Precisionism – Capturing the Dynamism of the Modern World in Art

As the first indigenous style of modern art in the United States, Precisionism attempted to accurately capture the dynamism of modern technology. While it featured distinctly American subject matter, this artistic style combined the various formal features of European Modern art, thus contributing to the rise of American Modernism.

Table of Contents

Pinpointing Precisionism in Art

Emerging during what is often called the Machine Age, there was initially no clear label for this loosely defined style of art, nor is there a consensus on how the term came to be used. Generally, the official description “Precisionists” was applied to a style adopted by American painters and photographers from the 1910s until the 1940s, coinciding with the advent of the Great Depression.

What Is Precisionism?

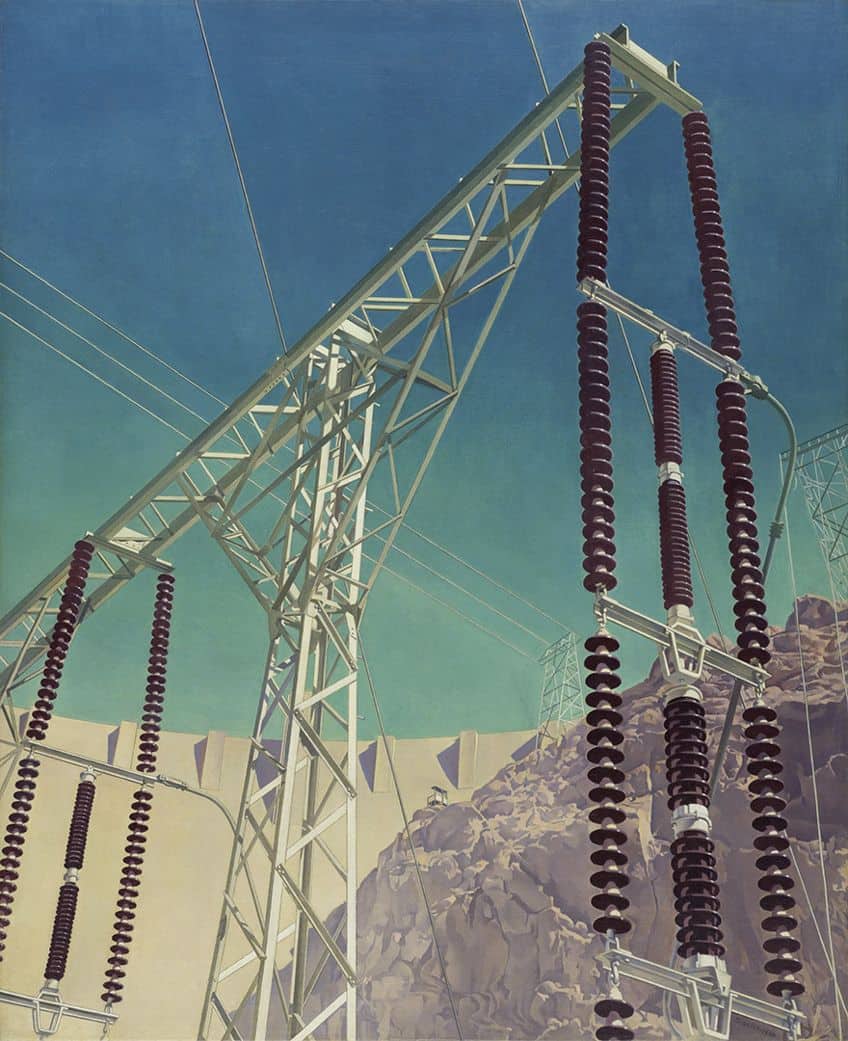

As the name suggests, Precisionism emphasized linear precision or the use of precise lines in art. Precisionism sought to refine art through simplicity, and clarity. It was characterized by rigidly unambiguous, yet fragmented geometric forms that intentionally mimicked products produced in the assembly line or through other technological processes. Precisionism paintings featured subjects of the early twentieth-century modern American landscape such as engineering advances, or agricultural structures. These could include steel mills, coal mines, factories, skyscrapers, and bridges. By depicting urban settings and industrial locales Precisionists highlighted the unique character of American architecture.

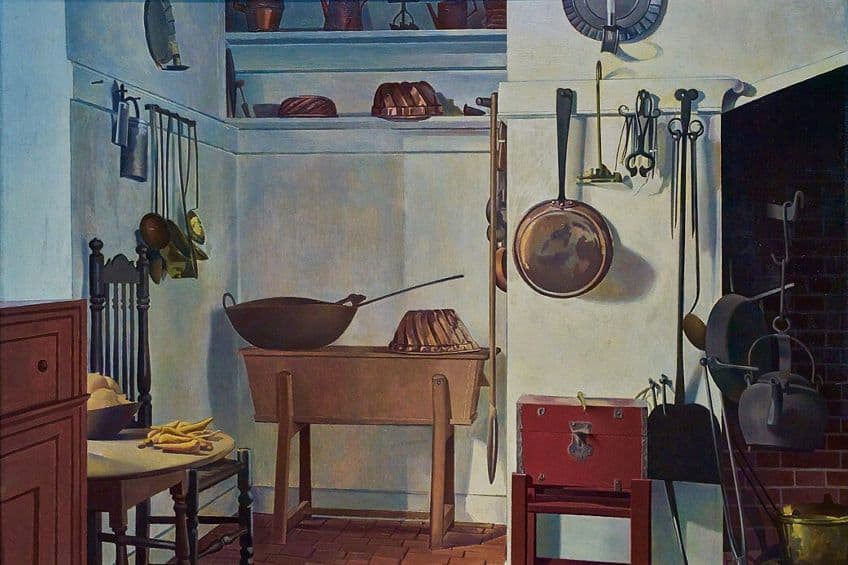

Occasionally, the Precisionist style was applied to traditional motifs such as still life painting.

While Precisionism was about celebrating the utopian ideal of modern industrial technology, it was also about highlighting the underlying reality of the dehumanizing and destructive effects of technological progress. Often, this style used the imposing scale, or chaos of architectural form or urban spaces to hint at these underlying realities. Because of its interest in technology, Precisionism art is characterized by its exact angles, unexpected viewpoints, and dynamic compositions. It was heavily influenced by the sharp focus and cropping techniques of 20th century American photography. The style took so many cues from photography that it was sometimes referred to as Sharp Focus Realism.

The History of Precisionism Art

The style of Precisionism first emerged during the early years of the 20th century. After World War One, the United States economy boomed, causing innovations in technology, and improving industrial production and construction in urban settings. American culture was shifting and there was a renewed interest in regional landscapes, artifacts, traditions, identity, and history. By the 1920s, a group of American painters responded to this shift, by depicting expanding urban and industrial landscapes with a regional artistic style.

While the Precisionism artists distanced themselves from European traditions, they were heavily influenced by them.

They borrowed extensively from the Cubists who attempted to complicate form and the Futurists whose work venerated futuristic technological narratives. Because of these connections, Precisionists were also referred to as Cubist Realists, Modern Classicists, or Immaculates. There are many theories as to who the original source of the term was. The most likely founder of Precisionism was the foremost director of the Museum of Modern art in New York Alfred H Barr who officially used the term in 1927. Conflicting views suggest that it was the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis’ 1960 exhibition The Precisionist View in American Art that officially acknowledged this American art style.

Precisionism Artists

One of the key Precisionism artists Charles Sheeler is also suggested as the first to coin the term Precisionism. Other artists who applied this new, hard-edged style include Georgia O’Keeffe, Charles DeMuth, Joseph Stella, Paul Strand, and Peter Bloom. Many of these artists consistently made Precisionism art for many decades, while others swiftly moved on to other styles.

Precisionism art attracted the initial patronage of influential figures like the gallery owner, publisher, and photographer Alfred Stiglitz.

Stiglitz’s New York gallery became a central proponent of the success of Precisionism. After the initial group of Precisionists, a second generation of artists creating Precisionism paintings emerged during the 1930s. However, as the United States approached World War II, the style began to fade again.

Joseph Stella

| Birth and Death | 13 June 1877 – 5 November 1946 |

| Place of Birth | New York City, New York, United States |

| Associated Art Movements | Precisionism, Futurism, Modern art, and American Modernism |

| Nationality | Italian American |

Joseph Stella was a Futurist painter who contributed greatly to the Precisionist tradition of painting in industrial America. Most of Stella’s artworks can be classed as abstract, although their thick, dramatic gestures are often representations of urban features. Stella’s ever-changing artistic style allowed him to become incredibly influential on many kinds of artists including but not limited to color field painters. Constantly breaking away from the traditional styles he had been taught as a student of art, the artist eventually committed to Futurism, in his attempts to capture the complex context of the machine age. In 1923, the Italian-born Stella became an American citizen, and began searching for distinctly American applications of his newfound artistic style.

Between 1913 and 1918, Joseph Stella completed six paintings of Brooklyn’s Coney Island. Coney Island (1914) circular composition is reminiscent of Renaissance depictions of holy subjects. Though there are no obvious or discernible lamps, Coney Island is a kaleidoscope of dazzling colors. Stella’s multi-colored hard-edged forms and prismatic shafts represent the glow of thousands of electric light bulbs at a time when electricity was still quite new. The fragmented mosaic-like forms amount to a series of spell-binding signs meant to represent the technological triumphs of amusement park and boardwalk architecture. Celebrating the resort’s popular attractions and sideshows such as Steeplechase Park and Luna Park, Coney Island epitomizes the intoxicating excitement and disorienting commotion of modern life.

By the 1920s, the city’s urban landscape became the subject of some of the artist’s most well-known artworks. Stella blended elements of the architectural, geometric forms of lower Manhattan with motifs from Cubism and Futurism.

In 1896, soon after arriving in America and seeing it for the first time, Stella’s preoccupation with the Brooklyn Bridge began. He saw the structure as a shrine of American civilization. But it was only when he moved to Brooklyn that he started transposing his fascination onto canvas. He would return to the theme of the Brooklyn Bridge throughout his career. Although Stella’s depictions of the Brooklyn Bridge seem to be rigidly precise, some irregularities create interest. In Old Brooklyn Bridge (1941), the bridge’s exaggerated sweep of steel seems cemented in an overriding sense of precise and symmetrical composition. The dynamic angles created by these harmonious precisionist lines make the bridge resemble some large mechanical structure. Stella’s paintings of the Brooklyn Bridge made him one of America’s most revered modernist painters.

Charles DeMuth

| Birth and Death | 8 November 1883 – 23 October 1935 |

| Place of Birth | Lancaster, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Associated Art Movements | Precisionism |

| Nationality | American |

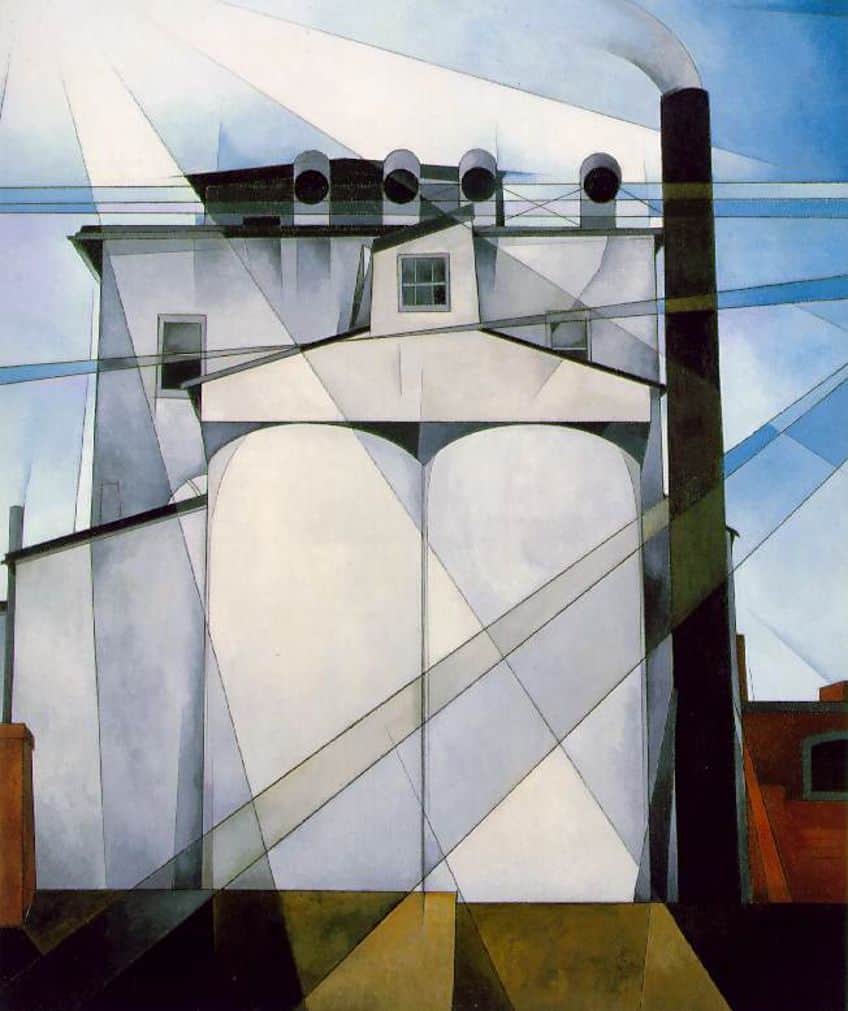

American artist Charles Demuth initially worked in watercolors before later turning to oils. He specifically used oil tempera and began working in a precisionist style creating a balance between abstraction and realism. Demuth seldom spoke about his paintings or any meaning that might be attributed to them. He wanted his viewer to have their own unencumbered interpretation of his work. While he focused on a regional aesthetic of scenes and structures from his hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Demuth had a diverse artistic approach. Between 1924 and 1929 Demuth painted eight symbolic images which functioned as tributes to modern American culture. These images, which do not subscribe to their subjects’ conventional likeness, are among the best-known precisionism paintings.

In Welcome To Our City (1921) Demuth painted interlocking red planes in the foreground which evoke the brick pattern of modern industrial buildings. The series of alternating, arched, radiant, and diagonal planes is painted in subtle gradients. In the background is a looming, seemingly tilted courthouse dome, hinting at Lancaster’s history. The blue in the top right-hand corner and the flat black sections suggest sky, creating the illusion of a conventional landscape. A single blank window echoes the Dome curved, which towers above utilitarian walls and roofs occasioned by chimneys. Though partly concealed, the letters I TH, and S can be seen in the upper left corner. The stark style of commercial graphics is achieved through simplified forms and interlocking, flattened planes. The lines are sharp and crisp, a fundamental principle of the Precisionism style.

Water Tower (1931) is another prime example of Precisionism art, and it just might be DeMuth’s most famous image.

During the 1930s its subject, the Armstrong Cork Company was America’s leading linoleum producer. Instead of portraying the sprawling factory, Demuth zoned in on the water tower soaring above the plant. By using the contrasting colors of deep red and steel gray, Demuth turned the frigid, mundane structures into monumental forms. DeMuth’s My Egypt (1927) is part of a series of seven-panel paintings featuring factory buildings in Lancaster. The focal point of this painting is a concrete and steel grain elevator owned by John W. Eshelman & Sons. The sequence of intersecting diagonal planes produces geometric vibrancy in the image. My Egypt’s low vantage point causing the grain elevator assumes a monumentality emphasized by the rest of the elements. At the very bottom of the image, brown rectangular shapes suggest lower rooftops in the more traditional architecture of the neighboring buildings on smaller family farms.

This painting’s execution and title may allude to the correlations between industry and religion. Considering the slave labor involved in the building of the pyramids, Demuth draws parallels with the dehumanizing conditions of the working class in Industrial America. At the same time, the artist seems to make the implication that industry is a triumphant symbol of American achievement with the factory operating as a modern-day equivalent to the iconic structures of ancient Egypt.

Charles Sheeler

| Birth and Death | 16 July 1883 – 7 May 1965 |

| Place of Birth | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Associated Art Movements | Precisionism and American Modernism |

| Nationality | American |

Charles Sheeler is an abstract realist painter and photographer who contributed notably to the development of American modernism. He is recognized for his dynamic paintings of New York City and his commitment to the artistic principles of Precisionism. Being a self-proclaimed Precisionist, Sheeler used his photographic works as foundations for his paintings. In this way, the artist merged the sharp detail of the photographic medium with a taut abstracted aesthetic.

To transform his photographs into abstract designs on canvas, Sheeler employed quite a structured painterly style. This method helped the artist capture the streamlined grandeur of his ready-made subject – New York City. The sheer magnitude of design and technology behind utilitarian buildings such as skyscrapers or factory complexes impressed Sheeler greatly. He recognized an innate Americanness in these urban locations and viewed the geometry of these buildings as an ideal starting point for his precisionist aesthetic.

Sheeler’s precisionism art often featured sharply defined, solid, angular planes of color.

Most of his compositions were epitomized by intense direct light which drew the viewer’s eye towards the various diagonal intersections of light and shadow, creating strong focal points in these hard-edged, geometric images. As is expected of Precisionism artists, American buildings, like factories, had become the modern equivalent of a cathedral. Seeing them as something of a substitute for religious experience. Even though these are such social structures, Sheeler’s images are often devoid of people. This could be an acknowledgment of the dichotomy between America’s explosive industrial progress and events such as the Great Depression which had devastated rural America at around the same time.

By the late 1940s, Sheeler’s artistic practice had undergone yet another substantial conversion, shifting from photographic realism towards more abstract compositions. His use of photography as a basis for his paintings involved a precise process of elimination. Sheeler either simplified or eliminated much of the detail in the photographic references. He then added imaginary shapes to add interest and dynamism.

Oscillating between realism and abstraction, this painting was not shy about its European influences. Sheeler looked up to pioneers of European abstraction like Pablo Picasso. Nonetheless, he strove for his work to appear not European but distinctly American. To this end, Sheeler produced a series of paintings featuring the factory complex. Of this series, it was the classic landscape Stacks in Celebration (1954), which became a phenomenal success and one of the most well-known and widely exhibited of its era.

Sheeler’s Stacks in Celebration depicts different sections of the factory where cement was made, stored, and shipped for sale. The artist’s admiration of the straightforward architecture is palpable in this image. Through a dynamic arrangement of elements, the image emphasizes the structure’s plan which is determined by function rather than architectural conventions. In this image, Sheeler used the factory as an icon of American existence.

Juxtaposing this reality with his invented abstract colors and patterns, Sheeler directs the viewer to the parallels between Stacks in Celebration and the factory – both products of innovation and the human touch.

Georgia O’Keeffe

| Birth and Death | 15 November 1887 – 6 March 1986 |

| Place of Birth | Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, United States |

| Associated Art Movements | Precisionism and American Modernism |

| Nationality | American |

Most art lovers will know Georgia O’Keeffe for her large flower paintings or her New Mexico landscapes. Although O’Keeffe sternly denied that any of her paintings contained sexual innuendo, her style of painting is signified by succulent shapes and radiant colors that many viewers could not help but interpret as somehow sensual.

O’Keeffe intended to challenge the viewer’s perceptive habits. She used scale to enable her viewer to observe minute details in her subjects that might otherwise have been overlooked, focusing on small ordinary flowers in her suggestion of the overwhelming immensity of nature. These images were so successful, they have become prevalent in popular culture, spurred forward by the rise of feminism.

Somewhat less popular than her sensual flowers are O’Keeffe’s architectural Precisionism paintings from her years in New York. This substantial portion of her body of work marked an influential contribution to the Precisionism style. In these works, O’Keeffe painted imposing cityscapes featuring New York skyscrapers and other architectural forms. One of O’Keeffe’s most iconic paintings in this series is Radiator Building—Night, New York (1927). This artwork is a haunting depiction of an art deco skyscraper on West 40th Street in midtown Manhattan, New York. The magnificent radiator building had just been completed three years before the completion of this painting. O’Keeffe places its subject – the radiator building at the center of the composition.

For comparison, the artist adds a shorter building next to it. This heightens the radiator building giving it a domineering and dramatic presence over other elements in the image. But there is also a delicacy to this image. Smoke and steam can be seen rising upwards from a ventilation system of some sort to the right of the radiator building. O’Keeffe’s painterly handling of the smoke reminds us of her iconic flowers.

Furthermore, the painting places the viewer at a low viewpoint, making them feel like they would need to crane their necks skyward if they viewed the building in person.

The low-angle composition is supplemented by the tightly focused view. This cropped perspective is reminiscent of photographic compositional techniques. O’Keeffe’s depiction of Manhattan’s radiator building is set on a backdrop of a night with an overcast sky, appearing to tower above the moon. The radiator building shimmers with light from the inside out through tiny windows peppering the somber façade. Floodlights are scanning the night sky and a glowing red neon sign on the left-hand side, in the background further emphasizes the building’s height. This interplay between darkness and light highlights the geometric lines of the architectural structure.

Through her use of simplified forms, O’Keeffe abbreviated her skyscraper down to simple geometric forms. Radiator Building – Night, New York stands as a triumphant symbol of the then brand-new building. It captures the mangled magnificence of skyscrapers in general. They are symbols of modern America in the 1920s, used by Precisionism artists to speak to both the successes and failures of American capitalism. O’Keeffe’s own disillusionment with city life provided fertile ground for her portrayals of skyscrapers and their role in America.

The 1929 Stock Market Crash was a key turning point in the development of Precisionism. By the 1940s, after the Second World War, a widespread disillusionment around the destructive power of technology had manifested. At the same time, European artists began moving to the United States, attempting to escape Nazi rule. They brought avant-garde approaches that challenged the realist portrayals that characterized styles like Precisionism. This new wave of artists strived for artistic styles that were rooted in feelings instead of form and gravitated towards abstraction, disrupting Precisionism’s confidence in precision and technological progress. With all the suffering going on in the world, painting giant skyscrapers seemed gratuitous and in poor taste. Over time, Precisionism’s key promoters either passed away or moved on artistically, causing the American style to fade.

Frequently Asked Questions

Was Precisionism Political?

Like any art movement or style, Precisionism was developed because of the wider social context. Being a specifically American style at a time when the country was experiencing such political and economic turmoil, its birth had undeniable political implications.

What Is Precisionism’s Importance?

Even though the industrial landscape was a frequent subject in American art, Precisionism is often underrated. However, Precisionism was an important development because it influenced the development of American modernism. Precisionism is what led American artists away from the limitations of pure realism, into the possibilities of movements such as Abstract Expressionism and pure abstraction.

What Is the Precisionist Art Movement?

Some would argue that Precisionism never became a full-fledged movement. It was more of a conceptual and practical approach. The American artists associated with Precisionism were heavily influenced by European movements such as Cubism, Purism, and Futurism. Using precisely defined geometrical forms, Precisionism focused on themes of industrialization apparent in the modern American landscape.

Was Edward Hopper a Precisionist Artist?

The question of whether the famous American artist Edward Hopper was a Precisionist is debatable. Although his paintings were generally less sharp and crisp, they incorporated many of the approaches aligned with Precisionism.

Heidi Sincuba was the Head of Painting at Rhodes University from 2017 to 2020 and part of the first Artist Run Practice and Theory course at Konstfack in Stockholm, 2021. They completed their BFA at Artez Arnhem in the Netherlands, MFA at Goldsmiths University of London, and are currently a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Cape Town.

Heidi Sincuba’s own practice explores fugitivity through painting, drawing, text, textiles, performance, and installation. This praxis is founded on a conceptual intersection of biomythographic experimentation, existential automatism, and African ancestral knowledge systems. These methodologies of multiplicity result in a fluid and speculative aesthetic, continually manifesting and metamorphosing its material conditions.

Learn more about the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Thembeka Heidi, Sincuba, “Precisionism – Capturing the Dynamism of the Modern World in Art.” Art in Context. February 6, 2024. URL: https://artincontext.org/precisionism/

Sincuba, T. (2024, 6 February). Precisionism – Capturing the Dynamism of the Modern World in Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/precisionism/

Sincuba, Thembeka Heidi. “Precisionism – Capturing the Dynamism of the Modern World in Art.” Art in Context, February 6, 2024. https://artincontext.org/precisionism/.