Lost City of Petra in Jordan – Deciphering the Lost City’s Secrets

Why is Petra called the “Lost City”, and where is Petra located? The rock city of Petra is located in Jordan and is known as the Lost City of Petra because it was uninhabited for around 500 years before being rediscovered in 1812. In this article, we shall find out everything there is to know about the Lost City of Petra in Jordan. Join us below, as we explore the Lost City of Petra’s architecture, Petra’s treasury, and answer questions such as, “Who built Petra?”.

Table of Contents

Exploring the Lost City of Petra in Jordan

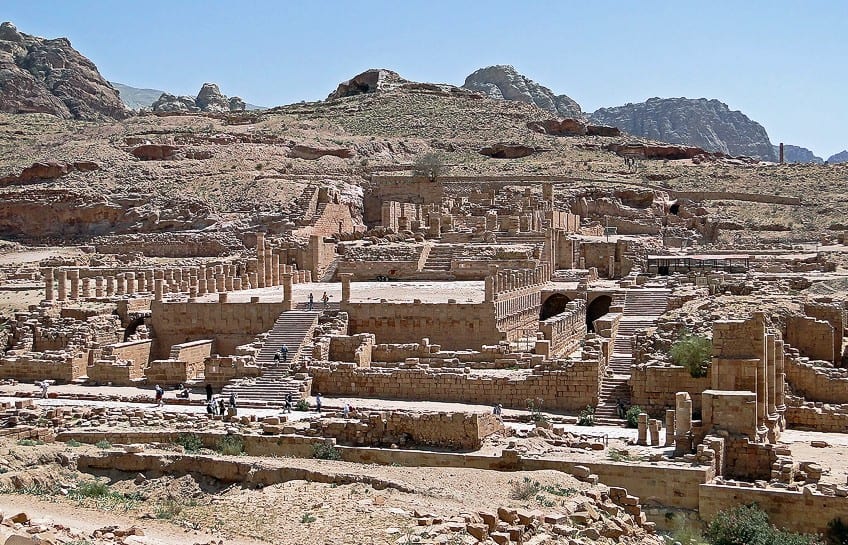

The rock city of Petra is an archaeological and historic city located in Jordan’s southern desert. It is located near to the Jabal Al-Madbah peak at the eastern flank of the Arabah valley, which extends from the Dead Sea to the Gulf of Aqaba, and is surrounded by mountains. The land surrounding the Lost City of Petra has been inhabited since around 7000 BCE, and the Nabataeans may have lived in what would eventually become their kingdom’s capital city as early as the 4th century BCE.

The only evidence of the Nabataean’s presence that has been discovered dates back to the 2nd century BCE, by which time Petra was already their capital. The Nabataean people were nomadic Arabs who established Petra as a significant regional economic center as a result of its close proximity to the incense trading routes.

The Nabataean Nomads

This trade provided the Nabataean people with a lot of money, and the Lost City of Petra in Jordan turned into the center of all their prosperity. The Nabataeans, unlike their adversaries, were used to living in harsh desert conditions and were able to withstand invasions by making use of the area’s rocky environment.

They were especially skilled in agriculture, rainwater harvesting, and stone sculpture. Petra prospered in the first century CE, when the Al-Khazneh edifice was built, thought to be Nabataean king Aretas IV’s mausoleum, and the city’s population peaked at approximately 20,000 people.

Even though the Nabataean kingdom had established itself as one of the Roman Empire’s client states in the 1st century BCE, it did not lose its independence until 106 CE.

Petra was conquered by the Romans, who changed the name of Nabataea to Arabia Petraea. Excavations have revealed that the Nabataeans’ capacity to regulate the water supply resulted in the construction of the arid metropolis, establishing an artificial oasis. Although the region is prone to flash floods, it appears that the Nabataeans used cisterns, dams, and water channels to control these floods. These technologies saved water during extended periods of drought, allowing the city to profit from its sale.

Description of the Lost City of Petra in Jordan

The rock city of Petra could be reached from the south via a trail that led through the plain of Petra, around the Jabal Haroun mountain, the site of the Tomb of Aaron, considered to be the location of Moses’ brother’s grave. Another possible access route was from the north’s high plateau.

The majority of today’s tourists approach the Lost City of Petra from the east. The stunning eastern entrance descends sharply down a narrow, dark valley called the Siq (meaning shaft), a natural geological formation produced by a substantial split in the sandstone rocks and functioning as a waterway pouring into Wadi Musa.

Hellenistic Petra Architecture

Petra is most renowned for its Hellenistic architecture. The façade of Petra’s tombs are depicted in the Hellenistic style, representing the diversity of cultures with which the Nabataens interacted, many of which were inspired by Greek culture.

The majority of these graves have relatively small burial niches cut into the stone. The Petra Treasury, which is 24 meters wide and 37 meters tall and resembles Alexandrian architecture, is arguably the greatest representation of the Hellenistic style.

The Petra Treasury’s exterior comprises a broken pediment with a central tholos within, as well as two obelisks that look like they’re formed into the rock at the top.

The twin Greek gods Pollux and Castor, who protect travelers on their trips, are located towards the bottom of the Petra Treasury. Two victories can also be observed towards the top of the Treasury, one on either side of a female figure.

This female figure is said to be the Tyche-Isis, the Greek and Egyptian deities of good fortune, respectively. The Monastery has a Nabataen influence while also embracing features of Greek architecture. Its only light source is its 8-meter-high entryway. A large area outside the Monastery has been specifically leveled for worshiping.

This was a location of Christian worship during the Byzantine era, but it is today a holy place for pilgrims to visit.

The City Center of the Rock City of Petra

Petra’s most ornate ruin, Al-Khazneh, is hewn into the sandstone rock at the very end of the Siq, the Arabic name for the narrow gorge. The face of the monument is scarred by countless bullet holes from the local Bedouin tribes who had hoped to take out all of the treasures that were originally thought to be hidden beneath it while still remaining in impressively preserved condition.

A little further away from the Petra Treasury, at the base of the mountain known as en-Nejr, is a vast theater strategically placed to provide the best view of the tombs. The theater and countless tombs were carved into the hillside during construction. One can still see rectangular gaps in the seats.

Rose-colored mountain cliffs almost completely encircle it on three sides, split into clusters by deep cracks and studded with knobs carved in the shape of towers.

The theater was designed to seat around 8,500 people. Poetry readings and plays were among the performances available to the public. Gladiator bouts were also believed to be staged here and generated the largest crowds, yet no gladiator was able to attain any recognition due to the high fatality rate.

The theater was one among numerous structures in Petra that suffered major damage as a result of the Galilee earthquake of 363 CE. Petra’s garden and pool complex is a group of buildings located in the city’s center.

Excavations at this location have enabled academics to classify it as an exquisite Nabataean garden, complete with a big swimming pool, an island pavilion, and an elaborate hydraulic system. In front of this complex is Colonnaded Street, one of the few Petra artifacts that were built rather than sculpted from the natural environment.

This street was home to Petra’s solitary tree and a semi-circular nymphaeum, which is presently in ruins because of flash floods. This was meant to represent the serene environment that the Nabataen people were able to create in the Lost City of Petra.

The colonnaded street was shortened to make space for a sidewalk after the Romans gained control of the rock city of Petra, and 72 columns were erected on each side.

Petra’s High Place of Sacrifice

Jebel Madbah Mountain is home to the High Place of Sacrifice. The trailhead is located near Petra’s theater. The High Place of Sacrifice is about an 800-step walk from there. The sacrifices that were performed there were usually thought to be libation.

Animal sacrifice was another prevalent kind of sacrifice practiced there, because of their belief that the grave of the Prophet Aaron is situated in the Lost City of Petra, which is a hallowed location for Muslims. Every year, a goat was slaughtered in honor of this. Other rites, like the burning of frankincense, were also performed there.

The Royal Tombs of Petra

The Royal Tombs of Petra exemplify Nabatean craftsmanship while also displaying Hellenistic design, yet the façades of Petra’s tombs have deteriorated because of natural degradation. One of these tombs, known as the Palace Tomb, is said to be the tomb of Petra’s rulers. The Corinthian Tomb, located next to the Palace Tomb, features the same Hellenistic style as the Petra Treasury. The Urn Tomb and the Silk Tomb are the other Royal Tombs at Petra.

The Urn Tomb has a wide garden in front and was converted into a church during the spread of Christianity in 446 CE.

The Exterior Platform of Petra

Archaeologists using satellite photos and drones uncovered a massive, previously undiscovered colossal edifice in 2016 whose origins were probably dated to around 150 BCE when the Nabataeans began their public construction project. It is situated just outside the city’s central area, at the base of Jabal an-Nmayr, and about 0.8 km south of the city center, however, it faces east, not west, and has no obvious tie to the city.

The structure itself is made up of a massive 184 by 56 by 49-meter platform with a massive stairway running down its eastern side. The enormous platform surrounded a somewhat smaller platform, which was topped by an 8.5 by 8.5-meter structure facing east toward the stairway. The edifice, which was second in scale only to the Monastery complex, most likely played a ceremonial role for which the experts have yet to provide even a hypothetical interpretation.

The History of the Lost City of Petra in Jordan

The Edomites occupied the Petra region throughout the Iron Age, which lasted from 1200 to 600 BCE. This occurred after King Solomon’s death which occurred in 928 BCE, when Israel was divided into two separate kingdoms, Judah to the south and Israel to the north.

The Edomites were referred to as Esau’s descendants, which was mentioned in the Bible’s Old Testament. The mountains of Petra were arranged in such a way that the Edomites were able to have a reservoir of water.

As a result, Petra became a popular stop for traders, rendering it an excellent trading location. Olive oil, wine, and timber were among the items traded here.

The Edomites were first joined by Nomads, who later fled, but the Edomites endured and left their mark on the rock city of Petra before the Nabataens arrived. They were eventually defeated by Juda’s King Amaziah and driven into their own territories.

Scholars disagree on whether or not 10,000 men were flung from the mountain of Umm el-Biyara. The Edomite settlement unearthed at the summit of the Umm el-Biyara mountain in Petra dates from the 7th century BCE.

The Emergence of the Lost City of Petra in Jordan

The Nabataeans were one of numerous nomadic Bedouin tribes that traversed the Arabian Desert, following their flocks to anywhere where grass and water could be found. Although the Nabataeans were first immersed in Aramaic culture, many modern-era academics dismiss suggestions that they had Aramean ancestors.

Linguistic, archaeological, and linguistic evidence, though, confirms that they are an Arabian tribe from the north. The Midianites inhabited this region during Moses’ time, according to Jewish historian Josephus, and it was governed by five kings, one of them being Rekem.

According to Josephus, the ancient city, known to the Greeks as Petra, “ranks foremost in the territory of the Arabs” and was still known as Rekeme by all Arabs of his day, in honor of its royal founder. Eusebius’ Onomasticon also recognized Rekem as being Petra. Raqama translates to “to decorate” in Arabic, therefore Rekeme might be a Nabataean phrase relating to the famed carved rock façades.

Workmen cleaning rubble from the rock near the gorge’s entrance discovered seven burial inscriptions in Nabatean script in 1964. One of them belonged to a man named Petraios, who was born in Rekem and ultimately buried in Jerash.

The Roman Period

When Cornelius Palma was Syria’s governor in 106 CE, the section of Arabia ruled by Petra was integrated into the Roman Empire as a part of Arabia Petraea, with the rock city of Petra as its capital. The local dynasty came to an end, although the city thrived under Roman administration.

This is the time when the Petra Roman Road was built. A hundred years later, under the reign of Alexander Severus, when this region was at its peak, the issue of currency was resolved. There was no more construction of lavish tombs, possibly due to some abrupt disaster, such as an invasion by neo-Persian might under the Sassanid Empire.

Meanwhile, Petra declined in significance as Palmyra expanded in and drew Arabian commerce away from it, yet, it appears to have survived as a religious center.

According to Epiphanius of Salamis, a feast took place on the 25th of December in honor of the virgin Khaabou and her son Dushara during his time. Al-Uzza and Dushara were two of the city’s principal deities, along with several idols of other Nabataean deities like Manat and Allat. Trajan constructed the Via Traiana Nova, which runs through Petra from the Red Sea to the Syrian border, between 111 and 114 CE.

This road followed the historic Nabataean caravan routes. This route reestablished commerce between Syria, Arabia, and Mediterranean ports under the shadow of the Pax Romana. Hadrian visited the old Nabataean capital in 130 CE, giving it the name Hadrin Petra Metropolis, which he engraved on his coins.

His visit, though, did not result in the same surge of construction and new structures as it did in Jerash. The governor of the region, Sextius Florentinus, created a huge mausoleum for his son towards the end of the al-Hubta tombs, which had previously been designated for the royal family during the Nabataean era.

The attention shown by Roman emperors in the city in the third century indicates that Petra and its surroundings were highly regarded for a long time. In the temple referred to as Qasr al-Bint, an inscription to Liber Pater, a divinity worshiped by Emperor Septimius Severus, was discovered, and Nabataean graves held silver coins with the emperor’s face, as well as ceramics from his reign.

Byzantine Period

Under Roman administration, Petra deteriorated significantly, primarily due to the remodeling of sea-based commerce routes. An earthquake in 363 CE damaged several structures and disrupted the critical water management infrastructure.

Petra was the seat of the Byzantine province of Palaestina III, and several Byzantine churches have been unearthed both in and around the area. In one Byzantine Church, 140 papyri were uncovered, mostly contracts dating from the 530s to the 590s CE, proving that the city was still thriving in the 6th century.

The Byzantine Church is a great example of Byzantine-era Petra’s monumental architecture.

The last mention of Byzantine-era Petra is in John Moschus’ Spiritual Meadow, published at the beginning of the 7th century. He tells a story about its Athenogenes, its bishop. It was no longer a metropolitan bishopric until 687 CE when the position was transferred to Areopolis. Petra does not appear in accounts of the Muslim invasion of the Levant, nor is it recorded in early Islamic chronicles.

Mamluks and Crusaders

The Crusaders erected fortifications, for example, the Alwaeira Castle in the 12th century but were compelled to depart Petra after a while. Because of this, the site of Petra remained unknown until the 19th century. There are two other Crusader-period castles in and near Petra: the first is al-Wu’ayra, which is located immediately north of Wadi Musa. It may be seen from the road leading to Little Petra.

It is the citadel that a group of Turks took control of with the aid of locals and that the Crusaders only recaptured once they started razing the Wadi Musa olive groves. The threat of losing their livelihood prompted the villagers to negotiate a capitulation.

The other is located on the peak of el-Habis in the center of Petra and is accessible from the western side of the Qasr al-Bint. During the medieval era, the remains of Petra piqued the interest of visitors, including Baibars, one of Egypt’s earliest Mamluk sultans, near the close of the 13th century.

19th and 20th Centuries

During his travels in 1812, Swiss traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt was the first European to describe the region. At the time, the Greek Church of Jerusalem had a diocese at Al Karak called Battra, and the Jerusalem clergy believed that Kerak was the Lost City of Petra in Jordan. The first accurately rendered sketches of Petra were done in 1828 by Louis-Maurice-Adolphe Linant de Bellefonds and Léon de Laborde.

David Roberts, a Scottish artist, visited Petra in 1839 and returned to England with images and accounts of his encounters with indigenous tribes. Frederic Edwin Church, a well-known American landscape painter who worked and lived in the 19th century, explored the Lost City of Petra in 1868; the resulting piece, El Khasné, Petra, is considered one of his most important and well-documented.

Archibald Forder, a missionary, released images of Petra in the National Geographic magazine, December 1909 issue.

Many of the tombs were exposed to robbers as the buildings crumbled with age, and many artifacts were taken. A four-person team comprised of British archaeologists George Horsfield and Agnes Conway, Palestinian folklore and physician specialist Dr. Tawfiq Canaan, and Danish academic Dr. Ditlef Nielsen explored and examined the rock city of Petra in 1929.

For over four decades, archaeologist Philip Hammond of the University of Utah explored the Lost City of Petra in Jordan. He said that local tradition maintains that it was formed by Moses’ wand striking the rocks so that it would bring forth life-giving water for the Israelites. According to Hammond, the ceramic pipes were used to build the channels deep under the earth, and the walls were formerly used to supply the city with water from rock-cut systems on the canyon rim.

In December 1993, many Greek scrolls dating from the Byzantine era were found in an unearthed church close to the Temple of the Winged Lions in Petra.

Religion

During the pre-Islamic era in this region, the Nabataean people worshiped Arab deities, in addition to several of their deified monarchs. Dushara was the main male deity, and he was accompanied by three feminine deities: Al-Uzza, Manat, and Allat.

These divinities are depicted in numerous rock carvings. New evidence suggests that Nabataean and Edomite religions had profound connections to Earth-Sun interactions, which were typically represented in the orientation of important Petra monuments to the equinox and solstice sunsets and sunrises. Petra has a stele dedicated to Qos-Allah. Qos is similar to the God of the earlier Edomites.

The seal from the Edomite Tawilan near Petra, which has been connected with Kaush, features a crescent and a star, both of which are compatible with a moon deity, and it is horned.

It is possible that the latter originated through commerce with Harran. The nature of Qos has been connected with both a rainbow (weather god) and a hunting bow (hunting deity). Some in the revisionist school of Islamic studies have recently proposed that Petra was once the original “Mecca” based on assertions of a large number of independent sources of evidence, specifically that the earlier original mosques faced Petra, not Mecca or Jerusalem, as the direction of the Qibla Muslim prayer).

Others, however, disagreed with the notion of comparing contemporary measurements of Qiblah directions with the interpretations of early mosques, asserting that early Muslims were unable to accurately determine the Qiblah’s direction to Mecca and that, as a result, Petra’s apparent pinpointing by some early mosques may simply be coincidental.

The Monastery, Petra’s most important structure, was built in the first century BC. It is devoted to Obodas I and is thought to be Obodas the god’s symposia. This information is engraved on the Monastery’s remains. The renowned Temple of the Winged Lions is a massive temple complex from King Aretas IV’s era.

The Temple of the Winged Lions on the northern bank and the Qasr al-Bint just across from it are two spectacular temples that can be seen in Petra’s Sacred Quarter, which is near the end of the city’s main Colonnaded Street.

Christianity arrived in Petra around the 4th century CE, about 500 years after the city was founded as a trading center. Rome’s very first Christian emperor, Constantine I, often known as Constantine The Great, took authority in 330 CE, which marked the beginning of Christianity in the rock city of Petra. Following the Islamic conquest, the Christian faith in the Lost City of Petra, as in the rest of Arabia, were forced to make way for Islam.

Problems Facing the Lost City of Petra in Jordan

The Petra site is threatened by a number of factors, including the collapse of historic structures, erosion caused by flooding and insufficient rainfall drainage, weathering caused by salt upwelling, incorrect repair of old structures, and excessive tourism.

The latter has grown significantly, particularly after the site garnered major media attention in 2007 with the New Seven Wonders of the World Internet and mobile campaign. The Petra National Trust was founded in an attempt to alleviate the concerns.

It has collaborated on initiatives with various international and local groups that encourage the protection, preservation, and conservation of the rock city of Petra.

In 2018, PETA produced a film documenting the mistreatment of worker animals in Petra. PETA said that every day, animals have to carry visitors or draw carriages. The footage showed personnel slapping and lashing the animals, with the beatings becoming more severe as the animals weakened. PETA also displayed other injured animals, including camels with open wounds infected with flies. The Jordanian government in charge of Petra replied by offering a veterinary facility and promising to educate animal keepers.

Conservation

The rock city of Petra is a unique cultural landscape formed by the junction of nature and cultural heritage. Since Johann Ludwig Burckhardt rediscovered the city in 1812, the cultural heritage site has drawn pilgrims, travelers, artists, and savants who are interested in the culture and history of the Nabataeans. However, archaeological scholars did not investigate the ruins in a systematic manner until the late 19th century.

Since then, frequent archaeological excavations and continuing studies on the Nabataean civilization have been a component of Petra’s UNESCO World Cultural Heritage status.

The digs in the Petra Archaeological Park have exposed a growing amount of Nabataean cultural heritage sites to environmental degradation. The management of water, which has an influence on the constructed heritage and the rock-hewn facades, is a key challenge. The huge number of findings and the exposure of buildings and artifacts necessitate conservation methods that respect the relationship between the cultural heritage and the natural landscape, which is especially important at the UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The breathtakingly gorgeous ancient rock city of Petra in southern Jordan is an international wonder like no other. The ancient rock city of Petra is carved into the pink-colored stone of Jabal Al-Madbah mountain, facing a valley. The Petra ruins, which date back to 9,000 BCE, provide incredible insight into the lives of people who once resided there. The city’s population was once significant enough that it grew to become the capital city of the Kingdom of Nabataea in the 4th century BCE. The ruins demonstrate the history of the local inhabitants, as well as the widespread impact of Greek architecture in past centuries.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Is Petra Called the Lost City?

Because of its advantageous location along ancient trade routes, the Lost City of Petra in Jordan grew into an affluent city famed for its innovative architecture, complex water management systems, and stunning rock-cut structures. However, when the Nabatean civilization declined, Petra vanished from memory and was eventually deserted. The site of the city was forgotten through time, and it was exclusively known to the nearby Bedouin tribe. The Lost City of Petra in Jordan did not grab the interest of the Western world until the early 19th century. Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, a Swiss adventurer, disguised himself as an Arab and invaded the region in 1812, finally uncovering the old city.

Where Is Petra Located and Who Built Petra?

The Lost City of Petra is situated in modern-day Jordan, in the country’s southwest region. It is located on a plain surrounded by mountains and is reached by a short ravine known as the Siq. The Nabatean people, an Arabic nomadic culture that developed in the 4th century BCE, founded and occupied the ancient city of Petra.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Lost City of Petra in Jordan – Deciphering the Lost City’s Secrets.” Art in Context. October 4, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/lost-city-of-petra-in-jordan/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 4 October). Lost City of Petra in Jordan – Deciphering the Lost City’s Secrets. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/lost-city-of-petra-in-jordan/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Lost City of Petra in Jordan – Deciphering the Lost City’s Secrets.” Art in Context, October 4, 2023. https://artincontext.org/lost-city-of-petra-in-jordan/.