Famous Medieval Paintings – Exploring the Best Middle Ages Paintings

The Medieval period, commonly referred to as the Middle Ages, spans over 1000 years. The Roman Empire’s fall around 300 CE marked the starting point of the Medieval period, which lasted until the beginning of the Renaissance around the early 1400s. This period was an exceptionally influential era of Western art culture which gave rise to many famous Medieval paintings. Major art movements took place during this time. New art genres were created, and different artistic traditions were meshed, including styles from the Middle East and Northern Africa.

Table of Contents

- 1 What Did the Medieval Art Movement Stand For?

- 2 Our Top 10 Most Famous Medieval Paintings to Exist

- 2.1 Christ Pantocrator (Sinai) (c. 500 – 600)

- 2.2 Lamentation (The Mourning of Christ) (1306) by Giotto di Bondone

- 2.3 Maestà (c. 1308 – 1311) by Duccio di Buoninsegna

- 2.4 Ognissanti Madonna (c. 1310) by Giotto di Bondone

- 2.5 Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus (1333) by Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi

- 2.6 The Allegory of Good and Bad Government (c. 1338 – 1339) by Ambrogio Lorenzetti

- 2.7 Crucifixion Altarpiece (c. 1394 – 1399) by Melchior Broederlam

- 2.8 Wilton Diptych (c. 1395 – 1399)

- 2.9 The Trinity (c. 1411 – 1427) by Andrei Rublev

- 2.10 Adoration of the Magi (1423) by Gentile da Fabriano

- 3 Frequently Asked Questions

What Did the Medieval Art Movement Stand For?

Medieval art was established from the Roman Empire’s artistic heritage and the Early Christian church’s iconographic customs, along with the “barbarian” style of Northern Europe. The mix of these sources led to the development of an incredible artistic legacy. The Medieval art period encompassed different artistic movements, involving mainly the Early Christian art movement, the Byzantine art movement, the Romanesque art movement, and the Gothic art movement.

Although the style of the art produced during this period varied, it was unified by various common factors. Most importantly, it reflected the sweeping popularity of Christianity.

Middle Ages paintings were rich with religious symbolism and imagery. Medieval artists and their paintings predominantly portrayed holy figures and biblical narratives. These narratives had a hierarchy, which was predominantly dictated by the spaces the paintings would occupy. The Medieval artwork that depicted scenes considered to be more important would occupy notable focal points in a church or altarpiece, whereas less significant scenes would radiate outwards.

These Medieval art examples could be roughly classified into fresco, panel, illuminated manuscript, and iconography painting.

Although Medieval artwork primarily served a religious function, there was an increase in secular subject matter that was being included in Middle Ages paintings. The visual arts went through a transitional period during the Medieval era, as the objectives of artists endured a radical change.

Medieval painters shifted from the rigid formulas necessitated by Romanesque painting, towards a representation of the world that was more realistic and a desire to achieve a three-dimensional effect in their painting. This introduction of Medieval paintings that portrayed non-religious subject matter and secular details allowed artists to express a variety of emotions and depict contemporary life more realistically.

Additionally, decorative art was common in Medieval paintings.

Religious paintings often had gold in their backgrounds, on which heated tools were sometimes used to imprint intricate designs through a process called ‘tooling’. Medieval painters accomplished elegant design in their artwork by curving the draperies and depicting the sway and movement of the human body. Bodies were no longer depicted as stiff and flat; the illusion of movement and fluidity was becoming common practice.

The Medieval art period remains a prevalent area of study for collectors and scholars, as a large volume of Medieval artwork produced during this period has been recognized for its historical significance. Medieval artists and their paintings demonstrated the technical advancements and extensive achievements of this period, which were fundamental to informing the progress of later Western art.

Our Top 10 Most Famous Medieval Paintings to Exist

The Medieval art period spanned over 1000 years and encompassed a diverse range of artistic movements. Many notable Medieval art examples stand out as there was a vast variety of art produced during that time. However, specific Medieval artists and their paintings have been recognized as instrumental for their masterful techniques and their contribution to the progression of art.

This is our selection of the 10 most famous Medieval paintings from the Medieval art movement.

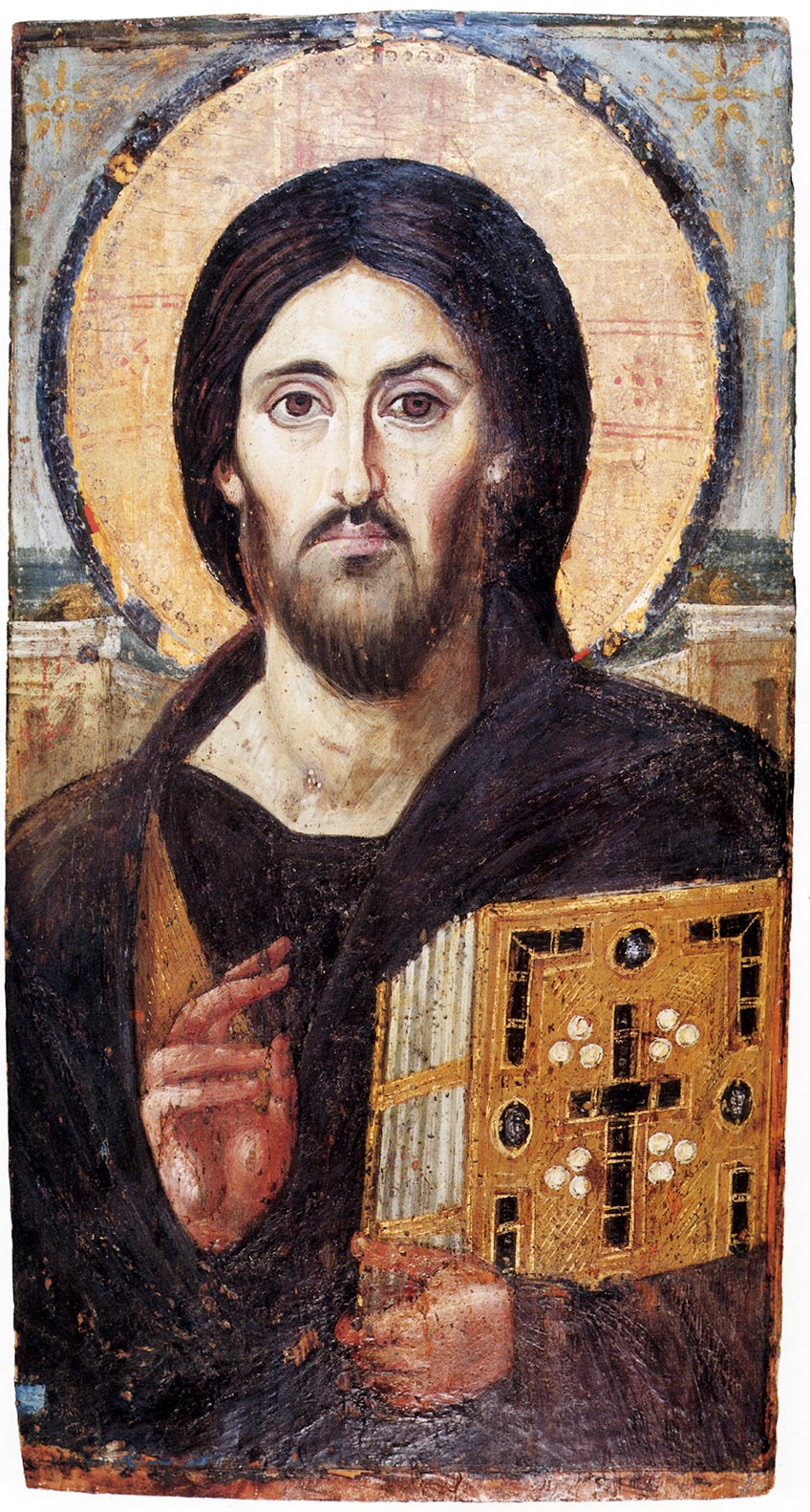

Christ Pantocrator (Sinai) (c. 500 – 600)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date Painted | c. 500 – 600 |

| Medium | Encaustic and gold on wood |

| Dimensions | 84 cm x 45.5 cm |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt |

Although a great deal is not known about the Christ Pantocrator (Sinai), this Medieval painting has been recognized as one of the oldest religious icons in the Byzantine style. The artist remains unknown, but the Christ Pantocrator, translated to mean “Christ the savior”, dates back to the 6th century. The painting depicts Christ with a raised right hand, which signified his gift of blessing, and in his left arm, he held a Gospel book that was decorated with jewels in the shape of a cross.

The painting is purposely asymmetrical, as it symbolizes the duality of Christ. The gold halo framing Christ’s head makes this more apparent. When looking at the depiction of Christ’s face, on the side where Christ holds the Gospel (the right side of the painting), Christ’s features are depicted as severe and hard.

This side was painted with more depth and shadow, illustrating a more three-dimensional representation of Christ with a sense of realism. This realism was representative of Christ’s human nature.

In contrast, on the side where Christ’s right hand is raised (the left side of the painting), Christ’s face is portrayed more serenely and calmly and this is representative of Christ’s divinity. Additionally, it is portrayed with more light and softness, and it is flattened to illustrate a two-dimensional representation. This absence of realism serves to highlight the spiritualization of Christ and His role as savior.

This icon is an important piece of art, being the earliest known piece of artwork in the Pantocrator style and one of the very few that survived the Byzantine Iconoclasm. The brilliance of the painting lies in the manner it seamlessly unifies the two halves of Christ’s face, depicting the Incarnate Christ as the union of both human and divine nature.

Lamentation (The Mourning of Christ) (1306) by Giotto di Bondone

| Artist | Giotto di Bondone |

| Date Painted | 1306 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions | 200 cm x 185 cm |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy |

Giotto di Bondone has been considered as one of the most important forerunners of the Renaissance. Giotto was an influential Italian artist from the late Medieval period, often referred to as the proto-renaissance. The Lamentation (The Mourning of Christ) has been recognized as one of his most notable works from the frescoes he painted for the Arena Chapel in Padua.

Giotto’s Lamentation (The Mourning of Christ) forms part of the fresco series used to depict the Life of Christ and the Life of the Virgin in the Scrovegni Chapel. The painting depicts the moment after Christ was crucified, where his lifeless body was tended to by haloed relatives and disciples. Where Mary, the focal point, cradled Christ’s head as Mary Magdalene mourned at His feet.

Giotto was able to bring his figures to life and convey their feelings through the fine details of their hands and feet.

Additionally, the positions of their bowed heads and opened mouths portrayed a deep sense of mourning and grief. Their gestures connote sympathy and devastation for Christ’s suffering. Not only did Giotto’s human figures depict a sense of emotional realism, but the foreshortened portrayals of the grieving angels and the use of diagonal lines for the mountain ridge brought a sense of physical realism to the composition.

Giotto decisively broke away from the Byzantine style and introduced the ground-breaking techniques of drawing accurately from life and according to nature. It strayed from the two-dimensional conventions and provided depth and naturalized figures. He focused on the quality of realness in art as he observed humans and reproduced their gestures, expressions, and movement in his art.

Giotto’s progressive artistry advanced naturalism, which later emerged as an important feature in Renaissance sculpture and painting.

Maestà (c. 1308 – 1311) by Duccio di Buoninsegna

| Artist | Duccio di Buoninsegna |

| Date Painted | c. 1308 – 1311 |

| Medium | Tempera and gold on wood |

| Dimensions | 370 cm x 450 cm |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Museo dell’Opera Metropolitana del Duomo, Siena, Italy |

Duccio di Buoninsegna, the founder of the Sienese School of Painting, was one of the greatest Italian painters from the Medieval period. The Maestà has been recognized as the greatest of all his works. The title Maestà meant The Virgin Mary in Majesty and this painting was part of a polyptych, therefore it formed part of an altarpiece made of many wooden panels.

The panels in the front depict the Madonna and Child enthroned and they are surrounded by saints and angels.

The Virgin Mary was garbed in an intense blue and the drape behind her was embroidered with gold, Duccio used exquisite colors in his panels. There were abundant decorative surfaces in the painting which was very distinctive of the Sienese style. Duccio painted the Maestà with a sense of delicacy and subtlety, this can be seen by the clothing that Christ was swaddled in and the transparency around his leg as a modulation of light and shadow.

Duccio created a sense of mass and volume, as seen by the left hand of Christ pulling the drapery towards himself with the folds molded into the drapery. You begin to see the three-dimensionality in the painting with the modeling of Christ’s chin and neck. Correspondingly, the angel’s wings are painted in a curled manner to further indicate a sense of volume rather than seeming flat.

In the Maestà, the figures of saints and angels are almost life-size. It is important to note the relative size of the Virgin Mary, she is the largest figure in the painting. This is because Mary had the paramount role of interceding between God and mankind, as she was used by normal people to access God.

The Medieval artwork produced by Duccio combined the formalized Italo-Byzantine tradition with the Gothic style’s conception of spirituality. This fusion brought a powerful spiritual gravity and lyrical expressiveness to his paintings.

Duccio steadily and consciously moved towards creating a sense of mass and volume in his painting which established a stylistic standard that influenced later artists.

Ognissanti Madonna (c. 1310) by Giotto di Bondone

| Artist | Giotto di Bondone |

| Date Painted | c. 1310 |

| Medium | Tempera on panel |

| Dimensions | 325 cm x 204 cm |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy |

Another painting by the influential artist Giotto di Bondone was his Ognissanti Madonna. The painting portrayed the Virgin Mary with the Christ Child, with figures of saints and angels surrounding them. Giotto’s rendering of the Virgin Mary was volumetric and convincingly realistic as opposed to the flat, linear, conceptual, and unrealistic depictions that were more typical of the Byzantine style in art.

Although this may be true, there were still some elements that were in line with the traditional methods of the time such as the golden background and the hierarchical layout of the figures. However, Giotto was able to create a seemingly measurable depth in his paintings through perspective and lighting.

Giotto painted naturalized figures that looked more human. In previous eras, the figures’ anatomy underneath their clothes was not detailed, whereas Giotto took care to subtly represent the impression of Madonna’s chest and knees through her clothes and Christ’s body through the robe he was draped in, which brought forth a sense of anatomical realism.

Giotto used architectural perspective to depict the throne and pictorial space that corresponded with reality, where the figures around the Madonna were smaller and obeyed the spatial rules of the scene. The raised position of the Madonna and Child symbolized their spiritual elevation. Yet it was made more realistic because of the throne on which they were seated and the steps leading up to it. Christ’s raised hand became the focal point of the painting and the surrounding figures that gazed at him encourage you to focus on him.

Although the Madonna was still enthroned as the Queen of Heaven, which was a typical Medieval depiction, Giotto’s inclusion of steps leading to her throne made her more accessible. This gives the illusion that she was part of the spectator’s world.

This was in line with the naturalism that would soon emerge as an important trait for Renaissance paintings going forward.

Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus (1333) by Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi

| Artist | Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi |

| Date Painted | 1333 |

| Medium | Tempera and gold on panel |

| Dimensions | 305 cm x 265 cm |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy |

Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi were Medieval painters from Italy who adopted the Gothic style in their artwork. Their painting Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus was a wooden triptych that was painted in tempera and gold. It has been considered as one of the most outstanding Gothic paintings and was recognized as Martini’s masterpiece. The triptych was painted as a side altar for the Siena Cathedral.

The painting depicted the Annunciation in the central panel, where archangel Gabriel, who was carrying an olive branch, knelt before the seated Virgin Mary and informed her that she would soon bear the child of God. Gabriel was depicted holding an olive branch which is traditionally seen as a symbol of peace. The vase on the floor between Gabriel and Mary was a symbol of purity. Above it, in the central arch, there were a group of angels whose wings interlocked, where the Holy Ghost’s dove had descended from heaven.

Latin words that translate to “Hail, Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee” were embossed in gold and extended from the angel’s mouth towards Mary.

Martini had detailed the wings of the angels and the chair where Mary was seated exquisitely, which gave the painting a sense of elegant and precise refinement. On either side of the central panel, the two patron saints of the cathedral were separated by two decorative twisting columns.

Martini’s central panel demonstrated his innovative utilization of line work combined with a sense of human expression and movement. The placement of the angel’s gown made it seem to flare behind him as if he had recently landed, and Mary was depicted in a stance that seemed quite reactive and emotive as if she was startled from her reading and in disbelief of the celestial messenger.

Although the substantial use of gold and the subject matter of the painting reflected the traditional Byzantine style, the linework was representative of the Gothic style.

In addition, the use of realistic elements such as the vase, the book, the throne, the pavement that was in perspective, the realistic depiction of the two figures, and the subtle nuances of their characters, all contributed to the significant detachment from the typical Byzantine style. This portrayal of Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus was unique for its time.

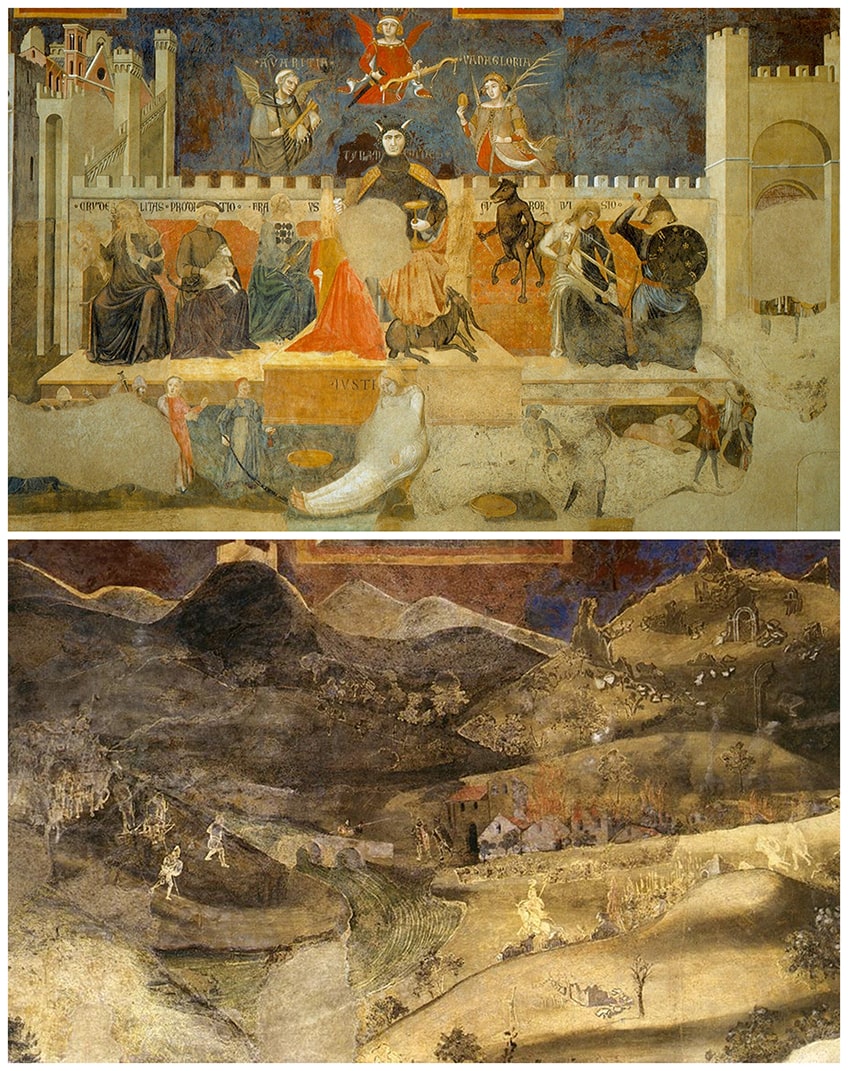

The Allegory of Good and Bad Government (c. 1338 – 1339) by Ambrogio Lorenzetti

| Artist | Ambrogio Lorenzetti |

| Date Painted | c. 1338 – 1339 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions | 770 cm x 1440 |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, Italy |

Ambrogio Lorenzetti painted The Allegory of Good and Bad Government as a series of three frescoes in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico in Italy. The frescoes consisted of six different scenes: Allegory of Good Government; Allegory of Bad Government; Effects of Bad Government in the City; Effects of Good Government in the City; Effects of bad Government in the Country; and Effects of Good Government in the Country.

This painting is considered to be Lorenzetti’s masterpiece.

The Council of Nine (the city council) commissioned the series in its entirety, this was recognized as a type of political message for the members of the Council to reduce misrule and corruption. The frescoes were secular depictions of symbolic figures of virtue, on how the republic was governed.

These paintings demonstrated an evolution in subject matter from earlier art that was predominantly religious.

The frescoes demonstrated a pictorial distinction between the harmony and prosperity of ruling honestly versus the ruin and decay resulting from tyranny. Lorenzetti’s portrayal of the benefits of good government was depicted by a “good city” which featured dancers and traders and surrounding the city, travelers and peasants conducted their business in harmony.

Whereas his portrayal of the effects of bad government was depicted by a “bad city” which was decaying, had a cramped appearance and street crime was distinctly visible. Surrounding the city, the countryside was marked by farms that were burning, disease, and extensive drought.

Lorenzetti’s paintings demonstrated his artistic modernism, as can be seen from his modeling of figures and their faces. Additionally, Lorenzetti’s paintings depicted realistic architectural angles and his use of primitive perspective allowed the spectators to perceive the physicality of his paintings.

Significantly, Lorenzetti’s The Allegory of Good and Bad Government was one of the first notable artworks that depicted political secular art since the period of classical antiquity. It has been said that Lorenzetti’s frescoes foreshadowed the moralistic scenes that were later created by the painters Hieronymus Bosch in his Garden of Earthly Delights and Pieter Bruegel in his Netherlandish Proverbs.

Crucifixion Altarpiece (c. 1394 – 1399) by Melchior Broederlam

| Artist | Melchior Broederlam |

| Date Painted | c. 1394 – 1399 |

| Medium | Tempera on panel |

| Dimensions | 167 cm x 249 cm |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Dijon, France |

Melchior Broederlam was one of the earliest Flemish painters. His Crucifixion Altarpiece is comprised of two panels. Broederlam was commissioned by the Duke of Burgundy to decorate the exterior of the altarpiece with two painted panels for the Chartreuse de Champmol. Broederlam’s Crucifixion Altarpiece has been recognized as a very famous painting to come out of the Medieval period.

The Crucifixion Altarpiece illustrated the Life of Christ: The Annunciation, the Visitation, the Presentation in the Temple, and the Flight into Egypt. Inside the altarpiece, the story continues with the Adoration of the Magi, the Crucifixion of Christ, and lastly Christ’s Entombment.

Broederlam’s panels have been recognized as magnificent examples of the Gothic style, as they featured rich colors such as gold and naturalistic detail such as his use of light and shadow to create depth. The architecture and figures were elegantly and delicately depicted.

The arrangement of the sacred buildings, which occupied two of the four scenes, was quite distinctive. Broederlam painted both buildings as open to the outside world as if he was trying to show both the interior and exterior at the same time.

This noticeable contradiction was a convention that was inspired by the Italian paintings from the 14th century.

In the Crucifixion Altarpiece, the pictorial elements were balanced in each panel and Broederlam arranged the figures, landscape, and architecture in a manner that created visual harmony. Moreover, the architectural structures in both panels were placed on the left, while the landscape was placed on the right side of each panel.

Correspondingly, the rocky landscapes reached the top of both panels and in the rectangular projection of each panel, the space was filled by an angel. These elements were tied together by Broederlam’s use of blue, pink, and red repeatedly on either side, which encourages you to move your eyes from one scene to the next. Thus, Broederlam expertly created a sense of continuity across the individual events.

The influence of Broederlam’s Italian counterparts from the 14th century was evident in his landscape depictions.

It was seemingly out of proportion with the surrounding buildings and figures. This was similar to what could be found in the Sienese School of Painting. It was evident that Flemish artists had been exposed to their Italian counterparts from the early 14th century. These encounters created an international style based on the art in Italy, which was soon equally found in Prague, Dijon, or Cologne.

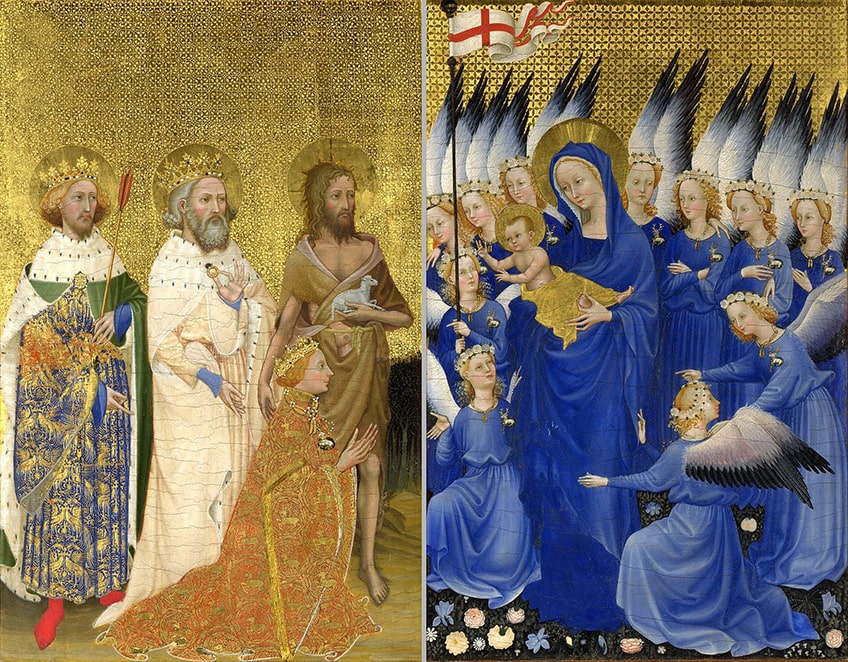

Wilton Diptych (c. 1395 – 1399)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date Painted | c. 1395 – 1399 |

| Medium | Tempera on panel |

| Dimensions | 53 cm x 37 cm |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | National Gallery, London, England |

The artist who painted the Wilton Diptych has remained unknown, but the highly revered painting is considered a rare masterpiece. The panel painting, made of oak, was a portable altarpiece that was made for the King of England, Richard II. It was used as a devotional piece to aid in prayer.

The painting combined secular and religious imagery.

When opened, the panel depicted the King kneeling before the scene of heaven. King Richard II was being presented by England’s patron saints Edmund and Edward the Confessor, and John the Baptist, to the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child, who were surrounded by eleven winged angels. The number eleven was significant because Richard II became the King of England when he was eleven.

The King’s hands were presented to either give or receive Saint George’s standard with the red cross. Christ’s hand was raised to bless the standard, along with King Richard’s II rule, as if the King was given the divine right to rule by the Virgin Mary and Christ Child.

The Wilton Diptych was painted in the International Gothic style. The refined detail of the painting is exceptional. The depiction of small-scale figures with their delicate facial features, and the robes they wore that fell in soft folds was intricately executed.

The painting is beautifully decorative and rich in colors of gold and ultramarine blue.

The depiction is abundant with symbolism, such as Saint George’s standard, the white hart badges that were worn by the King and the angels were representative of the King’s badge, and the rosemary in the flowers was emblematic of the King’s first wife Anne of Bohemia.

The Wilton Diptych is so significant not only because of the richness of the paintwork, or the meticulously tooled gilding, or the extraordinary detail; but it is a very rare English panel painting. The small altarpiece is only one of a few English panel paintings that survived from the Medieval period.

The Trinity (c. 1411 – 1427) by Andrei Rublev

| Artist | Andrei Rublev |

| Date Painted | c. 1411 – 1427 |

| Medium | Tempera on wood |

| Dimensions | 142 cm x 114 cm |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia |

Andrei Rublev was a Russian painter and his most famous work, The Trinity, was said to have been painted somewhere between 1411 and 1427. Various scholars suggest different dates, but officially it has been postulated that it was either painted in 1411 or from 1425–1427. The icon was commissioned for the Trinity Monastery of St. Sergius to honor Saint Sergius of Radonezh. The painting depicted three angels seated at a table, with a chalice placed in the center.

Rublev’s painting portrayed the angels who announced to Abraham and his wife Sarah that they would have a son. More specifically, the three angels represented the Trinity, as the unity of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Although God is not represented in The Trinity, the painting is still able to demonstrate an ideal expression of God.

The three figures purposely share identical features, as the Trinity is unified. This is where the belief is that God is one, but in three persons.

The painting is rich with symbolism. The unity of the Trinity was further indicated by the blue garments worn by each angel. The painting conveys that the three were engaged in a sacred discussion through gesture and gaze, and they surrounded the chalice which was symbolic of Christ’s sacrifice. Rublev’s arrangement of the angels, the fluid lines used, and his depiction of the angels’ clothing all contributed to the creation of a visual circle, which was symbolic of their unity. The circular composition imparts a sense of still contemplation.

As for Russian icons, “The Trinity” is recognized as the most famous interpretation. Rublev’s icon was declared as the model for all Russian Orthodox icons. The painting is considered one of the greatest achievements of Russian art from the late Medieval period.

Adoration of the Magi (1423) by Gentile da Fabriano

| Artist | Gentile da Fabriano |

| Date Painted | 1423 |

| Medium | Tempera on wood |

| Dimensions | 300 cm x 282 cm |

| Where It Is Currently Housed | Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy |

Gentile da Fabriano’s painting, Adoration of the Magi, has been recognized as his finest painting. The altarpiece was commissioned by Palla Strozzi for the Santa Trinita church’s family chapel. Adoration of the Magi depicted the travels of the Magi in various scenes. The scenes start in the upper left corner, which depicted the journey and entrance into Bethlehem.

The scenes continue in a clockwise formation, the lowest part of the painting portrayed the meeting between the Magi and Virgin Mary and the newborn Christ Child.

The vibrant colors in the painting are mesmerizing, which was due to the various ways in which gold leaf was applied and the use of precious pigments. The use of brilliant colors, intricate decorations, and opulent costumes were dominant in the International Gothic style. Fabriano’s work culminated in the International Gothic style of the late 14th century and early 15th century. Fabriano’s attention to detail was evident in his depiction of exotic animals, such as the leopard, the apes, the lion, and the spectacular horses.

While the architectural frame for the painting was constructed for a triptych, Fabriano abandoned the convention of dividing the painting’s composition. Instead, Fabriano spread the narrative across the panels.

The composition of the painting combined the splendor of Gothic details with naturalism. For example, the placement of some of the animals contributed to the illusion of depth, such as the varying angles of some of the horses in the foreground and the foreshortening of others. These features of physical realism alluded to the linear perspective and naturalism that later dominated the Renaissance.

The frame itself has been recognized as a work of art, which is demonstrated by the three cusps at the top of the panels with tondos. These are circular works of art that portrayed Christ Blessing in the center and the Annunciation, with the Archangel Gabriel on the left side and the Madonna on the right side.

Below the panels, the predella has three paintings depicting scenes from Christ’s childhood. This included the Nativity, Flight into Egypt, and the Presentation at the Temple. Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi was the first altarpiece that was made with panel and frame as two separate pieces, a fully independent and self-supporting frame, it was the first of its kind.

The paintings from the Medieval period continue to hold their weight to this day and remain influential works of art. Many paintings from this period went on to inspire great works of art in the years to come. While we have only explored 10 famous Medieval paintings, it is important to acknowledge that Medieval art is of great variety and there are many great works outside of our list. If you enjoyed learning about these exquisite paintings, we encourage you to continue exploring, as there are many art topics covered on our website.

We’ve also created a Google Web Story with our Top 5 famous medieval paintings.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Different Types of Medieval Paintings?

The different types of Middle ages paintings can be roughly classified into fresco, panel, and iconography painting. Medieval art examples included a large number of fresco paintings, which involved the method of mural painting, and this was completed on wet lime plaster. The majority of fresco paintings were created for the interiors of churches. Panel paintings were executed on flat, often wooden panels. They were predominantly featured in religious spaces, namely church altarpieces, depicting religious subjects. These devotional panel paintings were either diptychs made of two panels, triptychs made of three panels, or polyptychs made of multiple panels. Lastly, iconography painting was a significant type of Medieval painting and it incorporated the depiction of holy figures, biblical narratives, and religious concepts.

What Are Some of the Common Characteristics of Medieval Art?

Middle ages paintings varied quite a bit in style, but they were unified by a few common factors. These common characteristics included the importance of portraying Christian subject matter, along with the use of iconography to depict religious symbolism and imagery in Medieval artwork. Medieval painters included elaborate decorations and intricate patterns in their paintings, where a process called ‘tooling’ was used to imprint designs on the backgrounds of paintings which were often gold. When it comes to famous Medieval paintings, we often find that artists used bright colors such as the intense ultramarine blue, which was made from grinding lapis lazuli, a semi-precious stone, into a powder. Middle ages paintings often incorporated precious gems and metals.

What Was the Style of the Medieval Art Period?

The Medieval art period encompassed various artistic movements and styles. The major art movements included the Early Christian art movement, the Byzantine art movement, the Romanesque art movement, and the Gothic art movement. The Medieval art examples produced during the 13th and 15th centuries were predominantly in the Gothic style. This was regarded as visual art’s transitional period. Medieval artists and their paintings shifted away from the rigid formulas necessitated by Romanesque painting, which in itself had been largely influenced by the Byzantine style, towards a representation of the world that was more realistic and a desire to achieve a three-dimensional effect.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Famous Medieval Paintings – Exploring the Best Middle Ages Paintings.” Art in Context. September 13, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/famous-medieval-paintings/

Meyer, I. (2021, 13 September). Famous Medieval Paintings – Exploring the Best Middle Ages Paintings. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/famous-medieval-paintings/

Meyer, Isabella. “Famous Medieval Paintings – Exploring the Best Middle Ages Paintings.” Art in Context, September 13, 2021. https://artincontext.org/famous-medieval-paintings/.