Italian Renaissance Art – What Was the Italian Renaissance?

The Italian Renaissance period was a revival of the ideals and culture lost during previous years of war, as well as a resurgence in the various social and political differences within Europe during the Medieval age. This revival led to a complete shift in perspectives – quite literally and figuratively – in Italian art and culture. Overall, it was a new time for Europe, and it became a period of history that would live on for ages to come.

Table of Contents

What Was the Italian Renaissance?

Below, we will discuss the origins of the term renaissance, as well as an overview of how this period in Italy emerged from prior historical events like the Medieval ages, which catalyzed the growth and development of this movement.

A “Rebirth”

The Renaissance is said to have started in Italy during the 1300s. It was a revival in arts, architecture, literature, music, culture, technology, science, theology, geography, and politics. The Renaissance was a period of “rebirth”, which found its way throughout numerous countries in Europe.

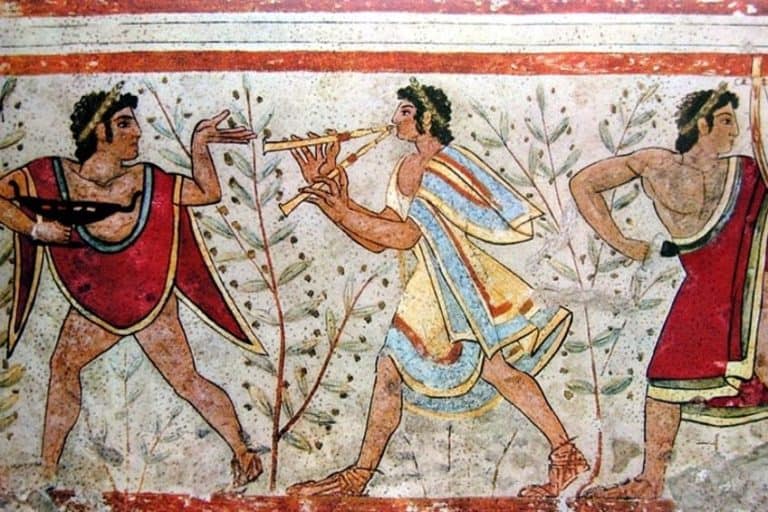

This “rebirth” also sought to reawaken what is referred to as “classical antiquity” from the ancient times of Greek and Rome. The Italian Renaissance was a new discovery of the humanities, and really, of humanity itself.

Italian Renaissance artists focused more on the ideas of humanism and naturalistic portrayals of the world and people around them.

In fact, the word renaissance itself is a French word, but its origins come from the Italian word rinascita, which means “rebirth”. Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), a man of many talents (he was an artist, art theorist, architect, writer, and engineer), first introduced this term to describe this new period of awakening in Italy in his publication Le Vite, meaning “The Lives”.

Le Vite was considered one of the best publications about art history, especially during the Italian art period. It was written in a biographical format about various artists, architects, and sculptors (its longer title is Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori, e architettori, which means “The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects”).

Historical Perspectives About the Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance period is said to have started during the 1300s (the 14th Century). This was during the Medieval period in Italy’s history, also called the Middle Ages, which is said to have occurred during the 400s to late 1400s in Europe. The Middle Ages can be looked at from the Early Middle Age, High Middle Age, and Late Middle Age. Each stage had its own challenges politically, environmentally, and economically, which impacted the whole of Europe and the world.

The Middle Ages is also known as the “Dark Ages” because of widespread wars, pandemics like the Black Death, and famines as a result of climate changes and economic upheavals. There were many significant events during the Middle Ages. The Fall of the Roman Empire (c. 476 CE) and the overthrow of Roman Emperor Romulus Augustulus in the west led to the start of the Middle Ages, including the rise of Christianity and Catholicism and widespread invasions and migrations of people across the countries.

From the fall of the Roman Empire to the rise of the Middle Ages, the Renaissance became a period of transition into a lighter age of existence.

Early Italian Renaissance art started in Florence, Italy, due to the movement’s roots in the Roman Empire as well as the wealthy families willing to support the arts. There were two important contributing factors during the Renaissance period, namely, the movement of philosophical ideals called Humanism, and the influence of wealthy families, specifically the Medici family.

Humanism

Humanism started during the 1300s, and is referred to as an “intellectual movement” of the time. It was deeply rooted in philosophical ideas around the importance of man and his place in society. This opposed the Medieval ideals that focused more on the importance of the spiritual and divine – it focused on the role of the centrality of the above two figures, namely man and God.

Renaissance Humanism explored and studied different schools of thought, such as grammar, history, moral philosophy, poetry, and rhetoric – this was known as the studia humanitatis. These topics of study were considered acceptable towards the study of classical values. This new form of education was also open not only to elites but the public as well, including new humanist libraries.

The Humanists placed man as the central deciding figure of personal power. In other words, man was at the heart of new intellectual pursuits like logic, aesthetics, classical principles, the arts, and sciences like mathematics. The rule of the Church, which was such a large part of European society, was redefined in terms of its efficacy in determining what man should do or who man should be.

The term “Renaissance Man” became a popular description for people with this newfound power.

There was a large resurgence and revisiting of Greek and Latin literature on various subjects during the beginning stages of the Renaissance. Many of these classical texts informed the new approaches taken in painting, architecture, and the principles of perspective and beauty.

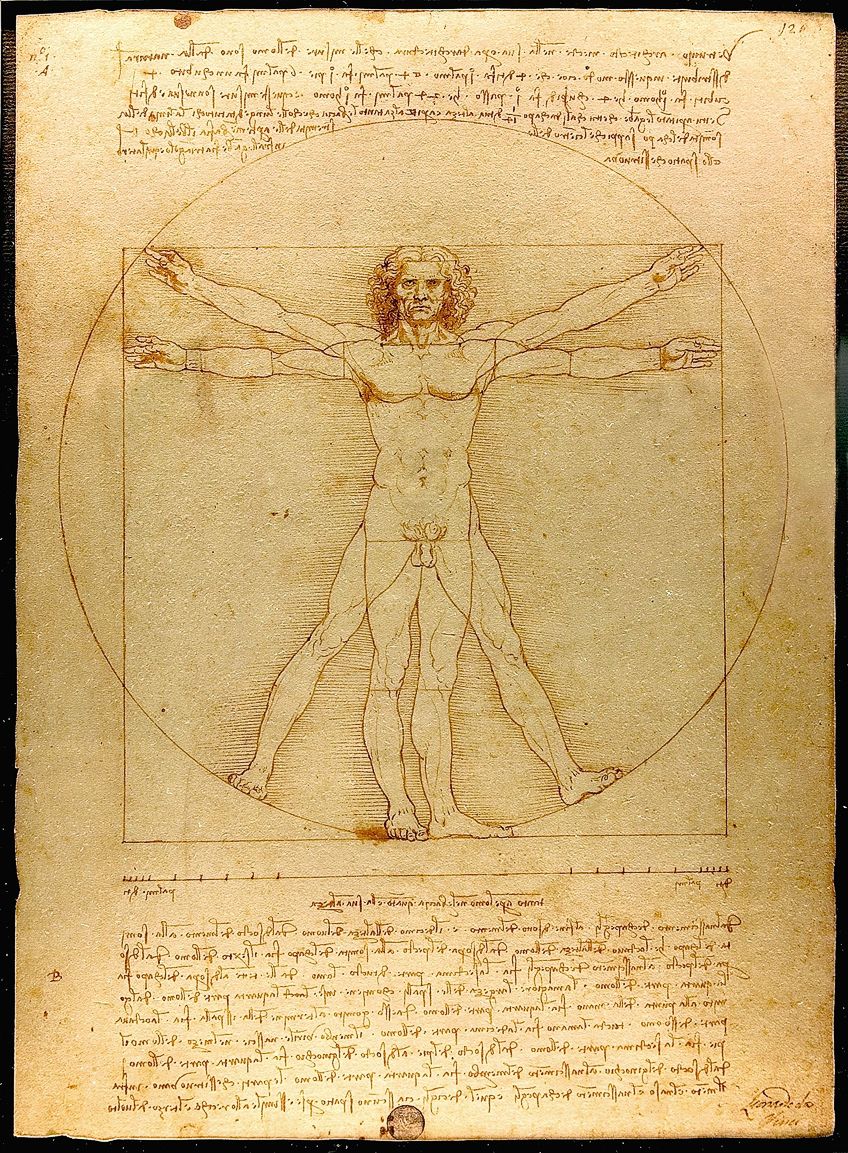

An example of a classical text was the work done by Vitruvius, who was a Roman architect. Vitruvius wrote about his ideals during the 1st Century BC, namely his “Vitruvian Triad”, which was based on the principles of beauty, unity, and stability. This placed a focus on applying mathematical proportions to the faculties of arts like painting, architecture, and especially the proportions of the human body.

Petrarch (1304-1374), the well-known poet, was known as the “father of the Renaissance” as he was the leading figure who catalyzed the Humanist movement. Although the Catholic Church had a large role of power during this time, and Petrarch was a Catholic himself, he nonetheless believed that humans had been given power by God to realize their potential – this form of thought was at the heart of Humanism.

It is important to note that Petrarch found the writings of early Roman, Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC), which he translated.

Plato (428/427 BCE-348/347 BCE), a Greek philosopher, was another influential figure for the Renaissance Humanists. Plato’s philosophies were introduced at the Council of Florence during the years 1438 to 1439 by George Gemistus Plethon, or Pletho (c. 1355-1450/1452), who was a philosopher during the Byzantine era. The importance of this was that it influenced Cosimo de’ Medici, who was a significant figure of economic power in Florence.

It is believed that Cosimo de’ Medici sponsored the Accademia Platonica, “Platonic Academy”, where Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499), an Italian Catholic priest, translated Plato’s works. However, this has been disproved by several scholarly sources, who have stated that Ficino’s writings were not translated correctly. Ficino called Plethon the “the second Plato” due to his influence in bringing Plato’s works to the west.

The Medici Family

This brings us to the Medici family, or House of Medici, important influencers on art, economy, politics, and general Italian society during the Renaissance. This took place mostly in Florence, which became the capital for following the ideas from the Classical era – it was also known as the “New Athens”.

During the 1200s, the Medici family began worked in banking and commerce in Florence after they moved from their home in Tuscany. The Medici Bank was started by Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici (c. 1360-1429), who was the father of Cosimo de’ Medici (1389–1464), who ruled Florence.

What is important to know about the Medici family is their patronage of the art world. Cosimo de’ Medici commissioned many artists to produce paintings and also started the public library in Florence, among other endeavors that supported the development of the arts in Florence. Cosimo de’ Medici’s love of art, and collecting it, is often elaborated by his quote:

“All those things have given me the greatest satisfaction and contentment because they are not only for the honor of God, but are likewise for my own remembrance. For fifty years, I have done nothing else but earn money and spend money, and it became clear that spending money gives me greater pleasure than earning it”.

Italian Renaissance Characteristics

There are a number of themes and motifs found within many Renaissance paintings, as well as certain techniques used by many of the artists of the time. It is by locating these characteristics that one is able to identify a Renaissance piece of art.

Naturalism and Realism

Naturalism in Italian art depicted subject matter in a more realistic manner. In other words, it reflected the external world and people as they appeared. This was also characteristic of Greek and Roman art, and something that the Italian Renaissance artists sought to emulate. Another word for this is termed Realism.

The element of realism was at its best evident in how artists chose to depict anatomy, whether in paintings or sculpture. Many artists studied the human figure, in fact, to gain a better understanding of how the human body worked and looked. Some artists like Leonardo da Vinci even studied real corpses.

Contrapposto

There are various painting techniques that artists started utilizing to increase the effect of realism in human figures. One example is contrapposto, which means “counterpoise” in Italian. Figures would be placed with one side of the body leaning dominantly on one foot while the other side of the body, feet, and hips, would appear lower – otherwise understood as the center of gravity being heavier on one side than the other. This technique of portraying a figure made it appear more life-like and dynamic. Additionally, the figure would appear to convey more emotion due to the indication of body language.

Chiaroscuro

Another artistic technique used was the contrast between light and dark, otherwise known as chiaroscuro, an Italian word meaning “light-dark”. Artists used this technique to convey depth and dramatic emphasis in their compositions. This would also create a sense of realism by depicting the way light and shadow would appear in the real environment, thus giving the whole composition a three-dimensionality, which was a considerable change from the two-dimensional spaces from earlier art periods.

Linear Perspective (One-Point Perspective)

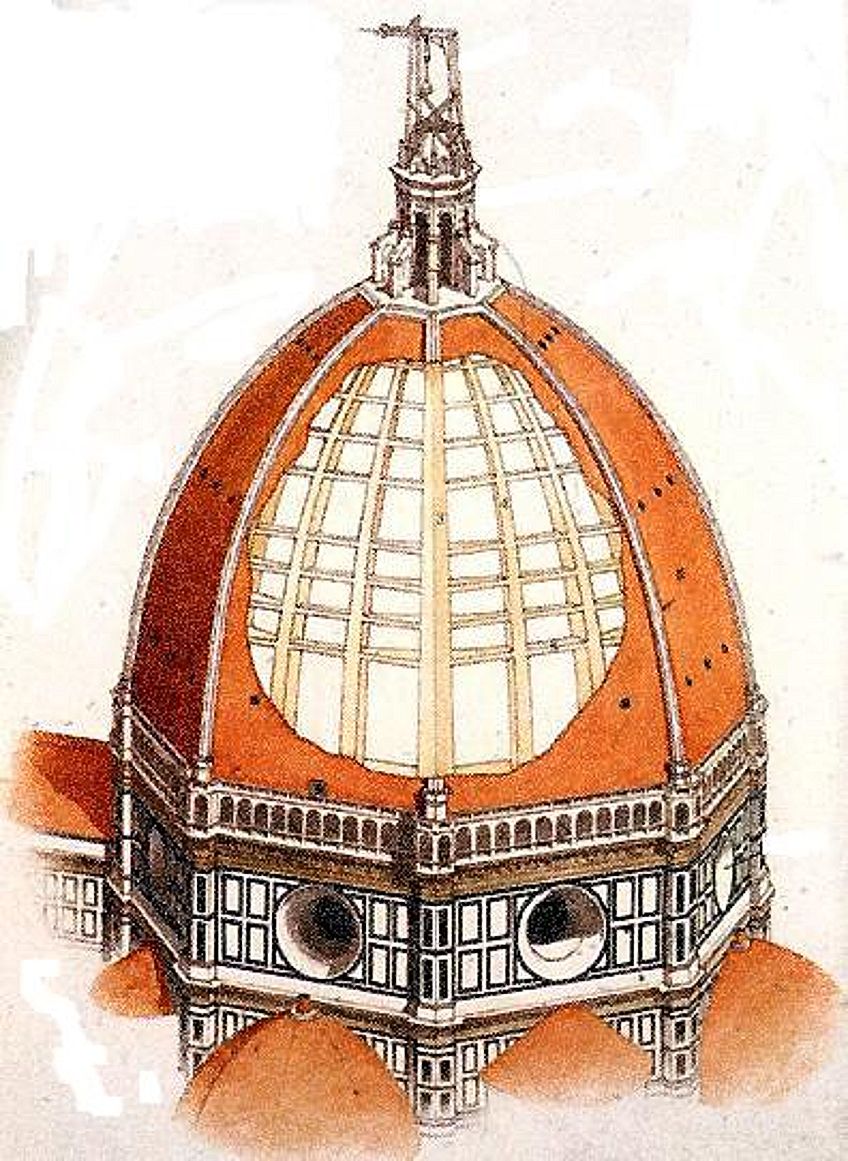

The use of linear perspective, or one-point perspective, also enhanced the sense of realism in paintings giving it a three-dimensionality. This technique was first pioneered by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377 – 1446), an Italian architect and designer. He was also considered as one of the “fathers” of the Renaissance period because of his pioneering discoveries in design and architecture from a scientific and mathematical point of view.

It is believed that Brunelleschi also studied ancient Roman architectural structures and sculptures. The one-point perspective focused on a chosen single viewpoint of lines converging on the horizon. This was different from how the multiple viewpoints were shown in paintings during the Middle Ages.

The dome of the Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore, or “Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower” (1377-1446), is a well-known structure in Florence engineered by Brunelleschi. The dome moved away from the well-known Flying Buttresses used during the Medieval Ages’ Gothic Architecture. It was created using various self-sustaining reinforcements with a large lantern at the top tip of the dome, otherwise known as the cupola.

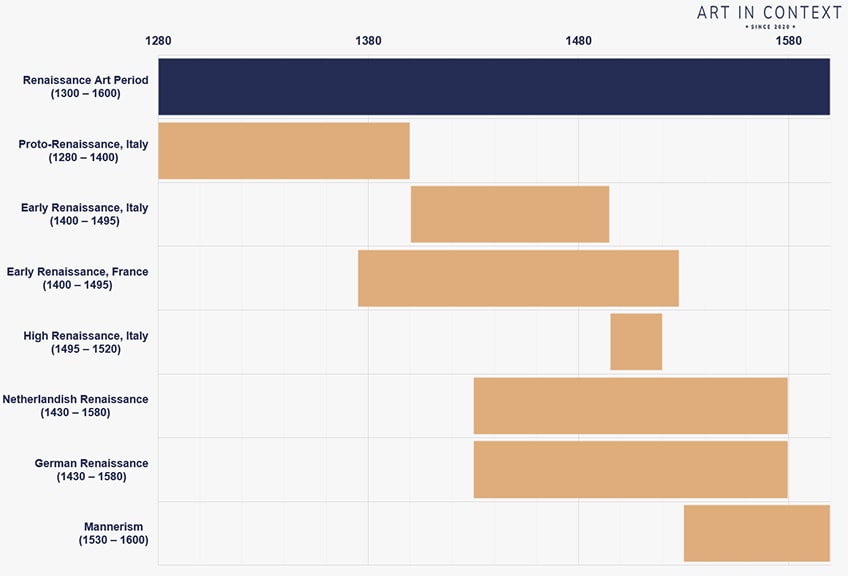

Distinguishable Italian Art Periods and Artists

The Italian Renaissance can be easier understood by looking at it in different periods. While some divide it into four periods, the fourth being Mannerism, here we will look at the three primary divisions that took place related to the Italian Renaissance periods. Below, we will discuss the timeframes and prominent artists.

Proto-Renaissance (Trecento)

The Proto-Renaissance period occurred during the 1300s, and is otherwise referred to as Trecento in Italian, meaning “300”. The exact years fall between 1300 and 1425. The Proto-Renaissance began as the first transition into the Renaissance period. What started characterizing this period of art (painting, sculpture, and architecture) were the naturalistic portrayals of subjects.

Giotto di Bondone (c. 1267 – 1337)

One of the pioneering artists during the Proto-Renaissance period was Giotto di Bondone, born in Florence, Italy. He was a painter and architect and considered to be one the best painters of his time. He was an apprentice to the artist Bencivieni (Cenni) di Pepo, also known as Cimabue (c. 1240-1302) who was known for exploring the very first elements of naturalism during the Byzantine period before the Renaissance. Giotto, however, is reported by scholarly sources to have overtaken Cimabue in his skill to portray nature around him with an increased sense of realism and a keen eye for detail.

He is known as emphasizing humanity in his paintings, enhanced by his use of perspective, emotive details in his figures, and the lavish costumes worn by them.

Giotto’s subject matter was of Christian narratives and figures, and he was commissioned by the Church for several frescoes, namely, Isaac Blessing Jacob (c. 1290-1295), which is in the Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi. Giotto painted the biblical story from the Old Testament depicting Jacob giving his father food with Rebekah, Jacob’s mother, standing next to Jacob and Isaac.

A key work by Giotto is Lamentation(The Mourning of Christ) (1305), which is a fresco done for the Scrovegni Chapel (Arena Chapel) located in Padua, which is a city in Italy. This fresco is not a stand-alone painting, it is part of a series of frescoes that Giotto painted for the chapel about Christ and Mother Mary’s lives.

Lamentation depicts the events when Christ was taken from the cross, and we can see the surrounding figures grieving over his death as Mother Mary holds him in her arms. We can see around 10 figures in the foreground receding into more in the background. Above the crowd are 10 grieving angels also twisting in apparent sadness.

What makes this painting unique and a grand example of the beginnings of the Early Italian Renaissance art is how Giotto portrayed detail in the faces of the surrounding figures, as well as their arms and hands clearly visible in their gesticulation. The sloping of the rock on the right almost moves down to create more emphasis on Christ on the floor.

The above elements all create a sense of perspective and depth to the painting, including the receding figures to the left of the background. It is almost as if Giotto is connecting heaven and earth with the sloping rock in the middle, which creates more realism and a sense of connectedness with the divine.

Ognissanti Madonna (c. 1300-1306) is another important work by Giotto depicting the naturalistic style characteristic of the Renaissance period. It depicts Madonna with the Christ Child seated on her left leg, holding his right hand up in a gesture of blessing. The two central figures, Madonna and the Christ Child are depicted considerably larger than the surrounding figures.

The throne is also depicted larger with two angels kneeling by its steps. We also notice how all the surrounding angelic figures are looking at the Madonna with Child, which indicates how the artist uses perspective and spatial distance to lead the viewer to the focal point.

Furthermore, Giotto painted the Madonna and Child more realistically by the way their fine clothing, almost see-through, folds around their body, indicating the flesh underneath. This shows us the human aspects of the divine, making it easier to relate to these hallowed figures.

Cimabue may have painted the same scene before Giotto, however, what makes Giotto’s painting of the Madonna and Child unique is his realism and detailed depiction of not only the human figures and their expressions, but also the architectural detail of the throne.

Giotto inspired many more sculptors and painters during the Early Renaissance period because of the above stylistic innovations.

Early Renaissance (Quattrocento)

The Early Renaissance period occurred during the 1400s, and is also referred to as Quattrocento, which means “400” in Italian. The exact years can fall between 1425 and 1495. When we look at paintings from this period, we notice how artists started to portray a keener eye to detail in their subject matter.

Influenced by the forerunners of Renaissance paintings like Cimabue and Giotto, artists focused on the realistic depiction of human figures and anatomical correctness. Artists also utilized more intentional perspectives of figures and buildings and their placements within the space around them. This mastery of the mathematically aligned perspective and placement of various religious subject matter is particularly evident in Pierro della Francesca’s work, such as The Baptism of Christ (c. 1448-1450) and The Flagellation of Christ (c. 1455).

Although the Early Renaissance artists still portrayed scenes from the Bible and narratives around what the Church valued, they started to incorporate mythological subject matter as well as everyday occurrences and people, which shifted the focus off of the holy and onto the ordinary – ultimately making art more relatable for the everyone.

Alongside new subject matter, we will also notice how artists depicted more emotion and human-like qualities in their subject matter. This reinforced the notion of Humanism that many artists strove to emphasize, again bridging the divide between the divine and man, placing man as the central figure experiencing life, nature, and God.

Some of the leading painters and sculptors during this period were Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Simone, mostly known as Masaccio (1401-1428), and Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi, named Donatello (c. 1386-1466). Masaccio is highly regarded as one of the pioneers of Renaissance painting, especially for his use of linear perspective and creating true-to-nature depictions of his human figures. He was influenced by other prominent artists like Brunelleschi and Donatello.

Donatello (c. 1386 – 1466)

Born in Florence, Donatello became one of the best sculptors during this period of the Renaissance. He was exposed to a rich education growing up and his education as an artist started with tutelage from a goldsmith. He also worked as a goldsmith while he pursued his artistic career. He was close friends with Brunelleschi and traveled with him to various Greek and Roman ruins where he found considerable inspiration for his work as an artist.

What set Donatello apart as one of the forerunners of Renaissance sculpture was the way in which he utilized perspective in his sculptures. He also used various subject matters, ranging from Mary Magdalene as we see in his hyper-realistic wooden carved statue, The Penitent Magdalene (c. 1453) to political figures as we see in the Bust of Niccolo da Uzzano (c. 1433).

Donatello introduced new techniques in his sculptures, namely referred to as bas-relief, which is also called low relief. This depicted a sense of three-dimensionality due to the part of the sculpture being slightly raised from the surface, otherwise characterized as having “shallow depth”. This is evident in his earlier relief titled, St. George Killing the Dragon (1416-1417), which makes up the base of his marble statue, St. George (1415-1417).

David (1440-1443) is one of the more famous sculpted masterpieces by Donatello. Made of bronze, this depicts David standing at five feet in height wearing a hat and boots, a sword in his right hand, and the helmet of Goliath partly between his legs. Donatello revolutionized the image of David during this time by depicting him as a young man in the nude, which was the first nude sculpture created since the Greek and Roman period.

Furthermore, this sculpture denotes a sense of gentleness and femininity in the depiction of David, and many scholarly sources discuss Donatello’s reason for portraying the biblical figure in this manner. An important point to note about this sculpture is that it was made as a freestanding statue and not part of an architectural structure. The figure also stands in the characteristic contrapposto pose, making him more life-like and relatable as a human being instead of a biblical character removed from the everyday experiences of the people.

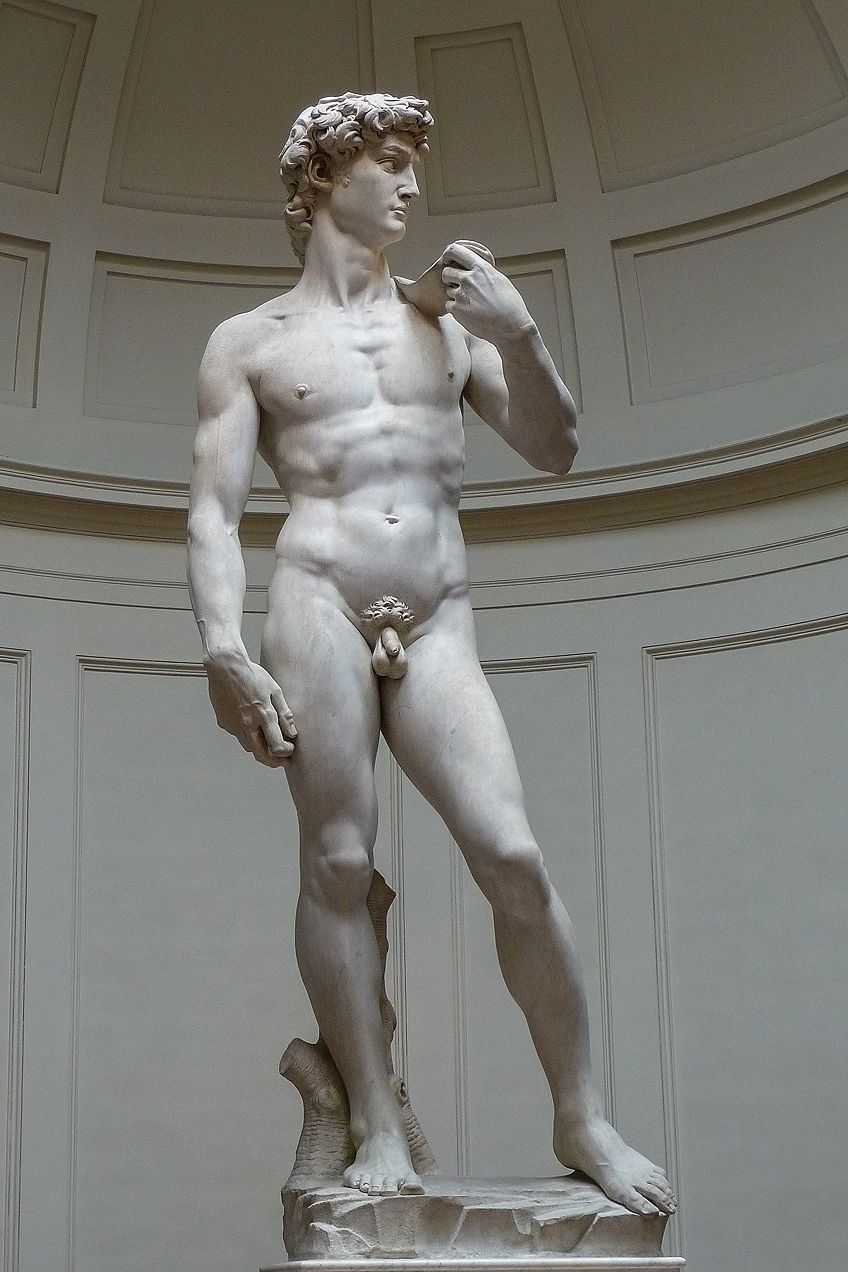

We will see this character revisited in Michelangelo’s similarly titled statue during the later Renaissance periods.

Masaccio (1401 – 1428)

Masaccio was born in the Arezzo province in Tuscany and was considered the first Early Renaissance painters to utilize linear perspective. Influenced by how the architect Brunelleschi utilized perspective, Masaccio started to use these techniques in his paintings, which revolutionized the way artists composed paintings from the two-dimensional depictions of the past. He also used other techniques like chiaroscuro to emphasize depth and three-dimensionality, including achieving a deeper realism in his paintings.

Masaccio’s San Giovenale Triptych (1422) is an early work from the artist. The Vanni Castellani family commissioned this work. It depicts religious scenes of the Virgin Mary with the Christ Child at the center, with two saints on both the left and right panels. From inscriptions below the triptych, it is indicated that the Saints Bartholomew and Blaise are on the left, and Saints Antony and Juvenal are on the right.

We also notice how Masaccio introduces an intentional perspective within the composition by the throne receding in the background in contrast to the figures appearing larger in the foreground. One of his later works, Payment of the Tribute Money (1425 – 1427), epitomizes his success with using linear perspective and more mathematically correct placements of his figures to indicate a sense of unity and harmony.

This work was done as a fresco for the Brancacci Chapel of Santa Maria del Carmine located in Florence. It depicts what is referred to as a “continuous narrative” – in other words, there are three stories portrayed in one fresco painting. It tells the story of Christ and St. Peter paying the tax collector.

We will notice how the first part of the narrative is portrayed in the center of the fresco, depicting Christ with his apostles in conversation with the tax collector, who has his back to the viewer. We see how Christ points his finger to the left with Peter on his left, also pointing his finger to the left.

This almost moves us to the left side of the fresco, the second part of the narrative, where we see Peter bending down by the river getting money from the mouth of a fish. This narrative is easily understood from the Gospel of Matthew about the account of Jesus paying tax at the fishing village called Capernaum. During the conversation Jesus says to Peter, as accounted in the bible, “Take the first fish you catch; open its mouth and you will find a four drachma coin. Take it and give it to them for my tax and yours”.

When we look at the right side, the third part of the narrative of the fresco, we notice Peter again, but this time it is only himself and the tax collector, who is receiving the tax money taken from the fish’s mouth. The way in which the figures are gesticulating and talking with one another, as well as the detail on their facial expressions, gives the painting its realism.

We also see the three-dimensionality indicated from the way in which the mountains recede in the background, including the tax collector with his back to us. Furthermore, Masaccio also included light and dark, evident in the shadows created by the standing figures and the light coming from a specific side of the painting.

The fresco almost invites us into its space, which is wholly different from the flatness and two-dimensionality of more Gothic art prior to this period.

Sandro Botticelli (c. 1445 – 1510)

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi (c. 1445-1510), otherwise known simply as Sandro Botticelli, was born in Florence and was an apprentice to the well-known painter Fra Filippo Lippi (c. 1406-1469) during his early years. Botticelli is extremely well-known; he was also one of the first artists to create paintings that not only depicted the use of perspective and anatomical naturalism, but also combined aesthetics and beauty.

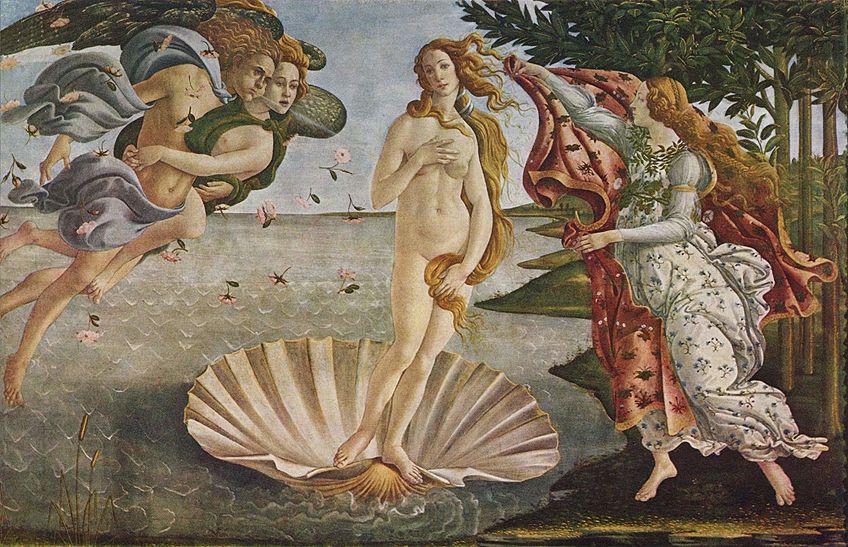

He did not only paint religious subject matter, but also portrayed many mythological figures and characters, specifically Venus, the Roman Goddess. We notice this in his popular paintings, housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, titled Primavera (1477-1482) and The Birth of Venus (1485-1486).

Both paintings are of mythological subjects. Primavera, which means “Spring” in Italian, depicts Venus as the central figure, surrounded by various other mythological characters. This painting was the first European painting with a subject matter unrelated to Christian narratives.

The Birth of Venus depicts the goddess Venus again as the central figure, only here she stands on a large shell coming in from the ocean onto the beach. She is met by a female figure to the right and the god Zephyr to the left, blowing her onto the shore.

Botticelli painted this as almost life-size, which further created a dramatic emphasis upon viewing it. Venus is also portrayed as nude, only slightly covering herself with her long hair – this was another revolutionary depiction of the female form.

Venus is not portrayed with the anatomical realism we so often see in paintings from this period, which indicates how Botticelli shifted between symbolism and realism when painting his figures. He also painted for the sheer pleasure of depicting beauty.

High Renaissance (Cinquecento)

The High Renaissance period took place during the 1500s and is referred to as Cinquecento, which means “500” in Italian. The exact years can fall between 1495 – 1520. While this period continued using the new advancements in methods of perspective and humanism seen from the earlier Renaissance periods, it is considered the peak of the Renaissance.

While Florence was the capital for the start of the Renaissance period, the High Renaissance took place predominantly in Rome due to the push from Pope Julius II during his reign between the years 1503 and 1513. He sought to have all the cultural and artistic works in Rome and not in Florence, with this he commissioned many of the well-known artists of the time to paint for him.

New innovations and artistic techniques like sfumato and quadratura were discovered during the High Renaissance. Artists also started using oil paint, which was a new medium for painting compared to the earlier periods. It also gave a richer color to the subject matter portrayed.

We will notice a higher level of refinement of principles like perspective, how figures are positioned, form, and color in the paintings from this period.

While there were many artists (painters, sculptors, and architects) during the High Renaissance, we will recognize some names with more familiarity than others, for example, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Michelangelo (1475-1564), and Raphael (1483-1520). The above “trio” created a vast array of artworks and inventions that still live on to this day.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519)

Leonardo da Vinci was a master of his time, he was not only adept as an artist, but he was also an inventor, scientist, engineer, and more. Many of his drawings indicate more modern mechanics like the helicopter. He was born in Tuscany and started his career as an artist at age 14. He was taught by another great artist and goldsmith called Andrea del Verrocchio (1435 – 1488) and at a later age worked at Verrocchio’s school in Florence.

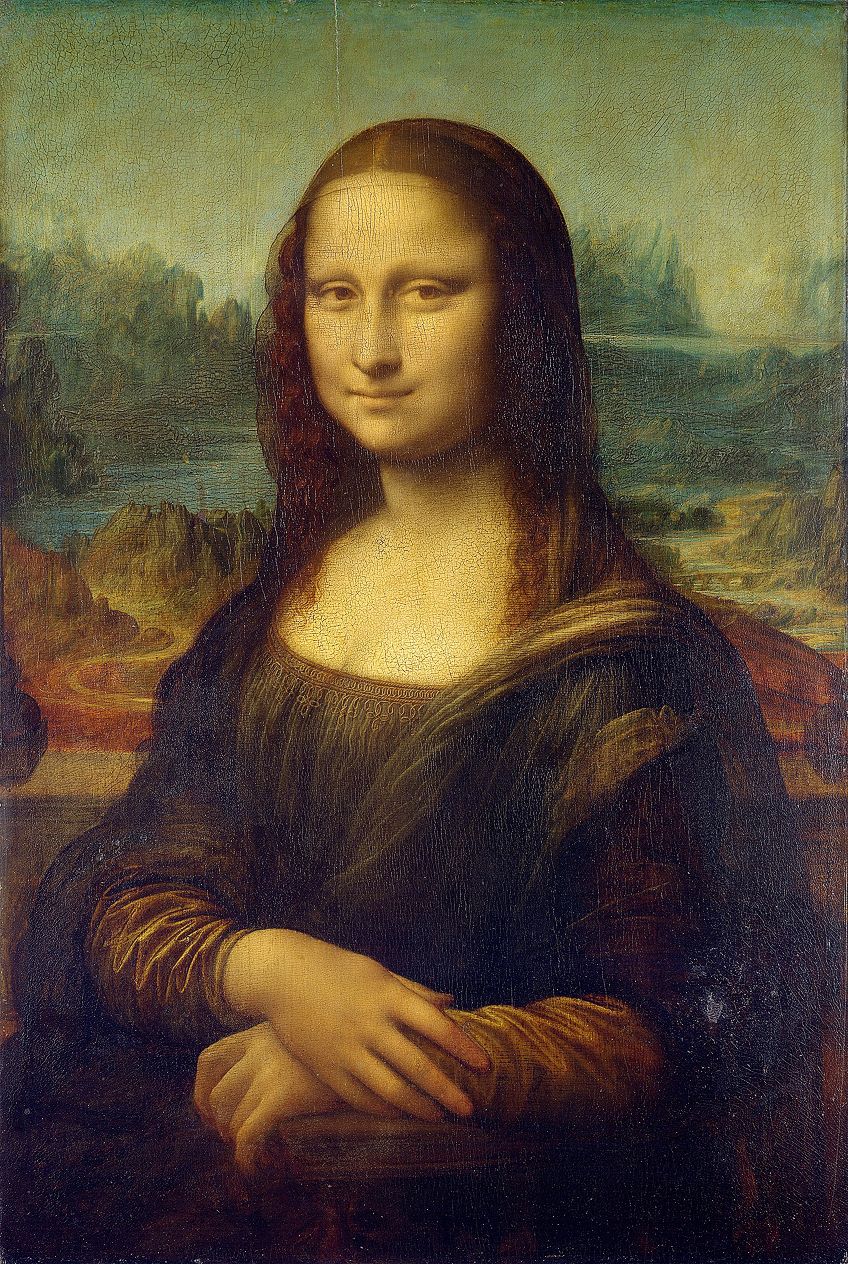

Some of da Vinci’s famous artworks include Virgin of the Rocks (1483-1486), The Vitruvian Man (c. 1485), The Last Supper (1498), Salvatore Mundi (c. 1500), and the Mona Lisa (c. 1503). We will notice that with most of da Vinci’s paintings and drawings, he depicted a heightened sense of realism and naturalism in his subjects. He also pioneered the sfumato technique, which is an Italian word meaning “smoked” due to the smoky effect caused by layers of paint and color gently layered and blended over one another.

When we look at the Mona Lisa, otherwise also known as La Gioconda, da Vinci used various techniques to emphasize the realism we are so used to seeing from Italian Renaissance painters. The use of sfumato gives an additional softness to the composition. Da Vinci also utilized chiaroscuro as we notice in the background, creating more depth.

Michelangelo (1475 – 1564)

Michelangelo was born in Tuscany and moved to Florence from a young age as an apprentice under the Medici family. His artistic career evolved over time, where he eventually also moved to Rome. He was another prodigy of his time and a rival of Leonardo da Vinci. He was a sculptor and painter depicting high levels of realism in his sculptures and artworks.

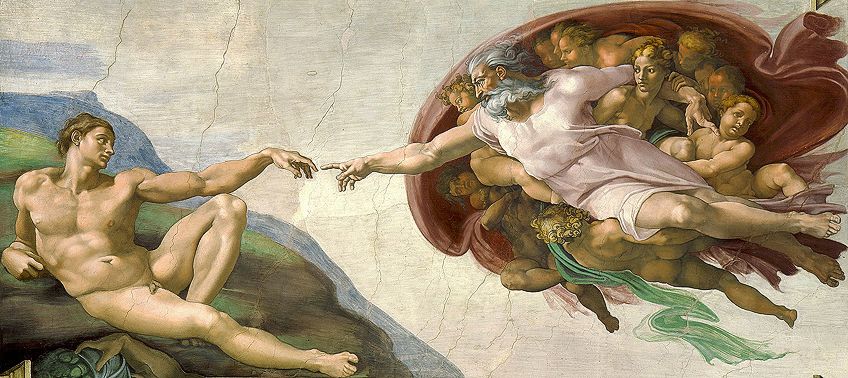

Some of Michelangelo’s famous artworks include the well-known Sistine Chapel ceiling where we will find The Creation of Adam (1508-1512), which depicts Adam on the left and God on the right, both as strong, muscular men. This portrayal of both man and God showed Michelangelo’s expression of the Humanist philosophy, one of the primary Italian Renaissance characteristics.

We also notice this keen attention to detail in his sculptures, for example, his earlier statue called Bacchus (1496-1497), the Pietà (1498-1499), and the popular David (1501-1504). The Pietà was carved out of one block of marble within a timeframe of two years. It depicts the Mother Mary holding the dead body of Jesus Christ. What is different from other depictions of this religious scene is the calmness Michelangelo chose to portray. Mother Mary is portrayed as a younger female and her facial expression has a tenderness that enhances the emotional aspects of the sculpture when viewing it.

Michelangelo also constructed the sculpture according to a pyramid’s shape – the top tip starts at Mother Mary’s head and the widening from her robes creates the downward movement, and sides of the pyramid, and the foundation is indicated by the base the figures are on.

When we look at Michelangelo’s statue, David, the artist portrayed the biblical figure in the nude as a strong young man. We can see how he confidently stands in a contrapposto stance, one of the typical Italian Renaissance characteristics. What is particularly evident from this statue is Michelangelo’s proficient attention and understanding of the human form and anatomy carved in marble. Although there have been many sculptors during the Renaissance who carved the character of David, Michelangelo’s rendition has stood strong above all the others.

Raphael (1483 – 1520)

Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino) was another master of the Renaissance period and rival to Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. He grew up in Urbino and started his artistic career from childhood taught by his father who was also a painter. He eventually moved to Florence because of various artistic endeavors and commissions. Artistic techniques used by Leonardo da Vinci influenced Raphael, namely sfumato and chiaroscuro.

What set Raphael apart from other Renaissance artists was the way he created his own style, which while still based on the classical principles of the time, also depicted a sense of beauty and grandeur, notably in his use of vibrant colors.

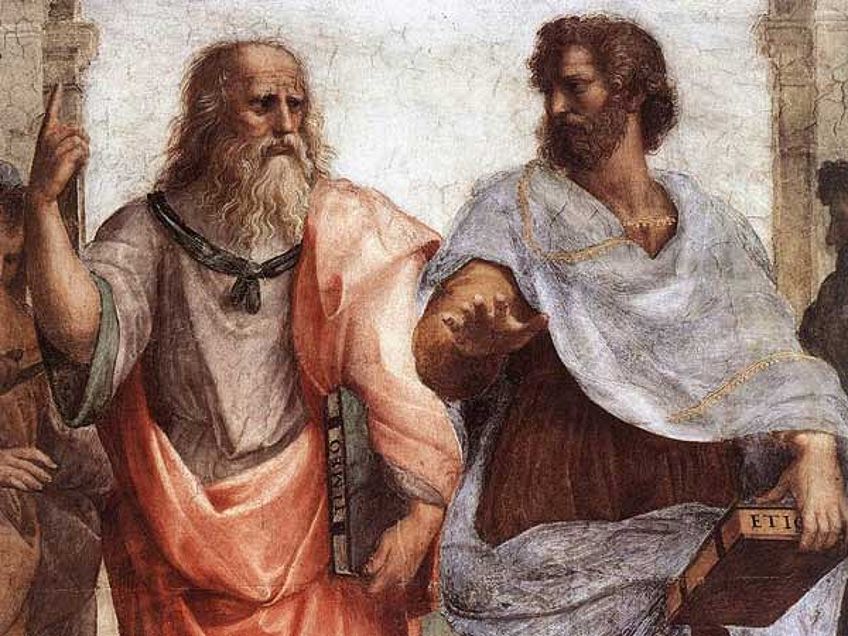

Some of Raphael’s famous artworks include two frescoes, namely, Disputation of the Holy Sacrament (1510), and The School of Athens (1509 – 1511), both painted in the Stanza della Segnatura, which is one of four rooms with frescoes painted by Raphael in the Apostolic Palace in Vatican City – these rooms are also known as the “Raphael Rooms”.

The School of Athens is an iconic work by Raphael, it depicts a group of philosophers standing in a great hall. As the name suggests, these are philosophers from the Classical era. In the center are Plato and Aristotle, with various other renowned figures around them like Pythagoras, Ptolemy, and others.

This fresco is an ideal example of the Italian Renaissance characteristics because of the use of linear perspective and architectural structures creating depth and three-dimensionality. Raphael depicts light and dark in a way where it creates a further three-dimensionality, specifically noticeable from the light entering the building from the background, with a hint of blue clouds visible through the windows.

We also notice a depth of architectural and structural skill from the artist in the surrounding building, arches, and vaulted ceiling. The large arc in the foreground creates a frame-like effect, and it is as if the stage is set, and we are a part of the scene of contemplative and arguing philosophers. Additionally, Raphael did not focus on any one area with a richer color than the other, making the composition easier to witness and unifying all the elements.

Renaissance Beyond Italy and Into the Future

While Italy was the cultural hub for the development of the Renaissance, it undoubtedly spread to other European countries with prominent artists like German Albrecht Dürer and the Dutch / Flemish Renaissance painter Pieter Bruegel. Furthermore, the Venetian School was established in Venice with prominent artists like Titian who influenced artists from later art movements like the Baroque.

The Italian Renaissance period reached an end around 1527 due to many factors like war, specifically the Fall of Rome. The period that came after the Renaissance was called Mannerism, which started around 1520 in Rome and Florence. Mannerism was another branch of Italian art that sought to move away from the classical and naturalistic ideals established by the Italian Renaissance artists – art became more symbolic and figurative.

It is no doubt that the Italian Renaissance as a historical period and an Italian art period left an imprint on the cultural footprints for centuries to come. With new discoveries and inventions across almost all the humanities and intellectual faculties, it was the epitome of a “rebirth” as the name suggests. Furthermore, Italian Renaissance artists set the stage and standards of art in the future, as we still see the masterpieces of antiquity emblazoned in our contemporary pop culture – the “Renaissance Man” lives on.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was the Italian Renaissance?

The Italian Renaissance was a period in European history that made a dynamic transition from the Medieval period. It was a period of “rebirth”, which is also the definition of the term Renaissance. It ushered in a new way of seeing life, man, and God. It was a cultural movement that incorporated all the disciplines like art, science, religion, geography, astronomy, architecture, literature, music, and more. It sought to reestablish the classical ideals that were forgotten from the Greek and Roman periods.

When Did the Italian Renaissance Start?

The Renaissance started during the 14th century and lasted for several decades. Italian Renaissance art is categorized into three periods, namely the Proto-Renaissance period (1300s), the Early Renaissance period (1400s), and the High Renaissance (1500s).

What Characterized the Italian Renaissance?

The Italian Renaissance characteristics were primarily centered on new perspectives from discoveries made in the arts and sciences. Humanism became one of the main philosophies, placing man at the center and redefining the relationship with the Divine. This was especially noticed in how art became more humanized and naturalistic, reverting to the classical ideals of perspective and proportion in how human figures were portrayed.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Italian Renaissance Art – What Was the Italian Renaissance?.” Art in Context. April 30, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/italian-renaissance-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 30 April). Italian Renaissance Art – What Was the Italian Renaissance?. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/italian-renaissance-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Italian Renaissance Art – What Was the Italian Renaissance?.” Art in Context, April 30, 2021. https://artincontext.org/italian-renaissance-art/.