“Augustus of Prima Porta” – Iconic Portrait of Rome’s First Emperor

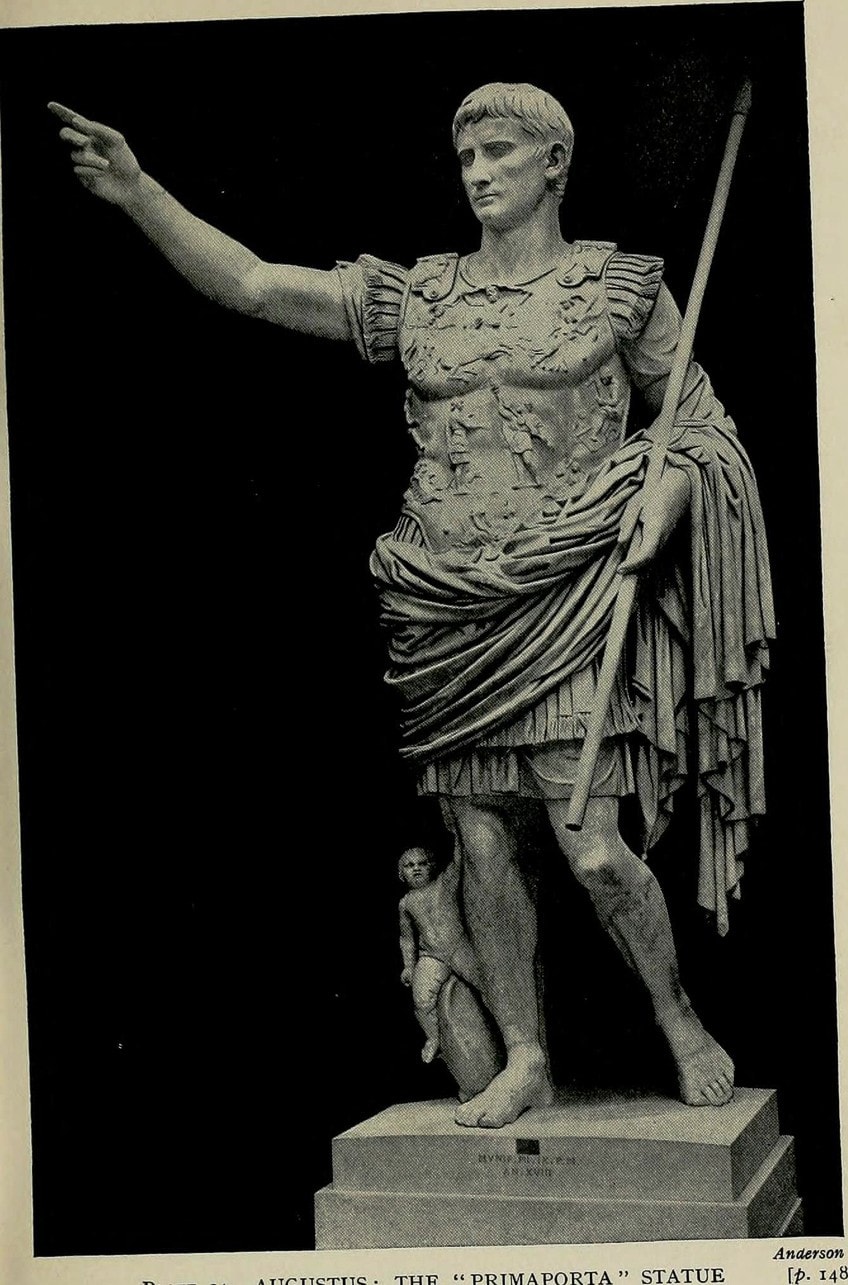

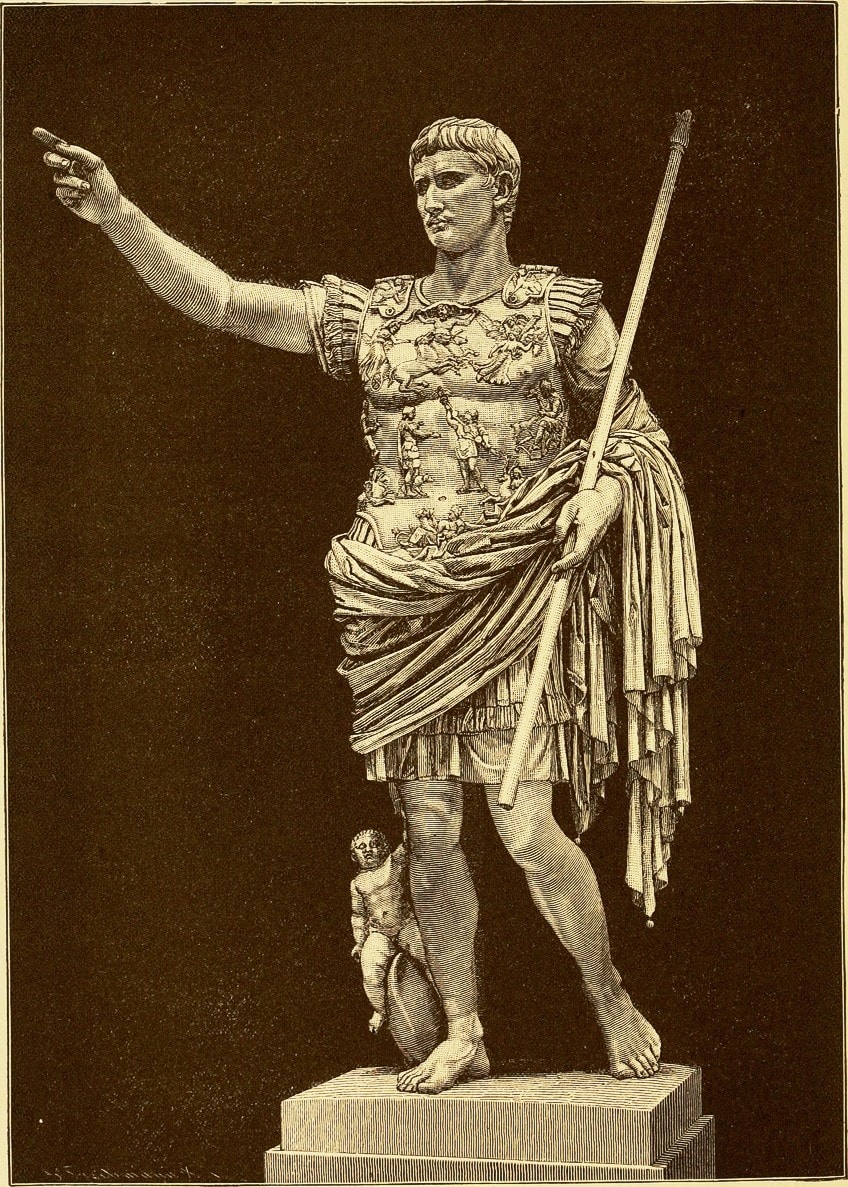

The Caesar Augustus statue, better known as the Augustus of Prima Porta, portrays the Roman Empire’s first emperor. The Caesar Augustus statue stands in a manner popular in Roman art known as the contrapposto pose, where the weight of the statue relies on one leg. This monument may appear to be only a picture of Augustus as a public speaker and commander at first sight, but it also conveys a great deal about the emperor’s authority and philosophy.

Table of Contents

Augustus of Prima Porta (c. 1st Century AD)

| Date Completed | c. 1st century AD |

| Medium | White marble |

| Dimensions | 2.08 m |

| Current Location | Vatican Museum, Rome |

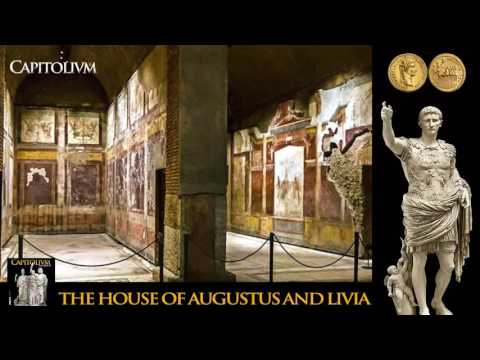

The sculpture was unearthed on the 20th of April, 1863, at the Villa of Livia during archaeological investigations led by Giuseppe Gagliardi. The figure, sculpted by master Greek artists, is said to be a replica of a missing bronze piece once on exhibit in Rome.

The sculpture has become the most well-known of Augustus’ representations and one of the most renowned statues of the ancient world since its unearthing.

The Original

The artwork alludes to Augustus’ most major diplomatic achievement, the Parthian reinstatement of the Roman eagles in 20 BC. As a result, the bronze original was most likely created after 20 BC. Augustus’ barefooted image is meant to be a divine representation since this was a common portrayal of deities or warriors in classical imagery. The marble duplicate would have been made somewhere between that period and Livia’s death in 29 AD.

The “Augustus” statue could have been ordered by Tiberius, Augustus’s successor.

This theory is supported by the fact that Tiberius, who acted as a middleman in the eagles’ rescue, is also shown on the cuirass. The breastplate motif would remind spectators of Tiberius’ relationship with the venerated emperor and establish a connection between both regimes, as this deed was the greatest tribute he had rendered to Augustus.

It’s also probable that Livia, Augustus’s wife at the moment of his death, sponsored it.

Style

Augustus is depicted in his function as “Imperator,” or army leader, implying that the sculpture should be part of a memorial monument to his recent successes; he is dressed in military garb, wielding a consular baton, and commanding the troops with his right hand raised in a rhetorical stance. The bas-reliefs on his plated cuirass have a complicated metaphorical and political purpose, referring to a variety of Roman deities, notably Mars, the god of battle, as well as embodiments of the most recent regions he conquered. Augustus’ deeds are illuminated at the top by the Sun’s chariot.

The statue is an idealized representation of Augustus in a conventional Roman orator’s posture, based on the artist Polykleitos’ “Doryphoros” statue from the 5th century BC.

The contrapposto pose of the Doryphoros is applied here, generating diagonals between stiff and relaxed limbs, a motif common in ancient art. The statue’s legs are in a Doryphoros-like position. As though the statue is going forward, the right leg is stiff and the left leg is loose. The Doryphoros‘ misidentification as the warrior Achilles during the Roman period made the figure all the more fitting for this depiction.

Despite the Republican impact on the portrait head, the whole style is more akin to the Hellenistic idealized version than Roman reality. The adoption of Greek art is the explanation for this stylistic transition. The Romans returned with vast quantities of Greek art after each conquest. The influx of Greek artifacts influenced Roman aesthetic sensibilities, and these works of art became symbols of wealth and prestige for the Roman ruling class.

Considering the realism with which Augustus’ features are shown, the distant and serene look of his face, as well as the traditional contrapposto pose, anatomical dimensions, and the richly draped “commander’s garment,” have been romanticized.

The addition of Cupid mounting a dolphin as a supporting structure for the monument, on the other hand, indicates Augustus’ legendary link to the goddess Venus through his adopted father Julius Caesar. The clear Greek influence in aesthetics and signifier for official sculptural portraits, which became devices of governmental rhetoric under the Roman emperors, is a core component of the Augustan philosophical campaign, a transition from the Roman Republican era symbology, which saw wise characteristics as icons of somber character.

As a result, the Prima Porta monument represents a deliberate inversion of iconography from the Greek classical and Hellenistic periods, when youth and power were revered as indicators of leadership, with heroes being emulated and culminated in Alexander the Great himself.

The political purpose of such a monument was clear: to demonstrate to Rome that Emperor Augustus was extraordinary, similar to heroes deserving of being elevated to God status on Mount Olympus, and the ideal man to govern Rome.

Polychromy

The Augustus was almost certainly painted, but there are so few remnants left now that scholars have had to rely on antique watercolors and recent scientific research for proof. In the 1980s, Vincenz Brinkmann of Munich used UV light to investigate the use of color in ancient art.

The Vatican Museums have now created a replica of the monument in order to paint it in the supposed original hues, which were confirmed when the sculpture was cleaned in 1999.

However, some art historians have condemned this reconstruction as being unsubtle and overdone, while others have stated that the actual Augustus of Prima Porta and the painted copy have numerous noteworthy discrepancies. However, there is little documentation or investigation on the use of these hues due to the ongoing debate over the statue’s coloration. For the Tarraco Viva 2014 Festival, another duplicate was painted in a new color scheme.

The common appearance of Roman sculptures without their original paint has supported the belief that monochromy is the natural state for classical sculptures since at least the 18th century; nonetheless, surface treatment is now regarded as vital to the overall aesthetic of the sculpture. The works of polymath Lucian are an excellent illustration of how color was used in a work at the time “I’m afraid I’m blocking her most significant feature! Apelles’ remainder of the body was not overly white, but it was drenched with blood.”

The phrase goes on to say that a sculpture of the period is incomplete without its layer, which is applied to the monument to complete it. The meanings of each hue chosen for the Prima Porta are unknown; red is said to represent the military and monarchy.

Iconography

Augustus’ haircut consists of thick, separated strands of hair, with a strand exactly above the center of his forehead bordered by other strands. Two strands from the left stray onto the forehead, and three strands from the right, a hairdo originally seen on this statue. This hairdo also identifies this statue as Augustus when compared to his coinage picture, which might help date it.

Other haircuts of Augustus can be found on the Ara Pacis, for instance. This specific hairdo is employed as the initial indicator designating this portrait style of Augustus as the Prima Porta type.

The face is idealized, although not as much as the sculptures of Polykleitos. Augustus’ face is not flattened down and has characteristics that reflect his distinct traits. During Augustus’ reign, art saw significant changes, with the harsh realism that characterized the Republican age losing way to Greek influences, as shown in emperor portraits – idealizations encapsulating all the attributes that an outstanding man capable of ruling the Empire should possess.

Augustus let himself be shown in a monarchical way in earlier pictures, but gradually replaced them with more diplomatic ones that depicted him as “primus inter pares.” The head and neck were carved out of Parian marble separately and then fitted into the torso.

Breastplate Relief

The breastplate is sculpted in relief with several miniature figurines commemorating the restoration of the Roman legionary eagles surrendered to Parthia by Mark Antony in the 40s BC. According to the most accepted interpretation, the figure in the center represents a subdued Parthian ruler returning Crassus’s banner to an armored Roman.

According to another belief, the masculine figure represents the ideal personification of the Roman legions.

This was a hugely popular topic in Augustan marketing, as one of his biggest international accomplishments, and it had to be highlighted especially forcefully, because Augustus had been diverted from the war that the Roman people had expected by the Parthian military superiority, and had instead chosen diplomacy. A dog, or maybe a wolf, or, as per archaeologist Ascanio Modena Altieri, a she-wolf, Remus and Romulus’ nurse, can be seen beneath the armed figure. Women in grief sit on either side.

A figure with a sheathed sword on one side represents the peoples of the East obliged to pay tribute to Rome, while a figure with an unsheathed blade on the other side represents the enslaved Celts. The cuirass is unique in that it has a rear as well as a front. An armored cup with a wing above and gauntlets against a tree trunk can be found on the cuirass’ bottom right side. The statue was believed to have been fastened to a wall by an iron peg. This is most probably due to the incomplete back. None of these readings are without controversy.

The gods, on the other hand, most likely represent the events’ continuity and logical coherence – just as the sun and moon always rise, so Roman victories are assured and divinely authorized. Moreover, Augustus, the bearer of this armor, is linked to these victories.

Divine Status

Augustus did not want to be represented as a god during his lifetime, yet this monument has several carefully veiled allusions to the emperor’s “divine nature,” his genius. Augustus is depicted barefoot, implying that he is a hero and maybe a divus, as well as adding a civilian element to a somewhat military painting.

Being barefoot was traditionally only permitted on pictures of the gods, but it might also indicate that the sculpture is a posthumous copy of an Augustus figure from the city of Rome in which he was not barefoot.

The little Cupid riding a dolphin at his feet is an allusion to Augustus’ and his great uncle Julius Caesar’s claims that the Julian family was derived from the goddess Venus – a technique of claiming divine heritage without claiming full celestial rank. Cupid’s journey on the dolphin has political importance. It appears that Augustus conquered the Battle of Actium and vanquished Mark Antony, one of his main adversaries.

Type

Augustus’s Prima Porta-style sculptures, of which Augustus of Prima Porta is the most renowned example, were his most popular representational style. Around 27 BCE, this type was established to physically communicate the title Augustus, and it was duplicated full-length and in busts in various variants across the empire until his death in A.D.14.

However, the replicas never depicted Augustus as aged, instead portraying him as eternally young.

This was in keeping with the propaganda’s goals of displaying the Roman emperors’ power through traditional forms and cultural tales. This “type creates a visual contradiction that may be defined as sophisticated, timeless, and authoritative freshness” at its best.

Location

The sculpture of Augustus of Prima Porta was found at the Villa of Livia in 1863, but little is understood about the finding and its immediate aftermath due to insufficient archaeological notebooks that left current historians with confusing evidence. As a result, the statue’s actual placement within the home remains uncertain.

The subterranean complex, a location near a staircase, the villa’s atrium, or a laurel forest on the southeast corner of Prima Porta hill are all suggested locations. In comparison to the previous three, scholars believe the last one is less persuasive.

The argument that Augustus’ statue was discovered in the villa’s underground structure is based on the fact that Augustus’ left hand is holding a laurel branch rather than a spear. Scholars have speculated that if this theory is right, the Villa of Livia must have been adorned with laurel groves, with the reason for the adornment being the omen of the gallina alba.

Recent digs have uncovered the remains of pots used to grow laurel on the side of the Prima Porta hill in front of the subterranean complex, which Reeder says implies the villa may have had laurel groves and makes it more plausible that the statue was found there. Augustus, according to Suetonius, was afraid of lightning and frequently hid in ‘a subterranean vaulted room,’ which she believes was the underground complex, especially since laurels were supposed to give lightning protection at the time of Augustus.

Researchers who disagree with the hypothesis contend that while the pot fragments may have been used to plant laurel, they could also have been used to grow other plants like lemons. They further claim that Prima Porta Augustus was discovered at the bottom of the stairway leading to the underground structure, not the structure itself, according to an 1891 sketch drawn 25 years after the first excavation. The statue might have been transported to the basement from another place, such as the atrium, where it could be displayed on a rectangular framework that runs along the atrium’s south wall.

The sculpture would be the first item guests would see as they entered the atrium from the northeastern end, and they would see it from the left, which fulfills Kähler’s opinion that it should be observed from this location. The visitor’s gaze would meet Augustus’ right hand as they traveled across the atrium, thereby “getting” Augustus’ address.

Following Livia’s marriage to Octavian, an eagle deposited a hen with laurels onto Livia’s lap, which the Roman religious authorities saw as a symbol of benediction and divinity. The plant was commanded to be placed with great care at the villa Urbana, where it eventually flourished into a grove. When the Julio-Claudians achieved military victory, they would remove a laurel branch from the villa.

“Augustus of Prima Porta” is a white marble statue of a powerful and attractive young man in his armor that now resides in the Vatican Museum. An extremely realistic scenario plays out on his breastplate from the front. He’s positioned with his right foot in front of him and his left foot elevated slightly behind him. The style of the sculpture, which was created during Imperial Rome, is similar to that of other sculptures of the time. The fact that he is dressed in military uniform, using a baton, and addressing what we presume is his troops’ accords with the manner of previous leaders’ monuments we’ve seen.

Take a look at our Augustus statue webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Is the Caesar Augustus Statue Important in Roman Art?

The Augustus of Prima Porta is an example of how the ancients utilized art to spread propaganda. Overall, this monument depicts Augustus’ relationship to the past, his position as a military conqueror, his link to the heavens, and his function as the bearer of the Roman Peace, among other things. The Augustus of Prima Porta is an example of how the ancients utilized art to spread propaganda.

Where Was the Augustus Statue Found?

Augustus of Prima Porta’s sculpture was discovered at the Villa of Livia in 1863, but little is known about the discovery and its immediate aftermath due to a lack of archaeological notes, which has left present historians with conflicting data. As a consequence, the statue’s exact location within the house is unknown. Locations considered include the underground complex, a spot near a staircase, the villa’s atrium, or a laurel woodland on the southeast corner of Prima Porta hill. Scholars say the last one is less compelling than the prior three.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, ““Augustus of Prima Porta” – Iconic Portrait of Rome’s First Emperor.” Art in Context. May 21, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/augustus-of-prima-porta/