Caravaggio – Baroque Master of Chiaroscuro and Tenebrism

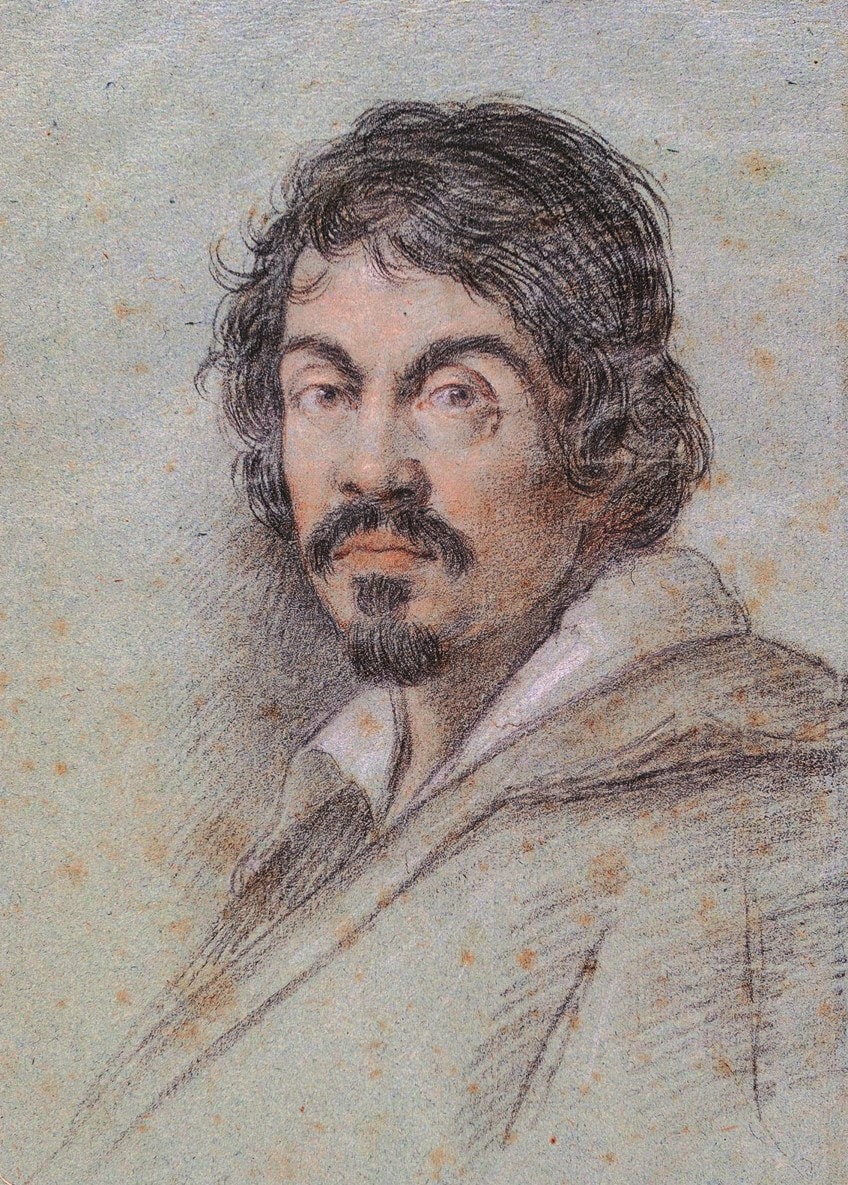

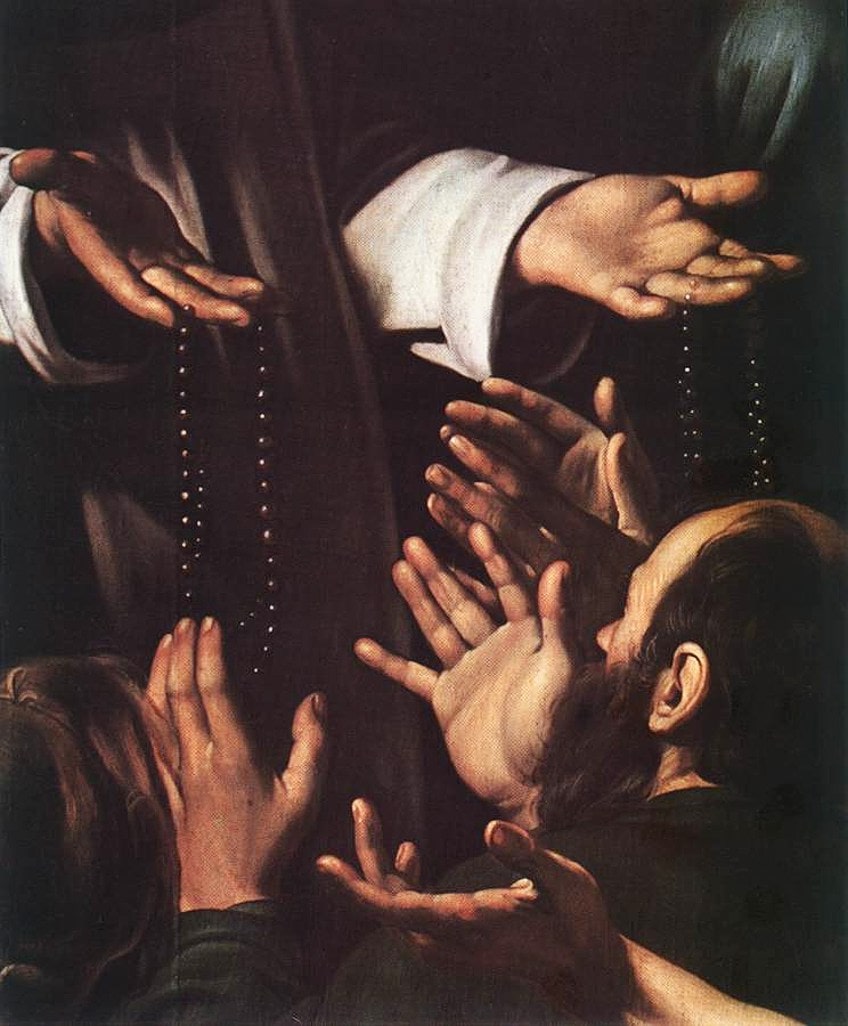

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio is regarded as one of the most significant and revolutionary Italian Baroque artists of his era. Caravaggio’s paintings broke with the conventions that had led a generation of artists who glorified both individual and spiritual experiences. Caravaggio’s artworks are widely renowned for their incredible display of painting techniques such as tenebrism and chiaroscuro.

Table of Contents

Caravaggio’s Artworks and Life

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio moved to Rome, where he became well-known for his tenebrism technique, which used darkness to emphasize lighter sections. Caravaggio was the first of the Italian Baroque artists to adopt chiaroscuro as a prominent aesthetic characteristic, intensifying the shadows and deploying clearly outlined beams of light for emphasis and to enhance the storyline of the painting. The approach became prominent in his later works, and it has since been linked with his more mature images.

| Nationality | Italian |

| Date of Birth | 29 September 1571 |

| Date of Death | 18 July 1610 |

| Place of Birth | Caravaggio, Lombardy |

Childhood

Caravaggio’s biographical material is scant, and what is available has been cobbled together from judicial and provincial records, as well as other surviving sources. Caravaggio’s family had aristocratic links despite their inferior socioeconomic rank. Caravaggio’s aunt had been a wet nurse to the offspring of Sforza aristocracy, and relatives of the Sforza dynasty.

Milan was hit by a bubonic plague epidemic in August 1576, when Caravaggio was around five years of age. Despite his family’s escape to the Caravaggio hills, many of his relatives all perished of the plague by October 1577. Caravaggio relocated permanently to Milan, where he sustained himself via his portrait paintings when the family estate was split and sold among the other children.

Early Training and Work

It is likely that Caravaggio began his creative career with familiarity with Renaissance painters. Moretto, Savoldo, Lotto, Palma Vecchi, Giorgione, Titian, and Leonardo da Vinci all had an effect on Caravaggio’s art. Caravaggio very definitely had Classical training and was familiar with significant books of the time. Caravaggio would have read Vasari’s words and drawn inspiration and motivation from them for some of his works. Milan in the late 16th century was a frightening, violent town, making it an ideal location for the young, rootless, damaged, and perhaps hot-headed artist to be tempted and provoked.

After being involved in a murder, the artist traveled to Rome in approximately 1592, where he stayed until around 1606.

Caravaggio served as an apprentice to the painter Giuseppe Cesari, a well-known fresco painter, for several months here. While working for Cesari, Caravaggio mostly produced background fruits and flowers; from this practice, he gained an eye for detail and an appreciation for the intricacies of still-life paintings, which can be seen in the meticulous portrayal of fruits and vegetation in his later works.

Following his apprenticeship with Cesari, Caravaggio met his subsequent supporter, Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte. Del Monte provided Caravaggio with shelter, sustenance, and creative jobs, as well as connecting him to painting collector groups. Other prestigious Roman painting purchasers, such as Marchese Vincenzo Giustiniani, were drawn to the subject matters of Caravaggio’s initial works, such as festivities of music, still lifes, and seductive characterizations of young men like Amor Vincit Omnia (1602), which portrays a lifelike, bare cupid astride icons of battle, scientific knowledge, music, and literary works.

These religious and secular compositions landed him significant Roman sponsorship and launched him to creative acclaim.

Mature Period

Cardinal del Monte assisted him in obtaining his debut significant official works project, the decorating of the Contarelli Chapel, in 1599. A second assignment quickly followed, to decorate the sidewalls of Santa Maria del Popolo’s Cerasi Chapel. With these assignments, the painter began the dramatic reimagining of heavenly figures that would become a defining feature of his career.

Caravaggio humanized celestial figures by depicting them as common people.

Caravaggio used this technique to criticize and disrupt the immaculate, idealistic images of the Italian Renaissance era, as well as Roman classical styles. Judith Beheading Holofernes (c. 1602) and Death of a Virgin (1606) are two examples of this style.

The latter picture had a major impact on other painters, notably Artemisia Gentileschi, who painted several representations of the same subject matter. The naturalism of Caravaggio’s religious works, as well as the contrast of holy beings with contemporary, 17th-century interiors, enraged several critics. Many of Caravaggio’s artworks were declined by contracting institutions due to profane or immoral depictions.

Caravaggio’s stay in Rome came to a tragic conclusion. Court records show that Caravaggio was engaged in a slew of progressively violent skirmishes and accidents and that he was frequently shielded from punishment by witnesses who were hesitant to disclose the artist’s participation for fear of repercussions from the artist’s powerful and distinguished clients. Caravaggio began a confrontation with a waiter over his order of artichokes in 1604, in which the painter battered the victim’s face with a dish in one of the more vivid instances.

Caravaggio’s rage, legal troubles, and violent behavior reached a peak on May 28, 1606, when he murdered his old companion Ranuccio Tomassoni, presumably in the setting of a fight.

Caravaggio departed Rome before official accusations were brought against him for the murder; he was condemned to permanent banishment from the city, convicted as a murderer, and subjected to a death sentence that permitted anybody in the papal powers to obtain a monetary reward for murdering him.

Late Period

After that, the painter stayed nine months in the city of Naples, starting in September 1606. During this time, Caravaggio started to dabble with colors, taking inspiration from Venetian artists such as Titian. Caravaggio relocated to Malta around 1607, and it is likely that he was granted safe exit by Fabrizio Sforza Colonna, son of his guardian Costanza Colonna. During his time in Malta, Caravaggio achieved immense success and notoriety, and on the 14th of July, 1608, he was initiated into the Order of the Knights of Malta.

His paintings from this time are notable because he began to create with progressively quick brushstrokes and used reddish-brown tones more extensively.

Caravaggio was involved in a violent, deadly altercation at the apartment of the Conventual Church of St. John’s organist a month after receiving his title. Caravaggio’s criminal incarceration, break out from jail, and departure to Syracuse in the fall of 1608 were all the outcomes of this turmoil. On December 1, 1608, the Knights of Malta canceled the artist’s awards in his absence.

Caravaggio moved from Syracuse to Palermo before returning to Naples in 1609. Armed thugs sliced the artist’s face in Naples for unexplained reasons, leaving Caravaggio with near-fatal injuries.

He stayed recovering in the palace of Constanza Colonna’s until July 1610 after this occurrence. After discovering that one of his famous benefactors had obtained a papal amnesty for him, Caravaggio sought to return to Rome. He was caught and put in a holding cell for two days when he arrived in Palo. Caravaggio died of a fever, perhaps malaria, shortly after his discharge, on the 18th of July, 1610.

Legacy

Caravaggio has been described as either a late Mannerism exemplar or a forerunner of the Baroque era. Caravaggio was a significant creative impact both in his day and now, despite the fact that only twenty-one pieces have been definitely assigned to him. Other Roman painters began to replicate his characteristic technique by 1605, and soon after, artists outside of Italy, including Rembrandt and Diego Velázquez, used Caravaggio’s dramatic lighting effects into their own, iconic works.

Caravaggio’s style immediately garnered committed admirers, known as “Caravaggisti”, who filled their creations with Caravaggio’s attributes.

Caravaggio’s paintings influenced notable poets of the time, like Cavalier Giambattista Marino. Despite praise during his lifetime and quickly after, Caravaggio’s legacy was all but forgotten by the 18th century, with the exception of modest attention from Neoclassical artists such as Jacques-Louis David. The modern and contemporary obsession with the artist is partly owing to the work of Roberto Longhi, whose 1951 Milanese show and 1952 Caravaggio monograph reintroduced and solidified the artist’s present prominence.

The theatrical features of Caravaggio’s works, as well as his cinematic lighting, allow for an easy transition to film, and directors such as Martin Scorsese and David LaChapelle have mentioned him as an inspiration in their work.

They have absorbed the strength and directness of Caravaggio’s photographs in this, leveraging his representations of flawed bodies and his capacity to weave a story from viewpoint of climax to engage spectators within their own narrative media. Caravaggio is now regarded as one of the Great Masters who is most obviously “Modern”. Aside from compositional advances, Caravaggio’s legacy has also been linked to the purportedly queer content of his works, which has been seen as a symbol of his own probable homosexuality.

The depiction of Caravaggio’s androgynous, sensuous, partially clad, or nude young men through the prism of gay desire is a contentious subject in Caravaggio studies. Some writers, such as Graham L. Hammill and Donald Posner, state explicitly that works like these reflect gay sensuality and seduction.

Other scholars, such as David Carrier, argue that contemporary interpretations of the creator’s homoerotic substance idiosyncratically ascribe it to the 16th and 17th centuries, as well as 20th-century rules and conceptions about queerness and visual interpretation.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s Paintings

Caravaggio’s popular depictions of religious people were pioneering, depicting scriptural figures in a non-idealized manner by including evidence of aging and destitution, as well as the use of modern attire. This helped to demystify the sacred and make it more accessible to the general populace. Caravaggio’s art embodied a kind of religious egalitarianism in this way.

Self-Portrait as Sick Bacchus (1594)

| Date Completed | 1594 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 67 cm x 53 cm |

| Current Location | Galleria Borghese, Rome |

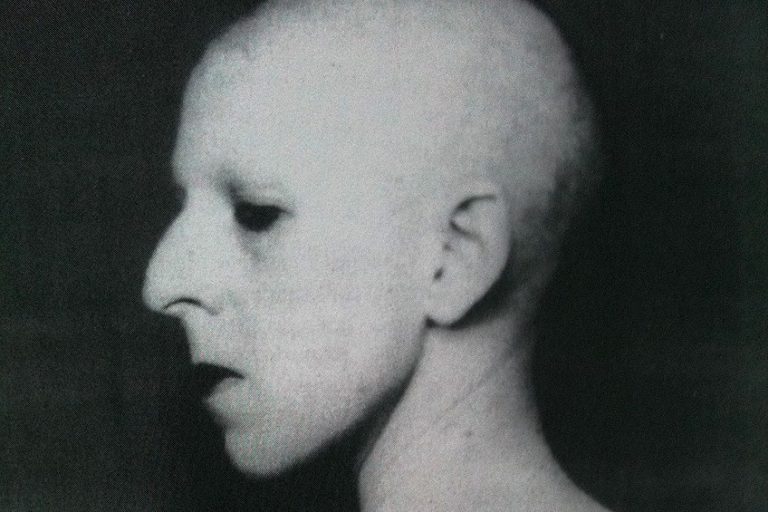

Caravaggio’s portrait was most likely produced while under the guidance of fresco artist Giuseppe Cesari, and the painting’s skillfully crafted still life components reflect Cesari’s influence. The figure’s uncomfortable position, as though rotated to guarantee greater vision in the mirror surface, is confirmed by Caravaggio’s 17th-century historian Giovanni Baglione’s identification of this picture as one of a set of the artist’s early self-portraits created with the aid of a convex mirror.

Sick Bacchus, a seemingly appropriate name for the subject’s complexion and dark, sunken eyes, is ascribed to art historian Roberto Longhi, who claims the painter created it after being discharged from the hospital after sustaining horrible wounds after being kicked by a horse.

The image’s greenish coloration could also be attributed to a nighttime setting, which would be suitable for the bacchanalia that was about to take place. Bacchus was an appropriate alter-ego for Caravaggio since he was the god of wine, theater, and ritualistic demonstrations of ecstasy, as well as inspiration and devastation. The painting, on the other hand, contrasts from typical depictions of Bacchus, which show him in the middle of wild revelry, frequently amid a beautiful environment.

The painting follows the traditions of many of Caravaggio’s earlier works, showing the legendary figure in a minimalist interior.

Furthermore, the artist’s complexion and passive attitude imply the repercussions of over-consumption rather than a god in his peak, celebrating the benefits of wine and revelry. The ivy leaves surrounding the artist’s head have started to wither, a couple of the fruits in his hands have shrunk, and the two juicy apricots in the painting’s foreground have started to spoil.

Boy Bitten by a Lizard (c. 1594)

| Date Completed | c. 1594 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 65 cm x 52 cm |

| Current Location | National Gallery, London |

A boy flinches in pain and astonishment after reaching for one of the fruits on the table only to be attacked by a lizard hidden amid the pile of cherry, an example of the unkempt, curly-haired adolescent that filled many of Caravaggio’s early secular paintings. Despite Caravaggio’s condemnation of Classical statuary, the boy’s emotion may be based on the expression of sheer terror discovered in the monument of Laocoön and His Sons, and the reptile is evocative of the reptile depicted in the old Roman statue Lizard Apollo, which would’ve been in Rome during Caravaggio’s time.

Caravaggio exhibits his ability to represent the movement of light over and through many materials on the table.

The youngster dwells in a bland, timeless room, with blank walls accented only by a sharp, diagonal light source emerging from the upper left, and beyond the frame of the picture, in line with Caravaggio’s larger style. This emphasizes the boy’s naked right shoulder, elevated as he winces from the attack; his furrowed forehead and lips open in a gasp, heightening the piece’s emotional expression.

The work’s stunning sexual undercurrent is one of its most noteworthy features.

Bitten fingers were an emblem of an injured phallus in Caravaggio’s period, and the creator’s use of jasmine, a classical emblem of sexual desire, along with the reptile languishing underneath the fresh fruit, both symbols of seduction, implies that the painting depicts the dangers of luxuriating in sexual appetites.

The Musicians (1595)

| Date Completed | 1595 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 92 cm x 118 cm |

| Current Location | Metro Museum of Art |

This painting is a “concert” picture, a Venetian pictorial genre represented by Titian’s earlier 1510 masterpiece, The Pastoral Concert, in which artists honored the performance of music. This picture challenges classical explanations of the subgenre in several ways: it portrays a practice session rather than a live show, and the incorporation of the musicians’ traditional garments and a cupid in the topmost left of the image suggests a symbolic intention to interconnect music, romance, and liquor (symbolized by the fruit in the cupid’s fingers).

The crowded people in the image appear to have been sketched individually and then incorporated into the composition.

Caravaggio’s associate Mario Minniti is the central musician, while the other person facing the spectator is perhaps a self-portrait. The musicians are practicing madrigals, and the lute player in the middle is transfixed by the music, his misty eyes and dreamy look implying melancholy and unrequited love.

The existence of another musician is indicated by the presence of a violin in the front.

Cardinal del Monte, Caravaggio’s patron and the person who commissioned this piece, was a musician who educated musicians and promoted musical creativity. The Musicians‘ packed area may evoke the musical environment present in del Monte’s home.

Medusa (1598)

| Date Completed | 1598 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 60 cm x 55 cm |

| Current Location | Florence, Uffizi |

Medusa, the Gorgon monster from Greek mythology whose hair was formed of snakes and whose glance turned spectators into stone, is shown in this picture. Medusa was eventually destroyed by the hero Perseus, who decapitated her using his shield’s mirror as a guide. Caravaggio represents Medusa breathing her last breath, soon following her beheading.

The painting is unusually painted on a circular canvas spread over a convex wood backdrop. This is modeled after Perseus’ shield and displays Medusa’s dying moments on its polished surface.

It also refers to the practice of sketching Medusa on shields before combat to represent triumph over overwhelming odds. Caravaggio is supposed to have used himself as the source for the work, and Medusa, as a self-portrait, is an excellent illustration of the artist’s play with sexuality and androgyny. Caravaggio utilized actual snakes, ordinary water snakes local to the Tiber River, to depict Medusa’s twisting vipers, in line with his goal in capturing the world as it looked and drawing from life. The green of leaves and the backdrop contrast sharply with the scarlet blood of the chopped head, emphasizing the image’s brutal and visceral character.

The artwork was sent as a gift by the creator’s sponsor to Ferdinando I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and was favorably welcomed by the Medici family, who displayed it prominently.

The Calling of St Matthew (1600)

| Date Completed | 1600 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 60 cm x 55 cm |

| Current Location | San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome |

Caravaggio’s initial significant public works job was to paint the lateral wall of the Contarelli Chapel in the Roman cathedral San Luigi dei Francesi. It is accompanied by two companion pieces representing various incidents from St. Matthew’s life, one of which is The Martyrdom of St Matthew. Caravaggio presents a scene from the Gospel of Matthew in which Christ, joined by St Peter, invites the tax man Matthew to become a follower of Christ.

Matthew’s identity has been differently identified. Most interpretations attribute Matthew to the bearded key character, whose motion, a hand with an outstretched finger gesturing towards his breast, appears to inquire “who, me?” Others have speculated that Matthew is the younger man with the lowered head at the far end of the table, which might be an intended ambiguity. This piece has also been given a political connotation.

Graham-Dixon sees St. Matthew’s delayed rising from “divine sleep by the arrival of Christ” as a reference to the French king’s transformation, completed about 1600, the year the French monarch Henri IV married Marie de’Medici.

This picture exemplifies two of the artist’s stylistic characteristics: his portrayals of holy people in the appearance of modern-day Romans, and his distinctive use of light. The persons at the table are costumed as citizens of the early-17th-century middle classes, while Jesus and St. Peter are clothed more modestly and barefoot; the features are naturalistic and non-idealized.

The sole iconographic hint to the scene’s sacred background is a thin, foreshortened gold halo over Christ’s head, which is partially concealed by the diagonal beam of dazzling light.

Because of these features, critics were outraged by the artwork and accused the artist of sacrilege. Though Caravaggio included a prominently positioned open window in the painting, it does not give light; rather, the brilliance emanates beyond the picture frame and is implied as an unearthly companion to Christ and St. Peter’s heavenly presences.

Caravaggio employed this dramatic light source to include the chapel area into the painting’s atmosphere. Though its source is not apparent in the image, the top right light source was intended to link to the chapel’s natural illumination and was an extension of the light emerging from a glass immediately above the church altar. As a result, the artist established consistency between the scenario of Matthew’s summoning and the church in which it was set.

The Entombment (c. 1604)

| Date Completed | c. 1604 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 300 cm x 203 cm |

| Current Location | Vatican City |

The Entombment was created for the Oratorian cathedral of Santa Maria in Vallicella in Rome. Mourners carry Christ’s body to the burial site, with John the Evangelist holding Christ’s torso and Nicodemus carrying Christ’s legs. A distraught Mary of Clopas, a tearful Mary Magdalene, and a bowed Virgin Mary accompany Christ to his burial.

The individuals are shown with a realism that exposes their religious relevance, like in Caravaggio’s previous work, and this is enhanced by the image’s red and brown tones (characteristic of Caravaggio’s palette at the period), which assist to underscore the participants’ earthy normality.

The design is likely influenced by Michelangelo’s 15th-century Pietá in St. Peter’s Basilica since Christ’s lifeless body, drooping arm, and foreshortened torso and head reflect Christ’s stance as can be seen from the front of the statue. The composition of the artwork is structured in a striking diagonal, with people aligned in a drop from the upper right corner to the bottom left corner.

Each figure depicts the development of feeling in proportion to their place in the artwork. Mary of Clopas’s extended arms and wide palms occupy the peak of the diagonal, expressing her immediate emotion of incredulity and anguish at Christ’s killing. The composition then descends to a sobbing Mary Magdalene, her face hidden from view; the Virgin Mary’s resigned, bowed head; and Nicodemus, laboring under Christ’s weight. He turns to face the audience as if to ask, “What’s next?”

The question has been answered by John the Evangelist, who concentrates on Christ himself, whose countenance of tranquility, calm, and inevitability of death accomplishes the emotive arc of the picture.

The picture was intended to be hung over an altar, and the stone tomb in the scene is shaped and seems similar to the altar. As a result, Caravaggio stretches the burial scene into the worshipers’ area, and the frontal source of light far beyond the plane of the picture appears to emerge from the altar itself – a heavenly light of resurrection energizing and bringing hope to the funeral scene above.

The Beheading of St John (1608)

| Date Completed | 1608 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 370 cm x 520 cm |

| Current Location | St. John’s Co-Cathedral, Valetta, Malta |

This altarpiece for the Oratory of San Giovanni Decollato is often regarded as Caravaggio’s best work. Caravaggio’s “passaggio,” a gift customarily presented upon membership into the Order of the Knights of Malta, is widely regarded as one of his greatest works. This picture is notable since it is Caravaggio’s only signed work. The artist’s signature as “Fra Michael Angelo”, a centered signature that denotes the artist’s new social rank as Michelangelo, Knight of Malta, seeps into the blood streaming from John’s skull.

Scholars have interpreted Caravaggio’s blood mark as an act of remorse, with the artist confessing his guilt and acknowledging his role in the death of his companion, the incident that triggered his escape and exile from Rome.

The characters are grouped tightly, like in other paintings from his Malta time, leaving wide swaths of unoccupied or less filled space above and near to the center of the action. As a result, even though the artist imbues each performer with a distinct feeling or reaction, individuality is subjugated to the collective depiction of the climactic moment. The old woman is the only figure in the photograph who expresses a significant emotion. The artist’s tenebrism casts much of her face in shadow, but Caravaggio emphasizes her hands, which are gripping her head in fear.

The emotional counterpart to the peaceful, departed St. John, and, by proxy, to the quiet of the acts of witness that characterize the rest of the characters, is the elderly woman.

Recommended Reading

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was one of the most significant Italian Baroque painters. Would you maybe like to discover even more about his life and art? Here are a few books that you are welcome to check out to get an even better grasp of Caravaggio’s artworks and lifetime.

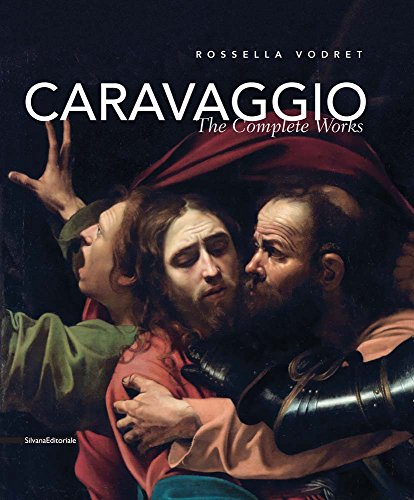

Caravaggio: The Complete Works (2018) by Rosella Vodret

Caravaggio’s advancements would include big changes from eeriness dark to investigating light with negligible differentiation in between a realism that reveals all the weaknesses and furrows of human flesh, rejecting Michelangelo’s idealized version of bodies. It is a clinical description of almost insufferably tense emotion; and the graceful portrayal of critical points on the verge of unfolding. Caravaggio’s artworks, on the other hand, were hugely influential and controversial during his lifetime. Each of his ideas challenged the dominant trends of the day in some manner.

Caravaggio. The Complete Works. 40th Ed. (2021) by Sebastian Schutze

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, was always a dreaded name. The artist was a well-known and contentious bad boy of Italian painting: a guy with a fiery temper, rigorous skill, a creative genius, and a man on the run. He is currently acknowledged as one of the most influential figures in art history.

Caravaggio’s colossal artistic achievements have enthralled audiences for centuries, but his tumultuous personal life – the assassination of Ranuccio Tomasini, the debate over Caravaggio’s sexual orientation, the sequence of events that started with his incarceration on Malta and finished with his untimely death – has long perplexed historians. Few painters have had a criminal history like his, and even fewer have faced the death penalty – but he became a mystic when he painted. His virgins and saints were modeled by prostitutes, yet his paintings are highly spiritual.

Take a look at our Caravaggio paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was Caravaggio’s Paintings Renowned For?

Caravaggio stunned his contemporaries by presenting the martyrs and heroines of Christianity with the bodies and faces of his associates and lovers. He expressed his personal wants and spiritual difficulties to a degree no one had ever believed possible. He was well-known for his use of techniques like tenebrism and chiaroscuro.

What Art Did Caravaggio Create?

He created both spiritual and secular art. Caravaggio was the first of the Italian Baroque artists to adopt chiaroscuro as a prominent aesthetic characteristic, intensifying the shadows and deploying clearly defined shafts of light for intensity and to enhance the storyline of the painting. The technique grew more prevalent in his later works, and it has since been linked with his more mature imagery.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Caravaggio – Baroque Master of Chiaroscuro and Tenebrism.” Art in Context. April 14, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/caravaggio/

Meyer, I. (2022, 14 April). Caravaggio – Baroque Master of Chiaroscuro and Tenebrism. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/caravaggio/

Meyer, Isabella. “Caravaggio – Baroque Master of Chiaroscuro and Tenebrism.” Art in Context, April 14, 2022. https://artincontext.org/caravaggio/.