Classical Art – Understanding this Highly Influential Style

Classic art styles from the ancient Greco-Roman periods have influenced the works of artists for centuries. What is it about the art from these periods that continues to inspire artists from Leonardo da Vinci to Banksy? Classical notions of proportion, balance, harmony, and elegance subtly permeate the sculptures, architecture, and paintings of many modern art movements. In this article, we are going to take a deep dive into the fundamentals of Classical art and explore its continued influence.

Table of Contents

- 1 A Broad Overview of the Classical Aesthetic

- 2 Key Stylistic Contributions From Ancient Greece

- 3 Key Stylistic Contributions From the Roman Empire

- 4 Long Live Classicism

A Broad Overview of the Classical Aesthetic

The Classicism definition of art and architecture from the Greco-Roman eras emphasizes the qualities of balance, harmony, idealization, and sense of proportion. The human form was a common subject of Classical art and was always presented as a generalized and idealistic figure with no emotionality. The composition and line in Classical styles are far more important than the use of color.

Classical architecture is underlain by Classical concepts of mathematically precise proportions that create balance and symmetry. The eras of Greek and Roman Classicism saw a monumental level of architectural innovation, from the invention of cement to the use of the dome. Elements of Classical architecture continue to permeate Western theories and practices today.

Before we can investigate the influence of Classicism artists throughout the ages, it is essential to understand how the elements of the Classicism definition developed. The style spans centuries, cultures, and continents. We begin with the earliest utterances of the Classical style in Mycenaean Greece and finish in the Imperial Roman Empire.

Key Stylistic Contributions From Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is the starting point in our journey through Classicism. We can see the spark of Classicism in the vase paintings of the early Mycenaeans and the development of the golden ratio. First, we look at the historical development of Ancient Greek culture, and then we will look closer at some of the most important contributions to Classicism.

1600-1100 BCE: Early Mycenaean Influences

The Mycenaean civilization is considered the first Greeks, and their style of art, sculpture, and architecture were fundamental building blocks for later Greek Classicism. Geographically, this elite warrior civilization spanned the coastal areas of modern-day Italy, Turkey, Syria, and Southern Greece.

Mycenaean society was governed by palace states and can be separated into three classes: slaves, common people, and attendants of the king. The king of each palace state wielded religious, political, and military authority. Heroic warriors and gods were worshiped by the Mycenaean people and early Mycenaean art often pay homage to these figures. The tales of these gods and warriors lived on in later Greek literature, like the Odyssey by Homer.

The drivers of Mycenaean geographical and political expansion were trade and agriculture. The Mycenaean engineering genius enhanced both of these drivers with drainage systems, dams, harbors, bridges, aqueducts, and a road network only rivaled by the Romans. Cyclopean masonry created enormous fortifications from large boulders held together with mortar.

These innovative architects created the relieving triangle, a common practice today whereby a triangular space is left above the lintel to keep stone archways from collapsing.

Mycenaean societies were the first to create the acropolis hill-top fortress that came to characterize later Greek towns. The center of the king’s palace was a circular throne room often decorated with vibrant frescos. These frescos depicted goddesses and gods, battle scenes, the ocean, hunting parties, and symbolic processions. Following the Mycenaean era of prosperity, the Greek Dark Ages saw the Geometric style of vase painting.

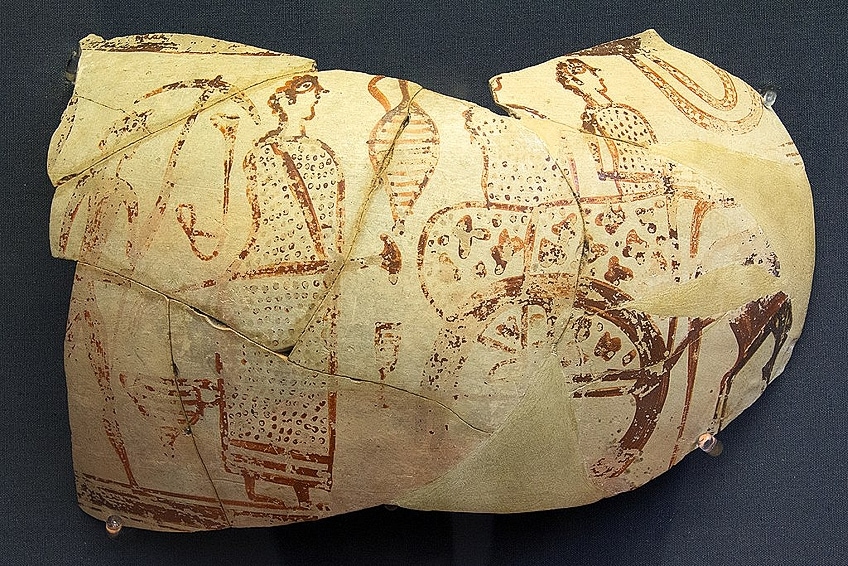

Vase Painting

Although vase painting continued throughout the following periods of Ancient Greek history, it has its roots in the Mycenaean era. The vase painting of Classicism artists exemplifies the Ancient Greek focus on portraying the human form in an increasingly realistic manner.

Geometric patterns adorn the earliest vase paintings, but the focus quickly shifted to the human figure. Following this, vase painting became more oriental, depicting Eastern motifs. The black-figure style followed, using black to present more accurate and detailed human figures.

Another style of vase painting arose during the Classical Greek era using red rather than black figures. Vase painters in this style crafted human figures with strong outlines on black backgrounds. This technique allowed artists to paint the fine details rather than incising them into the clay. The resulting color and line variations are more rounded than the patterns from the Geometric era.

776-480 BCE: Greek Archaic Period

The establishment of the first Olympic Games marked the beginning of the Greek Archaic period. For this Greek civilization, human achievement as personified by the athletic games set them apart from “barbarian” people not of Greek descent. The Mycenaean era was valorized by the Archaic Greeks, leading to the idealization of the male form.

For the Greeks of this period, the nude male figure represented the epitome of bodily beauty and character nobility. It stands to reason that the male form featured heavily in the Classical art of this Greek period.

The Greek Archaic period also saw significant shifts in social and political life. The political and social system of the Archaic Greeks was based on the city-state. Sparta was a city with immense military power, while Athens became the center of western art, philosophy, science, and culture. Around 594 BCE, a philosopher king, Solon, created a political body that could challenge the king and fundamentally shift the political landscape of the day.

People were no longer placed into slavery for debt, and the ruling class was established based on wealth, not descent. Extensive sea-based trade drove the Greek economy, and many city-states began establishing settlements across the Mediterranean. As a result, Greek cultural, artistic, and political ideals spread to other European cultures like the southern Italian Etruscans.

The most significant artistic innovation of this period in Greek history was figurative sculpture. These idealized yet realistic sculptures took influence from Egyptian sculpture and the idealization of the nude male form. The Cyclades islands were the birthplace of the first life-sized sculptures of young women (kore) and men (kouros). Towards the end of the Archaic era, sculptors like Nesiotes, Kritios, and Antenor rose to fame.

In 510 BCE, Antenor created the bronze Tyrannicides in commemoration of Aristogeion and Harmonides, the two assassins of Hipparchos. These two men symbolized the transition towards democracy. The significance of this sculpture lies in the fact that it was the first recorded piece of publically funded art. The sculptor, Kritos, recreated the sculpture in the Early Classical style with individual characterization and realistic movement, following its disappearance when the Persians invaded.

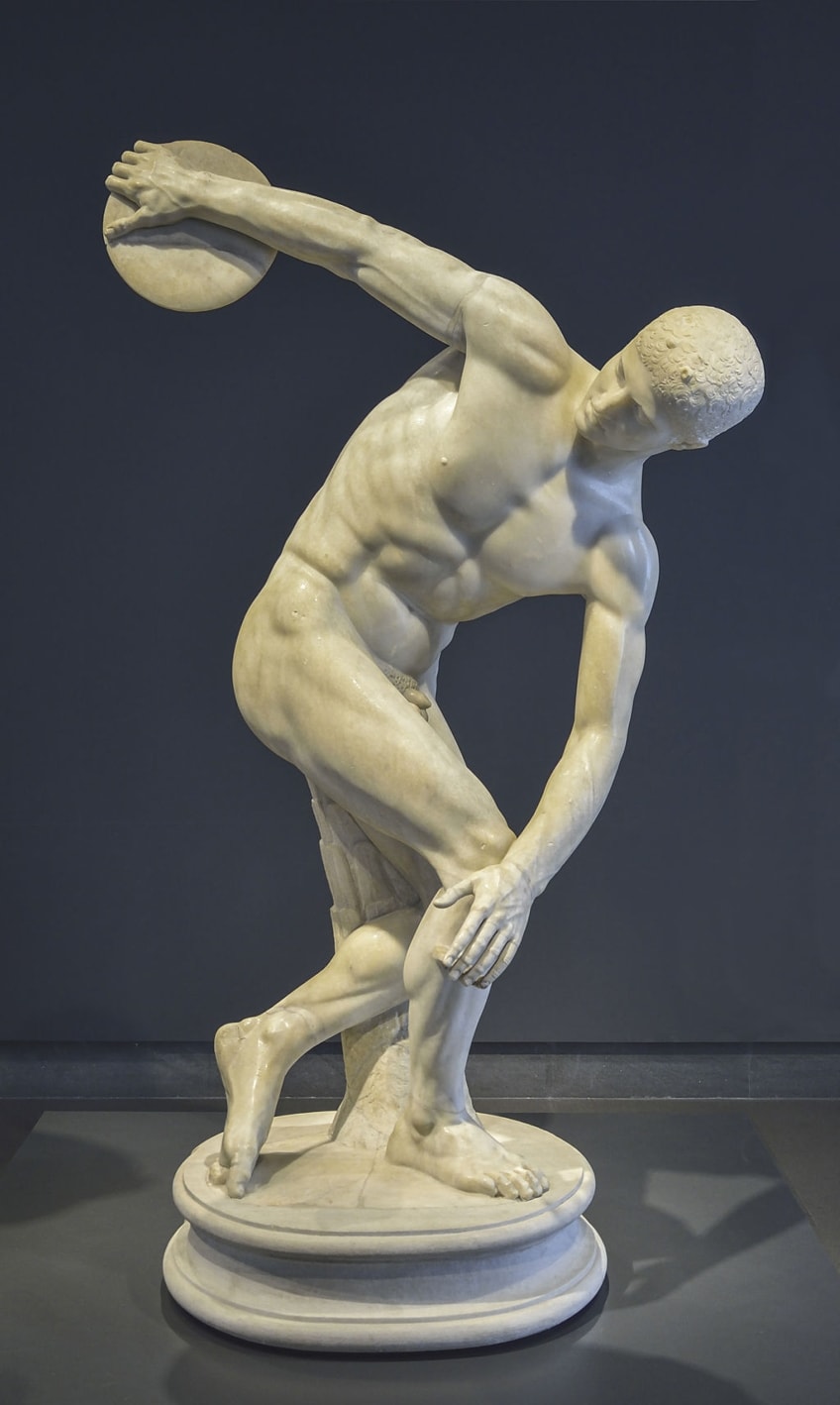

Greek Classicism Sculpture: Molding the Classical Style of Sculpture

Ancient Egyptian sculpture was very influential to Greek sculptors from the Archaic period. Greek sculptors created life-sized sculptures of kouroi. There are three distinct types of kouroi: the standing and dressed young woman, the nude young man, and the seated woman.

Funerary monuments, votive statues, and public memorials featured the characteristic “Archaic smile”. The sculpted representations of the human figure were more idealistic than realistic and were rarely of individuals. Archaic Greek sculpture captures human movement through realistic anatomy.

The late Archaic era saw the celebrity of sculptors like Kritios, Phidias, Myron, Lysippus, and Scopus, to name a few. Discobolus, a sculpture by Myron, became famed for being the first sculpture to capture the balance and harmony of human movement in a moment. Classic Greek sculpture, as with painting and architecture, became increasingly focused on mathematically precise beauty. Polycleitus’s systems of mathematical proportions focus on creating rhythm and balance through symmetry.

Early Greek bronze sculptures were created using hammered sheets held together with rivets. Techniques became more advanced by the end of the Archaic period. Greek sculptors started to use the lost wax method of bronze sculpture. Large-scale sculptures were created by casting the bronze in several pieces. These pieces would then be welded together, and the teeth, eyes, fingernails, lips, and nipples were formed from copper inlays.

Unfortunately, a large number of the original Greek bronze statues do not exist today. The early Christian era melted down several statues believed to represent pagan idols. Of those that remain, the Raice bronzes, the Charioteer of Delphi, and the Artemision Bronze are notable examples.

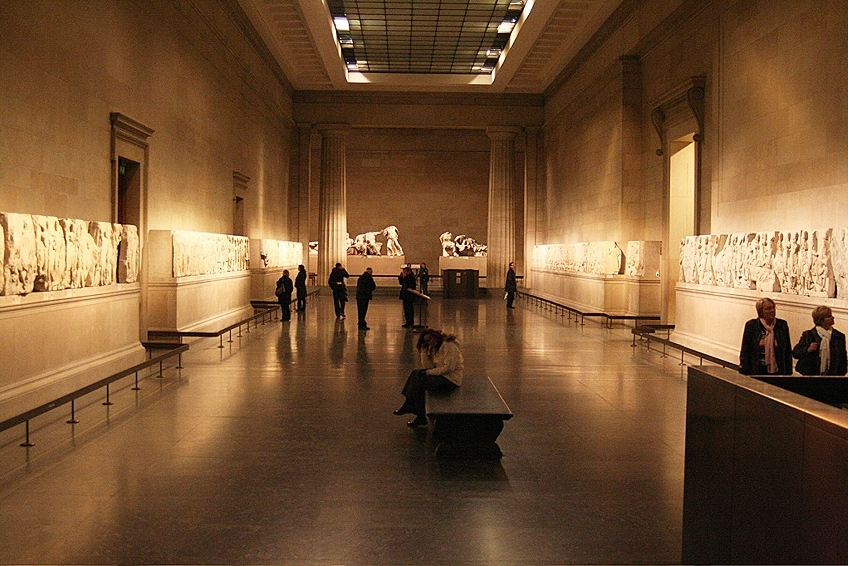

As well as three-dimensional sculptures, Greek sculptors decorated temple entablatures with relief sculptures depicting mythological scenes and legendary battles. The Parthenon Marbles, created by Phidias, are perhaps the most famous examples of this style of Classical Greek sculpture. These relief sculptures are known for their dynamic movement and realism and decorated the temple chamber’s interior walls. This sculpture, and other reliefs of this time, have influenced later artists like Auguste Rodin.

Chryselephantine statues in gold and ivory were a popular form of Classicism sculpture during the early Archaic period. Phidias worked in these mediums, creating the 43-foot-tall Statue of Zeus at Olympia (435 BCE) and the almost 40-foot-tall Athena Parthenos (447 BCE). A wooden structure is a basis for both of these statues, and ivory limbs and gold panels are attached in a segmental fashion. These impressive statues stood not only as an expression of Ancient Greek power and wealth, but also as symbols of the gods.

Unfortunately, neither of these sculptures are standing today. What we know of them comes from descriptions and representations on coins.

480-323 BCE: Classical Greece

Also known as the Golden Age, the philosophy, art, science, politics, and architecture of the Classical Greek period were fundamentally influential for the developing Western civilization and the Roman Empire. Western philosophy has its roots in the writings of Aristotle, Plato, and Socrates. Although key aspects of their philosophy diverged, Aristotle and Plato agreed that art should aspire to recreate the beauty of the natural world.

Freedom of speech and the assembly of a Greek government of citizens defined a new age of Greek democracy. Sculptor Phidias and Pericles rebuilt the Parthenon in Athens. The power and cultural influence of Athens increased and spread throughout the Mediterranean.

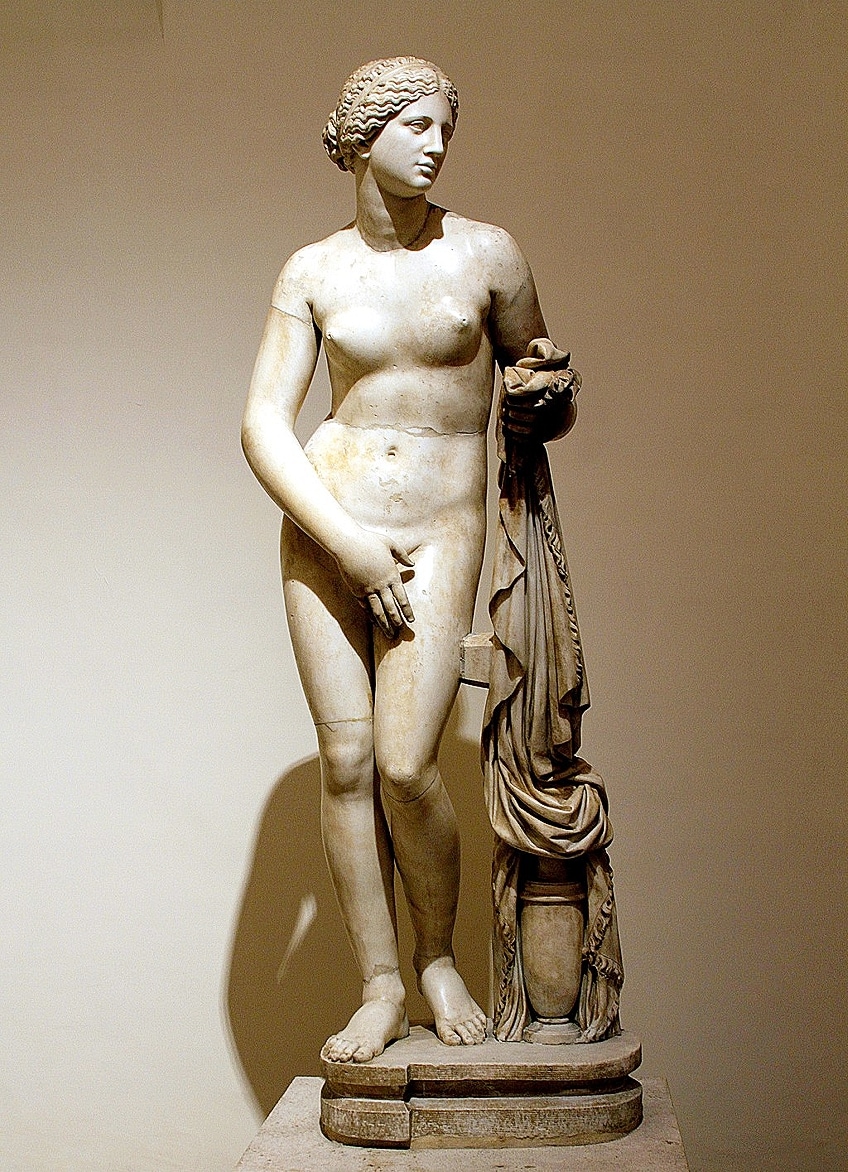

With the growing emphasis on the individual in Classic Greek society came an increase in personalized art. Sculpture for funerals became increasingly realistic in emotional expression, as opposed to the idealization of the past. The nude male form continued to be celebrated in bronze sculpture. The female form also began to get attention, as seen in Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos.

The Golden Ratio: The Beauty Proportion

For Ancient Greek philosophers and artists alike, there was a close association between beauty and truth. As the Ancient Greeks did, we can understand beauty and truth in mathematical terms. Aristotle’s golden mean represented the way to live a life of virtuous heroism by avoiding any extremes. For Socrates, all areas of virtue and beauty were manifestations of proportion and measurement.

Pythagoras and Euclid developed the golden ratio based on two quantities and the proportion between them. The ratio between these two measurements should be equal to the ratio between the larger measurement and the sum of the two measurements.

A substantial amount of Ancient Greek architecture employed the golden ratio, with perhaps the most well-known being the Parthenon. Phidias oversaw the building of the Parthenon. Today, the golden ratio is known by the Greek letter phi to honor Phidias’ contribution to the most perfect building imaginable.

For many Classic artists and architects, the golden ratio has remained an integral concept. Vitruvius, the Roman architect, used the golden ratio, and his principles had a profound effect on the art and architecture of the Renaissance period. Even modern architects like Le Corbusier find inspiration in the golden ratio.

323-31 BCE: The Age of Hellenistic Greece

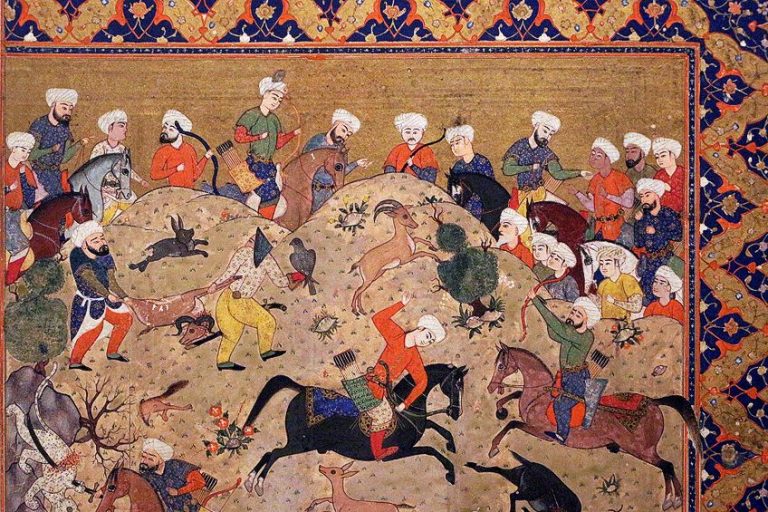

The Hellenistic era in Greece started with the death of Alexander the Great. Following his death, a political scramble left the Greek empire divided into three separate states. The influence of mainland Greek culture was in a gradual decline, while Hellenistic culture flourished in Egyptian Alexandria and Syrian Antioch. The immense wealth that remained in these epochs of the Greek empire led to the arts having royal patronage. Architecture, sculpture, and painting, in particular, flourished with backing from the royal courts.

Lysippus was the official sculptor for Alexander the Great, and following Alexander’s death, crafted bronze sculptures that mark the transition from Classical to Hellenistic styles. Some of the most well-known artworks from Ancient Greece were created during the Hellenistic period.

Much of the art from the Hellenistic era had functional purposes. Early Hellenistic sculptures were often, first and foremost, votive gifts and architecture focused on civil monuments with social value. Artistic value for Hellenistic artists came second to function.

It was during the Hellenistic era that great strides in Greek architectural design took place. With a focus on urban planning, Hellenistic architects designed theaters, parks, and buildings for other recreational activities. The Corinthian order is perhaps the most decorative Classic order and is exemplified in the colossal temples of the time.

The city of Pergamon, known for its enormous architectural complexes, became a cultural epicenter of the Hellenistic period. A stunning example of Hellenistic architecture is the Pergamon Altar. It was during the Hellenistic era that Greece became slowly integrated into the Roman Empire.

Ancient Greek Architecture: Laying the Foundations

Ancient Greek architecture is perhaps best known for its temples that embody the cultural emphasis on formal unity. The temples were often rectangular and framed by open colonnades. Ancient Greek architects developed three orders of Classic architecture: the Corinthian, the Ionic, and the Doric. These orders set the foundations for Roman architecture, and the concepts spread throughout Europe and America.

Each order stemmed from distinct places and times in Ancient Greece. It is possible to distinguish between the architectural orders based on the capitals, the columns, and the entablature. The Doric order uses circular capitals, fluted or smooth columns, and entablature features that add a more elaborate and embellishing element to the simple design.

The use of scrolls or volutes to accent the top of the capital is typical of the Ionic order. Narrative frescos extend across the length of Ionic buildings as a result of the entablature design. The Corinthian order is a later Classical architectural design named after the city of Corinth. Corinthian architecture is by far the most elaborate, with acanthus leaf motifs and decoratively carved capitals.

The first Ancient Greek temples were constructed from wood using a post and beam design. Stone and marble became increasingly popular, and the Parthenon was the first temple to be constructed entirely from marble. Ancient Greek architects were pioneers of the amphitheater and the stadium. The Romans later appropriated these architectural structures.

Frescos: A Bridge Between Ancient Greek and Roman Classicism Period art

Although architecture and sculpture are the most common forms of Classical art, Greek and Roman painters made classical innovations in panel and fresco painting. Most of what we know about Classical Greek painting comes from the painted vases and Roman and Etruscan murals influenced by the Greeks. One stunning example of Classic Greek frescos is the mural Hades Abducting Persephone in the Vergina tombs. This mural reflects the increased realism of Greek paintings and sculptures of this time.

A great deal more Roman fresco and panel paintings survive. The excavation of Pompeii in 1748 revealed several very well-preserved Roman frescos in residences like the House of the Vettii, the House of the Tragic Poet, and the Villa of Mysteries. These fresco paintings brought a sense of color, light, and space into interiors that were often dark, cramped, and lacked windows.

Popular fresco subjects included scenes from the Trojan war, religious rituals, landscapes, mythological tales, still lifes, and erotic scenes. Often walls would be painted to resemble alabaster panels or brightly colored marble, often enhanced by illusionary cornices or beams.

Key Stylistic Contributions From the Roman Empire

In the Roman Classicism period, art took a great deal of inspiration from the artistic and cultural developments of Ancient Greece. Building on the Greek valorization of heroic figures and grand architecture, the Romans build cities, commissioned public art, and developed Classical portraiture.

509 BCE-26 CE: The Roman Republic

The Roman Senate, a collection of noblemen, elected the kings in the Roman Republic, which began as an immense city-state. Rome became a Republic following the expulsion of the last King, Lucius Tarquinii Superbus, in 509 BCE. Tarquinii was deposed by the husband and father of a noblewoman raped by his son. Not only was this story central to the History of the Roman Republic, but it was also a central subject of Roman art in the centuries that followed.

Following the abolition of kingship, the Roman Republic established a new governing system led by two consuls. The governing upper class and the common people were often in conflict, and this situation inspired much of the architecture in early Rome. City planning on a grid system emphasized public entertainment facilities to keep the peace. In the 3rd century, the Romans developed concrete revolutionizing engineering and architecture.

Many of the Greek stories of heroes and gods were adopted by Roman culture, alongside their way of the ancestors’ traditions. This tradition was an almost contractual relationship between Rome’s founding fathers and the gods. Greek sculptures taken during the war were often displayed in Roman homes, public places, and palaces on the basis of their aesthetic value.

The Greek Classical traditions discussed above were the primary influence on Roman architecture and art.

The Concrete Revolution: Classical Advances in Roman Architecture and Engineering

The Romans took architectural advancement to new levels. Technological innovations, including the invention of concrete, meant that architectural design was no longer limited to bricks and mortar. The dome, barrel vault, arch, and groin vault were Roman architectural innovations.

The Roman era saw an age of incredible architecture, not only for pleasure like the Colosseum, but also to improve city life like aqueducts, bridges, and apartment buildings. The arch is one of the most influential architectural developments from Roman Classicism. The segmental arch was pioneered for use in bridges and homes, while the triumphal and extended arches celebrated the emperor’s victories.

The use of the dome is by far the most significant innovation of Classical Roman architecture. Roman architects were influenced by Greek architectural styles and the Etruscan use of hydraulic technologies and arches. Even when porticos, columns, and entablatures were no longer needed for structural integrity thanks to technological advancements, the Romans still used them.

Vitruvius is the most famous Roman architect and engineer. Between 30 and 15 BCE, while working for the military of Augustus, Vitruvius wrote the Ten Books on Architecture. These books are a record of Roman architectural theory and practice, describing the process of town planning, religious building, different building materials, aqueducts and water supplies, and various types of Roman machinery like cranes and hoists.

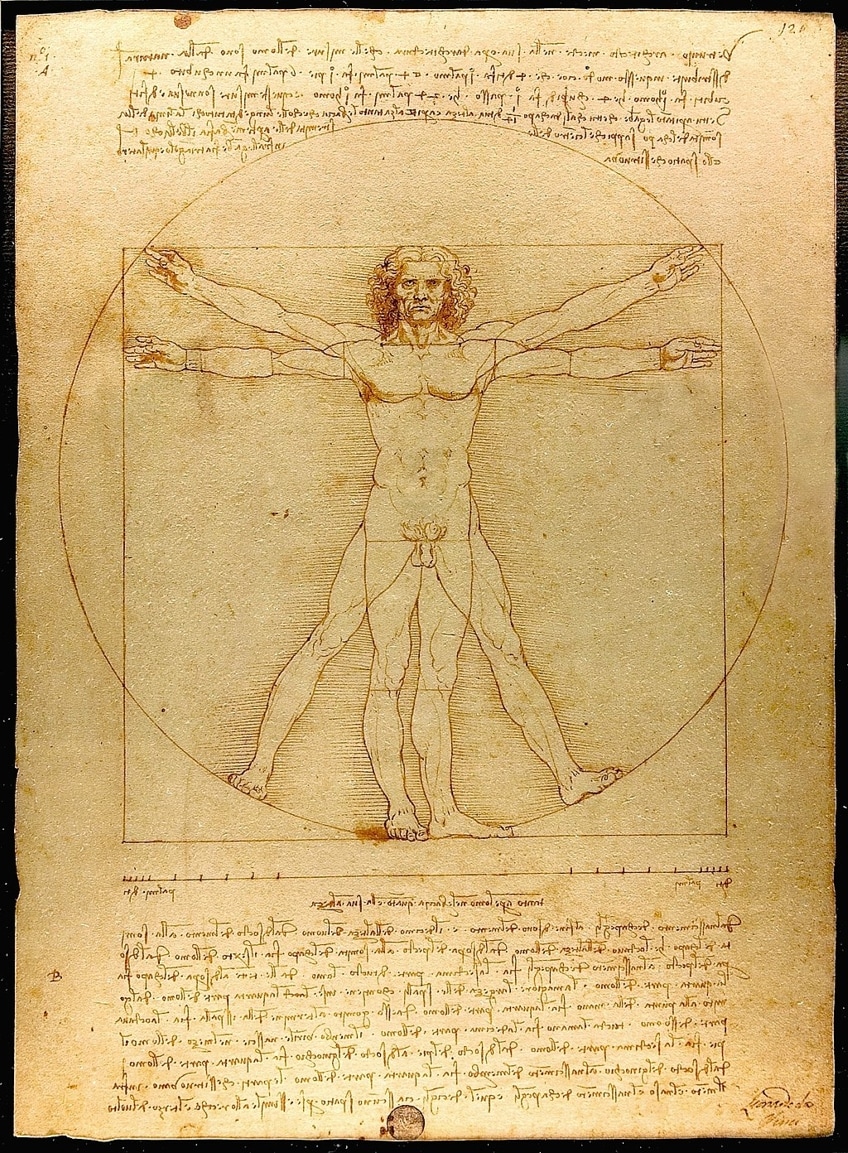

The Vitruvian Triad refers to Vitruvian’s theory that any built structure should have the qualities of beauty, stability, and unity. The Vitruvian architecture reflects the proportionate beauty of the natural world and the human form. The extension of Vitruvian proportion to the human figure is reflected in Vitruvian Man (1490) by Leonardo da Vinci.

27BCE-393 CE: The Imperial Roman Empire

Despite the civil war that followed Caeser’s attempt to become emperor, Augustus eventually became the first emperor of Imperial Rome. Augustus reigned for almost 45 years, and during this time, he created the first police force, postal system, fire fighting force, and municipal offices. The taxation and revenue systems implemented by Augustus allowed him to transform the arts and launch a new program of building temples and public buildings.

Artistic works like Augustus of Prima Porta were commissioned and played into the Classical Greek style of idealized representation. The lavish art of Imperial Rome defined this period. Grand architectural buildings were decorated with extravagant frescos and commissioned portraits of the wealthy.

Roman Portraiture: Contributions to Classicism

While many Classic Roman sculptures are little more than copies of Classic Greek sculptures, portraiture is where Roman innovation came into its own. These early Classic portraits emphasized realism. Early Romans felt that representing a powerful man in the most honest way possible was a sign of character.

The tables turned once emperors were reinstated during Imperial Rome. Portraiture in Imperial Rome was idealistic, producing strong politically motivated images presenting the emperors as descendants of heroic Greek and Roman history. This practice led to the development of a Greco-Roman style of relief sculpture.

Roman portraiture also found inspiration in a Greek method of glass painting. Small portraits on medallion-sized pieces of glass or roundels from drinking glasses were popular. Personalized drinking cups containing gold glass portraits were popular among the most wealthy Romans and following their death, these glass portraits would be cut into a medallion shape and placed into the cement walls of the tomb.

Among the most famous Roman portraits are those found on mummified bodies in Fayum. This set of portrait panels was preserved by the dry Egyptian climate and is the largest surviving collection of Classic Roman era portraiture. These portraits display an intermingling of Ancient Egyptian and Classical Roman traditions while Egypt was under Roman rule. The style of these portraits is quite idealistic but the features of each individual are naturalistic and distinct.

Long Live Classicism

The Legacy of Classicism did not fall with the Roman Empire. The influence of Classical Greek and Roman architecture and art permeates all art periods and movements in the Western world. Greek art and Roman architecture were influential for the Byzantine and Romanesque periods.

It was the Italian Renaissance that really took inspiration from the Classical style of Greek and Roman art and architecture. The architectural practice and theory of architects like Palladio and Leon Battista Alberti are informed by Vitruvius’ writings, the Pantheon, and the Parthenon.

The Italian Renaissance: Classicism Art Revival

The Italian Renaissance period in the 15th and 16th centuries is perhaps one of the more durable revivals of Greco-Roman Classicist art. Transitioning from the dark ages of art and culture, European artists, philosophers, and humanists renewed their interest in Classical antiquity. Like Greco-Roman Classicism, the Italian Renaissance period is hailed for its achievements in literature, architecture, painting, philosophy, technology, sculpture, and science.

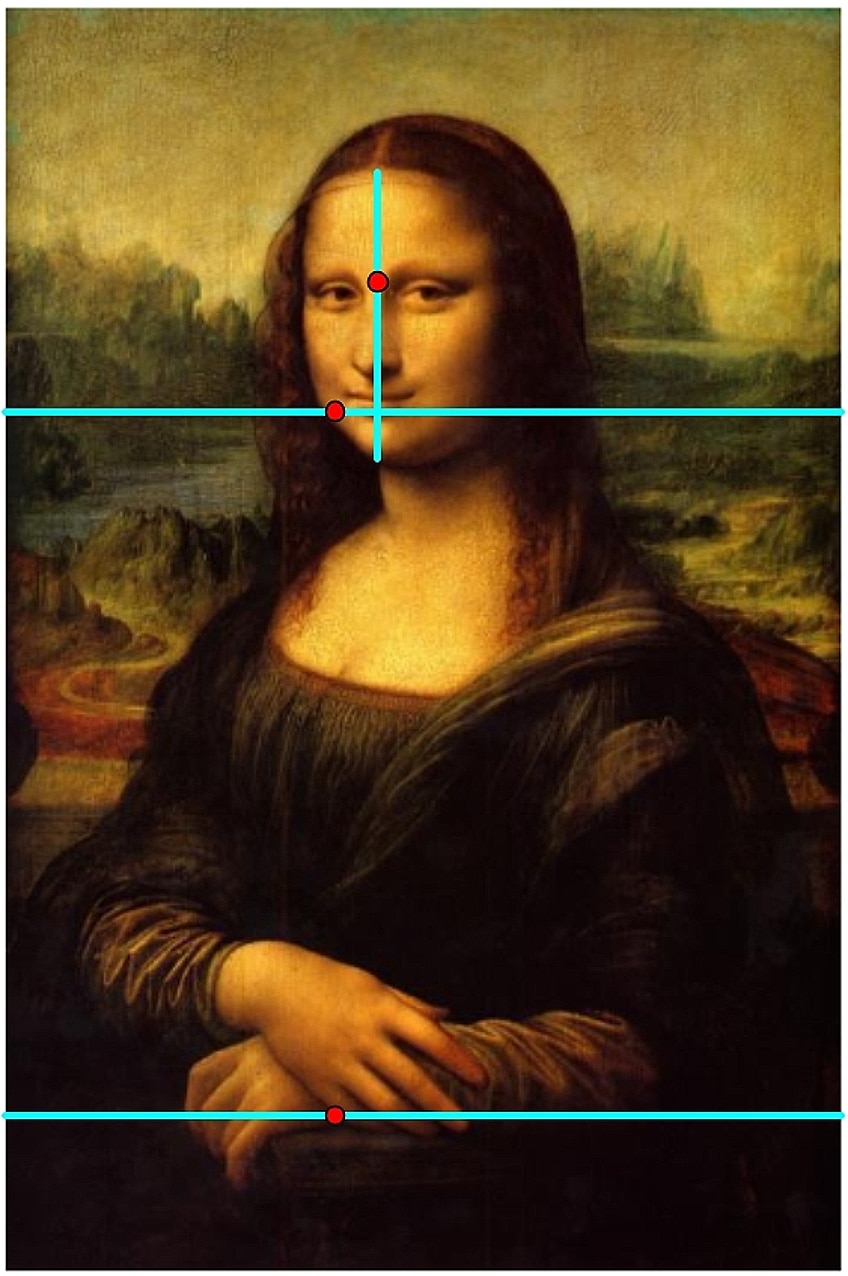

As we have explored in Greek and Roman art and architecture, proportion, beauty, and orderliness were key elements of Italian Renaissance Classicism art. The golden rectangle proportion associated with Roman and Greek architecture found a revival in Renaissance architectural models. Renaissance artists like Albrecht Durer, Raphael, Michelangelo, and Leonardo da Vinci were influenced by Greek sculpture, as were later artists from the Baroque period like Bernini. Below, you can see the golden ratio’s proportions displayed in da Vinci’s famous Mona Lisa painting.

Neoclassicism: Reinventing Classical Ideas

The terms Classicism and Neoclassicism are often confused because of their similarity. While Classicism denotes the particular artistic, architectural, and philosophical aesthetic of the Ancient Greeks and Romans, Neoclassicism reflects any later imitation of these Classical styles.

Neoclassicism broadly refers to the style of Classical imitation, but it also refers more specifically to an artistic movement in Western Europe during the 18th century. This art movement began in Rome, following the discovery of Pompeii. Soon, Neoclassical aesthetics based on Roman and Greek ideas spread throughout Europe.

The Neoclassical art movement occurred in parallel to the Age of Enlightenment during the 18th century and continued into the 19th century. In terms of architecture, Neoclassical aesthetics have continued to be influential in the 21st century. The Neoclassical architectural style emphasizes symmetry and simplicity, tokens from Rome and Ancient Greece, and taken directly from Renaissance styles.

The Neo in Neoclassicism points to the difference between this style and its Greco-Roman inspiration. Neoclassical artists, writers, and sculptors chose some models and styles from Classicist art and ignored others. For example, Neoclassical artists paid homage to the sculptural ideas from Phidias’ generation, but the sculptures that were actually produced are more similar to the Roman remakes of Hellenistic sculptures. Drawings and engravings that reconstructed Greek buildings mediated the Neoclassical impressions of Greek architecture. Neoclassical artists entirely ignored artistic and architectural styles from Archaic Greece.

Although the roots of Classicism feel as though they are in the distant past, the aesthetic ideas continue to permeate many aspects of modern Western life. From architectural designs using cement and arches to the fundamentals of drawing the human figure and influential works of literature, Greco-Roman Classicism is all around us. The Renaissance and Neoclassical celebration of Classical aesthetics is a testament to the innovation of early Greek and Roman artists and architects.

Take a look at our Classical Art period webstory here!

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Classical Art – Understanding this Highly Influential Style.” Art in Context. February 12, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/classical-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 12 February). Classical Art – Understanding this Highly Influential Style. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/classical-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Classical Art – Understanding this Highly Influential Style.” Art in Context, February 12, 2021. https://artincontext.org/classical-art/.