Antoni Gaudí – An Exploration of the Life of This Spanish Architect

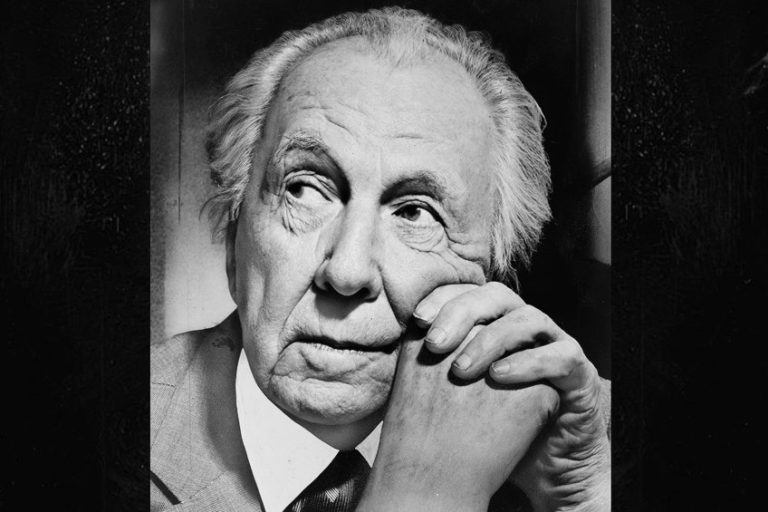

Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí is regarded as the most renowned member of Catalan Modernism. Gaudí’s architecture is highly regarded for its unique and individualized style. Many of Antoni Gaudí’s buildings can be found in the city of Barcelona, including his notable contributions to Spanish architecture such as the Sagrada Familia Church. Gaudí’s art was motivated by his three major life passions: God, nature, and architecture.

Table of Contents

Antoni Gaudí’s Biography

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Date of Birth | 25 June 1852 |

| Date of Death | 10 June 1926 |

| Place of Birth | Catalonia, Spain |

| Occupation | Architect |

Gaudí’s architecture transcended the Modernista movement that he was originally a part of, which culminated in a style that was influenced by the organic forms of nature. Antoni Gaudí’s buildings were very rarely designed from sketches, but rather from scale models.

Gaudí’s art is appreciated throughout the globe by architects who still study his methods and style to the present day.

Childhood

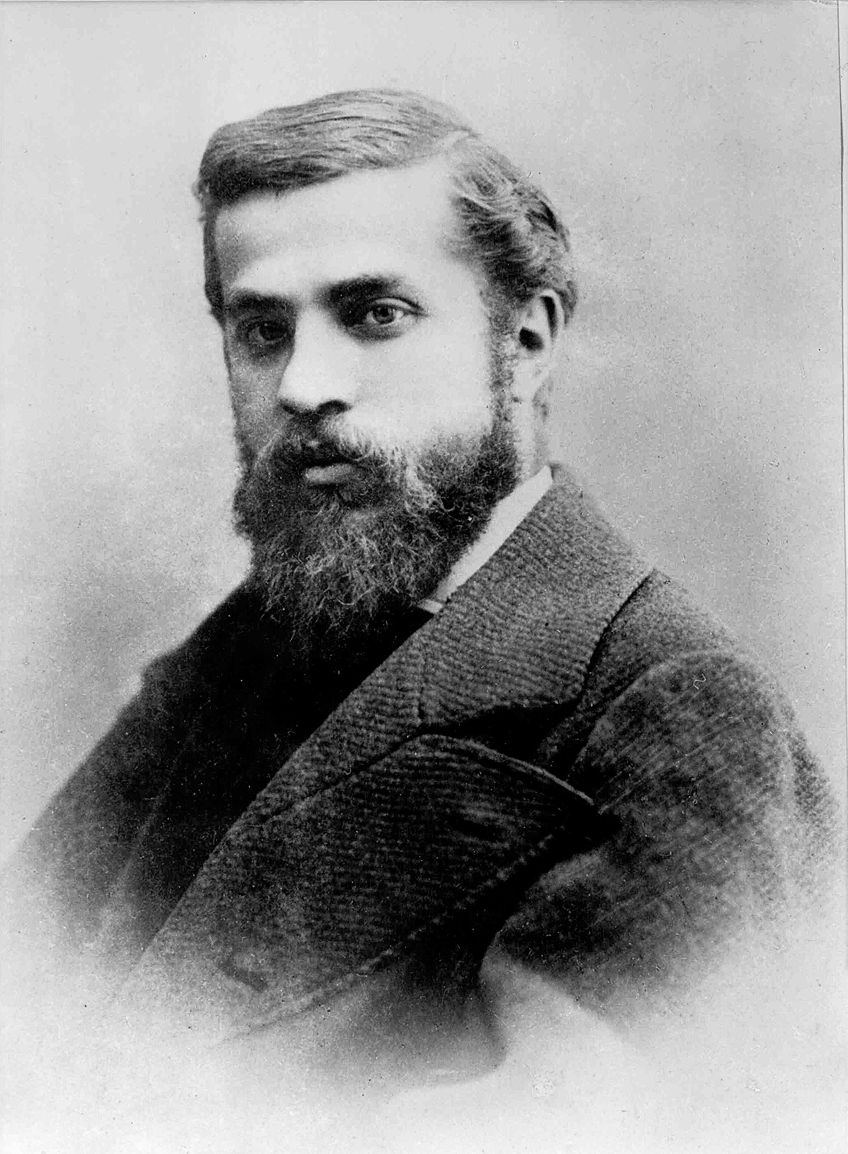

Antoni Gaudí was born in June 1852 on the Mediterranean coast in Reus, Catalonia, south of Barcelona. The original location of his birth is the subject of some debate, as accurate documentation is lacking, and it is sometimes asserted that he was born in Riudoms, the home village of his father’s family. Gaudí’s ancestors were from the Auvergne area of southern France.

Gaudí always had a strong affinity for nature, particularly the landscape of his home Catalonia.

He finally became an avid outdoor lover, attending the Centre Excursionista de Catalunya in 1879. Despite his enthusiasm for the outdoors, Gaudí was unwell as a child, suffering from a variety of maladies, particularly rheumatism, which appear to have added to his reserved demeanor.

Education

Gaudí spent most of his childhood in Reus, where he went to nursery school with Francesc Berenguer, who would one day become one of his helpers, and was employed in a textile mill. He came to Barcelona in 1868 to study instruction at a monastery. While there, he grew interested in idealistic socialist principles, and he devised a proposal with two of his fellow classmates to convert the Poblet Monastery into a utopian community, an experimental facility envisioned by Charles Fourier and other thinkers of the time.

Gaudí served four years of obligatory military duty beginning in 1875, but due to ill health, he expended much of his time on medical leave, allowing him to register in the Llotja School and subsequently the Barcelona Higher School of Architecture, wherein 1878, he finished with a degree in architecture.

Health issues appear to have been prevalent in Gaudí’s family at the period, since his mother died in 1876, as did Francesc, his older brother who had recently become a doctor. Nevertheless, Gaudí, as a young man, swiftly learned the fundamentals and made the contacts that would push him to succeed in life. He worked as a draftsman for several of Barcelona’s most prominent architects, notably Josep Fontserè, Joan Martorell, and Leandre Serrallach, to help pay for his education.

During this period, Gaudí created one of the few surviving handwritten papers traceable to him: the “Reus Manuscript,” which was essentially a student notebook in which Gaudí chronicled his views of architecture and interior décor, as well as his early opinions on these subjects.

Independent Studio

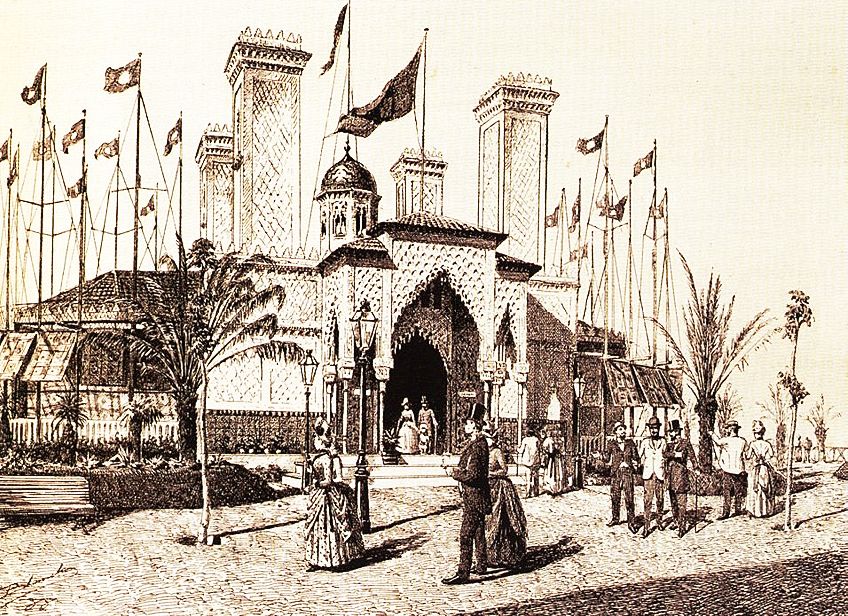

Gaudí began to amass his own clientele even before graduating in 1878. That same year, he created an exhibition for the glove producer Camella at the World’s Fair in Paris, which piqued the interest of textile distributor Eusebi Güell, who immediately commissioned Gaudí to create the furniture for the Palacio de Sobrellano in Comillas.

Over the next 35 years, Eusebi Güell would commission Gaudí for no less than five large developments.

The Casa Vicens, a mansion for Manuel Vicens I Montaner, a Catalan brick and ceramic producer, was Gaudí’s first big contract in 1877, and it essentially solidified Gaudí’s name in Barcelona. Gaudí began construction on the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona in 1883, the very year the Casa Vicens was finished. Gaudí got drawn to Josefa Moreu, a schoolteacher there, through a contract in 1878, but she did not return his sentiments.

She was the only lady in Gaudí’s life for whom he displayed love interest, and after the rebuff, he immersed himself in his work for the remainder of his life, his Catholic faith establishing an ever-greater grasp over his brain.

In 1885, he temporarily relocated to the remote village of Sant Feliu de Codines to avoid a cholera epidemic, residing at Francesc Ullar’s home. Gaudí, appreciative of the emergency shelter, constructed a supper table in exchange for the shelter. The 1888 World’s Fair attracted attention to Barcelona, and the city got significant upgrades, including the extension of electricity supply, which was conspicuously shown at nighttime by archways of lights that stretched the breadth of the city’s principal boulevards.

Gaudí was commissioned to build the pavilion for the Compañia Transatlántica, a shipping concern controlled by the Marquis of Comillas, which was renowned for its use of semicircular arches. This resulted in a few repair contracts for Gaudí from the Barcelona city government.

The Güell Family

Gaudí acquired the majority of his key assignments from Eusebi Güell. The two men shared many traits, especially their ardent Catholicism. These commenced in 1884 with the plans for the Güell Pavilions, extensions for Güell’s summer residence at Pedralbes, Catalonia, continuing with Gaudí’s efforts on the Palau Güell, the residence in central Barcelona, which is now accessible for public visits.

In 1890, Güell relocated his factory to Santa Coloma de Cervelló and commissioned Gaudí to construct a village for his workers. Gaudí worked on the assignment for approximately 30 years before it was abandoned by Güell’s heirs in 1918.

Güell was one of Gaudí’s most notable acquaintances who described him positively as a friendly individual to chat to, as well as courteous and loyal to his close companions. This greatly contradicted other stories that portrayed Gaudí as harsh, distant, and anti-social.

Gaudí played the role of a socialite initially in his career, purportedly dressed in expensive outfits and regular social gatherings such as the opera, theater, satisfying a passion for gourmet cuisine (supposedly, notwithstanding his vegetarian diet), and appearing at job sites in a horse-drawn carriage. This changed radically over time, as his beliefs compelled him to adopt a considerably more austere way of life.

Yet, it is worth mentioning that Gaudí had a considerably broader clientele than only the Güell family; he also created several private residences, residential blocks, industrial and commercial buildings, and a vast number of church-related orders, including many restorations.

In 1908, Gaudí was even commissioned by two American capitalists whose identities are unknown to this day to build the Hotel Attraction, a skyscraper in New York marked by a parabolic center tower meant to be higher than the Empire State Building, and capped by a star pattern.

The Nationalism of Catalonia

Considering his recurrent use of Catalan elements in his structures, which reveal his profound attachment to his own area, Gaudí was rarely personally involved in political activity. He kept in touch with provincial artist associations, such as the Catholic Artistic Circle of St. Luke, which he joined in 1899. Despite pressure from acquaintances and friends, he declined to run for politics, as a handful of his fellow Modernisme architects had. Gaudí did, however, take part in protests.

In 1920, he was attacked by police during a riot in Barcelona, and on Catalonia’s National Day, Gaudí was assaulted and detained during a demonstration against tyrant Primo de Rivera’s prohibition on the use of the Catalan tongue.

Last Years and Death

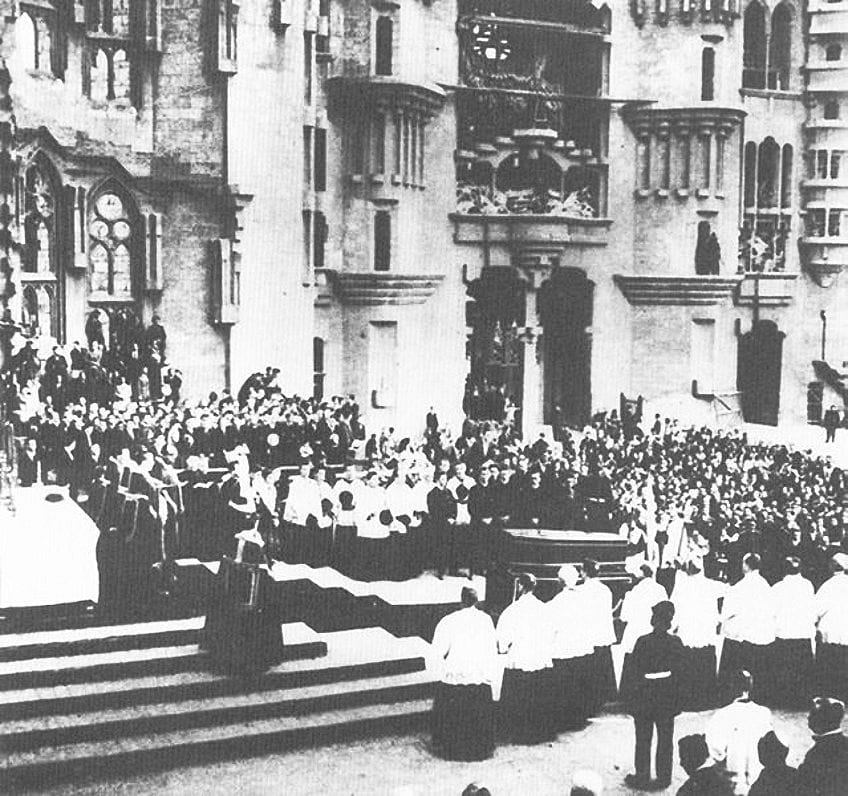

Gaudí, whose commitment to his Catholic religion had become practically his main passion outside of his architectural firm by 1914, discontinued construction on all other buildings except the Sagrada Familia, which consumed him until his demise in 1926.

On the 7th of June in 1926, he was traveling from work to the church of Sant Filip Neri for his prayer services when he was hit by a tram and fell unconscious.

Because of his drab attire and lack of identification documents, he was mistaken for a vagrant, and medical care was prolonged by nearly a day as a consequence. He was ultimately recognized by the Sagrada Familia’s chaplain, but his health had deteriorated and he died a few days afterward.

Gaudí was given a grandiose burial and placed in the crypt of the Sagrada Familia, despite the cathedral being far from finished at the time of his death.

The Art Style and Legacy of Antoni Gaudí

Throughout his almost 50-year autonomous practice, Gaudí devised and produced some of the most innovative architectural forms in history, all in his home Catalonia, which has since become associated with the region’s character.

Gaudí has attracted and influenced generations of architects and even engineers as the best-known – and most unique – representation of Catalan Modernisme (Art Nouveau). With some of the most original, eccentric, and iconic designs of all time, his work now has a global audience.

Gaudí was very original in his structural investigations, looking through a range of regional influences before settling on the hyperbolic, parabolic, and catenary masonry structures and slanted columns that he built in his studio using weighted models. These are frequently combined with natural and profoundly symbolic religious iconography, which adorns Antoni Gaudí’s buildings with brilliant, colorful coverings. Gaudí’s architecture is the most imaginative, audacious, and showy of Catalan Modernisme designers, although it is not unusual for the genre as a whole.

Gaudí’s art is very personal, thanks in part to his religious Catholicism, which grew more intense as his career proceeded. Because of this, his work has numerous references to spiritual themes, and he progressively maintained an austere living towards the point of death, even foregoing all other projects to focus on his ideas for the Sagrada Familia church.

On his projects, Gaudí frequently cooperated with several other Catalan designers, manufacturers, artists, and artisans, most notably Josep Maria Jujol, who was often credited for the fractured tilework that is characteristic in many of Antoni Gaudí’s buildings.

This explains why Gaudí’s architecture frequently incorporates a diverse range of materials employed in imaginative and smart ways.

Examples of Antoni Gaudí’s Spanish Architecture

Not that we have covered Antoni Gaudí’s biography, we can move on to exploring a few examples of his renowned architectural style. Gaudí’s architecture was considered to be stylistically unique. Here are some of the most well-known examples of Gaudí’s Spanish architecture.

Casa Vicens (1883)

| Year Completed | 1883 |

| Medium | Stone, Brick, Iron, Ceramic Tile |

| Location | Barcelona |

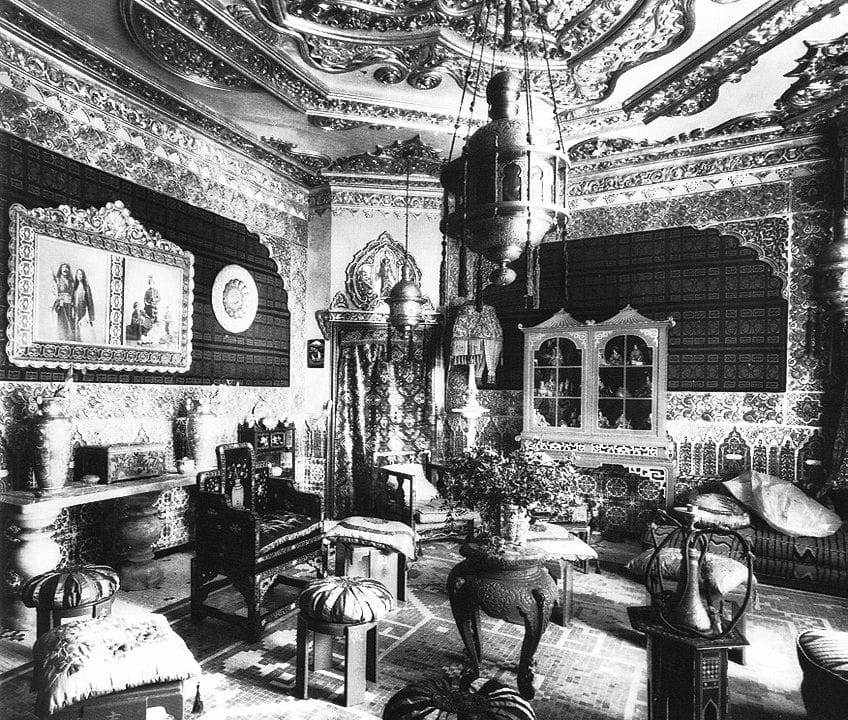

| Style | Neo-Moorish |

The Casa Vicens, which was first opened to the public in 2017, is widely regarded as Gaudí’s first noteworthy work. The project was a house for the tile and brick producer Manuel Vicens I Montaner, who had recently received the site from his mother-in-law when he engaged Gaudí in 1877, though work would not begin until 1882. As a result, Gaudí had a ready supply of the construction materials, and the framework itself showcases the functionality of Vicens’ factories, serving as a commercial for its owner’s ventures, the Barcelona construction sector, and the prodigious craftsmanship of the area’s artisans.

Gaudí’s design, in the neo-Moorish manner that echoes medieval Spanish Islamic architecture, is deliberately positioned to make use of these readily accessible building materials.

To highlight the varied structural capabilities of the material, the red brick tower with stone infill employs sawtooth patterns, stepped archways, complex bracketing under projecting terraces, pointed arches, and roof turrets. Similar tactics are employed to generate a kaleidoscope of color with the covering checkerboard-patterned and flowery tiles, which is a characteristic typical to Muslim architecture. The link with nature, which is distinctive of Art Nouveau and which this building contributed to the development of Barcelona, can be observed both inside and outside.

Not only is it shown on the tile, but the ironwork of the fencing (which used to enclose a larger set of grounds than that which remains now) has a dominant pattern of the Margallo palm, a plant endemic to Catalonia, and the iron grilles above the windows are reminiscent of twisted tendrils. These natural elements continue into the inside, where the domed ceilings of the dining room have been decorated to gaze up to the sky and are adorned with floral images.

Palau Güell (1888)

| Year Completed | 1888 |

| Medium | Stone |

| Location | Barcelona |

| Style | Modernism |

The textile mogul Eusebi Güell’s association with Gaudí began eight years before he contracted the designer to create his main mansion in Barcelona’s El Raval area. Gaudí did not let his patron down. The mansion is reached by a double-arched gateway covered with stunning looping vine-like ironwork that allows horse-drawn vehicles to enter through one archway and depart through the other.

Between the twin arches is a giant piece of wrought iron that resembles entangled seaweed; in the middle is a banner with the Catalan flag’s unique stripes, revealing Gaudí & Güell’s fervent regionalism.

The interior design is centered on an inventive square-plan core area that stretches four stories up into the heart of the structure and serves as a vast welcome hall for visitors, who must turn around to arrive from the summit of the stairs coming up from the garage underneath.

The more private quarters, as is customary in an urban European palazzo, are on the higher levels, with concealed windows overlooking the waiting area that allow inhabitants to see their guests before seeing them downstairs.

The reception hall is also enclosed with an inventive high paraboloid domed ceiling decorated navy blue to represent the night sky, which Gaudí perforated with tiny holes openings so that lamps could be hung above (on the inside of a tall spire that blocks the ceiling) and the glow filtered into the space below strongly resembles twinkling stars. The overall effect appeared to convert the inner reception hall into a starlit external courtyard.

Casa Batlló (1906)

| Year Completed | 1906 |

| Medium | Stone, Iron, Tile, Glass |

| Location | Barcelona |

| Style | Art Nouveau |

The Casa Batlló is unique among Antoni Gaudí’s buildings in that it is a remodel of a preexisting structure, which was constructed in 1877. Josep Batlló, the building’s proprietor since 1900, contracted Gaudí intending to demolish the structure and start again, but Gaudí persuaded him to just refurbish it.

Due to the cage-like framing over the second-floor openings, whose vertical parts imitate the forms of human bones with their delicate curves, the eventual redesign has been dubbed the “House of Bones.” The parallel is appropriate because the home seems to have no straight lines in its construction; the light fixture over the dining table is set into a blue ceiling with spiral shapes that resemble water around a drain.

The front surface is covered with delicate tiles blended with glass, creating a shimmering appearance among the different sculptural balconies that resemble face masks worn by Mardi Gras revelers. Day and night, the building attracts attention like a huge vertical sheet of elaborately organized jewels, injecting new life into an otherwise unexceptional structure.

The iconography at the top of the construction, nevertheless, is most significant, with a tower capped by a cross and perforated with the tiled monograms of the Holy Family in the Christian faith. The tower rises from a sloping roof of iridescent tiles. The shape of the turret is claimed to mimic the hilt of St. George’s sword, the patron saint of Catalonia, whose blade is penetrating the skin of the dragon that he slays.

In this sense, the structure demonstrates the very personal quality of the design, expressing both Gaudí’s regionalism and his Catholicism.

Colònia Güell (1918)

| Year Completed | 1918 |

| Medium | Brick |

| Location | Barcelona |

| Style | Catalan Modernism |

Gaudí’s second massive construction development for Eusebi Güell, the Colònia Güell, is notable for two primary reasons. In the first place, it illustrates how Gaudí and his benefactor comprehended the possibilities of modern architecture to form and change the lives of people of all social categories in both material and religious ways. In the second place, it was a method for Gaudí to keep improving the parabolic structural system that became practically a cornerstone of his subsequent works.

The Colònia Güell was a tool used by Güell to combat anarchism and socialism among workers in numerous metropolitan towns, notably Barcelona, around the end of the century. As a result, he chose a rural setting for his factory town and supplied his employees with the resources they needed for education, wellbeing, leadership, and religious well-being.

The latter was to be supplied by a large stone chapel with many parabolic spires, decorated with roof tiles, and crafted by Gaudí in 1898, although the foundations were not laid until 1908. Gaudí designed the workers’ dwellings in a simple, neo-Mudejar architectural form evocative of his early works, and several of the service buildings were built by his associates, including Francesc Berenguer.

The chapel is the most significant architectural component of the complex.

This was designed by Gaudí using a weighted version of interwoven threads suspended upside down from the roof in his workshop to figure out the features of the main sanctuary space’s parabolic form. This model is currently on exhibit in Barcelona’s Sagrada Familia Museum, and it certainly impacted Gaudí’s design for the vast metropolitan cathedral with its 18 spires.

Antoni Gaudí, a Spanish architect, is widely regarded as the most famous representative of Catalan Modernism. Gaudí’s architecture is well-known for its distinct and individualized style. Many of Antoni Gaudí’s structures may be located in Barcelona, including some of his most significant contributions to Spanish architecture, such as the Sagrada Familia Church. God, nature, and architecture were three of Gaudí’s primary life loves that inspired his art.

Take a look at our Gaudí architecture webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Were Gaudí’s Paintings Well-Known?

Antoni Gaudí was mostly known for his unique architecture. Yet, Gaudí’s paintings were also rather unique and interesting in their own right. An example of Gaudí’s paintings is Barcelona View at Sunrise.

What Is Antoni Gaudí Most Known For?

With some of the most original, eccentric, and iconic designs of all time, his work now has a global audience. Gaudí’s structural experiments were quite creative, exploring through a variety of regional inspirations before deciding on the hyperbolic, parabolic, and catenary brick structures and slanted columns that he produced in his studio using weighted models. These are frequently combined with natural and profoundly symbolic religious iconography, which adorns Antoni Gaudí’s structures with brilliant and colorful coverings.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Antoni Gaudí – An Exploration of the Life of This Spanish Architect.” Art in Context. March 10, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/antoni-gaudi/

van Huyssteen, J. (2022, 10 March). Antoni Gaudí – An Exploration of the Life of This Spanish Architect. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/antoni-gaudi/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Antoni Gaudí – An Exploration of the Life of This Spanish Architect.” Art in Context, March 10, 2022. https://artincontext.org/antoni-gaudi/.