The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living

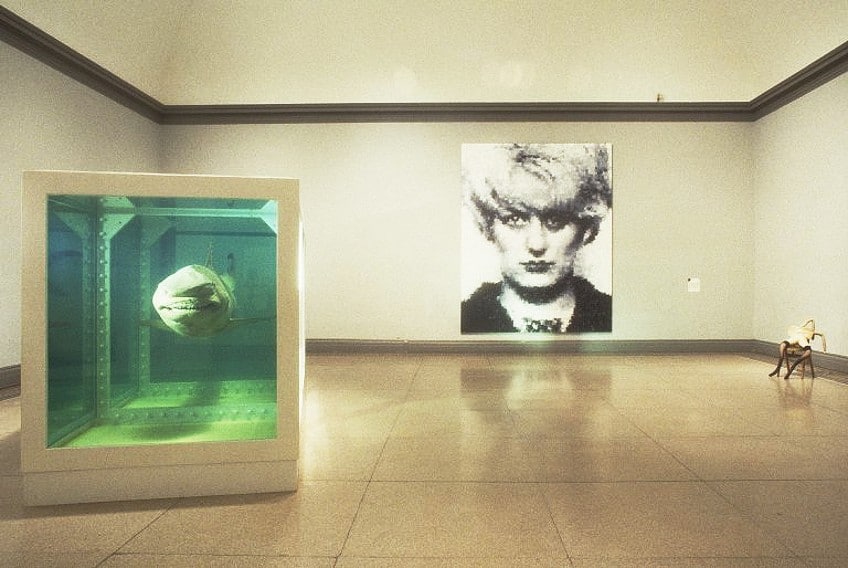

The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, by Damien Hirst, also known as The Shark, was created in 1991. Charles Saatchi commissioned this shark-in-formaldehyde artwork and then subsequently sold it to Steven A. Cohen in 2004. The first tiger shark was substituted with a replacement specimen in 2006 due to degradation.

Table of Contents

The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) by Damien Hirst

Hirst’s diverse creative approach is based on historical precedents of Marcel Duchamp’s readymade assemblages, and Concept Art of the 1970s. The artist’s career rose quicker than that of his friends from the Young British Artists period, and he became well-known for contentious hybrid pieces characterized by themes like skulls, and creatures suspended in formaldehyde.

Damien Hirst’s early work laid the groundwork for his future success and critical praise.

An Introduction to Damien Hirst

| Nationality | English |

| Date of Birth | 7 June 1965 |

| Date of Death | N/A |

| Place of Birth | Bristol, United Kingdom |

Damien Hirst’s practice encompasses installations, sculptures, painting, and sketching. His visceral, aesthetically captivating work, which consistently challenges the borders between science, art, and religion, has established him as a major artist of his generation. Hirst explores the tensions and ambiguities that lie at the core of human experiences. Passion, ambition, belief, and the difficulties of living with the awareness of mortality are all explored, often in surprising and uncommon ways.

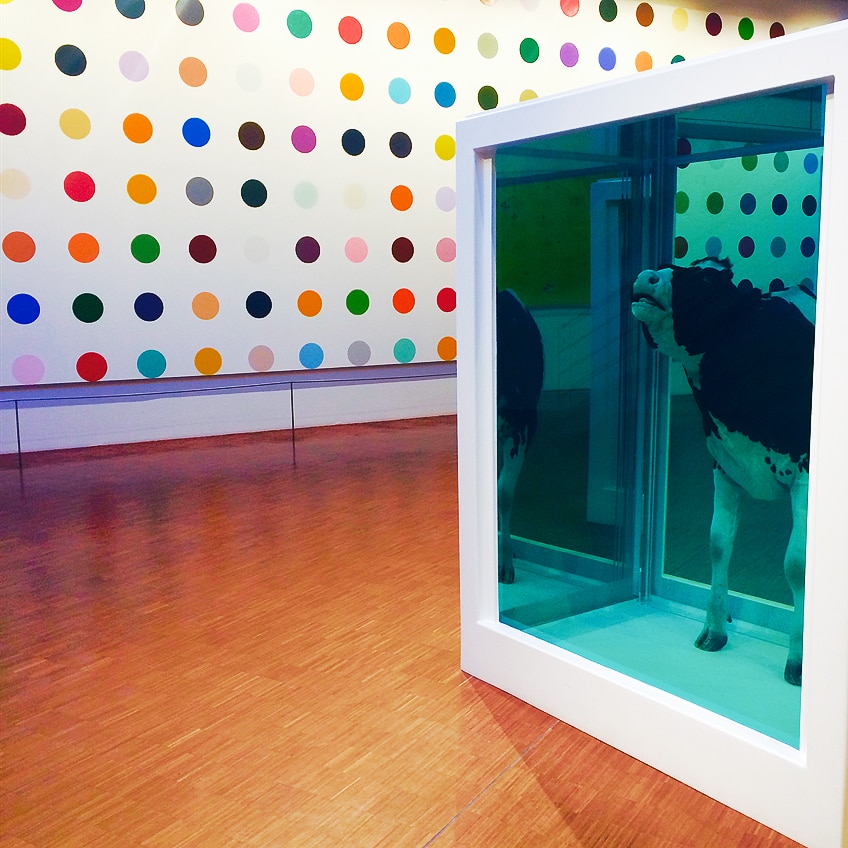

Damien Hirst is arguably most known for his ‘Natural History’ series of sculptures, which depict creatures immobilized in formaldehyde in vitrines.

The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991), for example, aims to reframe basic problems about the nature of existence and the frailty of physiological existence. Hirst uses display cases as both a portal and a barrier, visually captivating the observer while also giving a simple geometry to enclose, confine, and objectify his material.

In his iconic piece A Thousand Years (1990), he initially built a glass and steel container in which flies emerge, consume, and die as a result of an insect-O-cutor, creating a tiny life cycle. Several of his other sculptures from the 1990s include relic-like artifacts such as cigarettes, garments, trays, chairs, and tables, implying a human presence via their absence.

One of Hirst’s most lasting themes is science and our unwavering confidence in the power of drugs.

These concepts are explored in the exhibition Pharmacy (1992) as well as the Medicine Cabinets, which showcase a plethora of reflecting, precision-tooled surgical equipment within glass and steel displays. Other works have a more joyful tone, such as Hymn (2001), a polychrome bronze sculpture that shows the human body’s muscles and vital organs in toy-like anatomical representations magnified to a mammoth size.

Hirst is also recognized for his paintings, such as the “Kaleidoscope Paintings”.

These include hundreds of butterfly wings organized in mandala-like patterns. The accompanying ‘Entomology Cabinets’ use the same elements but arrange them in exact vertical and horizontal rows within minimalist and shiny stainless-steel wall-mounted casings.

The Shark in Formaldehyde Artwork

| Date Completed | 1991 |

| Medium | Shark in formaldehyde |

| Dimensions | 213 cm × 518 cm × 213 cm |

| Location | Tate Modern |

The fact that the animal has been stripped from its natural environment means that it is still, fixed, and preserved, which is what makes this thing so strange and astounding. Many people have only seen sharks on tv or in aquariums, therefore the piece effectively lets the audience view it in a safe environment and maybe address their abstracted anxieties.

In particular, this work raises the dilemma of how we communicate with nature and other organisms, and the artist primarily acts as a mediator of experience.

This allows the work to operate on several levels, including psychologically with human fears, zoologically with an animal’s qualities and attributes, culturally with the troubling imagery, and finally artistically with the widening of the artistic canon.

Concept and Background

Charles Saatchi, who in 1991 pledged to pay for whatever artwork Hirst desired to produce, provided the funding for the piece. A fisherman hired to complete the job captured the shark near Hervey Bay in Queensland, Australia. Something “large enough to devour you” was what Hirst desired.

It was initially displayed in 1992 as part of the Saatchi Gallery’s first in a succession of Young British Artists exhibitions, which took place at the gallery’s location in St. John’s Wood in England.

A Thousand Years, another piece of art by Hirst, was on display. He was then put forward for the Turner Prize, but Grenville Davey ended up winning it. Steven A. Cohen was given the piece by Saatchi. The artwork was described in the following way by

The New York Times in 2007: “Mr. Hirst frequently attempts to sear the mind (and fails more often than he succeeds), but he does it by creating immediate, frequently visceral sensations, among which the shark continues to stand out as the most notable. In line with the piece’s name, the shark represents both life and death in a way that is difficult to understand until you see it in its tank, poised and silent. It lends a diabolical, deathlike shape to the essentially evil need to survive”

Deterioration and Substitution

The shark’s original preservation was inadequate, so it started to decay and the liquid around it turned murky. Hirst ascribed a portion of the degradation to the Saatchi Gallery’s use of bleaching agents in the fluid.

The gallery gutted the shark in 1993 and wrapped its skin over a fiberglass mold, turning it from an entire carcass that had been chemically preserved into a taxidermy mount that was being presented in motion.

Hirst remarked, “It didn’t appear to be as terrifying. It was fake, that much was clear. It was weightless.” Damien Hirst volunteered to replace the shark after he heard that Saatchi would be selling the piece to Cohen. Cohen agreed to pay for the replacement, calling the cost “immaterial” (the formaldehyde procedure alone cost over $100.000).

The second shark, a female, was taken off the coast of Queensland and transported over a two-month period to Hirst. She was around 25 years of age or middle age. The new specimen’s preservation was helped in 2006 by Oliver Crimmen, a biologist and marine conservator at the Natural History Museum in London. This required pumping formaldehyde into the organism and bathing it in a 7-percent formalin solution for two weeks. Then it was kept in the original 1991 vitrine.

Hirst noted that it was debatable from a philosophical standpoint whether the artwork would still be the same if the shark had been removed. “It’s a serious conundrum”, he said about the work.

Regarding whether the original piece or the original aim is more significant, artists and conservators have contrasting views. Since my background is in conceptual art, I believe that this should be the goal. The item is identical. However, the verdict won’t be known for some time to come.

Response

Under the caption A Dead Shark Isn’t Art, the Stuckism International Gallery displayed a shark in 2003 that Eddie Saunders had initially shown in front of the public in his London store two years earlier. The Stuckists hypothesized that Saunders’ store displays may have given Hirst the inspiration for his artwork.

Robert Hughes, an art critic, described “The Shark” as a prominent illustration of the worldwide art market at the time being a “cultural obscenity” in a speech he gave at the Royal Academy in 2004.

He said that brush strokes in a Velázquez painting’s lace collar may be more revolutionary than a shark “murkily dissolving in its tank on the opposite side of the Thames,” without mentioning the piece of art or the artist. Additionally, some have questioned the morality of the portion of Hirst’s body of work that features deceased animals. One estimate places the total number of animals and insects killed for one of Hirst’s works at 913,450. Director Andrei Konchalovsky describes a moment in the 2009 British-Hungarian movie The Nutcracker when a pet shark is electrified in a water tank as a nod to Hirst’s work.

“But you didn’t, did you”, Hirst remarked in response to critics who claimed that anybody could have created this piece of art. The Shark is unquestionably praised as one of the key pieces of British art from the 1990s and has come to represent Britart across the world. It is obvious from a modern viewpoint that it altered the direction of 20th-century art and expanded its limits, raising important concerns about interspecies interaction, marine biodiversity, and human anxieties, regardless of whether we may argue that it is terrible or excellent art or whether it is even art.

Damien Hirst has consistently pushed the limits of what is considered to be art, science, the media, and popular culture.

Hirst uses a variety of mediums to convey his unwavering view of the ambiguity at the core of the human experience, including a 12-foot tiger shark, a cow, and her calf sawn in half, drug store containers, residential paint pumped onto rotating canvases, cig butts, cabinetry, office equipment, surgical equipment, insects and tropical fish, and most lately, a diamond-encrusted skull.

How do we interpret “The Shark”, then? It is entirely cut off from its surrounding environment. In the water, where it would normally be in motion, it is fully frozen and preserved. Given that many of us have only ever seen sharks in aquariums or on television, for the majority of us, this may be the first time we have been this close to one. Here, the shark is experienced directly, unmediated by any media. As a result, we are compelled to reconsider the shark from a new perspective and reconsider how we view the animal. In Hirst’s work, we are compelled to confront the materiality and realism of this well-known picture and to think about it in a different context.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991)?

The sculpture, produced by Damien Hirst in 1991, features a tiger shark maintained and perfectly preserved in a solution of formaldehyde in a glass cabinet. Because the tiger shark was initially inadequately maintained, it started to decay over time and the liquid around it became murky. Damien Hirst says that the Saatchi Gallery applied bleach to it, which contributed to part of the degradation. The shark was gutted and its skin was stretched over a fiberglass cast in 1993 by the gallery.

Where Did the Second Shark Come From?

A second shark was captured off Queensland and transported to Hirst during a two-month period. In 2006, the Natural History Museum in London contributed to the conservation of the new species. In order to do this, the shark’s body was filled with formaldehyde and bathed in a formalin solution.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living.” Art in Context. July 6, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/the-physical-impossibility-of-death-in-the-mind-of-someone-living/

Meyer, I. (2022, 6 July). The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/the-physical-impossibility-of-death-in-the-mind-of-someone-living/

Meyer, Isabella. “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living.” Art in Context, July 6, 2022. https://artincontext.org/the-physical-impossibility-of-death-in-the-mind-of-someone-living/.