Famous Renaissance Sculptures – The Top Sculptures of the Renaissance

The Renaissance is the time period following the Middle Ages, spanning from the 15th to the 17th century. The word renaissance is of French origin and is defined as “rebirth”. This is name is fitting for this period as it is one of the most pivotal points in human history. During the Renaissance, humanity resurrected the quintessence of the Classical period in all eras of life. Science, politics, economics, and above all else, the arts. Some of the most revered paintings and sculptures in existence were created during the Renaissance.

Table of Contents

- 1 The History of Renaissance Sculpture Art

- 2 The 10 Most Famous Renaissance Sculptures to Exist

- 2.1 Gates of Paradise (c. 1425 – 1452) by Lorenzo Ghiberti

- 2.2 David (c. 1430 – 1440) by Donatello

- 2.3 Judith and Holofernes (c. 1455 – 1460) by Donatello

- 2.4 Pietà (c. 1498 – 1499) by Michelangelo

- 2.5 David (c. 1501 – 1504) by Michelangelo

- 2.6 Madonna of Bruges (c. 1501 – 1504) by Michelangelo

- 2.7 Hercules and Cacus (c. 1525 – 1534) by Bartolommeo Bandinelli

- 2.8 Perseus with the Head of Medusa (c. 1545 – 1554) by Benvenuto Cellini

- 2.9 The Deposition (c. 1547 – 1555) by Michelangelo

- 2.10 Abduction of a Sabine Woman (c. 1579 – 1583) by Giambologna

- 3 Frequently Asked Questions

The History of Renaissance Sculpture Art

Many complex factors sparked the start of the Renaissance period, such as increased cultural exchange due to trade routes and holy wars, innovations like the Gutenberg printing press, and the Black Death, which shook people’s unquestioning religious beliefs. However, one of the most important factors can be attributed to the rediscovery of ancient texts. Historians ascribe this revival to the Italian scholar Francesco Petrarca.

Francesco Petrarca, commonly known as Petrarch, is important to the Renaissance in more ways than one.

Petrarch discovered letters of the Roman scholar, Cicero, in which he found ancient philosophies founded on logic and reason. This prompted other scholars around Italy, and Europe as a whole, to seek out more ancient texts. Petrarch also came to be known as the Father of Humanism, a philosophy that places importance on man, rather than divine power, controlling his fate. Humanism became a defining characteristic of the Renaissance.

Other defining features include the mastery of perspective and the naturalist art movement.

During the Renaissance, art and science merged which allowed artists to use mathematics to master linear perspective. This allowed them to create more 3D images, something never explored in art before. This led artists to try to render the most realistic images and sculptures they possibly could, an art movement now known as Naturalism.

Renaissance art is often divided into three phases: Early Renaissance, High Renaissance, and Late Renaissance. Although vastly similar, there are some distinguishing factors between these three phases. During the Early Renaissance Florence, which was at this time an independent city-state, was the epicenter of art in Italy. This was largely due to the increased art patronage of the Catholic Church and the Medici family in the area. Large amounts of money were spent, particularly on sculptures, to decorate the city. Greek and Roman mythology were favorite themes of Early Renaissance sculptors.

The High Renaissance is known to be the peak of the movement.

During this phase, Italian Renaissance sculpture had spread to other major cities in Italy, most notably Rome. The masters of Renaissance sculpture, most famously Michelangelo, were commissioned by the Catholic Church to produce sculptures for St Peter’s Basilica and other sacred cathedrals. For this reason, the High Renaissance saw a decrease in themes of Greek and Roman mythology and an increase in themes of Christianity.

The Late Renaissance is more clearly different from the two previous phases thanks to the spread of Mannerism. The sculptures of the High Renaissance exhibited harmony, thought, and realism. In contrast, the Mannerism of the Late Renaissance was characterized by tension, emotion, and exaggeration. It was thought that the sculptors of the Late Renaissance did not believe they could exceed the work of their predecessors and thus had to do something different.

The Mannerism seen in the Late Renaissance is often considered to segue into the Baroque period.

The 10 Most Famous Renaissance Sculptures to Exist

Some of the most skillfully executed sculptures in history were created by Renaissance sculptors. Their understanding of human anatomy and how to work their chosen medium is unmatched. Famous Renaissance sculptures have become religious icons as well as tourist attractions that have captivated people from all walks of life.

Gates of Paradise (c. 1425 – 1452) by Lorenzo Ghiberti

| Year of Production | c. 1425-1452 |

| Medium | Gilded bronze |

| Dimensions | 473 cm x 767.5 cm |

| Current Location | Muse dell ‘Opera del Cuomo, Florence, Italy |

Ghiberti is often thought to have created one of the earliest sculptures of the Renaissance. In 1403, the Catholic Church held a competition for who would get commissioned to sculpt the doors for Florence’s Baptistery. Ghiberti won the trial with a door consisting of 28 bronze panels each depicting a different biblical theme.

This took him 21 years to complete.

In 1425, Ghiberti set to work on the doors for the eastern entrance of the Baptistery. In order to complete this commission, he set up a workshop in Florence that would train the likes of Donatello and other famous Renaissance sculptors. Even with the help of his apprentices, the doors would take a total of 27 years to complete.

The Gates of Paradise is made up of 10 bronze panels that have been gilded with gold. They portrayed various people featured in the Old Testament, such as Adam and Eve, Noah, Joseph, and other important biblical figures. Each of these panels was framed with ornate vegetation, statuettes of prophets, and busts of the artist and his father.

The famous Renaissance sculptor, Michelangelo, is actually the one who named this incredible piece of Renaissance art. Upon seeing them, he remarked that they looked like the “Porta del Paradiso”, or “The Gates of Paradise”. Until Michelangelo gave them this nickname, they were simply known as the East Doors.

David (c. 1430 – 1440) by Donatello

| Year of Production | c. 1430-1440 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions | 51 cm x 158 cm |

| Current Location | Muse Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy |

David by Donatello is one of the most influential sculptures of the Renaissance. Created somewhere between the years 1430 to 1440, it was commissioned by the Medici family for their courtyard. However, it was later relocated to the Palazzo Vecchio during one of the many exiles of the Medici from Florence.

Donatello first trained as a goldsmith and later in Ghiberti’s famous workshop in Florence. It is here that he learned to manipulate metals with such precision. In later years, Donatello would move to Rome to study Roman art and architecture.

During the Early Renaissance, themes of ancient Rome and Greece were very prominent in Renaissance art, as can be seen in many of the works of Donatello.

There are two main features that made Donatello’s David one of the most famous Renaissance sculptures. It was one of the first freestanding nudes created since the Classical period. During this time sculptures were almost always incorporated into the architecture of the place they were designed for.

This alone made this statue of David a revolutionary sculpture of the Renaissance.

Another thing that made David so unique was the techniques of naturalism used by Donatello to create the sculpture. Not only was it very proportionate, but it was also one of the more accurate Italian Renaissance sculptures of the biblical figure David. In the Bible, David is just a young boy when he defeats the giant Goliath. This is to demonstrate that even the weak can overcome the strong with God on their side. Donatello shows this through his almost effeminate portrayal of David. A laurel, the Roman symbol of victory, can also be seen on the sculpture’s head to signify his triumph.

Judith and Holofernes (c. 1455 – 1460) by Donatello

| Year of Production | c. 1455-1460 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions | 236 cm |

| Current Location | Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, Italy |

Judith and Holofernes, created circa 1455, was another one of Donatello’s famous Renaissance sculptures. Commissioned by the Medici it was meant to accompany David. Although, unlike David, Judith and Holofernes was once gilded, as can be seen by the remaining gold on Judith’s sword. The sculpture also originally displayed the inscription, “Kingdoms fall through sin, cities rise through virtues. Behold the neck of pride severed by the hand of humility.” However, this was later removed by the Republic due to its associations with the Medici.

The sculpture shows the tale of Judith, a Jewish widow, and Holofernes, the cruel commander of the Assyrian army. Holofernes planned to destroy the city in which Judith lived. In order to save her people, she seduces and beheads him while he is distracted. Like Donatello’s David this sculpture illustrates that even the weak can triumph over their foes when they are doing God’s work.

It is believed that Donatello showed the moment before the beheading to convey Judith’s moral struggle between breaking one of the 10 commandments and saving her city.

Judith and Holofernes was one of the first Italian Renaissance sculptures to be created “in the round”. This meant that it was supposed to be viewed from all angles with no clear front view. This technique later became very popular amongst Renaissance sculptors. Judith and Holofernes is also the only one of Donatello’s sculptures that he signed. It is thought that this is because it was one of his final creations and thus, he wanted to immortalize himself through his artwork.

It is noted by art historians that, although there is a large amount of literature from the Renaissance about Donatello’s artworks, there is very little about the artist himself. Many believe this is because he was not well-liked for a number of reasons.

Firstly, it was believed that he was ill-tempered and preferred to keep to himself. Secondly, he was said to be openly homosexual, something that was not acceptable at the time. Lastly, and most importantly, he was a close friend of the Medici family, who were hated by the people of Florence for being tyrants.

Pietà (c. 1498 – 1499) by Michelangelo

| Year of Production | c. 1498-1499 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions | 174 cm x 195 cm |

| Current Location | St Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City |

Pietà by Michelangelo was commissioned by Jean de Bilhères, a French cardinal based in Rome, to adorn his tomb. Michelangelo completed the Pietà in around 1498, at which stage he was in his early twenties. Whilst the sculpture decorated the cardinal’s burial place for over 200 years, it was later moved to St Peter’s Basilica, in Vatican City.

The Pietà depicts the Virgin Mary holding the body of Christ in her lap after he has been crucified. Michelangelo has been praised for the accuracy of his human forms and his attention to detail, especially when it comes to sculpting fabrics. He is also able to convey, as well as elicit, intense emotion through his artworks.

While this is one of Michelangelo’s first major sculptures, he already displayed the skills of a master of Italian Renaissance sculpture.

Although the Pietà is widely considered to be a masterpiece, it still received some criticism. This is mainly regarding the Virgin Mary, who appears much too young to have a middle-aged son. Michelangelo was a deeply religious man and so he had a great admiration for the Virgin Mary. He stated that he intentionally sculpted her to look so young in order to express her purity and saintliness.

The Pietà is the only one of his sculptures that Michelangelo ever signed. It is believed that he overheard onlookers discussing the beauty of the Pietà, however, they were giving credit for the sculpture to an artist from another region.

Out of frustration, Michelangelo then carved his name across the chest of the Virgin Mary. He later regretted this decision for being too vain and never signed another one of his artworks.

David (c. 1501 – 1504) by Michelangelo

| Year of Production | c. 1501-1504 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions | 517 cm x 199 cm |

| Current Location | Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy |

David by Michelangelo is by far the most famous Renaissance sculpture. It was created sometime between 1501 and 1504 out of pristine white marble. Although it was commissioned for the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, it is now housed in the Galleria dell’Accademia. However, in later years a replica of the statue was created for the Piazza della Signoria so that all members of the public could see it.

It is believed that Michelangelo based his David on the Greco-Roman hero Hercules. These Classical era influences are very common in Italian Renaissance sculpture. David is reminiscent of the nudes of antiquity, showing him as a perfect male specimen. However, when looking at the sculpture closely it can be seen that he is slightly cross-eyed. Art historians have said that this slight imperfection was intentional.

The flaw is supposedly out of respect to the sculptors of the Classical period to show that Michelangelo was not trying to one-up them.

Unlike most depictions of David in Renaissance art, Michelangelo’s David is not accompanied by the head of Goliath. Instead, he shows David in the moments before his fight with Goliath. David has a look of focus and determination on his face to show that he is ready for battle. A small catapult is slung over his shoulder, illustrating the theme of strategy over strength.

During the Renaissance, Florence was a republic. However, its freedom was frequently threatened by the oligarchical Medici family and other powerful Italian states. It is for this reason that the biblical hero David came to be a symbol of Florence and its battle with tyrants.

When Michelangelo’s statue of David was still situated in the Piazza della Signoria, he was positioned with his stare fixed on Rome, as a warning not to cause conflict with Florence.

Madonna of Bruges (c. 1501 – 1504) by Michelangelo

| Year of Production | c.1501-1504 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions | 200 cm |

| Current Location | Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk, Burges, Belgium |

Michelangelo completed Madonna of Bruges circa 1501. The sculpture was commissioned by a wealthy Flemish wool merchant to be placed in his family chapel. It is therefore the only one of Michelangelo’s sculptures to have left Italy during his lifetime. It remains in Belgium in Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk.

Madonna of Bruges is an unusual portrayal of the archetypal Mother and Child. Usually, the Virgin Mary is shown gazing down lovingly at baby Jesus. However, in the Madonna of Bruges Mary can be seen staring at the floor, away from her child. She is also barely holding baby Jesus, who looks as though he is about to walk off on his own.

It is believed that Mary’s solemn expression shows that she has an inkling about her son’s fate.

Typical depictions present a smiling, cherub-like baby Jesus. However, the baby Jesus in the Madonna of Bruges looks just as stony-faced as the Virgin Mary. This is once again to show that he is aware of his fate. The way he stands without much help from Mary shows that he will one day become a leader.

“Madonna of Bruges” has a very convoluted history, having been stolen from the Belgians twice.

In 1794, the famous Renaissance sculpture was stolen by French revolutionaries, who seized the area and took Madonna of Bruges back with them to Paris. It remained in Paris until 1816, after Napoleon was exiled. It was then stolen again in 1944, during World War II by Nazis who secretly transported it in a Red Cross van. Luckily, it was found and returned to Belgium two years later following the end of the war.

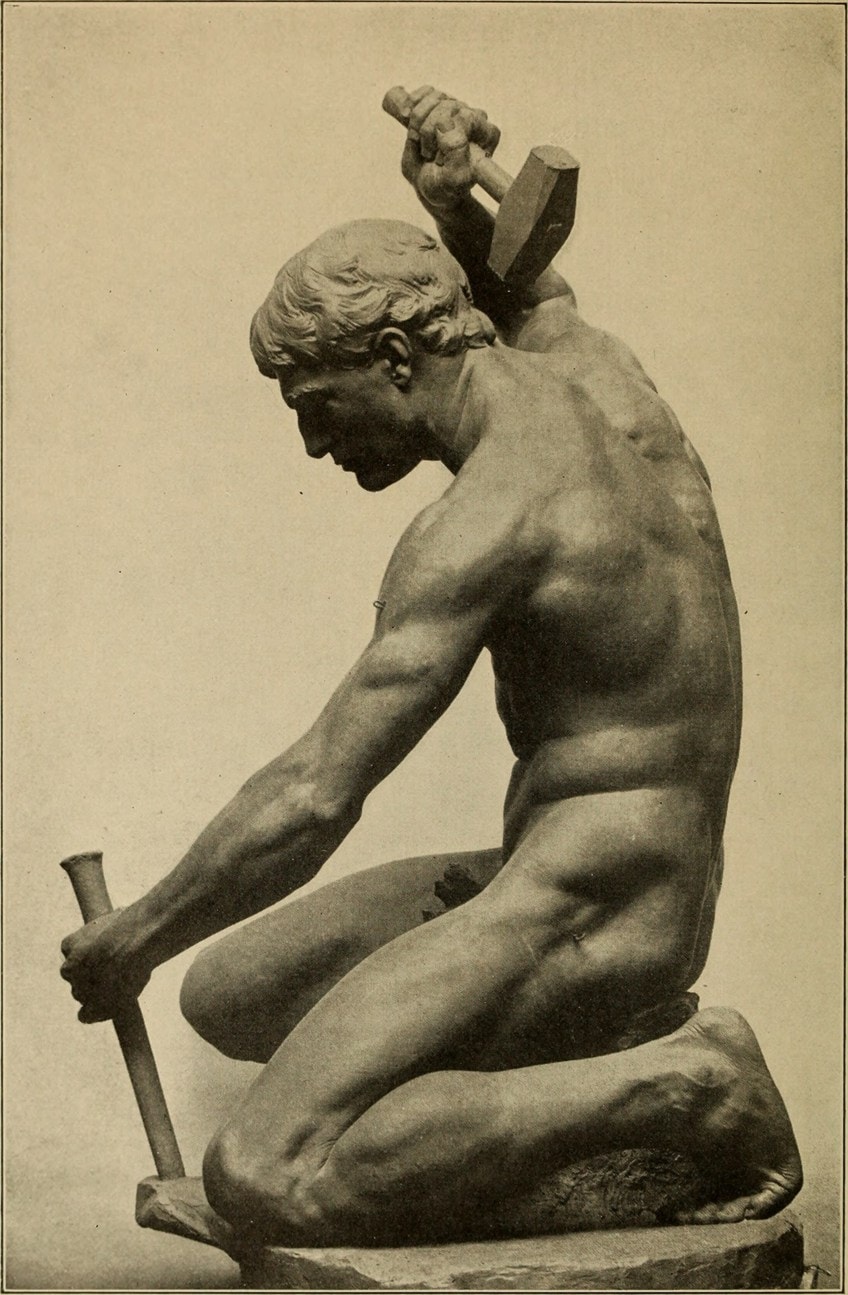

Hercules and Cacus (c. 1525 – 1534) by Bartolommeo Bandinelli

| Year of Production | c. 1525-1534 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions | 505 cm |

| Current Location | Piazza della Signoria, Florence, Italy |

The Italian Renaissance sculpture Hercules and Cacus was completed by Bartolomeo Bandinelli in around 1534. The story of how the sculpture came to be in existence is a very tumultuous one, heavily affected by the political instability at the time. It is also likely the reason why the sculpture did not receive the praise it does today during the Renaissance period.

The project was originally commissioned in 1507 by the Florentine republican council under Piero Soderini. The commission was first given to Michelangelo and was intended to accompany his David. The sculpture was to celebrate the removal of the Medici, a family of oligarchs, from Florence in 1494. However, Pope Julius II was keeping Michelangelo busy with various projects in the Vatican, such as painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Although Michelangelo preferred sculpting over painting, he felt that he could not say no to a pope due to his religious beliefs.

In the same year as the republic council commissioned the sculpture, they had a block of Carrara marble quarried for the project. However, in 1512 with the help of the Catholic Church and Spanish troops, the Medicis returned to control Florence. During all this political instability the block of marble had been forgotten. When it was rediscovered in 1523, Giulio de’ Medici ordered Bandinelli to take it and create a sculpture to symbolize the Medicis conquering their foes.

However, in 1527 the Medicis were exiled once again and the marble was handed, half-completed, to Michelangelo.

Before Michelangelo could even start on the commission, the Medici family returned to Florence for the final time in 1530. The marble was given back to Bandinelli by the Medicis. He chose the Roman myth of Hercules and Cacus as his subject for the sculpture. The myth is about the monster Cacus, who steals cattle from Hercules. Hercules, the hero of Roman mythology, then kills the monster. Hercules and Cacus came to symbolize the Medici stealing Florence’s civil liberties. For this reason, it was highly criticized during its time.

Perseus with the Head of Medusa (c. 1545 – 1554) by Benvenuto Cellini

| Year of Production | c. 1545-1554 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions | 24.5 cm x 71.5 cm |

| Current Location | Muse Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy |

Perseus with the Head of Medusa was created circa 1545 by the famous Renaissance sculptor Benvenuto Cellini. Cellini was originally trained as a goldsmith and the bronze Perseus with the Head of Medusa is a testament to his incredible ability to work metal.

The sculpture has been noted as one of the most exemplary examples of Mannerism from the Late Renaissance.

Like many of the famous Renaissance sculptures, Perseus with the Head of Medusa was commissioned by the Medici family. Cellini decided to use a technique to create Perseus with the Head of Medusa that was not typical of the time. He formed a singular cast with which he would mold the bronze. This once again displayed his incredible skills as an artist, as this was not an easy feat.

Perseus with the Head of Medusa portrays one of the most well-known stories in Greek mythology. In the myth, Perseus manages to avoid being turned to stone by Medusa’s gaze by looking at her reflection in his shield. Cellini referenced this in Perseus with the Head of Medusa by sculpting his own reflection onto the back of Perseus’s helmet. The myth ends with Perseus cutting off Medusa’s head while she is sleeping.

Cellini made the base of his sculpture part of the sculpture, something quite unique at the time.

The slain body of Medusa has been used as the base that Perseus stands upon. Cellini also used the base as an opportunity to convey a subtle political message. Snakes crawl out of the Gorgon’s body, representing the Medici taking over the city of Florence and threatening their democracy.

The Deposition (c. 1547 – 1555) by Michelangelo

| Year of Production | c. 1547-1555 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions | 277 cm |

| Current Location | Muse dell ‘Opera del Cuomo, Florence, Italy |

Michelangelo began working on The Deposition somewhere around 1555 when he was in his early 70s. It is one of the last things he sculpted before he died and was not a commissioned work. For this reason, it is believed to have been intended to decorate his own tomb.

Due to its religious subject matter, it is sometimes referred to as the “Florentine Pietà”.

The Deposition was sculpted out of pure white marble and is made up of four figures. Christ, as he’s being removed from the cross, the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, and the priest that would embalm Christ, Nicodemus. Many art historians believe that the figure of Nicodemus was sculpted in a likeness of the artist himself.

It was said that Michelangelo often worked late into the night on The Deposition. One night he became frustrated and took a hammer to the sculpture, damaging it in several places. It is unclear what made him do this. Some say it was unhappiness with his work, whilst others believe it to be a struggle with his religious beliefs.

Whatever his reasons, Michelangelo never worked on it again, selling it in its damaged and half-completed state.

The Deposition was bought by Francesco Bandini, a rich Florentine businessman. He then commissioned Tiberio Calcagni, a former apprentice of Michelangelo, to complete the sculpture. Due to this change of artist, along with the damage Michelangelo had caused, there are many inconsistencies in the sculpture, such as Christ’s missing leg. The Deposition was eventually sold, now completed, to Cosimo de ‘Medici III who then showcased it in various museums around Florence.

Abduction of a Sabine Woman (c. 1579 – 1583) by Giambologna

| Year of Production | c. 1579-1583 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions | 410 cm |

| Current Location | Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence, Italy |

Abduction of a Sabine Woman was completed circa 1579 by the Flemish sculptor Giambologna. Giambologna trained in Antwerp as a young boy and then moved to Rome to study under the Italian masters.

His Mannerist style was particularly influential in the Baroque period, which would follow the Late Renaissance.

Abduction of a Sabine Woman, often is often called Rape of the Sabine Women. However, this is an incorrect translation of the Latin rapio, which actually means “to drag off”. The sculpture tells the Roman legend in which Romulus, one of the founders of Rome, kidnaps a number of Sabine women. He and his troops were in need of wives in order to help them populate the area. However, the local Sabine tribe would not allow the Romans to marry any of their women. Thus, they staged a religious festival as a guise to gather all the Sabine women so that they could steal them.

Abduction of a Sabine Woman is carved from a singular block of marble, something that requires immense skill. It was created in the round and its complex composition makes it an incredible artwork from all angles. It depicts three figures in motion: a Sabine woman, with outstretched arms, trying to flee, a Roman soldier, muscles rippling as he tries to capture her; and an older man, who some believe to be her father and others believe to be her husband.

The clear emotion and movement displayed by Giambologna are what make “Abduction of a Sabine Woman” such an important Mannerist artwork.

Abduction of a Sabine Woman, commissioned by the Medici family, was widely celebrated during the Late Renaissance. Under their patronage, the Medici banned Giambologna from leaving Florence. This was because they were worried that the monarchs of Spain and Austria would see his brilliant work and entice him to come work for them instead.

That concludes our list of famous Renaissance sculptures. We saw an evolution of skills and themes from the Early Renaissance, through the High Renaissance, to the Late Renaissance periods. The list of magnificent sculptures that came out of this period is so expansive. This is why it would be impossible to include all of the brilliant sculptures produced during this time in a singular blog post. If you enjoyed reading about these wondrous sculptures and their fascinating histories, we encourage you to explore further.

Take a look at our Renaissance sculptures webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Characteristics Define Renaissance Sculpture?

Renaissance sculpture typically uses Naturalism, which strives to make its subjects as realistic as possible using proportion and in-depth detailing. Almost always, the subject matter of the sculpture was inspired by Roman-Greco or Christian themes. Finally, during the Late Renaissance, many sculptures displayed Mannerism, an art movement that used complex forms and exaggerated poses.

How Did Michelangelo Carve His Sculptures?

Michelangelo was one of the greatest artists of the Renaissance, and even history as a whole. He usually carved his sculptures out of a singular block of marble using a technique called subtractive sculpting. When asked how he created such beautiful sculptures, he would often say that he was simply letting free what was already in the marble.

Emma completed her Bachelor’s Degree in International Studies at the University of Stellenbosch. She majored in French, Political Science, and History. She graduated cum laude with a Postgraduate Diploma in Intercultural Communication. However, with all of these diverse interests, she became confused about what occupation to pursue. While exploring career options Emma interned at a nonprofit organization as a social media manager and content creator. This confirmed what she had always known deep down, that writing was her true passion.

Growing up, Emma was exposed to the world of art at an early age thanks to her artist father. As she grew older her interests in art and history collided and she spent hours pouring over artists’ biographies and books about art movements. Primitivism, Art Nouveau, and Surrealism are some of her favorite art movements. By joining the Art in Context team, she has set foot on a career path that has allowed her to explore all of her interests in a creative and dynamic way.

Learn more about the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Emma, Littleton, “Famous Renaissance Sculptures – The Top Sculptures of the Renaissance.” Art in Context. May 17, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/famous-renaissance-sculptures/

Littleton, E. (2022, 17 May). Famous Renaissance Sculptures – The Top Sculptures of the Renaissance. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/famous-renaissance-sculptures/

Littleton, Emma. “Famous Renaissance Sculptures – The Top Sculptures of the Renaissance.” Art in Context, May 17, 2022. https://artincontext.org/famous-renaissance-sculptures/.