Famous Marble Statues – Discover 10 Iconic Marble Masterpieces

Making marble sculptures is often regarded as the oldest art form. Marble carvings are said to even be older than paintings. Since its origins in the ancient world, it has spawned many notable marble sculpture artists. In the list below, we will focus on the most famous marble statues ever produced!

Table of Contents

- 1 Our List of the Most Famous Marble Statues

- 1.1 Elgin Marbles (438 BCE) by Phidias

- 1.2 Venus de Milo (130 BCE) by Alexandros of Antioch

- 1.3 Augustus de Primaporta (1st Century) by Unknown

- 1.4 Zuccone (1425) by Donatello

- 1.5 David (1504) by Michelangelo

- 1.6 The Rape of Proserpina (1622) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

- 1.7 Modesty (1752) by Antonio Corradini

- 1.8 Seated Voltaire (1778) by the Workshop of Jean Antoine Houdon

- 1.9 Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss (1793) by Antonio Canova

- 1.10 Ugolino and His Sons (1860s) by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

- 2 Frequently Asked Questions

Our List of the Most Famous Marble Statues

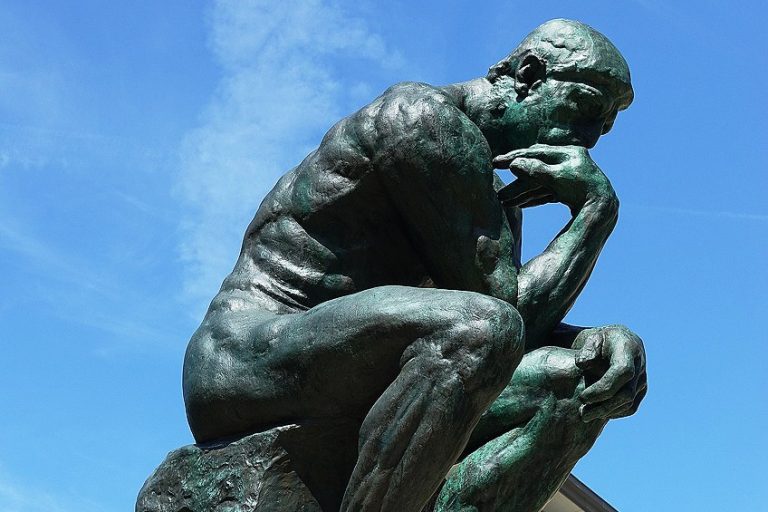

Marble sculptures have helped people understand civilization and culture. It is a fantastic medium for story-telling, allowing for a far more intimate relationship with the public. Marble has been a favorite material for sculptors throughout antiquity. This material, which dates back to ancient Greece and Rome, has various qualities that lend itself to the skill of colossal sculpture.

Marble outperforms its more prevalent geological neighbor limestone in its capacity to take in light before refracting it, resulting in a smooth and appealing aesthetic impression that is well suited to the portrayal of human flesh.

Pure white marble is the most prevalently used form of marble for sculpting. Colored varieties are mostly used for decoration. Because of the hardness, it is possible to sculpt marble without too much effort. Below is our personal list of the most famous marble statues ever made.

Elgin Marbles (438 BCE) by Phidias

| Artist | Phidias (490 – 430 BCE) |

| Date Created | 438 BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 7500 |

| Location | British Museum, London, United Kingdom |

Pentelic marble is the major competitor of Parian marble. Pentelic marble has a little yellow hue in addition to its pure white look. This has resulted in an attractive property of glowing with a golden tint when exposed to direct sunshine. Today, it is primarily mined on the neighboring island of Paros, Naxos, in the highlands near the settlement of Kinidaros.

The majority of the Parthenon sculptures are made of Pentelic marble, which was discovered near Athens. The Elgin Marbles are perhaps the most well-known specimens of Pentelic marble.

They are a group of classical Greek marble statues created by the sculptor and architect Phidias and his collaborators. They are from the Parthenon and other holy and ceremonial monuments constructed on Athens’ Acropolis in the 15th century BCE. In the early 19th century, Lord Elgin, a British diplomat, took the sculptures from the majestic Parthenon temple. He was the envoy to the Ottoman Empire, which dominated Greece at the time. Lord Elgin is claimed to have overseen the removal and shipment of the marble in 170 boxes to the UK starting in 1801.

Venus de Milo (130 BCE) by Alexandros of Antioch

| Artist | Alexandros of Antioch (130 and 100 BCE) |

| Date Created | 130 BCE |

| Medium | Parian marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 240 |

| Location | Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

The Venus de Milo is a marble sculpture of Aphrodite, the Greek goddess. Part of the fascination with this famous sculpture today stems from the fact that, while well-preserved, it is missing both of its feet, arms, and earlobe. She is seen half-dressed with a naked torso. Originally, the piece was credited to the 4th-century sculptor from Athens, Praxiteles. The sculpture is currently assigned to Alexandros of Antioch, because of the rediscovery of an inscription on its foundation.

Venus de Milo’s reputation owes greatly to a huge propaganda campaign by the French government in the 19th century, and she has an intriguing history tied to France’s cultural legacy.

The statue was installed in the Louvre following its shipment to France from Greece under Napoleon Bonaparte’s supervision. It was during this period that France’s national museum started to encounter several obstacles over the repatriation of particular artworks. Venus’s twisted body and modernized draperies provide her with immense grandeur. This marble sculpture exemplifies the Hellenistic sculptural tradition’s intellectual characteristics and dependence on prior works.

Augustus de Primaporta (1st Century) by Unknown

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date Created | 1st century |

| Medium | White marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 208 |

| Location | Vatican Museums, Vatican City |

Because of its intimate links with Greek sculpture, the examination of Roman sculptures is often considered more complex. Many Roman sculptures are only known as Greek “copies”. Art historians used to think that this copying was an indication of the Roman creative imagination’s limitations. By the end of the 20th century, however, Roman art had begun to be re-evaluated on its own terms. Augustus de Primaporta’s famous marble sculpture is an example of this kind of artwork from Roman artistic history.

Augustus, the subject of the monument, rose rapidly to power to become Rome’s first emperor after over a century of civil strife.

Augustus believed strongly in the value of public art and utilized his sponsorship of the creative arts to support his newly established position of leadership. He had roughly 70 portrait sculptures made of himself. They all point to his aristocratic ancestry dating back to the founder of Rome. This 1st century CE marble figure was discovered in the remains of the home of Livia at Prima Porta and is currently on exhibit in the Vatican. It emphasizes Augustus’ military prowess and recalls the Republic’s prior golden period, which he vowed to return to during his rule.

Zuccone (1425) by Donatello

| Artist | Donatello (1386 – 1486) |

| Date Created | 1425 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | Unspecified |

| Location | Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence, Italy |

The figure’s large and angular head gave rise to the name Zuccone, which translates into Italian as “pumpkin”. The extraordinarily lifelike figure is tense and dressed in the flowing garments characteristic of most of Donatello’s prophets. His face is slightly slanted downward, giving the figure a humble air on his emaciated face. The story of Habakkuk may be found in the Hebrew Bible. There is scant information available concerning the prophet.

This gave Donatello greater artistic flexibility than was usual for other monuments with more definite histories.

In the text, Habakkuk’s legacy was somewhat exceptional in that he was one of the few prophets to challenge the injustices that God permitted. Donatello’s marble sculpture’s sorrowful and inquisitive eyes must have been motivated by this knowledge. Donatello was said to have favored this piece. Vasari would subsequently recall Donatello’s fondness for the sculpture, claiming that while working, Donatello would look at Zuccone’s face, murmuring, “Speak!”.

David (1504) by Michelangelo

| Artist | Michelangelo (1475 – 1564) |

| Date Created | 1504 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 199 |

| Location | Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy |

Agostino Di Duccio, another Renaissance-era sculptor, had abandoned the large block of Carara marble from which this iconic sculpture was carved 40 years prior. He had begun some preliminary work on molding the feet, legs, and torso of the over six-tonne block of marble, but lacked the will and commitment to see the project all the way through to completion.

Michelangelo was encouraged to resume work on the piece in 1499 by the Guild of Wool in Florence, and it was finished in 1604. Michelangelo’s passion was marble sculpture.

He grew up with his babysitter and her husband who was a stone cutter after his mother died. Because his father owned a marble quarry, he spent a lot of time seeing stone being quarried and carved while also gaining hands-on experience at a young age. To Michelangelo and other artists, marble’s comparative translucency and softness in comparison to human flesh made it preferred over granite, limestone, and bronze for sculpting figures. The carving itself was done using a mallet and a chisel.

The Rape of Proserpina (1622) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

| Artist | Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598 – 1680) |

| Date Created | 1622 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 225 |

| Location | Borghese Gallery, Rome, Italy |

The god of the underworld in Greek mythology, abducts Proserpina, the daughter of the deity of fertility and harvest, Ceres in the massive marble group of Proserpina and Pluto. Her mother gains approval for her daughter to go back to Earth for part of the year and spend the other half in the Underworld by intervening with Jupiter. As a result, every spring, the ground greets her with a luscious carpet of flowers. The executions took place between 1621 and 1622. It was given to Cardinal Ludovisi by Cardinal Scipione in 1622 and stayed in his home until 1908 when it was bought by the Italian state and restored to the Borghese Collection.

Bernini expands the twisting position evocative of Mannerism in this group, paired with a feeling of dynamic energy (while pressing against Pluto’s face, Proserpina’s hand wrinkles his skin and lets his fingertips burrow into his victim’s skin).

The entire group is seen from the left, with Pluto taking a swift and mighty stride and grabbing Proserpina; from the front, he looks triumphant, bearing his prize in his arms; from the opposite side, one sees Proserpina weeping as she prays to the heavens, the breeze blowing in her hair, and the three-headed dog, Hades’ guardian, barking. Various scenes from the tale are thus encapsulated in a single marble sculpture.

Modesty (1752) by Antonio Corradini

| Artist | Antonio Corradini (1688 – 1752) |

| Date Created | 1752 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 195 |

| Location | Cappella Sansevero, Naples, Italy |

Corradini spent much of his time in Venice, but he also visited Naples and Vienna before dying in 1752. Corradini’s series of shrouded female nudes ended with modesty, a theme he cultivated and perfected throughout his career. In his commissioned pieces, his mastery of the material of marble may be observed in the more skillful rendering of virtually weightless drapery over human flesh.

In the chapel, modesty is placed on a pedestal and may sometimes be lost in the grandeur of the room and its surrounding statues produced by other artists.

Raimondo intended that this memorial represent his mother’s sudden death while he was just a year old. The figure is standing in a contrapposto position, with more weight on one foot than the other. This stance provides her with human-like characteristics as well as the feeling as if she is in the midst of an action. This motion is also reflected in the way her classical drapery drapes across her torso. Artists in 18th-century Italy, like Corradini, were particularly concerned with depicting movement.

Seated Voltaire (1778) by the Workshop of Jean Antoine Houdon

| Artist | Jean Antoine Houdon (1741 – 1828) |

| Date Created | 1778 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 35 |

| Location | Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

Houdon appears to have created a fast drawing of Voltaire casually seated in the sculptor’s workshop in March 1778, while documenting Voltaire’s characteristics for the famed writer’s portrait bust. Voltaire’s niece, a woman by the name of Mme Denis, commissioned a lifesize marble sculpture based on the design, which had been widely praised by visitors to Houdon’s workshop.

The marble was finished in 1781, although a miniature gilt-bronze maquette replica planned for Catherine the Great’s collection was presented in the Salon in 1779.

Houdon’s studio went on to construct multiple reproductions of this sketch model, one of which is housed in the Museum and bears the sculptor’s atelier stamp on its back. The contrast between the two significantly different versions— the fine-tuned final conception and the live sketch—is interesting and informative, illustrating how the artist modified “reality” to create an eternal image. The first maquette is more inactive, and less alert than the larger variants; it depicts the bald-pated philosopher sitting erect, left hand passively lying on the chair arm.

Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss (1793) by Antonio Canova

| Artist | Antonio Canova (1752 – 1822) |

| Date Created | 1793 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 168 |

| Location | Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

Cupid brings Psyche’s lifeless corpse back to life at this point. The two figures are composed in a pyramid shape, which gives the marble sculpture a sturdy structure. Cupid is on one knee on a rock, clutching Psyche by the breast and head. He has enormous wings that point upwards into the air and a quiver on his back. Psyche leans up and places her hands on Cupid’s head. They are ready to kiss, so she lets her head swing back. Her hair cascades down to the ground. Her lower body is covered in a cloth. This narrative represents the great efforts and problems that a human must face in order to obtain immortality and happiness.

Observe how precisely Canova fashioned the supple bodies of the figures. This smooth quality contrasts wonderfully with the wrinkled textures of Psyche’s covering and the roughness of the boulder on which they recline.

A handle at Psyche’s right foot was initially provided to turn the marble sculpture around since it was important to observe this artwork from all perspectives. Another version of this sculpture was built by Antonio Canova for Prince Yusupov, the Russian art collector. This version was created in 1796 and is presently housed at Saint Petersburg’s Hermitage Museum.

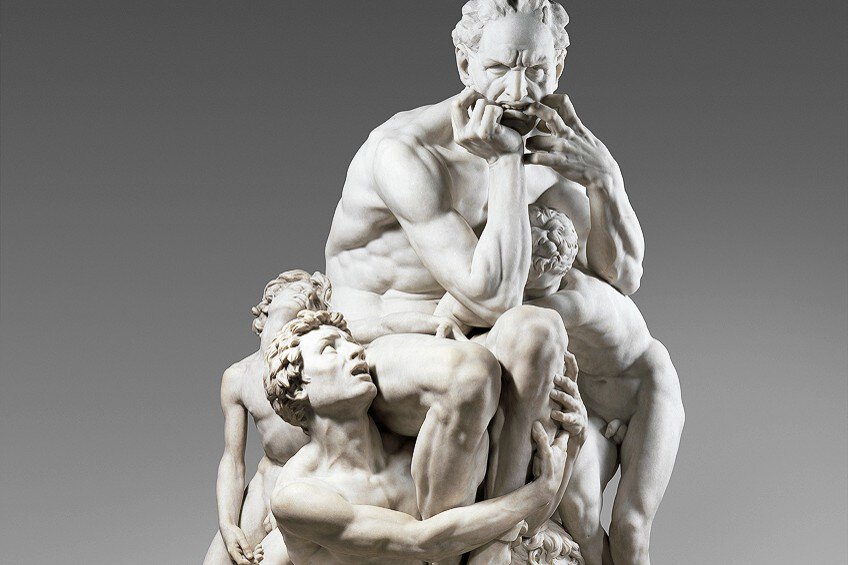

Ugolino and His Sons (1860s) by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

| Artist | Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827 – 1875) |

| Date Created | 1860s |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 197 |

| Location | Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

Ugolino and his children are sentenced to death by being starved of food. This sculpture depicts the precise moment when Ugolino contemplates cannibalism. He is represented with his four children, all nude, yet he ignores them in this marble sculpture. He’s staring into the horizon, biting his fingers and pulling his lip down with them. He rests his chin on the palm of his hand. He is thinking about the repercussions of his sins.

Despite the fact that he is starving to death, he is molded like a muscular individual. He is leaning forward, his feet stacked on top of each other. The four children are in various levels of distress, and they ask their father to eat them so that he can survive.

The oldest boy appears to be the most active. He is pleading with his fingers in the fleshy part of Ugolino’s calf. On the right, the second oldest child is similarly clutching his father with both of his hands. The second youngest child on the left is sitting on top of his elder sibling and has already expended most of his available energy. His left arm is resting on his father’s leg. The youngest boy is on the right at the bottom, and despite the fact that he is the only one with a serene look, he seems to be dead.

That completes our list of famous marble statues created through the centuries. These remarkable marble carvings were produced by the top marble sculpture artists of their time. They were so finely produced, that they are still highly admired even to the present day. From being the oldest medium in art to a medium still popular today, marble statues will still be around long after we are gone.

Take a look at our marble statues webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Most Famous Marble Statues?

History is full of notable examples of famous marble statues. However, there are a few examples that stand above the rest. These include David (1504) by Michelangelo, Venus de Milo (130 BCE) by Alexandros of Antioch, The Rape of Proserpina (1622) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss (1793) by Antonio Canova.

Why Do Sculptors Enjoy Working With Marble?

The inherent beauty and elegance of marble is well known. It has a smooth texture and a light appearance that can enhance sculptures. Marble’s natural veining and patterns provide character and depth to the artwork, improving its visual appeal. Marble is a long-lasting material, making it suitable for producing sculptures. Marble sculptures may resist the test of time and keep their beauty for generations with appropriate preservation and care, as proven by countless famous marble statues that still exist today.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Famous Marble Statues – Discover 10 Iconic Marble Masterpieces.” Art in Context. August 31, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/famous-marble-statues/

Meyer, I. (2023, 31 August). Famous Marble Statues – Discover 10 Iconic Marble Masterpieces. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/famous-marble-statues/

Meyer, Isabella. “Famous Marble Statues – Discover 10 Iconic Marble Masterpieces.” Art in Context, August 31, 2023. https://artincontext.org/famous-marble-statues/.