Famous Roman Statues – The Best Ancient Roman Sculptures

The Roman Empire is one of the most important empires in history as it spans hundreds of years and over many continents. Traces of this history and influence can be seen in the monuments, statues, and relics that have survived the test of time. The ancient Roman Empire is well-known for its remarkable military might and its commitment to arts and culture. Public sculptures enjoyed especially high priority as they commemorated military victory and served as political propaganda. This article introduces famous Roman statues, including a selection of ancient Roman sculptures and some more recent sculptures by famous Italian artists, such as Michelangelo and Bernini.

Table of Contents

- 1 The History of Roman Sculpture

- 2 Top 15 Famous Roman Statues

- 2.1 The Orator (1st Century BC) by Unknown

- 2.2 Head of a Roman Patrician (1st Century BC) by Unknown

- 2.3 Laocoön and His Sons (Between c. 27 BC and 68 CE) by Agesander, Athenedoros, and Polydorus

- 2.4 Augustus of Prima Porta (1st Century CE) by Unknown

- 2.5 Trajan’s Column (110 CE) by Apollodorus of Damascus

- 2.6 Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius (176 CE) by Unknown

- 2.7 Fonseca Bust (2nd Century CE) by Unknown

- 2.8 The Four Tetrarchs (300 CE) by Unknown

- 2.9 Pietà (1498 – 1499) by Michelangelo

- 2.10 The Tomb of Pope Julius II (Moses) (1505-1545) by Michelangelo

- 2.11 The Rape of Proserpina (1621 – 1622) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

- 2.12 Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647 – 1652) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

- 2.13 Fontana di Trevi (1732 – 1762) by Nicola Salvi

- 2.14 Pauline Bonaparte as Venus Victrix (1805 – 1808) by Antonio Canova

- 2.15 Statue of Giordano Bruno (1889) by Ettore Ferrari

- 3 Book Recommendations

- 3.1 Looking at Greek and Roman Sculpture in Stone: A Guide to Terms, Styles, and Techniques (2003) by Janet Grossman

- 3.2 Roman Portraits: Sculptures in Stone and Bronze in the Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (2016) by Paul Zanker

- 3.3 Naked Statues, Fat Gladiators, and War Elephants: Frequently Asked Questions about the Ancient Greeks and Romans (2021) by Garrett Ryan

- 4 Frequently Asked Questions

The History of Roman Sculpture

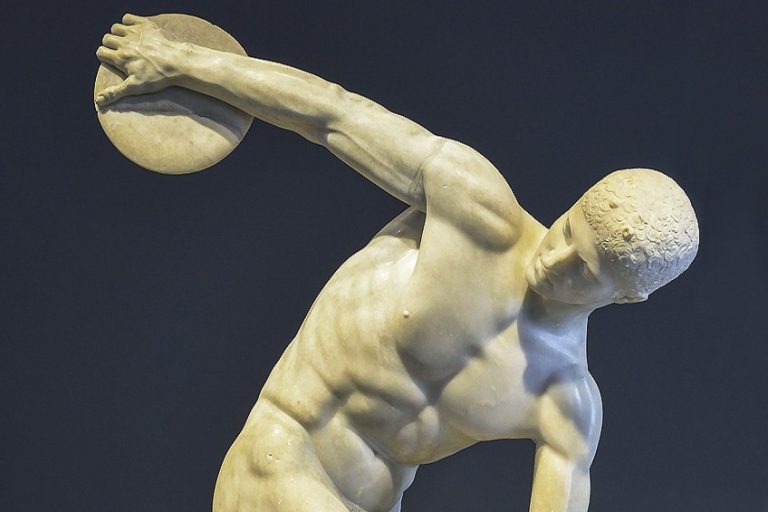

A lot of Roman sculpture characteristics are derived from Greek art. The Roman Empire conquered the Greeks in 146 BC in a battle known as the Battle of Corinth. The Roman elite at the time strived to copy the marble sculptures by famous and skilled artists like Praxiteles, but they were unsuccessful due to the “low-class” status of the Roman artisans. For this reason, many of the Roman statues created during this time were not signed by the artist. Because of this, the Romans preferred the works created by Greek masters.

Interestingly, many of the famous Greek sculptures can today only be seen as Roman reproductions, since the original works were destroyed.

Top 15 Famous Roman Statues

The Romans did, however, make their mark in the history of sculpture, the largest contribution being Rome’s focus on massive public sculptural projects that depicted military victories and complex mythological events. The Roman sculpture also focused greatly on the development of portraiture and the growing interest in verism in their art. Apart from this, famous Roman statues were also created as works of propaganda. This notion can be traced back to Rome’s first emperor, Augustus, who commissioned statues of bronze or marble that idealized the military power of Rome.

Below are a few sculptures that will help us to understand the contribution of Roman statues to the history of art, starting from ancient Roman sculptures and developing into Renaissance and Baroque sculptures.

The Orator (1st Century BC) by Unknown

| Artist | Unknown |

| Artwork Title | The Orator |

| Date | 1st century BC |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Size | 179 cm high |

The Orator (1st century BCE) is a life-size bronze statue. The statue depicts a man named Aule Metele, who was commonly known as “The Orator”. This statue references the origins of the Roman Empire, and it depicts Metele, who was an Etruscan senator in the Roman republic, raising his right arm to a crowd. In the statue, Metele wears a toga exigua, which is a typical outfit of a Roman magistrate. This is significant as Metele is depicted as Roman, even though he is clearly of Etruscan descent and even the names of his Etruscan parents are inscribed into the statue.

This signifies the changing socio-political landscape of Italy at the time and how the Romans dominated other cultures, like how the Roman Empire absorbed the Etruscans, which was a thousand-year-old civilization.

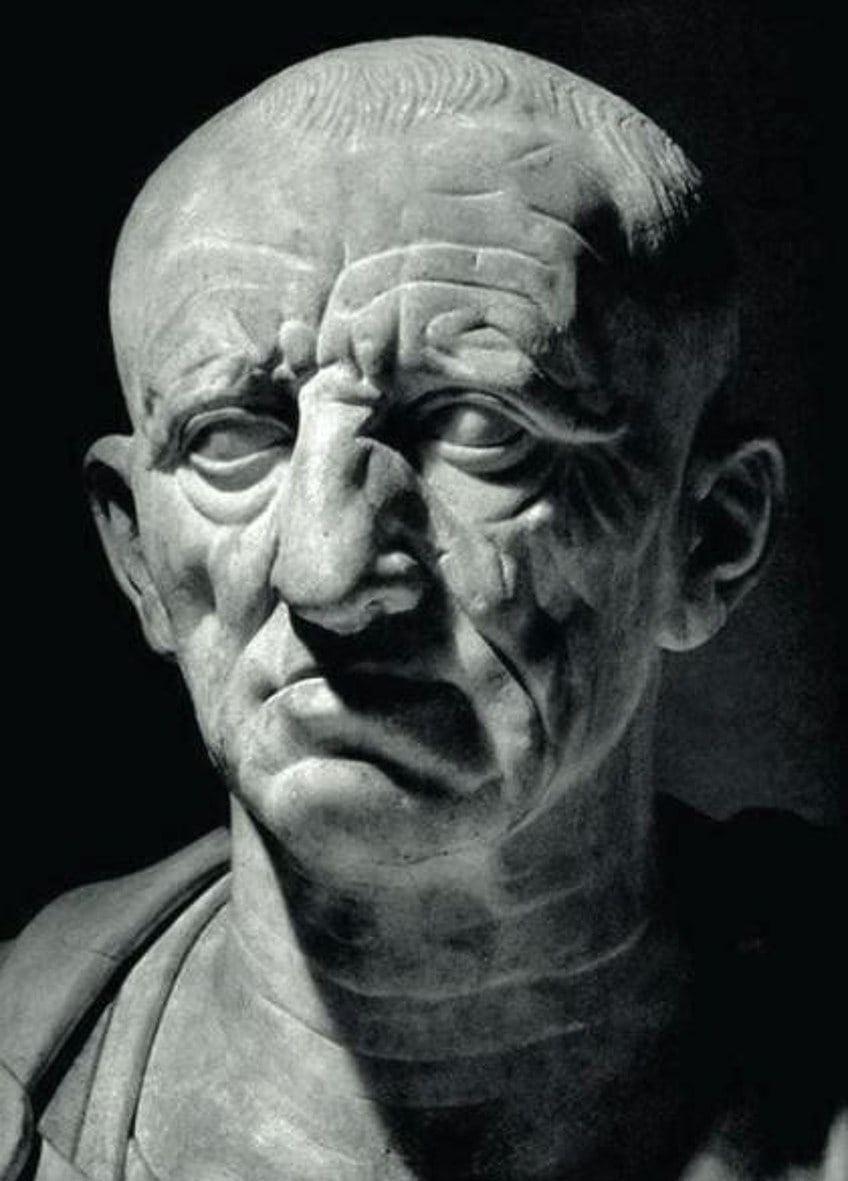

Head of a Roman Patrician (1st Century BC) by Unknown

| Artist | Unknown |

| Artwork Title | Head of a Roman Patrician |

| Date | 1st century BC |

| Medium | Marble |

| Size | Approx. 36cm high |

This sculpture portrays the old and wrinkly face of an unknown Roman aristocrat. The portrait is representative of the seriousness of the mind and the virtue of following a career in public service, and thus it portrays the ideals of the Roman republic. This sculpture is different from those that merely sought to copy Greek statues as it was not an idealized statue of leaders or gods but rather aimed to portray the values of humanity.

For this reason, we do not see the image of a young athletic man, but rather an old man that wears the history of his endeavors on his skin.

The masterful carving of the wrinkled skin represents the wisdom that comes with age. This Roman bust sculpture is currently housed in Rome at the Palazzo Torlonia. This work is a prime example of the Roman veristic style of portraiture that can be described as a kind of hyperrealistic sculpture where the features of a portrait are exaggerated.

Verism was often used in the portrayal of the everyday person, making them appear more distinct or powerful.

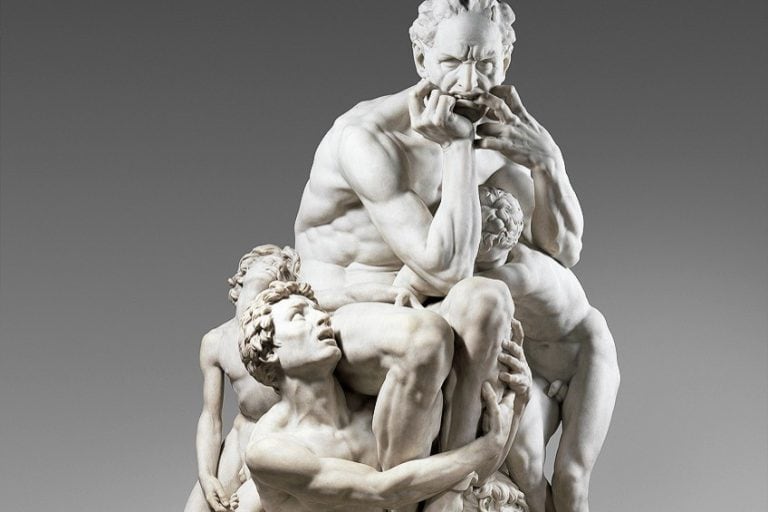

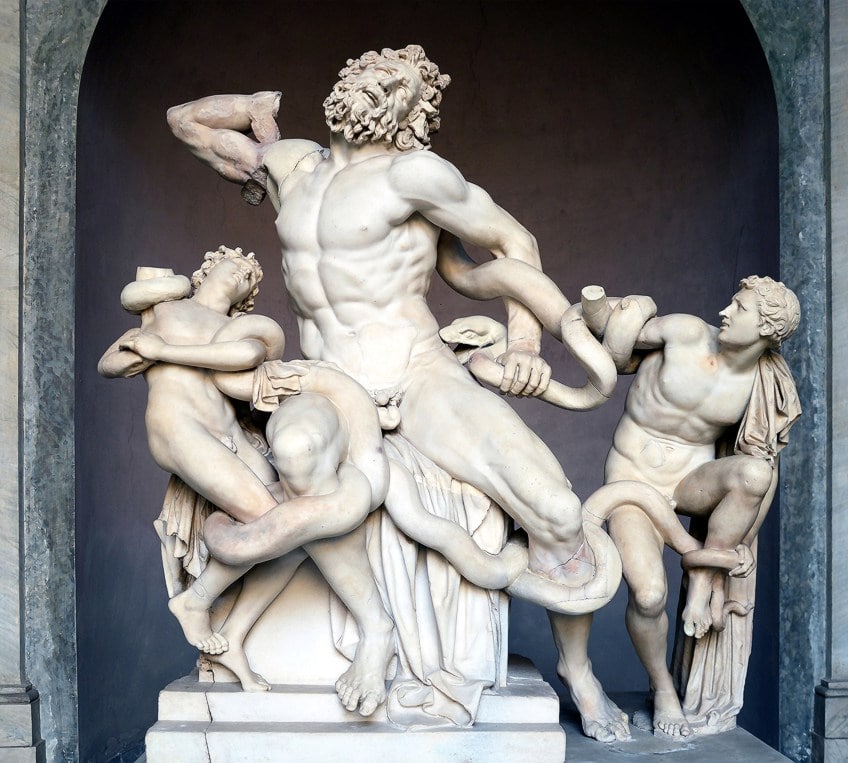

Laocoön and His Sons (Between c. 27 BC and 68 CE) by Agesander, Athenedoros, and Polydorus

| Artist | Agesander, Athenedoros and Polydorus (1st century) |

| Artwork Title | Laocoön and His Sons |

| Date | 72 BC – 68 CE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Size | 208 cm x 163 cm x 112 cm |

In the Museo Pio-Clementino at the Vatican Museum, in the Vatican City, stands the statue Laocoön and His Sons, also called the Laocoön Group. The sculpture was excavated in 1506 in Rome and depicts the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons being attacked by sea serpents.

The most impressive part of the sculpture is the incredible expression of agony that the sculptor managed to capture in marble.

Augustus of Prima Porta (1st Century CE) by Unknown

| Artist | Unknown |

| Artwork Title | Augustus of Prima Porta |

| Date | 1st century CE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Size | 2.03 meters high |

This is one of the most famous portraits of Augustus, the first emperor of Rome. The name of the statue was derived from the town in Italy, Prima Porta, where the statue of Augustus was found in 1863. Augustus was a staunch supporter of public arts and commissioned an estimate of 70 sculptures to be made of him to legitimize his new role as Emperor.

The sculpture is now on display at the Vatican Museum.

This sculpture is cleverly created to depict the power of the emperor and to display his ideologies. In this statue, Augustus is shown as a military hero and a supporter of the Roman religion. The statute features an intricately carved breastplate that illustrates Augustus as a military victor and peacemaker that has the gods on his side. The scenes on the breastplate further allude to Augustus’ link to the past and the golden Roman era.

This sculpture does not contain any verism, as Augustus is displayed as a young, athletic, and powerful idealized figure, similar to those seen in Greek sculptures.

Trajan’s Column (110 CE) by Apollodorus of Damascus

| Artist | Apollodorus of Damascus (1st century-120s) |

| Artwork Title | Trajan’s Column |

| Date | 110 CE |

| Medium | Carrara marble |

| Size | Over 3 meters high |

This work is one of many that was commissioned by Emperor Trajan after he conquered Romania (then called Dacia) in 107 CE. This victory stretched the boundaries of the Roman Empire to its greatest extent. Trajan’s Column is a public column that celebrates the victories of the Roman Empire and especially the Dacian wars fought during Emperor Trajan’s reign. After Trajan’s substantial victory, he announced 100 days of celebrations.

The column also served as Trajan’s tomb.

The column is illustrated with the events of the wars, carved into the column in a continuous spiral frieze. These illustrations contain over 2000 relief figures of soldiers and Trajan himself is illustrated 58 times. While the column has been studied by archaeologists to understand the events of the wars, it is mostly believed that the events carved into the column were designed as propaganda and it is likely that it is embellished and not factual.

The column still stands in the Forum of Trajan in Rome, where it was originally constructed.

Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius (176 CE) by Unknown

| Artist | Unknown |

| Artwork Title | Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius |

| Date | 176 CE |

| Medium | Gilded bronze |

| Size | Approx. 4.24 meters high |

This massive bronze Roman statue has served as a model for equestrian sculpture throughout European art history. Equestrian statues were common in ancient Rome, but today there exist few examples from antiquity, making the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius a particularly impressive and important artistic artifact in all of art history. Many such statues were destroyed by the Catholic Church during the Middle Ages, but it is believed that this statue was saved because it was wrongly believed to be representing the Christian emperor of Rome, Constantine.

This gilded bronze statue was, however, initially dedicated to emperor Marcus Aurelius during the 170s CE.

The statue is much larger than life-size, and its imposing presence is a powerful depiction of the emperor in motion, raising his right arm while his horse’s right foreleg is also raised. The depiction of movement in the sculpting of the horse is an excellent example of the dynamism that existed in Roman sculpture.

The outstretched hand of the horsemen, with his palm facing the ground, is believed by some to be a pose that was called adlocutio, which indicated that the emperor was about to speak. Others believed that the pose is that of the gesture of clemency that was shown to a defeated enemy. Some believe that the pose is that of restitutio pacis, which means that peace is restored.

Regardless of the meaning, the pose is political, and the masculine depiction of the emperor showcases his power and authority.

From the 8th century, the statue stood at the Lateral Palace in Rome, but it was moved to the Piazza del Campidoglio in 1538. Here, Michelangelo worked on the statue’s refurbishment. In 1981 the statue was moved again to the Palazzo dei Conservatori where it still stands today. Here, the statue is held for preservation and safekeeping.

A copy of the statue stands in the Piazza del Campidoglio, on the top of Capitoline Hill.

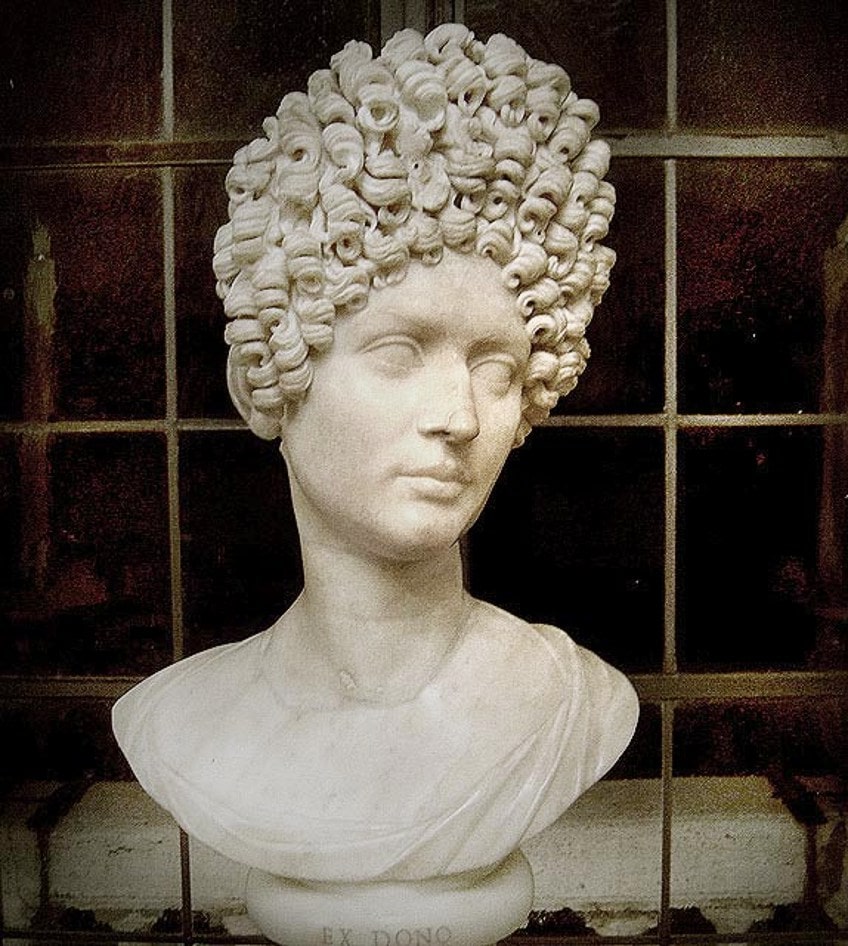

Fonseca Bust (2nd Century CE) by Unknown

| Artist | Unknown |

| Artwork Title | Fonseca Bust |

| Date | 2nd century CE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Size | 63 cm high |

The Fonseca Bust is one of few female Roman statues dated to the beginning of the 2nd-century CE. The Roman bust sculpture is of an elite Roman woman that is believed to be of the Flavian dynasty (69 – 96 CE).

Female Roman statues were typically portrayed with less detail and their portraits were often less realistic and more general.

The reason for this was that sculptures of women were typically commissioned to showcase both general female beauty and the fashions of the time. This woman especially would have been of the most fashionable and elite at the time due to her elaborate hairstyle.

The elaborate curls piled on the head of the woman would most likely have been created by a hairstylist that sewed in extensions to the woman’s natural hair. This was something that only the wealthiest could do at the time. The portrait not only showcases the beauty and fashion of Roman women, but also the skill of the artist in the creation of the incredibly detailed carving of the hairstyle.

This sculpture is currently housed at the Musei Capitolini in Rome.

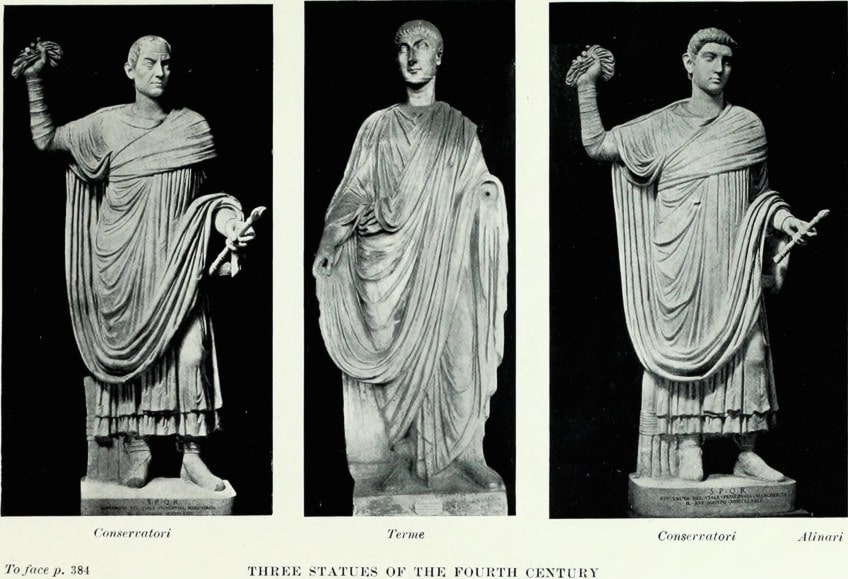

The Four Tetrarchs (300 CE) by Unknown

| Artist | Unknown |

| Artwork Title | The Four Tetrarchs |

| Date | 300 CE |

| Medium | Porphyry |

| Size | 129 cm high |

The Four Tetrarchs is a sculpture made from porphyry, a rare Egyptian rock with a regal red-purple hue. The sculpture stands in a corner of the Piazza San Marco, and it is often overlooked by tourists. The style, subject matter, and material are however not something to be overlooked at all.

Symbolizing the imperial power of Rome, the rare porphyry stone memorializes an interesting period in Roman politics.

The statue portrays the Tetrarchy, a unique governmental system created by Emperor Diocletian. This government was created to end the foreign invasions and civil wars that plagued Rome for years. The Roman Empire had gotten so large that one man alone could not rule it. Emperor Diocletian decided to create the “rule of four” by dividing the empire in two and by appointing an emperor and vice-emperor for each half.

The statue did not, however, always stand in Italy.

The Four Tetrarchs originally stood in Constantinople for approximately 1000 years. The statue was stolen in the 13th-century by the Venetians when they invaded the city during the Fourth Crusade. When the statue was taken from its original spot, a part of the foot of the sculpture accidentally broke off. This foot was lost until the 1960s when it was discovered in Istanbul by archaeologists. This missing foot can still be seen in Istanbul.

Pietà (1498 – 1499) by Michelangelo

| Artist | Michelangelo (1475-1564) |

| Artwork Title | Pietà |

| Date | 1498 – 1499 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Size | 1.74 m x 1.95 m |

The Pietà is not of the ancient Roman sculptures, as discussed in the examples above, but rather a Renaissance sculpture by the famous Michelangelo Buonarotti. This is arguably one of the most famous Roman sculptures and it can be seen in St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican City. The sculpture is right at home in the Basilica with its strong Christian theme of the mother Mary cradling the body of Christ after the Crucifixion.

Interestingly, this is the only work that Michelangelo ever signed.

The Tomb of Pope Julius II (Moses) (1505-1545) by Michelangelo

| Artist | Michelangelo (1475-1564) |

| Artwork Title | The Tomb of Pope Julius II (Moses) |

| Date | 1505 -1545 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Size | 254 cm high |

The Tomb of Pope Julius II (Moses) is another well-known work of Michelangelo and most people refer to the work as The Horned Moses or Michelangelo’s Moses. The work was commissioned in 1505, but it was not actually completed until 1545 when the pope passed away. The work was originally to be housed in St. Peter’s Basilica, but was instead placed in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli after the pope’s death.

The final sculpture was made at a much-reduced scale compared to its original design.

Michelangelo was severely disappointed as the scale of the commission was reduced by the pope, possibly due to budget constraints, as the original design was to consist of a free-standing three lever sculpture with approximately 40 statues. Regardless of his disappointment, Michelangelo believed that his Moses was the realistic work he created in his lifetime.

The Rape of Proserpina (1621 – 1622) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

| Artist | Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) |

| Artwork Title | The Rape of Proserpina |

| Date | 1621 – 1622 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Size | 174 cm x 195 cm |

The Rape of Proserpina is a work created by the famous Baroque Italian sculptor, Gian Lorenzo Bernini at the young age of 23 years old. The work depicts the abduction of Proserpina, who was an ancient Roman mythological goddess of wine. In the sculpture, Proserpina is taken by the god Pluto to join him in the underworld.

According to the traditional Latin translation, the word “rape” did not necessarily mean sexual violence, but rather to seize, capture, or carry off.

The work was commissioned by Cardinal Scipoine Borghese and today it can be seen in the Galleria Borghese in Rome. The work is exceptional in its sensual and delicate portrayal of the human form, expression, and movement.

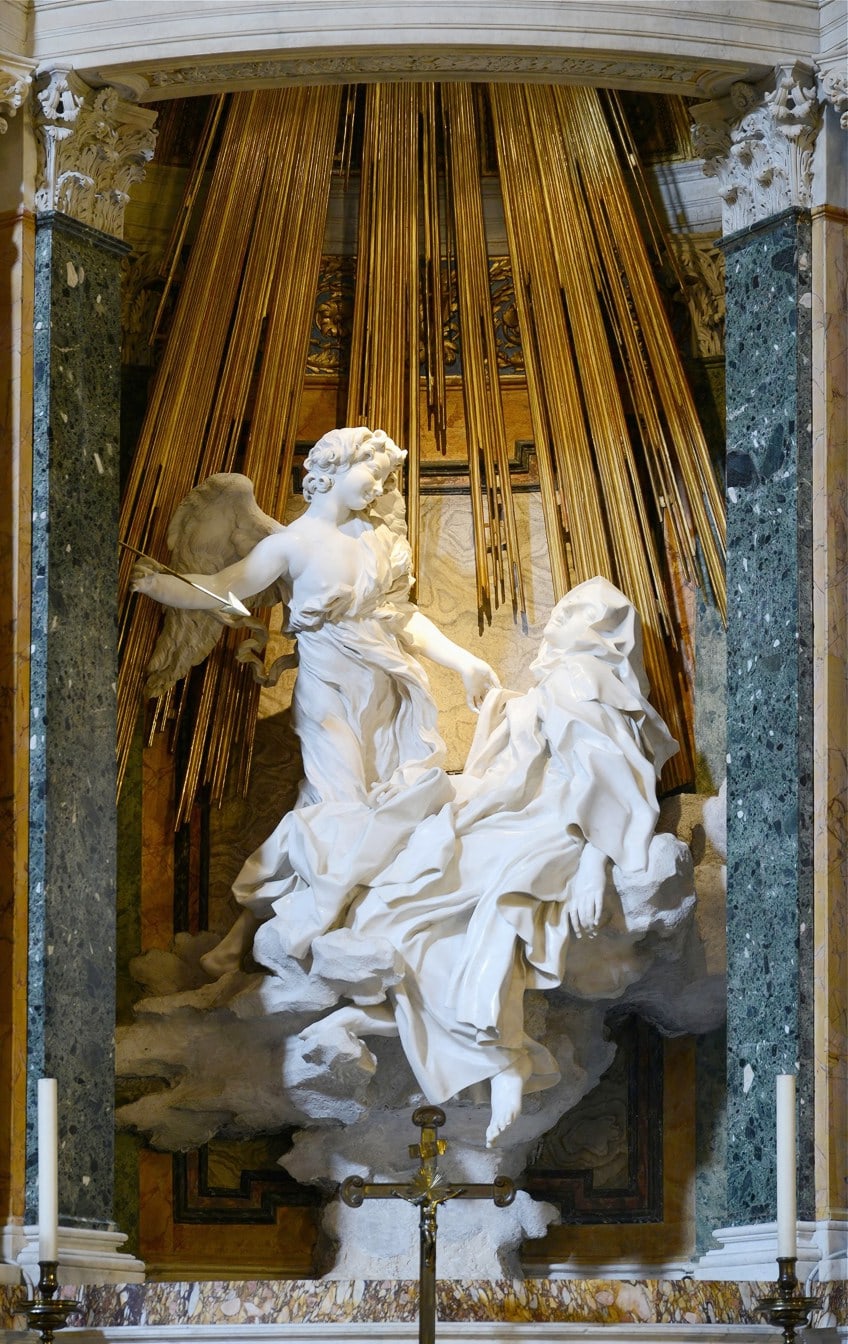

Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647 – 1652) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

| Artist | Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) |

| Artwork Title | Ecstasy of Saint Teresa |

| Date | 1647 – 1652 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Size | 174 cm x 195 cm |

The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa is another work created by Baroque sculptor Bernini, and it can be found in the Cornaro Chapel of the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome. The chapel itself is also designed by Bernini and is considered to be one of the greatest masterpieces of the Roman Baroque era.

The “Ecstasy of Saint Teresa”, which is also known as the “Transverberation of Saint Teresa”, is a sensual and detailed sculpture that depicts Saint Teresa of Ávila, a Spanish Carmelite nun, in a moment of religious ecstasy while an angel above, carrying a spear, hovers above her.

Fontana di Trevi (1732 – 1762) by Nicola Salvi

| Artist | Nicola Salvi (1697-1751) |

| Artwork Title | Fontana di Trevi |

| Date | 1732 – 1762 |

| Medium | Travertine stone |

| Size | 26.3 m x 49 m |

The Fontana di Trevi, also called the Trevi Fountain is a must-visit for any movie lover as it features in films including Roman Holiday (1953), Three Coins in the Fountain (1954), La Dolce Vita (1960), Sabrina Goes to Rome (1998), The Lizzie McGuire Movie (2003), and When in Rome (2010).

The fountain is one of the most famous fountains in the world and it is the largest Baroque fountain in Rome.

Pauline Bonaparte as Venus Victrix (1805 – 1808) by Antonio Canova

| Artist | Antonio Canova (1757-1822) |

| Artwork Title | Pauline Bonaparte as Venus Victrix |

| Date | 1805 – 1808 |

| Medium | Carrara Marble |

| Size | 160 cm high |

The famous Italian Neoclassical sculptor, Antonio Canova, was commissioned to create this iconic sculpture in 1804 by Prince Camillo Borghese. The sculpture is of the prince’s wife, Pauline Bonaparte, who was the sister of Napoleon.

Though the marriage between Bonaparte and Borghese was not a particularly happy one, the prince nonetheless wanted to have an immortalized portrait of his beautiful and royal wife.

Bonaparte is portrayed as Venus in this sculpture, holding an apple to indicate that she is the most beautiful of all the goddesses. Many rumors were circulating at the time accusing Bonaparte of posing in the nude for the artist, and she herself is recorded saying that “all veils may fall before Canova”.

Statue of Giordano Bruno (1889) by Ettore Ferrari

| Artist | Ettore Ferrari (1845-1929) |

| Artwork Title | Statue of Giordano Bruno |

| Date | 1889 |

| Medium | Bronze |

This ominous statue of a hooded figure was erected in the memory of the execution of the radical politician Giordiano Bruno. Bruno was sentenced to burn at the stake in the year 1600 for hearsay. At the base of the sculpture, an inscription reads “To Bruno – From the Age He Predicted – Here Where the Fire Burned”.

The initial plan was that the statue should face the sun, but the artist decided to face the sculpture to the North instead, facing the Vatican.

This decision meant that the face of the figure would be perpetually shaded by its hood, making the work even more melancholy. Today, the statue marks the ideals of freedom of opinion and speech. Every year on the 17th of February, the anniversary of Bruno’s execution, various groups of freethinkers place wreaths onto the feet of the sculpture.

The statue can be seen in the Piazza Campo de’ Fiori.

Book Recommendations

The vastness of Roman statues is impossible to capture in one small article. For this reason, we looked at some book recommendations for you to explore statues and sculptures from this era further. These books do not necessarily discuss the statutes named in this article, but rather focus on where you can read on from this point forward.

Looking at Greek and Roman Sculpture in Stone: A Guide to Terms, Styles, and Techniques (2003) by Janet Grossman

This book explains some of the difficult and strange terminologies that often get used when discussing ancient Roman or Greek sculpture. Whether you want to understand these terms when going on a tour or explain interesting facts to friends and family, this book is a good choice to set your way. Some of the terms include “Cycladic”, “kouroi, “tool marks”, “joins”, kanephoroi” and “Daedalic styles”. The book also serves as a go-to guide and includes a glossary of terms, paired with concise and clear definitions, and remarkable illustrations.

- A superbly illustrated book presented in glossary format

- Explains words and phrases often encountered in museums

- Features numerous illustrations of ancient stone sculptures

Roman Portraits: Sculptures in Stone and Bronze in the Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (2016) by Paul Zanker

This well-illustrated book takes a closer look at portraiture in Greek and Roman sculpture. The book looks closely at 60 portraits examples and places them within the cultural and historical context within which they were created. This is an excellent book to gain a deep understanding of why these works of art are so remarkable.

- A richly illustrated book featuring all-new photography

- A multifaceted survey of Roman stone and bronze portraiture

- Includes a brief overview of the history of ancient portraiture

Naked Statues, Fat Gladiators, and War Elephants: Frequently Asked Questions about the Ancient Greeks and Romans (2021) by Garrett Ryan

This is a comedic and enjoyable book that answers interesting questions about the Greeks and Romans. Garret Ryan is an ancient historian, and his humorous essays will be sure to delight and educate. This is a lovely introduction to the fascinating and strange aspects of Greek and Roman life, and while it might not directly be about sculptures and statues, it will give you great insight into the mindsets and eras in which the statues were made.

- A series of short and humorous essays

- Explores questions about the Greeks and Romans

- With a focus on the fascinating details of daily life

Romans were greatly inspired by Greek sculpture. At first, their attempt was simply to copy the Greek style, but later, Roman sculpture developed into a direction that became unique to them at the time. While Greek sculptures were greatly idealized and often showed youth and exaggerated beauty, the Roman sculpture was more realistic. Roman statues and sculptures influenced art history on a massive scale and helped shape our ideas about the function and boundaries of art, and how to cross those boundaries and take it even further.

Take a look at our Roman statues webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Most Famous Roman Sculpture?

It is very difficult to pin down one specific Roman sculpture or statue as the most famous. There is a long history and huge collection of incredibly famous Roman sculptures, many of which are greatly admired equally by many. Some of the most famous Roman sculptures might include the Statue of Julius Caesar at the Via dei Fori Imperiali, Trajan’s Column at the Piazza Venezia, or the Sculptures of Ara Pacis at the Piazza Augusto Imperatore

What Are the Major Types of Roman Sculptures?

Roman sculpture characteristics can broadly be categorized into three main types. These types are statues, busts, and architecture. Busts often focus more on the portraiture of sculpture, whereas statues focus more on the portrayal of important events and people, mythologies, or gods. Architecture from these eras was often sculpturally embellished with a relief sculpture that tells of military feats or events. The architectural styles of different periods can in themselves be a form of sculpture giving insight into the sociopolitical landscape of the time.

What Do Roman Statues Represent?

Roman sculpture often served a purpose. Some of the reasons why Roman statues were created was to honor and memorialize important figures in their society and culture. Roman statues thus often include portrayals of emperors, mythological gods, military generals, and leaders.

Chrisél Attewell (b. 1994) is a multidisciplinary artist from South Africa. Her work is research-driven and experimental. Inspired by current socio-ecological concerns, Attewell’s work explores the nuances in people’s connection to the Earth, to other species, and to each other. She works with various mediums, including installation, sculpture, photography, and painting, and prefers natural materials, such as hemp canvas, oil paint, glass, clay, and stone.

She received her BAFA (Fine Arts, Cum Laude) from the University of Pretoria in 2016 and is currently pursuing her MA in Visual Arts at the University of Johannesburg. Her work has been represented locally and internationally in numerous exhibitions, residencies, and art fairs. Attewell was selected as a Sasol New Signatures finalist (2016, 2017) and a Top 100 finalist for the ABSA L’Atelier (2018). Attewell was selected as a 2018 recipient of the Young Female Residency Award, founded by Benon Lutaaya.

Her work was showcased at the 2019 and 2022 Contemporary Istanbul with Berman Contemporary and her latest solo exhibition, titled Sociogenesis: Resilience under Fire, curated by Els van Mourik, was exhibited in 2020 at Berman Contemporary in Johannesburg. Attewell also exhibited at the main section of the 2022 Investec Cape Town Art Fair.

Learn more about Chrisél Attwell and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Chrisél, Attewell, “Famous Roman Statues – The Best Ancient Roman Sculptures.” Art in Context. July 21, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/famous-roman-statues/

Attewell, C. (2022, 21 July). Famous Roman Statues – The Best Ancient Roman Sculptures. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/famous-roman-statues/

Attewell, Chrisél. “Famous Roman Statues – The Best Ancient Roman Sculptures.” Art in Context, July 21, 2022. https://artincontext.org/famous-roman-statues/.