Francisco de Goya – Father of Unflinching Spanish Realism

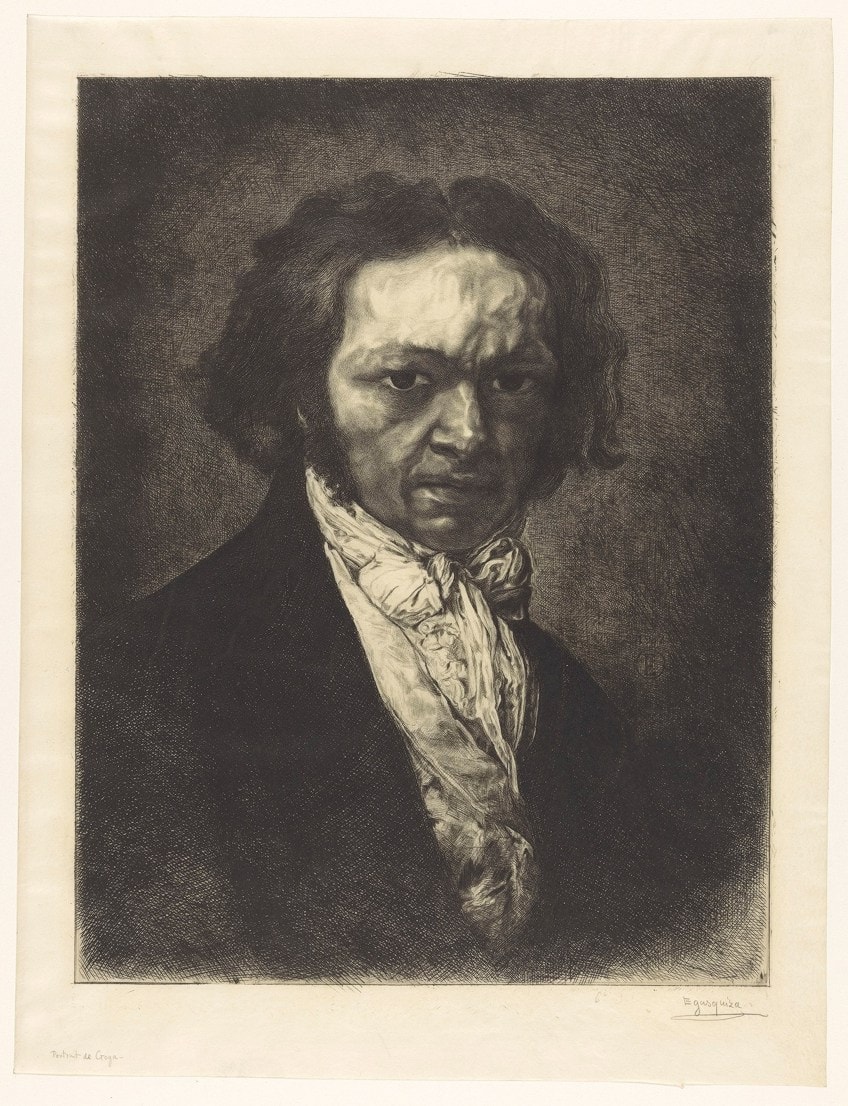

Francisco de Goya was a Romantic artist from Spain, regarded as a highly influential figure in the later years of the 18th century. Francisco Goya’s paintings, engravings, and drawings depicted the political and historical turmoil of the era, thereby influencing many artists that followed after him. Francisco Goya’s works represent the oeuvre of one of the very last Old Masters, and simultaneously the oeuvre of a pioneer of the moderns.

Table of Contents

Francisco de Goya’s Biography and Art

Spanish painter Goya’s art exhibits Romanticism’s focus on individualism, creativity, and feeling, which is particularly visible in his engravings and later personal works. Goya the artist was a keen analyzer of his surroundings, and his works responded immediately to the political upheavals of his time, from the Enlightenment’s liberation to the Inquisition’s suppression, to the atrocities of war after Napoleon’s invasion.

Francisco Goya’s works had a huge influence on succeeding contemporary painters, both for their originality and sociopolitical engagement.

The Early Life of Francisco de Goya

Francisco Goya was born on the 30th of March, 1746, in Aragón, Spain, to José de Goya and Gracia de Salvador. The family had relocated from Zaragoza that year, however, there is no indication as to why; most likely, José was assigned to serve there. They were from a lower-middle-class family. José was the child of a solicitor of Basque ancestry, with origins from Zerain. He worked as a gilder, specializing in spiritual and beautiful craftwork. During the restoration of Zaragoza’s main church, the Santa Maria del Pilar, he handled the gilding and many of the embellishments.

Even though no records were kept, it is believed that Goya studied at the Escuelas Pías de San Antón, which provided free education.

His schooling appears to have been competent but not illuminating; he possessed literacy and arithmetic skills, as well as some acquaintance with the classics. Goya the artist appears to have had little more interest in philosophical or spiritual topics than a carpenter, and his ideas on art were quite practical: Goya was no theorist.

Goya’s Italian Experience

At the age of 14, Goya began studying under the artist José Luzán, where he reproduced stamps for four years until deciding to create his own works, as he later stated, “create from my conception.” He relocated to Madrid to train under Anton Raphael Mengs, a well-known artist among the Spanish monarchy. He had disagreements with his instructor, and his exams were disappointing. Goya applied to the Real Academia of Bellas Artes de San Fernando twice, once in 1763 and another time three years later in 1766, but was declined admission.

Rome was Europe’s creative center at the time, and it had all of the prototypes of ancient antiquity, whereas Spain, despite its tremendous aesthetic triumphs in the past, was without a clear creative direction.

After failing to get a fellowship, Goya traveled to Rome at his own cost, following in the long history of European painters dating back at least to Albrecht Dürer. Because he was unrecognized at the time, documentation is scarce and ambiguous. According to early biographers, he traveled to Rome with a band of bullfighters, where he performed as a public performer, for a Russian envoy, or had fallen in love with an attractive youthful nun whom he intended to kidnap from her abbey.

During his stay, Goya may have painted two remaining mythological artworks, “Sacrifice to Pan” and “Sacrifice to Vesta”, which have both been dated to 1771.

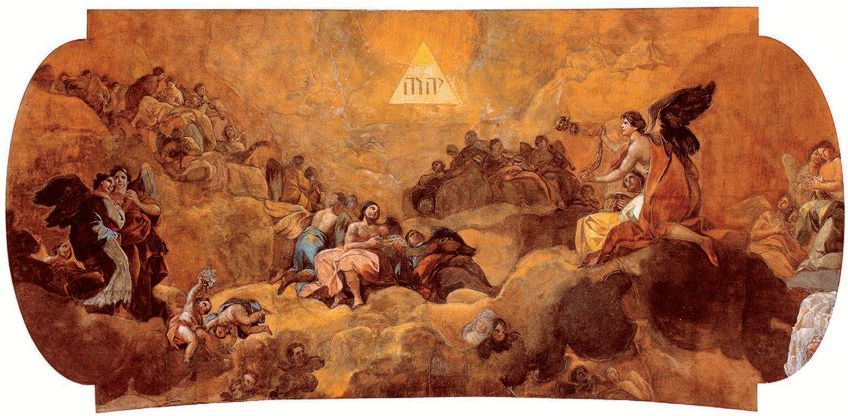

In 1771, he took second place in an art contest sponsored by the City of Parma. That same year, he journeyed to Zaragoza and produced Adoration of the Name of God, the paintings of the Sobradiel Palace, and a sequence of frescoes for the Charterhouse of Aula Dei’s monastery chapel. He trained with the painter Francisco Bayeu y Subas, and his work began to show traces of the exquisite tones that made him renowned. He met Francisco Bayeu and married Josefa, his sister.

Goya the Artist’s Madrid Years

In 1777 Goya was commissioned by the Royal Tapestry Factory to create a series of tapestry illustrations. Over the course of five years, he created 42 designs, most of which were employed to embellish and protect the stone walls of El Escorial, the Spanish monarchs’ home. While producing tapestries was neither distinguished nor well compensated, Goya’s illustrations are largely popular in a rococo manner, and he exploited them to introduce himself to the notice of a larger audience.

The cartoons were not his sole royal assignments; they were followed by a set of engravings, most of which were reproductions after great artists like Velázquez.

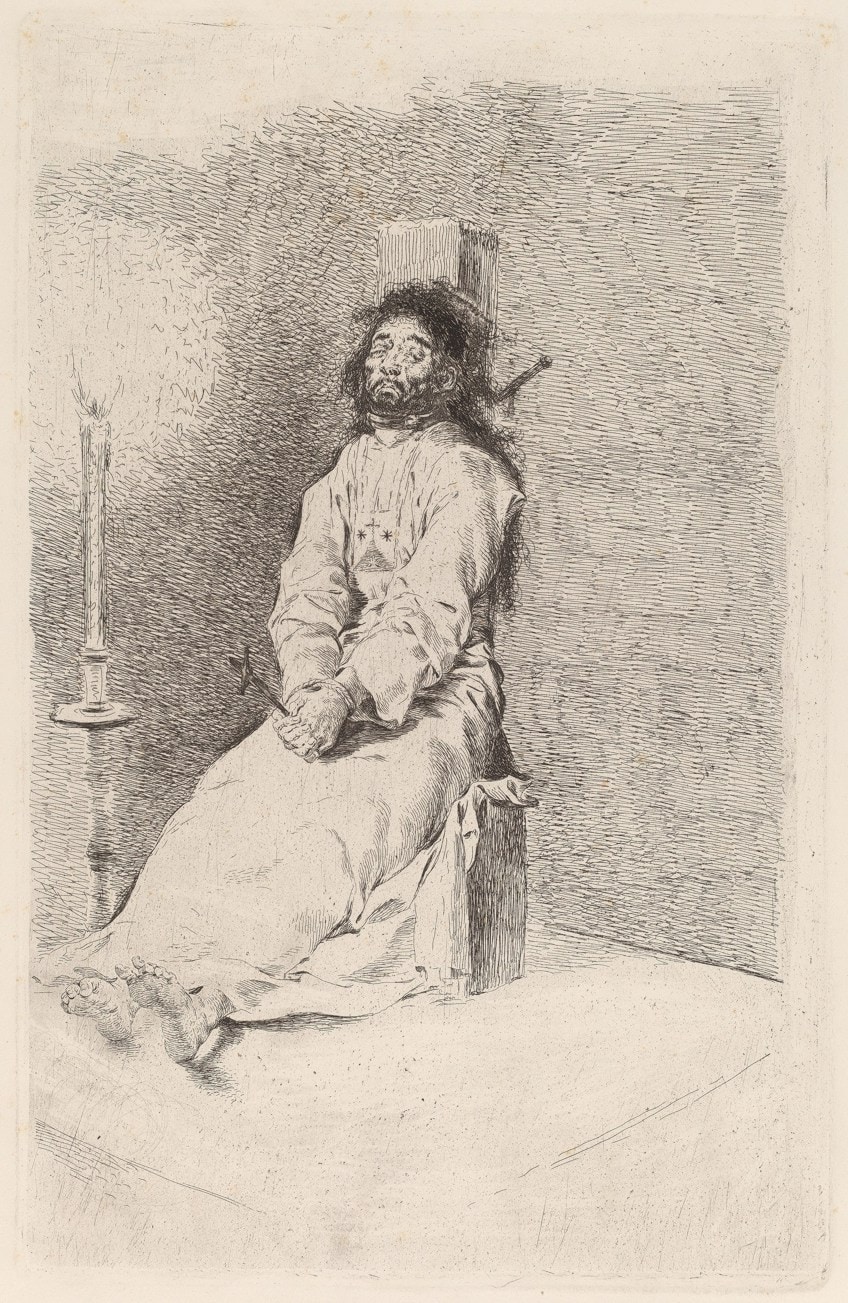

While many of his peers considered Goya’s efforts to duplicate and mimic the latter painter as foolishness, he had privy to a vast variety of the long-dead artist’s paintings that had been held in the royal library. Nevertheless, the young man was to master etching, a media that would expose both the real depths of his creativity and his political ideas. Goya’s etching of The Garroted Man (1775–78) was his biggest project to date, and it foreshadowed his subsequent Disasters of War collection (1810 and 1820).

Goya was afflicted with illnesses, and his disease was exploited against him by his competitors, who were envious of any painter thought to be gaining in prominence. A few of the larger cartoons, such as The Wedding (1791-92), were rather enormous and had tested his physical stamina. Goya, ever ingenious, turned this disaster around, stating that his sickness had given him the knowledge to create more intimate and casual works. Nevertheless, he found the method restrictive since it did not enable him to depict intricate color transitions or textures, and it was incompatible with the impasto and glaze methods he was using on his paintings at the time.

The tapestries appear to be observations on human sorts, style, and trends.

Spanish Painter Goya’s Work as a Court Painter

The Count of Florida Blanca asked Goya to create his portrait in 1783. He became acquainted with the King’s half-brother Luis and worked on portraits of both the Infante and his relatives over two seasons. During the 1780s, his network of clients expanded to also include the Duke and Duchess of Osuna and other significant persons from the monarchy who he portrayed. In 1786, Goya was hired as an artist for King Charles III. In 1789, Goya was named court painter to Charles IV.

The next year, he was promoted to First Court Artist, with a wage of 50,000 Reales and a carriage stipend of 500 Ducats.

He created paintings of the monarch and queen, as well as Manuel de Godoy, the Prime Minister of Spain, and a number of other aristocrats. His pictures are renowned for their lack of flattery; his Charles IV of Spain and His Family (1801) is a particularly harsh evaluation of a ruling household. The painting is viewed as humorous by modern interpretations; it is supposed to highlight the hypocrisy underlying Charles IV’s authority. His wife Louisa was supposed to have wielded actual authority throughout his rule, thus Goya put her in the middle of the group photo.

The painter may be seen peering out at the audience from the rear left of the picture, while the artwork behind the family represents Lot and his daughters, reflecting the core theme of depravity and rot. Goya received assignments from the Spanish nobility’s highest echelons. In 1801 he painted Godoy as part of a contract to celebrate the triumph over Portugal in the short War of the Oranges. Even though Goya’s 1801 image is widely seen as sarcasm, the two were friends.

The Middle Period of Francisco Goya’s Works

The Nude Maja (c. 1797–1800), the first of a two-painting series, has been defined as “the first truly obscene life-size feminine nude in the history of Western art,” with no attempt at metaphorical or legendary significance. The second painting is known as The Clothed Maja (between 1800 and 1807). The Majas’ identity is unknown. The most often reported models are the Duchess of Alba, with whom Goya was rumored to have had a romance, and Pepita Tudó, Manuel de Godoy’s mistress.

Neither option has been proven, and the images are more likely to be an exaggerated synthesis.

Godoy possessed the works, which were never formally displayed during Goya’s life. Ferdinand VII took all of Godoy’s possessions after his collapse from authority and banishment in 1808, and the Inquisition seized both pieces as “inappropriate” in 1813, giving them to the Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in 1836. In 1798, he created dazzling and airy sceneries for Madrid’s Chapel of San Antonio de la Florida. Several of them show miracles performed by Saint Anthony of Padua in the heart of modern Madrid.

An untreated ailment rendered Goya deaf sometime in 1793. While the aim and mood of his art altered, he grew more reclusive and contemplative.

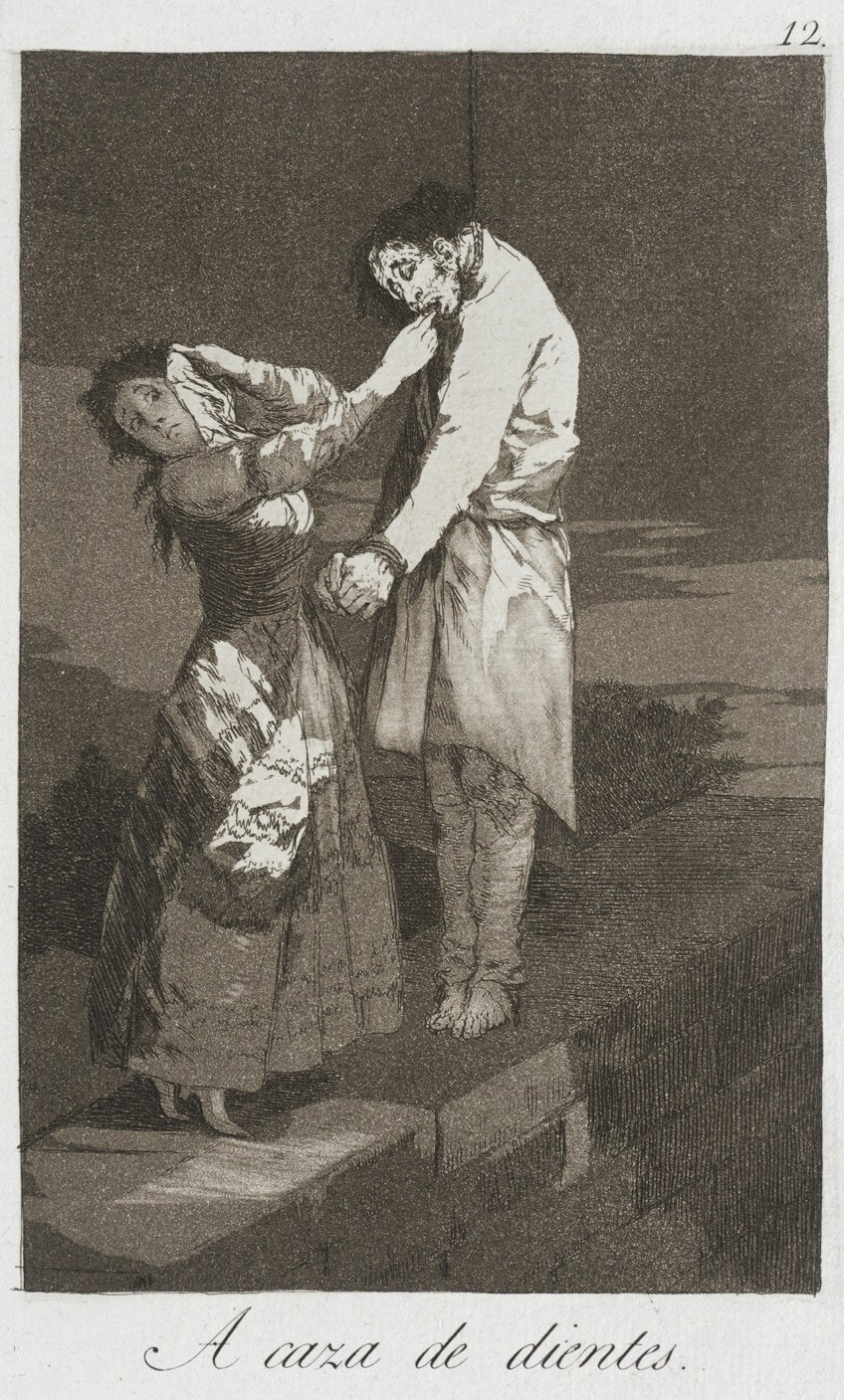

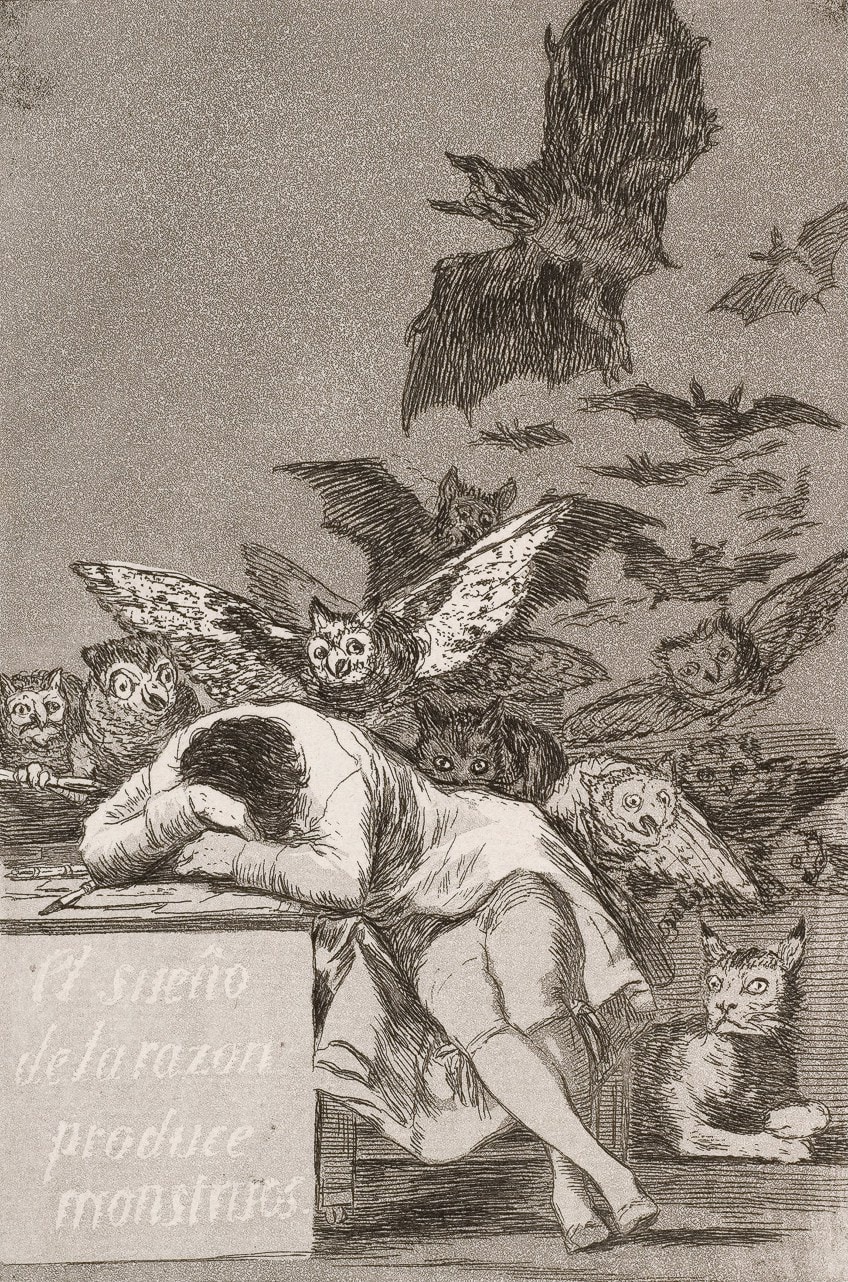

Goya began the Caprichos collection of aquatint etchings in 1799, which he created alongside more formal orders for portraiture and devotional artworks. Goya released 80 Caprichos images in 1799, illustrating “the many faults and absurdities to be found in every developed civilization, and from the ordinary biases and deceptive activities which tradition, inexperience, or self-interest have rendered normal.” The text “The slumber of logic breeds demons” helps to explain the images in these artworks. These are not entirely depressing; they also show the creator’s incisive sarcastic humor, as shown in works of art such as Out Hunting for Teeth (1799).

Goya’s cognitive and emotional deterioration appears to have occurred a few weeks after France declared war on Spain. “The sounds in his brain and deafness aren’t resolving,” a colleague noted, “but his sight is substantially better and he is again in command of his stance.” These symptoms might be the consequence of long-term viral encephalitis, or they could be the result of a succession of mini-strokes caused by high blood pressure and affecting the brain’s auditory and equilibrium systems.

Tinnitus, bouts of unbalance, and increasing deafness are all symptoms of Ménière’s illness.

It is conceivable that Goya has been afflicted by cumulative lead poisoning since he used huge amounts of lead white in his works, both as a canvas preparation and as a principal pigment, which he crushed himself. Other postmortem diagnoses hint to delusional psychosis, probably caused by brain damage, as demonstrated by significant alterations in his works following his recuperation, resulting in the “black” paintings.

Goya’s unusual ability to portray his inner troubles as a horrible and spectacular vision that speaks globally and enables his viewers to find their own closure in the visuals has been acknowledged by scholars.

The Peninsula War Period

In 1808, the French troops attacked Spain, sparking the Peninsular War. The degree of Goya’s affiliation with the courts of the “Attacker King,” Joseph I, Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother, is unknown; he painted works for French customers and appeasers while remaining impartial during the battle. Following the return of King Ferdinand VII of Spain in 1814, Goya denied any participation with the Invaders. By the time his wife Josefa died in 1812, he had completed The Second of May 1808, one of Goya’s war paintings, as well as the series of etchings afterward known as The Disasters of War.

In 1814 Ferdinand VII traveled back to Spain, but his relationship with Goya was strained.

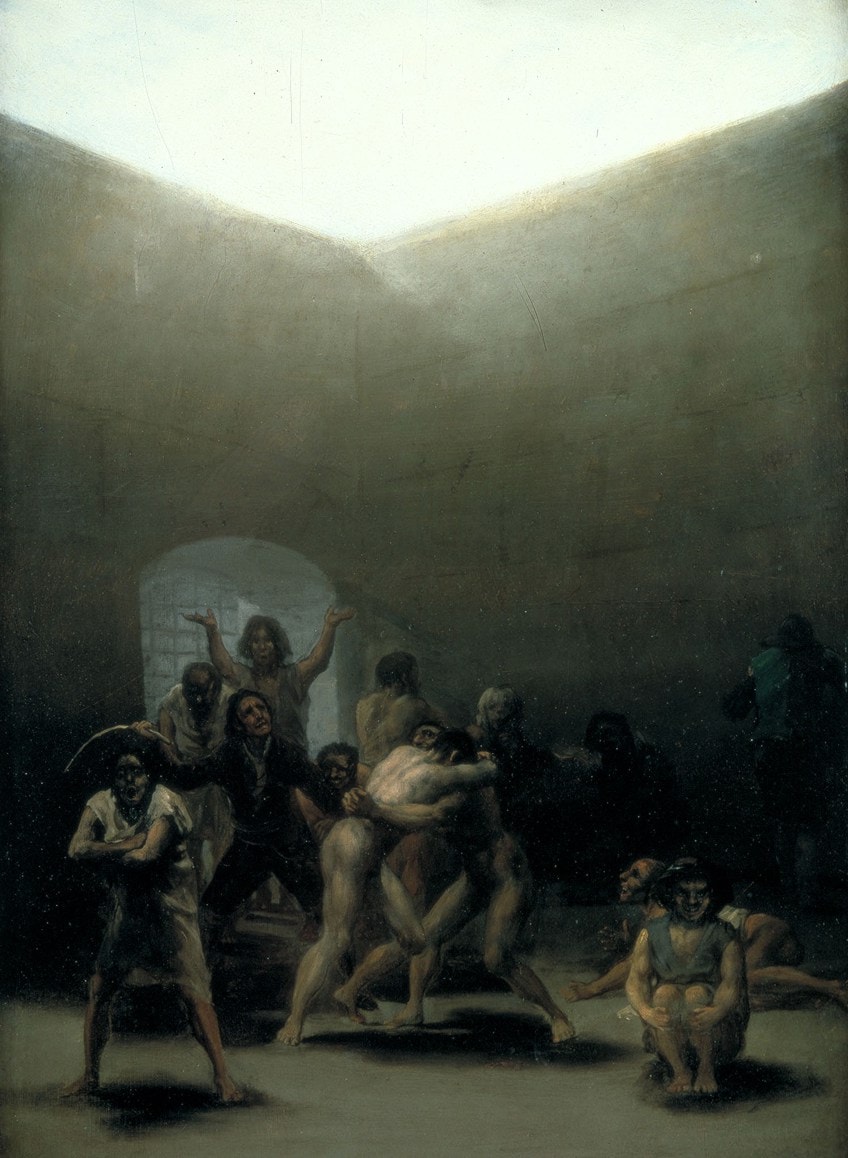

In 1794, Goya finished a series of 11 tiny paintings on tin that marked a fundamental shift in the mood and content of his work, drawing from the darker and melodramatic worlds of fantasy and horror. Yard with Lunatics is a fictitious depiction of isolation, anxiety, and social exclusion. The criticism of cruelty toward inmates (whether criminals or crazy) is a theme explored by Goya in later pieces that center on the deterioration of the human person.

This was one of Goya’s earliest cabinet works, in which his previous pursuit of idealized perfection gave way to an investigation of the link between reality and imagination that would concern him for the rest of his life. He was going through a psychological breakdown and suffering from a long-term medical sickness, and he acknowledged that the series was made to mirror his own self-doubt, worry, and dread of losing his mind.

The pieces, according to Goya, served to “engage my thoughts, plagued as it is by meditation of my afflictions.” He described the collection as consisting of images that “usually find no space in contracted artworks.”

Even though he did not state his desire in Goya’s war paintings The Disasters of War, scholars see them as a graphic opposition against the abuse of the 1808 Dos de Mayo Uprising, the resulting Peninsular War, and the anti-liberalism movement that followed the renewal of the Bourbon aristocracy in 1814. The images are unpleasant, even morbid in their portrayal of wartime tragedy, and express offended humanity in the midst of death and devastation. They were only issued 35 years after his passing, in 1863.

Only afterward was it likely seen ethically acceptable to release a series of paintings criticizing both the Frenchmen and the reinstated Bourbons.

The initial 47 plates in the sequence depict combat situations and the effects of the battle on particular troops and citizens. The repercussions of the hunger that struck Madrid in 1812, before the town was recovered from the French, are depicted in the middle part. The last 17 exemplify liberals’ terrible disillusionment when the reinstated Bourbon monarch, aided by the Catholic clergy, repudiated the Spanish Constitution of 1812 and resisted both political and ecclesiastical change.

Goya’s depictions of brutality, famine, humiliation, and shame have been regarded as a “stupendous blooming of wrath” since their initial release.

The Black Paintings Period

Details of Goya’s later years are few, and ever politically conscious, he hid a majority of his paintings from this era, preferring to create in solitude. Goya was plagued by a dread of old age and lunacy, the latter likely due to stress produced by an undiscovered ailment that rendered him deaf in the early 1790s. Goya was a famous and spectacularly positioned artist who retreated from public life in his later years. He resided in near-solitude near Madrid on a farm transformed into a workshop beginning in the late 1810s.

According to scholars, Goya felt estranged from the political and social tendencies that followed the reinstatement of the Bourbon monarch in 1814, and he saw these advances as regressive tools of societal control. He appears to have agitated against what he perceived as a strategic withdrawal into Medievalism in his unpublished art.

He is said to have hoped for religious and political transformation, but he, like so many liberals, was disappointed when the reinstated Bourbon king and Catholic hierarchy repudiated the Spanish Constitution.

He finished his 14 Black Paintings at the age of 75, isolated and physically and mentally in misery, all of which were done in oil straight into the plaster walls of his residence. Goya did not plan for the artworks to be displayed, did not write about them, and most likely did not speak about them. Owner Baron Frédéric Émile d’Erlanger took them down and placed them on canvas support about 1874, 50 years after his demise. Many of the pieces were considerably changed during the repair, and what remains are “at best a rough replica of what Goya created,” according to Arthur Lubow. One of the paintings from this series is Witches Sabbath (1798).

Further Reading

There is much to learn about Francisco Goya’s paintings and life. If you are interested in learning more about Francisco de Goya’s biography or artwork, we can suggest the following books. These books cover the life of Goya the artist, as well as the artworks created by the Spanish painter Goya.

Goya: Order & Disorder (2014) by Stephanie Stepanek

His work’s multi-layered and changing interpretations have rendered him one of the nation’s most researched painters. Few, though, have undertaken the arduous task of examining his work as an artist, printmaker, and draughtsman across mediums and space. This book provides precisely that, providing a complete and comprehensive view of Goya’s most significant painting, prints, and sketches through the ideas and images that the painter was constantly challenged or fascinated with.

- A comprehensive and integrated view of Goya's best works

- From the research for the largest Goya art exhibition in America

- This book takes a fresh look at one of the greatest artists in history

Francisco de Goya (2022) by Martin Schwander

Francisco de Goya was one of the last wonderful court painters and a substantial trendsetter for contemporary art; now, the Fondation Beyeler, in cooperation with the Museo Nacional del Prado, has assembled one of the most comprehensive expositions of his artwork from outside Spain, a significant occasion honored by this momentous edition. Over the course of his more than 60-year career, Goya served as an insightful spectator of the spectacle of rationality and madness, visions and horrors.

And that concludes our look at Francisco de Goya’s biography and artwork. Francisco Goya’s paintings helped to shed light on the political upheavals that were occurring during his lifetime. Spanish Painter Goya focused on individualism, creativity, and feeling, which is particularly visible in his engravings and later personal works.

Take a look at our Francisco Goya paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Goya’s Dog Painting?

Goya’s dog painting is known simply as The Dog. It was created in 1823 and is now exhibited at the Museo Nacional del Prado. The poor animal, living alone, is part of his Black Paintings series. There are several explanations for this image, including the dog being associated with the hellish character who accompanies the deceased souls to the afterlife, or the dog being a sign of desertion and abuse.

What Were Some of Goya’s Accomplishments?

Goya’s official portraiture of the Spanish Royalty was created in a sumptuous virtuoso manner, emphasizing the imperial household’s luxury and authority. The compositions, on the other hand, have been viewed to convey disguised, even subtle, critiques of the ineffective emperors and their coterie. Goya is regarded as one of the best printmakers of all history, known for his accomplishments in engraving and aquatints. During his tenure, he made four main printing portfolios. These pieces, maybe more than his canvases, reveal the creator’s uniqueness and his actual feelings regarding the political and social developments of the time. His etchings range in subject material from dreamy to macabre, factual to imagine, and funny to sharply sarcastic.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Francisco de Goya – Father of Unflinching Spanish Realism.” Art in Context. November 11, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/francisco-de-goya/

Meyer, I. (2021, 11 November). Francisco de Goya – Father of Unflinching Spanish Realism. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/francisco-de-goya/

Meyer, Isabella. “Francisco de Goya – Father of Unflinching Spanish Realism.” Art in Context, November 11, 2021. https://artincontext.org/francisco-de-goya/.