Edvard Munch – A Look at the Artist Behind Edvard Munch’s Paintings

Critics once accused Edvard Munch of making slapdash art. Nothing could be further from the truth. The isolated Munch artist cared so much about the works that he treated them like children. He literally took them out to the beach or for tea. This arguably odd relationship with his art was a result of Edvard Munch’s biography being plagued by illness, tragedy, and loss.

Table of Contents

- 1 The Dark Allure of Edvard Munch

- 2 An Edvard Munch Biography

- 3 A Lasting Legacy

- 4 Frequently Asked Questions

The Dark Allure of Edvard Munch

| Date of Birth | 12 December 1863 |

| Date of Death | 23 January 1944 |

| Place of Birth | Løten, Norway |

| Associated Art Movements | Expressionism, Post Impressionism |

| Genre/Style | Painting, Printmaking |

| Mediums Used | Tempura, oil paint, watercolor, pastel, charcoal, Etching, Aquatint, Lithography, Woodcut |

| Dominant Themes | Symbolism, mysticism, sickness, death, love, gender dynamics |

The Scream by Edvard Munch is one of the most famous images on earth. Over six decades, he created thousands of drawings, paintings, prints, sculptures, and photographs about life and death and love and birth.

Today, his work doesn’t shock us but, in his day, it provoked uproar from the public and critics alike. His perseverance is a testament to true artistic ambition.

An Edvard Munch Biography

Edvard Munch was born in the village of Løten on the 12th of December 1863. His mother Laura Catherine Bjølstad and father Christian Munch married in 1861 and moved to Christiania in 1864. He had three sisters, Sophie, Laura, Inge, and a brother Andreas. In 1868, at the age of five, Edvard’s mother died of tuberculosis, then his elder sister Sophie also died of tuberculosis in 1877. His grandfather and his younger sister Laura were diagnosed with mental illnesses.

His father, who had been a good parent until their mother Laura died, began to experience bouts of deep depression and obsessive behavior. Hence Edvard Munch’s aunt Karen remaining unmarried, devoted her life to raising her dead sister’s children.

Later in life, Edvard Munch would make a journal entry that expressed a deep resentment towards his father who in spite of being a physician, did nothing for his dying family members, except put his hands together and pray, processing the deaths as divine retribution. In 1879, Edvard Munch himself contracted tuberculosis and was bedridden for long periods of time, during which he took up drawing.

Munch’s artistic inclinations were encouraged by his aunt Karen who was herself an artist. He continued to draw and paint throughout the rest of his childhood.

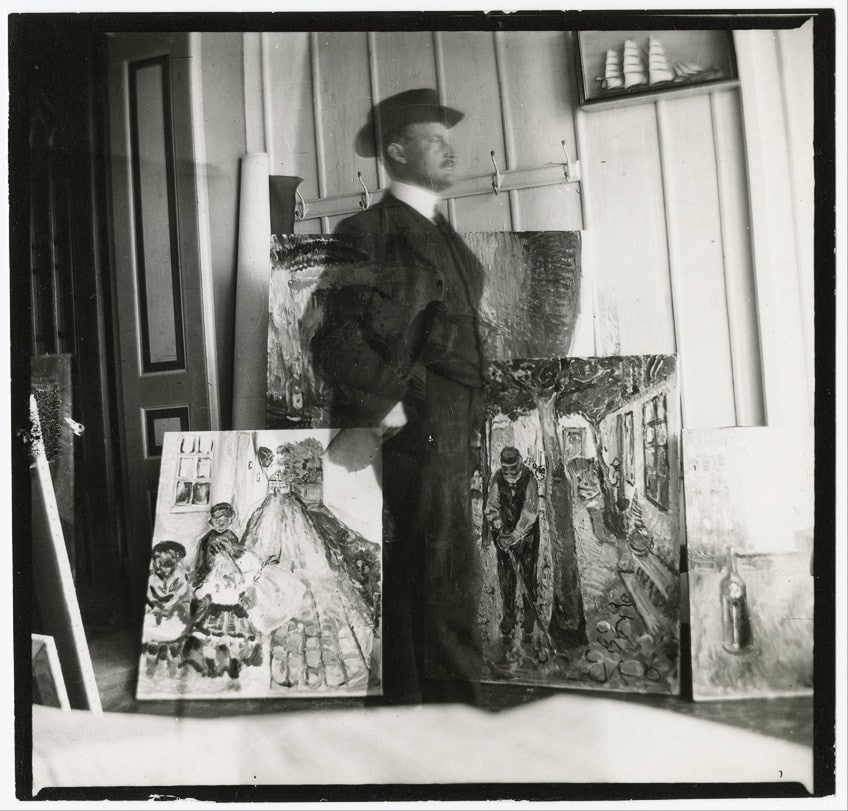

While he briefly abided by his father’s wishes and began studying engineering, he later declared “it is my decision now to become a painter.” Munch enrolled at the Royal School of Drawing in Oslo in 1881. His early work was typical of 19th-century Norwegian art, which was hitherto untouched by modernism. Norwegian painters mastered naturalistic landscapes and depictions of human subjects.

These idyllic images were part of a campaign to instill a sense of nationalism for Norway, which was seeking independence from Sweden. However, many of Norway’s older painters had trained in Europe.

Some brought these new styles back to Norway and set up informal academies. In 1882, Munch trained with the naturalist painter Christian Krohg, and in 1883 the impressionist Frits Thaulow. Both Krohg and Thaulow encouraged their students to use the impressionist method of painting outdoors so as to capture the transience of movement and light.

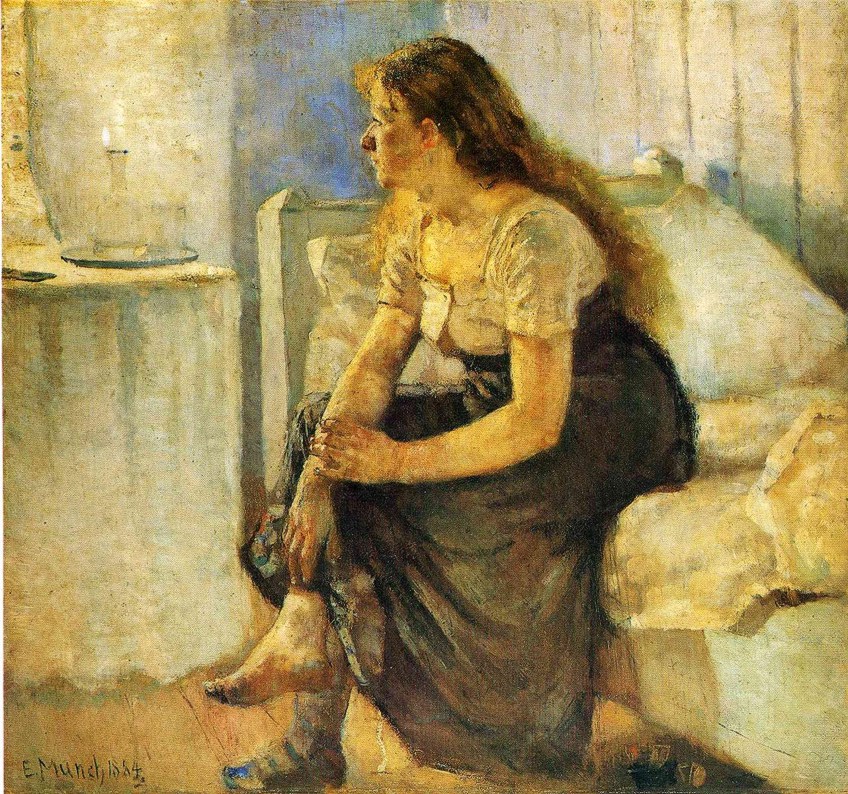

Morning (1884), Munch’s first publicly exhibited work, shows his foundations in realism. The combination of an expression of the tension in the human condition, and an engagement with light and color, makes apparent the young artist’s keen awareness of Impressionism.

In 1884, Munch began a portrait of his younger sister, which illuminated her face and hands with the left hand slightly raised.

There appears to be no movement in the remainder of her body, which is shrouded in darkness. When Edvard Munch first showed this painting, Inger in Black (1884), the conservative press in Christiania referred to it as “his almost frighteningly ugly portrait of a lady in black”, which began an almost 15-year assault on his work by critics in Norway and abroad.

The Sick Child (1885-1886)

The theme of the dying child was common in late 19th-century art. Munch drew from his own experience and memory to produce The Sick Child (1885-1886) which, measuring 119,5 cm by 118,5 cm, depicts his sister Sophie on her death bed. Her head perched on a pillow, her face turned right toward the darkness, whilst a depiction of their mother Laura who had also died when Munch was young, has her head already bowed in grief.

His sister Sophie’s death was the subject of many journal entries attempting to rekindle the details of the memory.

He wrote that he wanted to capture the memory of her pale face against the white pillow and her red hair. He did this through the use of complementary colors. The red of the hair and the greens of the dress and bedding created a coloristically compelling composition. His models were his aunt Karen and a young girl called Betsie Nelson, who had been his father’s patient.

While impressionists were focusing on light to explore the nature of things, Munch was trying to transcend the representation of exterior reality and explore something deeper about the human condition. Unlike the fast pace of the impressionist paintings, which were often done in an afternoon, Munch took over a year to complete this piece.

It became one of the first expressionist artworks in the history of western art.

Munch applied layer upon layer of paint with brush, palette knife, and even kitchen blade, then scratched things off and reapplied. The Sick Child’s deeply scored canvas constructed a complex tapestry of color and texture. Munch’s process of working and reworking excavated the surface for a moment that was engraved in his mind.

Edvard in Love

In 1885, at 21, Munch embarked on his first love affair. The 24-year-old Andrea Frederika Emily Thauwlow, nicknamed “Milly”, was a Christiania socialite married to his cousin, a city doctor who was nine years her senior. The affair between Munch and Milly started during the summer months when Munch visited the coastal hamlet of Åsgårdstrand and continued on and off for several years.

In his journals, he called her Mrs. Heiberg. Initially infatuated by her, Munch soon learned that Milly held the power in their relationship. He was tormented by her dealings with other men. Despite this, he obsessed and followed her around. One day upon greeting her in public, he was rebuked for compromising her secrecy. She ended the relationship abruptly after two years, leaving Munch shattered.

To further complicate matters, Munch’s religious upbringing filled him with feelings of guilt for the adulterous affair. His father’s pious teachings haunted him with thoughts of death and a descent into hell.

His affair with Milly shaped his relationships with women and had a profound impact on Edvard Munch’s artwork. He was afraid of being subsumed by women. In the same token, he suffered a fear of abandonment. While Munch had often worked with themes of suffering, for the first time he began to depict love, attachment, and jealousy. Not just the events, but their psychology.

He began by producing various versions of The Kiss (1892). In it the kissing lovers have their featureless faces dissolved together, in the corner of a dark room. The fusing of the two subjects communicated something beyond the physical reality of such an embrace. Munch’s friend, August Strindberg, described Munch’s The Kiss as: “a fusion of two beings the smaller of which, shaped like a calf, seems on the point of devouring the larger as is the habit of vermin, microbes, vampires and women”.

The Frieze of Life (1893 – 1894)

Ever trailed by his demons and fraught dealings with members of the opposite sex, he tore open old wounds and used them as fuel for Edvard Munch’s artwork. Munch’s impressive body of paintings, known as The Frieze of Life, is an ambitious project that came to dominate his later years.

Exploring Munch’s ideas about life and death and love and birth, it has been exhibited in various forms and locations.

What seems at a glance to be about the strength of women is hardly portrayed in a positive light. The Munch artist became fixated on vengeful women; women agonizing or provoking. On the dark and diabolic power that women supposedly exercise over men. Mostly, he cast men as victims, although his works would sometimes present the man as the predator.

The Frieze of Life: The Seed of Love

Puberty (1894-1895) depicts an anxious young girl on the cusp of a new phase of life. The eerie shadow behind her takes on a somewhat predatory life of its own. The psychological intensity in this painting sees Munch confront a near-unprecedented subject with a degree of sympathetic rawness.

Madonna (1894-1895) shows a halo-crowned, sexually dominant, climatic female figure. Her eyes were half open and her body arched in pleasure. She is lost in her own world and makes no appeal to the viewer. The naked woman is seen from her lover’s perspective during intercourse. Munch painted sperm and embryo motifs around her as a symbol of his desire.

But “Madonna” symbolizes Munch’s subliminal issues with women rather than his adoration.

Munch painted his Madonna with what he called ‘a corpse’s smile’ revealing more menace than beauty. The model for this work was Dagny Juel-Przybyszewska with whom he had a tumultuous affair. August Strindberg, with whom Munch shared Dagny, once described her as follows:

“Tall, thin, haggard from liquor and late hours, speaking with a drawn voice, broken as if by swallowed tears, with a figure of a Madonna and a laughter that drove men insane.”

The Frieze of Life: Love’s Blossoming and Demise

Ashes (1894) explores the psychology of the breakdown of a love affair. The man seems dejected. The woman is triumphant yet morally compromised. In a lithographic version of the work, Munch inscribed: “I felt our love lying on the earth like a heap of ashes”, thereby giving the painting its name.

Female power over men is featured further in Vampire (1894), in which a woman is both consoling and consuming the male figure in her embrace. Munch insisted the female figure was only kissing the man on the nape of his neck, with her tentacle-like red hair enveloping his form.

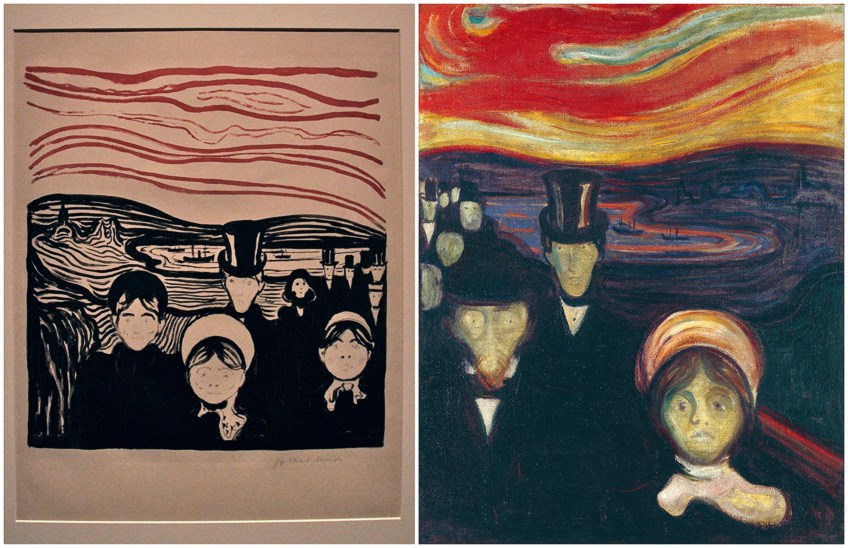

The Frieze of Life: Angst

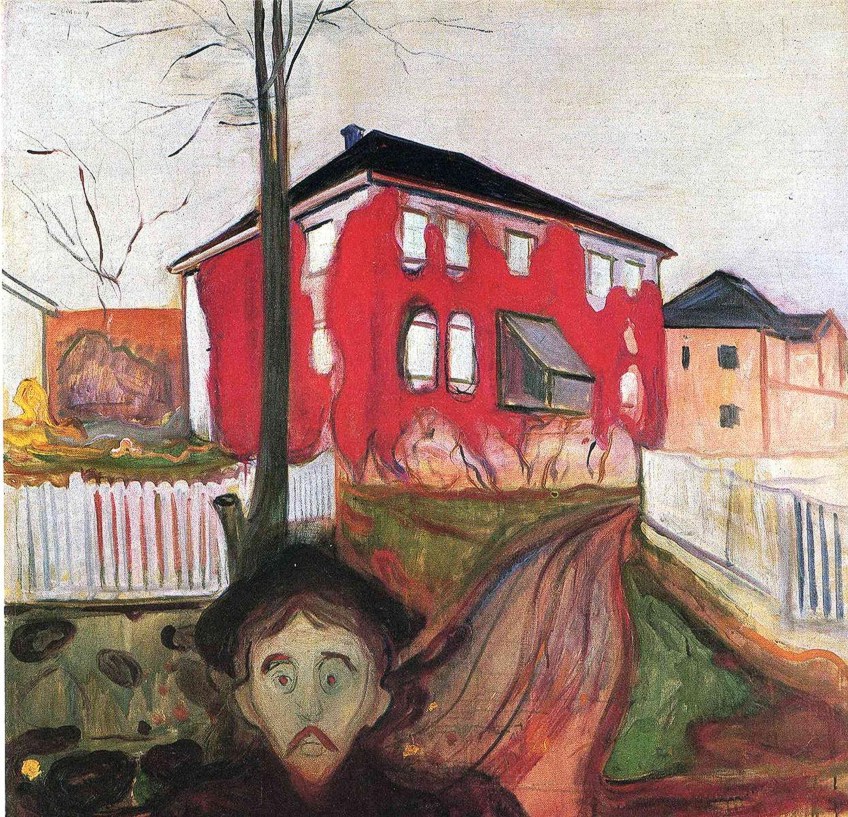

One of the better-known works by Edvard Munch, Evening on Karl Johan (1892), is confrontational, showing a modern mob marching up the main street in Christiania towards the viewer. On the right, a dark figure seems to walk against the flow, a figure that scholars have suggested is Munch, shunned by Christian society.

The ghostly faces that confront the viewer are an important precedent for “The Scream” (1893), which Munch was to paint a year later.

It is a device present in the Red Virginia Creeper (1898-1900) too, where the creepy face peers at us, demanding our attention. We’re also drawn to the house behind the figure with the bright red climbing plants, reading as blood running down the walls. We are left to wonder what horrors lie inside.

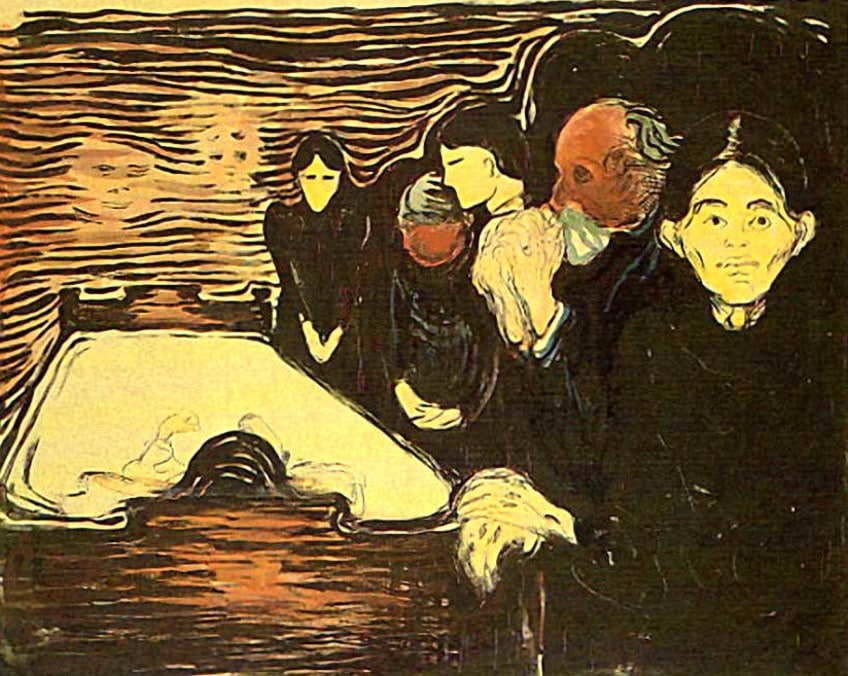

The Frieze of Life: Death

The death paintings draw on Munch’s personal tragedy and form the final part of The Frieze of Life. In Death in the Sickroom (1893) Munch puts himself in the foreground with his sisters. In the background, stands Andreas with Munch’s father and aunt around the chair in which his sister Sophie died. The siblings are shown as adults, not as the children they were at the time as if Munch is restaging the traumatic event.

The composition has a theatrical quality, with the floor sloping downwards and the figures posed as if on a stage.

In April 1895, Munch’s younger brother Andreas married 22-year-old Johanna Kink. His brother Andreas would be the only one of the five siblings to marry. Just a few months after the wedding, Andreas died of pneumonia. A year later, By the Death Bed (1896) was made.

In “By the Death Bed”, Sophie is no longer the sole focal point.

While the family is still gathered around Sophie’s deathbed, the focus moves to their hands and heads. We see his two sisters Laura and Inge, his brother Andreas, his father Christian, and his long-gone mother, her face skull-like, gripping the bedpost and standing apart from the rest of the family. Munch is absent, but the family appears linked together in grief by a big black shadow.

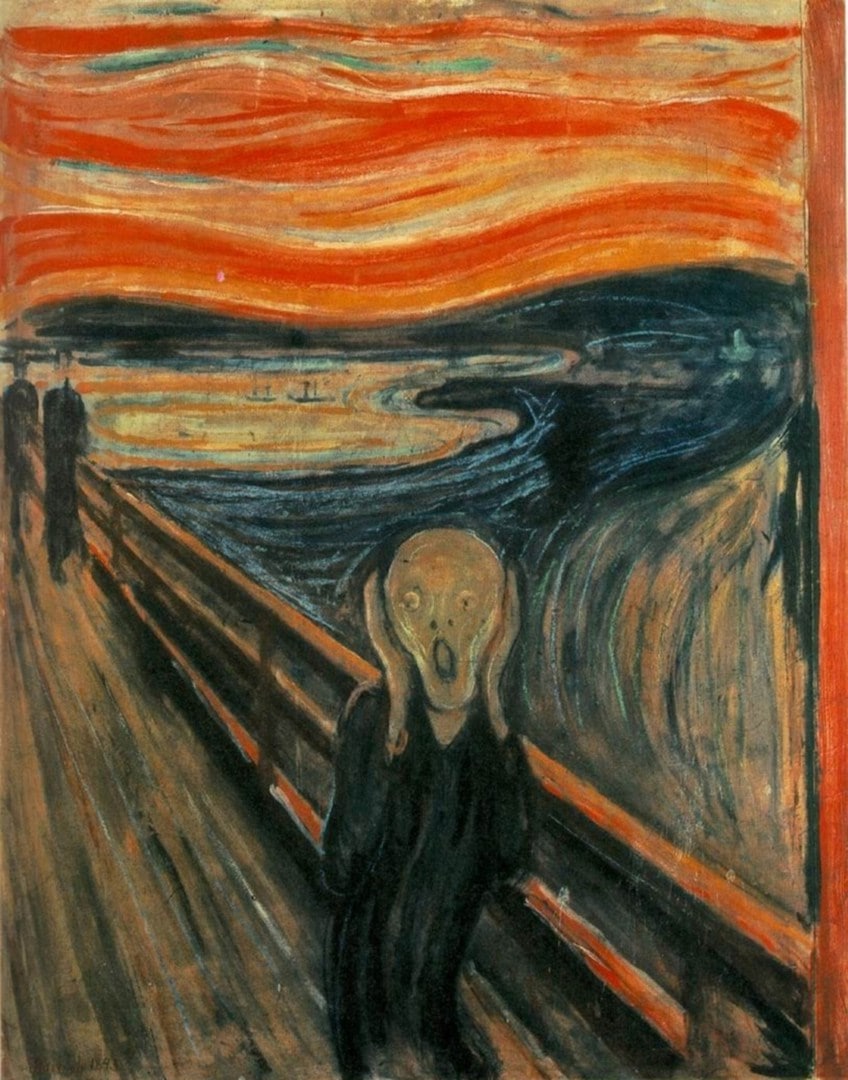

The Scream of Nature (1893)

On the 22nd of January in 1892, Edvard Munch made a journal entry that described the event that inspired his most famous painting. “I was walking along the road with two friends. As the sun went down, I felt a gust of melancholy. Suddenly the sky turned a bloody red. I stopped, leaned against the railing, scared to death as the flaming skies hung like blood and soared over the blue-black fjord and the city. My friends went on.”

He continued: “I stood there, trembling with anxiety and I felt a vast, infinite scream through nature.”

The same year he began experiencing agoraphobia, Munch created the first version of The Scream (1893). It was the final piece in the first iteration of The Frieze of Life. The painting features obscure, warped figures. The main figure occupies the foreground with two figures in the background. The figure appears mouth open and ears covered in face-melting, spine-chilling existential horror that is echoed in the background of the painting.

The lines of the composition are rendered as fluid undulated strokes of color amplified through erratic brushstrokes and pastel marks. The fiery cloudscapes of swirly red, orange and yellow complement the midnight blue water and the dark brown land. The three main lines disappear into a vanishing point in the middle of the painting with two boats in the distance, echoing the depth.

While The Scream by Edvard Munch was conceived in the very real Christiania Fjord, on Ekeberg Hill near Oslo Munch abandoned naturalism in order to manifest matters of the mind. He argued that if he had experienced the clouds as blood-red during a disturbed episode, then that is how he should depict them.

Written in pencil, within the turbulent red sky of this painting are the words: “could only have been painted by a madman”.

The Scream remains resonant for modern viewers as it reflects a common anxiety with the evolving modern world and the resultant alienation from nature. It has been parodied countless times and quoted by artists like Andy Warhol who made a version of it in 1984. Copies of The Scream have been mass-produced. Millions engage it through Halloween masks, movies, memes, and emojis. It even inspired the film poster for Home Alone.

The Dance of Life (1900)

In 1898, Munch began a catastrophic love affair with Tulla Larsen, the daughter of one of Oslo’s leading wine merchants. The nifty, obsessive Larsen pursued Munch aggressively and was intent on marrying him. He claimed the relationship began against his will and this entrapment drove him to rage and drink.

He once wrote that her romantic affection was like the “kiss of a corpse”. While he portrayed her as a desperate aggressor, he repeatedly gave in to her advances and even asked her to marry him.

At some point, he fled to Berlin and then Paris, but she followed him. After a year-long separation, he agreed to meet with her in 1902. They had an altercation and the tumultuous relationship reached a dramatic climax, which resulted in physical and psychic injury. Shots were fired. It’s not known who fired the gun, but the artist’s left hand was badly wounded. He lost the tip of his finger. Munch was maimed and embittered for years to come. He never showed his full hand in public again, always ensuring to wear a glove.

He wrote: “He had offered his hand to a female thief and she had bitten it off. Help. Help she had cried. I am drowning. Yet she had run away and it was he who had drowned.”

He memorialized the relationship in The Dance of Life (1899-1900) in which couples dance on a Nordic summer night and do not appear to notice each other. The central couple is lost in its own embrace. Their skull-like faces remind us of their inevitable demise.

The Dance of Life uses symbolism to present three phases of female sexuality. On the left, in the first stage, the young woman in white appears hopeful and innocent. In the middle, the woman in red signifies the sire, a sensuous woman dancing with a man. Her red dress was on the verge of engulfing him. To the right, an anguished older woman in black seems sorrowful. This third and final stage of female sexuality is death itself.

All three figures resemble Tulla Larsen and the man in the foreground is likely Munch himself.

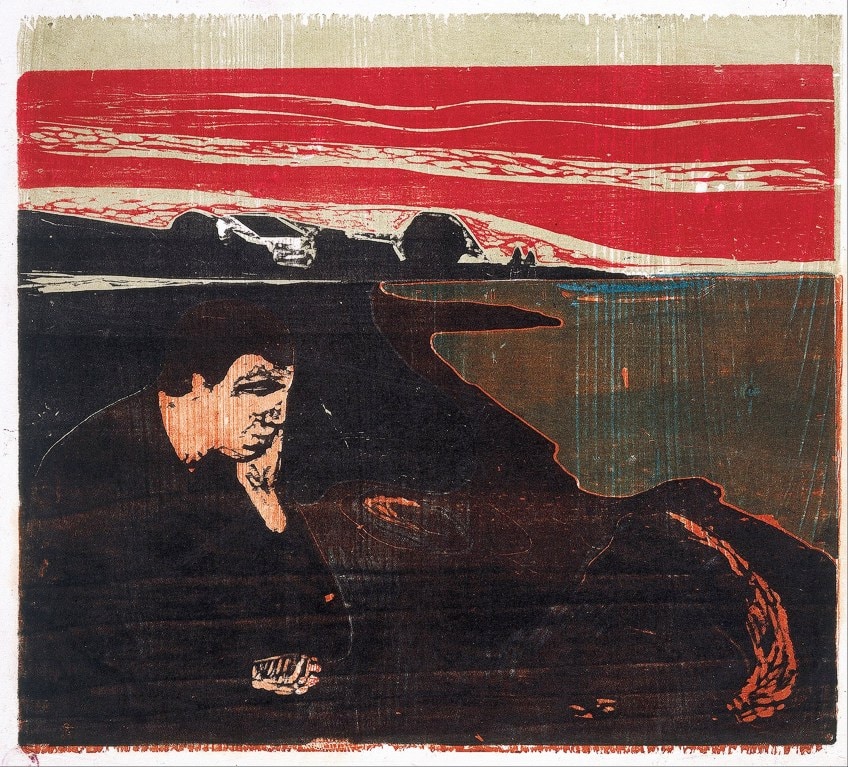

The Graphic Arts

Once he became successful, it became clear that he was paradoxically unwilling to part with his work. Because of his reluctance to sell many of his works, particularly those in The Frieze of Life, he often painted multiple versions, eventually realizing that prints were a more efficient way of spreading his art.

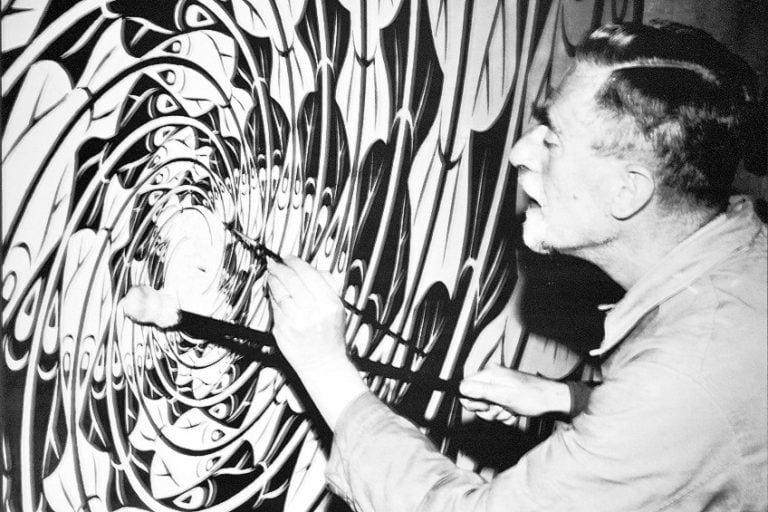

Replication became a central part of Munch’s process and his graphic output included thousands of etchings, lithographs, drypoints, and woodcuts.

Munch’s ventures into print helped him achieve financial solvency for the first time. Munch produced about 850 plates from which about 30,000 editions were made during his career. He often kept the plates from which his prints were pulled.

He stretched the emotive capacities of the medium seeing prints as a different point of view and development of something he’d captured in his paintings. He enjoyed the limitations that the print media imposed. His prints would be seen widely throughout Europe and help inspire a new movement called Expressionism, which was a by-product of the advances of the modern era.

In Germany, Munch studied the latest trends in copper engraving. Using small pieces of copper, which he carried in his pocket, Munch began his first engraving with the familiar theme of death and the maiden. An image of a naked body outstretched, pressing her body into death’s embrace.

Working on the theme of the staring and isolated faces in his work Anxiety, Munch attempted to conquer woodcut. He’d seen Paul Gaugin make use of the grain and texture of wood in the stark and simple outlines of the blocks he’d cut in Tahiti.

He even learned from the Japanese use of many-colored contours of wood.

He invented his own method of cutting pieces of wood, shaped to various contours, inking the pieces in their different colors and then fitting them back together like a jigsaw, ready for printing. He encouraged the grain of the wood to show in the print. He’d even leave the blocks outside encouraging the development of natural textures.

The Breakdown

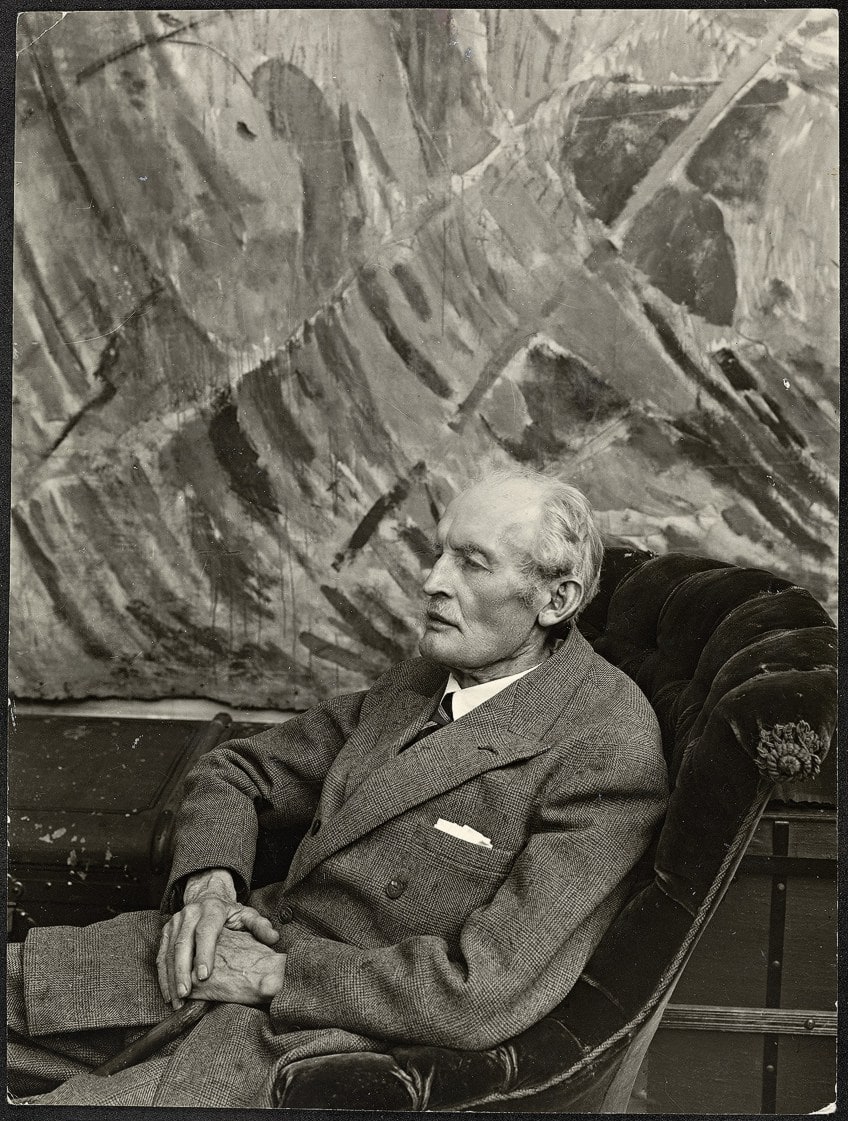

In his later years, Edvard Munch would live a life of increasing illness and isolation. His illnesses were worsened by severe drinking, smoking, anxiety, and depression. By 1908, he was hearing voices, hallucinating, and was partially paralyzed on his left side. After collapsing in Copenhagen, he finally placed himself in a psychiatric clinic in Copenhagen. He spent eight months there, receiving shock treatment and journaling as a form of therapy.

The breakdown was a definitive moment for Munch. On leaving the clinic in 1909, he retreated to the coastal town of Ekely where he reengaged with the Norwegian landscape. He practically stopped drinking and regained much of his mental clarity.

The tumultuous life he’d led was now behind him, though a new phase of isolation began. He would live alone for 35 more years.

Along with the many landscapes of this period, he developed an interest in painting working people and other ordinary scenes. The post-breakdown pieces seem to have lost something of the emotive impact of his prior paintings. It was only as his own death grew nearer that his work reclaimed some of the power it once had.

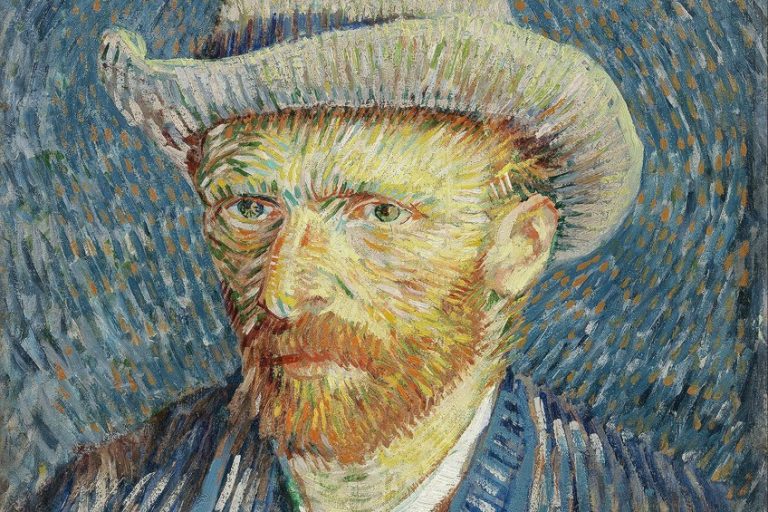

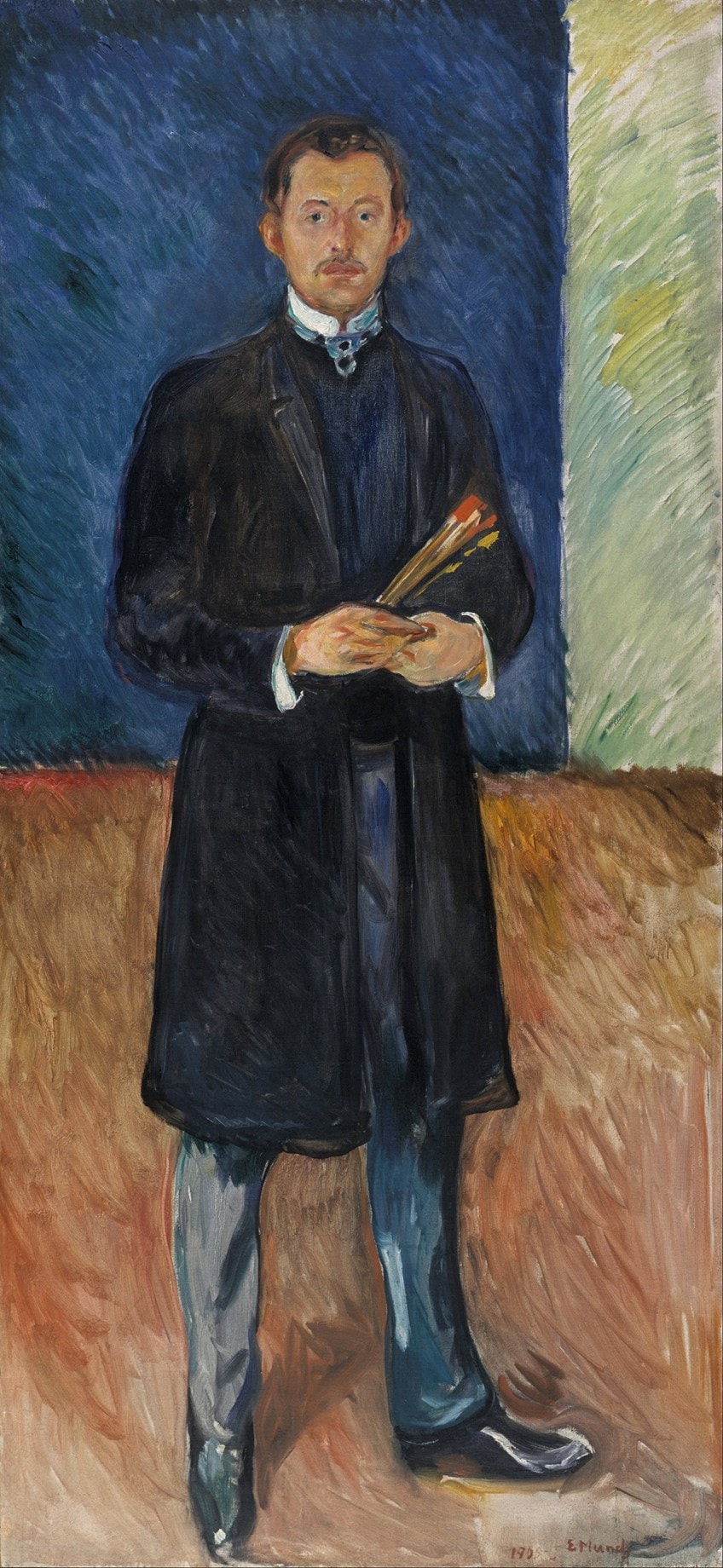

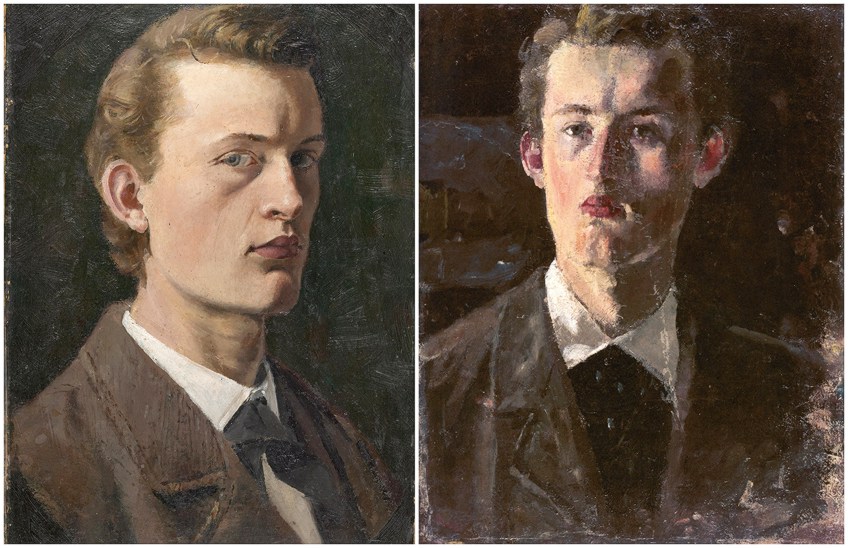

The Self-Portraits

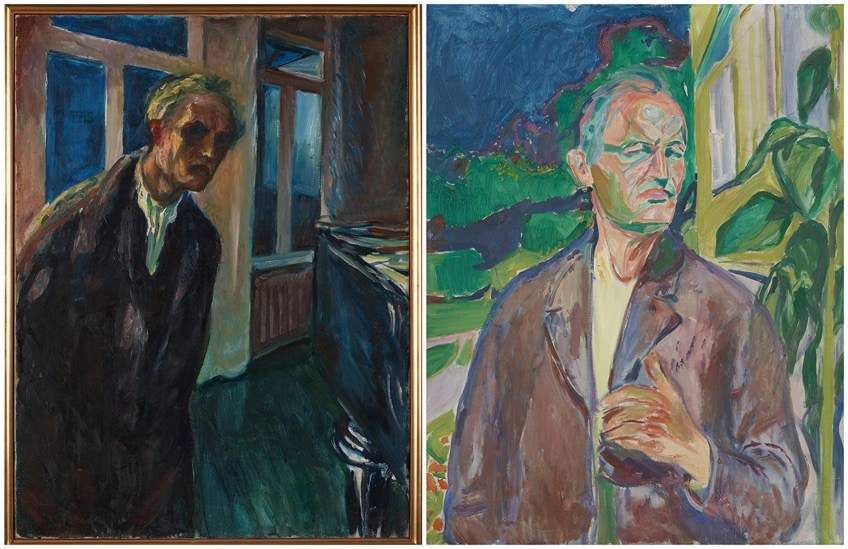

Munch’s post-breakdown work may be said to lack the emotional intensity of his earlier work, but his self-portraits improved consistently. Viewed in succession, they show his evolution from a talented young man painting in the naturalistic style to an established and expressive modern painter.

Using a reflection from a mirror, Munch painted the first of his self-portraits when he was 19-years-old.

Self-Portrait (1882) is a strongly contrasted and precisely rendered image of a confident young man with a dramatic air about him. The second Self-Portrait (1882-1883) is fluid, with softly dabbed paint and a gaze radiating the vulnerability of a still young man.

Self-Portrait (1886) is the earliest self-portrait in which Munch introduces the layered, scratchy style first seen in The Sick Child, which he’d painted just before. In Self-Portrait with a Bottle of Wine (1906), we see a melancholic Munch, sitting alone in a café, with a bottle of wine and an apparition in the background likely evoking his inner turmoil.

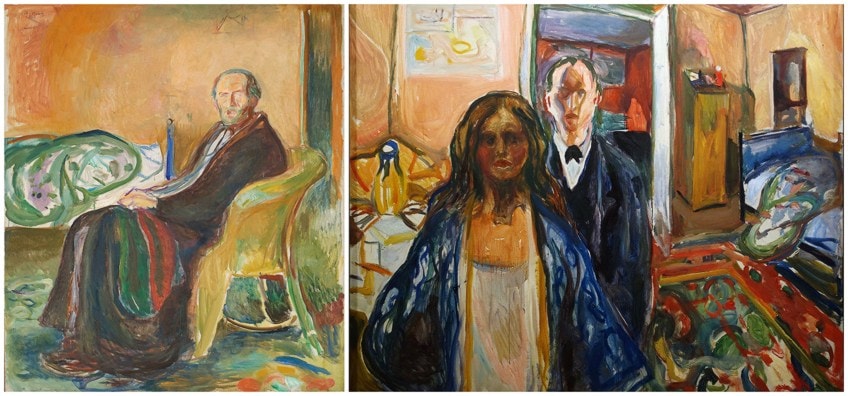

In 1919, he caught the Spanish flu but survived to paint Self Portrait with Spanish Influenza (1919). In The Artist and His Model (1919-1921), Munch depicts himself with his model. The two stand in an ambiguous relationship to one another, with a degree of tension that seems to be expressed in the brushstrokes and bold palette.

Munch retreated further into isolation at his estate in Ekely, where he rarely accepted visitors. His unflinchingly candid self-portraits would regularly feature the interior of his house. In The Night Wanderer (1923-1924), Munch presents a frank depiction of himself as a lonely, aging man shuffling through his house at night. Self-Portrait in Front of the House Wall (1926) is a coloristic experiment depicting a meek Munch.

In the months leading up to his death, he began painting Self-Portrait Between the Clock and the Bed (1940-1943). This would be his final self-portrait. There is something surprisingly ceremonial and brave in his expressive posture. A strength drawn perhaps from the vast collection of artworks that hang around him.

He paints himself as a frail and sunken old man with his sloping shoulders and hollowed-out eyes, almost apologetically bidding his final farewell to the viewer. He lingers between the two symbols of his imminent demise.

The clock stands for the passage of time and the bed has connotations of birth and death.

A Lasting Legacy

1905 was a time of great national sentiment for Norway, which had finally gained independence from Sweden. Having been largely shunned through the 1890s, Munch was finally being recognized as a key figure in Norwegian culture.

His work was bought by the National Gallery and he was commissioned to paint the Aula Murals, which was a matter of great national prestige.

He started a series of large-scale paintings, which were finished in 1916 and housed at the great hall of Oslo University, Norway. On his 70th birthday in 1933, Munch was made a Knight of the Royal Norwegian Order of St Olaf.

But in 1940, Norway was invaded by Germany and found itself under occupation. The Nazis deemed 82 of Munch’s paintings as degenerate. The works were removed from both German and Norwegian museums and auctioned off. One day a German ammunition dump exploded in Oslo harbor. The force of the blast reached as far as Ekely, causing Munch to suffer a bout of pneumonia from which he never recovered.

He died on January 23rd, 1944 at the age of 80. With him were his housekeeper and his children – the art. There were more than 20,000 artworks on his property. These included 1150 paintings, 17,800 prints, 4500 watercolors and drawings, 13 sculptures, and numerous writings and notes. His will stipulated that his entire estate be bequeathed to the city of Oslo. The collection would become what we now know as the Edvard Munch Museum in Oslo.

Take a look at our Edvard Munch paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Expressionism?

Expressionism emerged around 1905. Like post-Impressionism and symbolism, Expressionism attempted to encapsulate the feeling of things, rather than the look.

How Many Versions of The Scream did Edvard Munch Make?

The original painting of The Scream is one of four versions made. There are two pastels and two paintings on cardboard. Aside from these four paintings, Munch also made a series of prints of which there are dozens.

How Much Is The Scream?

The fourth version belongs to a private collection, having been bought at a Sotheby’s auction for $119,922,600. This is the highest amount ever paid for a painting at auction.

How Was The Scream Made?

The original Scream was painted on 73,5cm-by-91 cm cardboard using a mixture of egg tempera and pastel.

Is The Scream Damaged?

The delicate materials of this artwork make it a challenge to conserve. Various versions have sustained different amounts of damage over the years. They are covered in candle wax and bird droppings as the artist believed that exposure to the elements would help the paintings become balanced. Some say the battered surfaces echo their feeling of agitation.

Was The Scream Stolen?

Yes. The original version of The Scream was stolen in 1994 but recovered three months later undamaged. The second, a pastel on cardboard made the same year, was stolen in 2004. Two years later, it would be recovered, albeit with some moisture damage.

Where is The Scream now?

The Scream can be seen at the National Gallery in Oslo, the capital of Norway.

Heidi Sincuba was the Head of Painting at Rhodes University from 2017 to 2020 and part of the first Artist Run Practice and Theory course at Konstfack in Stockholm, 2021. They completed their BFA at Artez Arnhem in the Netherlands, MFA at Goldsmiths University of London, and are currently a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Cape Town.

Heidi Sincuba’s own practice explores fugitivity through painting, drawing, text, textiles, performance, and installation. This praxis is founded on a conceptual intersection of biomythographic experimentation, existential automatism, and African ancestral knowledge systems. These methodologies of multiplicity result in a fluid and speculative aesthetic, continually manifesting and metamorphosing its material conditions.

Learn more about the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Thembeka Heidi, Sincuba, “Edvard Munch – A Look at the Artist Behind Edvard Munch’s Paintings.” Art in Context. March 3, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/edvard-munch/

Sincuba, T. (2022, 3 March). Edvard Munch – A Look at the Artist Behind Edvard Munch’s Paintings. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/edvard-munch/

Sincuba, Thembeka Heidi. “Edvard Munch – A Look at the Artist Behind Edvard Munch’s Paintings.” Art in Context, March 3, 2022. https://artincontext.org/edvard-munch/.