Byzantine Art – Traversing the Byzantine Empire Art Period

Byzantine art, which developed as a branch of the Roman Empire, was mainly distinguished by a move away from naturalism within Classical Art towards a more abstracted and worldwide look. The Byzantine empire spanned more than one thousand years and included works created during the 14th and 15th centuries. Seen as a significant period in the development of Western art, Byzantine art went on to create incredibly well-known sculptures, paintings, and mosaic works that are still talked about today.

Table of Contents

What Is Byzantine Art?

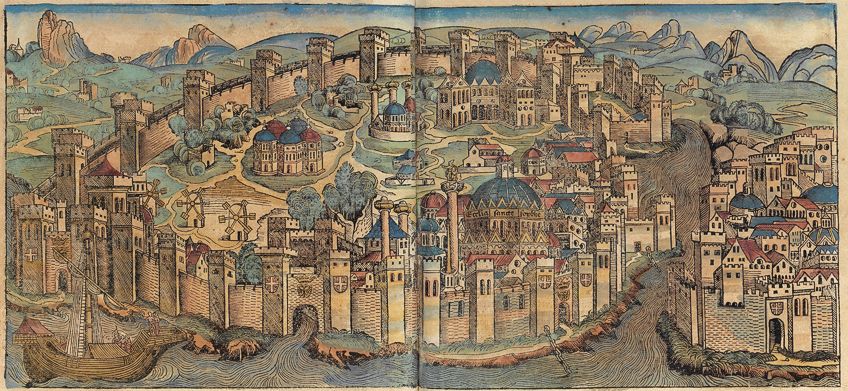

The term “Byzantine art” originated from the Byzantine Empire, which was said to have initially developed from the Roman Empire. In 330 A.D., in what is now known as Turkey, the Roman Emperor Constantine formed the city of Byzantion as the new capital city of the Roman Empire. Originally an ancient Greek colony, Byzantion was Latinized by the Romans to be called Byzantium, until its name was changed to Constantinople.

Byzantine art was traditionally comprised of Christian Greek artworks that came from the Eastern Roman Empire, as well as other nations that were culturally influenced by it. States that were impacted by the style of artworks developing within the Roman Empire were part of the Byzantine Commonwealth, which encapsulated many nations demonstrating the characteristics of Byzantine art. Some states that used these characteristics but remained separate from the Byzantine Empire were the Republic of Venice and the Kingdom of Sicily.

Classifying artworks as Byzantine art proved to be a bit tricky, as the Byzantine Empire and its artistry went on to exist for over a millennium.

During its reign, the Byzantine Empire moved away from Constantinople and expanded far and wide, meaning that the artworks created during this period of time stretched past the Italian peninsula and into the Middle East and Northern Africa. Countries that still maintain elements of Byzantine art today include Greece, Cyprus, Bulgaria, Romania, and Russia.

The Byzantine art period went through many political, social, and artistic disruptions. Byzantine architecture and art are generally divided up into three phases, namely the Early Byzantine era, the Middle Byzantine era, and the Late Byzantine era. Intrusions into this artistic period were the result of the Iconoclastic Controversy and the Latin Occupation, which both went on to leave a noticeable influence on the development of Byzantine art.

The Byzantine Empire persisted until the fall of Constantinople in 1453. The movement was credited with producing some of the most notable icon paintings, frescoes, mosaics, illuminated manuscripts, sculptures, enamel work, and church architectures ever seen, of which some are still visible today. Many states went on to preserve aspects of the empire’s culture and art for centuries afterward, with the characteristics of Byzantine art even being used in the new Ottoman Empire that emerged after.

A History of Byzantine Art

The Byzantine art era, which spanned between 330 to 1453 A.D., existed as an incredibly important movement within art history. While some critics have understated the prominence of Byzantine art, believing it to not be as famous as the Italian or Northern Renaissance, the movement greatly influenced the creation of artworks and sculptures, with its style still in existence today.

Byzantine Empire art was known for its lavish mosaics and excessive use of gold, as the artworks made were said to be in response to the rise of Christianity in Europe.

Byzantine art emerged after the Roman emperor, Constantine the Great, reassigned the ancient imperial capital from Rome to Byzantium, which was renamed the city of Constantinople in his own honor. Roman artisans were moved to the city so as to decorate the Christian churches with a variety of ancient Roman mosaics, as Emperor Constantine had finally declared tolerance for Christianity.

Constantinople was also referred to as the “New Rome” due to the city’s newly discovered standing as the political capital of the Roman Empire. Inhabitants of the city were Greek-speaking Christians, who deemed themselves to be Romans and thus the inheritors of the ancient Roman Empire. Byzantine art thus originated from the Christianized Greek culture that existed in the Roman Empire, with elements of both Christianity and classical Greek mythology being artistically expressed in the artworks that were produced.

As the Byzantine Empire developed, an essential aspect of it was that it was much more Greek than Roman in many ways. Thus, Hellenistic art and the concept of naturalism went on to influence the production of art during this time. This led to Constantinople, the heart of the Byzantine Empire, to be viewed as the focal point of art history at that point, which helped disseminate the style’s works, methods, and ideas throughout the Empire.

Known to be the Eastern branch of the Roman Empire in its initial stage, Early Byzantine art had a strong Roman and Classical influence. Artists adopted various Roman traditions when creating art, such as the process of collecting and displaying artworks in private to the exclusive wealthier classes of Byzantium who were thought to appreciate art more. However, as the Byzantine art movement began to evolve, themes that were once considered very important within Roman and Classical art began to be reworked and altered.

One of the most significant themes that began to change as Byzantine art continued to develop was the depiction of conventional religious scenes.

As the Byzantine era went on, religion continued to exist as a dominant theme in the traditional artworks made, but a closer inspection of these individual works revealed the ever-changing approach to art that was employed. Despite the Byzantine art movement signifying a move away from Classical art, religion as a definitive theme prevailed in the artworks made.

By the 12th century C.E., Byzantine art had become a lot more suggestive and inventive in spite of the subject matter staying the same. Due to this, the vast majority of the surviving Byzantine Empire Art pieces have demonstrated religion to be one of the most dominant themes throughout the period. As an empire, Byzantine art continued to expand and shrink over the centuries, as the era was greatly influenced by the influx of new ideas that came from other parts of Europe.

As most pieces coming from this period contained a predominantly religious message, Byzantine artwork was mainly used to decorate churches throughout the Mediterranean. Byzantine art was largely characterized by abstraction and a two-dimensional representation, as artists attempted to generate a universal appeal for their artworks.

The various ideas and art objects of the Byzantine Empire were constantly spread between different cultures in Europe through royal gifts, religious missions, and movements of the artists themselves.

Byzantine art demonstrated a great focus on an impersonal interpretation of church theology into artistic terms, which were mainly seen in the architecture, paintings, mosaics, frescoes, and sculptures that came from this period. The outcome of emulating religion as a rigid tradition rather than on a personal whim resulted in a sophisticated style of art to develop, with the spirituality and expression of Byzantine art rarely equaled in later art periods.

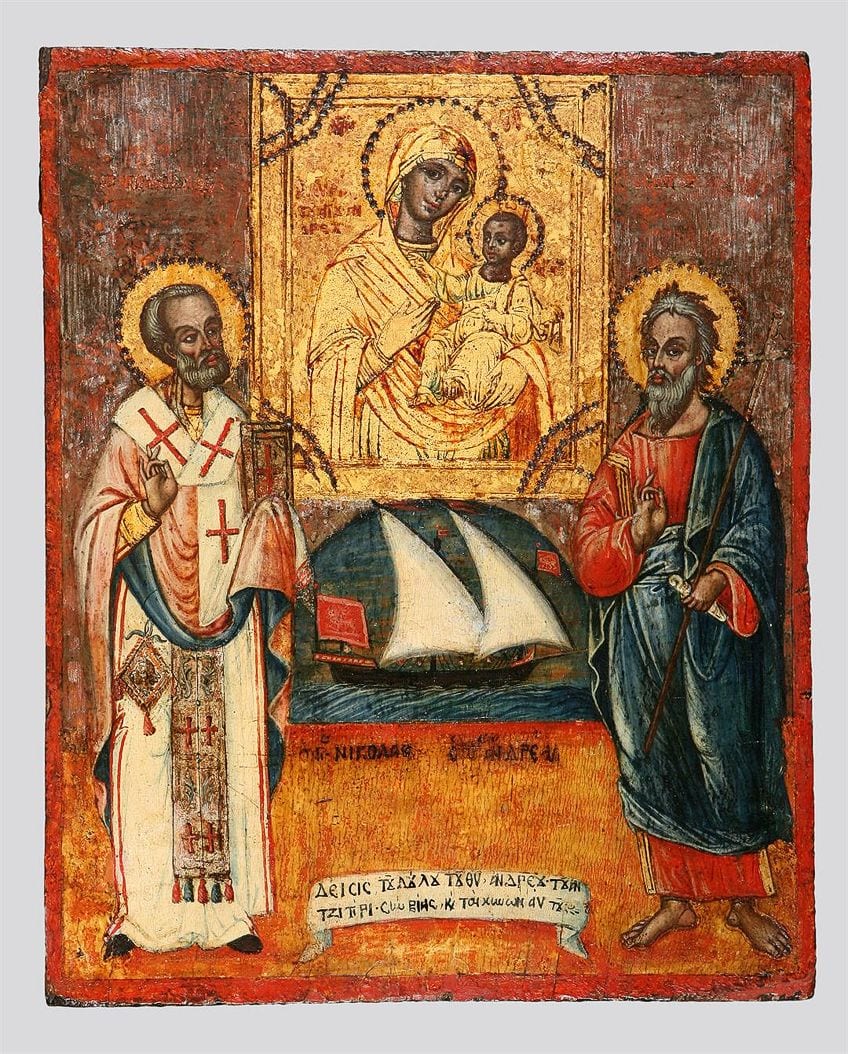

Artists within the Byzantine era beautified almost everything that they came into contact with. Various buildings, books, and most notably, Christian churches, were all decorated using bright stones, gold mosaics, carved ivory, precious metals, and spirited wall paintings and frescoes. Representations of icons, like Christ, the Virgin Mary, or specific saints, were used to adorn churches and private homes in an attempt to manifest the figure itself and its holy presence. This technique became one of the typical characteristics of Byzantine art.

These techniques of Byzantine art can still be seen in certain Christian churches around the world today, as the importance of religious art within the Byzantine era was monumental. Artistic ideals circulated to important outposts like Sicily and Crete, where the inclusion of Byzantine iconography into the artworks that were being produced would go on to become formative influences on the later development of the Italian Renaissance.

The style of Constantinople art that emerged from the Byzantine Empire flourished for hundreds of years and spread throughout what is now present-day Spain, Italy, and Turkey. Byzantine art continued until the 15th century when the city of Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Empire.

Despite this bringing the movement to a close, certain artworks produced during the Ottoman Empire were labeled as “post-Byzantine” due to the characteristics used, which demonstrated the lasting effects that this period had on the history of Western art.

Periods Within the Byzantine Era

Lasting until 1453 A.D., art and architecture that emerged from the Byzantine Empire can generally be split up into three historical periods that have been labeled as Early Byzantine art, Middle Byzantine art, and Late Byzantine art. However, a disruption in the continuity of the Byzantine Empire occurred between the last two periods by the Latin Occupation.

Early Byzantine Art (circa 330 – 750 A.D.)

In 330 A.D., Roman Emperor Constantine adopted Christianity as the prevailing religion and switched his capital city from Rome to Constantinople. This religious shift drastically affected the type of art that was created in the Empire, as Christianity began to replace the Greco-Roman gods of antiquity that previously defined Roman religion and culture. Considered to be the first golden age of the new Empire, the Early Byzantine art period extended well into the 700s while Christianity’s culture and religion diversified the state.

The practice of Christianity, which developed in the 4th century, spread throughout the entire Byzantine Empire and was an important influence on the art created. Throughout the Early Byzantine period, Constantine devoted a great effort to the adornment of Constantinople and decorated various public spaces with ancient statues. The following ruler, Emperor Justinian, saw to this and oversaw the building of iconic Constantinopolitan churches, with the most famous example being the original foundations of the patriarchal cathedral, the Hagia Sophia.

Early Byzantine art centered around Roman law as well as Greek and Roman culture so as to sustain a carefully controlled government.

This led to the artistic traditions of the affluent state extending throughout the empire and into other provinces entirely, such as those in North Africa. However, as the art period advanced, the Byzantine Empire was subject to intrusions by various Western territories over the decades, which introduced a whole host of other influences to Early Byzantine art.

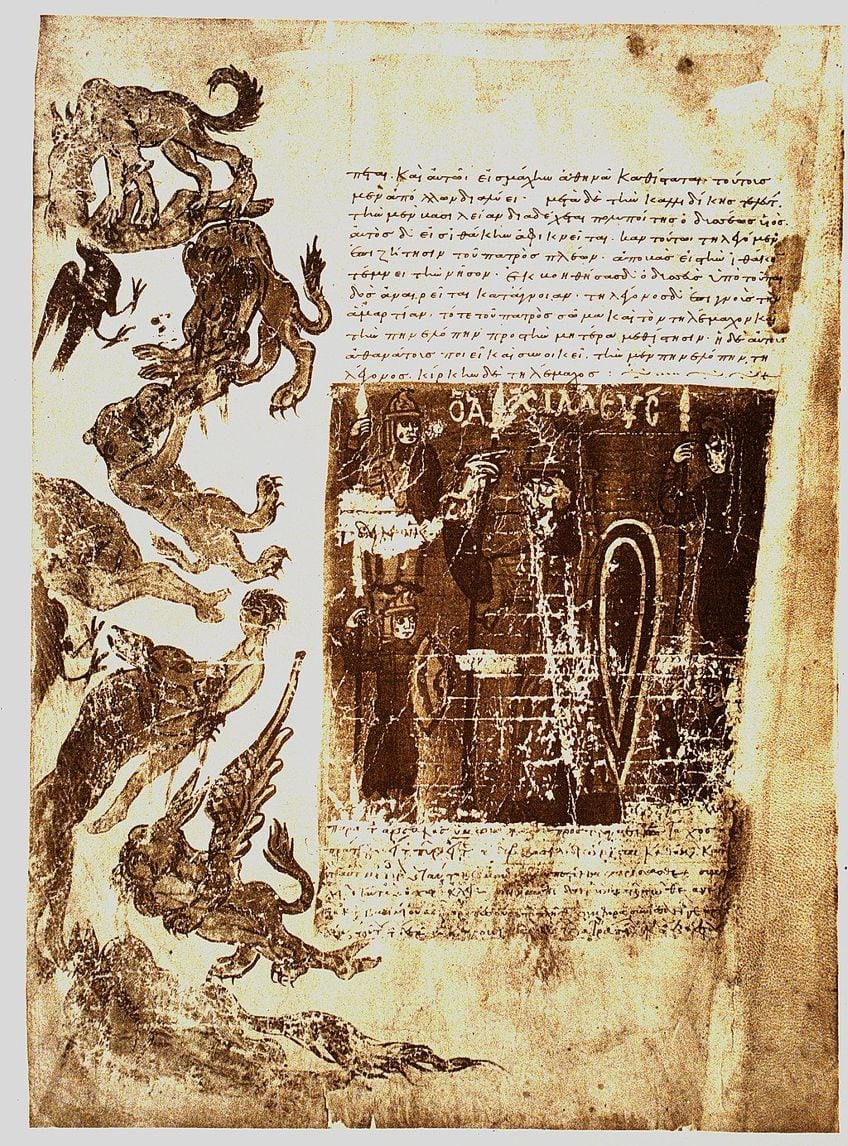

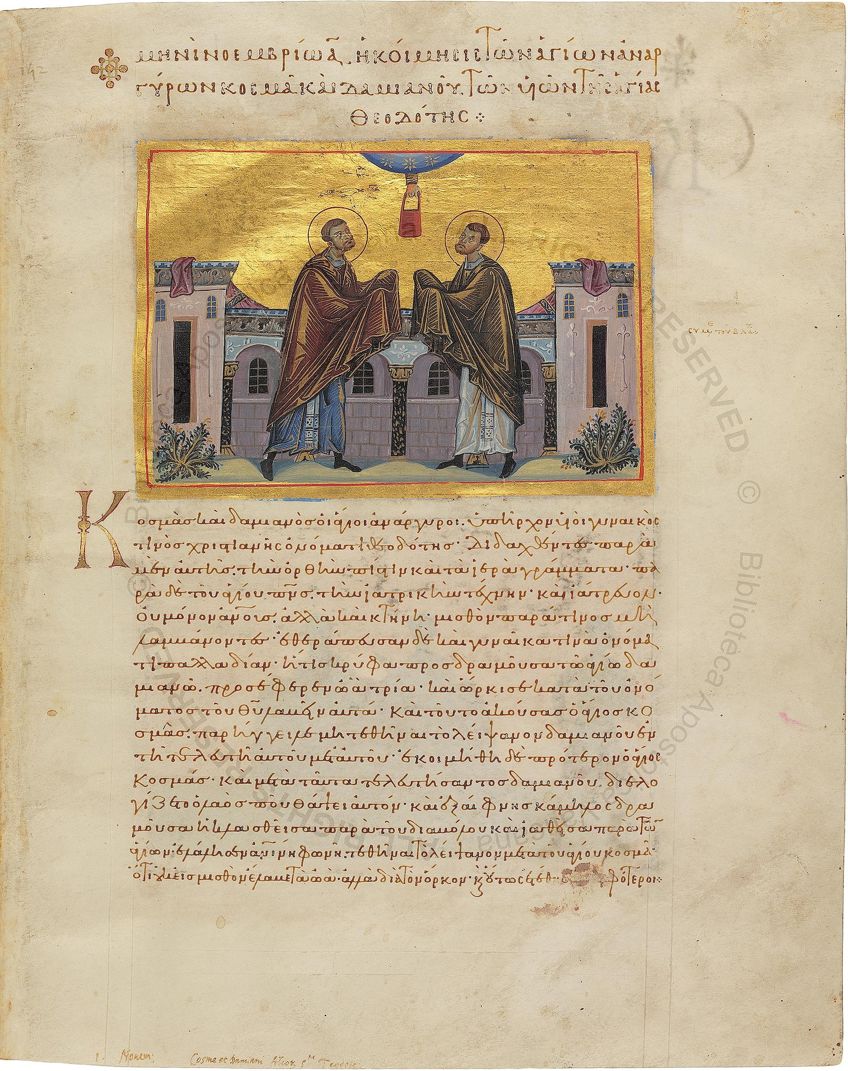

Important artworks, such as decorations for the inside of churches like icons and mosaics, as well as illuminated manuscripts, exist as some of the most notable Byzantine pieces to survive this era. An iconic manuscript to outlive this time period is Homer’s Iliad, which is considered to be one of the oldest works of Western literature today. Unfortunately, very few Constantinopolitan monuments from this period remain, yet the influence of Early Byzantine art can be seen in the surviving structures in other cities.

Middle Byzantine Art (circa 850 – 1204 A.D.)

After a brief period of the Iconoclastic controversy, which favored the proper use of icons, breaking out at the end of the first Byzantine period, the Middle Byzantine art era emerged. Following a great stage of crisis, which destroyed much of the images that developed in the Early Byzantine period, the stylistic and thematic interests of the period continued into the Middle Byzantine art phase.

A greater focus was placed on the building of churches and decoration of the interior, which brought some changes to the Byzantine Empire.

The most notable change was that Greek became the prescribed language of the Byzantine state and church, as Christianity extended from Constantinople to the Slavic regions of the North. This led to the adoption of Orthodox Christianity by Russia in the 10th century, as the influence of Byzantine art had given new inspiration to the Slavic land.

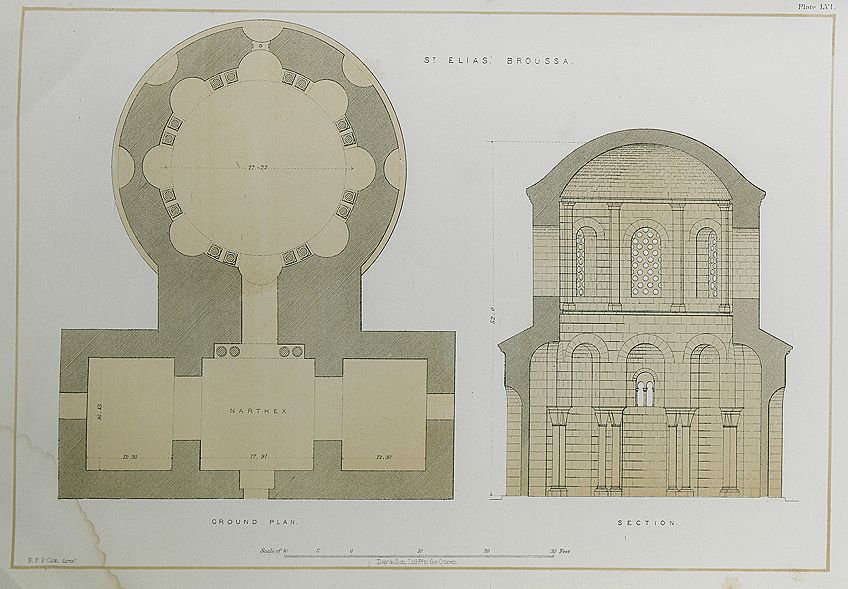

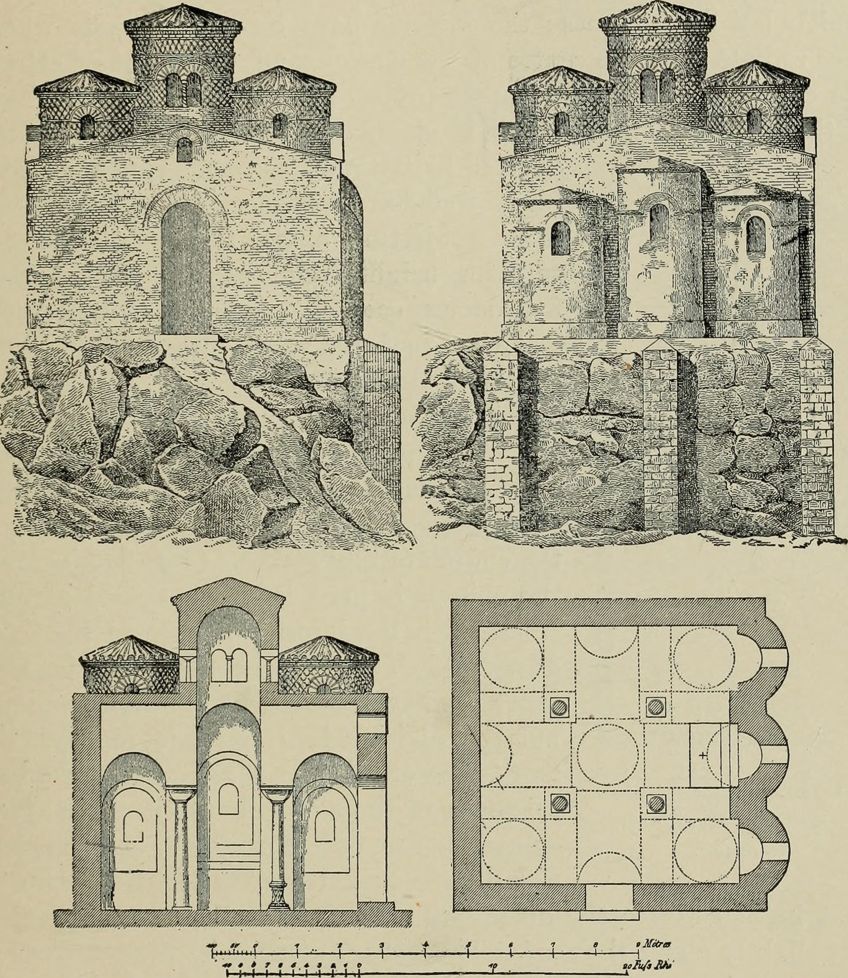

Byzantine art and architecture began to flourish during the Middle Byzantine art period as a result of the Empire’s increasing wealth and foundation of rich art patrons. Architecture during this phase moved towards the centralized cross-in-square plan, which is what Byzantine architecture is best known for. The production of manuscripts and stone and ivory carvings reached a peak during the Middle Byzantine period, as a renewed interest in Classical art and ancient literature emerged.

This demonstrated the Empire’s continual and active involvement with its ancient past, which helped extend the movement’s control throughout the various phases. This era marked the reopening of universities and the promotion of literature and art, which led to a renewed interest in classical Greek knowledge and aesthetics, which helped reestablish Greek as the official language.

Thus, the Middle Byzantine period, which was also referred to as the Macedonian Renaissance, was seen as a period of heightened stability and fortune.

The Latin Occupation (1204 – 1261 A.D.)

The disruption that occurred between the last two phases of Byzantine art was the Latin Occupation, which went on to have a profound effect on the Empire through the major political fragmentation that was caused. Armies of the Fourth Crusade attacked Europe and overthrew the capital of Constantinople, in an effort to return the Eastern Empire to Western Christendom.

The barbaric attack of the Crusade army on the Christian city and its people was completely unprecedented, which led to a significant breakdown of the Byzantine Empire’s nobility and ruling classes. This resulted in historians going on to earmark the Latin Occupation as a major decisive moment in medieval history. Essentially, a permanent division between the Catholic and Orthodox churches was created, which led to a slow deterioration of the Byzantine Empire until its final demise by the Ottoman Empire.

Due to this, many notable and sacred artworks and objects created during the Middle Byzantine period were destroyed and lost, while others were transported elsewhere.

Some objects can still be seen on display in Venice today, but this remains a small collection. Unfortunately, important bronze statues were melted down and the iconic Library of Constantinople was completely destroyed, which effectively wiped out the majority of the history of the Middle Byzantine era.

However, this new occupation found itself in competition with exiled Byzantine states, who fought to gain control. In 1261, the Byzantine state at Nicaea was able to expel the Latins from Constantinople, which led to the restoration of Byzantine power. Despite this, the imperial city never regained its former magnificence and power. The name of the city was then changed to “Palaiologoi” to mark the beginning of a new reigning dynasty that could possibly recover the authority that had been lost.

Late Byzantine Art (circa 1261 – 1453 A.D.)

Following the Latin Occupation, the final period of Byzantine art emerged. Known as the Late Byzantine art era, this phase focused on the renovation and restoration of Orthodox churches that were destroyed. Under the rule of a Byzantine Greek family that rose to nobility, the Late Byzantine art period was renamed the Palaiologan era, which began the longest-ruling dynasty of the Byzantine Empire.

As the Occupation had completely annihilated the economy and left most of Constantinople in ruins, artists began to make use of more inexpensive materials, which led to the rising popularity of miniature mosaic icons. As icon paintings further developed, the suffering experienced by the population resulted in a greater emphasis being placed on images of compassion. Paintings depicting the sufferings of Christ became commonplace during Late Byzantine art, as they invoked feelings of sympathy and tenderness.

Byzantine art and architecture managed to flourish for a significant period of time during the Palaiologan era, which was surprising due to the military and political circumstances faced by Byzantine rulers. The political borders of the Late Byzantine period were dramatically reduced due to the Latin Occupation; however, the religious influence of Byzantine art was still able to extend far beyond its own borders. The Late Byzantine era existed as a period of diminished wealth and stability, which led to its eventual demise by the Ottoman Empire.

This brought about the end of the Byzantine Empire, despite Byzantine art techniques living on in outposts like Greece, Italy, and even the Ottoman Empire. The development of Byzantine art was continued by the Russian Empire, which emerged around the time that Constantinople fell. This was seen as the heir of Byzantium, as the churches and icons were created in a distinctly Late Byzantine art manner.

The Renaissance was also said to borrow from the traditions of Byzantine art, which demonstrated the influence of this final period.

Byzantine Iconoclasm

At the start of the 8th century, the Byzantine Empire was constantly under duress and often at war with others. It was during this uneasy environment that dispute over the spiritual validity of icons began to erupt. In 730 A.D., Emperor Leo III formally banned all religious images and initiated a movement dubbed “Iconoclasm”, which saw the destruction of all religious icons. Society was also prompted by the belief that recent events, like military defeats and the 726 A.D. volcanic eruption in the Aegean Sea, were God’s retribution to humanity.

This dispute was further triggered by discussions between the imperial state and the church, as the disconnect between the holy and human nature of Christ was brought to the forefront. Those participating in the movement, known as Iconoclasts, believed that no icon could accurately represent both Christ’s divine and human nature.

Only portraying one aspect of Christ was considered to be blasphemous, which eventually led to society stopping producing images of Christ entirely as none were good enough.

While Iconoclasm significantly restricted the role of religious art and led to the damage of some portable icons and the removal of earlier pieces of mosaics, it never implanted a complete ban on the creation of figural art. Plenty of literary sources indicated that secular art continued to be produced during this period of the Byzantine era, with some structures that were built still existing today.

The Hagia Eirene in Constantinople is one of the best-kept examples of Iconoclastic church adornment today. The church was rebuilt after an earthquake in 740 A.D. and the interior was decorated with mosaics despite the stance on religious imagery at the time. Some churches that were built outside of the empire during this time were also seen to be decorated in a definite “Byzantine” style. This went on to demonstrate the continued efforts of artists who attempted to keep some characteristics of Byzantine art alive.

The Iconoclastic period lasted until about 843 A.D. and was a relatively uninterrupted period of time. After the death of Emperor Leo III, Empress Theodora took over. As she was intensely devoted to the adoration of icons, she formed a council that restored icon worship. Despite its destruction, the Iconoclastic Controversy was said to have had a prominent effect on the later development of art.

This renewed praise of icons formulated a coded system of symbols and iconographic types that were also used in future mosaics and paintings.

Characteristics of Byzantine Art

Byzantine Empire Art, also known as Constantinople art, existed as a very distinct period of artistic production. Artworks that were made had many similar characteristics that often overlapped at certain points. The elements present in Byzantine art pieces were all thought to be conventionally “Byzantine” in nature, which helped in the development of specific characteristics to identify these types of works.

Religious Iconography

Due to its complex history with the inclusion of icons, Byzantine art depicted various religious subjects almost entirely. These subjects were typically in the form of Jesus or the Virgin Mary, with different scenes from the Bible being incorporated as well. During this time, the church was very influential within Byzantine society due to its power and wealth and easily dictated the subject matters that were used.

Therefore, subjects of a religious nature were encouraged over others, which led to religion being the predominant theme.

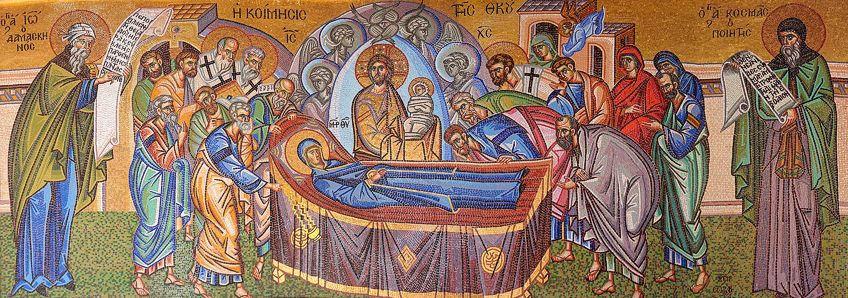

Some incredibly famous works from this period that showcase the integration of religious iconography remain to this day. A notable example of this is the Hagia Sophia, as iconography can be seen through its iconic mosaic work that still exists. Within the mosaic, Christ is depicted as the Pantocrator or ruler of the universe, effectively demonstrating the inclusion of religious icons in Byzantine artworks.

Mosaics

Another popular medium that was used within a significant amount of Byzantine artwork that was created was mosaics. The art of mosaic work quickly became one of the primary characteristics that were used to identified Byzantine art, as these artworks typically depicted religious scenes from the Bible and various spiritual icons. Artists who made use of this style made intricate mosaics out of thousands of glass, ceramic, and stone pieces that they arranged to form the images they desired.

Like the Romans who also made use of mosaics, Byzantine artists extended this art form by integrating more luxurious materials into their designs, such as precious stones and gold leaf. Mosaics within Byzantine Empire art were to create symbolic images of the divine and the Absolute and to evoke feelings associated with the heavenly realm. Most Byzantine mosaic works appeared to project celestial figures that seemed to be floating, which was further enhanced by the gold backgrounds that were used to represent the absence of earthly space.

The figures in Byzantine mosaics seemed to be isolated, as they were suspended in the air by their backgrounds. By placing these figures in a spiritual world, artists were able to give parishioners some access to this world through the mosaics that were created. Byzantine art intended to differ from Roman art through the types of mosaics that were produced, as artists placed focus on creating visions of the spiritual and the intangible world of Heaven.

Stylized Imagery

One of the simpler characteristics of Byzantine art was that artists tended to prefer stylized imagery over naturalistic depictions in the artworks that were made. This was because art aimed to encourage a sense of wonder and admiration for the church, which was further seen in the religious imagery that was chosen as a subject matter.

Thus, the use of elegant, floating figures and golden mosaic works highlighted the spirituality of religious subjects and essentially demonstrated their suitability in church settings.

Carved Ivory

Sculptures within the Byzantine era different greatly from Roman and Greek traditions, as the older characteristics were abandoned in favor of new ones. Byzantine artists pioneered relief sculptures, which were usually presented in the form of small moveable, and ordinary objects. These art pieces were also traditionally carved in ivory, as sculptures made from this material were known for their elegance and delicate detail.

Byzantine sculpture pieces made from ivory were thought to be highly valued in the West. Due to this, the artworks exerted a strong influence over the other artists and emerging mediums. These carved ivory pieces went on to inform many other movements, particularly the use of depth and space that was displayed in the Italian Renaissance.

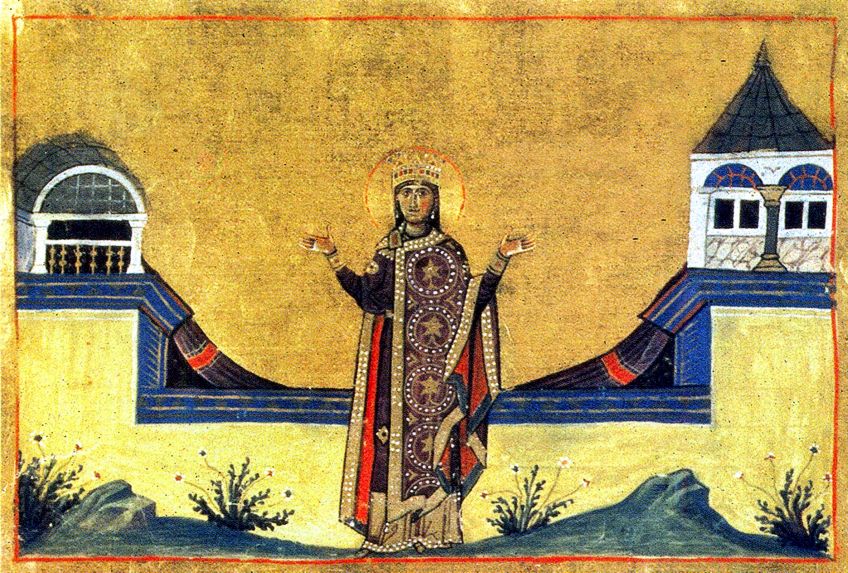

Illuminated Manuscripts

Another major genre of Byzantine art was the use of illuminated manuscripts, which referred to manuscripts that were accompanied by decoration in the form of miniature illustrations, initials, and marks in the borders. The elements of this medium, which were mostly used when illustrating texts of a religious, devotional, or theological nature, were seen as typical characteristics of Byzantine art.

Traditionally, a manuscript was only considered to be illuminated if the text was decorated in either gold or silver. Despite manuscript illumination not reaching the same impressive effects as the monumental paintings and mosaics that adorned churches, it was seen as an important characteristic that helped spread the Byzantine style and use of iconography throughout Europe.

Types of Byzantine Art

Throughout the Byzantine period, many mediums of art were experimented with. Unfortunately, due to the numerous conquests and occupations that happened during this time of history, much of the art created in the Byzantine Empire no longer exists. Out of these mediums, painting, sculpture, and architecture proved to be the most popular among artists and craftsmen.

Byzantine Painting

Paintings and frescoes created during the Byzantine era were typically seen on the inside of churches or cathedrals as decoration pieces. During this time, the Constantinople art pieces that were produced had three main purposes: to beautify buildings, to instruct the uneducated on matters essential for the benefit of their soul, and to support the faithful that they were indeed on the right road to salvation. In addition to paintings, churches were also adorned with beautiful mosaics that conveyed the same messages.

The subjects depicted in Byzantine painting frescos were limited, as they only included key religious figures like Jesus Christ and central events from the Bible.

In the large Christian basilica buildings where these paintings were traditionally found, depictions of Christ usually occupied the central dome to denote his importance. Other notable areas included the barrel of the dome which portrayed prophets, the joins between the vault and dome which depicted the evangelists, and the sanctuary which was home to the Virgin Mary and child.

The walls below the dome were also seen as significant, as they generally contained scenes from the New Testament about the lives of saints. The structure of these basilica’s also added to the importance given to the Byzantine paintings seen. The high ceilings and long side walls provided an ideal medium upon which to represent religious scenes and send visual messages to the congregation, as even the most modest of shrines were adorned with a plethora of fresco paintings.

Aside from these religious buildings, small wooden panels were also used as a popular canvas for paintings, however, this was generally seen in the late Byzantine art period. Paintings during this era varied greatly as they depended on the time frame or location. More attention to detail was paid to the subjects and their personality from the 13th century on, with some examples of this being seen in the Hagia Sophia in Trabzon. Daring color blends were also experimented with, as seen in the wall paintings in various Byzantine churches in Greece today.

Byzantine Sculpture

Throughout the entire Byzantine era, little sculpture was produced in comparison to the other art forms that were generated. However, the sculptures that were made were typically small relief carvings that were made out of ivory. Despite their diminutive size, these sculptures were sophisticated and elegant in construction and were used to decorate book covers, reliquary boxes, or other similar objects. In addition to ivory, marble and limestone existed as other common materials for sculptors to use for their craft.

Borrowing from late Roman art, where portrait sculptures were made to be incredibly realistic, Byzantian sculpture pieces continued the production of this trend.

At times, certain sculptures were also carved out of bronze and marble when they were said to represent emperors and popular charioteers. These types of sculptures were only carved in these unique materials due to the heightened status of their subject matter and were seen in the Hippodrome of Constantinople.

The majority of the limited figure sculptures created during the Byzantine art era were made of ivory. However, by the 6thcentury, three-dimensional portraits were considered to be quite rare as sculpture had not reached the popularity it once had in antiquity. Sadly, only a sole free-standing example of this sculpture work survives today. This sculpture, titled The Virgin and Child, was speculated to have been created between 1220 and 1230 A.D. and is on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in the United Kingdom today.

Byzantine Art and Architecture

The earliest reference to architecture in the Byzantine era was determined by the longitudinal Basilica church plans that were developed in Italy. This saw a favoring of large vaults and domes in the Byzantine architecture structures that were created, which led to the creation of various architectural innovations to come from this time period. In addition to domed roofs, the squinch and pendentive were incorporated. The squinch formed a base for an octagonal or spherical dome, while the pendentive placed a circular dome over a square room.

One of the original influences in Byzantine architecture was the Greek cross. This emblem, which had four arms of an equal length, was used in the design of many Byzantine churches for its proportionality. As architecture developed, surrounding structures were added to traditional churches, such as side chapels or a secondary narthex.

The architectural design of churches during the Byzantine Empire was optimal for the type of paintings and frescos that were to be added inside. Traditionally, at the top of the central dome, the figure of Christ was depicted as he was said to be the ruler of the universe and thus needed to be placed at the very top.

Below him, angels, archangels, and saints were generally depicted around the base of the dome, while the Virgin Mary was portrayed on a higher level in a half-dome. The lowest realm was built so as to be reserved for the congregation, which allowed worshippers to gain some sort of access to the Heavenly world that was depicted inside the dome.

Thus, all architectural elements within Byzantine churches were meticulously thought out, as they each played an important role in the storytelling of Christ and were shown to be accessible to ordinary churchgoers.

Famous Byzantine Artwork

Throughout the Byzantine Empire, hardly any distinction was made between artists and craftspeople, as both produced and assembled exquisite objects that were used for specific purposes. Thus, the artists behind the works were not as important as the actual works themselves, as these pieces were believed to have great influence over Byzantine society at the time.

A lot of artists within Byzantine art who went on to create illuminated manuscripts were often priests and monks, demonstrating the fine line that existed between so-called artists and professional individuals in society. Prior to the 13thcentury, it was very uncommon for an artist to sign their work. Due to this, the artists of some of the limited surviving artworks cannot be pinpointed, which again demonstrates that the status associated with creating art was not as important during the Byzantine Empire as it is today.

Potential reasons to explain why artists hardly signed their works were because they originally lacked social status, or that the artworks were made by groups of artists as opposed to a single person. However, the most plausible reason for this was because the personalization of artworks was believed to take away from its original purpose, particularly in religious art.

Byzantine artists were traditionally supported by patrons including emperors, monasteries, and churches, who commissioned works, further proving that their name on the artwork was not as important as the purpose for which it was destined.

Unfortunately, as not much artwork survived this period of history, we will be taking a look at just a few notable remaining pieces from the Byzantine art era.

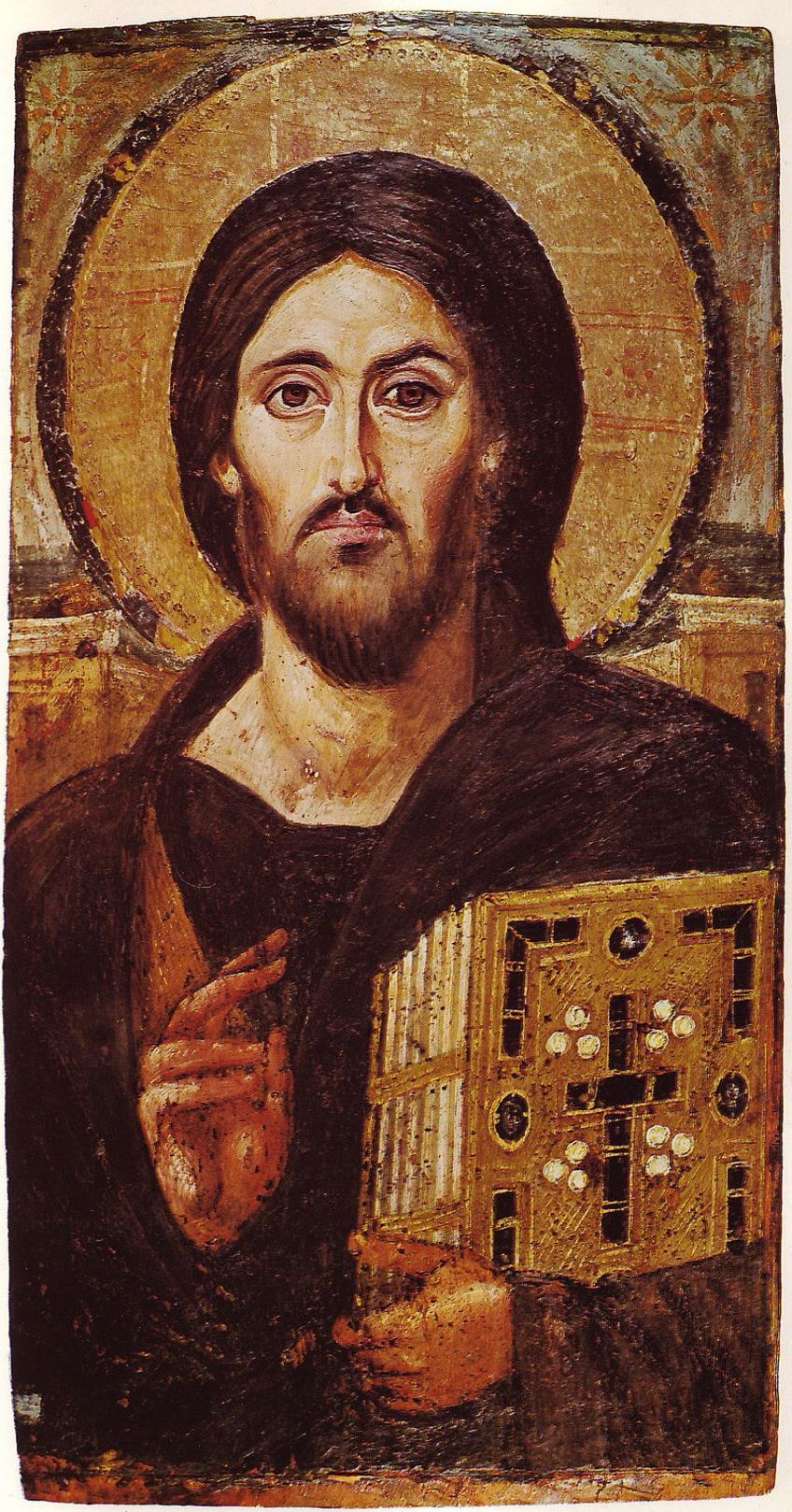

Christ Pantocrator (circa 6th century A.D.)

Existing as one of the oldest Byzantine religious icons of all time is the Christ Pantocrator of St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai, Egypt. Thought to be the earliest known version of the Pantocrator style that still survives today, this encaustic wood painting is one of the most significant and recognizable works in both the Byzantine art era and Eastern Orthodox Christianity.

Meaning “all-powerful”, this specific depiction of Christ Pantocrator set the precedent for the popular iconographic style that had begun to spread through the Byzantine Empire and eventually into Europe. It was painted in Constantinople sometime during the 6th century and sent to Emperor Justinian I as a gift to celebrate the establishment of the monastery near Mount Sinai. The location was also said to be associated with the prophet Moses and the Ten Commandments.

Due to its geographic isolation, this monastery in Egypt was a great distance away from Constantinople, which enabled it to evade the widespread devastation that happened to art because of the Iconoclastic Controversy. Because of this, it is often considered an exceptional example of Early Byzantine art as it makes up one of the few remaining pieces from that period of artistic production.

This style of painting was known as encaustic, which was a form of hot wax painting, whereby colored pigments were heated up and applied directly to surfaces such as prepared wood and canvases. With this artwork being painted on a wooden panel, Christ is depicted from a frontal angle with a distinct halo framing his head. Inside his halo, the subtle shadow of the cross is visible, demonstrating the spirituality of this work.

Further displays of religion are shown through the details in this painting. The right hand of Christ is raised in a gesture that was associated with blessing and he is holding a Gospel book adorned with jewels in the shape of a cross. With the figure appearing to be almost life-like as it fills up the majority of the pictorial frame, this painting compels viewers’ attention through the calm and direct gaze of Christ.

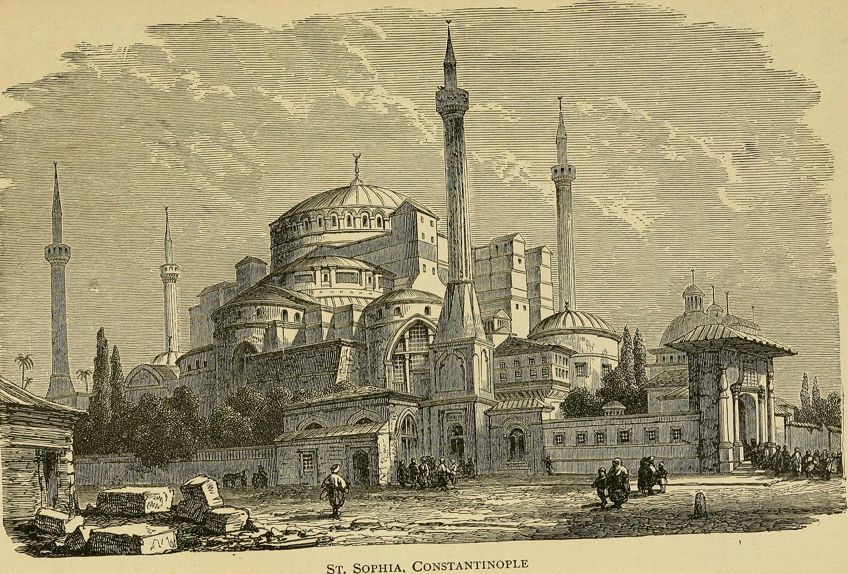

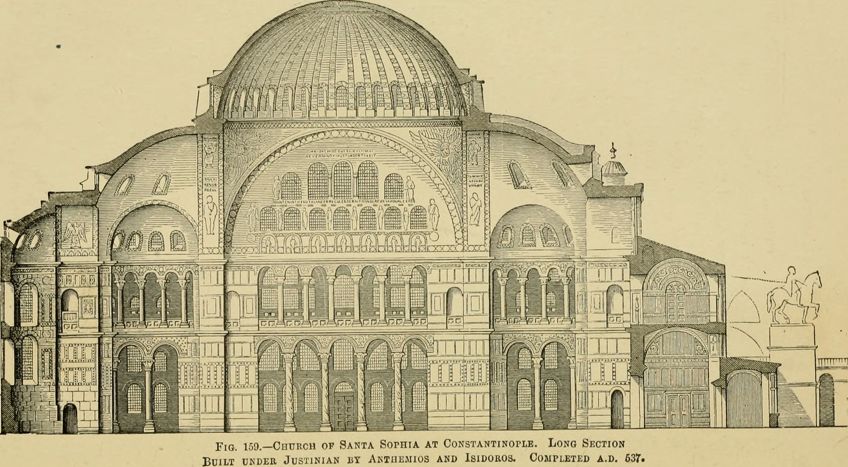

The Hagia Sophia (built in 537 A.D.)

One of the most iconic examples of the combination of Byzantine art and architecture is the Hagia Sophia, which was built during the Early Byzantine art period. Existing as the largest Christian church in the Byzantine Empire, the rebuilding of the Hagia Sophia was commissioned by Emperor Justinian during his extensive campaign in Constantinople.

Meaning “holy wisdom”, the Hagia Sophia is a mighty church characterized by its massive dome and light-filled interior, which can be visited in Istanbul, Turkey today.

Built as the patriarchal cathedral for the imperial city of Constantinople, the Hagia Sophia was a prominent and celebrated structure. The multiple windows, colored marble, dazzling mosaics, and golden highlights seen in its structure and decoration became the standard models for subsequent Byzantine architecture that developed during this period. The dome of the Hagia Sophia is the biggest in the world, which was executed by the architects’ pioneering the corners of the dome’s square base to evenly distribute its weight.

Existing as a symbol of the spiritual authority of the Orthodox church, the Hagia Sophia communicated social hierarchies through its interior structure. The ground floor and upper gallery were separated by gender and social class, with the higher section usually reserved for the Emperor and other noble patrons.

After the Turkish conquest of the Byzantine Empire, the Hagia Sophia was converted to a mosque, which it still is today. The interior decoration was slightly changed after its conversion, with mosaics being painted over in gold and subsequently replaced with medallions engraved with calligraphy. The building’s original design was maintained, as it was greatly admired by the Ottoman Empire, demonstrating the influence that iconic Byzantine architecture had, as the structure later became a model for Ottoman architecture.

Today, the Hagia Sophia stands as a national museum in addition to being a mosque. This was done so as to remove the structure from the many religious controversies that have still been associated with this site as time has gone on.

Despite the conflict associated with the Hagia Sophia, it still exists as one of the most significant examples of Byzantine art and architecture.

Emperor Justinian Mosaic (created between 546 – 556 A.D.)

This mosaic piece, which depicts Emperor Justinian I, is one of the most distinctive styles of mosaic works that was defined during the Early Byzantine art period. Existing as an iconic image of political authority from the Byzantine era, this mosaic of Emperor Justinian I can be viewed in the San Vitale church in Ravenna, Italy today.

Within this mosaic, the Emperor is portrayed to haloed and wearing a crown made out of jewels, while wearing royal purple robes and holding a big golden bowl for the bread of the Eucharist. Besides him, the Bishop Maximianus of Ravenna is depicted, along with three other members of the clergy. Other individuals include the imperial administration as well as a group of soldiers, who all make up the background of the mosaic.

By being placed in the center, the Emperor is seen as the primary authority between the power of the church and the influence of the government and military during the Byzantine Empire. The hierarchal style of the mosaic conveys a heavy atmosphere that simultaneously draws viewers in to be confronted by the direct gazes of the figures.

The similar stance adopted by each figure referenced the dimensions of time and earthly space, which appeared in the majority of mosaics in Early Byzantine art.

Legacy of the Byzantine Era

The Byzantine art era was an incredibly important period of historical and artistic development, as it went on to influence the development of early Western art history. The art movements that developed in its aftermath, while great in their own rights, were said to be merely attempted recreations of the type of art that was produced in the Byzantine era. This was simply because great splendor was incorporated into Byzantine Empire Art, which would not be seen for a while in emergent movements.

Some artworks from the Byzantine Empire were dispatched as diplomatic gestures to emperors while Constantinople still ruled, such as Byzantine silks and mosaic works. Artists were also sent to other regions to recreate the mosaics that were seen in the Byzantian churches at the time, which effectively demonstrated the great influence and draw that Byzantine art had on the different areas of the world.

While certain areas were seen as centers of Byzantine influence, like Venice and Norman Sicily, some artistic movements developed directly due to the Empire’s effect. A notable example of this is Islamic Art, which essentially began with artists and craftsmen who were mainly trained in Byzantine styles. While elements of Byzantine art were altered, it proved to be the underlying style that was referred to within the creation of Islamic Art and other various art movements as well.

Despite coming to a close in 1453 when the Empire was captured by the Ottoman Turks, Byzantine art proved to be very influential. The elements that made up Byzantine art had been widely diffused at this point, which enabled the movement to exist as a cultural heritage. Some aspects even survived the Turkish conquest and were used as new movements emerged, demonstrating the universal relevance of Byzantine art as a whole.

The Byzantine art period existed as an extremely fascinating movement, as it was seen as the starting point for other iconic art movements that emerged. Despite it occurring so many centuries ago, Byzantine art proved to be very influential, with some elements that are used in contemporary artworks today being traced back to this time in history. Spanning for over a millennium, the question “what is Byzantine art” is complex, as so much more can still be learned. If you have enjoyed reading this article, we encourage you to learn more.

Take a look at our Byzantine art webstory here!

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Byzantine Art – Traversing the Byzantine Empire Art Period.” Art in Context. June 17, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/byzantine-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 17 June). Byzantine Art – Traversing the Byzantine Empire Art Period. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/byzantine-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Byzantine Art – Traversing the Byzantine Empire Art Period.” Art in Context, June 17, 2021. https://artincontext.org/byzantine-art/.