Diego Rivera – Discover the Life and Legacy of Diego Rivera’s Art

Diego Rivera, typically considered the most significant Mexican painter of the 20th century, was a larger-than-life character who spent considerable stretches of his career outside of Mexico, in Europe, and the United States. Diego Rivera was regarded as a crucial figure in the Muralist art movement in Mexico and one of its pioneers. Diego Rivera’s artwork was influenced by a variety of backgrounds, including European contemporary masters and the pre-Columbian history of Mexico. Diego Rivera’s paintings, created in the fresco painting style of Italy, dealt with large issues suitable to the grandeur of his preferred art form: socioeconomic inequity, the interaction between the environment, commerce, and innovation, and Mexico’s heritage and destiny.

Table of Contents

Diego Rivera’s Biography

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Date of Birth | 8 December 1886 |

| Date of Death | 24 November 1957 |

| Place of Birth | Guanajuato, Mexico |

Diego Rivera’s murals were his preferred medium, which he appreciated for their huge magnitude and public accessibility – the polar antithesis of what he saw as the elite nature of artworks in museums and galleries.

Diego Rivera is still one of Mexico’s most beloved individuals.

He is acclaimed for both his involvement in the nation’s creative rebirth and re-invigoration of the muralist artform, as well as his enormous personality, more than 50 years after his passing. But where did Diego Rivera die and why? Let’s take a look at Diego Rivera’s biography.

Childhood

Diego Rivera and his twin brother were born in Guanajuato in 1886. His twin perished when he was two years old, and the family relocated to Mexico City soon afterward. Diego’s creative potential was nurtured by his family, who enrolled him in the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts when he was about 12 years of age.

Under the direction of a predominantly orthodox staff, he mastered conventional painting and sculpture skills.

Gerardo Murillo would become a motivating influence behind the Mexican Muralist Art Movement in the early years of the 20th century, in which Rivera participated, and was one of his classmates at the school.

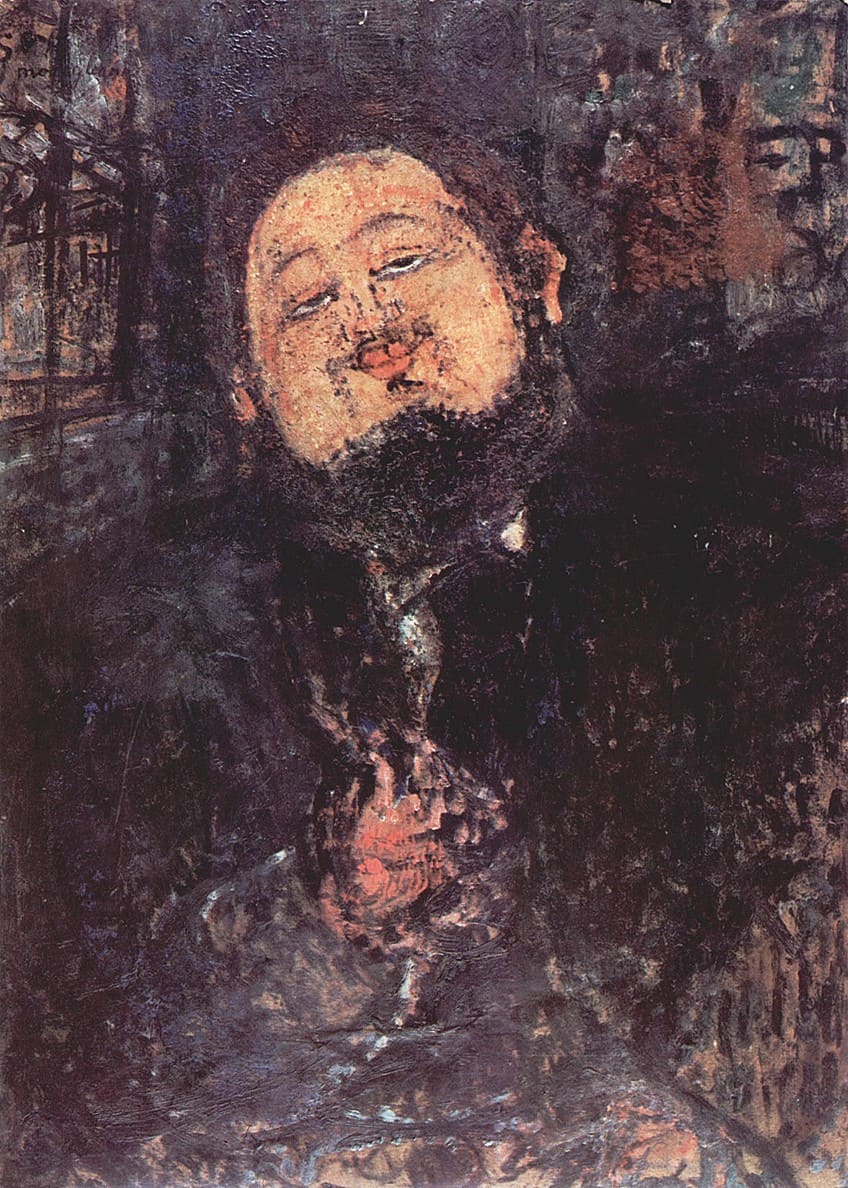

Early Training

The two students participated in an exhibit hosted by the publishers of Savia Moderna magazine in 1905 with a selection of other up-and-coming painters. Diego Rivera finished his studies in 1905 and more than 20 of Diego Rivera’s paintings were put on exhibit at the annual San Carlos Academy art display the following year. La Era (1904) is one of his paintings from this period that demonstrates Impressionism in the interplay of light and shadow, as well as the artist’s characteristic use of color. Rivera obtained government funding to study in Europe in 1907.

Rivera studied the art of Diego Velázquez, El Greco, Francisco Goya, and the Flemish painters in the Prado Museum in Spain, which served as a firm framework for his later work.

Rivera met the prominent exponents of the Madrid avant-garde, notably Ramon Valle-Inclan and Ramon Gomez de la Serna, at the workshop of Spanish realism painter Eduardo Chicharro. Rivera and Valle-Inclan flew to Belgium and Paris in 1909, where he encountered Russian artist Angelina Beloff, who would become Rivera’s companion for the next 12 years.

Rivera then held his debut exhibit at the San Carlos Academy when he returned to Mexico City in 1910. Rivera’s homecoming was timed to correspond with the start of the Mexican Revolution, which would endure until 1917. Notwithstanding the political turmoil, Rivera’s exhibition was a huge hit, and the proceeds from the purchase of his paintings allowed him to return to Europe.

Rivera returned to Paris and became a devout follower of Cubism, which he saw as a really revolutionary style of art.

Rivera’s turbulent partnerships with the other participants of the movement came to a head following a violent altercation with Pierre Reverdy the art critic. This ultimately culminated in a permanent split with the group and the end of his friendships and relationships with Braque, Picasso, Juan Gris, Gino Severini, Fernand Leger, and Jacques Lipchitz. Rivera then turned his attention to Cézanne and Neoclassical painters like Ingres, as well as a resurgence of representational art.

Rivera received another scholarship to pursue artistry in Italy, where he replicated Byzantine, Etruscan, and Renaissance artworks, with a special focus on the murals of the 14th and 15th centuries of the Italian Renaissance.

Rivera returned to Mexico in 1921 after Jose Vasconcelos was appointed as the new Minister of Education in Mexico, leaving behind his companion.

Mature Period

Rivera arrived in Mexico with a rekindled aesthetic vision, shaped by his studies of Classical and antique artwork. Under the guidance of the Ministry of Education’s program curriculum, he was given the chance to travel and study various pre-Columbian ancient sites. The first of Diego Rivera’s murals, Creation (1922), was created for the National Preparatory School and exhibits a considerable presence of Western art.

Rivera was active in local politics immediately after joining the Mexican Communist Party in 1922. He was painting frescoes in Mexico City’s National School of Agriculture at the time.

During the latter project, he became engaged with Tina Modotti, an Italian photographer who had posed for his paintings; the romance caused him to divorce Lupe Marin, his wife at the time. Rivera traveled to the Soviet Union in 1927 to attend the 10th-anniversary festivities of the October Revolution, which he found tremendously inspirational. He taught monumental art at the School of Fine Arts in Moscow for nine months. He wedded the artist Frida Kahlo, who was 21 years younger than him, and was appointed the head of the Academy of San Carlos upon his return to Mexico.

His radical educational views made him opponents among the conservative student and faculty body, and he was ousted from the Communist Party for cooperating with the state at the same time. Rivera gained backing from Dwight W. Morrow, who hired him to create a fresco in Cuernavaca’s Cortes Palace commemorating the city’s history.

Morrow, a long-time fan of Diego Rivera’s artwork, offered the artist a trip to the United States with all costs covered. Rivera stayed in the United States for four years.

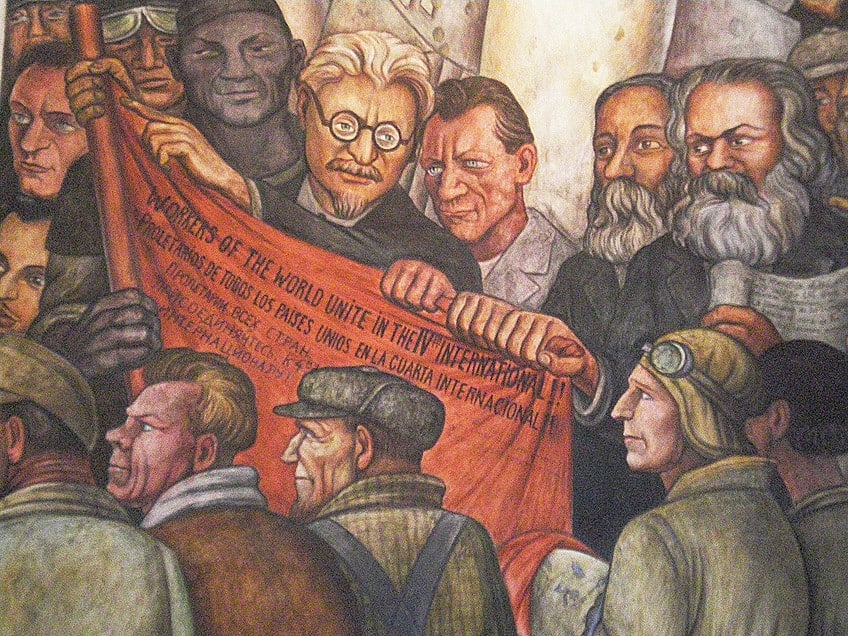

There, the prolific artist painted murals around the clock in New York, San Francisco, and Detroit, honoring the tremendous powers of labor, industry, education, and art. He was a huge hit in New York, but he also sparked a lot of debate. Rivera’s American journey came to an end in 1933, when John D. Rockefeller, Jr. ordered the removal of the mural Man at the Crossroads, which he had originally created for the lobby of Rockefeller Center, due to Rivera’s refusal to remove the picture of Lenin and what the Rockefellers considered an inflammatory depiction of David Rockefeller.

Later Years and Death

Rivera and Kahlo had a house studio in a lovely Bauhaus-style structure in Mexico City that may still be visited today when Rivera came to Mexico. Rivera painted in the National Palace on and off from 1929 to 1945, producing some of his most iconic muralist artworks there. He and Kahlo assisted Leon Trotsky and his wife in obtaining political asylum in 1937; the Trotskys resided with them in the Coyoacan area for two years.

Rivera and Kahlo separated a couple of years later, but they rejoined in San Francisco the following year, while Diego Rivera was working on the Golden Gate International Exposition.

The two had a ferociously intense and tumultuous relationship, as seen by her very intimate artworks. The pair remained together until Kahlo died in 1954. Diego Rivera continued to create murals in his later years, often on moveable panels. He also painted a lot of oil portraits, mostly of the Mexican bourgeoisie, children, and tourists from the United States. These pieces aren’t necessarily noteworthy, and they sometimes have a kitschy look that recalls Pop art.

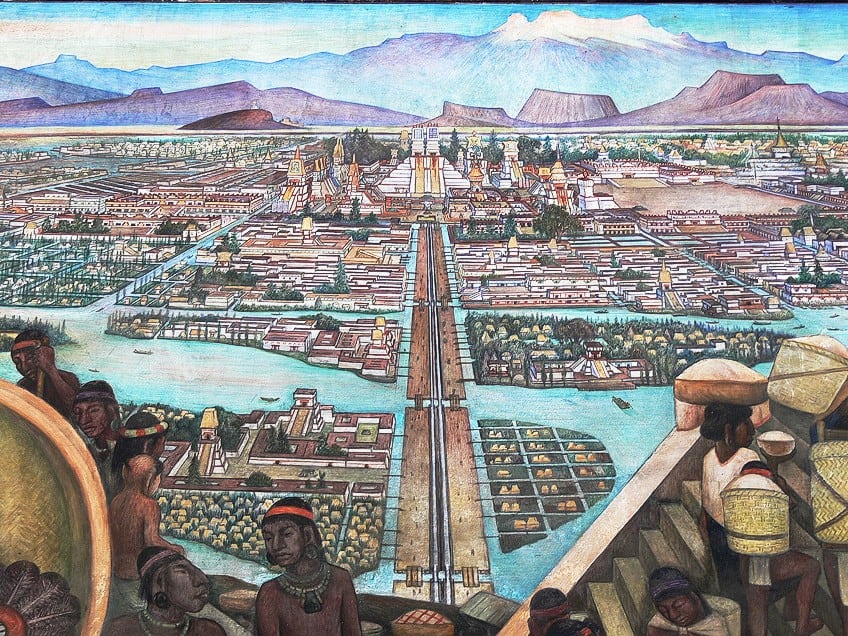

Nevertheless, they were extremely profitable throughout his lifetime, allowing the artist to add to his impressive collection of pre-Columbian artifacts. His artwork is now kept at the Anahuacalli Museum, a structure inspired by Tenochtitlan’s Great Temple and constructed by Rivera himself. Rivera remarried in 1955 to Emma Hurtado, his dealer since 1946, despite being widowed and suffering from cancer.

Rivera died in Mexico in 1957 at the age of 70, following a voyage to the Soviet Union in the hopes of treating his disease. His request that his ashes be interred beside those of Kahlo’s was denied, and he was laid at Mexico’s “Rotunda of Famous Men”.

Legacy

Rivera considered the artist as an artisan at the disposal of the people, who needed to use a visual language that was simple to understand. This notion had a significant impact on American public art, inspiring projects such as the Federal Art Project of the Works, in which artists painted images from everyday life in America on government facilities.

Rivera influenced painters as varied as Thomas Hart Benton, Ben Shahn, and Jackson Pollock with his socially and politically wide aesthetic vision, storytelling focus, and utilization of symbolism.

Diego Rivera’s Paintings

Rivera created an incredible oeuvre using the facade of academic institutions and other municipal areas throughout the United States and Mexico as his canvas, reviving curiosity in muralist art and helping to recreate the idea of public art in America by laying the groundwork for the Federal Art Program of the 1930s. The principal topics and influences on Diego Rivera’s artworks were Mexican history and culture.

Rivera, who acquired a great collection of pre-Columbian artifacts, painted panoramic depictions of Mexican history and daily life in a manner heavily influenced by pre-Columbian civilization, from its Mayan roots through the Mexican Revolution and post-Revolutionary present.

Rivera, a longtime Marxist who was a member of the Mexican Communist Party and had close relations with the Soviet Union, is a model of a socially conscious artist. Diego Rivera’s paintings depicted the Mexican farmers, American laborers, and revolutionary icons like Emiliano Zapata and Vladimir Lenin, expressing his unabashed support for left-wing political issues. His forthright, uncompromising communist ideas occasionally clashed with affluent benefactors’ preferences, causing enormous controversy both inside and beyond the art world.

View of Toledo (1912)

| Date Completed | 1912 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 112 cm x 91 cm |

| Current Location | Fundacion Amparo R. de Espinosa, Puebla |

Primarily, the material is based on a masterpiece by Greek painter El Greco of the same name. Rivera meticulously examined his work and admired the expressive style in which he worked at the time. El Greco’s View of Toledo was painted in 1599, but it remains curiously current even after all these years. Both compositions include a cityscape from a distant vantage point, and the painters chose spots on the city’s outskirts that are very similar.

El Greco’s rendition would thrill us with a chaotic sky scene, but Rivera’s version is a little quieter, with a river running around the bottom of the picture, providing a counterpoint to the sky at the top.

He also does both in a very flat blue tone, which adds to the general relaxing feeling of the work. The positivism continues in the Mexican rendition, with the rooftops and walls of each structure brightened significantly, possibly indicating the common style utilized in this region of the world. Toledo is a beautiful city with a lovely setting that is complemented by old and appealing architecture.

El Greco was born in Greece but spent much of his life in Spain, which illustrates why so many of his most famous works are currently housed in Madrid’s Prado Museum. Rivera virtually provided us with the same area the morning after, once the clouds had lifted and the sun shined through, while his rendition was immersed in the El Greco style of dramatic, dark, and somber colors.

In a symbolic gesture, the cathedral at the top rises out to the sky, looking down on the structures on the lower levels of the town. The artist sits on a bank in the foreground and informs us of this with some blooms in the foreground.

Rivera also employs a casual attitude to detail that differs from that of earlier century Realism artists, and his palette retains a link to Cezanne’s works, with pink, orange, and yellow tones.

Zapatista Landscape – The Guerrilla (1915)

| Date Completed | 1915 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 145 cm x 125 cm |

| Current Location | Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City |

In 1915, Diego Rivera completed his masterwork. He praised the artwork as an accurate portrayal of the Mexican attitude at the time. A hat, a serape, a cartridge strap, a firearm, Mexico’s highlands, and a wooden ammo box are depicted in the Zapatista artwork. The central item drifts as its planes intersect in interesting ways. The gun’s shadow is white, the reds in the picture have a particular tone, and the blues are gorgeously rendered, just like they are in Mexico.

The audience is then asked to determine the face in the piece by this “all-seeing” eye. This artwork is as secretive as a Zapatista.

There are highly crowded green clusters of woods on the left and right sides of the artwork. Over the darkness, the trees are painted in a dark viridian green. A blank piece of paper is fastened to the blue background with a nail in the lower-right corner. The trompe-l’oeil technique is used to paint the piece of paper. This bit of paper is a declaration from Mexico that stretches back thousands of years.

Rivera’s cubists produced other beautiful art pieces after he finished the Zapatista, but he never created any artwork as good as the Zapatista. He demonstrated that he was one of the most effective cubist artists with this picture.

Because of his popularity, Rivera became a major figure in theoretical disputes in wartime Paris. Rivera depicted the Zapatistas in Paris during the Mexican revolution’s brutal fight. Although the picture was not well-known at the time, it was given a new interpretation a decade later. Emiliano Zapata, a well-known guerrilla army peasant, and his supporters are the subject of the artwork’s title. Given that the title was added later, it’s difficult to establish if Rivera was thinking about Zapata in 1915.

Motherhood – Angelina and the Child (1916)

| Date Completed | 1916 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 132 cm x 86 cm |

| Current Location | Museo de Arte Alvar y Carmen T. de Carrillo Gil |

The Madonna and Child is a constant art history topic, and Motherhood is a modernized, Cubist interpretation of it. Angelina Beloff, Rivera’s 12-year common-law wife, embraces their infant son who succumbed to influenza just weeks after his birth.

Rivera’s distinctive attitude to Cubism, eschewed the gloomy, monochrome palette utilized by painters like Pablo Picasso or Georges Braque in favor of vibrant hues evocative of those used by Italian Futurist painters like Giacomo Balla and Gino Severini, is brilliantly illustrated in this work.

Creation (1923)

| Date Completed | 1923 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions | 3.6 meters |

| Current Location | Museo de San Idelfonso, Mexico City |

The muralist artwork is a massive work that spans over a thousand square feet. Diego Rivera’s artwork was the first to be ordered by the government. Between 1922 and 1923, Rivera created this picture. The drawing’s main topic was a strong emphasis on faith, as well as its beliefs. The painting is done with antique techniques, including molten wax, which is used to apply the colors. The drawing comprises a large pipe that is hidden within the frame, as well as different designs that represent something.

The human figures on each side of the deep-colored framework, which evokes an altar, are the drawing’s key highlights.

The depiction of the sun is at the highest position above all the details. The Divine Trinity is symbolized by three hands pointing away from the sun in separate directions. All of the hands appear to be pointing down at the sketched human features. Another artwork behind the altar depicts a man stretching out his hands as if attempting to reach out to all the others. The depiction of a person with completely spread-out hands is right beneath the sun.

Eve and Adam are seated on opposing sides of the altar at the bottom of the image. Eve and Adam are human beings who are said to be the first humans by Christians. They are nude, contrasting the rest of the group, to reflect the Christian idea of rebellion. The nine distinct pictures on both sides of the altar are all indicative of various Christian qualities and virtues as believed in religious beliefs. They signify love, optimism, and belief, starting from the left.

Individuals on the right signify wisdom, fairness, and the belief in one’s own power.

The picture and its symbolism are solely religious and have no political overtones. The illustration also represents the living values that are taught in the Christian faith. The artist was dissatisfied with this painting since it exhibited a lot of Italian techniques.

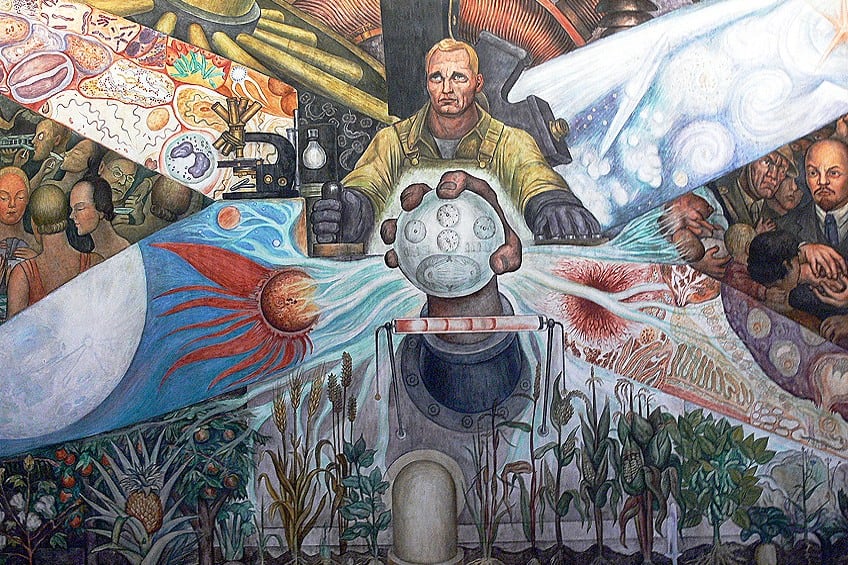

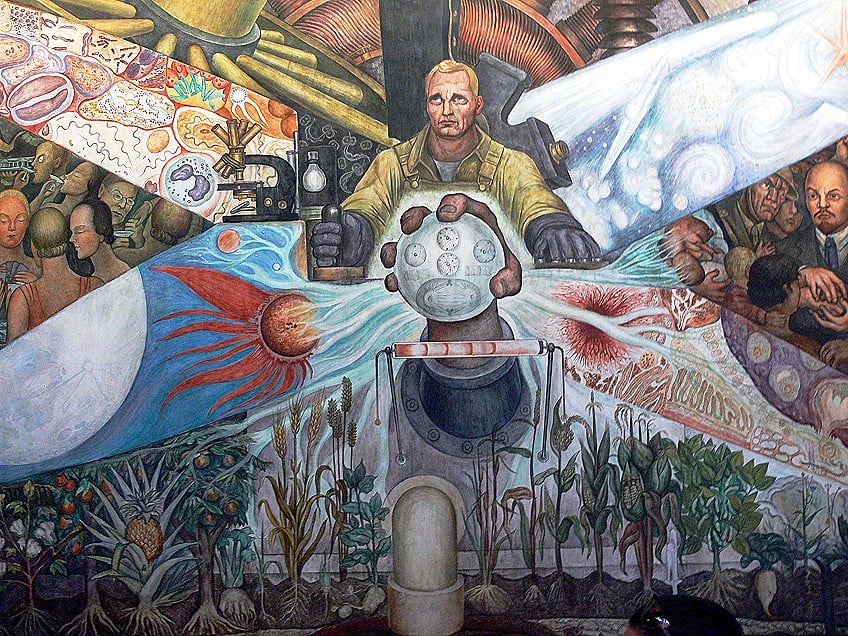

Man, Controller of the Universe (1934)

| Date Completed | 1934 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions | 485 cm x 114 cm |

| Current Location | Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City |

The picture depicts the human species “at the crossroads” of reinforcing or opposing forces and ideologies: science, industry, Communism, and capitalism, as its title suggests. The painting depicts a heroic worker encircled by four propeller-like razors in the middle, disclosing Rivera’s commitment to Communism.

It stands in contrast to a ridiculing depiction of society women with a compassionate depiction of Lenin encircled by communists of various races on the right. The Mexican state ordered this artwork, which is a smaller but almost identical replica of the Rockefeller mural, Man at the Crossroads, for the Rockefeller Center.

A year before this piece, the New York City artwork was demolished due to criticism about Rivera’s picture of Lenin and his following unwillingness to erase the image.

Portrait of Lupe Marin (1938)

| Date Completed | 1938 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 171 cm x 122 cm |

| Current Location | Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City |

Diego Rivera’s political and social life was as vibrant as his work career as he became a well-known worldwide artist. Diego Rivera, like many other young academics in the 1920s, was a Marxist idealist, thus it was only natural that he chose companions who shared his ideals. Diego Rivera publicly joined the Mexican Communist Party towards the end of 1922, after the Russian Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 had transformed Marxism into Communism.

His first spouse, whom he wedded in 1923, was a Communist who he met through another young Communist female acquaintance.

Lupe Marin shared more than just his political ideals with Diego. She was an unusual beauty brimming with irrational emotions. Unfortunately, her ferocious envy of Diego Rivera was too much for his passionate nature to handle. When Diego Rivera paid the smallest attention to other ladies, she tore up his sketches in a fit of wrath on several occasions. Diego Rivera, without a doubt, inflamed Lupe for his own fun at the start. She crushed up a valued statue and served it to him in his soup, even though she was jealous of his enthusiasm for Pre-Columbian sculpture.

Rivera demonstrates his significant creative debt to the European painting heritage in this stunning picture of Lupe Marin, from whom he had been estranged for the preceding decade.

Rivera presents his figure partially in reflection by using a mirror in the backdrop, a technique used by artists like Claude Monet, Diego Velázquez, and Paul Gauguin, which he would later utilize in his 1949 portrait of his daughter Ruth. The model’s expressive hands and the painting’s coloring recall another creative hero, El Greco, while the structure and composition recall Paul Cézanne’s work.

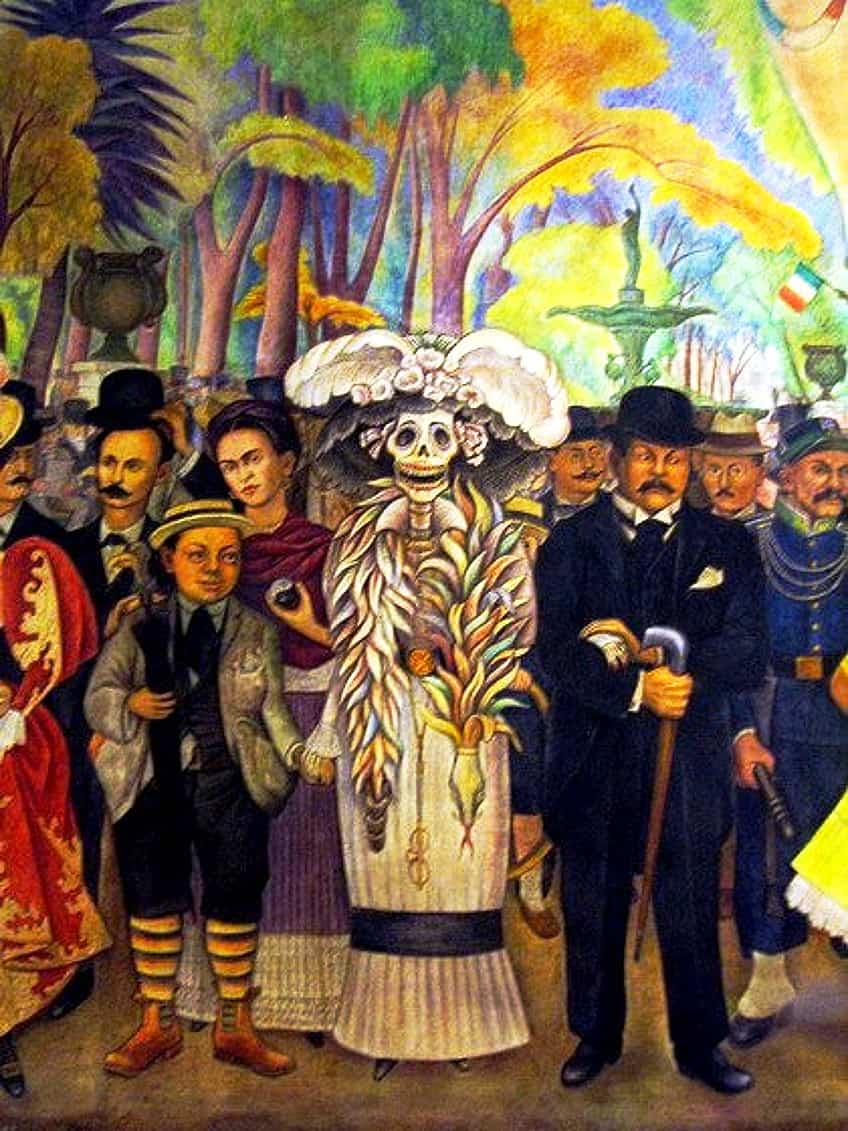

Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park (1947)

| Date Completed | 1947 |

| Medium | mural |

| Dimensions | 15 meters x 1.7 meters |

| Current Location | Museo Mural Diego Rivera |

Could it be that the artist, a big man who called himself “the toad” and defined himself as “ugly,” disliked looking at himself? Diego Rivera’s self-portraits always include bulging eyes and a somewhat sarcastic smirk. The painter’s self-effacement is visible even in a seemingly harmless insertion of a Diego Rivera self-portrait, such as the one surreptitiously incorporated in this vast fresco.

Diego Rivera is shown as a child, with his wife Frida standing behind him as an adult, alluding to Rivera’s inexperience in their relationship.

Compare this to Frida’s love portrait of their union on a 1931 canvas. Hundreds of figures from Mexico’s 400-year history congregate in Mexico City’s largest park for a promenade. The dream’s darker side is revealed by the colorful balloons, immaculately dressed guests, and diversified wares vendors: a conflict between an indigenous household and a law enforcement officer; a man firing a gun into the face of someone being crushed by a horse in the middle of a brawl; and a nefarious skeleton grinning at the spectator.

This is a complicated dream in the style of Surrealism. Dreams were the primary subject matter for Surrealists such as Salvador Dalí. Because dreams are so intimate and unique, artists were able to juxtapose seemingly unconnected objects, such as clocks and ants in Dalí’s case.

Despite the fact that Rivera never formally joined the Surrealists, he employs this method in this piece, in which he cobbles together a tableau made up of various historical figures.

Recommended Reading

Today we took a look at Diego Rivera’s biography as well as some prime examples of Diego Rivera’s artworks. If you would like to discover even more about Diego Rivera’s paintings and lifetime, then why don’t you check out our list of recommended books. These will assist you in finding out as much as you want about this famous Mexican artist.

Diego Rivera: His World and Ours (2011) by Duncan Tonatiuh

Duncan Tonatiuh, an award-winning novelist and artist who has been fascinated by the culture and art of his home Mexico, wonders what history Diego Rivera might tell via his paintings if he were still painting today. What kind of narratives would he be able to bring to life? Tonatiuh helps younger audiences comprehend the value of Diego Rivera’s paintings and understand that they, too, can tell stories via art by taking inspiration from the artist.

- Helps young readers understand the importance of Rivera’s art

- Discover the life and legacy of the celebrated Mexican artist

- A Pura Belpré Illustrator Award winner

Diego Rivera (2022) by Francisco de la Mora

The unusual lives and times of an artist for whom mythology and reality merged are told in this brilliantly produced graphic novel. In more ways than one, Diego Rivera was a groundbreaking painter. By his thirties, he had established himself as one of the most significant players in the Parisian art scene, having started painting school at the age of eleven. Rivera’s tireless work ethic was matched by his boundless enthusiasm for life, which he demonstrated by amassing scores of lovers and four brides.

Diego Rivera was a worldwide art superstar at the height of his career. He received his training in Mexico City’s Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes and spent several years in Europe, where he rose to prominence in Paris’s thriving global community of avant-garde artists. He created his own form of cubism there, filled with emblems of Mexican national identity. Following his return to Mexico in 1922, he joined other creative intellectuals and government leaders in a coordinated attempt to rejuvenate and reinvent Mexican culture in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution, a 10-year battle that claimed the lives of over a million people.

Take a look at our Diego Rivera paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Diego Rivera?

Rivera was a well-known proponent of Mexican Muralism, a government-sponsored movement intended at praising the country’s history, heritage, and post-Revolutionary principles via large-scale murals in public settings. Rivera produced vast mural cycles that relied on modernist painting approaches to convey heroic views of Mexico’s history and present that grabbed the notice of critics and observers worldwide, employing a centuries-old fresco method. Rivera’s work and ideas were notably well received by artists and viewers in the United States.

When Did Diego Rivera Die?

On the 24th of November, 1957, Diego Rivera died of cardiac failure. He passed away in the morning time in his house in Mexico. He was 70 years old at the time. In the 1940s, Rivera was diagnosed with diabetes. Two years prior, information about his disease had slipped out, and he traveled to Moscow for treatment by Soviet physicians.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Diego Rivera – Discover the Life and Legacy of Diego Rivera’s Art.” Art in Context. June 28, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/diego-rivera/

Meyer, I. (2022, 28 June). Diego Rivera – Discover the Life and Legacy of Diego Rivera’s Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/diego-rivera/

Meyer, Isabella. “Diego Rivera – Discover the Life and Legacy of Diego Rivera’s Art.” Art in Context, June 28, 2022. https://artincontext.org/diego-rivera/.