Artemisia Gentileschi – Baroque Painter and Boundary Breaker

Artemisia Gentileschi is often described as the female hero of Italian Baroque art. Through many of her works, Gentileschi’s work made a statement that women’s oppression is a legitimate subject of art – a theme never before explored so explicitly from a female perspective. Gentileschi was also one of the first women to earn the professional acknowledgement required to make a living from her art, and as such, she was celebrated internationally. In this article, we take a closer look at Artemisia Gentileschi’s biography.

Table of Contents

Artist in Context: Who Was Artemisia Gentileschi?

Artemisia Gentileschi was one of the greatest 17th-century Italian painters. She was a professional painter by the age of 15. Initially, she painted in a Caravaggio style but later developed into a Baroque painter. Below, we explore Artemisia Gentileschi’s biography in more depth.

| Date of Birth | 8 July 1593 |

| Date of Death | 1654 |

| Country of Birth | Rome, Italy |

| Art Movements | Baroque Art |

| Mediums Used | Oil Painting |

Childhood and Education

Artemisia Gentileschi was born in Rome in 1593 as the only daughter and eldest of five children. Her mother, Prudentia Montone, passed away when the young artist was only 12 years old. Gentileschi’s father Orazio was an artist who taught her how to paint as a young girl.

Her father also introduced her to other prominent artists of the time, including Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, whose chiaroscuro style greatly influenced her.

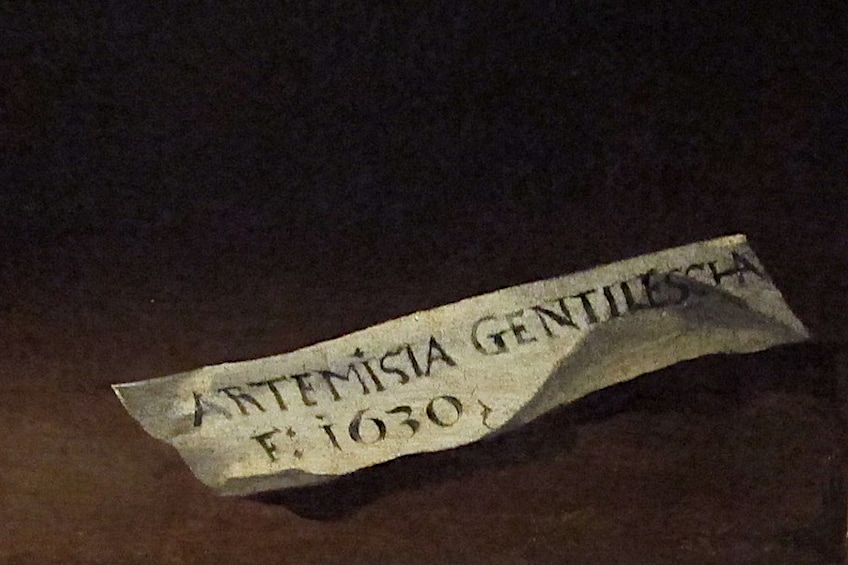

Although her father trained her as a painter, Gentileschi didn’t receive any other schooling and only learned how to read and write as an adult. Gentileschi signed and dated her first work, Susanna and the Elders, in 1610 at the young age of 17.

Her father enlisted his acquaintance and collaborator, Agostino Tassi, to train her perspective painting. A year later, 18-year-old Gentileschi was raped by Tassi. Gentileschi’s father had Tassi arrested when he found out.

The trial ensued in 1612, details of which were meticulously recorded and survived in archives over the centuries.

Artemisia Gentileschi was sentenced to torture to prove her innocence and her reputation was ruined during the trial. Tassi was found guilty, but while his sentence meant his banishment from Rome, it was never enforced.

Mature Period

Shortly after the trial, Gentileschi’s father arranged for her to be married to Pierantonio di Vincenzo Stiattesi, a little-known Florentine painter. After the wedding, she moved to Florence, where she continued her artistic practice, while also mothering five children. In 1616, Gentileschi became the first female artist to receive membership to the Florence Academy of the Arts of Drawing. This membership allowed her to sign contracts and purchase art supplies without needing consent from her husband.

One of her biggest supporters during this time was Cosimo II de’Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany.

In 1618, after the birth of their first daughter, Gentileschi started a controversial affair with Francesco Maria di Niccolò Maringhi, a nobleman from Florence. Part of the reason why the affair was so controversial, was that Gentileschi’s husband was aware of the affair, and even communicated to Maringhi through his wife’s love letters.

The letters, which were discovered in 2011 by Francesco Solinas, an academic historian, apparently implied that Maringhi kept the married couple out of financial ruin.

Stiattesi had a reputation for mishandling money, and the couple’s financial problems, along with rumors of the affair between Gentileschi and Maringhi, prompted the couple to part ways in 1621. Gentileschi returned to Rome without her husband, and she would continue to work in Rome for ten years.

Late Period

Gentileschi was not as successful in Rome as she hoped to be and at the end of the century, traveled to Venice in search of new commissions. In 1930, she decided to move to Naples with her daughter, continuing her nomadic lifestyle without her husband. Here she established a successful artist studio that ran till her death in 1654. During her time in Naples, she worked alongside many famous artists, including Massimo Stanzione.

Although she stayed in Naples until the end of her life, records show that she traveled to London for a few years. Part of the reason for this was that her father, who was a court painter of Charles I, was commissioned to paint a fresco for the Greenwich residence of Queen Henrietta Maria, the wife of Charles I. It is believed that Gentileschi went to England to assist her father, who was getting very old, with the fresco. Her father passed away in 1639, at 75 years old.

Records indicate that Gentileschi remained in England after the death of her father and that she likely remained until 1642 when the civil war broke out..

During this period in London, Gentileschi painted some of her most famous works, including her Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (1638).

Inspirational Artemisia Gentileschi Quotes

Artemisia Gentileschi’s spirit comes through in the archives of what she wrote in her lifetime. Through looking at some of her quotes, we get a clearer image of her personality and the challenges she had to face as a female artist in a male-dominated world. Below are five of our favorite Artemisia Gentileschi quotes:

- “As long as I live I will have control over my being.”

- “I have made a solemn vow never to send my drawings because people have cheated me. In particular, just today I found… that, having done a drawing of souls in Purgatory for the Bishop of St. Gata, he, in order to spend less, commissioned another painter to do the painting using my work. If I were a man, I can’t imagine it would have turned out this way.”

- “My illustrious lordship, I’ll show you what a woman can do.”

- “They [clients] come to a woman with this kind of talent, that is, to vary the subjects in my painting; never has anyone found in my pictures any repetition of invention, not even of one hand.”

- “You will find the spirit of Caesar in the soul of a woman.”

Five Interesting Artemisia Gentileschi Facts

Despite being overshadowed at the time by many of her male contemporaries, Artemisia Gentileschi is today considered to be one of the most esteemed Baroque painters.

Her work depicted popular tales and tropes from a female perspective, something that her male contemporaries could not achieve.

The following five Artemisia Gentileschi facts highlight how her passionate feminist spirit resulted in her becoming one of Italy’s most accomplished artists, against all odds.

- Some of the most famous Artemisia Gentileschi paintings were created before the artist turned 25. Some of these include Susanna and the Elders, which she painted at age 17, and Madonna and Child, painted at age 20.

- Gentileschi made history when she was the first female artist in Florence to gain membership to the Academy of Arts. This is a remarkable achievement since female painters were not generally accepted into the art world at this time.

- She was friends with Galileo Galilei. Gentileschi met Galilei, the influential astronomer, engineer, and physicist, at the Academy in Florence and they corresponded by letter to keep in touch.

- George Eliot wrote a novel inspired by Gentileschi’s life. Eliot’s books were similar in style to Gentileschi’s paintings as they passionately describe real-life situations, and her novel Romola, which is set in Florence, mimics life events from Gentileschi’s life.

- Judy Chicago’s famous installation, The Dinner Party (1974-1979), includes a seat at the table for Gentileschi. Chicago’s Contemporary Feminist artwork is an installation that comprises 39 elaborate place settings on a triangular table that honor 39 historical and mythical women that paved the way for women’s liberation.

Important Artemisia Gentileschi Paintings

Artemisia Gentileschi had important patrons throughout her career and to this day, she is the symbol of an influential Feminist icon. Many of her works feature the stories of women in myths and biblical tales. Her Feminist approach to life radiates through these paintings. Below, we discuss four works that best illustrate how she empowered women through her art.

Susanna and the Elders (1610)

| Artwork Title | Susanna and the Elders |

| Date | 1610 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Size (cm) | 170 x 119 |

| Collection | Schloss Weißenstein collection, Pommersfelden, Germany |

There have been multiple depictions in the 16th and 17th-century art history of the tale of Susanna and the elders, from the book of Daniel. The tale describes how Sunna, a virtuous and beautiful young woman, is bathing in her garden, while two older men secretly watch her. The men suddenly approach her, demanding that she submit to them. If she does not, they will ensure that her reputation is ruined by proclaiming that they observed another man in the gardens.

The depictions that preceded Gentileschi’s version typically depicted Susanna as being somewhat seductive, and the only traces of violence are hidden within the title or suggested in a gentle tug of her dress. Gentileschi’s version is very different.

In her version, two men forcefully encroach from behind a marble balustrade. Susanna is not depicted as seductive, but rather one hand covers her face while the other is reached out in self-defense. Artemisia Gentileschi’s painting of Susanna is regarded as the first painting to show sexual violence from the viewpoint of the woman, the victim. Gentileschi painted this work when she was only 17 years old, and shows incredible talent for such a young artist.

In a version Artemisia painted thirty-nine years later, a far more confident Susanna actually pushes one of the old men away from her.

Judith Slaying Holofernes (1620)

| Artwork Title | Judith Slaying Holofernes |

| Date | 1620 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Size (m) | 158 x 125 |

| Collection | The Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy |

Judith Slaying Holofernes is yet another biblical scene painted by Gentileschi. In fact, Gentileschi returned to this scene several times during her career. Traditionally, the tale of Judith slaying Holofernes is depicted by artists in a rather idealistic manner, where Judith’s beauty and courage are the central focus of the work. In 1598, Caravaggio, whom Gentileschi admired very much, painted the same event with great realism, focusing more on the act of the beheading.

In Gentileschi’s version she takes Caravaggio’s realistic approach a step further by also attempting to capture the psychological headspace of Judith, as well as portraying the intensive physical demands of beheading someone.

The gestures of both Judith and Holofernes show the force of the struggle between the subjects, the passionate scene enhanced by a dramatic use of color and intense chiaroscuro.

This is one of several paintings in which Gentileschi both highlights the power of women and shows women taking revenge on men. From her own life experiences, we can see how Gentileschi could use her art to give voice to her frustrations and anger toward the men that wronged her. In fact, some critics believe that Judith is in some way a self-portrait of the artist. Not only does Gentileschi depict Judith as powerful mentally and physically strong, but she also empowers Judith’s servant.

In previous renderings of the tale, Judith’s female servant is depicted as being passive, standing in the background and waiting to receive the severed head of Holofernes. In Gentileschi’s version, however, the servant is actively assisting Judith in the beheading.

In this bold change of traditional depictions, Gentileschi seems to propose that women are stronger when standing up together against those who oppress them. In a following image, Judith and her maid are depicted as co-conspirators, concealing the evidence of their crime.

Lucretia (1620 – 1621)

| Artwork Title | Lucretia |

| Date | 1620 – 1621 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Size (cm) | 100 x 77 |

| Collection | Gerolamo Etro, Milan, Italy |

This painting depicts Lucretia, a heroine in Roman mythology, who was the wife of a Roman army commander, Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus. The painting depicts the moment when Lucretia is about to commit suicide because she was sexually assaulted by one of her husband’s soldiers, Sextus Tarquinius, who was also the son of the Roman King. According to legend, Sextus Tarquinius raped Lucretia at knifepoint, blackmailing her by saying that he would kill both her and her handmaid if she did not submit to him. By her act of suicide, Lucretia symbolizes one woman’s defiance of male power over women’s bodies.

The myth claims that the Roman people were so outraged by Lucretia’s rape and death that they decided to overthrow the monarchy and thus founded the Roman Republic.

In Gentileschi’s painting, she paints Lucretia in dramatic chiaroscuro, the light focusing solely on Lucretia’s expressions of agony and decisive body language. Lucrecia is painted wearing only disheveled white undergarments, without any jewelry, trappings, or symbols of her wealth, highlighting that the rape had occurred only moments ago.

Gentileschi accentuates the femininity of Lucretia as she cups her breast in preparation for the dagger that would soon enter her body.

The red details of the curtains and cloth on her lap are an indication of the blood that is soon to flow. What makes Gentileschi’s painting of Lucretia so powerful is that she shows the woman taking ownership of her life and deciding for herself, whereas previous paintings of Lucretia (painted by male artists) decided to either focus on her rape or her death. Once again, when Gentileschi revisits the theme later in life, the heroine is even bolder and more decisive in her gestures and her demeanor.

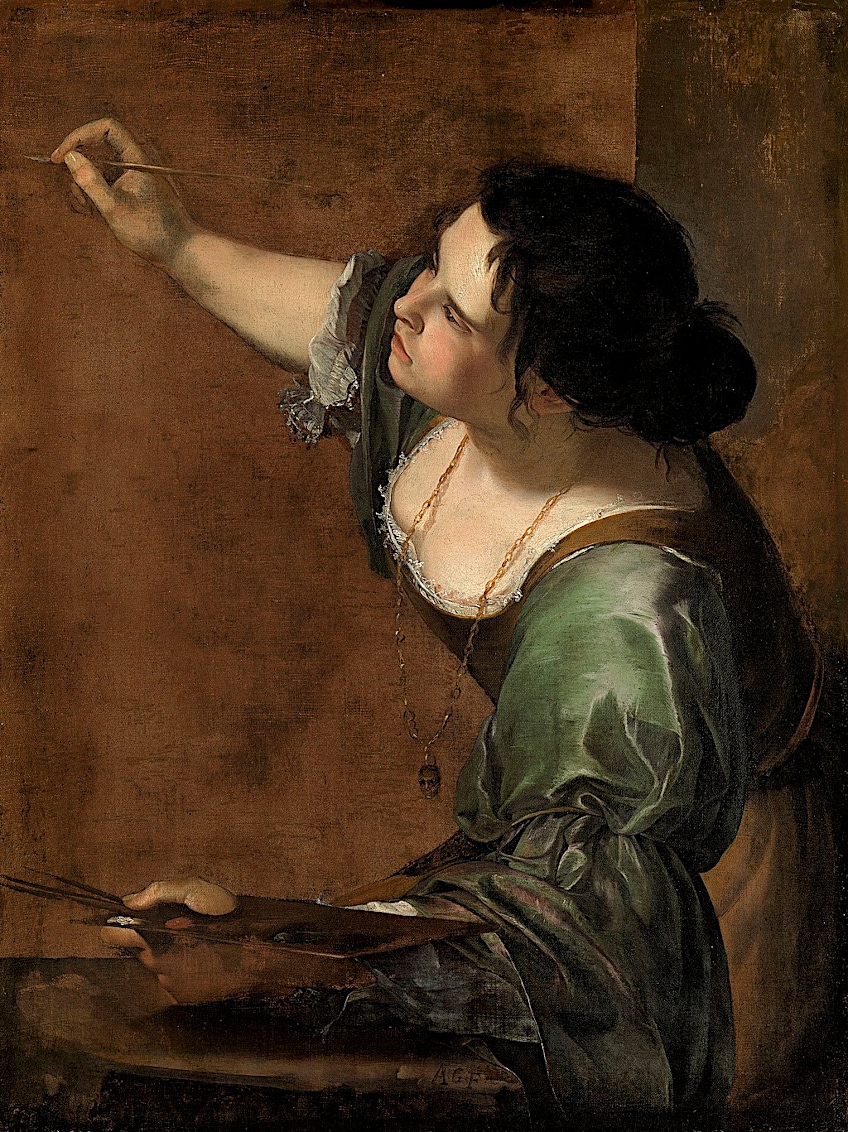

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (1638 – 1639)

| Artwork Title | Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting |

| Date | 1638 – 1639 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Size (cm) | 93 x 73 |

| Collection | Royal Collection, London, United Kingdom |

This intriguing painting is the only known artwork that Gentileschi made during her stay in London while assisting her father in his commissions. The painting is a rather idealistic depiction of herself, as Gentileschi would have been much older at the time than the version of herself that she depicted in this painting. It is also believed, like with many of her other paintings, that Gentileschi created this self-portrait by placing mirrors around her as she worked, allowing for unique perspectives. In this confident self-portrait, Gentileschi chooses to paint herself in action, painting. In the work, she also showcases her mastery as a painter, by using techniques of foreshortening and how perspective implies motion.

This painting is significant, not only because of Gentileschi’s skill as a master painter, but because it is inspired by the iconography described by Cesare Ripa.

In his book, Iconologia, Ripa describes the best ways that artists and illustrators can depict virtues and other abstract ideals visually within human figures. According to Ripa, the art of painting should be depicted as “a beautiful woman, with full black hair, disheveled, and twisted in various ways, with arched eyebrows that show imaginative thought, the mouth covered with a cloth tied behind her ears, with a chain of gold at her throat from which hangs a mask and has written in front ‘imitation’…she holds in her hand a brush, and in the other the palate, with clothes of evanescently colored drapery…”.

Gentileschi’s painting almost perfectly matches Ripa’s description, apart from her mouth being covered with a cloth.

In this painting, Gentileschi thus represents herself as the concept of art itself. The act of making this painting, together with the removal of the cloth of the mouth, speaks volumes about Gentileschi’s insistence on her own voice being heard, as well as that of all women.

Book Recommendations

Writings about Artemisia Gentileschi’s life are becoming more readily available since interest in this revolutionary artist has been renewed.

Over the past few decades, more and more works are discovered to be made by Gentileschi, works which were often wrongly attributed to be made by her male contemporaries instead.

As new information emerges on Gentileschi’s life and work, we get a fuller picture of the artist. We recommend the books below if you are interested in acquiring a deeper understanding of Artemisia Gentileschi’s biography.

Artemisia Gentileschi (1991) by Mary D. Garrard

Mary D. Garrard presents with this book, a full-length study of the life and work of Gentileschi, whom she regards as the most important female artist before Modernism. Garrard is well-equipped to write and compile this book, which she takes to the task with keen observation and intelligent questions. Garrard offers new insights into Gentileschi’s original and unique treatment of the female figure in myth and legend, and with scholarly insight, she brings the work of Gentileschi to a much broader audience.

- Well written, thoroughly researched, and highly insightful

- Provides a lot of contextual information, but limited color plates

- Not ideal for beginners or readers unfamiliar with art history

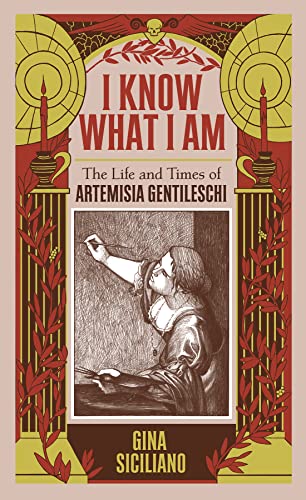

I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi (2019) by Gina Siciliano

This book is a stunning graphic novel about the life of Artemisia Gentileschi, a pioneering female painter. The book imaginatively tells the story of Gentileschi, whom they argue is Italy’s greatest female painter. The book is a complex feminist portrait, painting the story of Gentileschi as a sexual assault survivor, a single mother, and a dedicated career-driven artist.

- Unusual but engaging format for an art historical book

- Combines visual and literary storytelling with historical research

- Extremely detailed portrait of the artist and her period

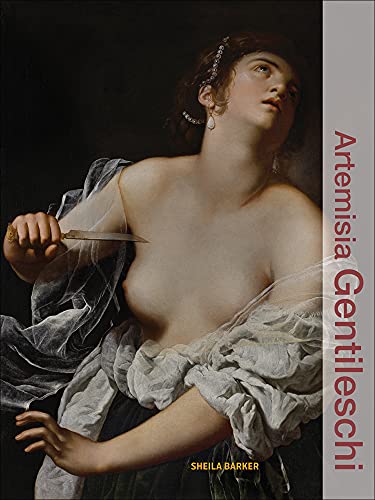

Artemisia Gentileschi (Illuminating Women Artists) (2022) by Sheila Barker

This book is the newly released second volume of the Illuminating Women Artist series, focusing specifically on the life and work of Artemisia Gentileschi. Sheila Barker presents in this book all the newest discoveries in the artist’s life and work. The book, which is filled with stunning illustrations and photos, offers a deep analysis of some of Gentileschi’s most loved works, mapping the artist’s development techniques and evolution of goals throughout her life.

- Well-written and lavishly illustrated with full color plates

- Provides deep insight into the artist's personal and social contexts

- Includes detailed discussions and analyses of individual artworks

Despite the challenges of working as a painter in a male-dominated world, Artemisia Gentileschi recognized that being a woman was a strength she could leverage in her work. Gentileschi realized that she could imbue her work with a uniquely female perspective, something that was impossible for her male contemporaries. This perspective was not only informed by her experience of overcoming victimhood as a teenager but also by the experience she gained from motherhood, and her erotic passion, her professional ambitions as a woman. Gentileschi recognized that she had a rare authority in offering women’s perspectives in well-known myths and tales, and with her brushstrokes, she chose to empower and give voice to those subjects who were previously silent.

Take a look at our Artemisia Gentileschi paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Was Artemisia Gentileschi a Feminist?

It is contextually irresponsible and therefore academically inappropriate to ascribe adherence or belief in modern ideologies to historical figures. However, we can say that women like Artemisia Gentileschi who were able to escape some of the limitations placed on women during their time-periods served as inspiration for the Feminist movement. Artemisia Gentileschi’s life was extremely unusual for a 17th Century woman. Long before the Feminist movement was conceptualized, Gentileschi was able to enjoy a degree of personal, professional, and intellectual freedom that can now be aligned with Feminist ideology. Whenever referencing the female body or sexuality in her paintings, she made sure to depict these women as strong and defiant, and as having ownership over their own bodies.

What Happened to Artemisia Gentileschi’s Work After Her Passing?

Although Artemisia Gentileschi achieved international acclaim during her lifetime, her reputation faded after her passing. This is partly because the Baroque style of painting quickly went out of style, to be replaced by Classicism. Only in the mid-20th century, interest in Gentileschi’s work renewed. An important exhibition in 2001 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York explored Gentileschi’s work alongside her father’s historical paintings. Before this exhibition, Artemisia Gentileschi’s name was often used in academic books as a footnote to her father’s name. After this exhibition, her name went from a footnote to being the name of one of the most important Italian Baroque artists in history.

Chrisél Attewell (b. 1994) is a multidisciplinary artist from South Africa. Her work is research-driven and experimental. Inspired by current socio-ecological concerns, Attewell’s work explores the nuances in people’s connection to the Earth, to other species, and to each other. She works with various mediums, including installation, sculpture, photography, and painting, and prefers natural materials, such as hemp canvas, oil paint, glass, clay, and stone.

She received her BAFA (Fine Arts, Cum Laude) from the University of Pretoria in 2016 and is currently pursuing her MA in Visual Arts at the University of Johannesburg. Her work has been represented locally and internationally in numerous exhibitions, residencies, and art fairs. Attewell was selected as a Sasol New Signatures finalist (2016, 2017) and a Top 100 finalist for the ABSA L’Atelier (2018). Attewell was selected as a 2018 recipient of the Young Female Residency Award, founded by Benon Lutaaya.

Her work was showcased at the 2019 and 2022 Contemporary Istanbul with Berman Contemporary and her latest solo exhibition, titled Sociogenesis: Resilience under Fire, curated by Els van Mourik, was exhibited in 2020 at Berman Contemporary in Johannesburg. Attewell also exhibited at the main section of the 2022 Investec Cape Town Art Fair.

Learn more about Chrisél Attwell and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Chrisél, Attewell, “Artemisia Gentileschi – Baroque Painter and Boundary Breaker.” Art in Context. January 15, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/artemisia-gentileschi/

Attewell, C. (2023, 15 January). Artemisia Gentileschi – Baroque Painter and Boundary Breaker. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/artemisia-gentileschi/

Attewell, Chrisél. “Artemisia Gentileschi – Baroque Painter and Boundary Breaker.” Art in Context, January 15, 2023. https://artincontext.org/artemisia-gentileschi/.