“Venus of Willendorf” – Figurative Sculpture from the Paleolithic

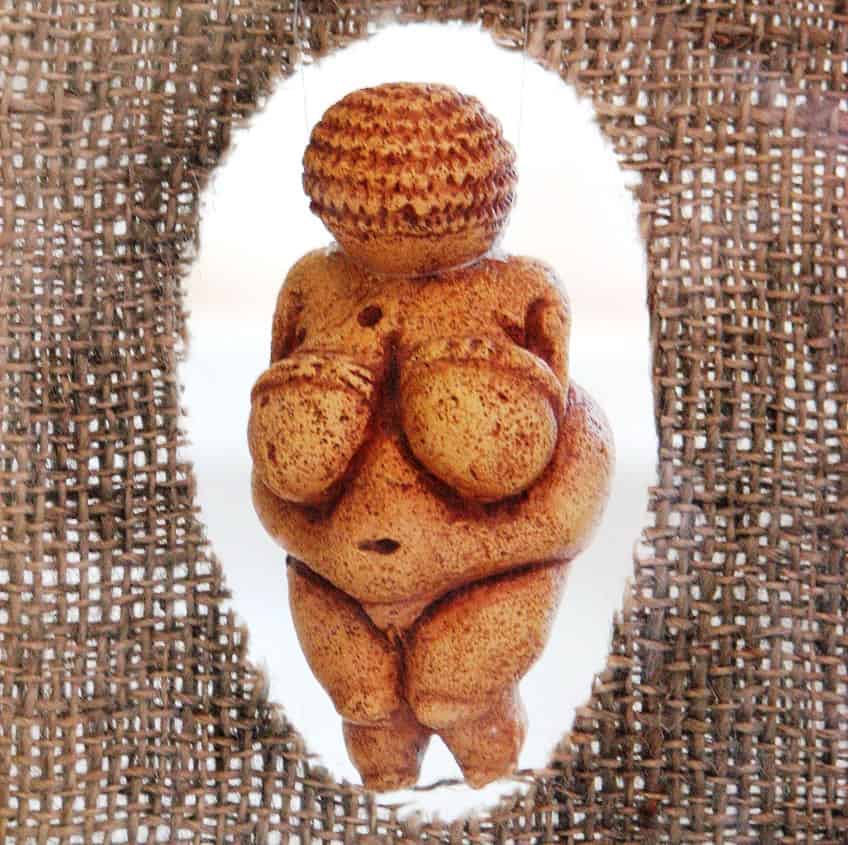

The Venus of Willendorf, also called Woman of Willendorf or Nude Woman, is a female figurine found in 1908 at Willendorf, Austria. The fertility goddess statue is considered a piece of Upper Paleolithic art, carved out of oolitic limestone. The Venus of Willendorf statuette can today be viewed in Vienna’s Natural History Museum. This piece of prehistoric art opens a discussion on Neolithic women; what were they revered for, what was expected of them, and how does the Woman of Willendorf portray these characteristics? This Venus of Willendorf analysis will attempt to bring light to these questions.

Table of Contents

The Venus of Willendorf Statue

| Title | Venus of Willendorf (Also known as the Woman of Willendorf or Nude Woman) |

| Date Created | 24,000 – 22,000 B.C.E. |

| Medium | Oolitic limestone |

| Dimensions (cm) | 11.1 |

| Current Location | Natural History Museum, Vienna. |

| Value | Unknown |

The Venus of Willendorf is a piece of Upper Paleolithic art, at 11.1 centimeters (4.4 inches) tall, estimated to have been created around 28,000-25,000 BC. The figurine was made from oolitic limestone and tinted with red ochre pigment.

It was found near Willendorf, Austria at a Paleolithic site on the 7th of August in 1908 by Johann Veran or Josef Veram, from excavations conducted by archaeologists Josef Szombathy, Hugo Obermaier, and Josef Bayer.

Upon its discovery, archaeologists initially estimated that the sculpture was from around 10,000 BC, although further findings dated the fertility goddess statue at 20, 000 years old by the 1970s, with the conclusive finding dating the statue to between 25,000 and 30,000 BC following an analysis of the rock layers in 1990.

The Venus has been classified as part of the upper Paleolithic Gravettian industry, which refers to around 33,000 to 20,000 years ago, with the figurine said to have been left in the ground around 25,000 years ago, an estimate found by archaeologists based on the radiocarbon dates from the layers in the ground surrounding the piece.

The origins of the oolitic limestone can be traced back to the other side of the Alps, near Lake Garda in Northern Italy, based on research published in 2022. Archaeologists have also stated that the material could also come from a site in Eastern Ukraine.

Given its small size, the piece was easily transportable. Given the fact that the material it was made from was not indigenous to Austria, archaeologists have found that the piece was made somewhere else before being transported to Willendorf.

The piece is one of about 40 similar pieces, all found nearly to completely intact, mostly depicting female figures, that were found by the early 21st century.

This piece of prehistoric art is also one of many Venus figurines that survived from the Paleolithic era of Europe, with around 80 more figures found in various fragmented pieces, or partial forms. The figure can now be viewed in Vienna, Austria at the Natural History Museum.

Meanings and Interpretations

The Venus of Willendorf was identified as a piece of Upper Paleolithic art, dating from 28,000 to 25,000 BC. Being a piece of prehistoric art, the statuette has been the subject of many different theories and interpretations. When discussing the significance or intentions behind a piece from a previous age, it is essential to understand the historical context of the society or community in which the piece was created.

Historical Context

Given the figure’s prehistoric origins, not much is known about the piece’s context, how it was created, or its intended message and cultural significance. It has, however, been suggested that the piece is meant to be a fertility figure, a symbol of a mother goddess, or a token of good luck.

The term “Venus” comes from the Roman goddess of love, beauty, sex, and fertility. Also known as Aphrodite from Ancient Greek Mythology, Venus was an important figure in Ancient Roman culture, often depicted in art. While the most famous statue depicting the love goddess would be Alexandros of Antioch’s Venus de Milo, which dates from between 150 to 125 BC, the Venus of Willendorf can then be considered the oldest Venus statue, predating Greco-Roman mythology itself by over 20 millennia.

As this figurine, as well as several other pieces with the same title, predates Greco-Roman mythology, the reference to the Roman goddess is metaphorical; based more on what abstract concepts the piece is meant to represent rather than on who it is meant to represent.

As such, the piece of Paleolithic art was given the title of Venus retroactively; named so based on the assertion that the piece was meant to be representative of a symbol of fertility or a fertility goddess. This is likely due to the parts of the figure’s body that are usually associated with childbearing and fertility, such as the prominent breasts, the large hips, and rounded stomach, having been emphasized, even exaggerated.

These features can be found in many similar pieces of prehistoric art, with most of the 144 fertility-related figurines that were found in Europe and Asia sharing these characteristics. During prehistoric times, specifically the Stone Age, these features were linked to a woman’s motherhood and her ability to conceive, which is what they were valued for at the time.

This is why so many prehistoric sculptures depict the Venus figure.

Like the other sculptures found in the area, and from generally the same time period, the Venus of Willendorf was found without feet, with historians believing it never had feet at all and would have been pegged into the ground rather than standing on its own. There is no distinguishable face on the figure, with the head covered by horizontal bangs. Some historians have suggested that this could represent a headdress or even rows of plaited hair. Venus’ arms are visible but are very small, and insignificant when compared to the larger parts of the figurine’s body.

Interpretations

While the theory of this piece of Paleolithic art as a representation of fertility was generally accepted for years by archaeologists and historians, in recent years there have been criticisms and arguments within the fields of art history and archaeology about this portrayal, leading to much speculation and several interpretations of the piece.

In general, historians believe that these fertility goddess artifacts were used in rituals, and were celebrated for their links to fertility, as well as femininity and eroticism.

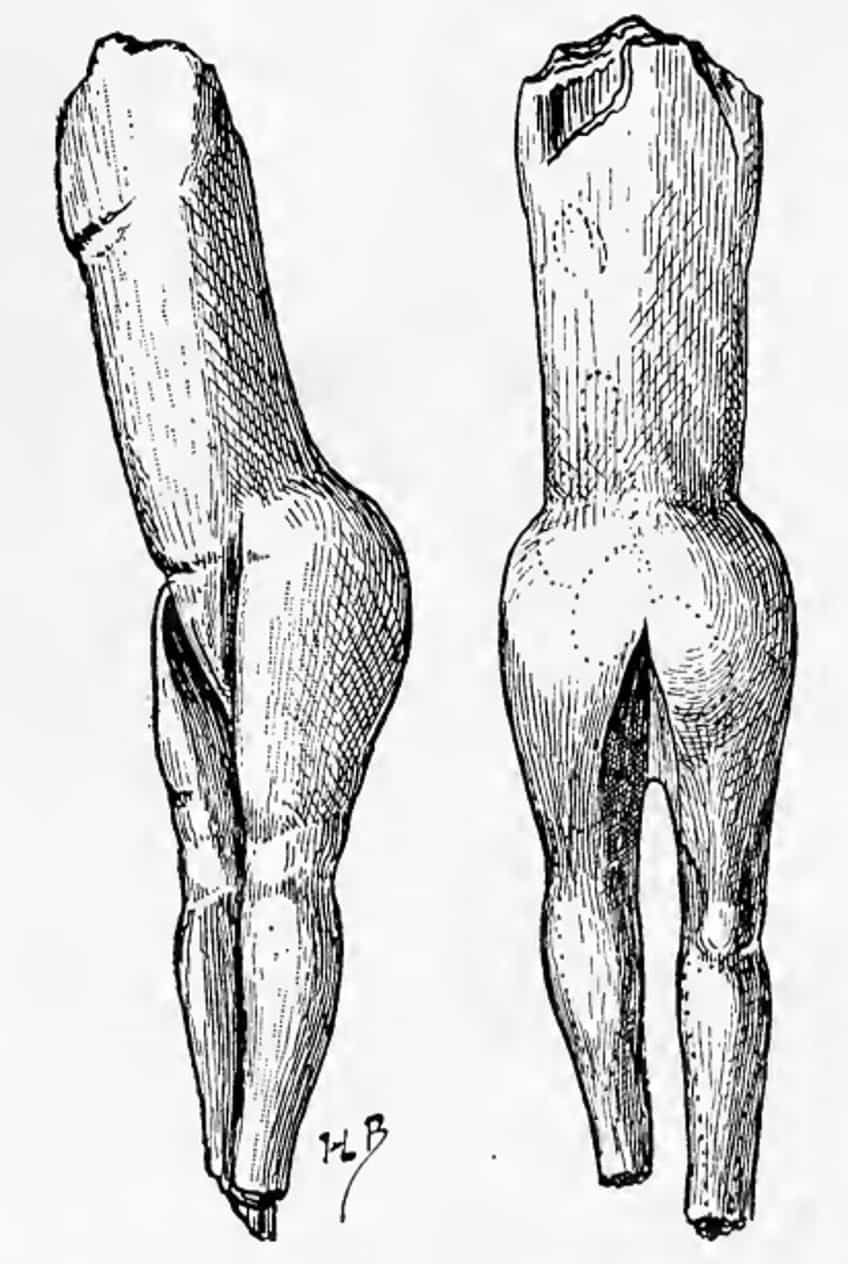

Some historians believe that the Venus of Willendorf may have been used as an aphrodisiac, made by men for the pleasure and appreciation of men. This theory was further examined by amateur archaeologist Paul Hurault, who discovered a similar figure in 1864 and named it Vénus Impudique for its association with sex and desire rather than motherhood and fertility.

Anthropologist Catherine McCoid noted that this theory, and the assumption that this work of art was made by men for men, comes from an inherent male bias, and it was this bias that clouded so many of the theories surrounding the Venus of Willendorf, as well as art history in general.

In fact, the first figurine ever discovered was retroactively titled The Venus Impudique (date unknown), which is a French name that translates to “the immodest Venus” due to the lack of coverage that was often seen in Roman statues posed in what was known as Venus Pudica or “modest Venus”.

Some scholars have rejected the use of the “Venus” title, hence why the piece is also known as the “Woman of Willendorf” or the “Woman from Willendorf”.

Alternative Theories

In contrast, McCoid and fellow historian, Leroy McDermott theorized that the piece of Paleolithic art may have been created by a woman, as a self-portrait. This hypothesis comes from the connection between how the emphasized proportions are presented to how a woman’s body parts would look when looking down at one’s own body. Given that the prehistoric age didn’t have mirrors or many reflective surfaces, this was the primary way they would view their bodies.

The lack of a recognizable face adds to this theory, as the woman who hypothetically sculpted it would not be able to see their own face without a mirror.

This theory has been argued against, however, by historian, Michael S. Bisson, who argued that these Neolithic women would have access to the reflective surfaces of water, whether that be lakes, rivers, or simply puddles.

Another scholar also suggested that the “Venus of Willendorf” was created by a woman, but that the over-exaggerated body parts stemmed from the way in which the woman viewed herself, describing it as a “the foreshortening effect of self-inspection.”

Some scholars even went so far as to claim that the shapely Venus figurines represented the non-European Neolithic woman, while the thinner figurines represented European Neolithic women, which archaeologist Tosca Snijdelaar argues to be a very racist interpretation. Snijdelaar asserts that the people of the Stone age may have used the Venus of Willendorf and similar pieces for talismans or idols of protection, that were either worn or kept around the home to be used in ritualistic processes. This theory would mean that within the societies these people lived in, the Neolithic woman was a symbol of power.

Snijdelaar, looking into the history of the human species, also claimed that when feeling anxious, frightened, or even threatened, the human body can experience symptoms of arousal, theorizing that these prehistoric humans likely associated this fear response with certain physical characteristics, and that association can be seen in the Venus figurines.

A Venus of Willendorf Analysis

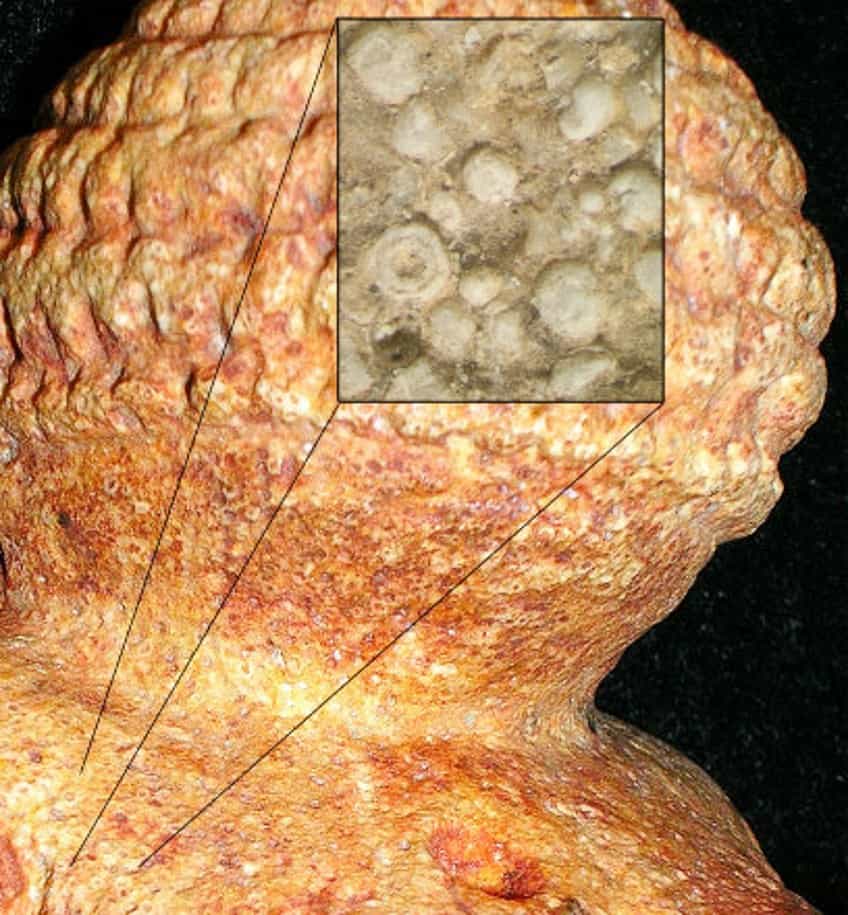

Given the amount of mystery surrounding the Venus of Willendorf, the Natural History Museum of Vienna partnered with Walpurga Antl-Weiser to solve the mystery behind the enigmatic piece of prehistoric art. The research team examined the statuette using what is known as micro-computed tomography, a technique that uses extraordinarily high-definition photography to look at cross-sections of objects, pieces, and in this case, works of art.

These micro-computed tomographic scans allowed researchers to examine the hemispherical cavities that can be seen dotted across the surface of the Venus.

They hypothesized that as the sculpture was carved, some limonites (iron ores consisting of hydrated iron oxides in various compositions) in the stone must have broken out, leaving the cavities. Fortunately, a piece of limonite appears to have fallen out of the naval area of the figure, which meant that the sculptor’s work was done for them when it comes to that part of the Venus’ body.

It was from these scans that the origins of the material were assigned, with the team believing that the stone used for the statue matches almost perfectly with the oolitic limestone found in Northern Italy, while also believing that it could possibly be from Ukraine.

The tomography scans also allowed the team to find that the limestone was not homogenous inside, which greatly assisted in locating the stone’s origins.

The stone was filled with a pattern of layers, each with different densities. The team also discovered small pieces of shells baked into the stone. The shells helped shorten the radius of potential countries of origin, from France to Eastern Ukraine.

One thing that is clear about the Venus of Willendorf is that it exists as an artifact of a prehistoric group or community of people, specifically Neolithic women. The term artifact, when it comes to art, refers to an object or piece that reflects the artist and their creed, and its beauty is developed through the skill of that artist. It is certainly unlikely that those who lived in the Upper Palaeolithic period gave much thought to what it meant to be an artist, it is clear through the pieces found that pieces of art like the Venus of Willendorf were made with skill, and reflected the social context it was created in.

The portability of the piece also tells us something about the environment in which it was created; a group of people who moved around, nomads or hunter-gatherers, who were some of the first groups of modern humans said to exist in Europe. Researchers believed that the move from Northern Italy to Willendorf must have involved a roughly 600-mile route, which would have also required crossing the Danube River, which currently spans 1775.26 miles long and up to 0.93 miles wide, and is the second-largest river in Europe.

One researcher, Gerhard Weber, estimates that the statue was likely a very treasured possession if it was carried that far, likely praised and cherished for several generations.

Archaeologists and historians stated that the Venus statue was made in a harsh environment with a very cold climate; likely part of Europe’s last Ice Age, where characteristics like fertility and obesity would be highly praised and desired, as these characteristics were associated with reproduction. This is likely why the breasts and pelvic area of Venus were so emphasized; as it would be what the artist valued. The large bottom area of the piece, or the steatopygia, would naturally be highly valued in a time of hunger and coldness, where being obese would be considered a sign of wealth or privilege.

The artist, and the community in which they lived, clearly had a fixation on reproductivity.

This fixation, according to neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran, comes from the neurological principle known as the “peak shift.” This principle refers to when animals respond more strongly to exaggerated versions of the training stimuli. In the case of the Venus of Willendorf, it refers to when individuals respond positively to exaggerated features that have positive associations. The peak shift principle can often be found in art, where the more intended pleasurable elements are refined and emphasized.

The viewer tends to be drawn toward these features, and as Ramachandran states, art doesn’t exist to be a realistic representation but rather deliberate exaggerations, distortions, and hyperboles to create a pleasurable and rich viewing experience.

These exaggerations and distortions are not random, however, with the artist specifically highlighting what they want the viewer to be drawn to. In artistic depictions of the human figure alone, there is a clear exaggeration. With Michelangelo, for example, there is a clear emphasis on the musculature of his figures. With Renoir, there is a clear emphasis on the rounder figure.

The Venus of Willendorf, considered the oldest Venus statue, is one of the most iconic pieces of art history, not only representing the Neolithic woman but also representing what the artist and the community they lived in valued from these women. This prehistoric approach to the human body is especially significant in how openly it is presented, especially when compared to other statues that share its name. The Venus of Willendorf does not cover itself up in the way the Venus Pudica statues usually would, as was the norm during the Hellenistic movement.

The analysis of the “Venus of Willendorf” is open to several interpretations and theories within the art world, with many scholars having their own perspectives on the figurine. Today, this fertility goddess statue can be considered a refreshing representation of the female body, thus becoming a figure of body positivity in the art world.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Does the Venus of Willendorf Represent?

The Venus of Willendorf figurine is the subject of many interpretations and theories, but it has been suggested that it represents a figure of fertility, a good-luck totem or talisman, a maternal goddess symbol, or an even an aphrodisiac made by men for the pleasure and appreciation of men.

What Kind of Art Is the Venus of Willendorf?

The Venus of Willendorf is an 11.1-centimeter figurine made of oolitic limestone. It is only one example of many Upper Paleolithic figures that have been associated with fertility.

What Do the Venus Figurines Present?

The Venus figurines are small statues, or statuettes, that depict obese women. Archaeologists and historians believed them to have been associated with fertility and beauty by the prehistoric people who carved and sculpted them. The name Venus comes from the Roman goddess of love, beauty, sex, and fertility. Most statues and figures that are meant to represent these characteristics are given the title of Venus, either by the artist or retroactively by art historians.

Why Is the Venus of Willendorf So Famous?

The Venus of Willendorf is an important figure in the field of art history because it is believed to have been crafted between 30,000 and 25,000 BCE, which means that it would be one of the world’s oldest known works of art that have been discovered.

What Was the Venus of Willendorf Made Of?

The Venus of Willendorf figurine was carved from oolitic limestone and decoratively tinged with red ochre.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, ““Venus of Willendorf” – Figurative Sculpture from the Paleolithic.” Art in Context. June 22, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/venus-of-willendorf/

Meyer, I. (2022, 22 June). “Venus of Willendorf” – Figurative Sculpture from the Paleolithic. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/venus-of-willendorf/

Meyer, Isabella. ““Venus of Willendorf” – Figurative Sculpture from the Paleolithic.” Art in Context, June 22, 2022. https://artincontext.org/venus-of-willendorf/.