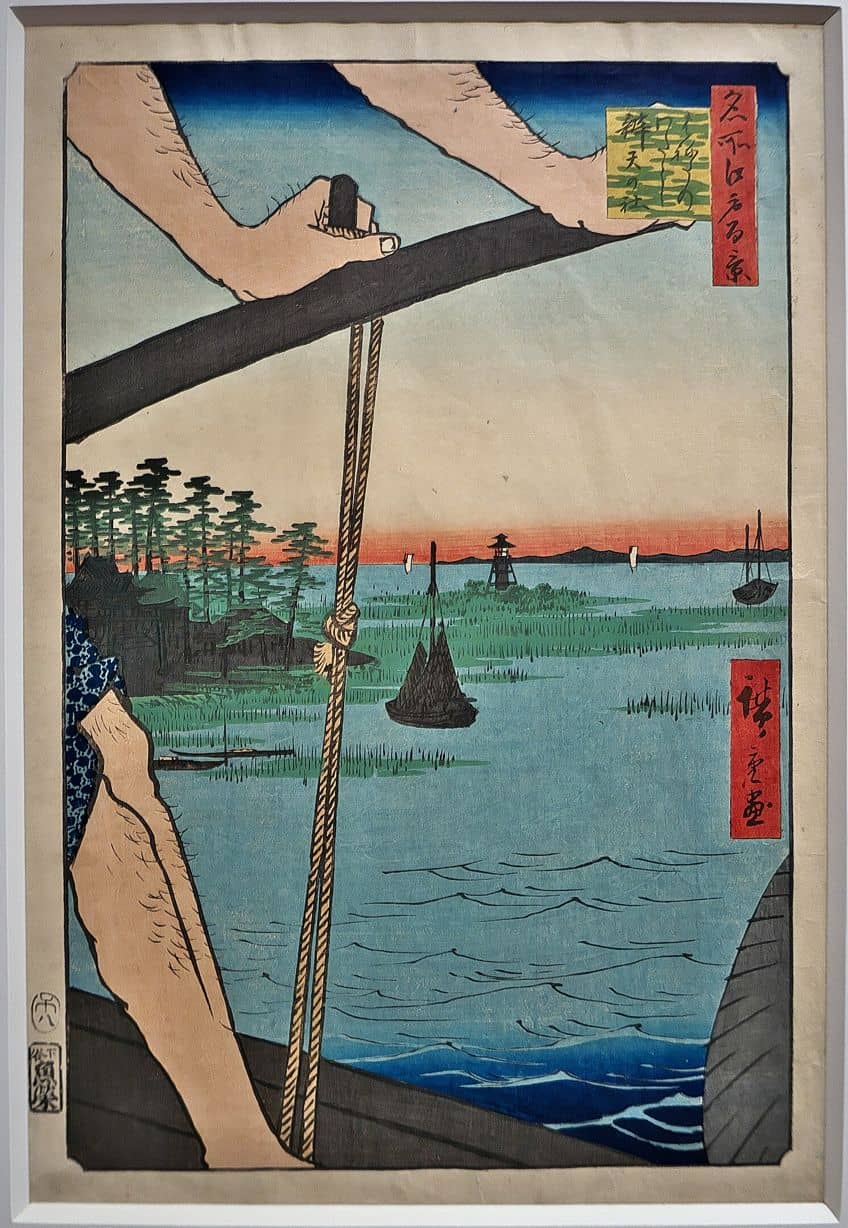

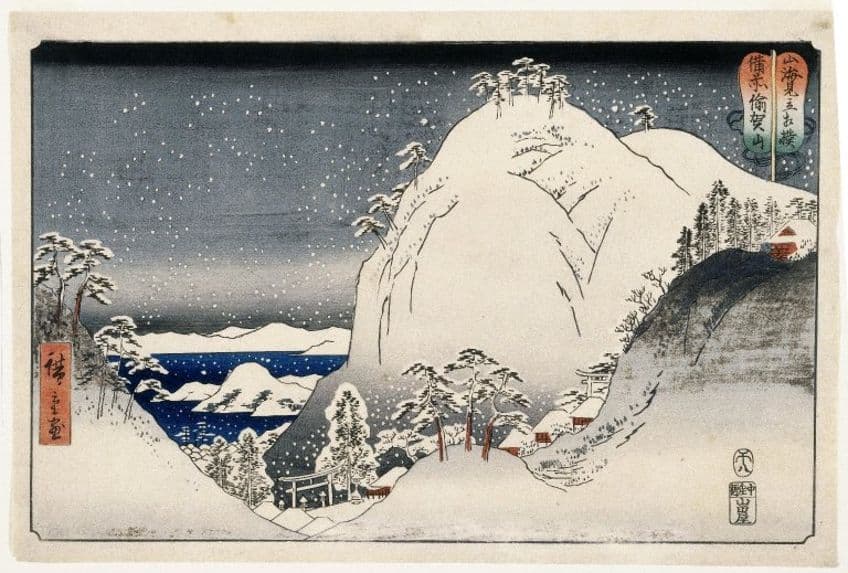

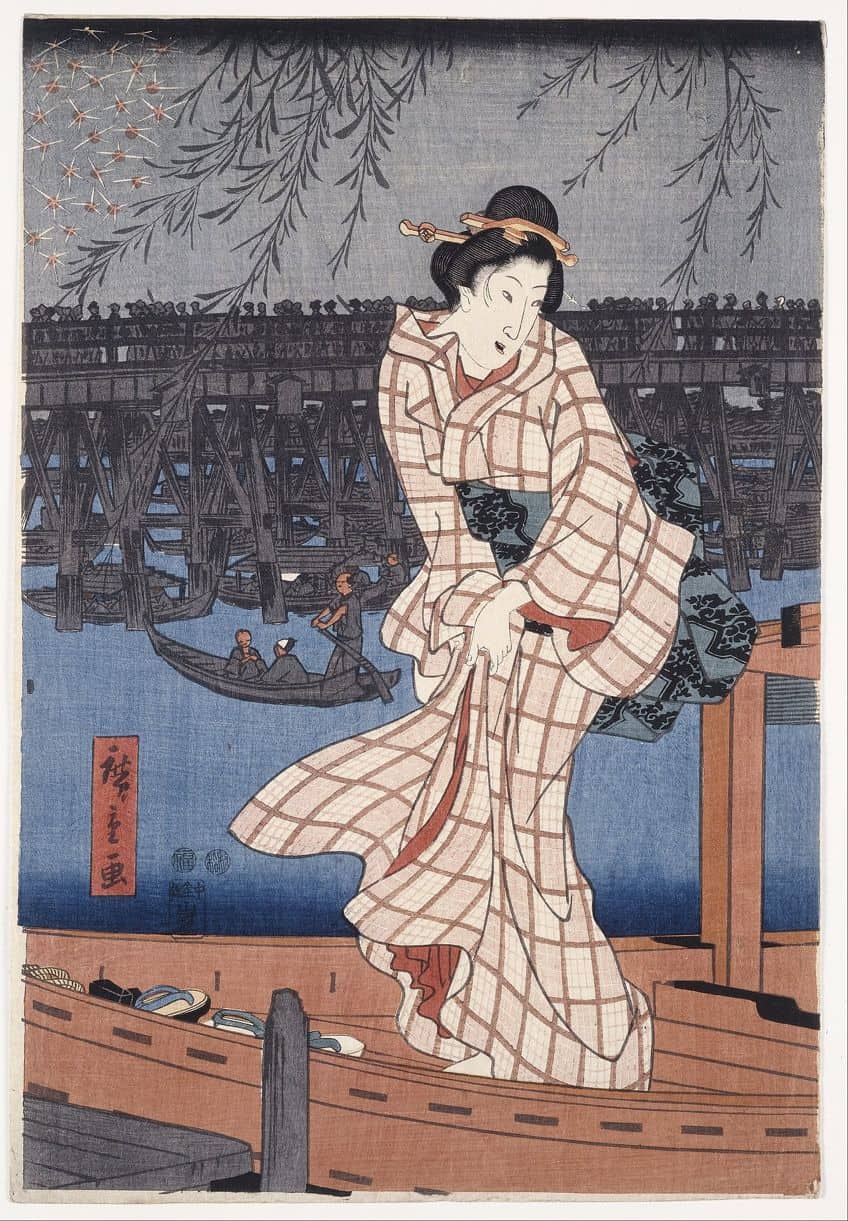

Ukiyo-e, a genre of Japanese woodblock prints originating in the Edo period (1603 – 1868), captures the essence of the “floating world” with its vibrant depictions of urban culture, theater, beauty, and nature. Literally translating to “pictures of the floating world,” ukiyo-e emerged as a popular art form, reflecting the dynamic and ephemeral aspects of life in bustling Edo (modern-day Tokyo). Artists like Hokusai, Hiroshige, and Utamaro elevated ukiyo-e to an esteemed position, shaping its aesthetic and thematic contours. Through meticulous craftsmanship and innovative techniques, ukiyo-e prints offer a captivating window into the societal transformations, aesthetic sensibilities, and narratives of Japan’s past, making them not only artistic treasures but also invaluable historical and cultural artifacts.

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- Ukiyo-e represents a crucial era of Japanese art from the 17th to the 19th centuries.

- The art form encapsulates the transient lifestyle and culture of Edo-period Japan.

- Ukiyo-e involved an evolution from simple prints to complex polychromatic art, featuring profound social and historical influences.

Historical Context and Evolution

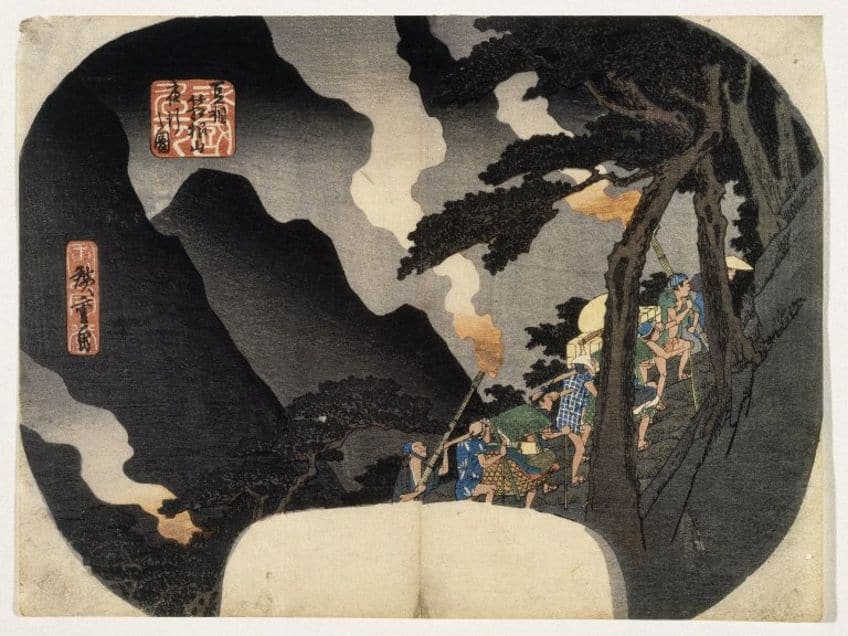

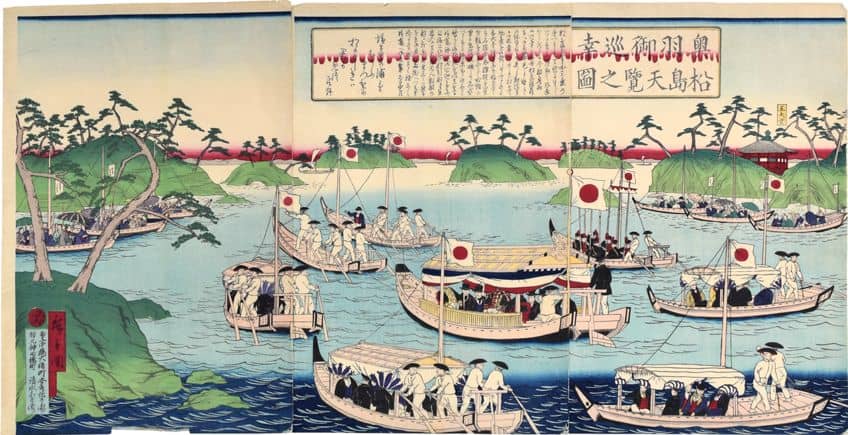

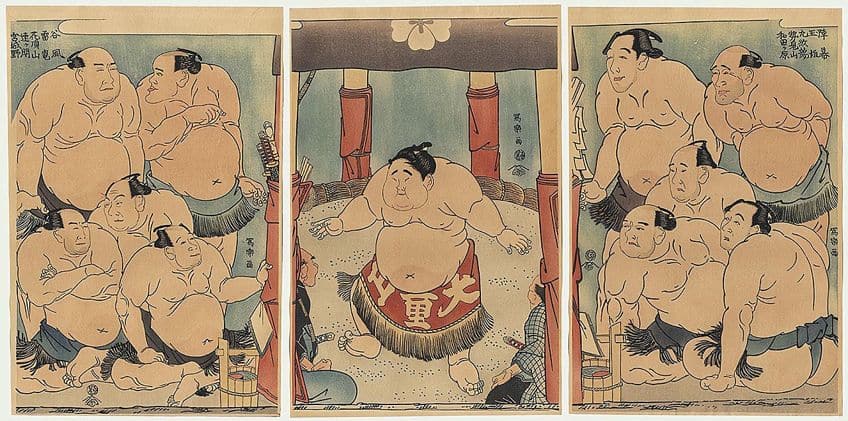

Ukiyo-e is a distinctive form of Japanese art that became especially popular from the 17th to the 19th centuries, shaping the aesthetics of Japan’s Edo period. This genre is characterized by woodblock prints and paintings that feature a wide variety of themes. Common subjects include female beauties, kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, historical scenes, folk tales, landscapes, and more, providing a vivid portrayal of the period’s culture and indulgences.

Artists during this time developed their own styles and techniques, which led to the evolution of ukiyo-e from simple monochromatic designs to sophisticated prints with multiple colors. The term ‘ukiyo-e’ itself translates to ‘pictures of the floating world’ and reflects the transitory nature of the hedonistic lifestyle depicted in the art. As these pieces captured moments of fleeting beauty and enjoyment, they were well sought after by the middle classes.

They served as a reflection of their aspirations and interests.

Origins and Early Development

Ukiyo-e emerged in the Edo period (1603 – 1868), influenced by the realistic narratives of earlier Heian period emaki and decorative styles of the Momoyama period. Early works centered around ukiyo, which referred to the transient nature of life, encapsulating everyday life, pleasure quarters, and the beauty of nature.

Golden Age and Artistic Development

The Golden Age of ukiyo-e is marked by the Kanbun era to the late 18th century, with artists like Harunobu and Utamaro refining the art form. Complex color prints, known as nishiki-e, were developed.

These were known for depicting vibrant scenes of kabuki actors, samurai, geisha, and everyday Edo (present-day Tokyo) life.

Late Edo and Transition to Meiji

In the late Edo period, masters like Hokusai and Hiroshige expanded ukiyo-e to include landscapes and nature. The art form experienced changes as the Tokugawa regime fell, leading to the Meiji period, where ukiyo-e inspired Western impressionists and began the transition to modern Japanese woodblock prints.

Cultural Significance and Influence

Ukiyo-e captured aspects of Buddhist philosophy and flourished under the shōgun’s patronage. The artwork portrayed the transient world, from the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters to Buddhist texts.

They influenced various cultural expressions, including literature and theater.

Preservation and Global Recognition

Important ukiyo-e collections are preserved in institutions such as the Library of Congress and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History and Edo: Art in Japan, 1615 – 1868 offer insights into the vast historical reach and recognition of ukiyo-e across the world.

Artistic Techniques and Production

The production of ukiyo-e woodblock prints is a complex process involving skilled artists, carvers, and printers. It requires precision and collaboration, and has evolved to include various innovations and stylistic elements.

These greatly influencing the aesthetics of Japanese art.

The Woodblock Printing Process

The traditional method of creating ukiyo-e prints begins with the artist making a detailed design on paper. This sketch is pasted onto a block of cherry wood, often the wood of choice for its fine grain and durability. A carver then meticulously chisels the design into the wood to create the carved block. For polychrome prints, known as nishiki-e, multiple blocks are carved for each color. Key steps in the woodblock printing process included:

- Design: An artist creates the initial artwork.

- Carving: Carvers transfer the design onto woodblock.

- Inking: Each block is inked with specific pigments.

- Printing: Paper is pressed onto the inked blocks, often by hand.

- Registration: Careful alignment, or registration, is crucial for multi-block color prints.

Materials and Craftsmanship

Printmakers traditionally used natural materials such as sumi ink, various pigments for color, and washi paper or silk. The pigments provide a wide range of vivid colors, key to the visual allure of ukiyo-e. Ink and color quality, along with the skill of the printer, greatly affect the final artistic work.

The materials used included:

- Paper: Washi paper derived from mulberry bark.

- Ink: Sumi ink for outlines and details.

- Pigments: Natural and synthetic pigments for coloration.

- Wood: Blocks often made from cherry wood.

Iconography and Themes

Ukiyo-e prints commonly depict the world of the ukiyo, or “floating world”, symbolizing the ephemeral nature of life. Imagery includes kabuki actors, courtesans, and vibrant scenes of urban life, as well as tranquil landscapes, historical narratives, and folk tales. Themes cover a spectrum from everyday activities to the pleasurable pursuits in the entertainment districts of Edo (modern-day Tokyo). Common ukiyo-e themes were:

- Portraiture: Actors, courtesans, and notable individuals.

- Scenery: Landscapes and famous places in Japan.

- Nature: Depictions of flora and fauna.

- Narratives: Scenes from literature, mythology, and everyday life.

Innovation and Stylistic Elements

Artists such as Hishikawa Moronobu, Okumura Masanobu, and Sharaku contributed to the development of stylistic elements and techniques. Innovations included the introduction of perspective, enhanced color schemes, and the use of mica and other substances to add texture and shimmer to prints. The aesthetic impact of ukiyo-e is seen in its balance of form, use of line, and juxtaposition of colors.

Stylistic innovations included:

- Perspective: Western and Eastern perspectives were explored.

- Color use: Advances in pigment technology led to richer, more varied color palettes.

- Embellishments: Use of embossing, metal inlays, and other techniques for visual effect.

Conservation and Reproduction

Conservation of ukiyo-e prints requires attention to the condition of the paper and pigments affected by light, moisture, and temperature. Reproductions of historical ukiyo-e are created using the same or similar techniques, often serving as important tools for study and preservation of the art form. Modern techniques can also involve digital imaging and printing methods. Conservation practices included:

- Environment: Controlled temperature and humidity for storage.

- Restoration: Careful cleaning and repair by conservators specialized in paper and pigments.

- Reproductions: Handmade or digital, they enable broader appreciation and analysis.

Socioeconomic Aspects and Market

Ukiyo-e, reflective of Edo period Japan, thrived on a robust market driven by merchants and a burgeoning consumer culture. This mass-produced art form was deeply intertwined with the socioeconomic fabric.

The artworks catered to a society fascinated by the floating world’s fleeting pleasures.

Patronage and Consumer Culture

During the Edo period, chōnin was the term for the wealthy merchant class whose patronage largely supported ukiyo-e artists. These merchants engaged in conspicuous consumption as a way to showcase their wealth and social standing, as their status was not in line with the conservative values imposed by the samurai-led government. The pleasure districts and theaters of Edo (now Tokyo) fueled the demand for woodblock prints, depicting scenes of kabuki actors, courtesans, and city life.

Ukiyo-e Artists and Publishers

Ukiyo-e artists often worked in close collaboration with publishers who were the financial and organizational backbone of the printmaking process. Renowned artists like Hokusai and Hiroshige gained fame through their prints, capturing landscapes and urban scenes popular among the masses.

Publishers facilitated the production and distribution, managing the intricate carvings on cherry wood blocks for mass replication of prints.

Representation of Social Classes

The art of ukiyo-e offered a visual manifestation of the Edo period’s social hierarchy. Artisans, prostitutes, and merchants were frequently portrayed, offering a contrast to the lives of the samurai and farmers. Prostitutes from brothels and depictions of the licensed quarters represented a slice of the floating world that was otherwise socially sanctioned but visually celebrated.

Historical Narratives and Popular Tales

Ukiyo-e prints often told stories of historical events, folklore, and provided a medium for circulating popular tales. Heroes from Japanese legends, monsters, and demons, alongside scenes of romantic vistas and landscapes were common subjects.

These narratives resonated with the print-buying public, who were eager to engage with tales that captured the imagination and reflected societal values and interests.

Influential Ukiyo-e Works and Artists

Ukiyo-e, a traditional Japanese art form, has seen numerous artists who have significantly influenced both the genre and art beyond Japan’s shores. This section examines key artists, their renowned works, and ukiyo-e’s transition to contemporary media.

Key Figures and Their Contributions

- Katsushika Hokusai: Often deemed a master of ukiyo-e, Hokusai is best known for his woodblock print series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (c. 1830 – 1832), which includes the iconic The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1831). Hokusai’s influence extends to his impact on the European Impressionist movement.

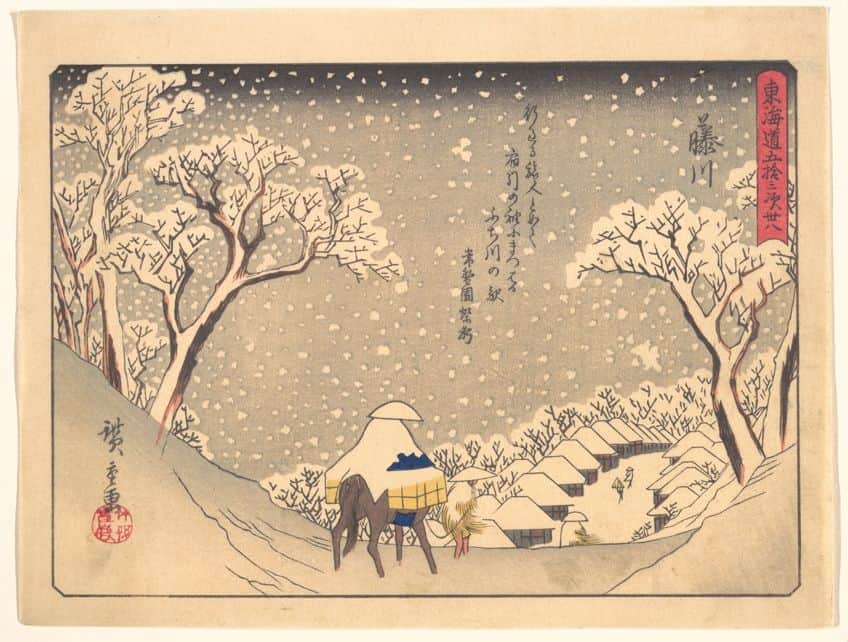

- Utagawa Hiroshige: Credited with pushing the boundaries of ukiyo-e landscape art, Hiroshige’s The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (1833 – 1834) series is celebrated for its unique perspective and masterful use of color.

- Toshusai Sharaku: Known for his kabuki actor prints, Sharaku brought forth the dramatic expressions and poses of Japan’s traditional theatre through his works.

Notable Works and Series

- The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1831) by Hokusai: This print, which captures the force of nature juxtaposed against Mount Fuji, is emblematic of the power and beauty central to ukiyo-e art.

- Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (1833 – 1834) by Hiroshige: It illustrates the scenic views along the Tōkaidō road, from Edo to Kyoto, and is revered for its landscape portrayal in Japanese printmaking.

Legacy of Ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e’s impact extends beyond its origins in Japan, influencing art and culture globally. It has shaped genres and aesthetics far removed from its Edo period roots. There are many ways that ukiyo-e influences modern culture.

These include:

- Manga: The art form of manga can trace its roots back to ukiyo-e, with Hokusai even using the term for his sketchbooks, which later influenced the manga style.

- Modern interpretations: Artists like Hasui Kawase played a role in the 20th-century revival with landscapes that melded traditional subjects with modern sensibility, bridging historical and contemporary art.

After Ukiyo-e Prints

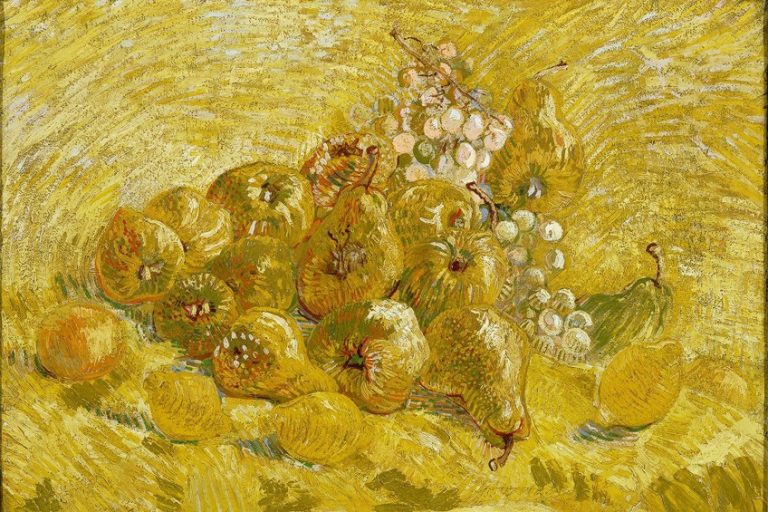

Ukiyo-e, or “pictures of the floating world,” represents a significant artistic movement originating during Japan’s Edo period. Characterized by its woodblock prints, ukiyo-e art depicted everyday life, landscapes, and the beauty of nature. The style of ukiyo-e has notably inspired many Western artists in the 19th century, including the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. The use of flat planes of color and emphasis on silhouettes in ukiyo-e prints can be seen echoed in the works of Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet.

Ukiyo-e’s graphic and narrative qualities continue to resonate within various forms of contemporary Japanese visual culture, such as manga and anime. These mediums employ techniques akin to those found in ukiyo-e, like distinct line work and dramatic composition.

Today, traditional ukiyo-e woodblock printing techniques are preserved by artisans in Japan. There is a dedicated effort to maintain the historical methods, materials, and aesthetic values, ensuring that the legacy of ukiyo-e remains intact and accessible.

Globally, museums and private collectors cherish ukiyo-e pieces for their historical and aesthetic significance, displaying works that provide insight into Japanese life during the Edo era, as well as demonstrating the art form’s evolution. By understanding its continued relevance and adaptation, the legacy of ukiyo-e Japanese prints is emblematic of the enduring power of art to influence beyond its original context and era.

Ukiyo-e stands as a testament to the rich artistic heritage of Japan, embodying the spirit of its people and the dynamic cultural milieu of the Edo period. Its enduring popularity and influence extend far beyond its historical context, resonating with audiences worldwide and inspiring countless artists across generations. Through its intricate designs, vibrant colors, and evocative themes, ukiyo-e continues to captivate and enthrall, inviting viewers to explore the multifaceted layers of Japanese history, society, and aesthetics. As a cherished art form, ukiyo-e remains a cherished cultural treasure, preserving the essence of the “floating world” for generations to come.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Is Ukiyo-e Correctly Pronounced?

Ukiyo-e is pronounced as oo-kee-yo-eh. The term comprises four syllables, and care should be taken to pronounce each one distinctly.

In What Ways Did the Ukiyo-e Style Influence Modern Art?

The ukiyo-e style significantly influenced Western artists, particularly the Impressionists, with its bold lines, unique perspective, and flat areas of color. These elements inspired artists such as Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet in their use of color and composition.

What Historical Period Did Ukiyo-e Art Flourish?

Ukiyo-e art flourished during Japan’s Edo period, which spanned from 1603 to 1868. This period saw the rise of a wealthy merchant class with the means and leisure time to support the arts, including the distinctive woodblock prints of ukiyo-e.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Ukiyo-e – A Glimpse into Japan’s Pictorial History.” Art in Context. March 11, 2024. URL: https://artincontext.org/ukiyo-e/

Meyer, I. (2024, 11 March). Ukiyo-e – A Glimpse into Japan’s Pictorial History. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/ukiyo-e/

Meyer, Isabella. “Ukiyo-e – A Glimpse into Japan’s Pictorial History.” Art in Context, March 11, 2024. https://artincontext.org/ukiyo-e/.