Roman Mosaic – An Overview of Ancient Roman Mosaic and Tiles

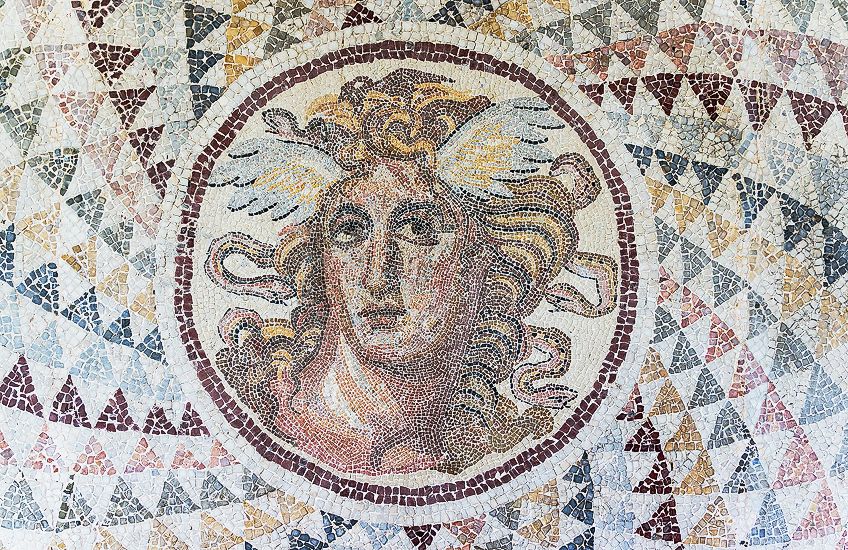

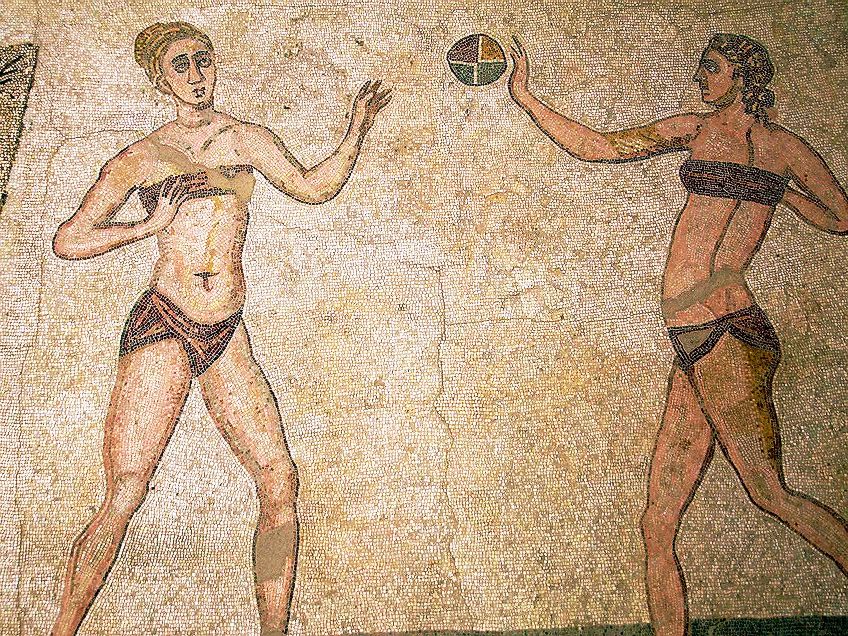

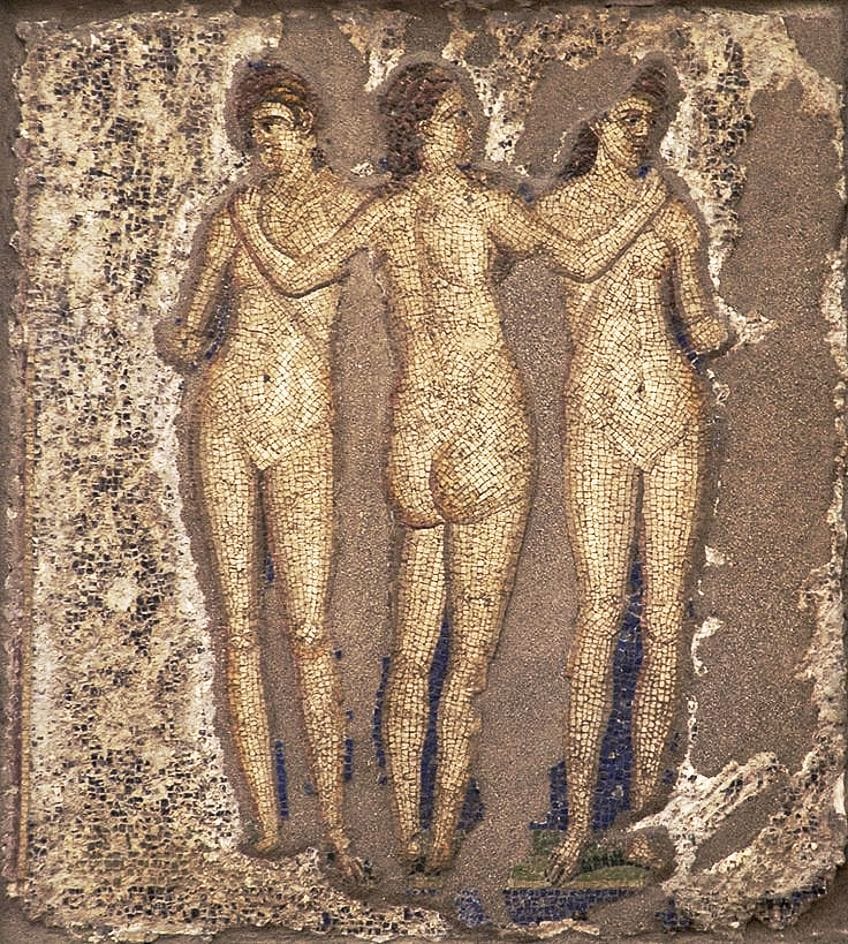

From Antioch to Africa, ancient Roman mosaic art was a ubiquitous component of private residences and public structures. Roman Mosaic tile art is not only stunning in and of itself, but it also serves as essential documentation of everyday objects such as clothing, foodstuff, tools, weaponry, vegetation, and animals. Roman mosaic floor artworks also disclose a lot about Roman pastimes like gladiator fights, athletics, farming, and hunting, and they occasionally even depict the Roman people themselves in vivid and lifelike portraits.

Ancient Roman Mosaic Art

The Roman patterns made of small white and black tiles are known as Roman Mosaic art. Glass, ceramics, stones, and even seashells were used to create these square tiles, with a fresh mortar base being initially constructed.

After, the tiles or tesserae were placed as close together as feasible, with any gaps plugged with liquid mortar in a procedure called grouting. The entire thing was then washed and polished.

Influences and Origins

During the Bronze Age, both the Minoans and the Mycenaeans employed flooring made of tiny pebbles. A similar concept, but with repeating motifs, was utilized in the Near East in the eighth century BCE. The first attempts at pebble paving in Greece date back to the 5th century BCE, including specimens at Olynthus and Corinth. They were often two-toned, with light geometric motifs and basic figures on a black background.

Colors were being utilized by the close of the 4th century BCE, and numerous good instances have been discovered in Pella in Macedonia.

These mosaics were frequently strengthened by inlaying pieces of clay or lead, which were frequently employed to delineate contours. However, it wasn’t until the Hellenistic period in the 3rd century BCE that mosaics truly took off as a form of art, with elaborate panels made of tesserae instead of pebbles being mixed into patterned flooring. Many of these mosaics tried to imitate wall murals.

As mosaics advanced in the second century BCE, finer and more accurately cut tesserae were used, and patterns utilized a broad range of colors with colored grouting to complement adjacent tesserae.

This form of mosaic, which employed intricate coloration and shading to produce a painting-like impression, is known as opus vermiculatum, and one of its best artisans was Sorus of Pergamon, whose work, particularly his Drinking Doves mosaic, was widely replicated for years following.

Aside from Pergamon, notable specimens of Hellenistic opus vermiculatum have been discovered in Delos and Alexandria. Because of the time and effort required to create these pieces, they were placed on a marble tray or bordered tray in a specialized workshop. These items were called emblemata because they were frequently utilized as centerpieces for pavements with simpler motifs. These pieces of art were so precious that they were frequently relocated for re-use somewhere else and passed down through generations within families.

A single mosaic might be made up of several emblemata, and as time passed, the emblemata developed to imitate their environment, and they were known as panels.

Design Evolution of Roman Patterns and Motifs

With a topic like mosaics, it’s impossible to depict a precisely linear growth of the art form since there’s so much variation in artistic excellence, public preference, and regional norms. However, certain significant differences and geographical differences can be identified.

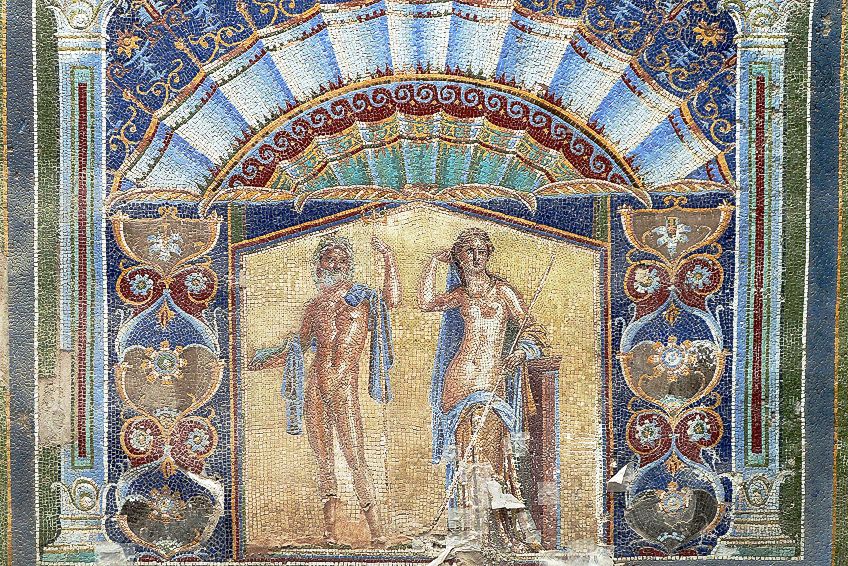

At first, the Romans did not deviate from the Hellenistic attitude to mosaics, and they were strongly swayed in regards to the subject matter – sea themes and depictions from Greek mythology – and the creators themselves, as many signed ancient Roman mosaic art contain Greek names. This demonstrated that even in the Roman period, Greeks controlled mosaic design.

One of the most well-known Roman mosaic tile artworks, The Alexander Mosaic, for example, was a replica of a Hellenistic classic artwork by either Aristeides of Thebes or Philoxenus. It is part of the Pompeii mosaics, located at the House of the Faun.

Although Roman mosaics frequently copied earlier colored ones, the Romans eventually developed their own designs, and manufacturing schools were established throughout the empire to nurture their own specific tastes.

These included large-scale hunting sequences and efforts at perspective in the African regions, painterly vegetation, and a foreground viewer in Antioch mosaics, or the European personal taste for figure panels, for instance.

The main Roman style in Italy itself employed solely white and black tesserae, a taste that lasted far into the third century CE and was most frequently used to portray aquatic motifs, particularly when used for Roman baths ( for instance those that are located on the first floor of the Baths of Caracalla.) There was also a penchant for two-dimensional depictions, with a focus on geometric patterns.

The oldest depiction of a humanoid figure in mosaic artwork is found at the Baths of Buticosus in Ostia around 115 CE, and silhouetted figures were popular in the 2nd century CE.

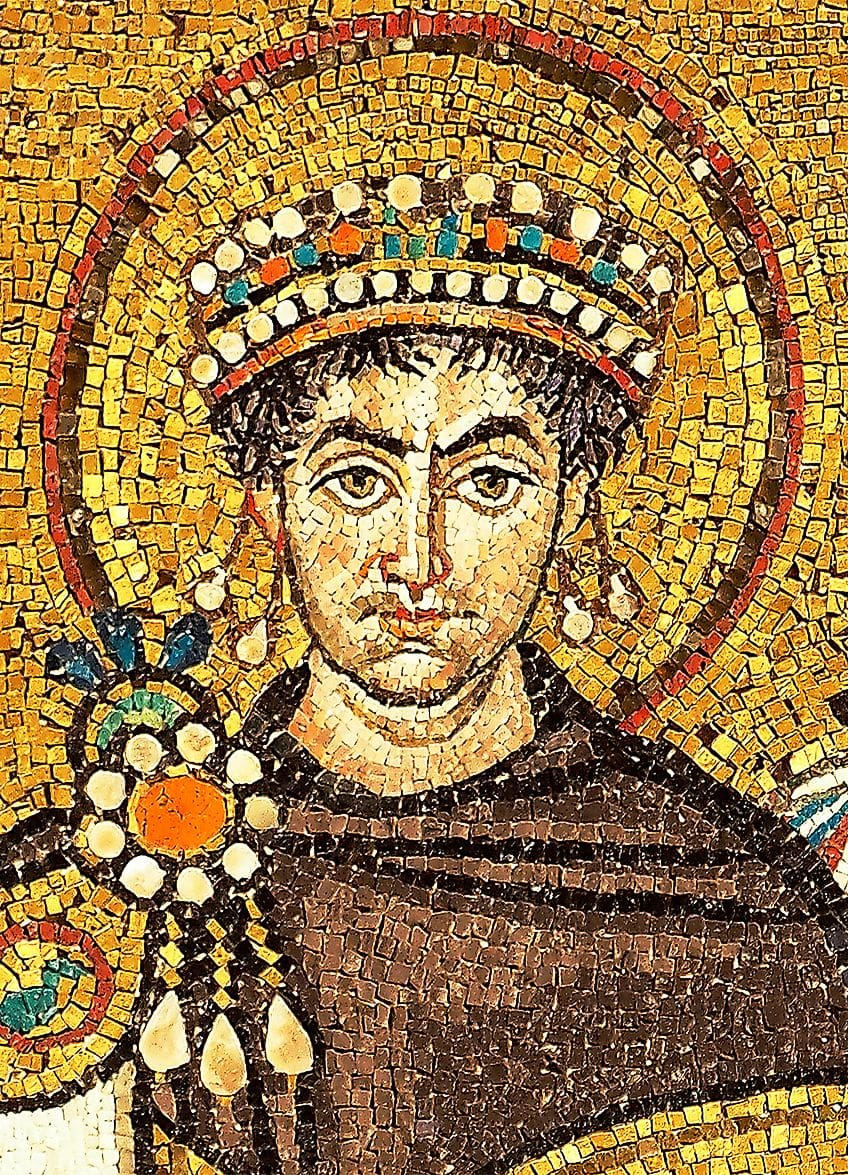

Over time, the mosaics’ depictions of human beings got more lifelike, and precise portraits became more widespread. Meanwhile, in the eastern half of the empire, particularly Antioch, the 4th century CE saw the emergence of mosaics that employed two-dimensional and repeating patterns to produce a “carpet” impression.

This style would go on to profoundly influence subsequent Jewish synagogues and Christian churches.

Other Roman Mosaic Floor Designs

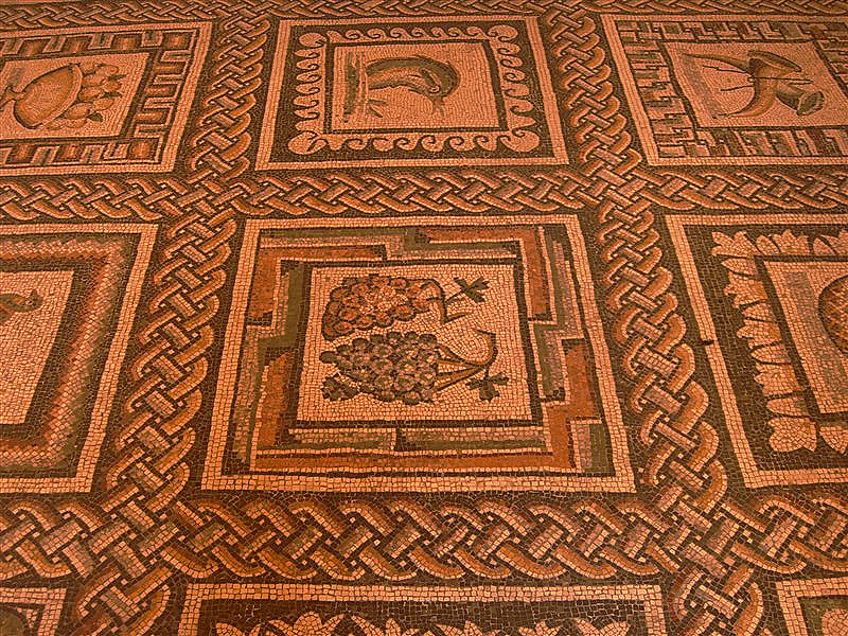

Floors might also be placed with bigger pieces to create greater-scale patterns. Opus signinum flooring was made of colored mortar-aggregate (typically red) and white tesserae that were set in wide patterns or even randomly.

Crosses with five red tesserae and a center tessera in black were a popular pattern in Italy in the first century BCE and remained until the first century CE, but with only black tiles.

Opus sectile was a form of flooring that employed huge colored marble or stone slabs carved into certain shapes. Opus sectile was another Hellenistic method, although the Romans also used it for wall design. Although it was used in many public structures, it wasn’t until the 4th century CE that it became increasingly widespread in private villas.

Following Egyptian influences, opus sectile started to employ opaque glass as the major material.

Mosaic’s Other Uses

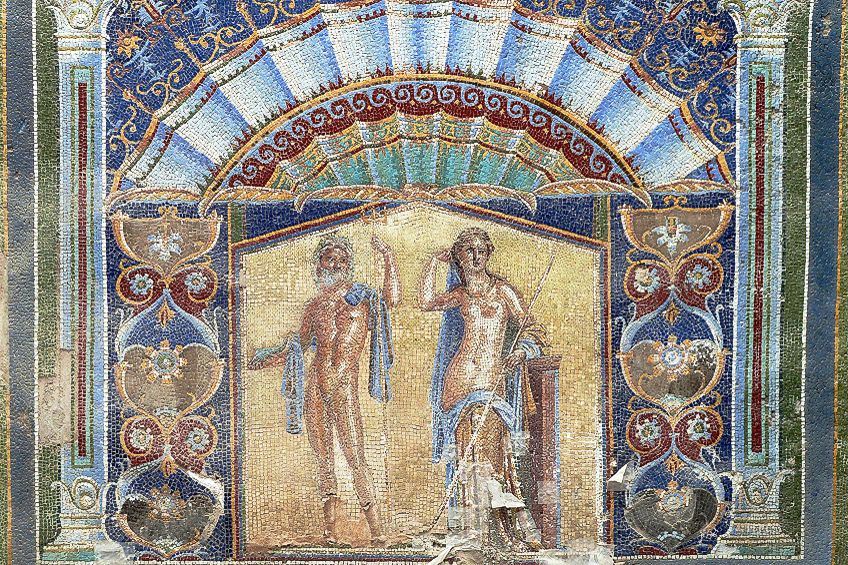

Mosaics were not just used on floors. columns, vaults, and fountains were frequently adorned with mosaics, particularly in baths. The first example of its use may be found in the nymphaeum of the “Villa of Cicero” at Formiae in the mid-1st century BCE, when pumice, marble, and shell fragments were utilized. In other places, bits of glass and marble were placed to create the illusion of a natural grotto.

More intricate mosaic panels were also utilized to adorn Nymphaea and fountains by the 1st century CE. The method was also utilized with the Pompeii mosaics to cover walls and pediments, and these murals often mimicked real paintings.

Later Imperial Roman baths’ walls and vaults were also adorned in mosaic utilizing glass, which worked as a reflector of the sunlight striking the pools and provided a shimmering appearance. The flooring of pools was frequently decorated with mosaic, as were the floors of mausolea, which occasionally included an image of the dead.

The Roman utilization of mosaics to embellish wall space and vaults influenced internal decorators of Christian churches beginning in the fourth century CE.

The Pompeii Mosaics

For more than 2000 years, historians, archeologists, and visitors have been enthralled by Pompeii and its devastation. Pliny the Younger’s manuscripts, which were lost beneath debris until unearthed in 1748, included information on a major volcanic eruption that rocked the Bay of Naples. The conventional date of the Mount Vesuvius eruption in 79 CE, although the current study has been conducted to revise this date, even down to the specific day.

The volcano erupted, burying the Bay of Naples, particularly Pompeii, in a thick layer of ash and detritus, functioning as a protective blanket over the people, structures, and materials of the site.

Because of the chemical composition of the volcanic ash and its unique qualities, archeologists have discovered nothing less than a perfectly intact Roman metropolis during the height of the Roman Empire over the last 250 years.

While much has been written on the incredible preservation and castings of remains, the Pompeii mosaics are equally as beautiful and merit their own in-depth examination.

Plato’s Academy Mosaic

Plato’s Academy mosaic is a near-perfectly maintained mosaic. This mosaic, which dates from the first century BCE or just before the eruption, is housed in the home of T. Siminius Stephanus. A group of seven people is depicted in the tile.

It is supposed that Plato is at the head, yet correctly identifying one of the characters as Plato is very difficult, as no differentiating feature of rank is indicated.

The Cave Canem Mosaic

The Cave Canem mosaic, or “Beware of the Dog,” is perhaps one of the most fascinating mosaics to a new audience. The well-preserved mosaic was installed at the entryway of the Tragic Poet’s House. An extremely lifelike dog, displayed in active motion as if about to attack, baring teeth and wearing a leash and chain around its neck, is overlaid over a background of repeated diamonds and carries the words “CAVE CANEM” in Latin.

This is the first thing guests would have seen when they entered the house, and it is similar to any current sign put on a fence or door declaring the same thing. A stunning cast of a dog trapped in the disaster may be found among the ruins of Pompeii. While this dog was not the one represented in the mosaic, it did wear a collar and was most likely a pet.

While these three mosaics are not the only ones that survived at Pompeii, they are among the more intriguing and engaging. Mosaic installations were extremely frequent kinds of decorating, although we seldom find this level of near-perfect preservation.

Looking at these mosaics reveals the aesthetic interests of the residents at the time, as well as the topics that were essential in their everyday lives. Ongoing excavations at the Pompeii mosaics continue to find architectural components such as terraces and allies, as well as corpses, frescoes, texts, and mosaics, revealing even more significant insight into everyday life in the Roman Empire.

Ancient Roman mosaic art was a common feature of private homes and public constructions from Antioch to Africa. Not only is Roman mosaic tile art beautiful in and of itself, but it also provides an important record of everyday goods like clothes, food, tools, armament, greenery, and animals. Roman mosaic floor artworks also reveal a great deal about Roman activities like gladiator battles, sports, farming, and hunting, and they occasionally portray the Roman people themselves in vivid and lifelike images.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Origin of Roman Mosaic Floors?

During the Bronze Age, both the Minoans and the Mycenaeans used pebble floors. In the seventh century BCE, the Near East used a similar design, but with repeated themes. The first attempts at pebble pavement in Greece date back to the 5th century BCE, with examples found at Olynthus and Corinth. They were frequently two-toned, with light geometric designs and simple forms set against a black backdrop. These mosaics were usually reinforced by inlaying clay or lead bits, which were commonly used to outline shapes.

How Are Roman Mosaic Tiles Made?

Roman mosaic art refers to Roman designs consisting of tiny white and black tiles. These square tiles were made from glass, pottery, stones, and even seashells. A new mortar base was first constructed, and then the tiles or tesserae were placed as close as possible together, with any spaces plugged with liquid mortar in a practice called grouting. After that, the entire item was cleaned and polished.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Roman Mosaic – An Overview of Ancient Roman Mosaic and Tiles.” Art in Context. March 7, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/roman-mosaic/

Meyer, I. (2022, 7 March). Roman Mosaic – An Overview of Ancient Roman Mosaic and Tiles. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/roman-mosaic/

Meyer, Isabella. “Roman Mosaic – An Overview of Ancient Roman Mosaic and Tiles.” Art in Context, March 7, 2022. https://artincontext.org/roman-mosaic/.