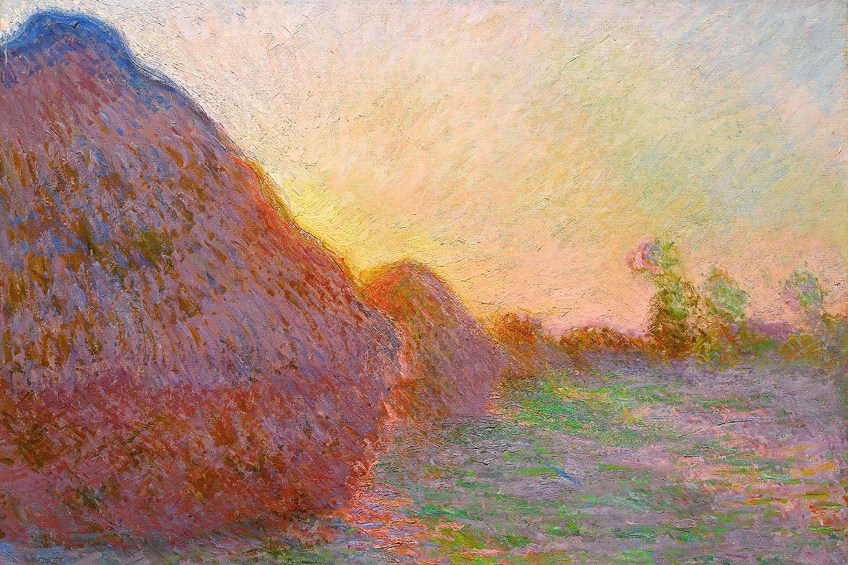

“Haystacks” by Claude Monet – Monet’s Grainstacks at Giverny Paintings

Claude Monet, also called the “Father of Impressionism”, is one of the most well-known serial painters of his time, remembered for his Rouen Cathedral (c.1892-1894) and Water Lilies (1914-1926) series. Among these is his other famous Haystacks (1890-1891) series, which we will discuss in the article below.

Table of Contents

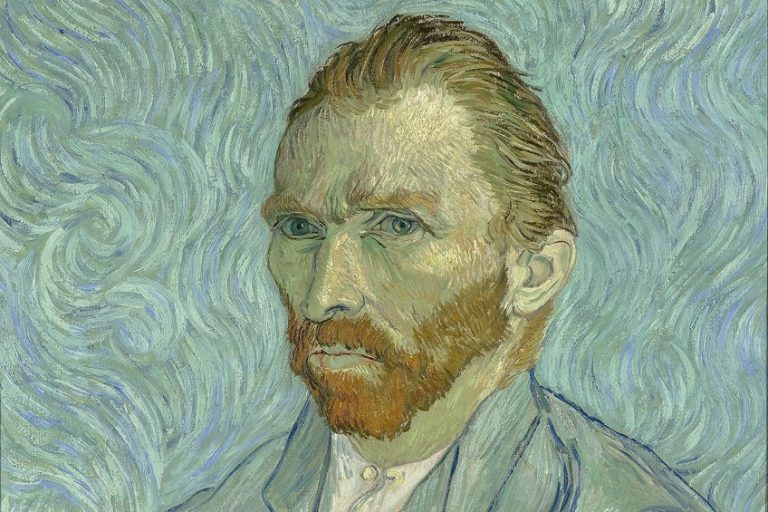

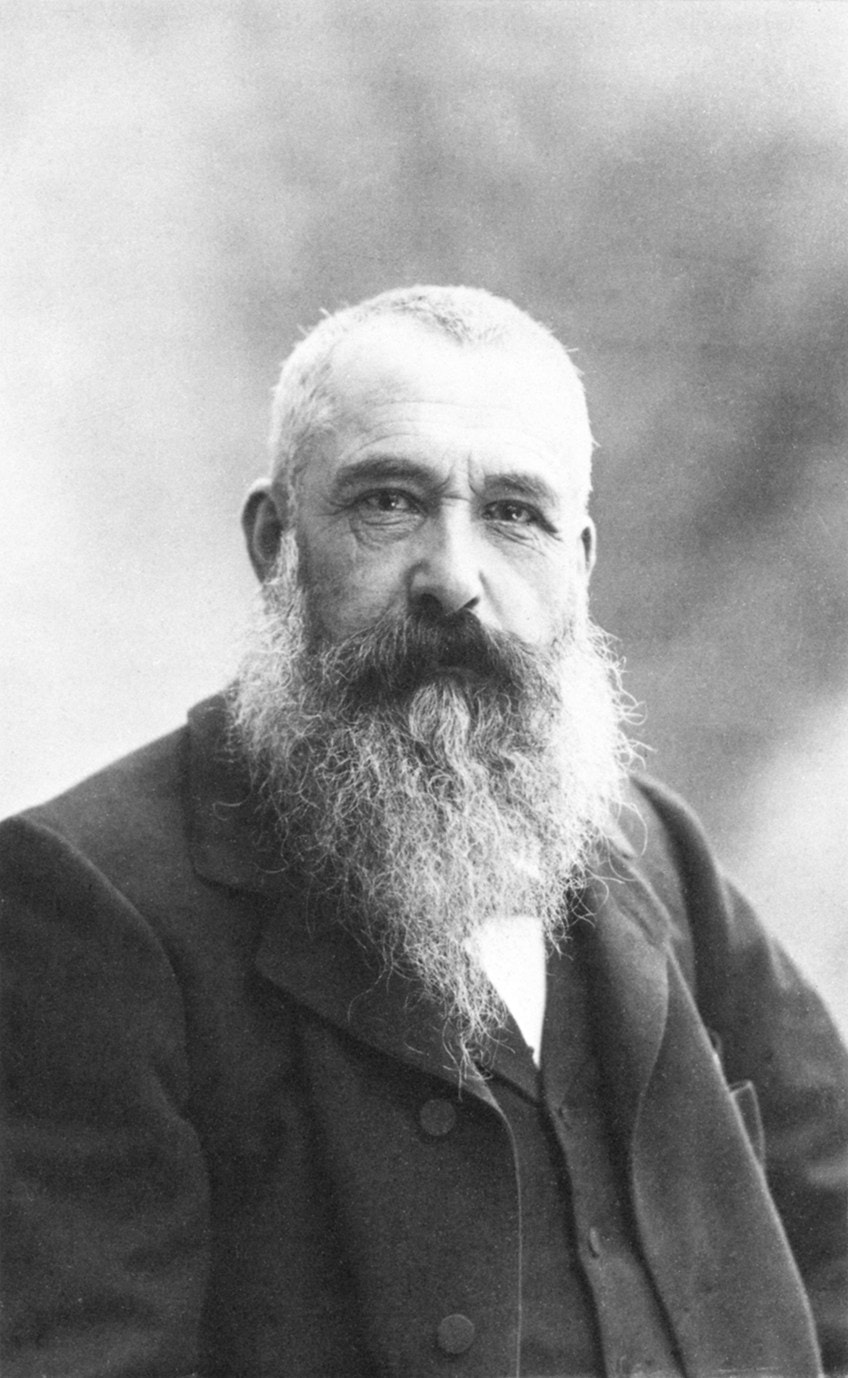

Artist Abstract: Who Was Claude Monet?

Claude Monet was born in France in Paris on December 5, 1926. He loved art from an early age and studied at a school of art in Le Havre, which is where his family lived when he was 11 years old. He also learned from Eugène Louis Boudin, who was a reputed landscape painter and forerunner to the en plein air art style that Monet became famous for. He was married to Camille Doncieux and had two sons, the eldest of whom was Jean and the youngest Michel. After her death, Monet married Alice Hoschedé several years later. He moved to Giverny with his family, where he died on November 14, 1840.

Grainstacks (1890) by Claude Monet in Context

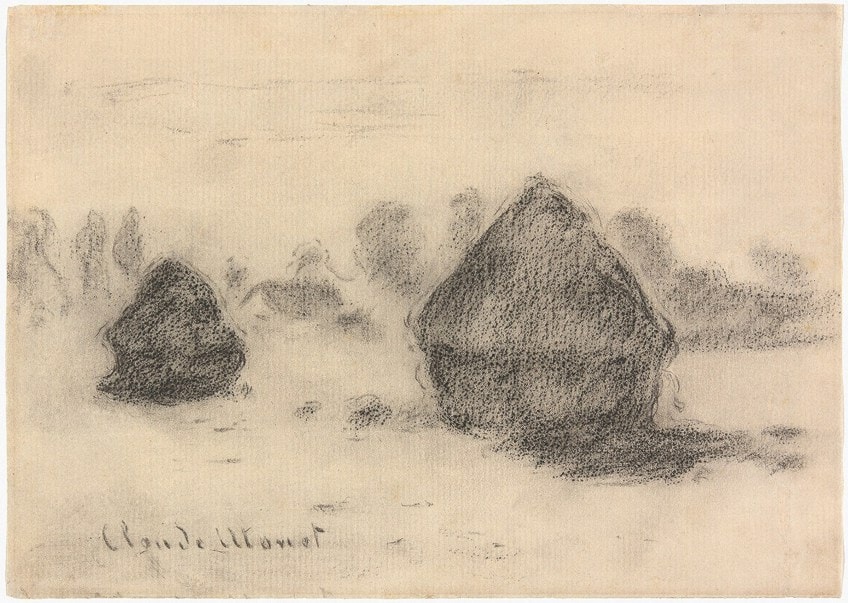

The series of paintings, usually referred to as Haystacks, by Claude Monet consists of around 25 to 30 paintings, which he created between 1890 to 1891. In French, this series has been titled Meules, which means “stack”. In the brief contextual analysis below, we will discuss this series further and where Monet was living when he painted it. This will then be followed by a formal analysis, where we will view and discuss one of the paintings from the series, namely Grainstacks, in more detail.

| Artist | Claude Monet |

| Date Painted | 1890 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Genre | Landscape painting |

| Period / Movement | Impressionism |

| Dimensions | 73 x 92.5 centimeters |

| Series / Versions | From Monet’s Meules series from 1890-1891 |

| Where Is It Housed? | Museum Barberini, Potsdam, Germany |

| What It Is Worth | Sold for $110.7 million at a Sotheby’s auction in 2019 |

Contextual Analysis: A Brief Socio-Historical Overview

As we mentioned above, the series of paintings called Haystacks by Claude Monet was painted around August/September in 1890 to around February in 1891 in Giverny, Normandy, northern France. This is where Monet moved to in 1883 with Alice Hoschedé, his wife, and their eight children, of which several were from previous marriages.

This haystacks painter found inspiration from the natural environment around him, his gardens, and the surrounding landscape, including the wheat fields that were reportedly on the farm belonging to his neighbor, Monsieur Quéruel.

An important point to note when we look at Monet’s Haystacks painting series is that they depict stacks of wheat/grain covered in hay. The hay was used to keep the wheat/grain dry and was typically formed into large “conical” shapes, which were reportedly common shapes in regions of Normandy.

Therefore, when we look at any of the “Haystacks” painting examples, we are looking at what is referred to as “sheaves” of wheat covered by hay, sometimes also straw.

Robert Herbert, who was an art historian and writer, well-known for his research and publications about Impressionism, explained more about utilizing the correct terminology. In Herbert’s publication titled Method and Meaning in Monet from Art in America (Volume 67, September 1979), he explained that haystacks have “slightly irregular, less architectural shapes”, while grainstacks are built with more care. In other words, their “shocks [are] first tied together and then actually thatched to keep the rain out”.

Furthermore, Herbert explained that this was not “ordinary hay”, but “Stacks of Wheat (to give them their real title)”, and henceforth, in the article below, we will refer to Monet’s paintings as either “grainstacks” or “wheatstacks”, utilizing the terms interchangeably, and sometimes utilizing them as an agricultural term and not a title of the painting.

What Inspired the Grainstacks at Giverny?

Although the grainstacks at Giverny had a unique appearance that had an undoubted allure to Monet, to understand part of the inspiration behind why he painted the Grainstacks series, we need to look at him as an artist and what motivated him. Monet was one of the leading artists of the 19th-century Impressionism art movement. His famous oil on canvas Impression, Sunrise (1872) also inspired the movement’s name. Impressionism went against the more conservative norms of painting during this period.

These norms of painting were prescribed by the French Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux-Arts).

The highest-regarded genre of paintings was that of History paintings, and with that came a set of stylistic rules of how paintings should appear. Additionally, paintings were displayed at what was the primary art exhibition called the Paris Salon.

Claude Monet’s set of stylistic rules was far removed from the rules of the Academy. He was known for utilizing the painting technique referred to as en plein air, which means “outdoors” or “in the open air” in French. In other words, he painted outside, in the open air, in natural lighting – he was in the moment. His painting style was also characterized by looser brushstrokes and brilliant colors, exploring the effects of light through these tools.

Therefore, the grainstacks at Giverny became a notable series amongst the collection of Impressionist paintings, exemplary not only of Monet’s love for the outdoors and the unique, natural, forms he observed around him, but also of his artistry to convey colors and light and the ultimate transience of it all.

It is worth noting that Monet also made alterations to some of his paintings when he returned to his studio. This was reportedly so that he could retain the compositional harmony.

Why So Many Wheatstacks?

If we look at Monet’s Wheatstacks paintings, they all share the same subject matter, namely stacks of wheat arranged either as one or two. He was fascinated by colors and light and he wanted to depict the different seasons and weather changes as well as different times throughout the day. This resulted in over 20 paintings of wheatstacks in autumn, winter, and summer, either covered in snow or frost, on an overcast day, in the mist, and in the morning or afternoon sunlight.

Monet showed the atmospheric effects that the natural environment had on the stacks and importantly how the light affected them.

Monet referred to the notion of the “enveloppe” in a letter he wrote to Gustave Geffroy in October 1890. He explained that he was “working away” on a series of “different effects (of stacks)”. However, he found difficulty in keeping up with the fast pace of the setting sun, but he kept working on it even if it required a lot of effort. He wrote further that he wanted to achieve what he described as “instantaneity” above all the enveloppe, being the same light diffused over everything.

What Influenced Monet?

Monet was influenced by Japanese woodcut prints and collected these. We will see this influence from his famous Japanese bridge from his gardens in Giverny. He was influenced by how the Japanese prints conveyed color and perspective.

There was a focus on the minimal subject matter, and it was often more simplistic in nature.

From this, we can deduce that Monet’s Wheatstacks series could have potentially been influenced by some of the stylistic elements employed in Japanese art. For example, the singular use of subject matter, being the stacks of wheat, which were often placed methodically in a position reminiscent of a minimalist style.

Formal Analysis: A Brief Compositional Overview

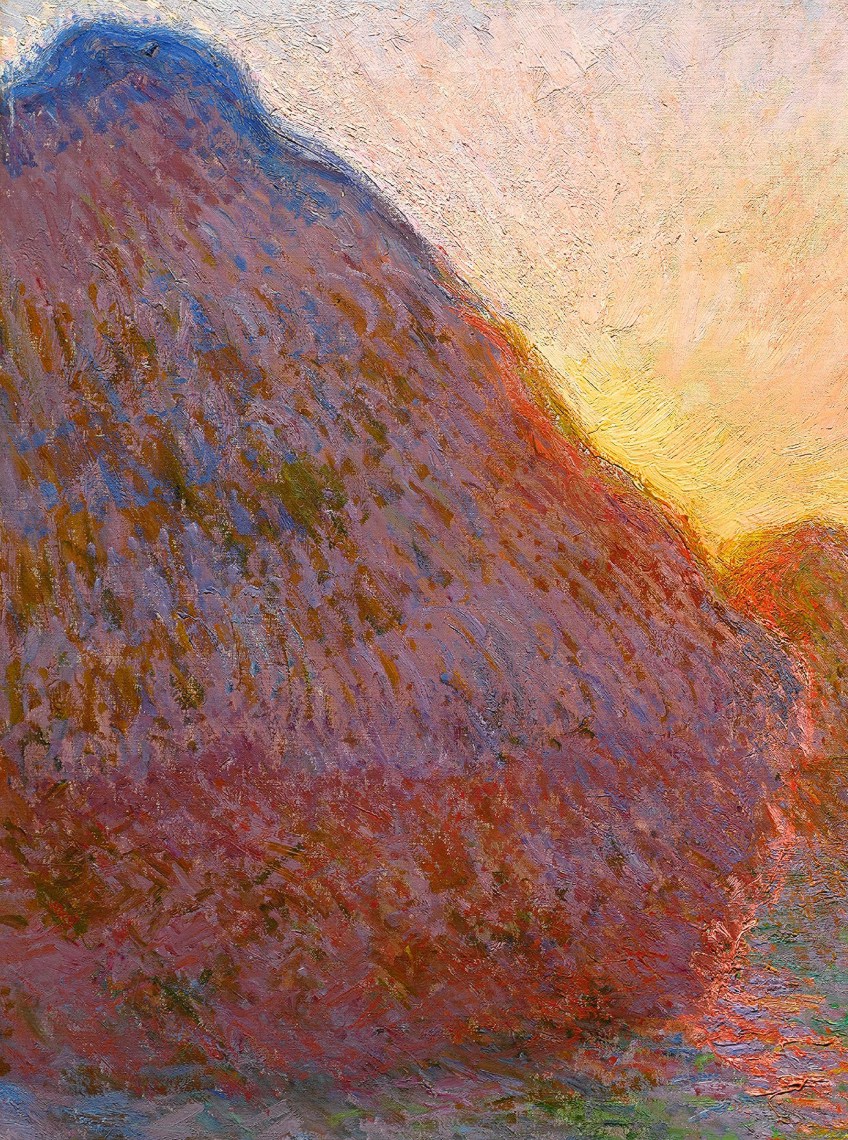

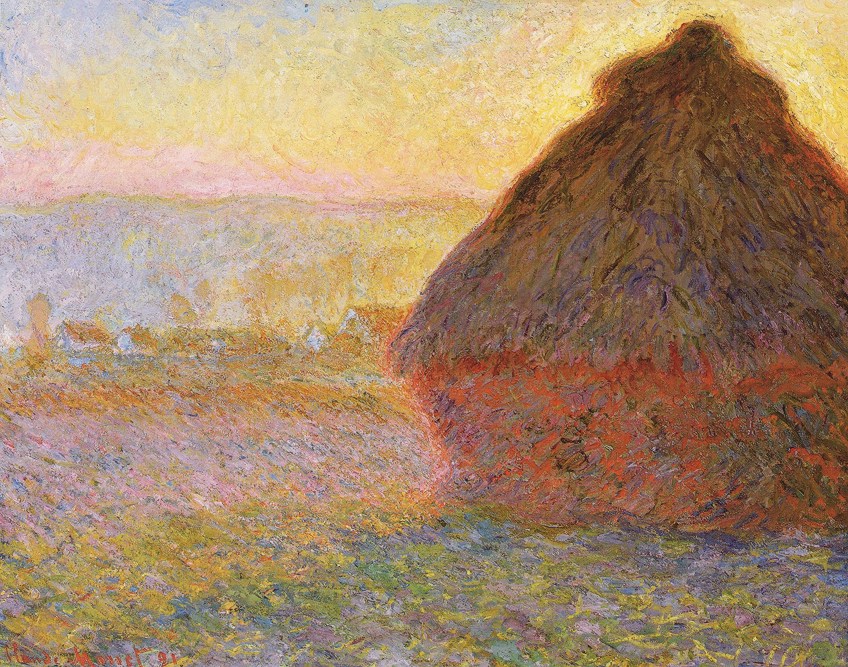

In the formal analysis below, we will discuss the painting titled Grainstacks (1890). This painting is housed on permanent loan at the Barberini Art Museum in Potsdam, Germany as part of the Hasso Plattner Collection. We will also make mention of other examples from Monet’s Meules series throughout.

Visual Description: Subject Matter

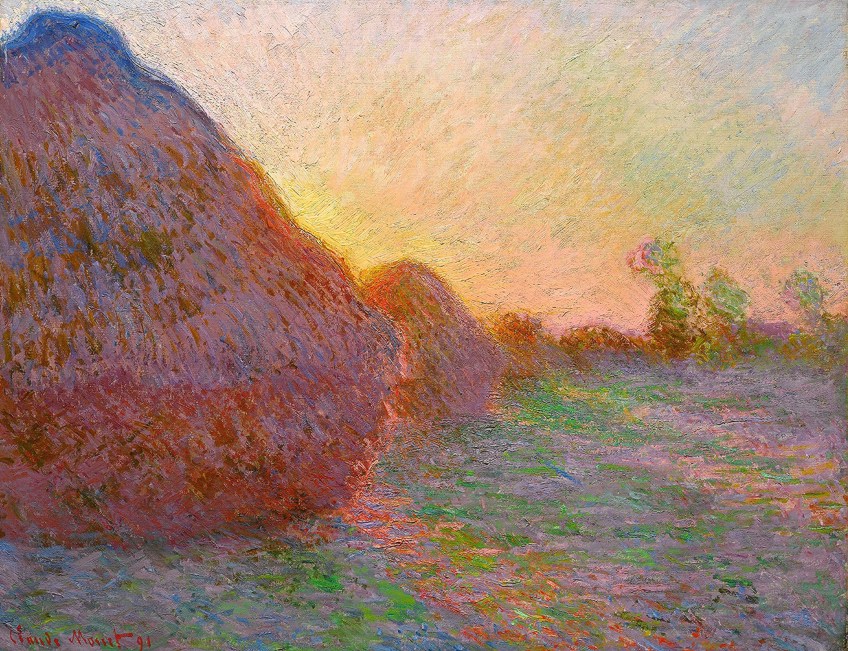

In Grainstacks (1890), the composition can be viewed in threes, namely, the open space of the field in the foreground, which dominates the right side of the composition more. In the middleground, there are several grain stacks, the biggest of which starts in the left foreground with smaller, receding stacks behind it, delineating the middleground.

The stack creates a line along the center of the composition.

This line seemingly separates the land on the lower portion of the canvas from the sky on the upper portion of the canvas. The sky takes up a large portion of the background. Additionally, to the right edge in the center of the composition, there appear to be three trees forming part of the landscape.

We see what appears to be the setting sun, making way for the early evening, behind the stacks. The sun is not directly indicated, but only deduced from its radiant yellow glow. This is a backlighting effect, common in photography.

This is referred to as the French term “contre-jour”, which means “against daylight” in English.

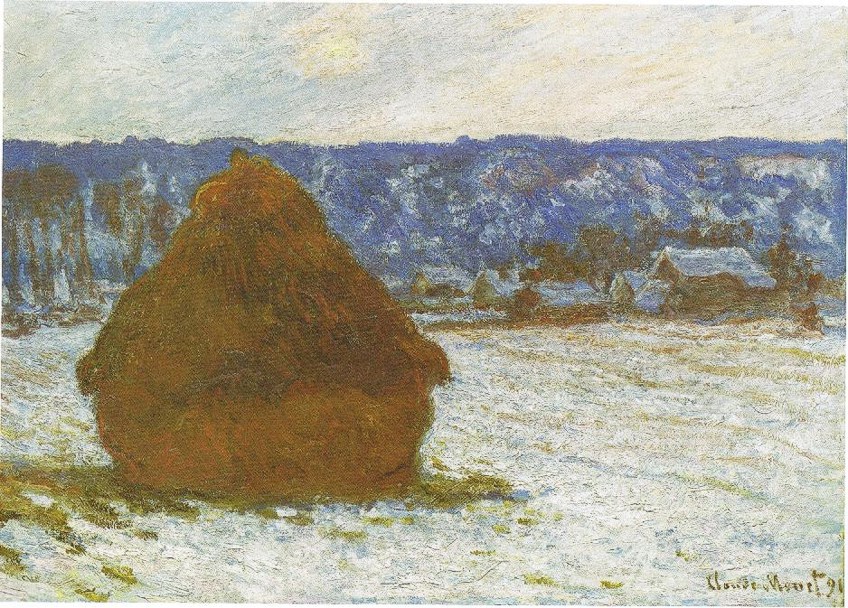

In other examples from Monet’s Meules series, we will see other aspects of the landscape too, for example, Wheatstack (Snow Effect, Overcast Day) (1890-1891), which is housed at the Art Institute of Chicago in the United States. In this painting, the background depicts a grayed hillside/mountainous region with several houses to the right.

Here, we can also vaguely view the orb of the sun behind the overcast sky, placed slightly off-center. Monet also depicted just one stack of wheat.

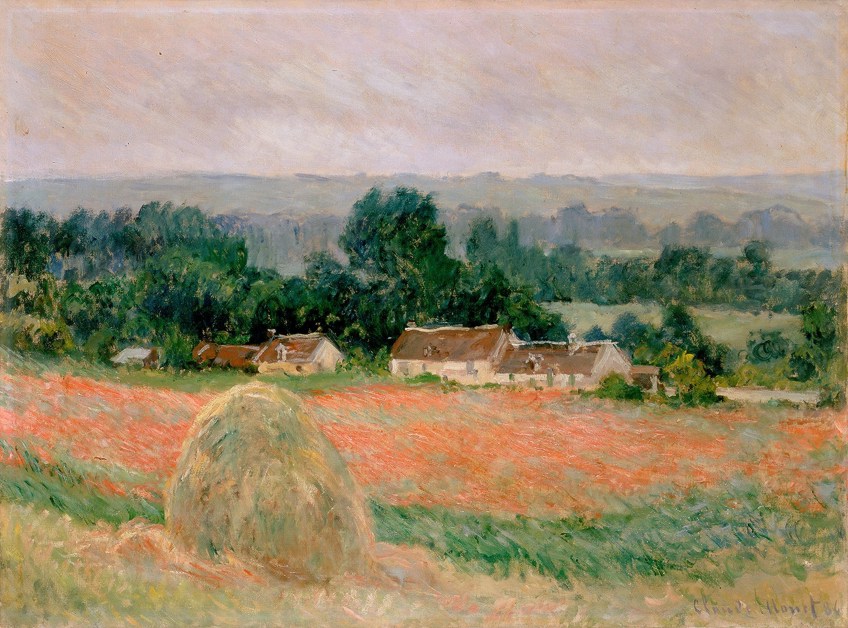

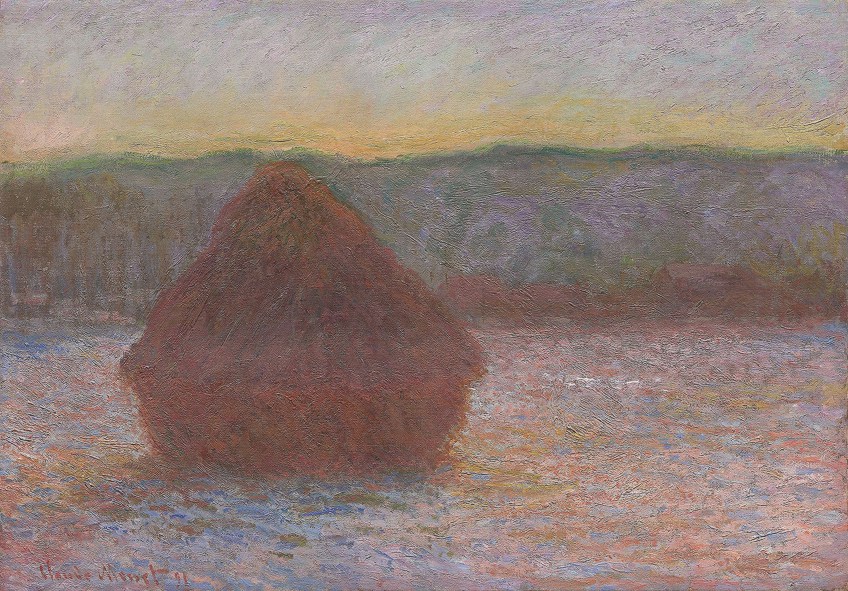

In Stack of Wheat (Thaw, Sunset) (1890-1891), also housed at the Art Institute of Chicago, Monet depicted a hillside in the background with a row of trees in the middleground to the left and what appears to be shapes of houses to the right. The sunset blankets the top of the hillside with a glistening glow.

Like the composition mentioned above, there is only one stack depicted.

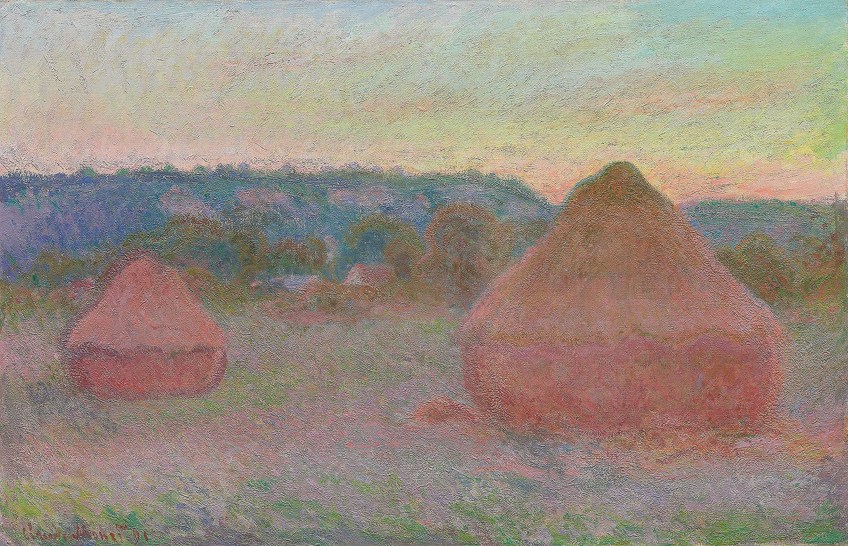

In Stacks of Wheat (End of Day, Autumn) (1890-1891), Monet placed two stacks, one to the right in the foreground and one to the left that is slightly receded. Here, we see another hillside that appears more undulating and topped with the greenery from foliage and trees.

There appear to be more trees and a forested area just in front of the hillside in the middleground, and we can also see what looks like two houses. The sunset is subtler in this rendering, and it appears darker with the onset of evening.

In the lower-left corner, Monet signed his name in red as “Claude Monet 91”. We will see this signature in most of his other paintings from this series.

Color and Light

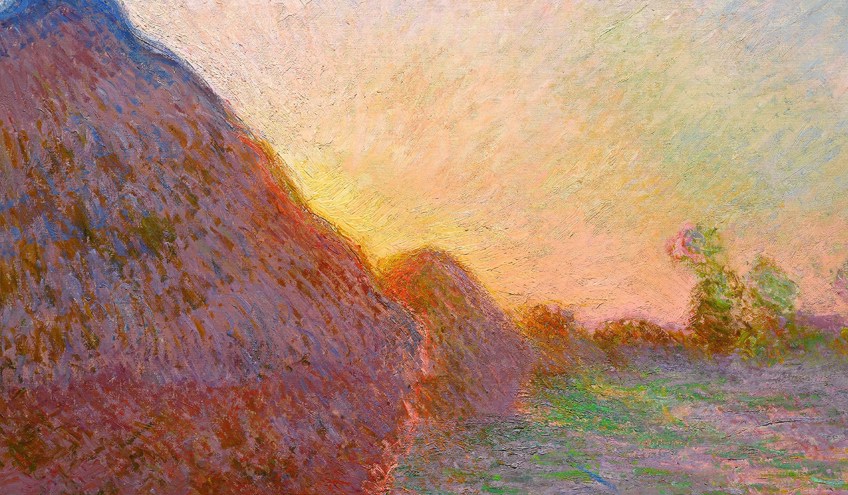

If we return to looking at Grainstacks (1890) from the Hasso Plattner Collection, Claude Monet utilized a bright color palette, giving the composition an almost lighthearted mood or ambiance. Monet applied different hues of pinks, violets, reds, greens, blues, whites, and more, all of which complement each other, creating a harmonious composition.

In the upper portion of the composition, we see the golden yellow glow from the sun lighting up the sky. This yellow is especially emphasized as it finds its way between the two larger grainstacks in the forefront.

Here, we will see how Monet applied a thicker outline of a mustard-yellow along the contoured edges to highlight the sun.

Furthermore, as we move along the middleground, Monet applied darker tones of greens and yellows against what appears to be a backdrop of lighter violets and pinks. These darker tones create the effect of implied shadows as the sun’s light shines on the trees and stacks. Similarly, the colors in the foreground are darker, denoting the shaded area. In the foreground, we see more reds, blues, and violets.

The reds are on the large grainstack in the forefront and its top tip has a distinct bluish hue, indicating the shadow created by the sunshine.

Texture

If we look closely, we can see Monet’s brushstrokes as he worked on the Grainstacks composition. In some areas like the sky, particularly in the top-right corner, the paint appears thinner in application compared to the thicker impasto towards the left, where the larger grainstack meets the sky.

Here, it appears as if Monet hastily applied the paint with shorter brushstrokes.

There are more elongated brushstrokes along the contours of the grainstacks to the left, which create an implied texture here of how the hay covers the grain/wheat. As we move more to the right, towards the distance in the middleground, Monet’s brushstrokes appear more haphazard in their application.

This creates a blurring effect, denoting the distant foliage and trees that would not be in clear view.

Line, Form, and Shape

In this rendition of Monet’s Meules series, there are horizontal and diagonal lines formed by the way the artist arranged the stacks. Starting from the left foreground, they recede towards the right in the center of the composition.

This creates a curved line along the middleground, as if dividing the upper and lower portions.

This line, as well as the repetition of the receding stacks, creates a sense of rhythm and balance. The primary shapes and forms we see in this composition are triangular and conical in the form of the stacks, especially the looming stack to the left.

Space and Scale

The measurements of Grainstacks are around 73 x 92.5 centimeters. Reportedly, Monet utilized the same four canvas sizes throughout his Meules series. The above size, also referred to as “standard-size no. 30 figure format”, was for the depiction of stacks viewed from a closer perspective.

This can be seen in the large stack in the left foreground, which almost enters our space and is partly cut off as it meets the edge of the canvas.

Other examples of this size include Grainstack (Sunset) (1891), which is housed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusetts in the United States of America. In this depiction, the large stack is to the right of the composition, and it is also slightly cut off at the canvas’ edge.

This creates a sense of realism, as if we are viewing a fleeting moment in time.

Honing in the Harvest

When the series was exhibited in 1891 by the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, it left a positive impression on many and several paintings were sold. The above-mentioned Grainstacks painting was sold for $110.7 million at an auction in 2019, although Bertha Honoré Palmer initially purchased it in 1892.

Monet’s Meules series can now be found at various institutes around the world. As we have seen in the article above, some are held in various cities in the United States, while others are in Europe like Paris, as well as in Tokyo, Japan.

Claude Monet’s “Wheatstacks” series is a true testament to an artist who rendered the surrounding landscape and its dazzling atmospheric effects with great compositional acuity. Not only did he celebrate the beauty of the landscape through colors and light, but he also honed in on the French countryside and what it possibly symbolized for many, which was harmony, the land, and life.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Painted the Famous Haystacks Series?

The Impressionist and famous haystacks painter, Claude Monet, created the Haystacks (1890-1891) series, also termed Meules in French, referring to a stack in English. There are around 25 paintings in this series depicting wheatstacks in the countryside.

Where Did Claude Monet Paint the Wheatstacks Series?

Claude Monet painted his famous series of Impressionist paintings of stacks of wheat, titled Wheatstacks (1890-1891), also commonly referred to as his Haystacks series, when he lived in Giverny in France. He reportedly saw the large stacks of wheat on his neighbor’s farm.

Why Did Claude Monet Paint So Many Haystacks?

Claude Monet painted over 20 renditions of wheatstacks/grainstacks, which were covered in hay and often erroneously called haystacks. He wanted to depict the effect of light through color on the wheatstacks/grainstacks throughout different seasonal changes like autumn and winter and weather changes like sunrise, sunset, frost, and fog.

Alicia du Plessis is a multidisciplinary writer. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Classical Civilization, as well as two Honors, namely, in Art History and Education and Development, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. For her main Honors project in Art History, she explored perceptions of the San Bushmen’s identity and the concept of the “Other”. She has also looked at the use of photography in art and how it has been used to portray people’s lives.

Alicia’s other areas of interest in Art History include the process of writing about Art History and how to analyze paintings. Some of her favorite art movements include Impressionism and German Expressionism. She is yet to complete her Masters in Art History (she would like to do this abroad in Europe) having given it some time to first develop more professional experience with the interest to one day lecture it too.

Alicia has been working for artincontext.com since 2021 as an author and art history expert. She has specialized in painting analysis and is covering most of our painting analysis.

Learn more about Alicia du Plessis and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Alicia, du Plessis, ““Haystacks” by Claude Monet – Monet’s Grainstacks at Giverny Paintings.” Art in Context. June 7, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/haystacks-by-claude-monet/

du Plessis, A. (2022, 7 June). “Haystacks” by Claude Monet – Monet’s Grainstacks at Giverny Paintings. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/haystacks-by-claude-monet/

du Plessis, Alicia. ““Haystacks” by Claude Monet – Monet’s Grainstacks at Giverny Paintings.” Art in Context, June 7, 2022. https://artincontext.org/haystacks-by-claude-monet/.