Suprematism – The Art and Artists of the Russian Suprematism Movement

Developing in the Soviet Union, Suprematism was an art form that resorted back to basic geometric forms and pure abstraction as a way for artists to connect with something purer. Seen as an avant-garde art movement, Suprematism existed as a radical expansion of abstract art that emerged after the First World War. As the movement appeared after both Futurism and Cubism, Suprematism was thought to represent the birth of a new form of art that was in support of a completely new style.

Table of Contents

The Origin of Suprematism Art

Developing in Russia between 1913 and the 1920s, Suprematism was a movement that emerged as a post-World War One art form. Focusing on the expression of pure feeling through simple geometric shapes such as squares, circles, rectangles, and lines, Suprematism artists created artworks in which these forms were painted using an incredibly restricted range of colors.

Supremism, which revolves around the concept of superiority, was also included in these artworks, as feelings were emphasized as opposed to the subject matter.

This progression in artistic expression occurred just before Russia entered into an explosive political revolution that began in 1917. During this time, the old order that had characterized Russia was being done away with, which worked to end imperial rule. This led to the establishment of Stalinism in 1924 and the formation of the Soviet Union, which differed greatly from the previous rule.

Prior to this, Russia was seen as a hub of cutting-edge and extremely innovative art, as the influence of the Constructivism art movement could be seen. However, as Stalinism grew, the freedom of artists was severely limited, and a lot of their artworks were censored. Due to this, the Russian vanguard faced head-on and brutal criticism from the authorities based on the type of art that was produced. The doctrine of Socialist Realism was later introduced in 1934, which went on to prohibit abstraction and deviation of any artistic expression.

Seen as one of the key movements of modern art in Russia, Suprematism was closely associated with the Revolution, as the artworks created directly contested the rules and control that the country was under. Artists went on to produce paintings that focused on the reflection of true feelings and perceptions, with the theme of mysticism being over-emphasized.

At the time of its emergence in the early 20th century, the concept of abstract art was still largely misunderstood. Suprematism was thus an art movement that sought to understand and situate abstract art according to its potential to help humanity in achieving a more significant experience whilst alive.

The goal of Suprematism was to essentially find ways of using abstraction in art to break away from the expectations and restrictions of reality, in an attempt to connect with something purer.

Russian Suprematism

Serving as one of the first and most extreme developments in abstract art to emerge at that point, Suprematism was introduced to the world by Russian artist Kazimir Malevich in 1913. Already an established painter at the time, Malevich went on to develop the concept of Suprematism art after exhibiting work at the Der Blaue Reiter show in 1912. He believed that Suprematism was superior to all the art movements of the past, as it led to the domination of pure feelings and perceptions within artworks in the visual art world.

As Malevich was greatly interested in the works of progressive and experimental poets from the literary group that had emerged in early 20th century Russia, his desire to go against the traditional rules governing language and reason flourished. He went on to establish the notion that very fragile links existed between objects and meaning, which opened up a huge possibility for the introduction of a totally abstract form of art to enter.

As Russian society was drastically changing due to the Revolution that had begun, the politics and culture that had previously governed the country were in a state of turmoil. This led Malevich to become fascinated in the search for art’s barest essentials, which helped pave the way for the emergence of Suprematism. Working at a time where the certainties of the past were decreasing, Malevich recognized how abstract artworks would be able to occupy the gap in art that was previously reserved for traditional and godly paintings.

Malevich was trained as a realistic painter and his early works represented the physical world. However, he felt a disconnect with the Representational art he was producing, as he wondered about the genre’s relevance in an ever-changing world. With Russia modernizing at such a rapid pace and rushing towards the insanity of war, Malevich felt that his realistic paintings did not accurately depict the world he was living in.

This eventually led to him developing an art movement that was able to, signifying the birth of Russian Suprematism.

Kazimir Malevich Suprematism

Inspired by both Cubism and Futurism, Malevich began to experiment with the disintegration and fragmentation of form, which he blended with traditional imagery to create a version of the European avant-garde that was distinctly Russian. This resulted in his iconic 1913 breakthrough while he was working on background and costume sketches for a Futurist opera. His drawings made reference to his Cubo-Futurism influence, with Suprematism seeming like the logical extension of the most important elements of both movements.

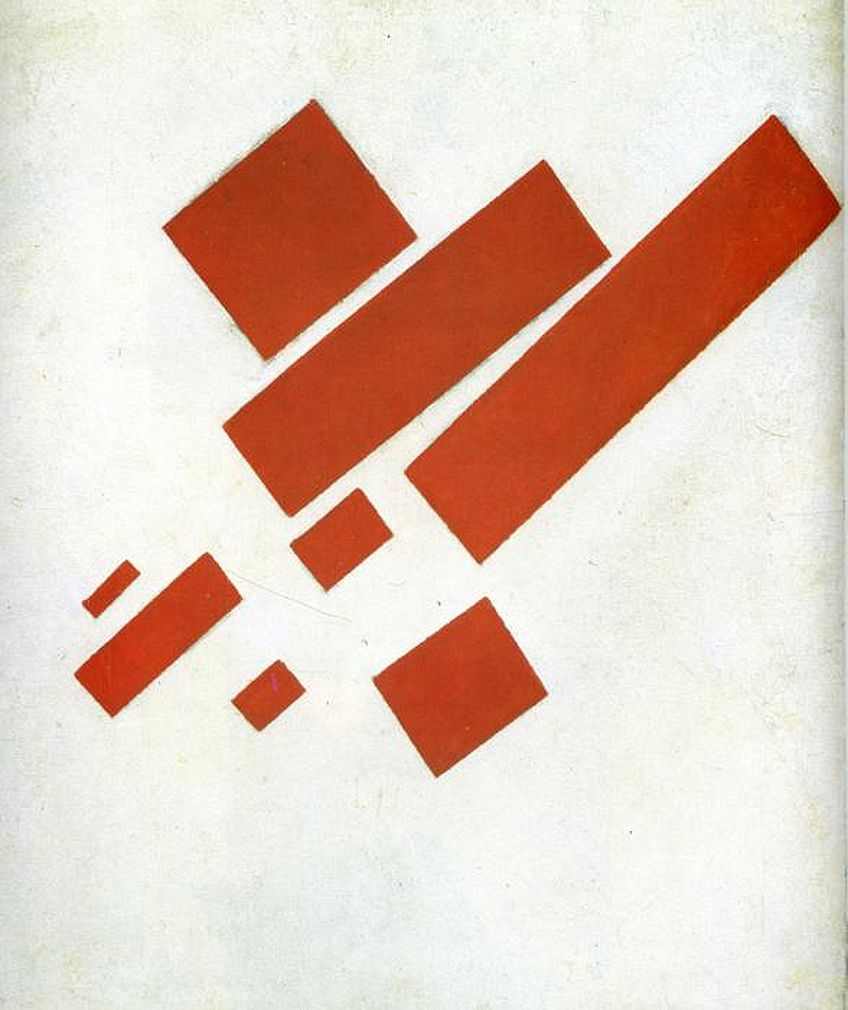

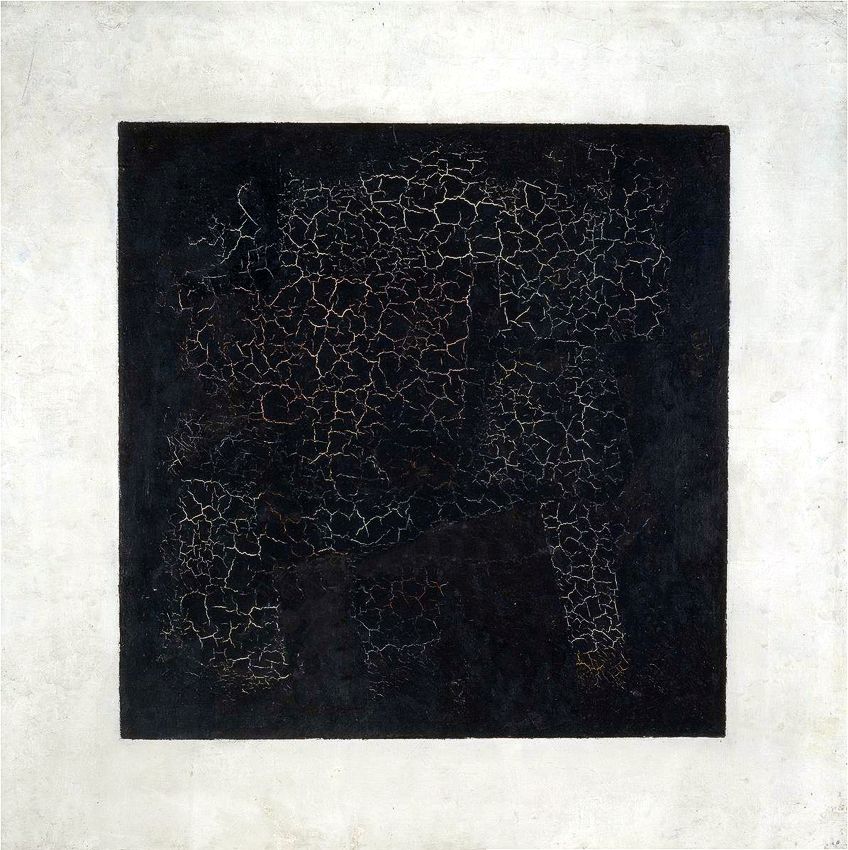

This allowed a connection between basic geometric shapes and a sense of purity to form, with Malevich making use of only squares, crosses, and circles in his early Suprematist artworks. At this time, he frequently made use of a monochromatic color palette, including only reds, greens, and blues when he felt like it. In 1915, Malevich produced Black Square, which quickly became the centerpiece of this new movement, as it seamlessly embodied all of the concepts that Suprematism stood for.

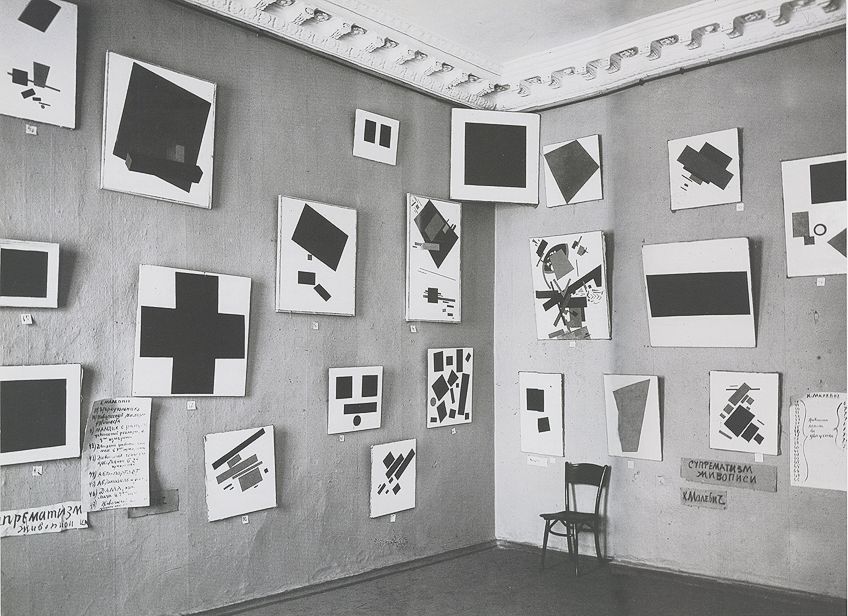

In 1915, Malevich was swiftly joined by a few other Russian artists to formally create the Suprematist art group. Together, they staged an exhibition in St Petersburg called The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10, which went on to exhibit the 36 original artworks that launched Suprematism. Malevich’s Black Square headed the list of works included and was controversially hung in the corner of the exhibition room, which was a space typically reserved for an icon in an Orthodox Russian home.

The inclusion of the zero in the exhibition title was thought to be a reference to the notion that the old traditional way of art had ended, which made way for Suprematism to take over.

The paintings that Malevich displayed were all based on his new geometric style as simple shapes were merely placed on a white background, creating the illusion of movement within his works. In addition to the show, Malevich released a manifesto titled From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism in Art, where he reported to have entered a new awareness of art.

While experimenting with different geometric forms, Malevich began to write about their inherent aesthetic value. He later established a theory that believed that art fit for modernity should try to communicate through a completely abstract and visual language that is based on these simple forms. Malevich stated that the elements of Suprematism were able to surpass rationality in its attempt to reach a total aesthetic form of purity.

By removing all references to potential symbolic meaning, Malevich’s Suprematist paintings were able to achieve a complete abandonment of any representational meaning.

This led to an art form that was able to communicate on a fully abstract level, as forms were reduced to their essential qualities only. As he rejected a narrative subject matter in his works, Malevich ignored both politics and religion, as he replaced both concepts with something exceeding the physical world.

In 1919, Malevich put on a one-man exhibition of his paintings, where he proceeded to announce the end of the Suprematist movement. He later published a book in 1927, titled The Non-Objective World, that went on to become one of the most iconic theoretical documents of abstract art. Within this book, Malevich explained his fascination with the geometric shapes, as he took refuge in the “Suprematist square” as a way to free art from the burden of the physical world.

Malevich went on to declare Suprematism as the new form of “realism” within painting, which proved to be confusing as all his paintings encompassed a basic two-dimensional shape atop a white background. In doing so, Malevich outright dismissed the traditional comprehension of what realism in paintings stood for, as his artworks provided no representation of the world society saw.

Due to the advancements in art, Malevich has long been considered as one of the greatest leaders of non-representational painting in the early 20th century, with the likes of Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian. As an active member in the creation of the modern avant-garde, Malevich published many texts that explained his theories.

However, what made him stand out amongst other artists was that he only wrote his explanatory texts years after he produced his paintings, demonstrating that Suprematist was a largely intuitive discovery.

By 1924, Malevich’s career began to decline. This was due to the combination of Stalin’s rise to power and the enforcement of Socialist Realism, which saw the entire Suprematist movement and his artworks coming under heavy attack. Despite this, the influence of Kazimir Malevich Suprematism proved to be powerful, as it went on to help develop the Modernist art culture within Russia, in addition to other forms of abstract art which can still be seen today.

An Appropriate Suprematism Definition

Named by Malevich after he developed the initial concepts of the movement, the term “Suprematism” was said to describe the superiority of pure feeling or perception in visual arts. Suprematism also refers to abstract art that has been limited to the point where not only the subject matter becomes irrelevant but so do elements like perspective.

This essentially leads to the idea of supremism, which revolves around the elevated importance of feelings.

Despite emerging in 1913, the Suprematism definition was only elaborated on by Malevich in his book that was published in 1927. In his writings, he stated that the title of “Suprematism” was intended to relate to the unadulterated feelings found within creative art. Additionally, Suprematist artworks rendered the visual phenomena found in their paintings as truly meaningless, as the significant thing that the entire movement was based on was the notion of feeling itself.

Suprematism abandoned the concept of realism as it was thought to distract from the spiritual experience that art was meant to prompt. Instead, the movement was viewed as the logical conclusion of Futurism’s interest in motion and Cubism’s reduction of forms from several perspectives.

Thus, the definition of the movement encompassed the use of basic geometric forms that were included in Suprematist artworks, such as squares, circles, rectangles, and lines that were then painted using an incredibly limited selection of colors.

Key Ideas Behind Suprematism

As an abstract art movement, Suprematism was influenced by the search for a “zero degree” of art, which described the point beyond which a painting could not go without ceasing to be seen as art. This led to one of the main ideas within Suprematism art, which was the inclusion of simple motifs. These basic forms were thought to best articulate the shape and flatness of the canvases, with the square, the circle, and the cross quickly becoming the favored symbol of the group.

The reasoning behind the use of such symbols was because they were said to emphasize the texture of the painting, as the feeling of an artwork was another vital quality within Suprematism paintings. As artists viewed the actual subject matter of the visual world to be meaningless, they sought to convey the significance of feeling within their works, which was done through the motifs and texture depicted.

In Malevich’s influential book, The Non-Objective World, he clearly stated what he believed the core concept of Suprematism to be. As the search for pure feeling within creative art was the key idea of the movement, Malevich further emphasized that the essence of Suprematism was to focus on the meaning found within pure abstraction as opposed to reality.

Through removing all elements associated with reality, viewers had to consider their world through the mystic experience caused by the stripped-down forms of abstract art.

This concept forced viewers to consider what kind of picture of the world was presented to them by Suprematism artists. The artworks made attempted to show viewers a fresher and stranger side of the world that had not previously been considered, which made the strong theme of absurdism a key idea behind the movement. Additionally, Malevich was inspired by Russian folk art and the customs of the Russian Orthodox church, with these influences being seen in his Suprematism paintings.

The Phases of Suprematism

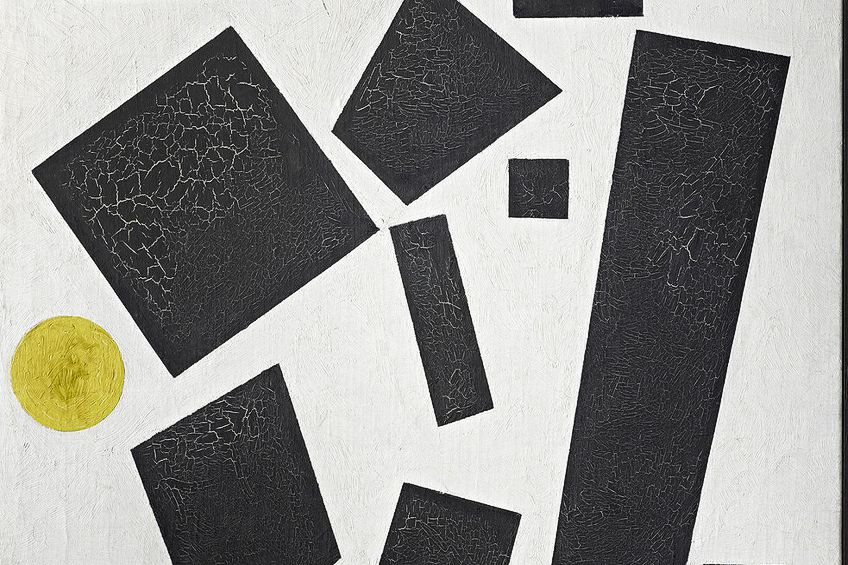

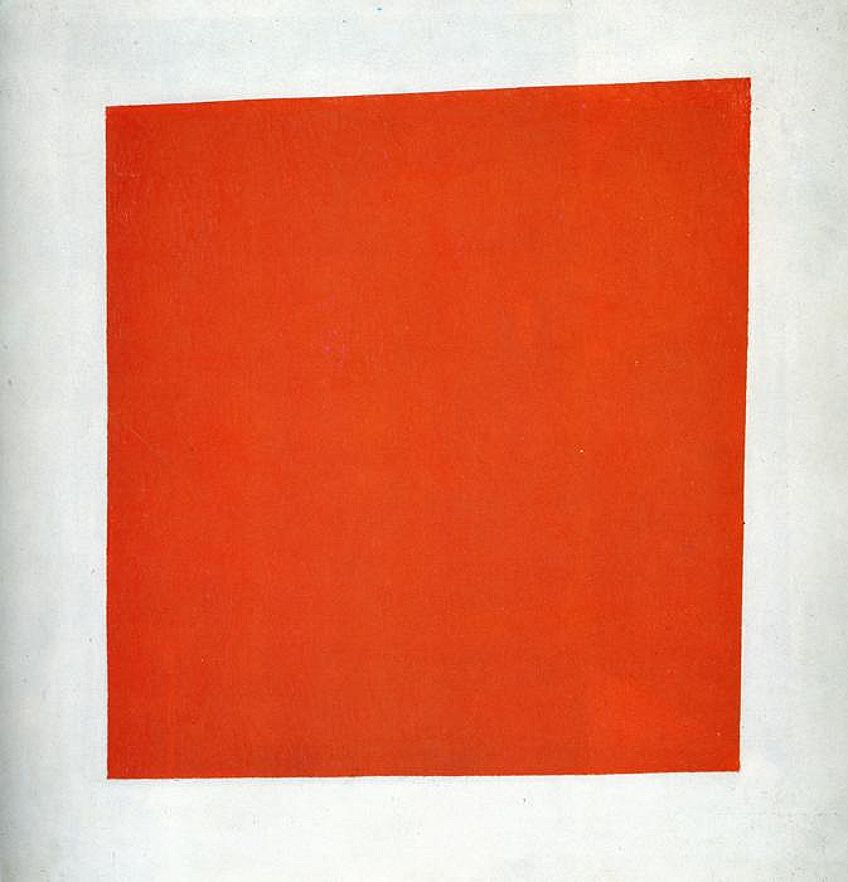

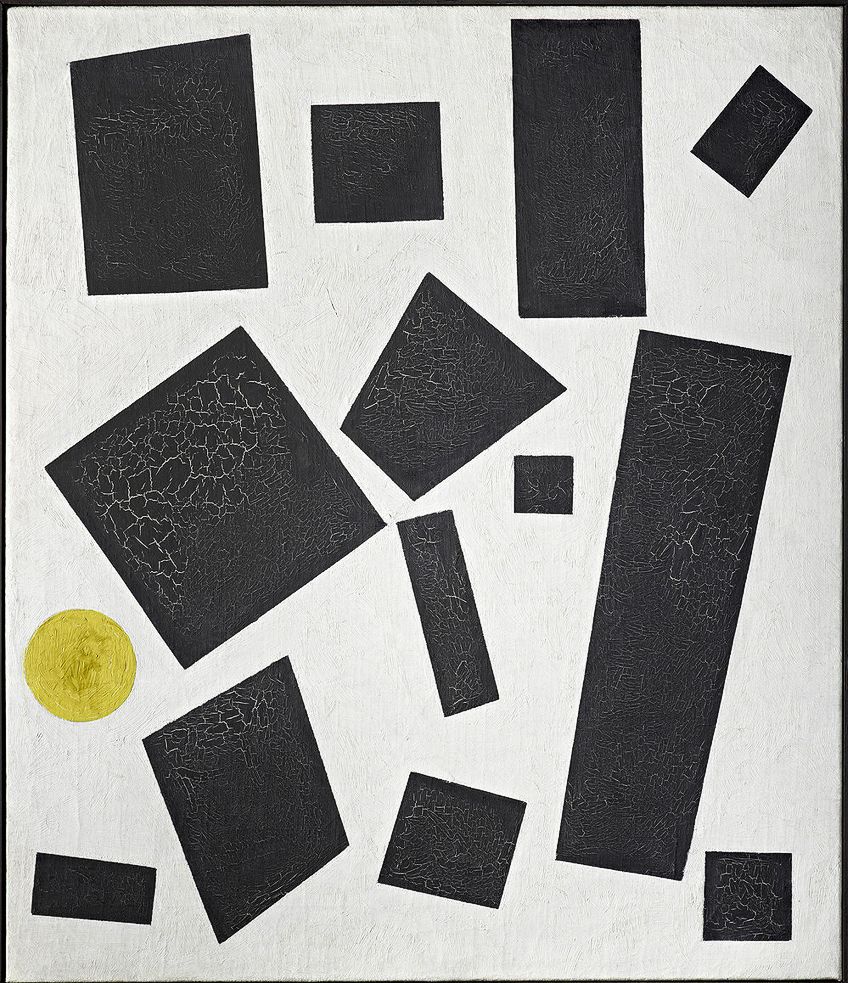

As the movement was spearheaded by Malevich, he divided the development of Suprematism up into three distinct phases based on his own paintings, namely: the black stage, the colored stage, and the white stage. Within each phase, a large number of artworks were produced, that each explored a wide range of different geometric shapes and compositions.

In the first phase, which Malevich titled “black”, the majority of his paintings featured a variety of black forms painted over a white background. This phase was further illustrated by his iconic Black Square, which he painted in 1915. This painting went on to become one of his most well-known artworks, in addition to being viewed as the central element of the first section of Suprematism.

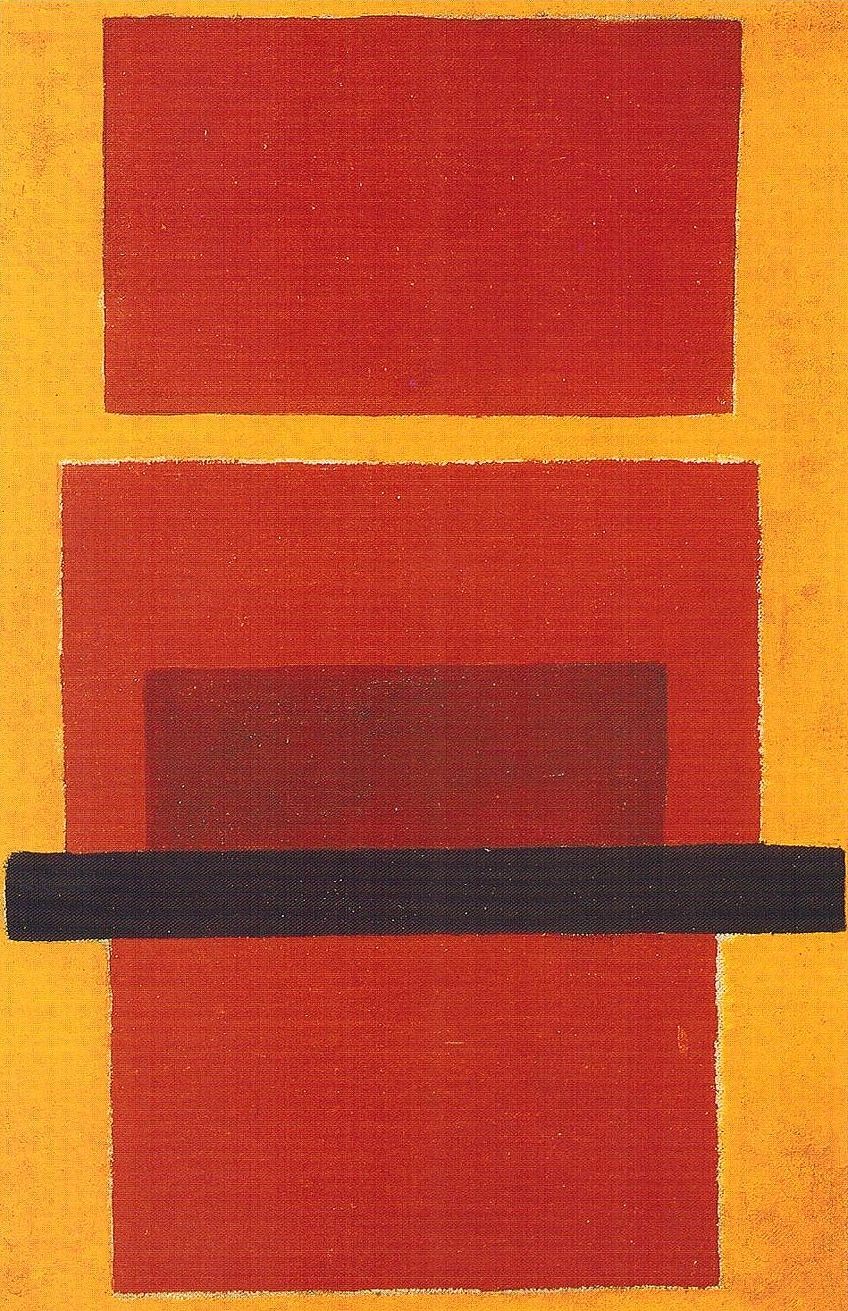

In his second phase, titled “colored”, Malevich began to incorporate some colors into his predominantly monochromatic artworks. Sometimes known as Dynamic Suprematism, Malevich focused particularly on the color red and the use of different shapes to create the notion of movement within this phase.

Through expanding his color palette, Malevich was able to play around with the idea of dimensionality and perception in ways that bewildered any logical and reasonable link between visual relationships and reality.

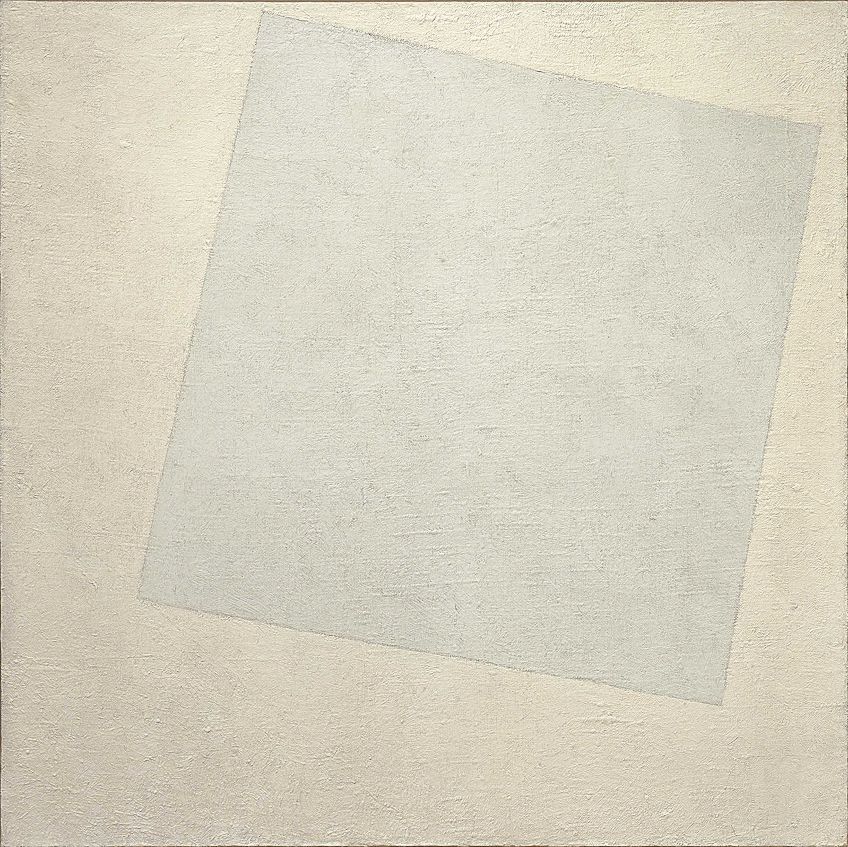

The final phase of Kazimir Malevich Suprematism was known as the “white”, as it consisted solely of white forms that were painted on white backgrounds. Malevich exhibited of all his white stage artworks in 1919 called the Tenth State Exhibition: Non-Objective Creation and Suprematism, where he displayed his groundbreaking painting, White on White (1918). Seen as an innovative artwork of modern monochrome art, White on White represented simply the “idea” of art as no shapes or forms were depicted.

The Most Influential Suprematism Artists and Their Artworks

As Suprematism was developed in the Soviet Union, the majority of artists who practiced within the style were Russians. Led by Kazimir Malevich, a select group of artists joined the Suprematist group as they were inspired by the concept of pure abstraction. In our list below, we will be looking at three of the most well-known Russian Suprematism artists to emerge from the movement, along with a few of their most notable paintings.

Kazimir Malevich (1879 – 1935)

Existing as both the founder and central figure of Suprematism, Kazimir Malevich developed the art movement after comprehending the key concepts of Impressionism, Symbolism, Fauvism, and Cubism. These genres led to the development of an increasingly simplified art style that was made up of just pure geometric forms and their relationships to one another.

Through this radical experiment, Malevich produced some truly iconic Suprematism paintings. Out of his works, Black Square (1915), Suprematist Painting, Eight Red Rectangles (1915), Suprematist Composition (1916), and White Square on White (1917 – 1918) exist as his most notable.

Black Square was seen as Malevich’s most radically abstract painting and it quickly became the focus of the entire movement.

The artwork simply depicted a plain black square that was painted onto a white background. As this painting was considered to be the most well-known painting ever created by Malevich, he later claimed that his simple representation of a square on a canvas was his attempt at trying to free art from the dead weight of reality.

Malevich’s Suprematist paintings were considered to be more revolutionary than the work produced by the Cubists and Futurists, as his seemingly two-dimensional works were able to present powerful and layered symbols relating to feeling, time, and space.

He later went on to introduce the illusion of three-dimensionality within his works through more complex shapes, such as fragmented circles and triangles, and a more diverse color palette. In the third phase of the Suprematism movement, Malevich’s experimentation culminated into his White on White artwork, which portrayed a vaguely outlined square that hardly emerged from its background.

Malevich’s artistic style eventually reduced the inclusion of form to almost nothing, which demonstrated his radical transformation within the art world.

Lyubov Popova (1889 – 1924)

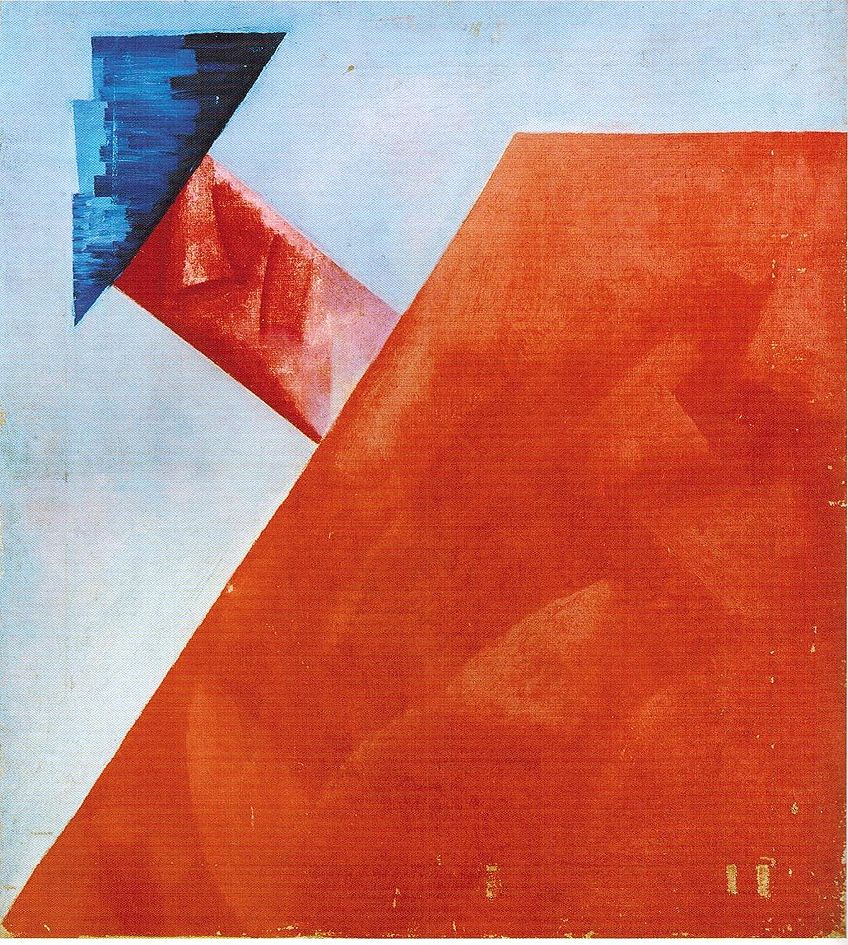

A prominent female artist of the Suprematism movement was Lyubov Popova, who worked at a time when there were relatively few women artists respected by art institutions and the revolution. As an exceptional multimedia artist and designer, Popova was an active Communist during the 1917 Revolution and throughout the years that followed. Some of her most significant Suprematism paintings included Painterly Architectonic (1916) and Untitled, from Six Prints (1917 – 1919).

Displaying a great interest in the concept of dynamism, Popova worked to represent movement in her artworks. She brought this fascination with her when her interests turned to complete abstraction and simplified geometric forms, as she began to create art that was in keeping with the energy and fervor of the revolution.

Like other Suprematist artists, Popova believed that art should reflect the industrial future that was developing, which allowed her to create artworks that imitated the geometry and capability of machinery through abstraction.

Eventually, Popova strayed away from painting in order to follow her belief that revolutionary art should be easily available, feasible, and reproducible. This led to her designing stage sets, publication covers, and textiles, with these mediums demonstrating her passion and enthusiasm for Russian art at that time.

Despite her short life, Popova’s productive career showed that an aesthetic medium could play an important role in revolutionary politics as well.

El Lissitzky (1890 – 1941)

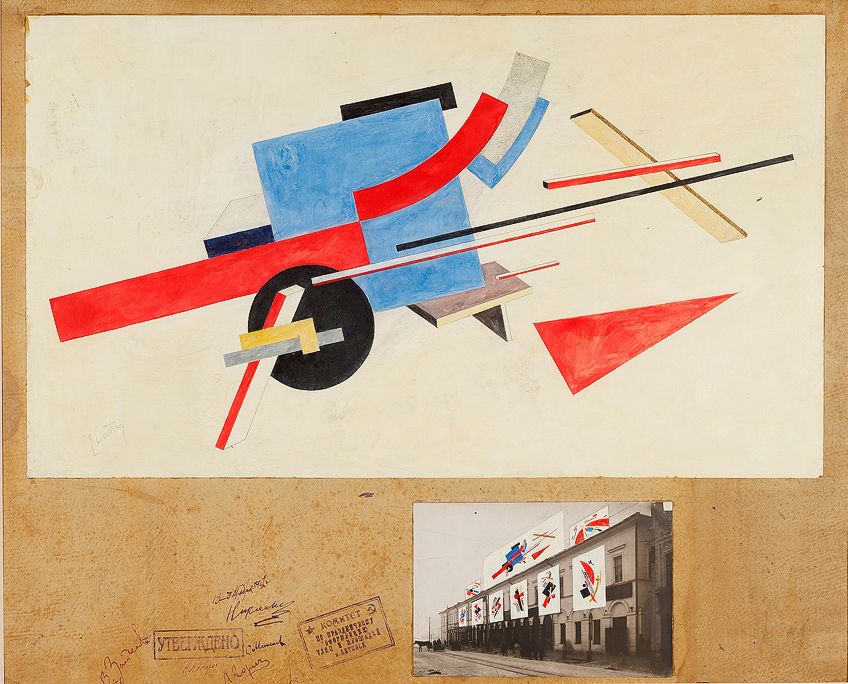

The final artist on our list is El Lissitzky, who molded his career out of using art for social change. While his works were highly abstracted and very theoretical, he was said to have made the very first Suprematist artwork that contained a political message, as he spoke to the prevalent political discourse of Russia at the time. Particularly influenced by the artworks produced by Malevich, Lissitzky went on to develop his own unique version of Suprematism, which he labeled “Proun”.

One of his most radical artworks includes Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919), which demonstrated his use of politics within his works through the title and implication of the message. Another artwork, known as Proun 99 (1925), saw Lissitzky experimenting with three-dimensional environments and two-dimensional shapes, and was titled after his own style of Suprematism.

Working within Suprematism between 1919 and 1925, Lissitzky helped to popularize the movement and its ideas outside of Russia. At an exhibition in Berlin in 1923, Lissitzky was said to have interacted with Dutch artist Theo van Doesburg, which led to a bridge forming between Suprematism and the movements of De Stijl and the Bauhaus.

His Proun artworks also went on to deeply influence the likes of Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Wassily Kandinsky, which transported the ideals of Suprematism considerably.

Following in the footsteps of Malevich, Lissitzky made use of color and basic shapes in the same way. However, what made his artworks stand out from Malevich’s was that he added strong political statements to his basic shapes and colors, which were often unfiltered, bold, and in support of political change and equality. Lissitzky also challenged the traditional conventions of art through his Proun series of paintings, which saw him experimenting with notions relating to space and architecture.

Lissitzky believed that art and life could easily combine, with art being able to deeply affect life when they collided. This led to him stating that graphic arts, such as posters and books, as well as architecture were effective vehicles for communicating certain messages to society.

Lissitzky began to practice across a variety of mediums like graphic design, typography, photography, photomontage, and book design, which allowed him to create quite intelligent works that deeply influenced the later development of modern art.

The Decline and Legacy of Suprematism

As time went on and the Russian Revolution increased in authority, the impact of the Suprematism movement wavered. However, as the early Communists came to power shortly after, they ensured that the influence of Suprematism continued. Despite this, the attitudes of artists had already begun to change and by the late 1920s, Suprematism began to decline in popularity, as the movement and all other avant-garde styles were condemned by Stalinism.

Malevich himself stopped painting in his Suprematist style completely between 1919 and 1927 and instead focused his attention on developing his theoretical writings about the movement. After a long hiatus, Malevich returned to Representational painting and even began to work in the style accepted by Social Realism. Nevertheless, Malevich still found ways to add his own signature style into his new artworks, and even signed a few paintings with a square instead of his name.

As Malevich’s cryptic and abstract concepts stopped the movement from gaining universal appeal, the results of Suprematism have been extensive in the world of abstract art. The influence of Malevich’s key ideas behind Suprematism can be seen in later examples of abstract art, which helped to promote Suprematism outside of Russia.

The impact of this movement also inspired iconic artists such as Lazlo Moholy-Nagy, Wassily Kandinsky, and Piet Mondrian.

Suprematism was later introduced to the West in 1927 by a popular exhibition held in Berlin, which helped spark interest in the movement throughout Europe and the United States. Several of Malevich’s Suprematism paintings were bought by Alfred Barr for the Museum of Modern Art in New York and were included in an exhibition that went on to greatly influence modernism within America.

The legacy of both the Revolution and the emergence of Suprematism can still be seen and felt in the art world today. The paintings and ideals created by Malevich exemplified a very optimistic type of Modernism that aimed to escape the limitations of reality, which is still admired today.

Within Suprematism, the simple square went on to represent the birth of an entirely new and abstracted movement and was dubbed the “face of a new art”. However, as this was met with resistance, Suprematism went on to be continually challenged and mocked by those who did not understand its meaning and purpose. When considering the notions of what Suprematism was attempting to achieve, we can begin to recognize Malevich’s idea of the new type of realism he was trying to create, which was based on simplicity, universality, and purity.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Suprematism – The Art and Artists of the Russian Suprematism Movement.” Art in Context. July 8, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/suprematism/

Meyer, I. (2021, 8 July). Suprematism – The Art and Artists of the Russian Suprematism Movement. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/suprematism/

Meyer, Isabella. “Suprematism – The Art and Artists of the Russian Suprematism Movement.” Art in Context, July 8, 2021. https://artincontext.org/suprematism/.