Orientalism Art – When the West Romanticized the East

We all know the story of Aladdin, a romantic depiction of Oriental life with flying carpets, magical lamps, and beautiful desert settings. While this may sound quite picturesque, this is all a fantasy and only a hint of cultural perceptions about Orientalism. In this article, we explore how the West has met the East and its place as Orientalism art history within the broader context of European art. The two are quite interlinked, and maybe not as symbiotic as we might think.

Table of Contents

- 1 Romancing the East: What Is Orientalism?

- 2 Orientalism Art: Depicting a European Concept

- 3 Famous Oriental Paintings

- 3.1 Napoleon in the Plague House at Jaffa (1804) by Antoine Jean Gros

- 3.2 La Grande Odalisque (1814) by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

- 3.3 Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1834) by Eugène Delacroix

- 3.4 The Snake Charmer (c. 1879) by Jean-Léon Gérôme

- 3.5 The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1860) by William Holman Hunt

- 4 Orientalism: Coming to an End?

- 5 Frequently Asked Questions

Romancing the East: What Is Orientalism?

Let us recalibrate our perspective of the term “Orientalism” because as a concept it carries considerable political weight. For us to have a better understanding of Orientalism art we need to ask some important questions that will provide context. As is often the case, art and politics are like two sides of the same coin.

Below we will look at the Orientalism definition and aim to explore a variety of questions. What is Orientalism, and what are the deeper meanings underneath this term? Where and how exactly did the term Orientalism originate?

It is also important to note that we will utilize the terms “East” and “Oriental” to refer to specific places like the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia. We will refer to Europe and North America as the “West”. These terms will be utilized for the purposes of creating context and understanding between the two major “divisions” throughout history, and in no way are utilized for pejorative or biased purposes.

Orientalism Definition

If we look at the Orientalism definition from the online Merriam-Webster Dictionary, it states the following: “scholarship, learning, or study in Asian subjects or languages” it continues to state that these are now “often used with negative connotations of a colonialist bias underlying reinforced by such scholarship”.

The actual term “Orient” also plainly refers to the geographical Eastern parts of the world, namely, the Middle East, which comprises the Arab world with countries like Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Turkey, among others, and the Asian continent. A vast territory is covered on the world map.

“Orient” also originates from the Latin word oriens, which connects to the meaning of “rising” and “dawn” and ultimately meaning the “East”. The Old French orient shaped what we now know as the “Orient”. The opposite term for Orient is Occident, which refers to the West or Western world that comprises countries like Europe, America, and Australasia. The term also derives from Latin roots referring to the meaning of “setting”, in other words, the sunset.

Throughout history, the term Occident also inherited a pejorative meaning attached to colonialist ideologies and how the West created a perception of the East. We will explore this in more detail below.

Appropriating the East: Edward Saïd

An important figure in Oriental discourse, or really discourses that touch on the concept of the “Other” was the Palestinian-American Edward Saïd. He was a professor and scholar and laid the foundations of what we now understand as Postcolonial studies. He was involved in various academic fields and taught within the English and Comparative Literature faculties at prominent universities like Columbia University and Harvard. He also taught at Yale University and Stanford and reportedly lectured at over 200 universities worldwide.

Additionally, he has been a part of numerous associations and boards and published his widely acclaimed book titled Orientalism in 1978. This has been an important book critically discussing the relationship between the West and East and the way the West perceived and ultimately interacted with the East as the “Other”.

Saïd explores different concepts in his text, for example, power structures and the idea of hegemony. This is in relation to the Oriental and Occidental, and ultimately, its division as perceived by the world. Not merely a geographical categorization, but a political and cultural division.

Think in a way the Occident has power over the Oriental, and Saïd also pointed to the idea of this power coming from Imperial forces. The way colonialism overtook other cultures and how the main ideas still run beneath the surface even though the landscape has significantly changed.

The “Other” – in this case, the Oriental cultures like the Arabs – have been seen as passive and docile people. However, Saïd questions this assumption. Furthermore, he holds up a mirror to the West and its action of lowering the status of one to make it seem in control.

The way the West portrayed the Orient is also more stereotypical than realistic.

An important point to note is that Saïd did not invent the term “Orientalism” and that this was already part of scholarly discourse. He merely started a discourse around the way the “West” in their own way appropriated the “East” and made it into something other than what it truly was and is.

Orientalism Art: Depicting a European Concept

Although Saïd’s text is considerably more complex than what has been explained above and worth reading for avid theorists and scholars interested in Orientalism art history. The main point to consider while we explore Orientalist artwork is the underlying current of power structures, and what we could possibly posit as an over-eager curiosity of the East, which both distort the reality of culture and makes it appear as something else.

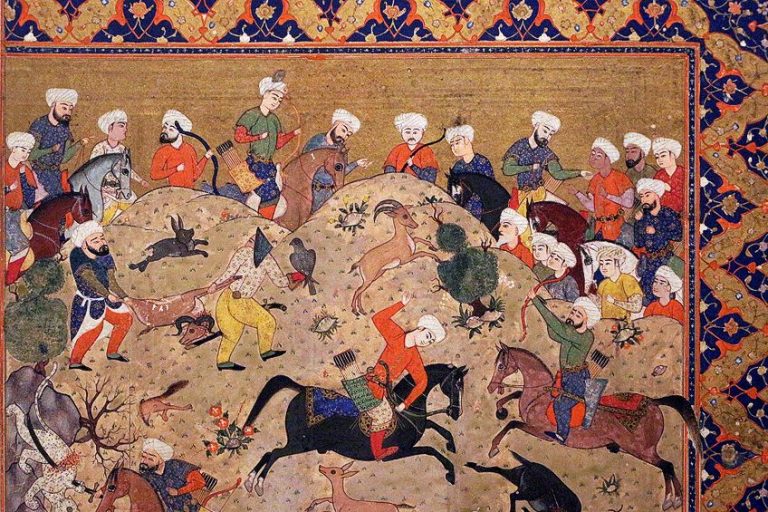

Orientalism art is a European concept, as we know, and it was popularized during the 19th century by various Oriental artists, as they were called.

These artists depicted the East and its places, people, cultural objects, religion, and everyday customs in their paintings. It often appeared romantic and quite fantastical but became a visual record of other lands and cultures mainly for the European and North Americans who were interested in these places.

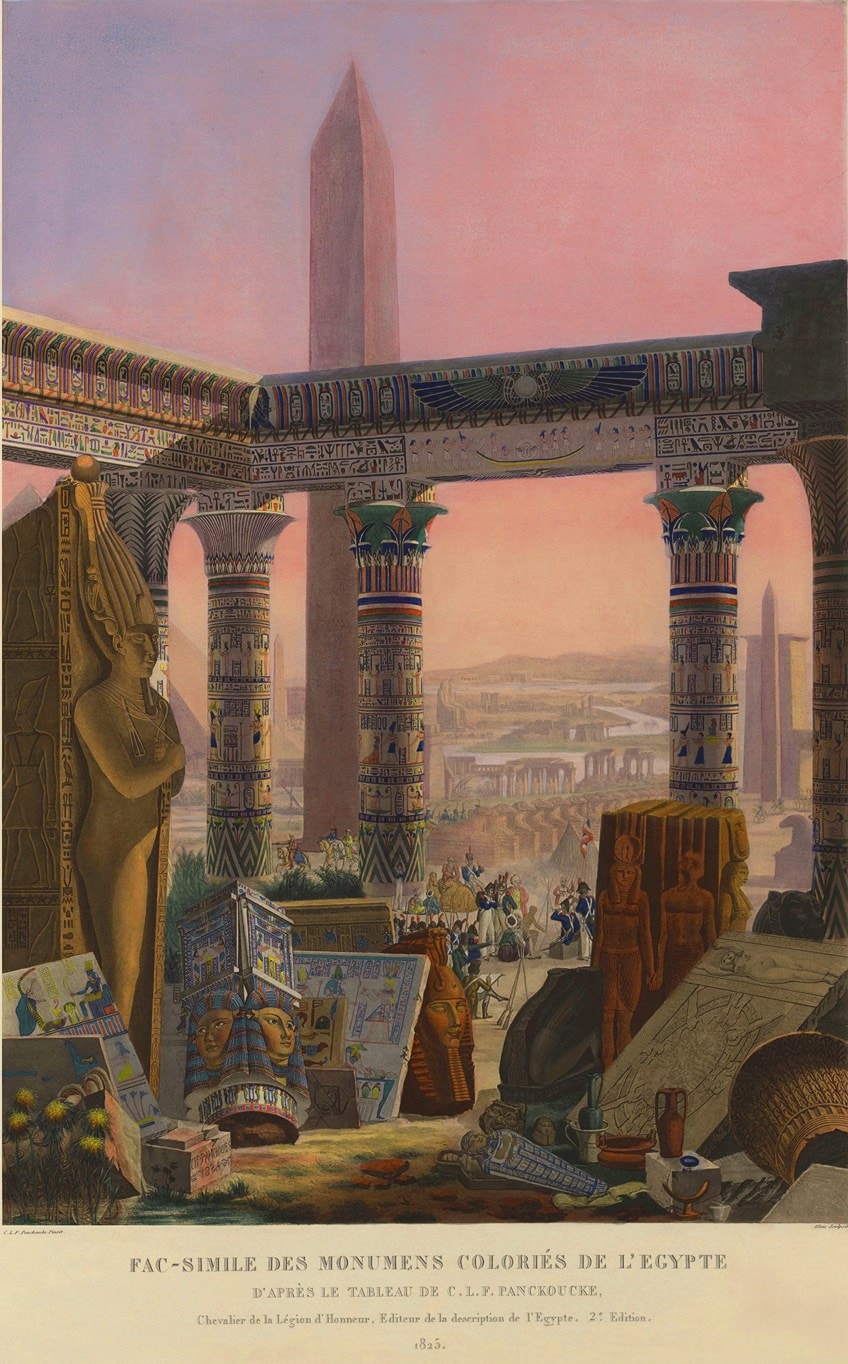

Orientalist art mostly gained traction after Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Egypt in 1798 and took over until 1801. This conquest created a surge in cultural dissemination from Egypt and other nearby places like the Middle East and the Levant, which presently comprises regions of Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Israel.

Numerous French artists started traveling to the East after Napoleon’s invasion and created visual records, paintings, and drawings of the newly found landscapes and their peoples. Oriental artists painted mostly in Genre paintings like everyday scenes, cultural objects, and places like harems. Religious paintings were also prominent and allowed artists to portray Biblical scenes with a sense of reference.

Numerous French artists were also referred to as “armchair Orientalists” because they never traveled to the East and did not have first-hand accounts of their subject matter. They would paint scenes from the information given to them and from their imagination.

There are also two important publications worth mentioning that placed Egypt and the wonders of this new world in the spotlight. These are, namely, one published by the French government, titled Description de l’Égypte (1809 to 1822). This was composed of 24 volumes and acted as a catalog of almost all things to do with Egypt, its history, culture, and environment.

Another important book was by Baron Dominique Vivant Denon, a French scholar, diplomat, author, and archaeologist, the latter profession he utilized when he traveled to the Middle East alongside Napoleon. He published a consequent book titled Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Égypte pendant les campagnes du Général Bonaparte (“Voyage in Upper and Lower Egypt During the Campaigns of General Bonaparte”, 1802).

Artists were also commissioned to paint for Napoleon, for example, Antoine Jean Gros who painted Napoleon in the Plague House at Jaffa (1804) and Battle of the Pyramids (1810). However, these paintings were propagandist tools to shine the spotlight on the political powers of the time, French Imperialism, and ultimately place the “Orientals” as a culture that was weaker. In other words, the East could be compared to a wild animal that the West wanted to tame.

Furthermore, Oriental artists portrayed the East from a heightened sense of imagination and easily slipped a false image of the licentiousness of the East into the pockets of art enthusiasts, which is a topic that has been widely critiqued. We see this in the famous oil painting titled The Snake Charmer and His Audience (c. 1879) by Jean-Léon Gérôme, who was a French painter and sculptor from the Vesoul.

Gérôme was highly admired and criticized for his Oriental paintings; he portrayed imaginative scenes with great artistic skill as if the scene were real.

Meanwhile In Europe

The landscape back in Europe looked considerably different during this time and is important to understand alongside the landscapes of the Middle East and North Africa. France, specifically Paris, during the 19th century had prominent art movements like Academic art, which was a component of the French Academy. The French Academy started in 1648 and created a “hierarchy of genres”.

The hierarchy of genres consisted of an order that started with History painting, Portraits, Genre painting, Landscapes, and the last genre was Still Life painting.

It was a tight-knit association and artists needed approval from the members of the Academy if they wanted to exhibit their paintings, furthermore, artists who were members were able to have work in the art field.

If we go back to the Academic art mentioned above, it was a style that portrayed art in a realistic manner, but also with a set of aesthetic rules, based on ideas of rationality and order, the Neoclassical art movement was similar.

Although this is a brief overview of these art styles and organizations in Paris, including Europe because the Academies were also in London and Italy, it is to highlight that the art institutions were quite structured, orderly, and conservative.

Art was made according to rules and, if we view Orientalism art from this perspective, it provides a clearer context partly for why it was created.

Orientalism art was also popular in Victorian (or British) art with pioneers like the Scottish David Wilkie, who worked in London. He was popular and well regarded for his genre paintings. He traveled to Jerusalem and Istanbul during the last years of his life.

In 1893 the Société des Peintres Orientalistes Français (Orientalist French Painters Society) was established for French artists. It aimed to provide artists the opportunity to travel to the East and to have a platform for Orientalism art exhibitions.

It was founded by the French painter Alphonse-Étienne Dinet and the French curator and art historian Léonce Bénédite, who was also the President of the society. Other members were Algerian painters, including the above-mentioned Jean-Léon Gérôme and others like Jean Maurice Bompard, Paul Leroy, and Eugène Girardet. The Salon held annual exhibitions displaying Orientalist artwork, but the society was proactive in shedding light on Oriental art and making it a genre too, also creating various publications.

Beyond publicizing Oriental art, the society was also in support of the proliferation of colonialism in places like the Middle East and North Africa.

Orientalist artwork also inspired artists within the art style called Romanticism. However, Oriental art was almost a subset within this style as it included various genres and artists. Well-known Romantic and Neoclassical artists reveled in Oriental art, for example, Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. However, Ingres did not travel to the East.

Famous Oriental Paintings

Below we mention a few of the popular paintings by Oriental artists, what their subject matter consisted of and the genres they painted in; we will also look at their stylistic approaches. Some paintings were more lurid than others and some paintings depicted the East with genuine awe and reverence of the cultures and customs. Let us jump right in.

Napoleon in the Plague House at Jaffa (1804) by Antoine Jean Gros

This painting by Antoine Jean Gros is also titled Napoleon in the Pesthouse Jaffa and Napoleon Visiting the Pest House in Jaffa. It is described as a proto-Romantic painting by Gros who also studied under the Neoclassical artist Jacques-Louis David but became a precursor to the styles of artists like Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix, these are all well-known artists’ names.

Gros was also known as an artist who depicted the military campaigns undertaken by Napoleon and as mentioned above, Napoleon conquered Egypt in 1798, which led to a new perception of the East.

Gros was commissioned by Napoleon to depict him whilst visiting several of his troops who were infected with the Bubonic Plague. This scene allegedly took place on 21 March 1799 in the Israelian city called Jaffa at the Armenian Saint Nicholas Monastery, where the soldiers were housed.

The composition depicts the French leader Napoleon Bonaparte as the central figure, he is clad in his military garb reaching out with his left hand (our right) at a man’s armpit area where he is infected, the man holds up his right arm for Napoleon to touch his sore.

Napoleon is furthermore surrounded by various figures; some have cloth wrappings around their bodies while others are in the nude, especially the man on his knees in the foreground of the composition appearing to gaze towards Napoleon while a doctor works on a sore by his left armpit (our right).

Behind Napoleon we see another soldier clad in military garb holding up a white cloth to his mouth; his expression appears more frightful than that of Napoleon’s seemingly nonchalant facial expression. This is really what the entire painting aims to depict, which is Napoleon’s fearless demeanor as a French leader as he fearlessly touches the sores of his soldiers his reputation is placed in good stead for the public to see.

This painting was created for propagandist purposes as it was meant to show the French leader in a good light. However, according to real-life accounts or rumors, he poisoned the infected soldiers with Opium.

The background depicts an architectural structure reminiscent of a mosque. We notice the horseshoe arch to the far left and then three pointed arches, the far-right arch only shows us a third of it. There are more arches as our gaze moves out of the foreground interior space, which suggests a courtyard in the center of the building. In the far distance, we also notice a rising hill with smoking buildings on it.

Gros painted in softer tones and shades with the central figure of Napoleon standing in a more lighted area of the interior. Religious symbolism is indicated by how Napoleon is depicted as a sort of “savior” to the sick and by touching their wounds he has this air of imperviousness. What Gros also did was to relay a religious theme in the likeness of a modern-day person, namely Napoleon.

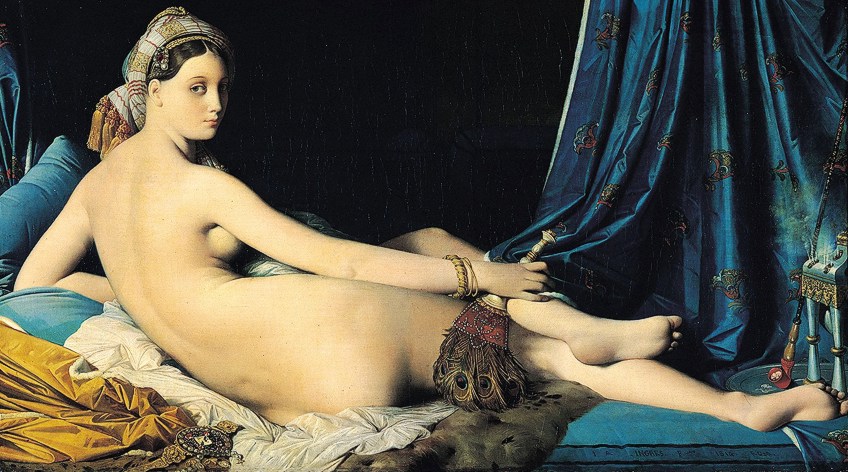

La Grande Odalisque (1814) by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

In La Grande Odalisque by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, we see a reclining woman gazing over her right shoulder at the viewer; her back is facing us. She is depicted completely nude wearing only a turban with a large broach attached to what appears like a golden headband. On her right wrist, there are three golden bracelets, and she holds an elaborate fan made of peacock feathers in her right hand.

There are various objects around her that give the indication that this is an Orientalist painting and that she is a wealthy woman.

Most importantly, she is depicted as an odalisque, which, to the French culture at the time, meant concubine. She is lavishly depicted with soft materials around her like the patterned damasks to the right and golden satins on the divan she lies on.

To the right are several pipes for smoking, this is referred to as a hookah. These pipes would be used for smoking either tobacco, opium, or hashish. Near the middle of her back, there is what appears to be a mirror placed facedown, this too is decorated with various jewels.

Ingres did not travel to the Middle East and was commissioned by the Queen of Naples, Caroline Murat, to paint this scene.

The odalisque we see here is reminiscent of the beautiful nude Venuses from mythological paintings, which were one of the primary subject matters for paintings during the time. However, Ingres gives the female nude a new setting, an Oriental setting. Furthermore, it also makes gazing at a female nude an acceptable act for the male viewer, similarly compared with Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1534) or Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus (1510), among others.

Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1834) by Eugène Delacroix

In Delacroix’s oil painting the Women of Algiers in Their Apartment we witness four women. To our far left we see a woman in a reclining pose staring straight at us, the viewers, with a peculiar gaze we might add.

The other two women, more centrally placed, sit on the floor appearing engaged with one another, both are smoking from a hookah, also called a Turkish water pipe. To our far right, we notice a black female figure, possibly a slave, in a standing position with her back to the viewers and her head is slightly tilted looking back as if she was just called.

The interior space is lushly decorated, and we see various objects and hints suggesting these women are courtesans. For example, the previously mentioned hookah and the loose clothing worn by the women.

Furthermore, this painting is rendered with an accurate eye to detail and ethnographic detail. Delacroix visited Tangier, a Moroccan city, in 1831. He joined the diplomat Charles de Mornay and company, who were sent by King Louis Phillipe, as the artist of the group.

Delacroix created many sketches and watercolors from his travels, ranging from décor, interiors, objects, and people. This allowed him to paint Women of Algiers in Their Apartment with cultural accuracy. His painting has also been described as less lurid than Ingres’ La Grande Odalisque for example.

Delacroix also created a sense of warmth with his combination of colors and shading. We see a source of light to the left entering the space, which is itself depicted in soft reds and yellow tones.

The space is not too bright, and Delacroix creates an ambiance by this more shaded interior space, highlighting corners, folds, and crevices in darker shades.

Delacroix also created a second version of this painting from 1847 to 1849, which is housed in the Musée Fabre located in Montpellier in France. The first version of 1834 is housed in the Louvre in Paris. The women in the second version are described as having a more inviting disposition than the women depicted in the first version, especially the reclining woman depicted to the left; her gaze is softened.

The Snake Charmer (c. 1879) by Jean-Léon Gérôme

The Snake Charmer is another, somewhat controversial, Oriental painting, by Jean-Léon Gérôme. What made the painting more controversial was its use as the cover of Edward Saïd’s book. It sparked further questions about the painting’s colonialist themes.

The artist painted this in considerable detail, as was his custom.

We see a scene with a nude boy as the central figure standing on a small rug with his back towards us. He is holding a python coiled around his body, its head held up high in his outstretched left hand and its tail in his right hand. We see the snake’s basket to the boy’s left and a man playing the flute to the boy’s right.

In front of the boy, we notice ten enrapt men, all dressed in and holding Islamic gear and weapons, sitting with their backs against a decorated, blue-tiled wall. The blue tiles are believed to originate from Iznik ceramic, which is from the Anatolian town called Iznik.

Gérôme did travel to the Middle East, and it is reported that when he returned, he painted from the multitudes of photographs taken during his trip, the subject matter of his paintings also, undoubtedly, co-mingled with his imagination. What we see in this painting is a representation of snake charming that occurred in Egypt and Turkey and not exactly where he would have been able to experience it.

The American art historian, Linda Nochlin, wrote about the realism that Gérôme painted in, which also made his paintings appear as if they were taken from real-life accounts. In her seminal essay titled The Imaginary Orient (1983), she poses the question of how we can understand this painting in terms of this realism and whose reality it really is.

Nochlin writes: “Surely it may most profitably be considered as a visual document of nineteenth-century colonialist ideology, an iconic distillation of the Westerner’s notion of the Oriental couched in the language of a would-be transparent naturalism”.

The boy’s nudity has also been debated, but sources suggest this was done during snake charming shows to avoid any fraudulent charges; the nudity would have been to show that there was no cheating during the show. Some also suggest that Gérôme depicted the subject matter in this composition in a lurid manner.

Nochlin describes the mood of the painting as a “mystery” and rightfully so, as we are drawn into a world imagined. She also states that the entire composition includes not only the central figure of the boy, but the onlookers too, and “our gaze is meant to include both the spectacle and its spectators as objects of picturesque delectation”. In one of his articles from 2012, the British art critic, Jonathan Jones, described this painting as a “sleazy Imperialist vision of the “East” and a “glitteringly cinematic slice of orientalist fantasy”.

In fact, this painting could be considered a fine art example of the idealistic and often distorted perception the “West” had of the “East”.

The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1860) by William Holman Hunt

In William Holman Hunt’s The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1860), we see a Biblical scene taken from the Gospel of Luke (2:41) when Mary and Joseph find Jesus in the temple among Jewish teachers and elders. To the right of the composition are Jesus, a young boy, Mary who is saying something in his ear, and Joseph behind the two. Jesus’ body is faced directly towards us.

Making up most of the left of the composition we see a group of Jewish men sitting and standing. They appear in conversation and eager discussion and Jesus is looking straight ahead at us.

There are also other objects that indicate significant symbolism, for example, the doves symbolizing the Holy Spirit, the man sitting outside the temple, he has a characteristic beard and appears to be praying, he symbolizes the Messiah. The boat in the background, with several men around it, symbolized the 12 Disciples.

Hunt was known to portray scenes with a naturalistic style, for example, scenes taken from scripture.

Hunt’s own religious beliefs inspired him to paint this scene. The artist also founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which consisted of English artists who took on the painting style from the Renaissance Quattrocento period. This would also explain the naturalistic style of his paintings.

Orientalism: Coming to an End?

Although Orientalism in art was seen as early as the Renaissance era, it grew and gained significance during the 19th century, however during the later years of the 19th century other prominent art movements like Impressionism and Post-Impressionism gained traction and Orientalism phased out.

But what about our Contemporary era? Is Orientalism still a “thing”, as they say? Contemporary artists have used Orientalism to pose important ideas about the concept and to “reframe” it. Examples include Houria Niati who is from Algeria and Lalla Essaydi from Morocco. Others include Huma Bhabha who creates sculptures, for example, “The Orientalist” (2007). There are many more contemporary artists who touch on and subvert the ideas we have come to understand about Orientalism.

Take a look at our oriental art web story.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Orientalism Art?

Orientalism art is a European concept and was popularized during the 19th century by various Oriental artists, as they were called. These artists depicted the East, its places, people, cultural objects, religion, and everyday customs in their paintings. It often appeared romantic and quite fantastical but became a visual record of other lands and cultures mainly for the European and North Americans who were interested in these places.

Who Are Famous Oriental Artists?

While there have been numerous artists during the 19th century depicting Oriental subject matter, some of the popular Oriental artists include, Antoine Jean Gros, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Léon Gérôme, William Holman Hunt, Gustave Moreau, Horace Vernet, Jean Discart, and numerous others.

What Are Armchair Orientalists?

Numerous French artists started traveling to the East after Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798 and created visual records, paintings, and drawings of the newly found landscapes and its peoples, but there were also many French artists who never traveled to the East and did not have first-hand accounts of their subject matter. They would paint scenes from the information given to them and from imagination – they were referred to as “armchair Orientalists”.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Orientalism Art – When the West Romanticized the East.” Art in Context. December 20, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/orientalism-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 20 December). Orientalism Art – When the West Romanticized the East. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/orientalism-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Orientalism Art – When the West Romanticized the East.” Art in Context, December 20, 2021. https://artincontext.org/orientalism-art/.