Byzantine Architecture – Building Styles of Byzantium

Byzantine architecture is a construction style that thrived from 527 CE to 565 CE under the reign of Roman Emperor Justinian. An elevated dome, the outcome of the most advanced sixth-century technical methods, is its distinctive feature, in combination with significant use of interior mosaics. Throughout Justinian the Great’s rule, Byzantine church architecture was the dominant style of the eastern part of the Roman Empire, but the effects lasted centuries, and Byzantine architecture characteristics can still be observed in contemporary church designs.

Table of Contents

- 1 An Introduction to Byzantine Architecture

- 2 Ten Famous Byzantine Buildings

- 2.1 Hagia Irene, Istanbul (337 CE)

- 2.2 Basilica of Sant’apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna (505 CE)

- 2.3 Basilica Cistern, Istanbul (532 CE)

- 2.4 Hagia Sophia, Istanbul (537 CE)

- 2.5 Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna (547 CE)

- 2.6 Daphni Monastery, Chaidari (c. sixth century)

- 2.7 Hosios Loukas, Mount Helicon (c. 960 CE)

- 2.8 St. Mark’s Basilica, Venice (1094)

- 2.9 Byzantine Baths, Thessaloniki (c. 12th century)

- 2.10 Church of Saint Catherine, Thessaloniki (c. the 1300s)

- 3 Frequently Asked Questions

An Introduction to Byzantine Architecture

Most of what we now refer to as Constantinople Architecture or Byzantine architecture is religious, or congregation-related. Following the Edict of Milan in 313 CE, whereupon Emperor Constantine proclaimed his own Christianity, the Christian faith started to grow and Christians would not be frequently condemned anymore.

With freedom of religion, Christians could pray publicly and without fear of repercussions, and the fledgling faith grew quickly. As the requirement for houses of devotion grew, so did the demand for innovative solutions to architectural designs.

Byzantine Architecture Characteristics

- Byzantine buildings are square in design and have a central floor layout. They were modeled after the Greek cross in place of Gothic churches’ Latin crux. Early Byzantine buildings could feature large, prominent central Byzantine domes rising from a square foundation on semi-circular columns.

- Byzantine architecture combined Middle Eastern and Western architectural elements and practices. The Classical Order was abandoned in preference of pillars with ornamental impost slabs influenced by Middle Eastern patterns. Mosaic patterns and tales were often used. For instance, the mosaic depiction of Justinian at the Basilica of San Vitale honors the Emperor.

- The earlier Middle Ages were also a period of construction technique and material innovation. Clerestory windows became a prominent method for natural light and ventilation to penetrate a structure that would otherwise be gloomy and smoky.

- The most opulent rooms were adorned with thin slabs of stone or marble. Some of the pillars were built of marble as well. Brick and stones were also often utilized materials. Mosaics composed of glass or stone tesserae were frequently used in interior design. Byzantine interiors were furnished with expensive wooden furnishings such as beds, seats, benches, desks, bookcases, and gold or silver vessels with magnificent reliefs.

Byzantine Engineering and Construction Techniques

How can you fit a massive circular Byzantine dome into a square room? Byzantine engineers dabbled with many construction systems; when ceilings collapsed, they attempted something else. According to art historians, complex means for ensuring structural soundness, such as well-constructed deep underpinnings, timber tie-rod mechanisms in walls, vaults, foundations, and metallic chains inserted horizontally within brickwork, were devised.

To raise domes to greater levels, Byzantine designers moved to the mechanical usage of pendentives.

A dome may be raised from the tip of vertical cylinders, similar to a silo, using this approach, providing the dome height. The façade of the Church of San Vitale, similar to the Hagia Irene, is distinguished by a pendentive resembling a silo.

The inside of the Hagia Sophia, among the most iconic Byzantine constructions worldwide, is an excellent demonstration of pendentives seen from the inside.

Why is the Style Known as Constantinople Architecture and Byzantine Architecture?

Emperor Constantine transferred the Roman Empire’s capital from Rome to present-day Istanbul (then known as Byzantium) in the year 330 CE. Constantine dubbed Byzantium “Constantinople” in his honor. The Eastern Roman Empire is what we refer to as the Byzantine Empire. The Roman Empire was split into two parts: West and East.

Whereas the Eastern Roman Empire was concentrated in Byzantium, the Western Roman Empire was based in Ravenna, hence why Ravenna is a popular tourist attraction for Byzantine architecture. The Western Roman Empire disintegrated in Ravenna in 476 CE, but Justinian regained it in 540 CE. The Byzantine impact of Justinian may still be seen in Ravenna.

Western and Eastern Byzantine Architecture

In 482 CE, the Roman Emperor was born in Macedonia, not Rome. His birthplace is a crucial reason why the era of the Christian Emperor between 527 CE and 565 CE affected the character of architecture. Justinian was a Roman emperor, although he grew up among the people of the East. He was a Christian leader who brought two cultures together, which allowed for the exchange of building techniques and architectural elements.

Structures that had formerly resembled those in Rome began to take on more regional, Eastern characteristics.

Justinian reclaimed the Western Roman Empire from invaders, and architectural styles from the East were imported to the West. A mosaic depiction of Justinian from Ravenna’s Basilica of San Vitale attests to the Byzantine impact on the Ravenna region.

Today, Ravenna continues to be a major hub of Byzantine architecture.

Influences of Byzantine Buildings

Builders and architects learned from their undertakings as well as from one another. Byzantine church architecture established in the East inspired the construction and design of holy structures created in a variety of locations. The Church of the Saints Sergius and Bacchus, for example, was a little Istanbul attempt from the year 530 CE that affected the ultimate design of the most renowned Byzantine Church, the great Hagia Sophia.

In 1616, this prompted the development of the Blue Mosque. The Eastern Roman Empire had a significant impact on early Islamic architecture, especially Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock and the Umayyad Great Mosque of Damascus.

Eastern Byzantine architecture survived in Orthodox nations such as Romania and Russia, as can be observed in the Assumption Cathedral in Moscow from the 15th century.

In the Western Roman Empire, particularly Italian locations such as Ravenna, Byzantine architecture moved aside for Romanesque and Gothic architecture more swiftly, and the towering spires superseded the lofty domes of early religious design.

Architectural eras have no boundaries, notably throughout the Middle Ages.

Middle and Late Byzantine is a term used to describe the period of Medieval architecture from around 500 CE to 1500. In the end, names are less significant than impact, and architecture has always been vulnerable to the next big thing. Justinian’s rule had a legacy that lasted long after his demise in 565 CE.

Ten Famous Byzantine Buildings

Sadly, several of the most magnificent structures and monuments have been dismantled or have fallen into disrepair. The bulk of those who endured the collapse of the Byzantine Empire underwent significant adaptations and changes.

There are, however, a handful that serves as permanent memories of the Byzantine Empire’s previous magnificence and majesty, as well as its distinct architectural character.

Hagia Irene, Istanbul (337 CE)

| Structure Completed | 337 CE |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

| Function | Church |

| Architect | Constantine the Great (306 – 337 CE) |

The Hagia Irene is a Byzantine church in contemporary Istanbul, located in Topkapi Palace in the first courtyard. After Constantine’s Hagia Eirene was destroyed by fire, it was repaired by Justinian in the sixth century and considerably reconstructed by the emperor Constantine V in the eighth century, when its apse was ornamented with a modest mosaic cross.

After serving as an armory for decades throughout the Ottoman period, it became the Ottoman Empire’s first museum in the 19th century. Constantine is often credited with establishing the first church dedicated to Hagia Irene. Other accounts, however, say that Constantine restored or extended an existing church or small temple here.

Hagia Irene, often referred to as the “Old Church,” functioned as Constantinople’s cathedral until the opening of Hagia Sophia in 360 CE. After Paul the Confessor’s installation as bishop of Constantinople in Hagia Eirene approximately 337 CE, a series of confrontations erupted between Arian and Orthodox Christians, culminating in the deaths of 3,150 persons.

The mosaic artwork in the apse is undoubtedly Hagia Irene’s most notable characteristic, as it is a unique instance of Unorthodox art. Iconoclasm supporters, notably Constantine V, opposed the use of figural representation in sacred art, instead of replacing signs for persons.

Basilica of Sant’apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna (505 CE)

| Structure Completed | 505 CE |

| Location | Ravenna, Italy |

| Function | Basilica |

| Architect | Theodoric The Great (454 – 526 CE) |

Initially devoted to Salvatore and assigned to the Arian faith, the building was changed to Orthodoxy after the Byzantine Empire captured the city (mid-sixth century). As a result, it was devoted to the bishop of Tours, St. Martin, who was distinguished in the war against heresy. As per legend, the relics of St. Apollinaris, the saintly father of the church of Ravenna, were moved here from Classe in the eighth century.

The church was presumably titled after Apollinaris in this incarnation, but with the ending “Nuovo”. On the exterior, the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo appears to be fairly modest in design.

The brick tympanum façade is surrounded by two columns and a clerestory window and is topped by two tiny windows. It was originally surrounded by a four-sided porch, but it is now fronted by a modest and elegant 16th-century marble peristyle. The circular bell tower on the side, characteristic of Ravenna architecture, dates from the ninth to the eleventh centuries. The basilica’s interior features one of the planet’s most renowned mosaic sequences, including Early and Late Christianity.

This magnificent mosaic artwork stretches the length of the middle nave. It is an unrivaled masterwork in terms of artistic, pictorial representations, and philosophical worth. The basilica depicts the progression of Byzantine mosaics from Theodoric’s time to Justinian’s time.

Basilica Cistern, Istanbul (532 CE)

| Structure Completed | 532 CE |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

| Function | Cistern |

| Architect | Emperor Justinian (482 – 565 CE) |

This Byzantine architectural specimen is somewhat distinct from the lavish gold decoration found in Hagia Sophia. The Basilica Cistern is a big underground cistern in Istanbul. It was built during the era of Justinian I, as were many other Byzantine structures. The cistern served as a water treatment facility for the Great Palace and faced Hagia Sophia.

Though it was regularly filled with water when it was a cistern, it is currently usually kept empty to enable tourists access. The column bases depicting Medusa are a distinctive design component of the Basilica Cistern.

Some legends claim that Medusa’s head is turned sideways to prevent her from transforming men to stone, whereas others claim that it is just additional surface area required for an effective pillar. In any case, the utilitarian carving gives a touch of excitement to this Byzantine masterpiece.

According to ancient writings, the basilica had gardens encircled by a portico. As per historical sources, Emperor Constantine erected a building that was later repaired and expanded by Emperor Justinian following the Nika riots that ravaged the city in 532 AD.

Hagia Sophia, Istanbul (537 CE)

| Structure Completed | 537 CE |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

| Function | Mosque |

| Architect | Isidore of Miletus (442 – 537 CE) |

The Hagia Sophia, with its creative construction, deep culture, spiritual importance, and distinctive qualities, has been battling time for ages. It is the oldest cathedral, having been built on three occasions in the very same area.

With its stunning Byzantine domes that appear to float in the air, colossal marble pillars, and unmatched mosaic Byzantine patterns, it is one of the architectural wonders of the world. The sheer brilliant beauty of Byzantine architecture, with its exquisite interplay of dimension, lighting, and colors, inspires believers to worship.

The Hagia Sophia is on the “first hill” of Istanbul, at the point of the ancient peninsula, flanked on three sides by the Golden Horn, the Bosphorus, and the Sea of Marmara. The current Mosque is the third structure built in the same location, but with a distinct architectural philosophy than its preceding counterparts. Hagia Sophia was regarded as the epitome of Byzantine architecture and was thought to have changed the course of architectural history.

It was erected by Isidoros (engineer and geometrician) under the instruction of Emperor Justinian. The building began in 532 CE, was finished in five years, and was dedicated for service in 537 CE with considerable fanfare. The dome of the Hagia Sophia, along with hundreds of buildings, fell in 546 CE due to an earthquake.

Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna (547 CE)

| Structure Completed | 547 CE |

| Location | Ravenna, Italy |

| Function | Church |

| Architect | Julius Argentarius (c. 500 CE) |

The Basilica of San Vitale on Ravenna’s northeastern outskirts is an outstanding representative of Byzantine architecture. It was started while Ravenna was under Ostrogothic domination. It was built as a martyrium for the patron saint of Ravenna, St. Vitalis, and eventually became part of a Benedictine abbey somewhere before the mid-10th century, until it was disbanded in 1860.

Excluding the later vaults that supplanted the timber ceilings above the gallery, the majority of the original structure has been preserved.

The arches of the gallery and ambulatory were altered significantly, and outside buttresses were possibly constructed in the 12th century. Its southern stair turret was likewise converted into a campanile before collapsing in 1688.

The church underwent extensive renovation in the 16th century, and additional chapels were erected in the 18th century. Its mosaics were repaired in the mid-19th century. Excavations were carried out in the early 20th century, while the church was rebuilt in its believed original shape.

The bema and apse were elaborately adorned with marble and mosaic pavements, stucco ornamentation under the archways, colored windows, and gestural mosaics. The Proconnesian marble features, including columns and chancel decorations, were designed in accordance with the most recent Constantinopolitan styles.

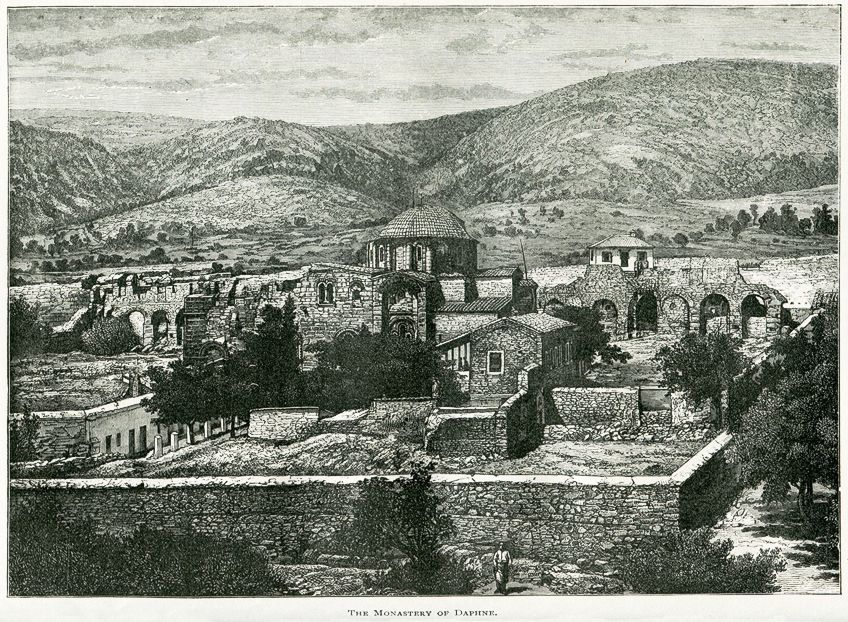

Daphni Monastery, Chaidari (c. sixth century)

| Structure Completed | c. sixth century |

| Location | Chaidari, Greece |

| Function | Monastery |

| Architect | Unknown (c. 6th century) |

The monastery is walled with an especially impressive defensive enclosure. This square enceinte contains turrets and fortifications on both sides, as well as two entrances on the eastern and western sides. The monastery extends back to Byzantine times, although the northern wall is the only remnant of the original square stronghold.

The four sides, each about 98 meters in length and a little more than a meter broad, are strengthened on the inside by enormous pillars bearing wide arches creating an arcade, a few of which still exist today.

A sheltered path ran around the castle walls atop the arches. The monastic church dominates the center of the castle, while the remains of the canteen are located immediately to the north. On the southern side of the church was a rectangular plaza with arcades, sets of apartments, and associated structures that, as discoveries have revealed, were renovated or reconstructed several times during the Monastery’s thousand-year history.

The monastery’s outstanding build quality, including cloisonné masonry, extravagant windows with Byzantine arched brick frames, and lavish interior ornamentation including superb mosaics on the wall surfaces, marble revetments on the bottom half of walls, and marble decorations of which only a few instances still remain. These connect the monastery’s development to elite organizations from the imperial court.

The mosaics that decorate the top walls represent Orthodox theology.

Hosios Loukas, Mount Helicon (c. 960 CE)

| Structure Completed | C. 960 CE |

| Location | Mount Helicon, Greece |

| Function | Monastery |

| Architect | Unknown (c. 920 CE) |

The earliest temple in the complex, Hosios Loukas, is the only one known with confidence to have been erected in the 10th century in its current location in mainland Greece. This centered parallelogram-shaped edifice is the nation’s earliest instance of the cross-in-square style; its design is based on Constantinople’s Lips Monastery.

The walls are “opus mixtum” (half stone, half brick, and marble) and have peculiar Byzantine patterns designs on them.

The Hosios Loukas is connected to a bigger cathedral church. The Katholikon is the oldest existing domed-octagon church, with eight piers set around the naos’s circumference. The hemispherical dome is supported by four squinches that connect the octagonal foundation beneath the dome to the square delineated by the walls underneath. The church’s primary cube is encircled on all 4 corners by chapels and galleries.

It is the biggest of three Middle Byzantine-era monasteries that still exist in Greece. It is distinguished from the Nea Moni and by its devotion to a solitary warrior saint.

The figure of Joshua on the outside wall of the Panagia church commemorates St. Luke’s prophecy regarding the reoccupation of Crete: Joshua was regarded as an ideal fighter of the truth, whose assistance was particularly useful in the wars conducted against the Arabs. The Katholikon has the best intact mosaic complex from the Macedonian Renaissance period.

St. Mark’s Basilica, Venice (1094)

| Structure Completed | 1094 |

| Location | Venice, Italy |

| Function | Basilica |

| Architect | Domenico I Contarini (c. 1050) |

The outside of the basilica’s western front is separated by three registers: lower, upper, and domes. Five round-arched entrances in the lowest register of the façade, surrounded by decorative marble pillars, lead into the entrance hall through Bronze doors. The upper level of murals in the lunettes of the side Byzantine arches depict episodes from Christ’s life (all Renaissance restorations), concluding in a 19th-century substitute Last Judgment lower down above the main doorway that superseded a broken one with the same theme.

Mosaics depicting the narrative of Saint Mark’s relics cover the lunettes of the lateral entrances, from right to left; the first one on the side is the only one on the façade that dates from the 13th century. The official subject is the Relics’ Confession.

The four bronze horses are displayed on the front. For the first time, we can obtain a clear understanding of the original mosaic arrangements through artworks and other portrayals. The stone sculptures are very restricted on the lower level, where the major focuses are a thicket of pillars and marble slabs with Byzantine patterns.

It has short bands of Romanesque workmanship on the doorways, finely carved margins of flora intermingled with figurines to the Byzantine arches and other components, and massive shallow relief saints between the vaults.

Along the roof, on the other hand, there is a line of sculptures, many of which are housed in their own little pavilions.

Byzantine Baths, Thessaloniki (c. 12th century)

| Structure Completed | c. 12th century |

| Location | Thessaloniki, Greece |

| Function | Baths |

| Architect | Unknown (c. 12th century) |

Public baths remained in use until the conclusion of Late Antiquity when they were phased out in preference of modest residential baths for the privileged. By the 11th century, there was a resurrection of bathhouse culture, with the development of local bathhouses, personal bathhouses for aristocrats, and even monastic baths.

This is the setting for Thessaloniki’s Byzantine bath. While it is presently the only remaining Byzantine bath in Thessaloniki, there were several others throughout the Byzantine era.

It was named the Kule Hamam throughout the Ottoman Empire (presumably after a nearby tower) and was close to a cemetery and mosque. It was considerably updated during centuries of use to meet the bathing practices of different ages as it continued to operate until 1940.

Despite its limited dimensions, the bath is plainly separated into three sections: a dressing room in a modest antechamber, a warm room, and a hot room. The hot chamber was used for the last stages of the bathing procedure, following which participants were rinsed in separate tubs.

From the antechamber to the heated room, there are two entrances. Its rooms interacted with one another as well as the hot room’s two huge chambers. One of the heated chambers is topped by a big dome. The hypocausts support the flooring of the warm room.

Church of Saint Catherine, Thessaloniki (c. the 1300s)

| Structure Completed | c. 1300s |

| Location | Thessaloniki, Greece |

| Function | Church |

| Architect | Unknown (c. the 1300s) |

The exquisite Palaiologan period church is one of the town’s most ‘obscure’ houses of worship: its Byzantine title is uncertain, and historical records are especially few in this case. The reality that existing Byzantine records confirm the establishment of over 50 Byzantine buildings and 40 monasteries, while some Byzantine writers correlate the number of churches in the town with the number of days in the year, gives a decent indication of the huge number of churches in Byzantine Thessaloniki.

Only 15 have endured to the current day, and only ten of these have their traditional names.

The endeavor to identify the Byzantine buildings hidden underneath contemporary monikers and the Turkish titles that predated them – for the vast bulk of them were transformed into mosques – is very often as engrossing as the storyline of a great detective narrative.

Documentation from Byzantine and Turkish sources must be merged with proof provided by the historic sites themselves and excavations performed on them. The church of Hagia Aikaterini was turned into a mosque during the time of Sultan Bayezid II by Yakup Pasa of Beylerbeyi, to whom it attributed its Turkish name.

And that concludes our article about Byzantine architecture. Otherwise known as Constantinople architecture, this style had its roots in the period of rule under Justinian and combined Middle Eastern and Western architectural elements and practices. The Classical Order was abandoned in preference of pillars with ornamental impost slabs influenced by Middle Eastern patterns.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Was It Known as Byzantine Architecture?

In the year 330 CE, Emperor Constantine transferred the Roman Empire’s capital from Rome to present-day Istanbul. At that time, the area was known as Byzantium. Hence the name Byzantine architecture.

What Are the Byzantine Architecture Characteristics?

The Byzantine domes of the roof were the most distinguishing feature. The squinch or the pendentive were both employed to allow a dome to sit atop a square base. Vast expanses and opulent embellishment characterized Byzantine buildings, such as marble pillars and inlays, mosaics on arches, inlaid-stone sidewalks, and occasionally gilded ornate ceilings.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Byzantine Architecture – Building Styles of Byzantium.” Art in Context. March 1, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/byzantine-architecture/

van Huyssteen, J. (2022, 1 March). Byzantine Architecture – Building Styles of Byzantium. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/byzantine-architecture/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Byzantine Architecture – Building Styles of Byzantium.” Art in Context, March 1, 2022. https://artincontext.org/byzantine-architecture/.