Hall of Bulls Lascaux – An Exploration of the Lascaux Cave Paintings

The Lascaux cave system is a group of caves in southwestern France. The Great Hall of Bulls paintings can be found in these caves, which are situated close to a village called Montignac. Over 600 different Hall of Bulls Lascaux paintings adorn the ceiling and walls of the cave. The Lascaux cave paintings depict large animals from the Upper Paleolithic period and are thought to be around 17,000 years old.

The History of the Hall of Bulls Lascaux Paintings

The Great Hall of the Bulls paintings are the result of multiple generations of contributing artists. The original Hall of Bulls location has not been available to be viewed by members of the public since 1963, nevertheless, there are now many replicas that were created long after the Hall of Bulls time period. But why were they painted and what medium was used on the Hall of Bulls? Let us find out more about the fascinating Lascaux cave paintings.

| Hall of Bulls Location | Montignac, France |

| Period | Upper Paleolithic |

| Medium | Mineral Pigments |

| Artists | Unknown |

The Discovery of the Great Hall of the Bulls

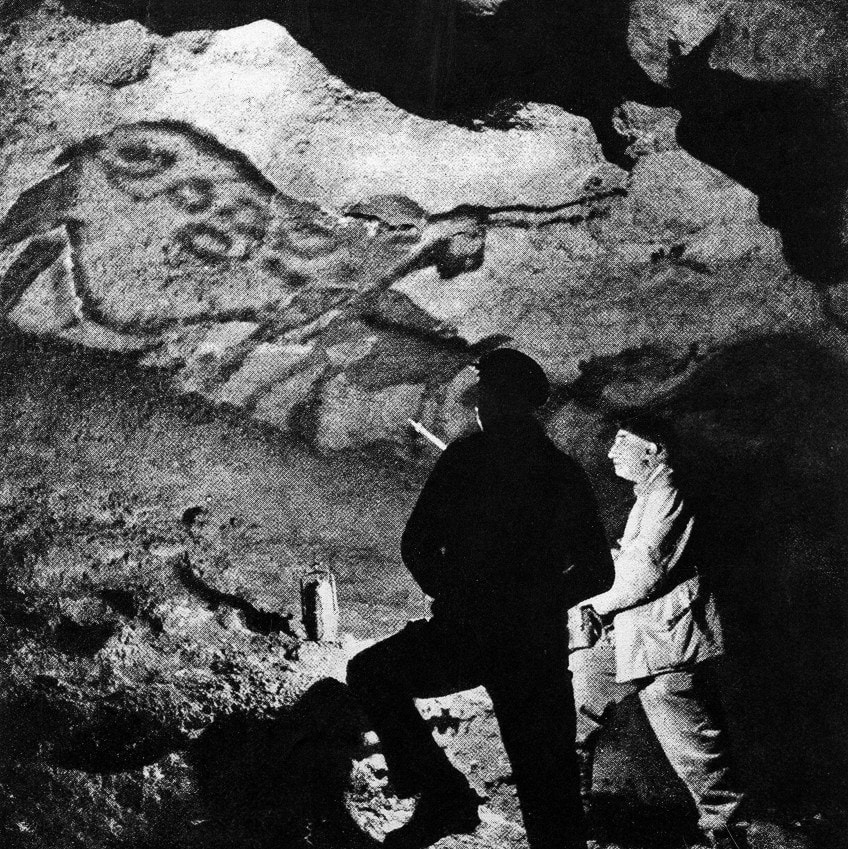

When his dog fell into a crevice on the 12th of September, 1940, Marcel Ravidat found the opening to the Lascaux Cave. He later returned to the site, accompanied by three friends. They accessed the caves by a tunnel that ran for around 15 meters which they thought was the fabled secret entry to the neighboring Lascaux Manor. The youngsters realized that the walls of the caves were filled with animal images. Titles were given to passageways that reflect consistency, setting, or simply symbolize a cavern, such as the Shaft, the Passageway, and the Great Hall of the Bulls.

They revisited the Lascaux caves on the 21st of September, 1940, along with Abbé Henri Breuil who would produce numerous illustrations of the Lascaux cave paintings, several of which are utilized as study guides today owing to the terrible deterioration of many of the Hall of Bulls paintings.

The Lascaux cave system was presented to the general public on the 14th of July 1948, and the first academic research, centered on the Shaft, began a year afterward. By 1955, the Hall of Bulls paintings had been clearly destroyed by the carbon dioxide, temperature, moisture, and other impurities created by 1,200 people every day. Lichen and fungi attacked the surfaces as the air quality degraded.

As a result, the cave was permanently closed in 1963, the murals were returned to their original form, and a daily tracking system was implemented.

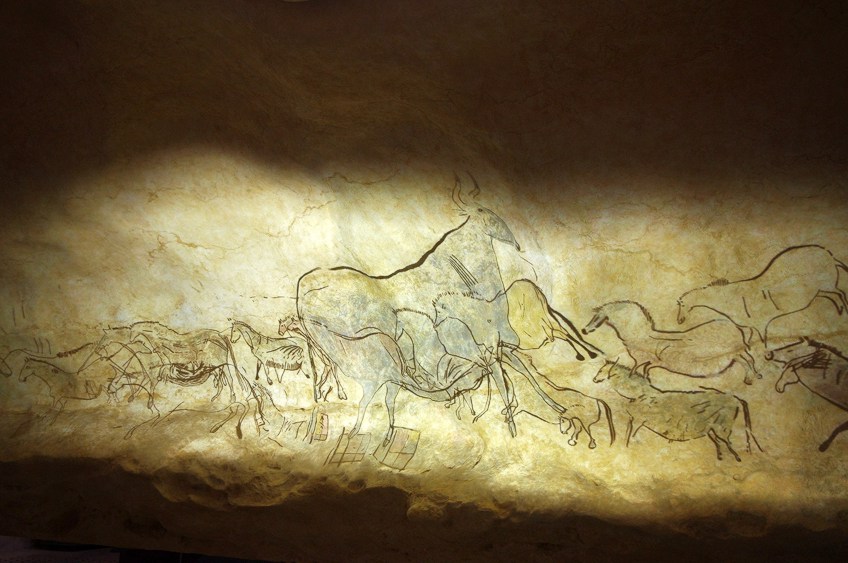

Replicas of the Hall of Bulls Paintings

Due to conservation issues in the actual cave, the manufacturing of copies has become more vital. Lascaux II, an exact replica of the Painted Gallery and the Great Hall of the Bulls, was presented at the Grand Palais before being showcased about 200m from the initial cave beginning in 1983, as a negotiated settlement and endeavor to display an image of the paintings’ magnitude and subject matter for the general populace without endangering the original versions.

A whole spectrum of Lascaux’s art is on display in the Center of Prehistoric Art, close to the actual site, in which there are also live creatures representing ice-age species. The cave paintings for this location were recreated using the same substances, such as charcoal, iron oxide, and ochre, that were thought to have been employed 19 thousand years ago.

Other Lascaux replicas have also been created over the decades. Lascaux III is a set of five precise replicas of the cave paintings that have been traveling around the globe since 2012, providing information about Lascaux to be conveyed far from the source. Lascaux IV is a fresh reproduction of all the decorated regions of the cave, which is part of the International Center for Parietal Art.

This bigger and more realistic duplicate, which incorporates digital media into the show, has been on exhibition since December 2016 in a new exhibit erected by Snhetta within the ridge overlooking Montignac. French crockery from the region, adorned with pictures of the Lascaux cave paintings, was previously abundant and marketed as objet d’art and mementos in the neighboring communities, but is now hard to locate since the pictures have been trademarked. Copies of the paintings may only be purchased via the Lascaux museum shop.

Location of Artworks

The Vézère drainage system, with its sedimentary makeup, includes the northerly portion of the Black Périgord. The river’s path is defined by a sequence of bends surrounded by steep limestone cliffs that define the scenery at its center. The slopes of the terrain soften somewhat upstream from this steeply graded topography, around Montignac and in the neighborhood of Lascaux; the hillside spreads, and the river banks reduce their incline.

The Lascaux region is some way from the primary clusters of painted caves and occupied settlements, the majority of which were uncovered lower downstream.

There are 37 painted caves and dwellings in the vicinity of the community of Eyzies-de-Tayac Sireuil, and an even larger proportion of Upper Paleolithic settlement locations in the open air, behind a protective overhanging, or at the mouth to one of the area’s limestone holes. This is Europe’s highest proportion.

The Images

Nearly 6,000 images are found in the caves, which are divided into three categories: creatures, humans, and abstracted signals. There are no pictures of the area surrounding or plants in the artwork. The majority of the primary figures were painted into the walls with yellow, red, and black paints derived from a diverse array of mineral colors, comprising iron compounds such as iron ochre, goethite, and hematite as well as pigments containing manganese.

Charcoal might also have been used as well, although only sparingly. The color on parts of the walls of the caves may have been administered as a pigment solution in either animal fat or cave groundwater or sometimes clay, resulting in pigment that was patted down or wiped on rather than brushed with a tool. In some regions, the color was added by blasting the colors through a pipe after blowing the solution through it.

Some motifs have been etched into the rock where the surface is softer. Many images are too weak to be seen, while others have completely faded.

Over 900 creatures have been recognized as such, with 605 of these being properly recognized. There are 364 artworks of horses and 90 pictures of stags among these photos. Cows and buffalo are also depicted, accounting for 4 to 5% of the photos. Seven cat-like animals, a bird, a rhinoceros, a bear, and a human being are among the other pictures. There is only one representation of a reindeer, despite the fact that these animals were the painters’ primary source of sustenance. Geometric patterns were also discovered on the walls.

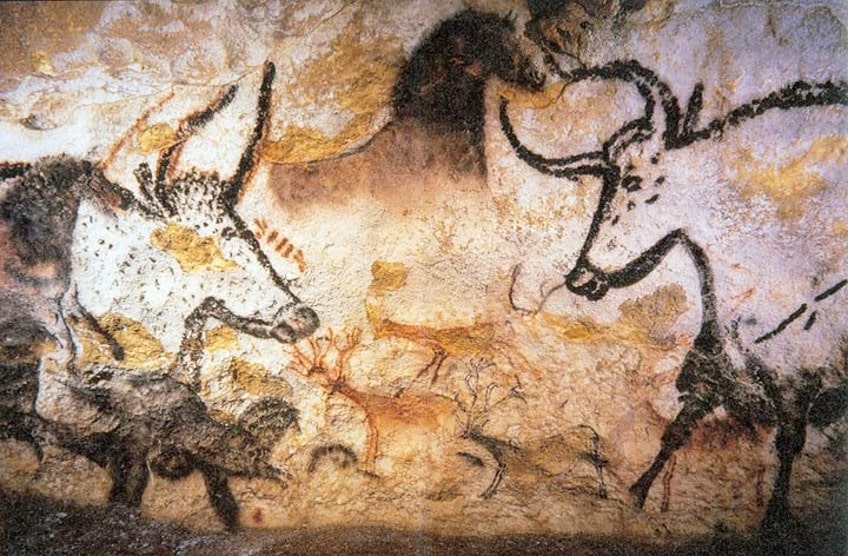

The most renowned area of the cave is The Great Hall of the Bulls, which depicts bulls, horses, stags, and the location’s sole bear. Among the 36 beasts depicted here, the four bulls, are the dominating figures. One of the bulls is 5.2 meters long, making it the biggest animal uncovered in cave art thus far. Furthermore, the bulls look to be moving. An image that is known as The Crossed Bison, is frequently cited as an instance of the Paleolithic cave artists’ talent. Because the rear legs are crossed, it seems like one leg is nearer to the spectator than the others. This scene’s optical breadth exhibits a rudimentary kind of viewpoint that was unusually sophisticated for the period.

Representation of the Parietal

The Hall of the Bulls has Lascaux’s most stunning creation. Because its calcite walls are not ideal for engraving, it is exclusively ornamented with paintings, which are frequently of amazing size: a few are up to five meters in length. Two rows of aurochs face each other. On the northern edge, the two aurochs are followed by roughly ten equines and a gigantic mysterious creature with two lines on its brow, earning it the moniker “unicorn.”

On the southern side, three big aurochs stand next to three smaller pieces, all painted crimson, as well as six little animals and the cave’s solitary bear, which is overlaid on an aurochs’ stomach and is hard to interpret.

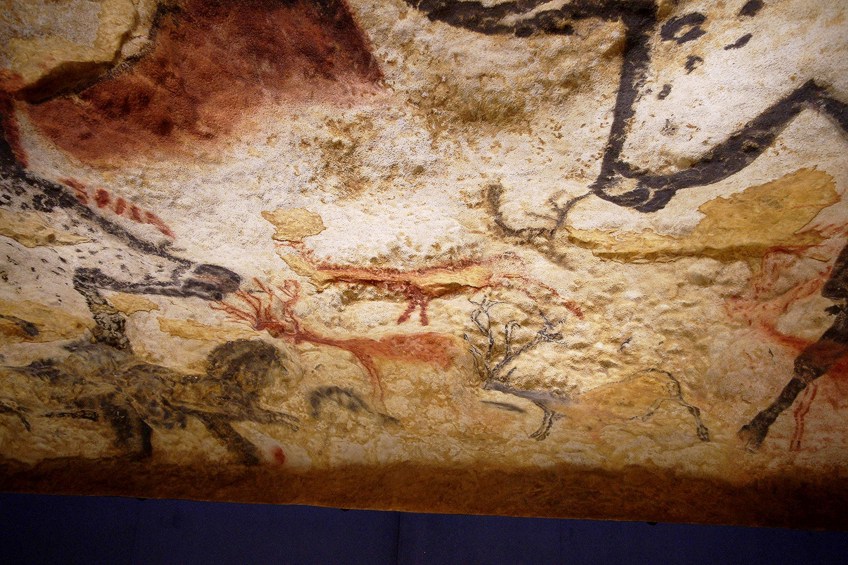

Cows and mares are also shown on the Axial Diverticulum, along with ibex and deer. 2.50 meters above the earth, a painting of a galloping horse was stroked with a manganese pencil. Some creatures are placed on the ceiling and appear to move from one wall to the next.

These images, which necessitated the use of a framework, are interlaced with a variety of symbols (dots, sticks, and rectangular signs).

The Passage‘s ornamentation has been severely deteriorated, owing mostly to air movement. The images in the Nave are divided into four groups: the Black Cow panel, the Empreinte panel, the Crossed Buffalo panel, and the Deer swimming panel.

The Feline Diverticulum is named after a grouping of big cats, one of which appears to urinate to establish its domain. There are engravings of wild creatures in a pretty naïve manner there, which is really difficult to reach. Other creatures are paired with symbols, including a frontal view of a mare, which is unusual in Paleolithic art, when animals are often depicted in profile or from a “warped viewpoint.” Upwards of a thousand carvings matching creatures and symbols may be found in the apse, some of which are placed on murals.

There is only one reindeer shown at Lascaux.

The Well has Lascaux’s most mysterious scene: an ithyphallic person with a bird’s head appears to be lying on the floor, maybe struck down by a bison pierced by a lance; at his side is an extended item topped by a bird, while on the side a rhinoceros wanders away. Several explanations of what is depicted have been proposed.

On the other wall, there is likewise a horse. This arrangement contains two types of signs: Between the rhinos and man, three pairs of punctuation signs discovered at the base of the Cat Diverticulum, in the cave’s most isolated region; between bison and man, an intricate barbed symbol that can be discovered almost completely identical on other walls of caves, as well as paddle marks and a lamp made from sandstone.

Interpretations of the Hall of Bulls Lascaux Paintings

The analysis of Palaeolithic Art is difficult since it is impacted by our own preconceptions and assumptions. According to some anthropologists and intellectuals, the drawings might be a record of previous hunting prowess or a supernatural ritual to boost future killing attempts.

The overlapped views of one group of creatures in the same cavern site as another group of creatures support the latter argument, implying that one region of the cave was more effective in forecasting an abundant hunting expedition.

Thérèse Guiot-Houdart tried to understand the representational purpose of the wildlife, classify the motif of each picture, and finally reassemble the painting of the myth depicted on the rock walls by trying to apply the archetypal technique of assessment to the Lascaux cave paintings (studying place, orientation, and dimensions of the creatures; organization of the content; painting method; allocation of the color planes; investigations of the image center).

Julien d’Huy demonstrated that some angular or pointed Lascaux signals may be analyzed as injuries. These indications are more common in hazardous species, such as large felines, aurochs, and bison, and could be interpreted by a dread of the image’s motion. Another study lends credence to the notion of half-alive pictures. Bison and ibex are not depicted side by side at Lascaux.

In contrast, there is a bison-horse-lions system and an aurochs-horse-deer-bears system, with these creatures regularly connected.

A distribution like this might reveal the link between the species depicted and their environmental circumstances. The pictorial region is known as the abside, or apse, a rounded, semi-spherical chamber comparable to an apse in a Medieval church, which is less well-known. It has a circumference of around 4.5 meters and is decorated with thousands of intertwined, overlaying, etched designs on every wall surface.

The Apse’s ceiling, which is around two meters high, is so fully covered with such carvings that it seems the prehistoric humans who performed them first built a scaffold. This form of art, according to Jean Clottes, who researched apparently comparable art of the San tribes of Southern Africa, is religious in character, referring to images encountered during ceremonial trance-dancing. Because trance visuals are a function of the human brain, they are not affected by geographical area.

Nigel Spivey, a lecturer of classical art and archeology at the University of Cambridge, has proposed in his studies that dotted and lattice patterns overlaying figurative pictures of creatures are extremely similar to visions caused by sensory deprivation.

He goes on to say that the links between culturally significant animals and these visions led to the birth of image-making or art. André Leroi-Gourhan examined the cave beginning in the 1960s, and his observations of animal connections and animal dispersion within the cave prompted him to establish a Structuralist thesis positing the possibility of a true organization of pictorial space in Palaeolithic shelters.

This concept is built on a feminine/masculine duality that can be seen in both the symbols and the creature depictions, most notably in the horse/bison and horse/aurochs pairings. He also described a continuous progression via four successive phases, from Aurignacian to Late Magdalenian. Leroi-Gourhan did not provide a full examination of the figures in the cave.

These artworks from the “Hall of Bulls” time period are very rare examples of Upper-Paleolithic artworks. They were most likely created to portray a successful hunt or perhaps a trance-inducing vision quest. The Lascaux cave paintings are not open to the public, but there are many replicas that can give one a sense of the majesty and scale of the artworks.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Medium Was Used on the Hall of Bulls Paintings?

The bulk of the basic figures were painted into the walls with yellow, red, and black paints derived from a wide range of natural hues, including iron compounds such as iron ochre, goethite, and hematite, as well as manganese pigments. Charcoal may have been used as well, but only sparingly. The color on the cave walls may have been applied as a pigment solution in either animal fat, cave groundwater, or clay, resulting in pigment that was slapped down or wiped on rather than brushed with a tool. The color was added in certain areas by blasting the colors via a pipe after blowing the solution through it.

What Was the Function of the Lascaux Artworks?

According to Jean Clottes, who studied seemingly comparable art of the San tribes of Southern Africa, this kind of art is religious in nature, relating to pictures observed during ritual trance-dancing. Trance images are not impacted by geographical location because they are a function of the human brain. Nigel Spivey, a lecturer in classical art and archeology at the University of Cambridge, has argued in his research that dotted and lattice patterns covering realistic representations of creatures are quite comparable to sensory deprivation visions.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Hall of Bulls Lascaux – An Exploration of the Lascaux Cave Paintings.” Art in Context. December 14, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/hall-of-bulls/

Meyer, I. (2021, 14 December). Hall of Bulls Lascaux – An Exploration of the Lascaux Cave Paintings. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/hall-of-bulls/

Meyer, Isabella. “Hall of Bulls Lascaux – An Exploration of the Lascaux Cave Paintings.” Art in Context, December 14, 2021. https://artincontext.org/hall-of-bulls/.