Mesopotamian Art – Exploring the Architecture and Art of Mesopotamia

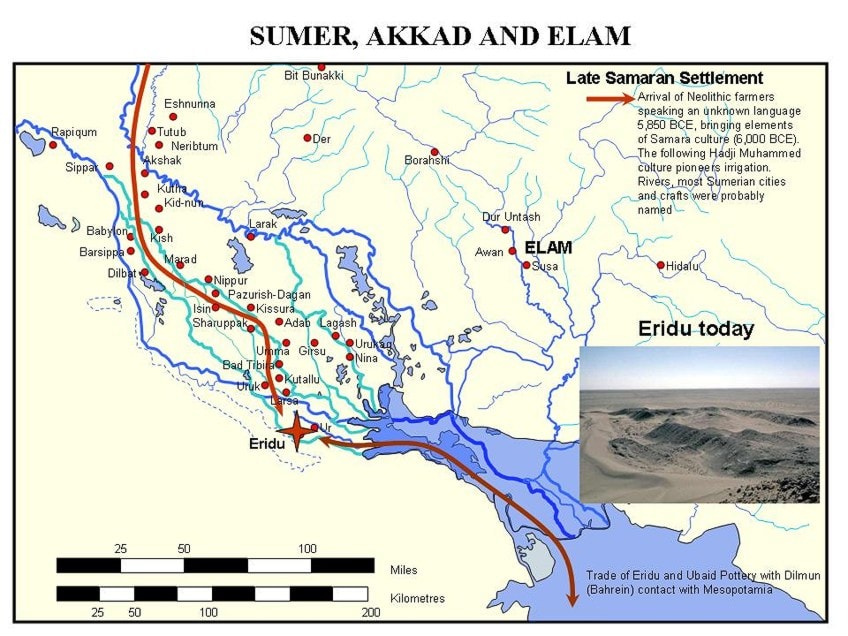

Mesopotamia is a name that refers to the region in Western Asia that spanned over the area of modern-day Iraq, Turkey, Iran, and Syria. Mesopotamia is often referred to as the birthplace of civilization, as the first records of written history can be traced back to this region. Mesopotamian artifacts from the days of the hunter-gatherers still exist, as well as examples of the ancient Mesopotamian arts from the Bronze Age and through the various Empires. Let us take a deeper look at the history and art of Mesopotamia.

Table of Contents

The Early Cultures of Mesopotamian Art

The region now known as Iraq was once called Sumer during the Early Bronze Age. Despite the earliest recorded historical events only dating back to around 2900 BCE, scholars today think that Sumer was first inhabited by people called the Ubaidians sometime between 4500 and 4000 BCE.

IThey were the first to be involved in the industrious creation of masonry, metalworks, leatherwork, and weaving, the first to develop trade, and the first to drain portions of marshland for agricultural use.

Bordering along the Persian Gulf was the city of Eridu, regarded as the first city in the world. It was home to three cultures that became integrated due to their shared geographical position – the fishermen, the Semitic speaking nomadic shepherds, and the Ubaidian farmers. These three groups were all specialists in food production which eventually led to a surplus of food that could be stored.

Unlike hunter-gatherers, this ability to produce and store food meant that instead of constantly migrating in search of resources, people could settle in one place. With the surplus of food came an increase in the population, which in turn required a labor force that could produce goods, services, crafts, and art for the inhabitants.

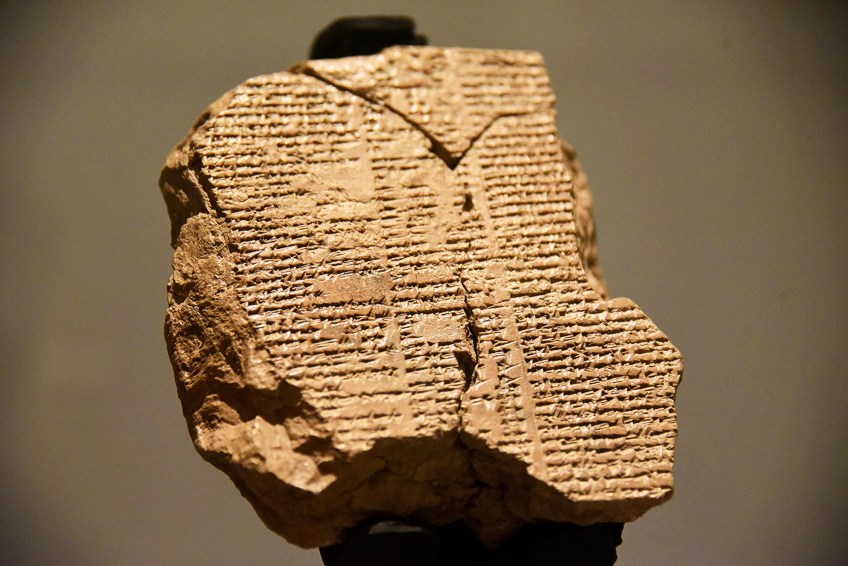

During the early Sumerian period, an early type of written language called cuneiform was developed.

From this language, as well as other ancient Mesopotamian artifacts such as pictograms, we can deduct that there was an abundance of Mesopotamian art traditions. Clay was used for producing pottery and tablets for creating documents, using the sedge-shaped written language they had developed.

Metal was used to create daggers, and gold and copper could be hammered and were used for decorative collars, necklaces, and plates.

The region grew to a point that it was divided by the rivers, canals, and other geographical boundaries into many independent cities. Each of these cities had a temple that was created in honor of their various deities, and each temple had a holy governor who was connected to the religious ceremonies of the city.

The Ubaid Period

The art of Mesopotamia from this period is recognizable by the distinctive painting technique applied to the pottery. These zig-zag and circular patterns were created in a domestic capacity on a slow wheel. It would eventually become a popular style throughout the region. It was during this early period that farmers first established a settlement to attend to their agricultural practices.

Although eventually bypassed in size by the nearby city of Ur, it remained an influential center for religious matters.

The Uruk Period

During this period of transition toward the Uruk period from the Ubaid period, the focus shifted from domestic slow wheels to works that were created large-scale on fast wheels by groups of specialist artists and were unpainted. During this period of economic growth in the region, many new cities began to be developed along the prosperous trade routes of the rivers and canals.

Each of these cities had governing bodies that employed people to take on specialized roles.

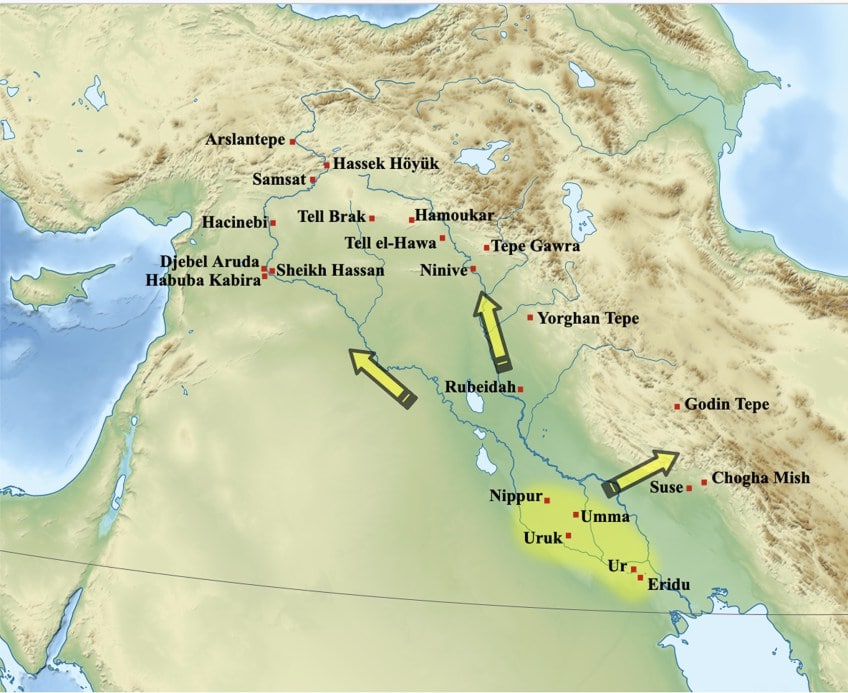

Mesopotamian artifacts of the Uruk period have been discovered over a large range of land – from Central Iran to the Mediterranean Sea and all the way to the Taurus Mountains of Turkey. The Uruk culture had a great influence on surrounding areas due to its spread via the traders of Sumer, who eventually began developing their own cultures and economies that would compete with the Sumerians.

During this period cities were mostly theocratic, meaning they believed a deity ruled over all of society and that a priest was god’s representative of earthly matters.

These holy rulers would also call on a council of male and female elders for assistance. This political model would go on to influence the pantheon of gods structure of the later Sumerian period. This was a period of peace, with no walls around the cities, indicating a lack of need for defense, and there were no soldiers or institutionalized violence.

After surpassing 50,000 inhabitants, Uruk was soon considered the most modernly urbanized of its time in the entire world.

Gilgamesh

Enmebaragesi of Kish is the first recorded king of this region and was mentioned in the Epic of Gilgamesh from around 2100 BCE, leading some scholars to suggest that Gilgamesh might once have been a king of Uruk himself. As depicted in the Epic of Gilgamesh, this period was marred by violence, leading to many undefended villages disappearing and cities becoming increasingly more walled in.

Ceramics in Mesopotamian Art

Ancient Mesopotamian arts such as ceramics began to see shifts in variety and styles in the fourth millennium BCE due to certain technological advancements such as the potter’s wheel. The production of ceramics first came out of East Asia sometime between 20, 000 and 10,000 BCE, but making clay by throwing it on a potter’s wheel was a practice that originated in Mesopotamia in the fourth millennium BCE.

The oldest examples of clay vessels date back to the Copper or Chalcolithic Era, divided into the periods discussed above, the Ubaid and Uruk periods.

The Chalcolithic Era

The pottery produced during the Ubaid period was made on slow wheels at home and was highly decorated. Mesopotamian artists created jars, bowls, and vases with fired clay and painted decorative and abstract designs – a style that spread throughout the region. Ceramics in the following period were produced with much greater ease and at greater volume thanks to the invention of the potter’s wheel.

The Akkadian Empire

During the period of Akkadian take over of Sumerian cities, artists continued to create vases, jars, bowls, and many other ceramic objects. They were mostly unpainted like the Uruk period pottery, although a few examples display abstract patterns and reliefs on them.

Ur III

During the Third Ur Dynasty, unpainted ceramic objects were still being created, yet in more elaborate forms, creating vessels out of clay for storing liquids, as well as flowerpots and cake stands. Clay tablets were also produced to keep records by writing on them with styluses made from reed. If the text was meant for archival purposes then it could be baked in a kiln for prosperity.

Tablets could also be used for keeping stock of animals, workers, wages, and other daily administrative tasks.

Babylonian Ceramics

Ceramics produced during this period indicates a marked return to the use of abstract patterns painted on the surface of the pottery, as well as a further increase in the array of forms available for various purposes, both practical and aesthetic. Ceramic Mesopotamian artifacts from this period such as jars, vases, and goblets have been found with remnants of abstract painting on the clay exterior.

Sculpture in Mesopotamia

For more than 2000 years, Mesopotamian art and sculpture had been created for political and devotional reasons, however, the method in which those purposes were conveyed has differed greatly from one period to the next. Based on the most recent archeological research, sculpture from Mesopotamia can be dated back to the 10th millennium BCE, before humans began to settle and the rise of civilization began. Common motifs were animals and human forms, as well as seals with imagery and cuneiform writing inscribed on it.

Sculptures were made from a variety of materials such as stones like gypsum and alabaster, metals like bronze and copper, as well as traditional terra cotta.

Hunter-Gatherers and Samarra

The sculptures that have been found by archeologists from this period are all light and small. This is due to the reason that hunter-gatherers were nomadic and constantly on the move. Therefore it made sense that their sculptures were portable and not heavy to move over long distances.

Once agricultural practices became common, many artists still chose to create small sculptures for personal devotional or ritual use.

Many of these sculptures were fertility figures, made obvious by the exaggerated features and proportions of the female’s breasts, thighs, and buttocks. A prime example of this is the female statuette found in Samarra dating to 6000 BCE which is currently on display at the Louvre Museum. Typical of the period, the sculpture displays little or no facial features or hands or feet, but rather emphasized the reproductive organs of the female anatomy, her thighs even bent in a position suitable for labor.

Uruk Period Sculpture

The sculptures of the Uruk period reflect concepts such as communication and spirituality. A prime example from this period of the late prehistoric era is the Uruk trough, dating to around 3300 BCE. Historians suggest that the trough made from gypsum was part of an offering created for the goddess of fertility and love, Inanna. The exterior of the Uruk trough is decorated with various sacred objects commonly associated with the goddess such as reliefs of reeds and animals.

Based on these observations, historians believe it was used for spiritual or ritual reasons rather than for agricultural use.

Early forms of document notarization have been found from this period in the form of cylinder seals, which were carved from stone and contained images of animals, and early language systems. These were used by officials or their representatives as a kind of official signature, by rolling the cylinder in wet clay, leaving a graphic imprint behind. These cylinders were also used as jewelry and have been found in the tombs of nobility along with their valuable stones and precious metals.

Imagery with a strong narrative quality was the popular motif of the period as can be seen in the cylinders, troughs, and other examples of sculpture from this period.

This period is also marked by a noticeable improvement in the portrayal of the human body and face, as can be observed in the sculpture from around 3000 BCE, the Mask of Warka, or the Lady of Uruk. The marble mask was named after the city it was found in and it is all that remains of a sculpture that once consisted of a body made from wood, with hair made of gold leaf, and eyes and eyebrows inlaid with jewelry. As was common at the time, the sculpture was painted to create a more life-like appearance but has since faded.

Early Dynastic Period

During the Early Dynastic Period of 2900 to 2400 BCE, the sculptors of art in Mesopotamia created works that built on the older traditions and developed styles that became more complex with time. Copper was now the most prominently used medium, although many artists still used stone and clay. The subject matter of sculpture during this period was focused on religion, social interaction, and war.

Cylinder art during this period becomes increasingly detailed, as can be observed in the seal that was discovered in the tomb of Queen Puabi.

The seal is split into a top and bottom register and depicts a palace feast celebration scene with the Queen and her subjects who can be seen sitting at a banquet table, and on the lower register, the King is sitting with his subjects. The King and Queen both appear larger than their subjects, a form of visually denoting rank called the hieratic scale. There is also cuneiform inscribed on this fine example of sculpture in ancient Mesopotamian arts.

Another notable sculpture from this period was found in the tomb of Puabi in Ur.

The bull’s head was a mixed-media sculpture and consisted of a golden head, fur made from lapis lazuli, and horns made from shell. Based on similar bull’s heads found at ceremonial sites by archeologists, the head most likely was used to decorate a lyre used in ceremonies and burial rituals, although most of the lyre found at Puabi’s tomb has disintegrated over the centuries.

Sculptures depicting the human form have also been used as religious offerings in the temples of Mesopotamia.

The most well-known examples of these are the Tell Asmar figures dated from somewhere between 2700 and 2600 BCE. This group of 12 human sculptures depicts gods, priests, and worshippers, and were created in the hieratic scale, as with the cylinders of Queen Puabi.

The sculptures representing worshippers were created with the arms positioned in a manner to suggest the offering of gifts to the gods. Depending on the position on the hierarchical scale, the sculptures were made from materials ranging from gypsum to limestone to alabaster.

The common feature of all the human figures is the large hollow pupils which once held stones in the hollows to create a more realistic appearance. The eyes represented significant spiritual power, especially in regard to the eyes of the gods. One of the figures depicts the powerful god of Mesopotamia, Enil, and is made from limestone, shell, bitumen, and alabaster.

Akkadian Empire

The period of the Akkadian Empire lasted from 2270 to 2154 BCE, and the sculpture of that period grew increasingly themed around war and politics, and the style grew exponentially more life-like in its representation of the human form.

Much of the sculpture art of Mesopotamia from this period depicts a mixture of realistic and stylized features as can be seen in the bronze portrait of King Sargon.

While his facial hair and eyes are stylized, his nose and mouth are created with a naturalistic style and give the impression of a unique individual, which was rare for the time. The eyes of the King Sargon portrait are hollow as they were once inlaid, and the head was cast using the lost wax process.

The Akkadian period was one of massive oppression and upheaval, resulting in a very violent climate.

This can be seen in the examples of art left from that era such as the depiction of the Victory Stele of Naram Sin from the 12th century BCE. The king is represented wearing a horned helmet, signifying that he is a divine figure. Naram Sin is depicted as larger than the other figures such as his enemies and soldiers, typical of the hieratic style. His soldiers watch the scene from a vantage point as Naram Sin stands atop of the dead enemy soldiers. To enhance the drama of the scene, the event has been created in high relief. The cuneiform text provides context on the right side of the panel.

Babylon and Assyria

As the Middle Bronze Age gave way to the Late Bronze Age in the second millennium BCE, Assyria and Babylonia became the most prominent cultures of the era in the Near East. Although stone was also used for sculpture, clay was the most commonly used material. The Mesopotamian artifacts from this period reveal mostly the production of small free-standing sculptures, cylinder seals, and reliefs, as well as non-expensive plaques of molded pottery for domestic religious use.

During the period of Babylonian culture, depictions of humans became more naturalistic and less stylized than before.

The Assyrians developed their own style of huge and gorgeously detailed reliefs in painted alabaster or stone. These reliefs mostly portrayed activities that were practiced by members of royalty, such as hunting or battles, and were intended to be housed in palaces. Animals such as lions and horses are depicted in great detail while humans were posed in comparatively rigid stances, but also contain great attention to detail.

The Assyrians did not produce many sculptures that can be viewed from every angle, except for the massive guardian sculptures, normally winged beasts or lions, that would be positioned next to the gateways to royal premises.

Assyrians were initially hugely influenced by the style of the Babylonians but began to display distinctive Assyrian characteristics around 1500 BCE.

An example of Mesopotamian art from this period is the Burney Relief, created somewhere between 1800 and 1750 BCE. This terracotta plaque is from the Old-Babylonian period and portrays the Queen of the Night, a naked and winged goddess flanked by a pair of owls and sporting bird talons for feet. This high relief sculpture is particularly notable for its size and distinctive iconography, which hints at its use in a cult ceremonial setting.

Mesopotamian and Babylonian Architecture

To the ancient people of Mesopotamia, the craft of architecture was a divine gift from the gods. A lack of suitable building stone in the region made clay and sun-baked bricks the material of choice for building structures. Pilasters and columns were common features of Babylonian architecture, as well as painted frescoes and the use of enameled tiles.

The architects of Assyria were hugely influenced by Babylonian architecture, but built their palaces out of brick and stone.

These Assyrian palaces used lines of slabs that were naturally colored instead of painted. The load-bearing architectural design was the dominant building style, however, structures like the Ishtar Gate from the sixth century BCE were greatly influenced by the invention of round arches in Mesopotamia during this period.

Domestic Architecture

During the early days of life in Mesopotamia, it was up to members of the family to construct their own houses. Most houses were made of wooden doors, mud bricks, and reeds. There were no windows as houses were usually load-bearing, so the only openings of the shelter would be the door.

There was a distinct division between public and private life in Sumerian culture, meaning that very few interiors of homes could be viewed directly from the street. Depending on family size and social status, the houses would vary in size, but the layout was generally the same with the space being divided up into one large central room and smaller rooms built around it.

During the Ubaid period, it became common practice to incorporate courtyards into the designs to help create a natural air coolant, a practice that still continues today in modern Iraqi architecture.

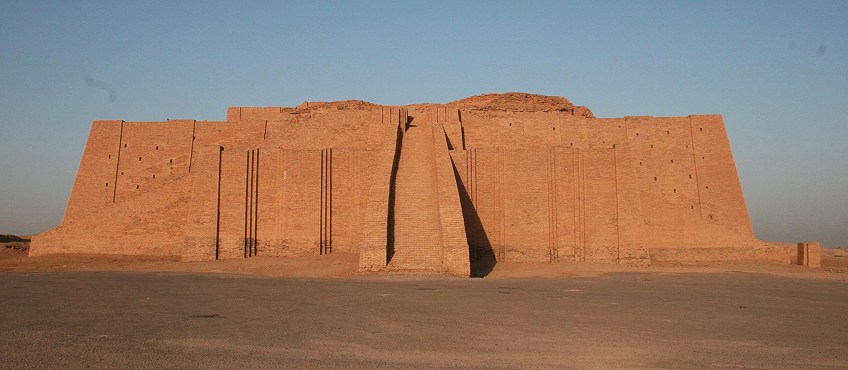

Ziggurats

Every ancient culture of distinction reached an era of creating huge monuments as can be seen in Egypt and ancient sites in South America and even Asia. For the people of the Mesopotamian culture, one of the most incredible achievements was the construction of their ziggurat structures. Ziggurats are similar to pyramids, consisting of terraced steps with receding levels that were built by piling and stacking very large cuts of stone. Ziggurats would usually have a temple or shrine at the top of the steps.

These beautiful examples of Mesopotamian architecture were only allowed to be entered by priests and other religious officials for the offering of gifts and temple maintenance and were not open to the public for worship or visitations. The oldest surviving examples of ziggurat architecture were created in the fourth millennium BCE by the Sumerian culture. The ziggurat style continued to be a commonly used architectural form from the fourth millennium BCE into the early second millennium BCE.

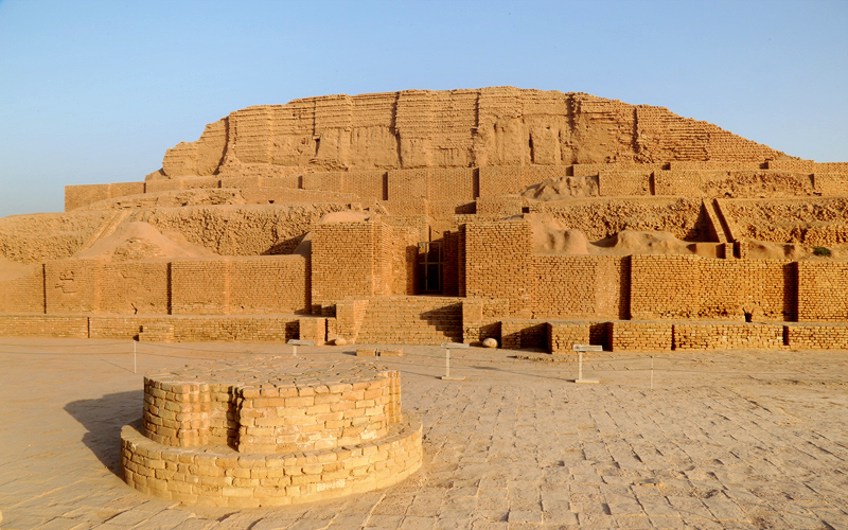

A beautiful example of ziggurat architecture is the Chogha Zanbil Ziggurat built in 1250 BC. It was built in honor of Inshushinak, the Elamite god, by the king of Elam, Napirisha.

After studying the sizable width and height of the ziggurats, modern-day archeologists and architects have suggested that they were created using a system of pulleys and ramps to hoist the massive bricks up the sides of the structure. The topography of Mesopotamia became increasingly higher as older buildings were built on top of crumbing older ones, due to the deteriorating quality of sun-dried bricks as compared to oven-baked bricks.

Throughout the Babylonian and Assyrian empires, sun-baked bricks were the most commonly used building material.

Political Architecture

Public Mesopotamian buildings such as palaces and temples were highly decorated on the outside with features such as enameling, gold leaf, and vibrant paint colors. Many elements were multi-functional and were used for structural support and decoration, such as terra cotta panels and color stones used to delay the deterioration of the public structures as well as strengthen the public buildings. Durable masonry such as stone became more prominently used between the 13th and 10th centuries BCE, as Assyrians used it to replace the sun-baked bricks.

Paint was replaced by bas reliefs and colored stone as commonly used decoration materials.

The Mesopotamian drawings and sculptures produced under Ashurnasirpal II, Sargon II, and Ashurbanipal show us how Mesopotamian art grew and evolved from vibrant yet child-like to subdued and naturalistic over these periods.

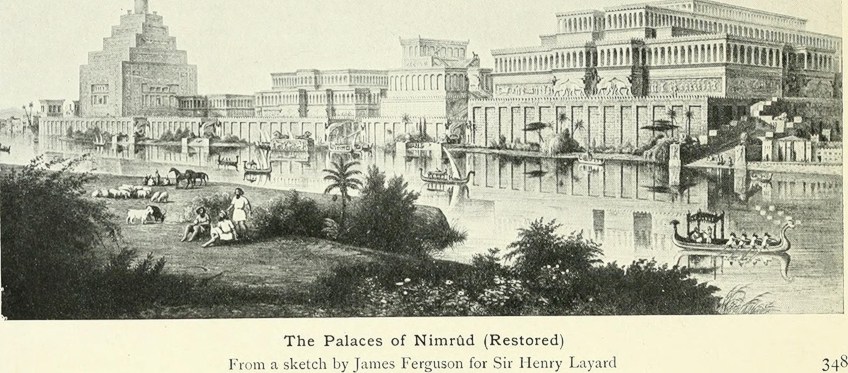

From 2900 BCE (Early Dynastic period) to 612 BCE (Assyrian Empire period), palaces grew immensely in complexity and sheer scale. These early palaces were, however, still much larger than the architecture of domestic homes as well as ornately decorated to set them apart from domestic architecture.

Palaces were often laid out like small cities, as they had to support entire royal families as well as all their servants.

These huge structures included temples, sanctuaries, and places to house and bury the dead. Similar to the architecture of the domestic structures, architects added a courtyard to these spaces in order to facilitate airflow and temperature regulation. These courtyards would also function as ceremonial spaces and served utilitarian purposes as well.

During the reign of the Assyrian Empire, palaces began to be fitted with their own gates and the walls were highly decorated with narrative reliefs. A prime example of this style is the alto relief at the entry gate of the Palace of Dur-Sharrukin.

Belonging to Sargon II, the palace gate featured the mythological Babylonian creature known as the Lamassu, which had the body of a bull, huge wings, and the head of a man.

In other examples of this deity, his head is facing forward and they wear conical caps. Sometimes the body is that of a lion instead of a bull, in some versions the deity assumes a female form. These mythical creatures, also known as Shedu, can be found in the literature and art of Mesopotamia as far back as 5500 BCE and looking over the palace of Persepolis circa 550 BCE.

A structural system that often gets accredited to the Romans was originally created by Mesopotamian engineers, and that is the round arch. While the normally used load-bearing walls were not strong enough to handle the pressure of too many windows or doorways, by adding round arches, the structures could absorb more of the pressure, which allowed for the inclusion of larger openings in their architecture for improved wind flow and sunlight.

Examples of round arches in Mesopotamian architecture can be found as far back as the eighth century BCE where they were used in the entryways of palaces such as Dur-Sharrukin, where it is used in the central portal as well as in windows on the left and right of the entrance.

The most famous example of the round arch in Babylonian architecture can be found in the Ishtar Gate from 575 BCE.

The gate is now housed at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin but was originally part of the Processional Way of the Babylonian city. This ornate gate is beautifully decorated with lapis lazuli and portrays various bas reliefs of animal figures and floral motifs that were connected to Ishtar, the goddess of war and fertility in some sacred manner.

Today we have learned about the art of the oldest civilization on earth, the Mesopotamians. Mesopotamian buildings and architecture were also discussed in length to give us insight into the daily lives of the people of that era. No Mesopotamian drawings exist today, as the art of Mesopotamia was mostly based around the creations of sculpture, ceramics, painting, and the construction of Mesopotamian buildings.

Take a look at our Mesopotamian art period webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Does Mesopotamia Still Exist Today?

Mesopotamia refers to a region from ancient antiquity which is now known as the countries of Iran, Turkey, and bits of Iraq and Syria, mostly situated between the Tigres/Euphrates River systems and their associated canals.

What Are the Most Common Forms of Mesopotamian Art?

The art of Mesopotamia ranges from the early use of ceramics which were painted with abstract patterns, to the creation of sculpture effigies for religious purposes, and styles used in Mesopotamian architecture to create their ornate temples and palace gates. The first available art tools were clay tablets and reed carving tools, and although sculpture and carving were popular, there were no drawing tools, therefore no examples of Mesopotamian drawings.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Mesopotamian Art – Exploring the Architecture and Art of Mesopotamia.” Art in Context. December 1, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/mesopotamian-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 1 December). Mesopotamian Art – Exploring the Architecture and Art of Mesopotamia. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/mesopotamian-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Mesopotamian Art – Exploring the Architecture and Art of Mesopotamia.” Art in Context, December 1, 2021. https://artincontext.org/mesopotamian-art/.