Lithography – Understanding the Art of Lithography Printmaking

What is lithography art? The immiscibility of oil and water is used in the lithography process. Ink is transferred to a grease-treated picture on a smooth printing plate with lithographic printmaking; vacant spaces, which contain moisture, reject the ink. From there the lithography artists – or lithographers can print it onto paper or a roller.

Table of Contents

What Is Lithography Art?

Lithography printmaking is a planographic technique that was predicated on the immiscibility of water and oil at the time. The printing is done on a smooth-surfaced stone or metal plate. It was devised in 1796 by Alois Senefelder, a German playwright, and performer, and was first used primarily for orchestral music and maps. Text or images can be printed using lithography on either paper or other materials.

A lithograph is a lithographic print; however, the name is exclusively applied to fine art prints and a few other, largely older forms of printed materials, not to those produced by current commercial lithography.

Initially, the picture to be produced was drawn onto the surface of a smoothened and flattened limestone plate with a fatty material such as wax, grease, or oil. The stone was subsequently treated with a mild acid and gum arabic combination, which made the sections of the stone’s surface that weren’t coated by grease more hydrophilic. The stone was wet before printing. Only the gum-treated areas absorbed the water, making them even more oil-repellent.

After that, oil-based ink was used, which would only adhere to the original sketch. Finally, the ink would be transferred to a blank sheet of paper, resulting in a printed page. Fine art printing still uses this ancient method. The design is copied or generated as a structured polymer coating bonded to a pliable plastic or metal plate in current commercial lithography. The printing plates, whether made of metal or stone, can be made using a photographic technique known as photolithography.

In offset printing lithography, ink is transmitted from the lithography plate to the paper via a rubber cylinder or plate, instead of straight contact. This method keeps the paper dry and enables completely automated high-speed processing.

For medium- and high-volume printing, it has largely superseded conventional lithography printmaking: since the 1960s, most books and periodicals, especially those containing color illustrations, have been produced with offset lithography from photographic images formed from metal plates.

The Principle of the Lithography Process

To generate an image, lithography employs basic chemical processes. The positive half of a picture, for example, is a water-repelling material, but the negative image is water-retaining. When a suitable printing ink and water combination is applied to the plate, the ink adheres to the positive image while the water cleans the negative picture. This enables the use of a flat print plate, allowing for far longer and more accurate print runs than previous physical printing processes.

In 1796, Alois Senefelder of the Kingdom of Bavaria created lithography. A smooth slab of limestone was utilized in the very early stages of lithography.

Thanks to the application of the oil-based art, a water-based gum arabic combination was applied, with the gum sticking only to the non-oily surfaces. Water attached to the gum arabic areas during printing and was rejected by the oily sections, whereas the printing ink did the reverse.

Lithography on Limestone

Lithography printmaking occurs because water and oil repel each other. The image is drawn on the print plate’s area with an oil-based medium, which may be tinted to make the artwork visible. There are several oil-based media to choose from, but the picture of the stone’s longevity is determined by the concentration of the substance and its capacity to survive water and acid. An aqueous mixture of gum arabic, mildly acidified with nitric acid, is spread to the stone after the picture is drawn.

The goal of this mixture is to coat all non-image surfaces with a hydrophilic coating of gum arabic and calcium nitrate salt.

The gum solution seeps into the stone’s pores, forming a hydrophilic coating around the original picture that prevents the printing ink from adhering to it. The printer then uses lithographic turpentine to remove any excess oil drawing materials, but a hydrophobic molecular covering of it stays firmly attached to the stone’s surfaces, resisting gum arabic and water but prepared to receive the oily ink.

The stone is maintained moist with water during printing. The water is naturally drawn to the coating of gum and salt that the acid wash has generated. The surface is subsequently rolled with printing ink based on drying oils like linseed oil and varnish filled with pigment. The oily ink repels water, but it accepts it in the hydrophobic patches left by the original drawing medium. The paper and stone are passed through a press that produces uniform pressure over the surfaces, moving the ink off the stone and onto the surface of the paper when the hydrophobic picture is loaded with ink.

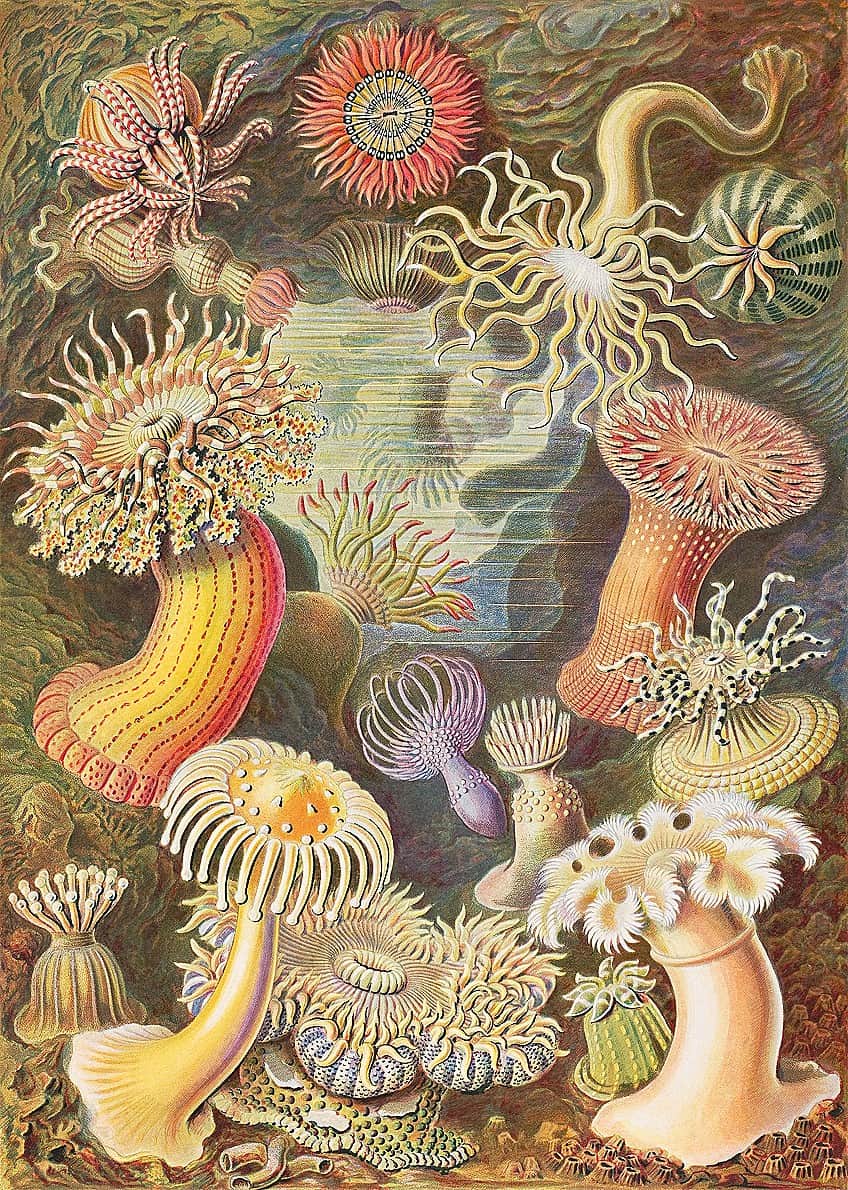

Senefelder had dabbled with multicolor lithography in the early 19th century, and in his 1819 book, he prophesied that the technology will be developed and used to copy paintings.

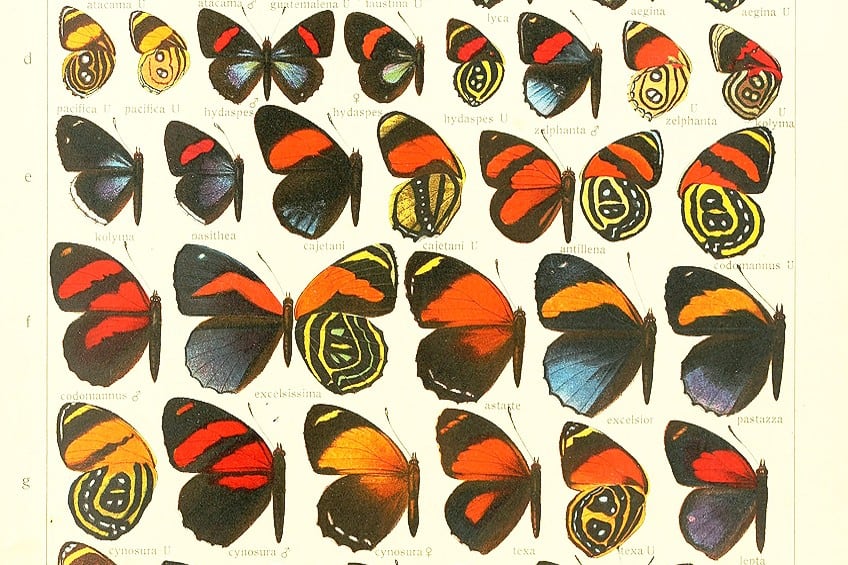

Godefroy Engelmann invented chromolithography technology in 1837, which allowed for multi-color printing. Each color was printed on a different stone, and each print went through the press independently. The primary difficulty was keeping the photos aligned. This style suited itself to graphics with big swaths of flat color, which resulted in the period’s signature poster designs.

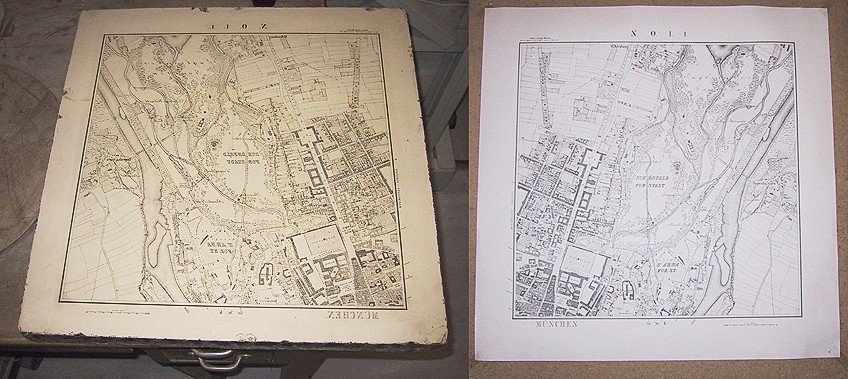

After approximately 1852, lithography generally replaced engraving in the manufacturing of English commercial maps. It was a simple, low-cost method that had previously been employed to manufacture British army maps during the Peninsular War.

Most commercial maps from the second half of the 19th century were lithographed and unappealing, though they were accurate enough.

Modern Lithography Process

Maps, posters, books, magazines, and packaging—basically any smooth, mass-made object with print and graphics—are all manufactured using high-volume lithography. Offset lithography is currently used to print most books, and indeed all sorts of high-volume text. Rather than stone tablets, flexible polyester, aluminum, or paper printing plates have been used in offset lithography, which relies on photographic techniques.

A photosensitive emulsion is used for modern printing plates, which have a scraped or coarse texture.

The plate is subjected to ultraviolet light after a photographic negative of the intended picture is brought in proximity to the emulsion. The emulsion exhibits a reversal of the negative picture after development, resulting in a copy of the original image. Direct laser imaging in a CTP device called a platesetter can also be used to generate the picture on the plate emulsion. The film that remained after imaging is the positive image. Non-image elements of the emulsion have typically been eliminated by a chemical procedure, however, plates that do not require this processing have recently been available.

On a printing press, the plate is attached to a cylinder. Water is applied by dampening rollers to the blank areas of the plate but is rejected by the emulsion in the picture region. The inking rollers then administer a water-repellent ink that only adheres to the film of the picture region. If you transferred this image straight to paper, you’d get a mirror image and the paper would become excessively moist.

Alternatively, the plates roll against a cylinder wrapped in a rubber covering, which presses out the water, takes up the ink, and applies consistent pressure to the paper.

When the paper goes between the cover cylinders and the impression cylinders, the image is transferred to the sheet. Because the image is initially imprinted on the rubber-wrapped cylinder, this reproduction method is known as offset lithography. Over the years, several breakthroughs and technological improvements in printing technology and presses have been produced, including the invention of multi-unit presses that can print multi-color graphics on both sides of the sheet in one pass, and web presses that support continuous rolls of paper.

Further development was Dahlgren’s creation of the continuous dampening mechanism, which superseded the traditional approach, which uses rollers covered in fabric that collects water that is still used on outdated presses. Enhancing control over the water flow to the plate, this increased water, and ink equilibrium. A dampening device delays the roller in connection with the plate, allowing it to pass over the ink image to erase flaws termed “hickies.”

Because the ink is transported via numerous layers of rollers with diverse purposes, this press is also known as an ink pyramid. Newspapers are frequently printed using fast lithographic ‘web’ printing machines.

The introduction of desktop publishing allowed text and graphics to be quickly edited on home computers before being printed on desktop or commercial presses. With the emergence of digital image-setters, print businesses could make negatives for plate making straight from digital input, bypassing the intermediary process of shooting a page layout. The advent of the digital plate setter in the late 20th century completely removed the need for film negatives by directly exposing printing plates to digital input, a method known as computer-to-plate printing.

Lithography Artists

Lithography had a limited impact on printmaking in the early19th century, owing to technical challenges that had yet to be addressed. During this time, Germany was the primary producer. Godefroy Engelmann, who transferred his press from Mulhouse to Paris in 1816, essentially solved the technical issues, and lithography was accepted by painters like Géricault and Delacroix during the 1820s.

London became a central hub after experimentations like Specimens of Polyautography (1803), which featured experimental creations by a multitude of British creatives.

These included Henry Fuseli, Benjamin West, James Barry, Thomas Stothard, Richard Cooper, Henry Richard Greville, Henry Singleton, and William Henry Pyne. Goya’s final lithographic series, The Bulls of Bordeaux (1828), was created in Bordeaux.

Further Developments

By the mid-century, both countries’ initial enthusiasm had faded, however, lithography was becoming increasingly popular for commercial uses, including the works of Daumier that were published in newspapers. In France, Jean-François Millet and Rodolphe Bresdin practiced the medium, as did Adolph Menzel in Germany. In 1862, the publisher Cadart attempted but failed to launch a portfolio of lithographs by several lithographers, which included many Manet works.

During the 1870s, the renaissance began, notably in France, with painters like Odilon Redon, Henri Fantin-Latour, and Edgar Degas producing most of their work in this fashion. The need for very restricted editions to keep the price stable had now become apparent, and the medium gained acceptance.

Color lithography gained notoriety in the 1890s as a result of the work of Jules Chéret, known as the “Father of the Modern Poster,” whose works influenced a new era of poster artists and painters, including Georges de Feure and Toulouse-Lautrec. By 1900, the medium had become an acknowledged element of printing in both color and monochrome.

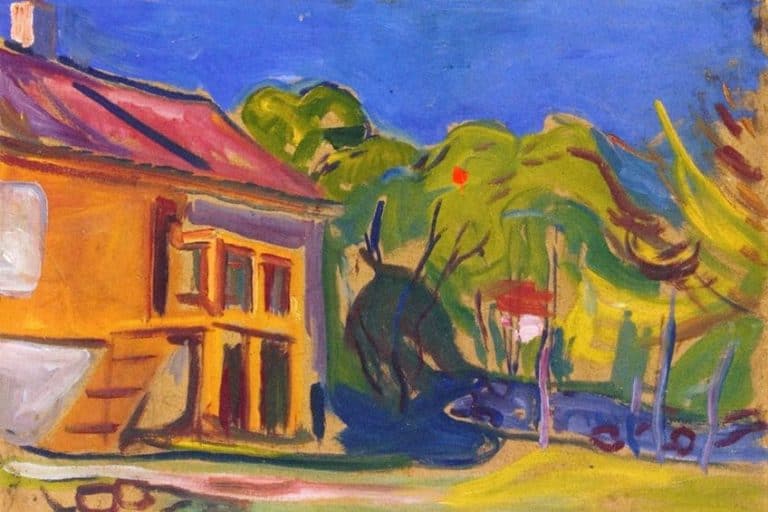

Calder, Chagall, Braque, Dufy, Miró, Matisse, and Picasso were among the artists who rediscovered lithography throughout the twentieth century, due to the Mourlot Studios, a Parisian printshop established in 1852 by the Mourlot family.

More Artists Start Exploring the Medium

Fernand Mourlot, allowed several 20th-century painters to investigate the complexity of fine art printing at the Atelier Mourlot, which specialized in wallpaper printing at the time. Mourlot urged artists to work straight on lithographic stones to create unique artworks that could later be printed in small editions under the supervision of expert printers.

Lithographs were created as a consequence of the collaboration of a modern artist and a professional printer to market the artists’ work as posters.

George Bellows, Grant Wood, Max Kahn, Eleanor Coen, Pablo Picasso, Jasper Johns, Susan Dorothea White, David Hockney, and Robert Rauschenberg are among the artists who have used the medium to create the majority of their prints.

C. Escher was a specialist in lithography, and several of his prints were made with this technique. Lithographers, more than other printing techniques, rely heavily on competent printers, and the evolution of the medium has been heavily impacted by when and where these have been founded.

The serilith process is a type of lithography that is sometimes utilized. Seriliths are mixed-media unique prints made by combining the lithograph techniques.

This sort of fine art print is widely appreciated and collected by many artists and publishers throughout the world. The artist hand-draws the separations for both techniques. The serilith method is generally used to make limited edition fine art prints.

The Difference Between a Lithograph and a Print

If you’re not sure if you’re looking at a true lithograph or another style of print, using a magnifying glass and an educated eye can help you figure it out. To tell whether you’re looking at a hand-pulled or offset lithograph, use the following guidelines.

It’s most likely a genuine stone if you bought it from a respected art dealer or auction house. However, utilize the suggestions above to double-check the seller’s cataloging.

- You should look for a signature. A signature is usually included on the reverse of hand-pulled lithographs, but not on offset lithography prints and copies.

- Using a magnifying glass, search for columns of dots. In rows, offset lithography leaves a dotted circular pattern. If the lithograph was made by hand, the print will almost certainly have random ink dotting or discoloration.

- Examine any discoloration. Look for evidence of chemical oxidation or defects in non-image areas, which can occur when offset lithography’s metal printing plates aren’t properly maintained.

- Feel the ink thickness with your fingers. The ink on the surface of the print will be somewhat elevated in original stone lithography, as opposed to the flatness of the ink visible on offset lithographs. Wearing gloves and proceeding with caution might assist avoid smudging the ink.

Given the enormous range of prints available on the market, distinguishing lithographs from other printing methods can be particularly challenging. The technique is characterized as a printing technique that makes use of the immiscibility of water and oil when they come into contact. While other printing technologies need etching and other impressions, lithography is distinctive in that it mimics painting more closely.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Lithography Art?

Lithography began in the 18th century, when Alois Senefelder, a little-known Bavarian playwright in Germany, discovered that he could copy his scripts by drawing them on slabs of limestone with grease crayons and printing them with rolled-on ink. Due to this material’s capacity to continually retain crayon markings put on its surface, he rapidly recognized lithographs could be produced in practically infinite amounts.

How Does the Lithography Process Work?

Original pieces of art are printed and replicated using flat stones or metal plates to make lithographs. The lithograph is created by the artist sketching a design straight onto the printing element with litho crayons or specialist grease pencils. The area is then coated with a chemical etch after the artist is pleased with the drawing on the stone. The procedure permanently adheres the oily sketching materials to the surface. The blank portions of the plate will attract moisture and resist lithographic ink, whereas the sections that have been drawn on will hold the ink. The unpainted sections are then cleaned with water to help stop the ink from spreading.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Lithography – Understanding the Art of Lithography Printmaking.” Art in Context. June 16, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/lithography/

Meyer, I. (2022, 16 June). Lithography – Understanding the Art of Lithography Printmaking. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/lithography/

Meyer, Isabella. “Lithography – Understanding the Art of Lithography Printmaking.” Art in Context, June 16, 2022. https://artincontext.org/lithography/.