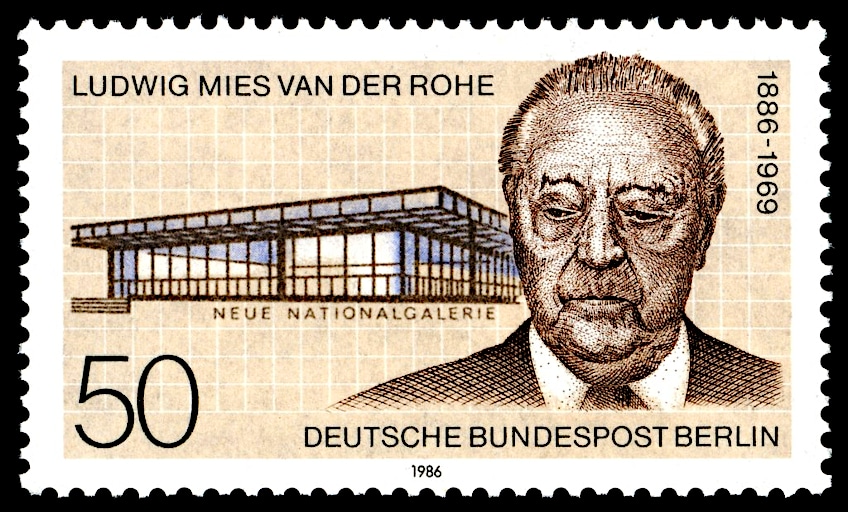

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe – Pioneer of Architectural Restraint

During the early 1920s, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe pioneered the development of the International Style, leading to it becoming the most important movement of modern architecture. Unlike Le Corbusier and other initial supporters of the style, who drifted apart from it in the 1960s, architect van der Rohe stayed entirely committed to the movement for the next 40 years of his career. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s buildings were primary targets for those in the postmodern movement who eventually denounced the International Style. They did not agree with his “less is more” ideology and wanted to make buildings more ornate, forgetting perhaps that he also insisted that “God is in the details”.

Table of Contents

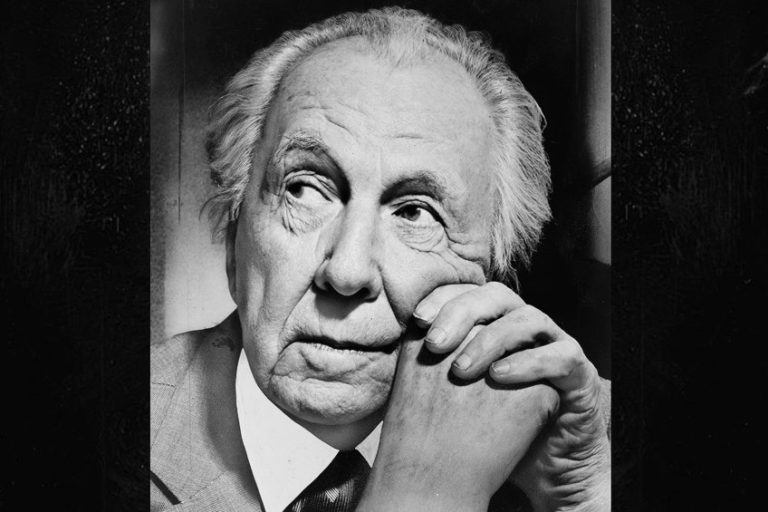

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Biography

| Nationality | German-American |

| Date of Birth | 27 March 1886 |

| Date of Death | 17 August 1969 |

| Place of Birth | Aachen, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire |

Architect van der Rohe’s plans for glass and steel towers, horizontally oriented dwellings, and pavilions were first dubbed “skin-and-bones” architecture because of its minimalist use of different materials, specificity of space, the rigidity of construction, and clarity.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s buildings encourage a connection between the internal and external spaces, as well as the abandonment of the sensation of being fully confined. Instead, they promote flexibility in their spatial arrangements, which meant maximum spatial efficiency for Mies.

Early Life and Education

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s father was a stonecutter, but besides accompanying him to construction sites, he never obtained traditional architectural instruction. Mies learned to draw at the age of 15 when he was assigned to several local Aachen architects to produce sketches for architectural embellishments. Mies relocated to Berlin in 1905, and within two years he obtained his first independent contract just outside Berlin.

When Germany’s most innovative architect, Peter Behrens, saw Mies’ work for the first time, he was so impressed that he gave Mies a job in his company.

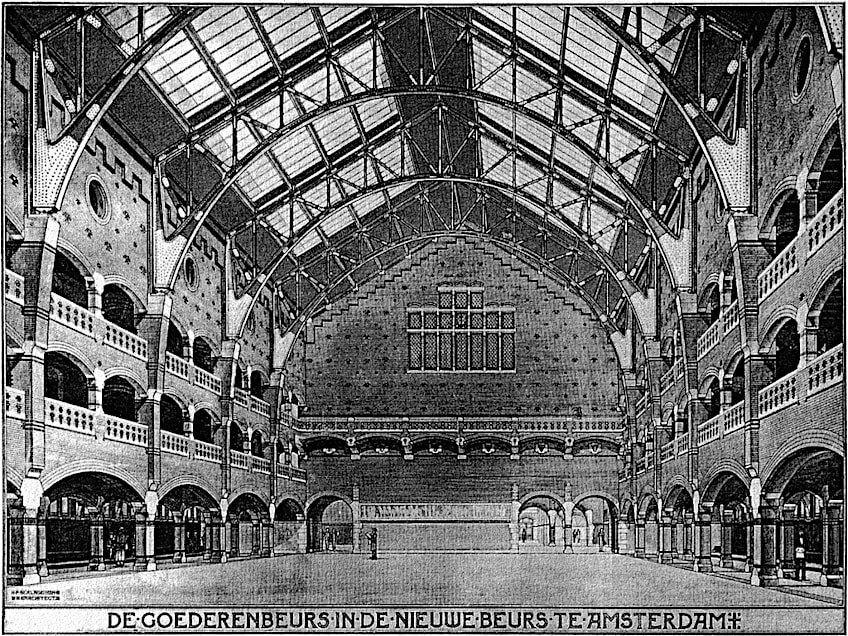

Working under Behrens, however, irritated Mies. Later, he claimed responsibility for the patio structures of Behrens’ huge turbine factory for AEG, erected between 1907 and 1910 in Berlin, claiming that Behrens “didn’t comprehend what he was producing.” Mies frequently professed his appreciation for Hendrik Petrus Berlage, the famed Dutch architect, and his Amsterdam Exchange, completed in 1903, a structure Behrens once described as “outdated.” Mies supposedly said, “Well, in this case, you are completely wrong,” which enraged Behrens, who was on the verge of attacking Mies.

The War Years

Mies was said to be quite a strong man with a commanding physique, but his disposition was reserved, quiet, and cautious. He married Adele Bruhn, the daughter of a rich entrepreneur, in 1913. In order to commemorate his transformation from artisan to architect, Mies changed his surname to include “Rohe,” which was his mother’s maiden name. According to most reports, his relationship with Ada was rife with issues, despite the fact that they had three children. One of them, Dorothea, rose to prominence as a dancer and then as an actor, particularly in New York. Another, Waltraud, went on to work as a researcher and curator at the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1915, Mies was recruited for World War I, first to Frankfurt-am-Main, then Berlin, and eventually to Romania in 1917, where he remained for the duration of the conflict and fathered a child.

Return to Architecture

Mies was discharged from the army in November 1918. He felt dissatisfied despite the fact that there were no financial problems, thanks to Ada’s father. Though he continued his work, he was having a professional crisis concerning the future of his architecture, and he and Ada divorced in February 1920. She took custody of their kids, whom Mies only saw on rare occasions until he emigrated to the United States. He stayed in Berlin while she and the daughters relocated to Bornstedt.

Mies spent most of the early 1920s moving around Berlin’s melting-pot culture of design and architecture ideas, connecting with Werner Graeff, Theo van Doesburg, and El Lissitzky, and keeping up with the advances of the de Stijl, Bauhaus, Expressionism, and Constructivism.

He supported his profession by accepting orders for private mansions for affluent clientele, which he designed in a conventional style. Simultaneously, his conceptual notions about architecture started to shift in new directions. By 1924, Mies had started to connect with Lily Reich, a home furnishings designer who also served as his office administrator until he relocated to the United States.

Mies organized a separate house for her, as he did with all the women he was connected with after his marriage failed. Reich was in charge of arranging and erecting an interior furnishings show in Stüttgart in 1927, which coincided with Mies’ creation of the Weissenhofsiedlung prototype dwelling display. Mies debuted his MR tubular steel chair for the exhibition, which was influenced by previous versions by Mart Stam and Marcel Breuer. Mies and Reich collaborated on the legendary Barcelona Chair (1929), perhaps the most well-known furniture creation of the century, which debuted at the 1929 World’s Fair within Mies’ Barcelona Pavilion.

The Effects of Nazi Germany

Mies had been richly compensated for his Barcelona Pavilion at the 1929 World’s Fair, and he earned a substantial salary when he decided to take over as Bauhaus Director in 1930 from Hannes Meyer, who had resigned amid criticism after the anti-leftist city administration of Dessau, where the college was then positioned, had accused him of Socialist political advocacy. Mies sought to depoliticize the atmosphere by disassociating the school from production in order to focus completely on educating students in architecture, art, and design. Mies individually assessed each pupil upon his arrival, eliminating any he thought disinterested or overly political. Apart from Lily Reich, he did not make too many changes to the faculty.

He started to look the part of the role he suddenly found himself in, always wearing suits with trendy bowler and homburg hats. He even sported a monocle for a short period. He gained some weight and became a near-constant cigar smoker, a habit that would eventually kill him numerous years later. Meanwhile, Mies’ naturally reserved nature grew as an instructor into a kind of “magisterial aloofness,” portraying the powerful, quiet type.

Indeed, one acquaintance remarked that Mies would frequently let others dominate a discussion until he felt they had said everything they intended to say, then would often slip in and make a sweeping declaration or interject something that no one had contemplated before, adding to the weight of his comments.

Mies took over the Bauhaus, but with the emergence of the Nazis and the persistent opposition in Dessau, it became evident that the school was vulnerable even after the transfer to Berlin in 1932. Mies put his own money into a derelict telephone building on Berlin’s outskirts as the institution’s new home, but it was confiscated by the Nazis. Mies and his fellow teachers shuttered the school on their own initiative after prolonged negotiations with Hitler’s subordinates to allow it to reopen, believing that it would not flourish in the new German political system.

Relocation to the United States

Despite his claimed a-politicism, Mies’ professional status in Nazi Germany had grown problematic by 1937. Mies eventually accepted an opportunity to lead the architectural department at the Armor Institute of Technology after negotiating with numerous colleges. Mies relocated permanently to the United States in August 1938, just in time for the beginning of the new academic year, after being interrogated by Nazi officials over his passport. During one of these conversations, Mies managed to contact Frank Lloyd Wright, who unexpectedly invited him to Taliesin, where the two connected regardless of the fact that Mies could not speak a word of English and Wright in return had no idea how to speak German.

Taliesin wowed Mies, who strolled out onto the balcony viewing the Wisconsin countryside and exclaimed, “Freedom! It’s a kingdom!”

When they arrived in Chicago, Wright also took Mies on a tour of Oak Park. Of course, once Mies had moved into his new house, Wright would famously expose him to the architectural world in Chicago. Mies settled in Chicago, learning English along the way. He encountered Lora Marx, a sculptress who had recently separated from Samuel Marx, the architect, on New Year’s Eve 1940. According to everyone there, it was true love, a romance that would remain until Mies’ passing, but they would never marry and never lived together. Mies would subsequently describe the years between 1941 and their short breakup as the “greatest years of his life.” Lora assisted Mies in finding permanent accommodation in downtown Chicago – hardly the contemporary structures he was creating.

Mies had the home mostly to himself until his daughters came to stay in the late 1940s. He also connected with his grandson, Dirk Lohan, through Marianne in the 1940s. Lohan would eventually learn under Mies and grow professionally and personally close to his grandfather, to the point that he was frequently called on when one of Mies’ structures needed renovation or an expansion was envisaged. Mies interacted regularly in Chicago, both with pupils and acquaintances, and most recall him as accessible despite his guarded demeanor, even going so far as to be regarded as a type of paternal figure to many of the younger men he supervised at IIT. Mies found it easy to manage the dual obligations of lecturing and professional activity, however as time passed, he became less interested in teaching.

Mies also enjoyed social drinking, especially martinis, and he could hold his booze. Lora couldn’t, ultimately confessing to herself that she was an alcoholic in 1947, joining Alcoholics Anonymous, and splitting up with Mies for a year. Mies’ pupils, employees, and even his chauffeur – Mies did not even possess a vehicle until the 1950s – hardly ever saw him intoxicated.

Mies also had the privilege of having a one-man show at MoMA in 1947, which was visited by Frank Lloyd Wright. The show’s popularity and exposure increased Mies’ global notoriety, and in the same year, he encountered a real-estate entrepreneur named Herbert Greenwald, who became one of Mies’ most devoted clients.

Greenwald would ask Mies to build the Lake Shore Drive Apartments in Chicago. Lafayette Park was a massive makeover of a degraded low-income neighborhood north of downtown that fell under the overarching concept of postwar American urban regeneration. Nevertheless, unlike many other urban renewal initiatives, Mies’ concept – a mixed-use proposal of townhouses, high rises, schools, industrial development, and completed in collaboration with Ludwig Hilberseimer – was reasonably successful. In the late 1950s, Lafayette Park became so crucial to Mies’ office’s functioning that when Greenwald passed, Mies was obliged to lay off half his staff, despite the fact that the construction was largely incomplete.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RpCYmJPICdA

Later Career and Death

Mies’ health deteriorated gradually after 1960. He was significantly less involved in the day-to-day activities of his business, but the company continued to grow, completing structures such as the Berlin Neuenationalgalerie, which opened in September 1968. Mies was too ill to make the dedication, although he had been present many months earlier when the vast coffered roof was constructed, a nine-hour event that he had observed with great enthusiasm. Mies was incapacitated by arthritis and spent a lot of time at home, but he accepted visitors on a daily basis, notably Dirk Lohan and Gene Summers from his office, Lora Marx, and his daughter Marianne.

He and Lora traveled a bit; one of their favorite destinations was Tucson, Arizona, which provided a welcome escape from the bitter Chicago winters. Mies developed wall-eye, making it impossible for him to focus on words on a piece of paper for long periods of time, so Lora took up the responsibility of reading to him. Mies’ first esophageal physical signs, caused by decades of smoking, occurred in 1966. His poor condition made surgery impossible, therefore he was treated with radiation. Mies had a cold in early August 1969, which quickly turned into pneumonia. He passed away after a couple of weeks of drifting in and out of consciousness.

Architect van der Rohe was the last of the International Style trinity to pass, after Le Corbusier in 1965 and Gropius only a few months before him. He is interred at Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery, among the tombs of architects Louis Sullivan and Daniel Burnham.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Legacy

By the time van der Rohe’s health began to deteriorate, the pushback against the International Style was in full force. Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966), Robert Venturi’s definitive attack on the stiffness of Miesian architecture, left little uncertainty about the focus of its critique. Venturi stated, “I prefer components that are hybrid instead of clean, and that compromise rather than appear pristine. I favor chaotic vibrancy over apparent unity.” Furthermore, he flipped Mies’ most well-known phrase, implying that “less is a bore.”

Yet, this was not the first shot fired against the corpus of modernist architecture; Paul Rudolph, Louis Kahn, and even Le Corbusier had started reconsidering the steel-and-glass style Mies had popularized in the 1950s.

The ferocity with which designers and reviewers of the 1960s reacted to the International Style’s dominance over design reflects, too, the unmatched grip that it – and notably Mies – had over the ideology of modernity in architecture in the postwar period.

Advancements in travel and communication have made the International Style a worldwide movement, with thousands of designers adopting it on every continent in the world. During the exact time that Mies’ architecture was being criticized, he was being critically lauded in different retrospectives and exhibits, notably one in 1968 at the Art Institute of Chicago.

The Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Archive was officially founded that same year at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and it currently houses over 19,000 of Mies’ prints and designs. Van der Rohe’s popularity has remained uninterrupted to the present day, with two exhibits focusing on the two sides of Mies’ career debuting in 2001: Mies in Berlin, and simultaneously, Mies in America. Both had elaborate exhibition booklets that contained comments by prominent academics. His designs, letters, and publications are housed in collections at the University of Illinois, the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago’s Newberry Library, the Library of Congress, as well as the Canadian Centre for Architecture. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe has received various honors, both during his lifetime and after his death.

Notable Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Buildings

While the Postmodernists found Mies van der Rohe’s buildings to be uninspiring and rigid, the majority of the world embraced the international style. Mies van der Rohe’s buildings frequently accentuate their particular uniqueness in relation to their environment, putting them – and, through their transparency, their occupants – on display. While several of them, for example, the Barcelona Pavilion, are perfect for public gatherings, others, such as the Farnsworth House, are infamously challenging to occupy when privacy is required.

Barcelona Pavilion (1929) – Barcelona, Spain

| Architect | Ludwig Mies van der Rohe |

| Date | 1929 |

| Medium | Steel frame with glass and polished stone |

| Location | Barcelona, Spain |

Mies created the Barcelona Pavilion for the 1929 World’s Fair in Spain, a building that is today regarded as one of the most noteworthy temporary buildings ever erected, especially for an international exposition. It is Mies van der Rohe’s most clear and precise statement regarding the simplification of a structure to the bare necessities of defining space: a few columns placed on a platform contrasted with asymmetrically placed transparent and opaque wall planes bearing a flat roof.

During the exposition, it served as a reception area for guests. The Pavilion’s construction represented the peak of Mies’ European career, and for many, the culmination of his entire output. It was, without a doubt, the most forward-thinking building erected during the exposition, standing in stark contrast to the more traditional neo-Baroque architecture that characterized the rest of the buildings exhibited.

Tugendhat House (1930) – Brno, Czech Republic

| Architect | Ludwig Mies van der Rohe |

| Date | 1930 |

| Medium | Steel-framed, glass, and concrete |

| Location | Brno, Czech Republic |

Mies’ previously completed residences had all been typical brick constructions, hence this is considered his first completely modern house. The Tugendhat House is an excellent illustration of how he utilized modern construction techniques to integrate a structure with its surroundings. Mies’ structure is exceptionally huge – considerably larger than the Tugendhat’s expected – and has a very open interior design, with few inner walls to hang things on.

Other contemporary features were advanced heating and air systems, which were a rare luxury at the time, particularly in Europe, and a glass wall on the inside of the home that could drop into the basement like a car’s window.

Farnsworth House (1951) – Plano, Illinois

| Architect | Ludwig Mies van der Rohe |

| Date | 1951 |

| Medium | Steel, concrete, natural stone, and glass |

| Location | Plano, Illinois |

The Farnsworth House, Mies’ iconic postwar home, is probably the pinnacle of minimalist domestic construction utilizing industrial materials. However, its architecture and history are significantly more interesting than the final product reveals. The house’s I-beams and concrete-slab frame are clearly visible, with a plain box covered on all four sides by curtain walls of glass. This method essentially blurs the line between the internal and external spaces, putting the occupants in continuous communication with nature.

Despite its flaws, this house with its glass walls allowing for the visual integration of the exterior within the interior, remains one of the most influential models for architects to this day.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s buildings have always been clean and simple, in fact, he is credited for coining the phrase “less is more”. There were detractors of his style, who felt that his architecture was cold and lifeless. However, when it first emerged on the international scene it was welcomed as a necessary change from the stuffy and claustrophobic brick structures that were predominant at the time.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Believed That Less Is More in Architecture?

Architect van de Rohe is credited with creating the phrase. He was tired of architecture that was unnecessarily complicated and closed-in. He wanted to create structures that integrated with their surroundings and blurred the lines between the interior and exterior spaces. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s buildings are known for being open, transparent, and uncluttered.

What Was Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Known For?

Van der Rohe was very specific about the materials that he utilized, incorporating bronze, chrome, glass, steel, and fine stone into his designs. This meant that his structures were both finely crafted and costly to build. His work on the Barcelona Pavilion drew worldwide acclaim and set the standard for a new architectural style globally. Its adoption was so widespread that it became known as the International Style. However, many subsequent architects would eschew this style in favor of less rigid aesthetics.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Ludwig Mies van der Rohe – Pioneer of Architectural Restraint.” Art in Context. January 4, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/ludwig-mies-van-der-rohe/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 4 January). Ludwig Mies van der Rohe – Pioneer of Architectural Restraint. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/ludwig-mies-van-der-rohe/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Ludwig Mies van der Rohe – Pioneer of Architectural Restraint.” Art in Context, January 4, 2023. https://artincontext.org/ludwig-mies-van-der-rohe/.