Hellenistic Art – Ancient Greek Multiculturalism

In both art and history, the Hellenistic era pertains to the period of Alexander the Great’s conquests and the following expansion of Greek civilization throughout the great cities and countries of the Mediterranean, Southern Europe, and the Near East. Hellenistic art is primarily represented via sculpture, which had been more effectively depicted in precision, physiology, emotion, and motion than the classical forefathers’ sculptures. What is a Hellenist, though? The Hellenists worked hard to promote ancient Greek tradition to the people they invaded and to demonstrate the supremacy of their civilization.

Table of Contents

Hellenistic Greek Art History

When Alexander led the Greeks to triumph, he split the captured regions among his commanders, the Diadochi. The Near Eastern Seleucids, the Egyptian Ptolemies, and the Macedonian Antigonids were all born in these countries. Other lands formed leagues, such as the Achaean and Aetolian Leagues.

These kingdoms and alliances eventually disintegrated into smaller kingdoms enriched with Greek cultural characteristics.

Hellenistic Culture

Grecian influences combined with native culture during these kingdoms resulted in a wide range of techniques and subjects in Hellenistic art. The historical curiosity that defined this era was also a significant influence on the value of the art generated. The libraries of Pergamon and Alexandria provided artists with accessibility to this heritage, which, along with their understanding of previous artworks, provided them with a basis from which to work with invention and inventiveness.

As local faiths grew more secularized as a result of Grecian influence, and as those religions affected Greece, artists discovered new methods to represent their own gods. Eros, for instance, is shown as a young boy, whereas Aphrodite is depicted naked. The presence of the elderly and children, individuals of various races (especially Africans), and grotesque sculptures demonstrate that diversity was not restricted to religious vs. secular influence.

Because not every figure was an Olympian, deity, or orator, the artists had to devise a wide range of positions to effectively reflect these new sculptural personalities. With these Hellenistic statues, sculptors sought to build the position on a spiraling twist so that the observer could see something interesting from all angles.

Sometimes these stances appeared to serve a purpose, while other times the reasons appeared to be insignificant or contained within a single motion, such as a satyr inspecting his tail. There are relatively few paintings from Hellenistic culture that have survived.

What has survived are mosaics that are thought to be exact replicas of the original frescoes. Scholars might conclude from these mosaics that Hellenist artists used twisting motion, strongly expressive features, and accurate representations of nature. A landscape artwork in an unfinished collection of pictures from the Odyssey demonstrates that the artwork was created by a talented artist using disciplined brushwork and expertise in light, shadow, and the capability to portray distance in color.

There are also Hellenist Fayum Egyptian Mummy Portraits, which demonstrate how much the Hellenists affected Egyptian art. These portraits depicted living humans, not mummies, with accurate, realistic, and lifelike detail.

They are similar to portrait styles from the mid-19th century. While clay and ceramics were in decline, bronze and goldsmiths of the time excelled at creating vessels, jewelry, and figures with intricate decorative work. Mythical monsters, African people, gods, and wreaths were among the subjects. Many of the metalwork objects were set with expensive stones and jewels.

Glass blowing was discovered by the Hellenists, who were able to develop new kinds of art. The molded glass was used to make jewelry in Italy, and jewelers devised and improved the cameo.

Hellenistic Statues and Sculptures

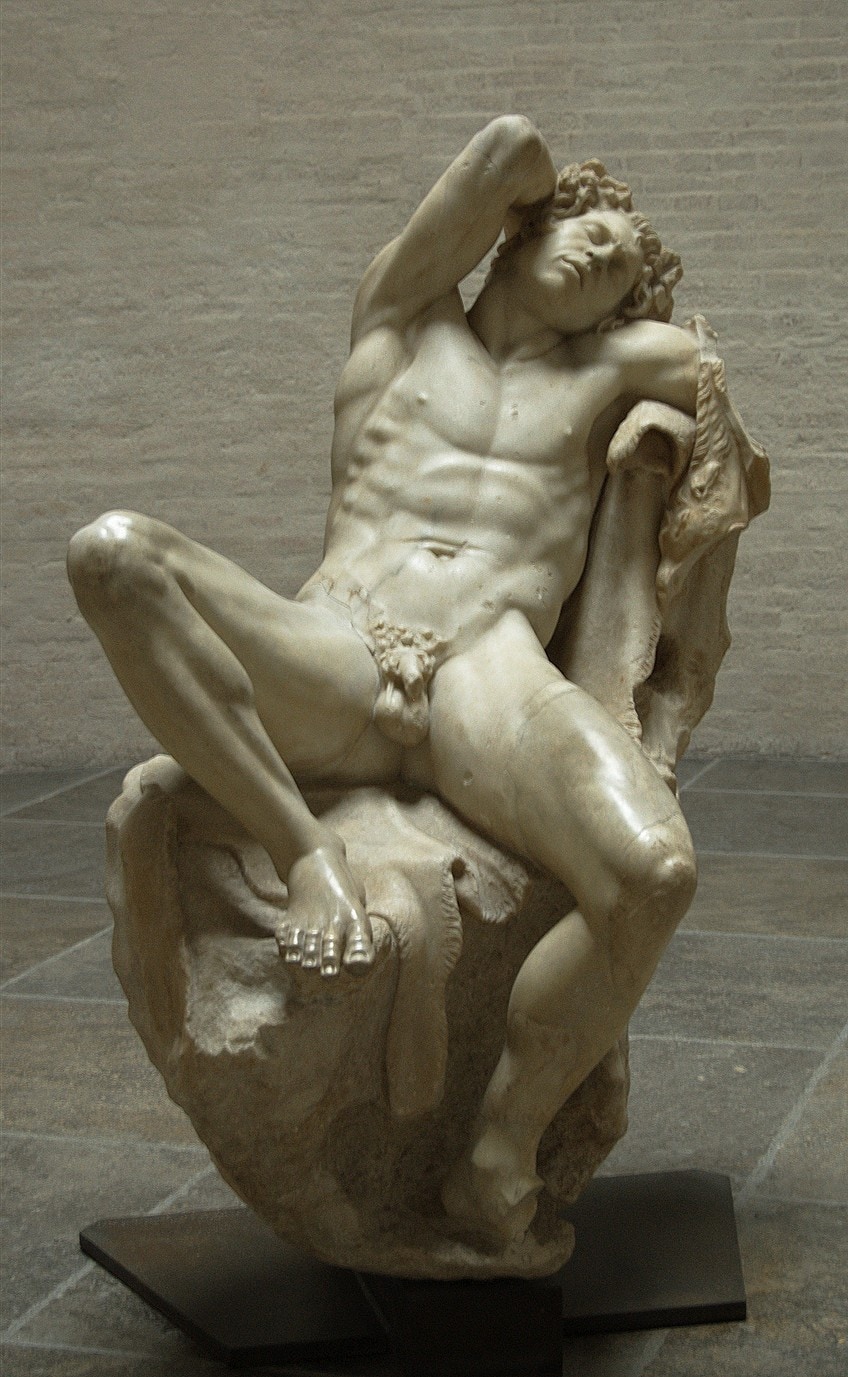

After 293 BC, sculpting fell considerably. After that, there was a period of stasis, with a relatively short reemergence after 153 BC, but nothing up to the quality benchmark of the periods before it. Sculpture grew increasingly lifelike and expressive throughout this period, with an emphasis on conveying extremes of expression. Aside from physical accuracy, the Hellenistic sculptor strives to depict the personality of his subject, encompassing subjects such as anguish, sleep, and old age.

Ordinary folk, mothers, children, animal life, and household scenes became appropriate subjects for Hellenistic statues, which were funded by wealthy families to decorate their residences and gardens. A notable instance is “A Boy with Thorn” (101 AD).

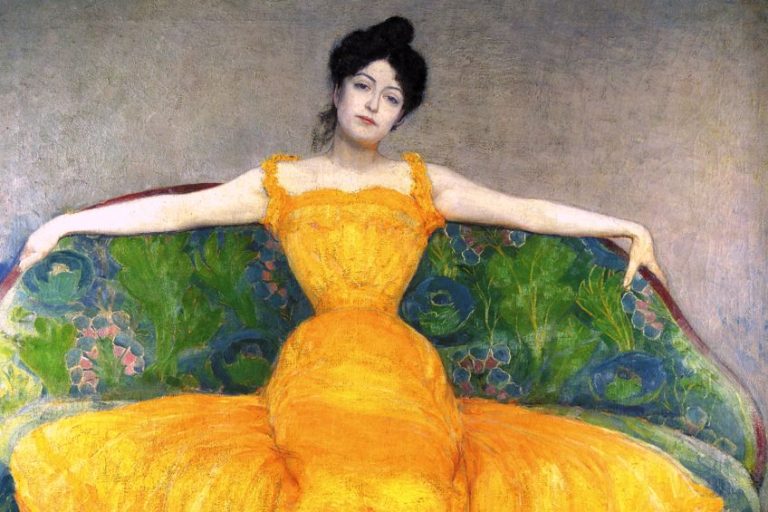

Artists no longer felt obligated to show individuals as standards of beauty or bodily perfection, and accurate representations of women and men were created. Dionysus’ realm, a pastoral utopia filled with satyrs and nymphs, had been shown frequently in previous vase paintings and figures, but seldom in full-size sculptures. The Old Drunkard (first century AD) in Munich depicts an elderly lady, gaunt and haggard, clutching a jar of alcohol against herself.

Portraits

As a result, the era is noteworthy for its portraiture. The Barberini Faun (1799) of Munich, for example, depicts a sleeping satyr with a comfortable posture and a worried expression, maybe the prey of dreams. Similar themes are reflected in the Resting Satyr, The Belvedere Torso (1430), and The Sleeping Hermaphroditus (1620).

“Demosthenes” (384–322 BC) by Polyeuktos is yet another well-known Hellenistic portrait that depicts him with a well-executed face and clenched fists.

Privatization

Another Hellenistic-era tendency may be noticed in its art: privatization, as demonstrated in the reintroduction of previous public patterns in ornamental sculpture. Under the influences of Roman art, portraiture is tinted with realism. New Hellenistic cities sprung up throughout Egypt, Syria, and Anatolia.

This necessitated the installation of sculptures representing Greek deities and characters in sanctuaries and public spaces. Sculpture, like ceramics, became a business as a result, with uniformity and some degradation of quality.

As a result of these factors, considerably more Hellenistic statues have endured than Classic sculptures.

Second Classicism

The developments of “second classicism” are repeated in Hellenistic statues. This comprises naked sculpture-in-the-round, which allows the sculpture to be appreciated from all sides; drapery and the illusions of transparency of clothes, as well as the flexibility of positions.

As a result, “Venus de Milo” (between 150 and 125 BC), despite emulating a traditional figure, is differentiated by the curve of her hips.

Baroque

The group of statues that featured multiple figures was a Hellenistic invention, most likely from the third century, that removed the epic conflicts of older sanctuary reliefs off their walls and created them as life-size sculptures.

Their style is commonly referred to as “baroque,” due to their extravagantly deformed body positions and dramatic emotions on their faces. “The Laocoön Group” (1506), which is discussed further below, is regarded as a classic instance of the Hellenistic baroque era.

Pergamon

Pergamon did not identify itself just via its architecture. It was also the home of the famous Pergamene Baroque style of sculpture. Mimicking previous eras, the sculptors depict traumatic situations rendered emotive using three-dimensional designs, and physiological hyper-realism.

One instance is the “Barberini Faun” (1799).

Gauls

To memorialize his triumph against the Gauls, Attalus I crafted two series of groups: the first, anointed on the Acropolis of Pergamon, contains the famed Gaul massacring himself and his wife, the second, given to Athens, is made up of small statues of Amazons, divine beings and giants.

The Louvre’s “Artemis Rospigliosi” (1st – 2nd centuries AD) is most likely a replica of one of them.

This is because copies of the Dying Gaul were plentiful during the Roman period. The Pergamene style is characterized by the portrayal of emotions, the boldness of details, and the aggressiveness of movements.

Great Altar

These features are shown in the friezes of Pergamon’s Great Altar (2nd century BC), which was adorned under the direction of Eumenes II with a gigantomachy reaching 110 meters in length, portraying stone poetry written specifically for the court.

It is won by the Olympians, each on his own side, over Giants, most of whom are changed into terrible monsters such as snakes, birds of prey, lions, or cows. Gaia rushes to their assistance, but she is powerless to help and must watch as they squirm in agony under the gods’ blows.

Colossus of Rhodes

Rhodes was one of the few city-states that managed to remain completely independent of any Hellenistic power. After surviving a year-long siege the Rhodians erected the Colossus of Rhodes (280 BC) to celebrate their triumph.

The Greeks were able to construct huge sculptures because of advancements in bronze casting. Many of the huge bronze statues were destroyed, with the vast number being melted down to reclaim the material.

Laocoön

Discovered in Rome in 1506 and instantly noticed by Michelangelo, it began to have a tremendous effect on Renaissance and Baroque artwork. Laocoön, choked by serpents, struggles hard to break free without looking at his dead sons.

The grouping is one of the few non-architectural antique sculptures that may be linked to those recorded in ancient texts.

Rococo

The Baroque characteristics of Hellenistic art, particularly sculpture, have been compared with a contemporaneous tendency known as Rococo. Wilhelm Klein invented the term “Hellenistic Rococo” in the early twentieth century.

In contrast to the intense Baroque statues, the Rococo movement stressed lighthearted themes like satyrs and nymphs. The sculptural group, “The Invitation to the Dance”, was a prominent example of the movement.

Lighthearted images of Aphrodite and Eros were also common. Later, it was believed that the desire for “Rococo” themes in Hellenistic statues might be linked to a shift in the usage of sculpture generally. Personal sculpture collecting grew more prevalent in the late Hellenistic era, and there appears to have been a penchant for “Rococo” elements in this kind of collection.

Neo-Attic

Scholars consider the Neo-Attic style of sculpture as a response to baroque extravagance, a reversion to a form of Classical tradition, or a continuance of the usual style for worship statues beginning in the second century.

Studios in the style began to specialize in producing replicas for the Roman market, which favored traditional rather than Hellenistic works.

Mosaics and Paintings of the Hellenistic Era

Paintings and mosaics were major mediums in Hellenistic Greek art. However, no instances of paintings on panels escaped the Roman conquest. Related media and what appear to be replicas of or loose extensions from artworks in a wider range of materials might give some notion of what they were like.

Landscape

The greater use of landscape in Hellenistic mosaics and paintings is perhaps the most remarkable feature. The landscapes in these pieces of art depict recognized realistic characters as well as mythological and Sacro-idyllic motifs.

Landscape friezes were frequently utilized to depict settings from Hellenistic poetry. These settings depicting the tales of Hellenistic authors were used in the house to highlight the family’s awareness and education of the world of literature.

The term “Sacro-idyllic” refers to the artwork’s most prominent aspects, which are those associated with religious and pastoral themes. This style, which first appeared in Hellenistic art, blends holy and profane elements to create a dreamy scene. the Nile Mosaic of Palestrina (1st century BC) exhibits imaginative storytelling with a color scheme and everyday components that portray the Nile in its transit from the Mediterranean to Ethiopia.

Hellenistic backdrops can also be found in works from Pompeii, Cyrene, and Alexandria.

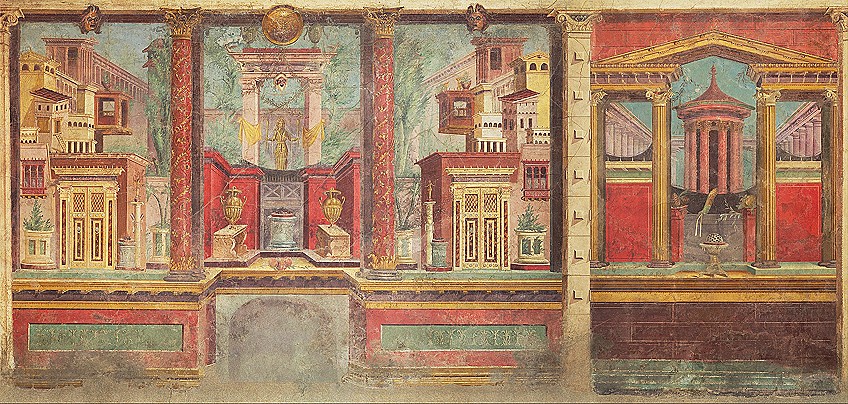

Furthermore, floral motifs and limbs can be observed on ceilings and walls strewn in a disorganized yet traditional fashion, imitating a late Greek style, particularly in Southern Russia. Furthermore, “Cubiculum” paintings unearthed at Villa Boscoreale show greenery and a rocky landscape in the background of realistic paintings of big structures.

Wall Paintings

During the Pompeian period, wall paintings became more prevalent. These wall murals were not just featured in temples or tombs. Wall paintings were frequently utilized to beautify the dwelling. In Priene, Thera, Olbia, Pantikapaion, and Alexandria, wall paintings were widespread in private residences.

Only a few specimens of Greek wall murals have survived the ages. The ones in the Macedonian imperial graves at Vergina are the most spectacular in terms of demonstrating what high-quality Greek artwork looked like.

Greek artists are credited with introducing key representations to the Western hemisphere through their artwork. Three-dimensional viewpoint, the utilization of lights and shadows to convey form, and Trompe-l’oeil reality were three key characteristics of the Hellenistic style of painting. Except for wooden panels and those put on stone, very few examples of paintings exist in Hellenistic culture.

The most well-known stone paintings may be found in the Macedonian Tomb at Agios Athanasios.

Techniques and Mediums

Recent Mediterranean digs have shown the technologies utilized in Hellenistic painting. The secco and fresco methods were used in wall art during this period. The fresco technique needed layers of lime-rich plaster to be applied to surfaces and stone foundations before they could be decorated.

The secco method, on the other hand, did not require a base and instead employed gum arabic and egg tempera to create finalizing features on marble or other stone. The Masonry friezes on Delos are an example of this technique.

Both techniques made use of locally available materials, manufactured artificial pigments, and organic materials as colorants.

Modern Discoveries

Recent finds include chamber tombs at Vergina (1987), in the old kingdom of Macedonia, where several friezes were discovered. Archaeologists discovered a Hellenistic-style frieze portraying a lion hunt in Tomb II, for instance. This frieze discovered in a tomb reportedly belonging to Philip II is notable for its structure, the placement of the characters in space, and its accurate depiction of nature.

Other friezes, such as a symposium and feast or a military procession, preserve a realistic storyline and may repeat actual events.

There are also the newly repaired Nabataean frescoes from the 1st century in Jordan’s Painted House. Because the Nabataeans interacted with the Egyptians, Romans, and Greeks, the insects and other creatures depicted in the murals represent Hellenism, while different varieties of vines are linked with the Greek god Dionysus. The latest archaeological findings at the Pagasae cemetery, on the outskirts of the Pagasetic Gulf, have revealed several unique works.

The excavated works may be linked to numerous Greek artists from the third and fourth centuries, who represent events from Alexander the Great’s reign. A collection of wall paintings was discovered in Delos in the 1960s.

The remains of friezes discovered were clearly constructed by a colony of painters who existed during the late Hellenistic era. The paintings emphasized household decorating, implying that the Delian regime will stay strong and stable enough for this work to be appreciated by residents for many coming years.

Mosaics

Certain mosaics give an excellent understanding of the period’s “great painting.” These mosaics are reproductions of frescoes that have been lost to the ravages of time. This art form has mostly been utilized to embellish walls, floors, and columns.

Techniques and Mediums

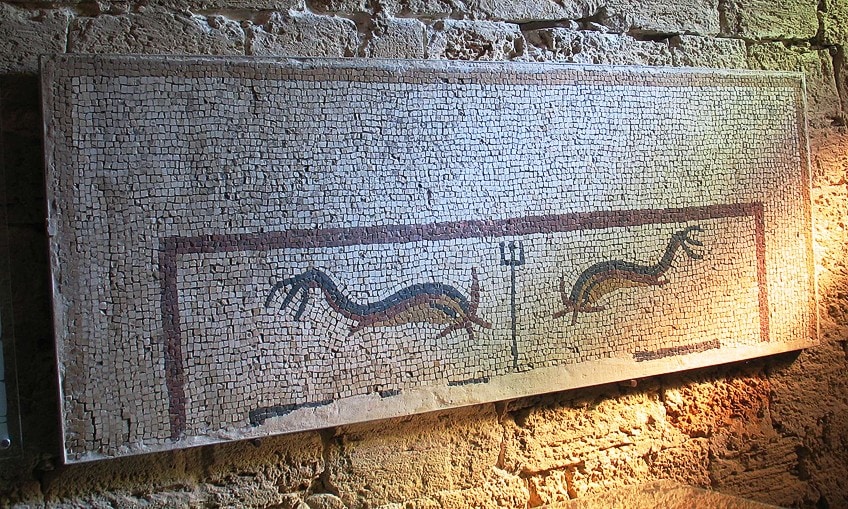

The evolution of mosaic artwork during the Hellenistic Era started with Pebble Mosaics, which are best depicted in the 5th century BC at the site of Olynthos. Pebble Mosaics were created by arranging tiny black and white pebbles of varying sizes in a rectangular or circular panel to depict images from mythology.

To produce the image, white pebbles in slightly various colors were put on a blue or black backdrop. The black stones were used to frame the imagery.

A highly advanced form of art may be seen in the mosaics from the 4th century BC site of Pella. This site’s mosaics show the usage of stones that have been tinted in a wider spectrum of hues and tones. They also demonstrate the early use of lead wire and Terra-cotta to generate more defined curves and features in the mosaic pictures. More materials were eventually added after this scenario. Precisely cut pebbles, broken stones, glass, and baked ceramic, known as tesserae, are examples of this increased usage of elements in mosaics from the third century BC.

This enhanced the mosaic method by allowing artists to create more clarity, considerable detail, a finer fit, and a larger spectrum of colors and hues. Regardless of the chronological order in which these methods appeared, there is no data to imply that the tessellated evolved from pebble mosaics. The vast bulk of mosaics was created and installed on-site.

A few floor mosaics, however, employ the “emblemata” process, in which picture panels are manufactured off-site in trays of terra-cotta or stone. These trays were then placed on-site in the setting bed.

Colored grouts were employed on opus vermiculatum mosaics in Delos, although this is not prevalent in other places. The Dog and Askos mosaic in Alexandria is one example of colorful grout being utilized. The grouts and tesserae on Samos are both colored. Scientific study has provided valuable information on the grouts and tesserae in use in Hellenistic mosaics. As a distinguishing feature of the surface treatment, lead strips were detected on mosaics.

The mosaics here are devoid of lead strips. Lead strips were popular on mosaics in the opus tessellated style at Delos. These strips were used to delineate ornamental borders as well as geometric decorative elements. The strips were especially popular in Alexandria opus vermiculatum mosaics. Because lead strips were present in both types of surfaces, they cannot be the primary distinguishing feature of one or the other.

Tel Dor Mosaic

An uncommon virtuoso Hellenistic type image mosaic was discovered on the Levantine shore. Researchers believe that this mosaic was made in situ by itinerant craftsmen based on a technical investigation of the mosaic.

Over 200 shards of the mosaic have been unearthed at Tel Dor’s headline since 2000, but the demolition of the original mosaic is unclear. Excavators believe the reason is an earthquake or urban redevelopment.

Although the original architectural context is unclear, stylistic and technical parallels point to a late Hellenistic period date, possibly at the end of second-century B.C.E. Scholars discovered that the original mosaic included a centered rectangle with unknown iconography, flanked by a succession of artistic borders consisting of a perspective meandering. It was also accompanied by a mask-and-garland border after analyzing the shards recovered at the original location.

Alexander Mosaic

Another example is the Alexander Mosaic (100 BC), which depicts the young victor and Grand King Darius III clashing during battle and is an artwork from a floor in Pompeii’s House of the Faun. It is thought to be a replica of a picture mentioned by Pliny as having been created by Philoxenus of Eretria for King Cassander of Macedon towards the end of the fourth century BC, or perhaps of a work by Apelles contemporary with Alexander.

The mosaic allows us to evaluate the color palette as well as the ensemble’s composition through turning motion and facial expressions.

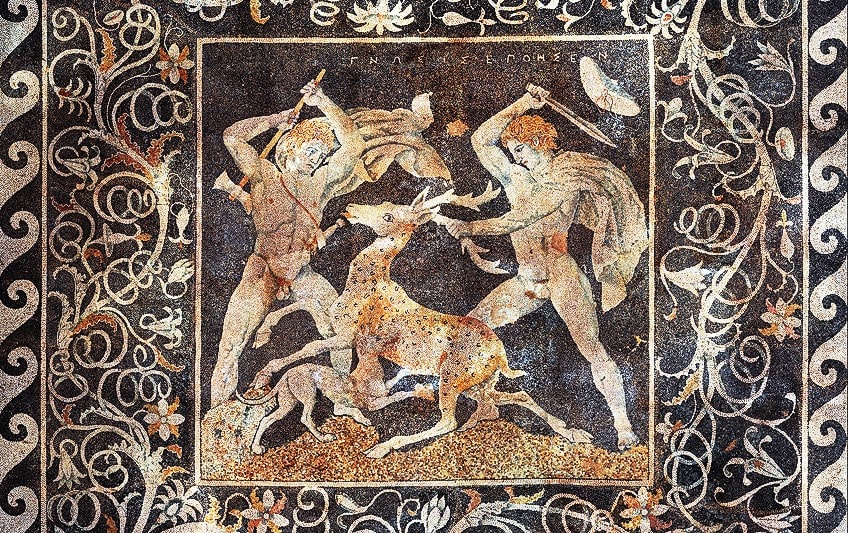

Stag Hunt Mosaic (300 BC)

The emblem is surrounded by an exquisite floral design that is surrounded by stylized portrayals of waves. The work is a pebble mosaic composed of stones gathered from coastlines and riverbanks and placed in cement. The mosaic, as was maybe often the case, represents painting techniques. The bright figures against the darker backdrop might be a reference to a red-figure painting. The mosaic also employs shading, in its portrayals of the individuals’ muscles and capes.

The artwork is three-dimensional as a result of this, as well as the use of overlapping figures to create depth.

Sosos

The Hellenistic era is also a period of mosaic development, notably with the creations of Sosos of Pergamon, who was prominent in the 2nd century BC. His interest in optical illusion and the impacts of the medium can be seen in several creations ascribed to him, including the Unswept Floor in the Vatican Museum, which depicts the leftovers of a meal, and the Dove Basin at the Capitoline Museum, which is known thanks to a reproduction discovered in Hadrian’s Villa.

That concludes our look into Hellenistic Greek art. The Hellenistic era spanned 300 years and was marked by inventions, globalization, and cultural connection via a shared language and standardized schooling. Royal families lived in magnificence and prosperity throughout the Hellenistic period. Palaces feature opulent dining halls, ornately adorned chambers, and magnificent gardens. Extensive wealth encircled the stately homes and the palaces of the aristocracy, political elite, and merchants, who hosted celebrations and symposia to showcase their riches on a regular basis. A rich society with famous patrons of the arts who commissioned public projects of sculpture as well as private luxuries to demonstrate their money and social standing.

Take a look at our Hellenistic period art webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is a Hellenist?

You might be wondering what exactly a Hellenist is. A Hellenist is an individual who lived during the Hellenistic period and was Greek in dialect, viewpoint, and mode of living but was not necessarily Greek in lineage. The Hellenists worked for years to promote ancient Greek tradition to the people they conquered and to demonstrate their civilization’s superiority.

What Is the Hellenism Definition?

You might be wondering what the Hellenism definition is. The Hellenistic period began with the demise of Alexander the Great in 323 BC. During this period, art began to depart from traditional classical principles, with painters of the time injecting their pieces with fresh stylistic choices. Jewelry got more ornate, sculptures became more expressive (almost theatrical), and buildings defied convention by growing larger. During these kingdoms, Grecian influences coupled with native culture resulted in a diverse range of styles and topics in Hellenistic art. The historical interest that marked this age had a tremendous impact on the value of the art that resulted. Hellenistic art depicted individuals of different ages, from infants to the elderly.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Hellenistic Art – Ancient Greek Multiculturalism.” Art in Context. April 13, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/hellenistic-art/

Meyer, I. (2022, 13 April). Hellenistic Art – Ancient Greek Multiculturalism. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/hellenistic-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Hellenistic Art – Ancient Greek Multiculturalism.” Art in Context, April 13, 2022. https://artincontext.org/hellenistic-art/.