Easter Island Statues – The Purpose Behind the Moai Statues

What are the Easter Island statues called and how old are the Easter Island statues? The Easter Island head statues of Rapa Nui are known as the Moai statues and they were sculpted sometime between the years 1250 and 1500. While half of them were carried and positioned along the perimeter of the island, the other half is still located in the quarry in which they were made, known as Rano Raraku. Let’s unearth the mysteries surrounding the Easter Island statues.

Table of Contents

The Easter Island Head Statues of Rapa Nui

| Artists | Rapa Nui craftsmen (c. 1250 – 1500) |

| Date | (c. 1250 – 1500) |

| Medium | Volcanic tuff |

| Height (meters) | Various sizes, tallest 10 meters |

| Location | Rapa Nui, Polynesia |

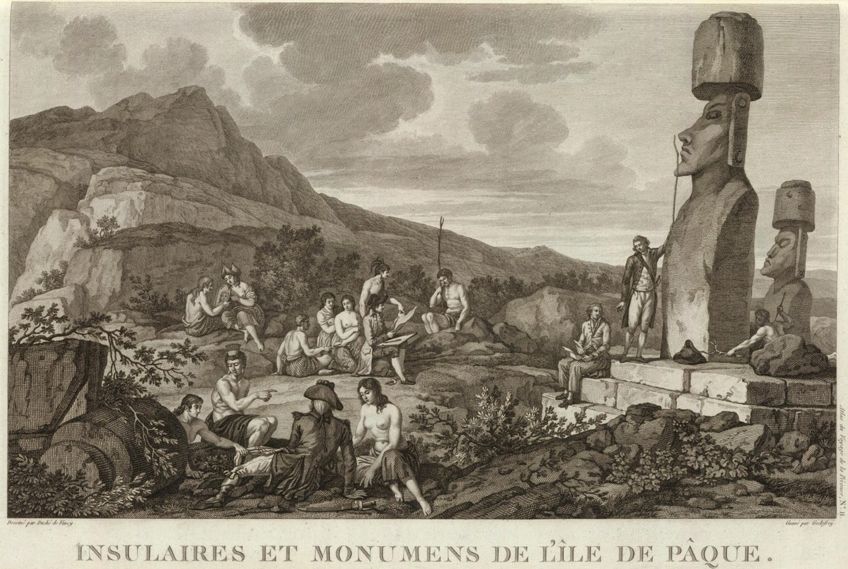

Nearly all moai have disproportionately enormous heads that are three-eighths the size of the entire statue. The lifelike faces of the Moai statues represent the idolized ancestors. When Europeans arrived on the island for the first time in 1722, the Easter Island heads were still guarding their clan territories located inland, but by the late 19th century, all of them had toppled. From the late 18th to the early 19th centuries, the statues of Rapa Nui were destroyed, probably as a result of interaction with Europeans or internal tribal conflicts.

Description of the Moai Statues of Rapa Nui

The Moai statues of Rapa Nui are monolithic monuments whose understated design is reflective of Polynesian features. Volcanic tuff was used to create the Easter Island heads. First, the shape of the figures would be chiseled out of the volcanic tuff wall, leaving just the image required. The oversized heads follow a three-to-five ratio between the trunk and the head, with heavy brows and extended noses with a characteristic fish-hook-shaped nostril curl, a sculptural attribute congruent with the Polynesian belief in the holiness of the chief head.

A narrow pout protrudes from the lips. The ears, like the nose, are oblong and elongated in shape.

The jaw lines contrast with the shortened neck. The torsos are massive, and the clavicles are occasionally faintly delineated in stone. The arms are carved in bas relief and lay against the body in a variety of postures, with hands and long thin fingers lying along the hip crests, meeting at the hami, and the thumbs occasionally pointing towards the navel. Typically, the backs of the Easter Island statues are not detailed, although they may have a girdle and ring design on the lower back and buttocks.

The statues of Rapa Nui, with the exception of one kneeling moai, lack plainly discernible legs. The Moai statues are whole-body sculptures, yet certain popular literature frequently refers to them as “Easter Island heads”. This is due in part to the exaggerated size of most heads and in part to the fact that a number of the sculptures on Rano Raraku’s slopes, most of which are submerged up to their shoulders, are the iconic pictures for the island depicting upright statues. It has been discovered that several of the “heads” at Rano Raraku had marks on their bodies that had been preserved from erosion by burial.

Characteristics of the Statues of Rapa Nui

The Moai statues are distinguished by their broad noses and massive chins, as well as rectangular ears and large eye slits. Their bodies are usually squatting, with their arms positioned in various postures and no legs. The vast majority of ahu statues are situated near the shore, facing inward towards the settlement. Some inland statues exist, like Ahu Akivi.

These Moai statues face the village, but given the island’s tiny size, they also seem to face the coast.

Eyes

Sergio Rapu Haoa and his colleagues revealed in 1979 that the elliptical sockets for the eyes were intended to contain coral eyeballs with either red scoria or black obsidian pupils. The finding was discovered by gathering and reconstructing broken pieces of white coral found at various locations. Following that, previously unclassified findings at the Easter Island museum were re-examined and reclassified as fragments of eyes. It is assumed that the Moai statues with carved eye holes were presumably assigned to Ahu and ceremonial places, implying that the Moai design was associated with a selected Rapa Nui hierarchy until its collapse with the emergence of the religion centered on the Tangata Manu.

Markings

The surfaces of the Easter Island statues were polished smooth when they were initially carved by rubbing them with pumice. Because the readily worked tuff from which most of the statues were carved is rapidly eroded, the greatest location to observe surface detail is on the rare basalt Moai or in pictures and other archaeological documents of Moai surfaces preserved by burial sites. Easter Island statues with less degraded backs and buttocks frequently have designs engraved on them. The 1914 Routledge expedition revealed a sociocultural link between these drawings and the island’s customary tattooing, which had been suppressed by priests a half-century before.

Until a recent DNA study of the locals and their predecessors, this was considered critical scientific proof that the Moai statues were carved by Rapa Nui rather than a different South American culture.

Some of the Easter Island heads had been painted. One of the statues in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection was adorned with a reddish hue. Hoa Hakananai’a was painted white and maroon until it was transported from the island in 1868. It is presently held at the British Museum in London, however, calls for its return to Rapa Nui have been made. The more modern Moai wore head cylinders known as pukao, which represented the chieftains’ topknot. According to local legend, the mana was kept in the hair. The pukao were carved from red scoria, an extremely light rock mined in Puna Pau. In Polynesia, the color red is considered holy. The addition of pukao suggests that the Moai has a higher rank.

Symbolism

Many archaeologists believe the sculptures were religious and geopolitical emblems of power and authority. But they were more than just symbols. They were literal stores of spiritual energy to the people who built and used them. Carved wooden and stone artifacts in ancient Polynesian religions were thought to be energized by a mystical spiritual element called mana when properly crafted and ritualistically prepared. Archaeologists think the sculptures depicted the forefathers of the ancient Polynesians. The Easter Island statues face away from the water and toward the communities as if to keep an eye on the inhabitants. The seven Ahu Akivi, which look out to the ocean to assist visitors to locate the island, are an exception. According to folklore, there were seven people who were waiting for their monarch to arrive. According to 2019 research, ancient people thought that quarrying the Moai was tied to enhancing soil fertility and hence important food sources.

History of the Easter Island Statues

The Polynesian settlers of the region produced the sculptures between 1250 and 1500. In addition to symbolizing departed ancestors, the Easter Island heads may have been considered as the manifestation of strong current or past chiefs and vital lineage status markers after they were placed on Ahu. “The greater the figure set upon an Ahu, the greater amount of mana the chieftain who ordered it possessed”, said one. The race for the largest statue has always been present in the Easter Islanders’ culture.

The different sizes of the statues provide evidence. Completed Moai statues were transported to Ahu, primarily on the seashore, and raised, often with pukao on their heads.

The statues must have been exceedingly costly to create and move; not only would the sculpting of each figure require time and effort, but the final product would also have to be transported to its ultimate site and erected. The Rano Raraku quarries seem to have been deserted suddenly, with a littering of stone tools and numerous complete statues outside the quarry waiting to be transported and nearly as many unfinished sculptures remained in place as were erected on Ahu. Because of this, there was 19th-century conjecture that the island was the ruins of a submerged continent and that the majority of completed statues were submerged.

That notion has long been disproven, and it is now accepted that:

- Some figures were rock carvings that were never meant to be finished.

- Some were unfinished because when carvers found inclusions, they would abandon a partly statue and begin a new one. Tuff is a soft rock that contains occasional chunks of considerably harder rock.

- At Rano Raraku, several completed monuments were placed permanently instead of temporarily installed.

- When the statue-building era ended, several were left unfinished.

Transportation

Because the island was essentially treeless when Europeans first arrived, the relocation of the sculptures was a mystery; pollen study has recently proved that the island was almost entirely wooded until 1200 CE. By 1650, tree pollen had vanished from the record. How the Moai statues were moved about the island remains a mystery. Previously, academics considered that the operation would almost probably need human labor, ropes, and potentially rollers or wooden sleds, as well as leveled paths throughout the island. Another idea holds that the Moai were rolled to their locations on top of logs. If that presumption is accurate, 50 to 150 people would be needed to move the statues.

Based on information from the archaeological record, the most recent study demonstrates that the figures were connected with ropes from two sides and made to “walk” by rotating them from side-to-side while being pushed forward. While “walking” the statues, they would also sing.

Coordination and coherence were critical; therefore, they devised a mantra in which the beat assisted them in pulling at the exact time required. Oral histories describe how different individuals harnessed heavenly power to make the sculptures walk. According to the oldest legends, a monarch named Tuu Ku Ihu relocated them with the assistance of the deity Makemake, but later myths speak of an individual who lived alone on the mountain and could move them as she pleased. Jo Anne Van Tilburg proposed in 1998 that by mounting the sled on greased rollers, more than half of that number could achieve it. She oversaw an effort to lift a nine-tonne statue in 1999. In two efforts to tow the Moai, a copy was mounted onto a sled fashioned in the shape of an A-frame and set on rollers, while around 60 individuals pulled on many ropes. The initial effort failed as the rollers continuously became stuck.

When the tracks were implanted in the earth, the second attempt was successful. This was done on level land with eucalyptus wood instead of native palm trees. the Kon-Tiki Museum, Thor Heyerdahl, and Pavel Pavel tested two of the statues in 1986. They “walked” the statue forward by tilting and swaying it from side to side with a cable around the base and another around the head, requiring eight people for the smaller sculpture and 16 people for the bigger, but the experiment was cut short owing to damage to the statues’ bases from breaking. Despite the experiment’s early termination, Thor Heyerdahl predicted that this approach for transporting a 20-tonne monument over Easter Island topography would enable 100 meters each day. Due to the claimed destruction to the base produced by the “shuffling” action, some researchers determined that it was most likely not the manner the statues were moved. At the same moment, archaeologist Charles Love tested a 10-ton duplicate.

His initial trial revealed that swaying the figure to walk it was too unsteady beyond a few hundred yards. He discovered that by setting the statue upright on two sled runners on log rollers, 25 men could move it 46 meters in two minutes. Further investigation in 2003 revealed that this strategy might explain purportedly properly spaced post holes where the sculptures were carried through rugged terrain. He proposed that the holes have erect posts along either side of the walkway so that when the figure passed between them, they could be utilized as cantilevers for poles to assist push the sculpture up a slope without the need for additional people tugging on the ropes, and likewise to slow it down the hill. When necessary, the poles might also serve as a brake.

Archaeologists Carl Lipo and Terry Hunt have established that the pattern of breakage, shape, and location of sculptures along prehistoric roadways is consistent with an “upright” concept for transportation based on comprehensive investigations of statues recovered along prehistoric highways. Lipo and Hunt contend that the craftsmen left the bases of the sculptures broad and curled at the front edge when they were cut in a quarry. They demonstrated that sculptures beside the road had a center of mass, causing them to tilt forward. The figure takes a “step” forward as it tilts forward, rocking sideways along its curving front edge. Large chunks are visible breaking off the bases’ sides.

They claim that the wide and curving base was chiseled down after the figure was “walked” along the road and put in the landscape.

All of this data speaks to an upright-positioned mode of transportation. Modern recreations have demonstrated that the statues were practically walked from the quarry to their intended locations using sophisticated ropework. People would have labored in groups to sway the statues back and forth, generating the walking motion and keeping the statues upright. If accurate, the fallen road statues were the consequence of the groups of balancers being unable to hold the Eastern Island statues upright, and it was likely impossible to raise the statues once pushed over – nonetheless, the argument persists.

The Birdman Cult

Easter Islanders used to have a supreme chief. Over time, power shifted from solitary chiefs to a warrior caste called the matatoa. The matatoa’s sign was a therianthropic creature that was half man and half bird; the distinguishing feature linked the sacred location of Orongo. The new cult sparked tribal wars over ancestor worship. Constructing the Moai statues was one way the islanders honored their ancestors; however, evidence shows that the production of Moai ceased during the height of the birdman worship.

The hundreds of petroglyphs etched with Makemake and birdman motifs are one of the most remarkable sights at Orongo. They have withstood the test of time, having been carved into solid basalt. It has been speculated that the images depict the victors of the birdman battle. More than 480 birdman petroglyphs have been discovered on the island, especially in the Orongo area. Orongo, the cult’s gathering place, was a perilous setting with a small ridge between a 300-meter plunge into the sea on one side and a massive crater on the other. Mata Ngarau, regarded as Orongo’s sacred site, was where birdman monks worshiped and sang for a successful egg search.

Sanctity of the Easter Island Statues

In 1722, Jacob Roggeveen, the first European traveler to the island, noted in his ship record that locals were worshiping the sculptures. According to appearances, the people lacked weapons; yet, he added, they depended in times of need on their gods or idols, which are placed in large numbers along the seashore, in front of which they fall down and beseech them. He described the sculptures as “all carved out of the stone”, and in the figure of a man, with large ears, ornamented on the head with a crown, but all carved with skill.

He made certain of the people priests because they showed greater regard to the gods than the rest, and they were much more dedicated in their ministering.

They might also be distinguished from the rest of the population by wearing large white plugs in their lobes, as well as having their heads completely shaved and hairless. Only Jacob Roggeveen has ever documented someone praying to the sculptures, implying that the monuments were worshipped before Europeans arrived. However, it was normal practice throughout the island to reuse fragments of existing sculptures while constructing new Ahu platforms. This appears to imply that the Moai statues were no longer considered sacred when the person they represented was forgotten.

The Toppling of the Easter Island Statues

All of the statues that had been built on Ahu fell at some time following Jacob Roggeveen’s arrival in 1722; Abel Aubert du Petit-Thouars noted the final standing sculptures in 1838, and by 1868 there were none left upright outside the half-buried ones on Rano Raraku’s outer slopes. Oral traditions include one narrative of a clan knocking down a solitary Easter Island head in the middle of the night, but others relate to “earth-shaking”, and there is evidence that at least several of them were destroyed by earthquakes. Some of the Easter Island statues tumbled forward, concealing their faces, and frequently breaking their necks; others went over the rear of their bases.

The slave trade, which started on the island in 1862, decimated the Rapa Nui inhabitants. Within a year, the people who stayed on the island were ill, wounded, and devoid of guidance. The surviving few of the slave raids found themselves in the company of landing missionaries. The surviving population eventually turned to Christianity. Native Easter Islanders were gradually integrated as their body art and body paint were prohibited by the new Christian laws, after which they were removed from a part of their native territories and forced to live on a significantly smaller part of the island, whereas the rest was used for agriculture by the Peruvians.

The Human Effect on the Easter Island Heads

The great majority of the statues border the island’s shore, which is directly exposed to rising sea levels and coastal erosion induced by climate change. Rapa Nui foresaw this decades ago and erected sea barriers, some of which are eroding and need to be reinforced. The Rapa Nui people have historically been in control of that maintenance: it was the group’s obligation to perform things that safeguarded their places on a seasonal basis – they were meant to weed them before rituals, and they were supposed to fix the wall.

However, financial assistance for such renovations has been difficult to come by in recent years, particularly amid disagreements over authority between local communities, individual households, and the Chilean government.

Restoration and Preservation

Ten or more of the Moai statues have been taken from Easter Island and sent across the world, including those now on exhibit at the British Museum and the Louvre Museum. William Mulloy, an American archaeologist, investigated the manufacturing, shipping, and construction of Easter Island’s massive statues from 1955 to 1978. Mulloy’s Rapa Nui developments include the research and physical renovation of the Akivi-Vaiteka Complex and Ahu Akivi in 1960; the research and renovation of Ahu Vai Uri, Ahu Ko Te Riku, and the Tahai Ceremonial Complex in 1970; and multiple other archaeological assessments throughout the island.

The statues were listed in the United Nations Convention on the Protection of the World’s Natural and Cultural Heritage in 1972, and, as a result, were added to the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1995. Several groups have attempted to map the statues over the years, including work by Father Sebastian Englert and Chilean scholars. The Easter Island Statue Project researched and documented several of Rapa Nui’s Moai as well as items kept in museums across the world.

The project’s goal is to understand the figures’ original function, context, and significance, with the results being shared with Rapa Nui families and the island’s official organizations in charge of Moai conservation and preservation. Other researchers include Terry L. Hunt, Britton Shepardson, and Carl P. Lipo. A Finnish visitor chipped a portion of one statue’s ear in 2008. The traveler was fined $17,000 and barred from returning to the territory for three years. An unattended truck crashed into a Moai in 2020, shattering it and incurring “incalculable damage”.

A wildfire that burned approximately 200 acres in Rano Raraku in 2022 destroyed an unknown number of the Easter Island heads. Pedro Edmunds Paoa, the Mayor of Rapa Nui, indicated that the fire was lit on purpose. The fire destroyed hundreds of statues, primarily near the Rano Raraku quarry. Photographs of the Easter Island statues reveal more surface damage than in previous fires, which might imply breaking on the inside of the stone. Heavy rains may lead to the stone disintegrating in this situation.

The Rapa Nui inhabitants claimed that their chiefs were derived from the heavens and that after death, they would revert to a divine status. The Easter Island statues were erected to temporarily house the souls of their forefathers. The Ahu on which they perch was formerly the location of death ceremonies, and excavations have revealed burnt and interred human remains at several of them. There is a strong link between Rapa Nui’s Moai and comparable monoliths seen across Polynesia. Experts think these monuments are related to a similar faith, despite their differences in appearance. The Rapa Nui natives chiseled the Easter Island heads straight from Rano Raraku, an extinct volcano, using volcanic tuff, a porous stone consisting of hardened ash. The slave trade, colonization, and a number of plagues all took their toll. By around 1877, the population of the island had dropped to as few as 111 people. The population has recovered, with approximately 2,000 local people living there now in a town of roughly 7,000 people.

Take a look at our Easter Islands Heads webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Easter Island Statues Called?

The Easter Island Heads are known as the Moai statues of Rapa Nui. The Moai statue carvers were regarded as expert artisans and were rewarded for their efforts. Carvers took great care not to disturb spirits while building. The carvers are said to have started with the sides and front of a statue, then progressively separated the rear from the quarry rock. The figure was subsequently relocated downhill and erected upright in a pit, where the carvers finished its back and added petroglyphs to its surface. The Easter Island head would then be finished.

How Old Are the Easter Island Statues?

The residents of this island, also known as Rapa Nui, constructed the Moai statues between 1400 and 1650 CE. Many people refer to them as the Easter Island heads. This is a fallacy based on images of sculptures partially covered up by dirt in the volcano Rano Raraku. The reality is that all of these heads have whole bodies.

Why Were the Moai Statues Sculpted?

Moai sculptures were erected to commemorate the deaths of chieftains and other notable persons. They were put on rectangular stone slabs known as Ahu, which are graves for the persons depicted by the sculptures. The Moai sculptures were intentionally made with a variety of characteristics in order to preserve the appearance of the person they represented. The Moai statues were purchased from a single group of carvers. The purchasing tribe would compensate with whatever they had in plenty. Sweet potatoes, poultry, bananas, carpets, and obsidian implements are instances of trade products. Because a larger monument would be more expensive, bigger sculptures would also imply greater grandeur for the tribe, as it would demonstrate that the people are intelligent and hardworking enough to pay.

What Happened to the Statues of Rapa Nui?

All of the monuments that had been reported on were still standing when the first European ship landed on Easter Island in 1722. Later visitors claim that more sculptures have fallen throughout the years, and by the end of the 19th century, not a single figure remaind standing. The most widely accepted theory is that the statues were destroyed to humiliate the other tribe during the tribal conflicts. One rationale for this is that most Moai statues have fallen forward, face down into the dirt. There is also a folktale about a woman by the name of Nuahine Pkea Uri who possessed strong mana abilities and made the monuments fall in anger when her children denied her food.

What Tools Were Used to Carve the Easter Island Statues?

Toki, which are basic portable chisels, are used to carve the Moai figures. They have been discovered in large quantities throughout all excavations at Rano Raraku, notably surrounding the sculptures. The best toki are fashioned of hawaiite, the hardest type of rock found on the entire island. This can only be obtained in one specific place: Rua Toki-Toki, a toki quarry just south of Ovahe on the northern side of Rapa Nui. Its rarity, along with the fact that it was still employed for something as essential and significant as carving Moai statues, made it immensely precious in ancient times.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Easter Island Statues – The Purpose Behind the Moai Statues.” Art in Context. January 13, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/easter-island-statues/

Meyer, I. (2023, 13 January). Easter Island Statues – The Purpose Behind the Moai Statues. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/easter-island-statues/

Meyer, Isabella. “Easter Island Statues – The Purpose Behind the Moai Statues.” Art in Context, January 13, 2023. https://artincontext.org/easter-island-statues/.