“Fountain” by Marcel Duchamp – Duchamp’s Controversial Urinal Art

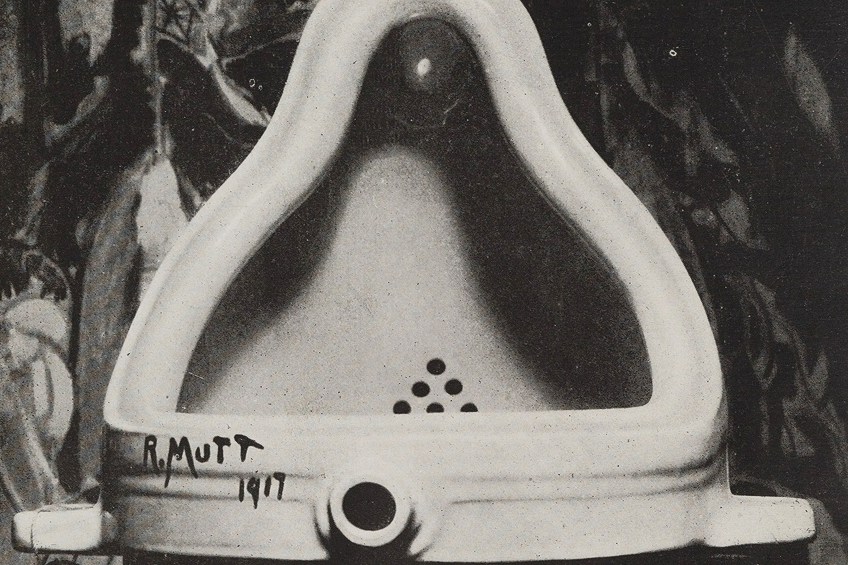

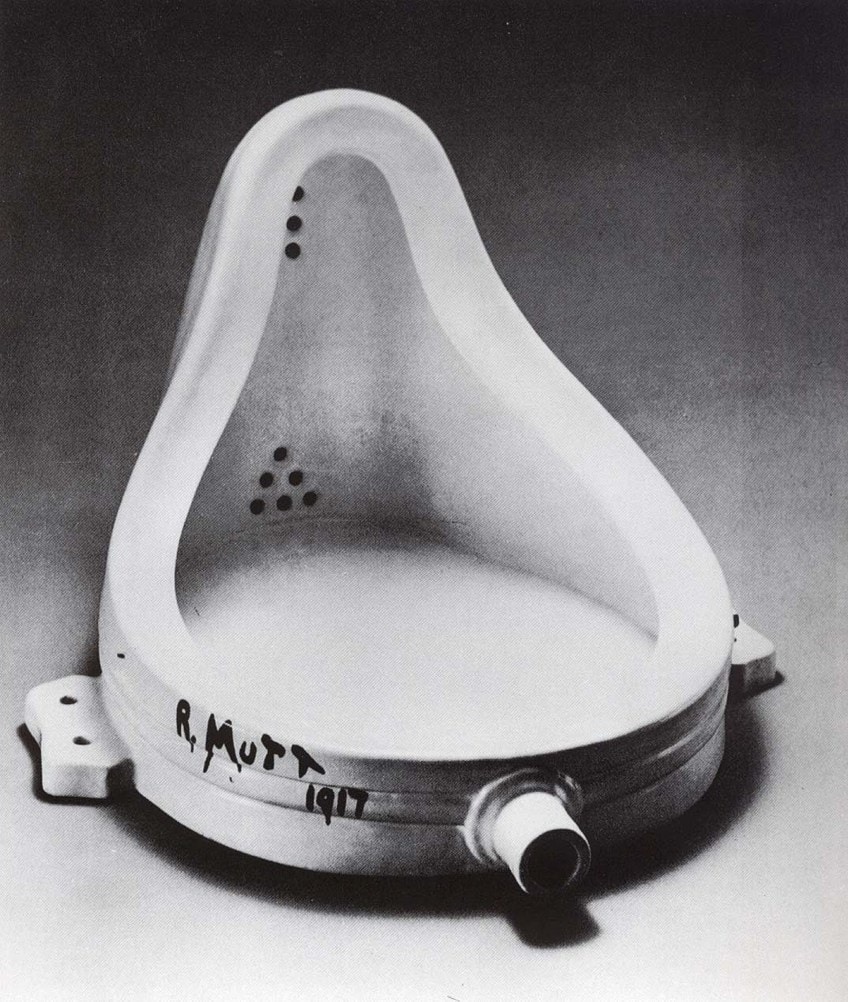

Fountain by Marcel Duchamp is a 1917 readymade artwork that is comprised of a porcelain urinal marked “R. Mutt”. Duchamp remarked that his urinal artwork is “an ordinary item lifted to the status of an artwork by the creator’s exercise of choice.” The Fountain sculpture’s placement was changed from its normal placement in the artist’s display. The committee did not openly reject the conceptual artwork because society regulations indicated that all entries from creators who paid the price would be admitted, but the piece was never displayed.

Table of Contents

An Introduction to Fountain (1917) by Marcel Duchamp

| Date Completed | 1917 |

| Medium | Porcelain |

| Dimensions | 61 cm |

| Current Location | Lost |

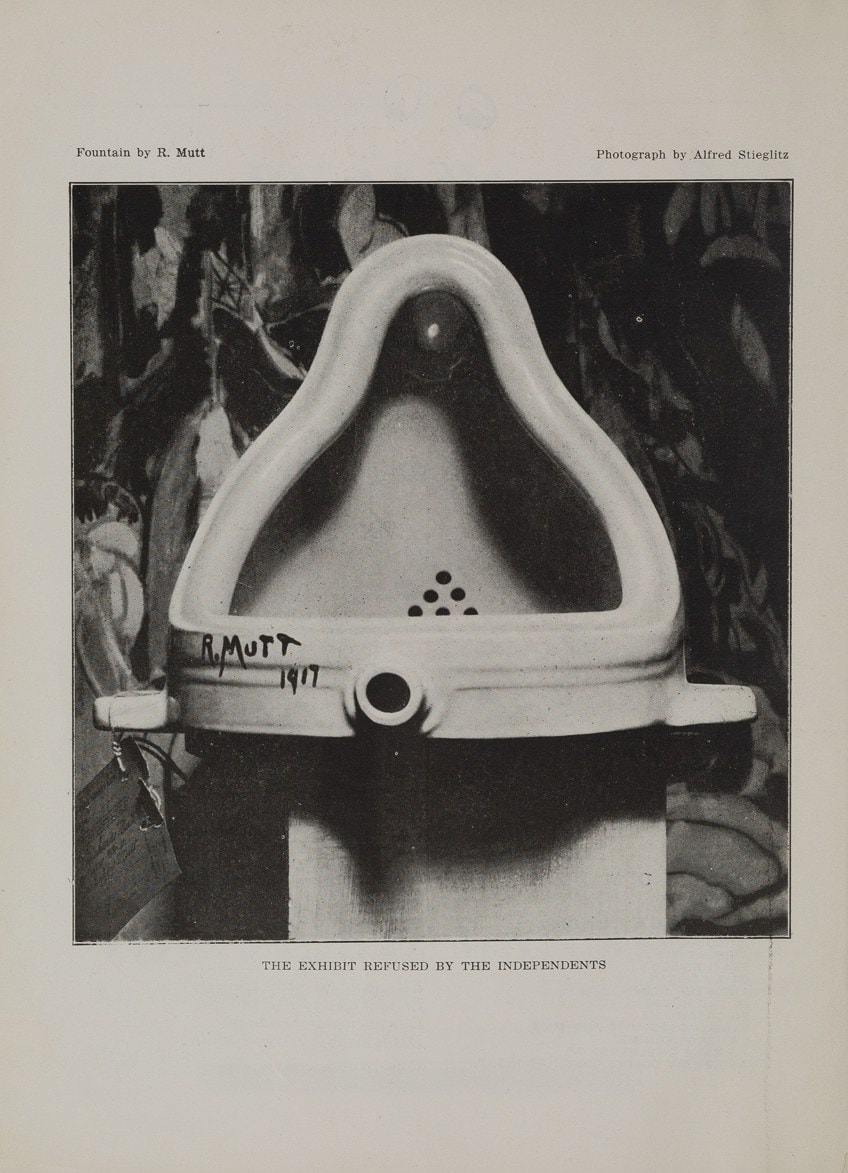

Art critics and avant-garde thinkers see the Duchamp urinal as an important landmark in 20th-century artwork. Some believe Duchamp’s Fountain was originally created by Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. The urinal artwork was shot in Alfred Stieglitz’s studio after its removal.

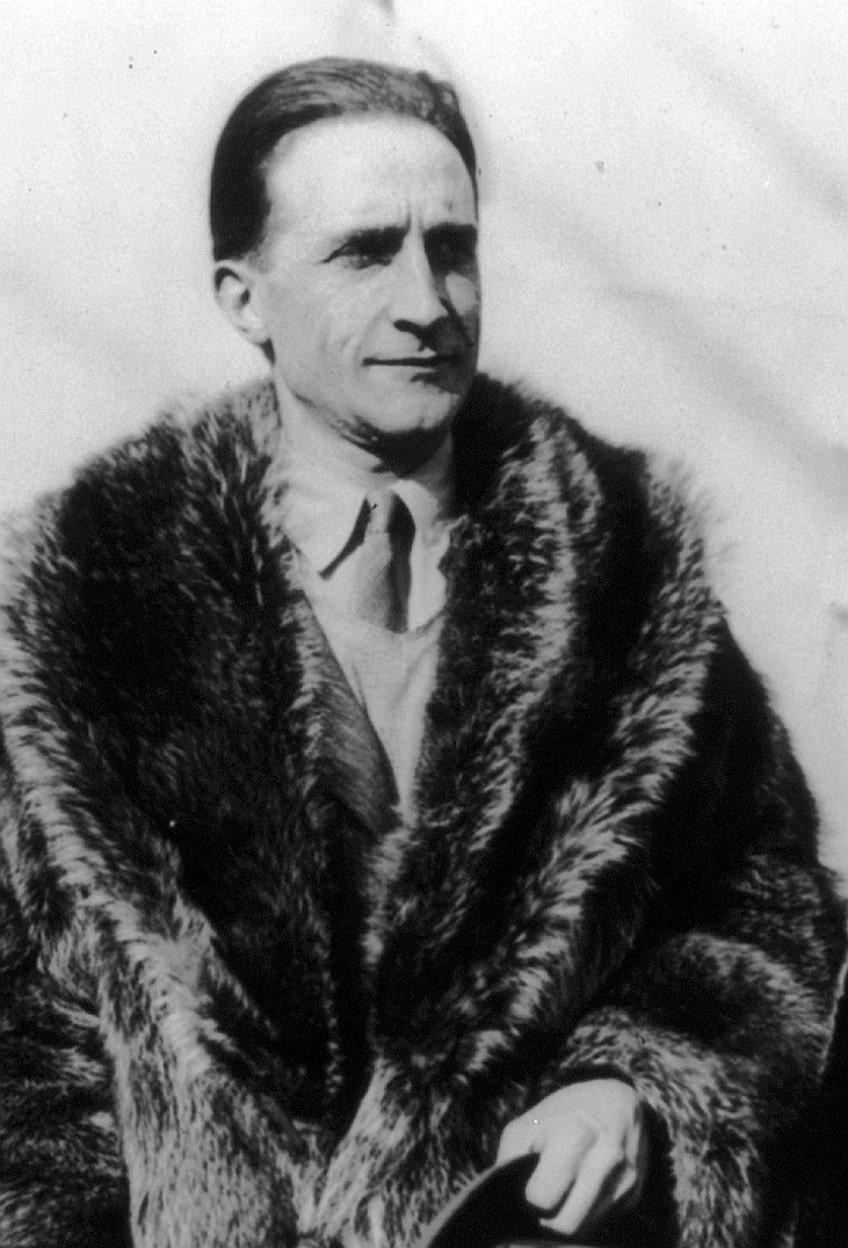

The Artist of the Fountain Sculpture: Marcel Duchamp

| Nationality | French-American |

| Date of Birth | 28 July 1887 |

| Place of Birth | Blainville- Crevon, France |

| Date of Death | 2 October 1968 |

Duchamp was a sculptor, painter, and writer known for his work in Dada, Cubism, and Conceptual art. Duchamp is often considered as one of the three artists who contributed to characterizing the revolutionary breakthroughs in the plastic arts in the early 20th century, credited for key advances in sculpture and painting.

Duchamp had a huge influence on modern art, and he was a pivotal figure in the creation of conceptual art.

As World War I commenced, he had dismissed the works of many of his contemporaries as “retinal” artwork, art that was merely meant to satisfy the sight. Duchamp, on the other hand, desired to utilize art to serve their thinking. Many commentators see Duchamp as one of the twentieth century’s most influential artists, and his work affected the evolution of post–World War I Western art. He counseled modern art collectors, influencing Western art preferences during this time period.

Through subversive anti-art, Duchamp questioned traditional thinking about artistic processes and criticized the rising art market.

Studying Duchamp’s Urinal Artwork

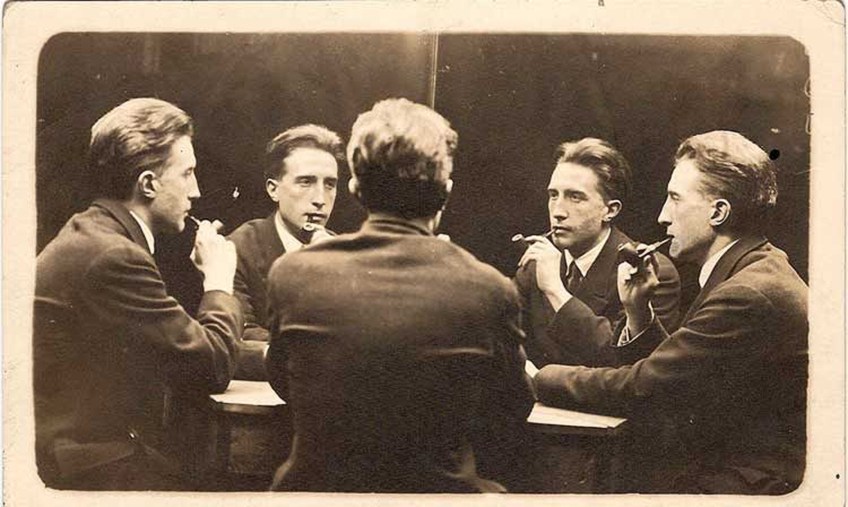

Marcel Duchamp came to North America just a few years before the production of his Fountain sculpture, and he was involved in the formation of an anti-established art, proto-Dada social scene in New York City alongside Man Ray, Francis Picabia, and Beatrice Wood. Rumors circulated in early 1917 that Duchamp was concentrating on a Cubist artwork in anticipation of the greatest modern art show ever held in the United States. Those who had planned to see it were dismayed when it did not materialize at the exhibition.

However, the artwork was most likely never made.

Origin

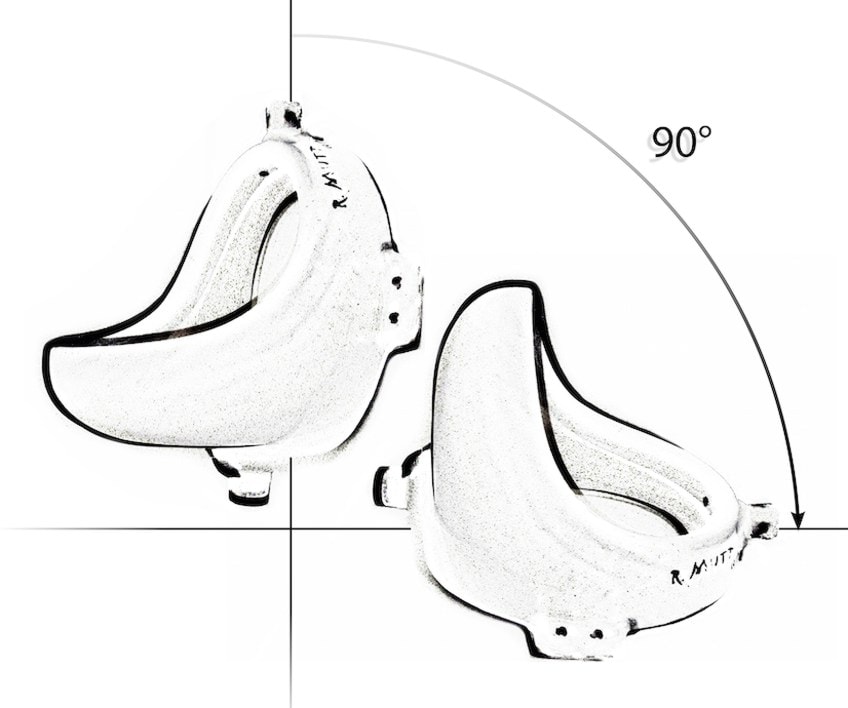

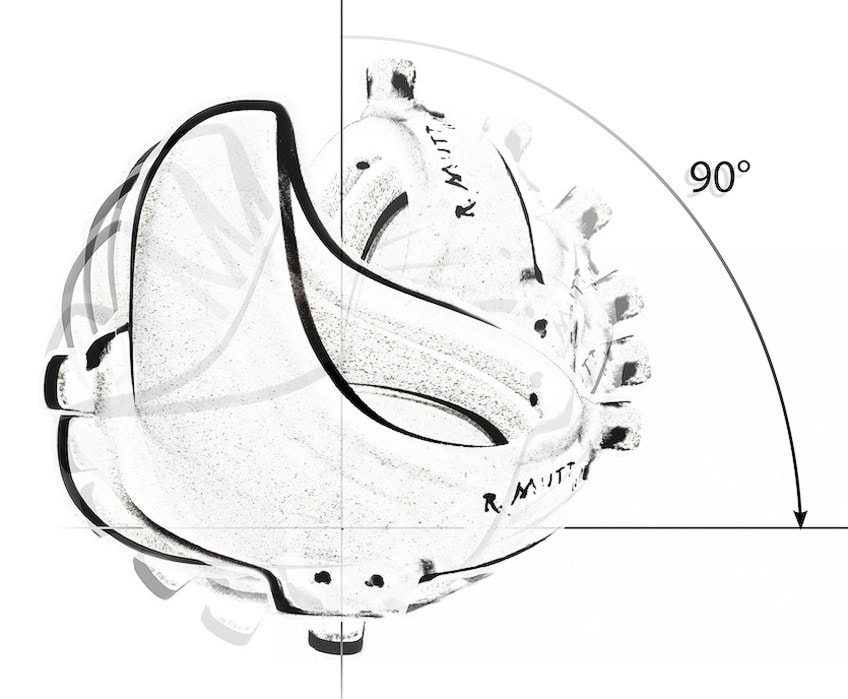

According to one account, Duchamp began working on the conceptual artwork after purchasing a conventional model urinal from the J. L. Mott Iron Works. The artist carried the toilet to his workshop, turned it 90 degrees from its initial position, and inscribed “R. Mutt 1917” on it.

Duchamp also included Richard (“Money-Bags” in French) Mutt, or R. Mutt, who was a governing fellow of the Society of Independent Artists at that moment. Duchamp’s Fountain was withheld from display during the show after much dispute among the board members (many of whom had no idea Duchamp had contributed it because he had done so “under an alias”).

Duchamp left the Board of Directors and, as a result, the work was put on hold.

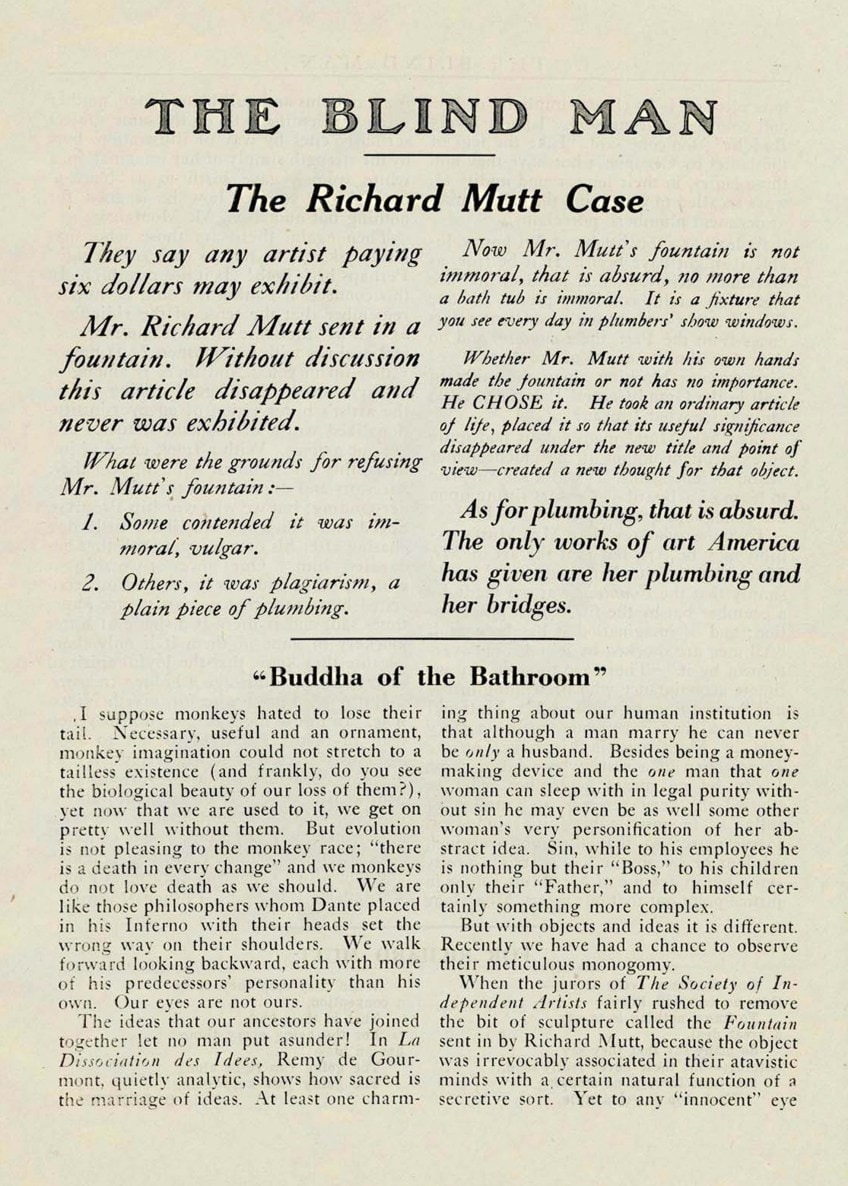

In the second edition of The Blind Man (1917), which contained a photo of the sculpture and correspondence from Alfred Stieglitz, as well as articles by Louise Norton and Allen Arensberg, the New York Dadaists sparked discussion concerning Fountain and its rejection.

An editorial accompanying the shot, probably authored by Wood, made an assertion that would emerge to be significant in the context of subsequent works of art: “It makes no difference whether Mr. Mutt built the fountain himself or not. It was his decision. He took a common thing and arranged it in such a way that its usefulness vanished under the new title and point of view — he produced a new notion for that object. The only pieces of art America have provided are her pipes and her bridge, defending the piece as art.”

The essay continues, “The piece’s purpose, according to Duchamp, was to transfer the emphasis of art from physical production to cerebral interpretation.”

Stieglitz described his shot of Fountain as follows: “The ‘Urinal’ photograph is truly amazing—everyone who has seen it believes it is stunning—and they are right.” The Duchamp urinal, according to an article published in 1918 by Mercure de France, represents a seated Buddha.

The Independents said that the piece was indecent and obscene, that it was plagiarized, and that it was a corporate piece of piping. According to Apollinaire, R. Mutt stated that the art was not sinful because comparable pieces could be seen every day in bathroom and bathing supply stores. Regarding the second issue, R. Mutt stated that the fact that the Fountain sculpture was not created by the artist’s hand was irrelevant.

The significance was in the artist’s decision. The artist picked an everyday object, eliminated its typical value by giving it a new label, and gave the thing a new purely aesthetic meaning from this perspective.

The Fountain sculpture was lost shortly after its first showing. The best hypothesis is that it was thrown away like trash by Stieglitz, as was the case with many of Duchamp’s early readymades. However, legend has it that Duchamp gave the original fountain to Richard Mutt rather than throwing it away.

Duchamp’s urinal sparked a response that lasted for weeks after the display was submitted.

In Boston, an article was published. It stated: A toilet fixture was submitted as a “piece of art” by Richard Mutt, a member of the organization who is not connected to our buddy from the “Mutt and Jeff” cartoons. According to the official record of the event of its removal, “Richard Mutt has threatened to sue the directors for removing a pedestal-mounted bathroom fixture that he had presented as a ‘piece of art.'”

Because the organization had decided that there would be “no jury” to deliberate on the merits of the works submitted, some of the directors wanted it to stay. Other directors claimed it was inappropriate in a meeting, and the majority of the board voted it down. As a result, Marcel Duchamp resigned from the Board of Directors. Mr. Mutt now demands more than just his dues.”

In 1935, Duchamp began manufacturing small replicas of his fountain, first in papier-mâché, then in ceramic, for his various iterations of a small museum “retrospective”.

Interpretations

Duchamp’s Fountain is undoubtedly the most famous of the readymade works due to the symbolic importance of the toilet forces the philosophical challenge offered by the readymade to its most emotional conclusion.

According to Stephen Hicks, Duchamp, who was very much well-educated in the art history of Europe, was definitely making a contentious comment with the Duchamp urinal: Duchamp was browsing at a plumbing store; thus the artist isn’t a brilliant creator. The artwork was mass-produced in a factory and is not unique. Art is not exhilarating or ennobling; at most, it is perplexing, and it almost always leaves a bad taste in one’s mouth.

Above and beyond that, Duchamp did not show simply any ready-made object. His message was apparent when he chose the urinal: Art seems to be something you urinate on.

The effect of Duchamp’s Fountain shifted people’s perceptions of art because of his emphasis on “cerebral art” rather than merely “retinal art,” as this was a tool to interact to engage potential audiences in a thought-provoking manner rather than simply satisfying the aesthetic established order of “having turned from classicism to modernity.” Because the photograph shot by Stieglitz is the only photograph of the initial artwork, there are some views of the Fountain based on this photograph rather than copies.

According to Tomkins: “Arensberg had mentioned a ‘beautiful figure,’ and it doesn’t take much imagination to envision the shrouded head of a classic Renaissance Madonna, a sitting Buddha, or, maybe more to the point, one of Brâncuși’s polished sensual forms” in the upside-down urinal’s softly flowing curves. Tim Martin has claimed that the fountain’s horizontal placement has significant sexual overtones, building on the erotic connotation associated with Brancusi’s work.

According to Martin, “Locating the urinal horizontally seems more docile and feminine despite being a container suited for the operation of the male penis.”

According to Rhonda Roland Shearer, the Stieglitz shot is a composite of many photographs, while William Camfield has never been able to connect the urinal seen in the photo to any urinals discovered in period catalogs. In an interview with Otto Hahn, Duchamp claimed that he chose a urinal because it was unpleasant.

According to Duchamp, the choice of a urinal “arose from the concept of conducting a taste experiment: pick the thing with the least probability of being loved. A urinal is something that very few people consider to be lovely.”

The visual and verbal parts, structured as an emblem, provide a clever interaction that allows us to delve further into the mechanics that Fountain actively stages. On the one end, there are the mirror effects of sketching and engraving, which, while outwardly similar, necessitate a deliberate movement from one form of art to the next. However, since this toilet, like the one in 1917, has been turned 90 degrees, the image does indeed have an inner mirror return.

This inner movement excludes the item from its everyday function as a receptacle and reawakens its poetic possibilities as a fountain, that is, as a waterworks device.

Legacy

Duchamp was clear that he intended to “de-deify” the artist. The readymades offer an alternative to rigid either-or aesthetic ideas. They symbolize a Copernican change in art. Fountain is an image that was not created by an artist’s hands. The fountain presents us with a unique creation that is still original but in a new intellectual and philosophical position.

It is a representation of the Kantian sublime: a piece of art that transcends form while remaining understandable, an item that kills an idea while enabling it to grow stronger.

Interventions

Several performers sought to add to the sculpture by urinating in it. Kendell Geers, a South African-born artist, gained worldwide attention in 1993 when he peed into the Duchamp urinal during an exhibition in Venice. In 1993, musician Brian Eno said that he successfully urinated in Fountain when it was on display at the MoMA. He conceded that it was simply a technical achievement since he had to urinate in a tube beforehand so that the fluid could be sent through a crack between the protective glass.

In the spring of 2000, two performance artists attempted to urinate on the fountain on exhibit at the newly opened Tate Modern.

They were, however, prohibited from immediately soiling the sculpture due to its Perspex casing. The Tate, which disputed that the pair had succeeded in urinating into the sculpture, barred them from the grounds, claiming that they were endangering “pieces of art and our workers.”

When questioned why they were compelled to contribute to Duchamp’s artwork, one of the performance artists stated, “The presence of the urinal is an open invitation. As Duchamp himself stated, it is the artist’s decision. He decides what is art. We simply added to it.”

On January 4, 2006, “Fountain” was assaulted while on exhibit in the Dada show at the Pompidou Center in Paris by Pierre Pinoncelli, best known for breaking two of the artwork’s eight replicas.

During the assault on the artwork, he used a hammer, which created a little chip. The attack, according to Pinoncelli, was an act of performance art that Marcel Duchamp would have enjoyed. Pinoncelli also urinated into the sculpture when it was on show at Nimes, Southern France, in 1993. Both of Pinoncelli’s performances are inspired by the intervention or maneuvering of neo-Dadaists and Viennese Actionists.

Reinterpretations

In 1991 and 1996, Sherrie Levine produced bronze replicas. They are considered a “tribute to Duchamp’s famed readymade.” Levine is re-evaluating 3D items within the area of appropriation, such as readymades, to mass-produced digital art by doing so. Adding to Duchamp’s bold move, Levine elevates the materiality and polish of his gesture, transforming it into an “art object.” As a feminist designer, Levine recreates works by masculine painters that seized patriarchal supremacy in art history. Saul Melman built a substantially bigger replica for Burning Man in 2003 and then burnt it.

Duchamp’s effect on American artists grew enormously beginning in the 1950s.

According to Life magazine, he was “probably the world’s most prominent Dadaist,” Dada’s “spiritual leader”. His readymades were in the permanent collections of American institutions by the mid-1950s. In 1961, Duchamp allegedly stated in correspondence with Hans Richter: “This Neo-Dada, also known as Pop Art, is a convenient escape route and is based on what Dada did. When I found the ready-mades, I tried to discourage them. They have found aesthetic beauty in my readymades in Neo-Dada; I put the bottle rack and the urinal in their faces as a test, and now they adore them for their visual value.”

“Fountain” is among Duchamp’s most well-known artworks and is widely regarded as a 20th-century art icon. The missing original was a typical urinal, generally displayed on its back for display grounds rather than erect, and was written and signed “R. Mutt 1917”. Duchamp subsequently remembered that the inspiration for the urinal artwork came from a conversation with collector Walter Arensberg.

Take a look at our Duchamp Fountain webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Where Did the Duchamp Fountain Originate?

Marcel Duchamp bought a urinal from a hygienic ware manufacturer and submitted – or planned for it to be presented – as an installation by a so-called R. Mutt to the newly formed Society of Independent Artists, which Duchamp had assisted to organize and promote. The Society’s directors, who were required by the Society’s rules to accept all members’ proposals, objected to Fountain, feeling that sanitary goods – especially one connected with human waste – could not be deemed a work of art and was also immoral.

Who Was Marcel Duchamp?

Duchamp is recognized with key innovations in sculpture and painting and is usually considered as one of the three artists that helped define the transformative successes in the plastic arts in the early years of the 20th century. Duchamp had a significant impact on contemporary art and was a key player in the development of conceptual art. At the start of World War I, he had condemned several of his colleagues’ works as so-called retinal artworks, or art that was only designed to keep the senses satisfied. Duchamp, on the other hand, intended to use art to forward their ideas.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, ““Fountain” by Marcel Duchamp – Duchamp’s Controversial Urinal Art.” Art in Context. May 31, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/fountain-by-marcel-duchamp/

Meyer, I. (2022, 31 May). “Fountain” by Marcel Duchamp – Duchamp’s Controversial Urinal Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/fountain-by-marcel-duchamp/

Meyer, Isabella. ““Fountain” by Marcel Duchamp – Duchamp’s Controversial Urinal Art.” Art in Context, May 31, 2022. https://artincontext.org/fountain-by-marcel-duchamp/.