Islamic Architecture – Building Styles Across the Muslim World

Islamic architecture refers to the architectural styles connected to Islam. Muslim architecture includes religious and secular types from Islam’s ancient past up to the present day. Islamic architecture characteristics include pointed arches, domes, and geometric designs. To find out more about Islamic buildings, such as which type of dome is most commonly used in Islamic architecture, read further as we explore this fascinating Middle Eastern architecture style.

Table of Contents

- 1 Exploring the History of Islamic Architecture

- 2 Islamic Architecture Characteristics

- 3 Famous Islamic Buildings

- 3.1 The Citadel of Aleppo (Aleppo, Syria) – c. 3rd Millennium BC

- 3.2 The Dome of the Rock (Jerusalem, Israel) – 691 CE

- 3.3 The Great Mosque of Samarra (Samarra, Iraq) – 851 CE

- 3.4 Great Mosque of Córdoba (Córdoba, Spain) – 988 CE

- 3.5 Jame’a Mosque of Isfahan (Isfahan, Iran) – 1088

- 3.6 The Alhambra (Granada, Spain) – 1238

- 3.7 Suleymaniye Mosque (Istanbul, Turkey) – 1558

- 3.8 The Taj Mahal (Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India) – 1653

- 4 Frequently Asked Questions

Exploring the History of Islamic Architecture

Traditionally, the Islamic world encompassed a vast geographical territory stretching from Europe and Western Africa to eastern Asia. Muslim architecture styles share common features across all of these locations, but over time, various areas established their own styles based on regional techniques and materials, local royal families and customers, and, in some cases, distinct religious allegiances.

Byzantine, Roman, Iranian, and Mesopotamian architecture, as well as the architecture found in all other lands seized by the Early Muslim conquests in the 7th and 8th centuries, inspired Early Middle Eastern architecture.

As Islam extended to Southeast Asia, it was also impacted by Indian and Chinese architecture. Subsequently, it took on distinctive features in the form of Islamic buildings and surface decoration with Islamic arabesques, calligraphy, and geometric elements.

Origins

The Islamic era started in early 7th-century Arabia with the founding of Islam under the direction of Muhammad. The very first mosque was erected in 622 CE in Medina by Muhammad shortly after his relocation from Mecca, and it corresponds to the current site of the Prophet’s Mosque. It is commonly referred to as his residence, but it may have been built from the start to function as a community center.

It was a modest courtyard construction made of unbaked brick with a rectangle, almost square floor plan of around 56 by 53 meters. On the courtyard’s northern side, in the direction of prayers, which was originally facing Jerusalem, stood a shaded portico sustained by palm trees.

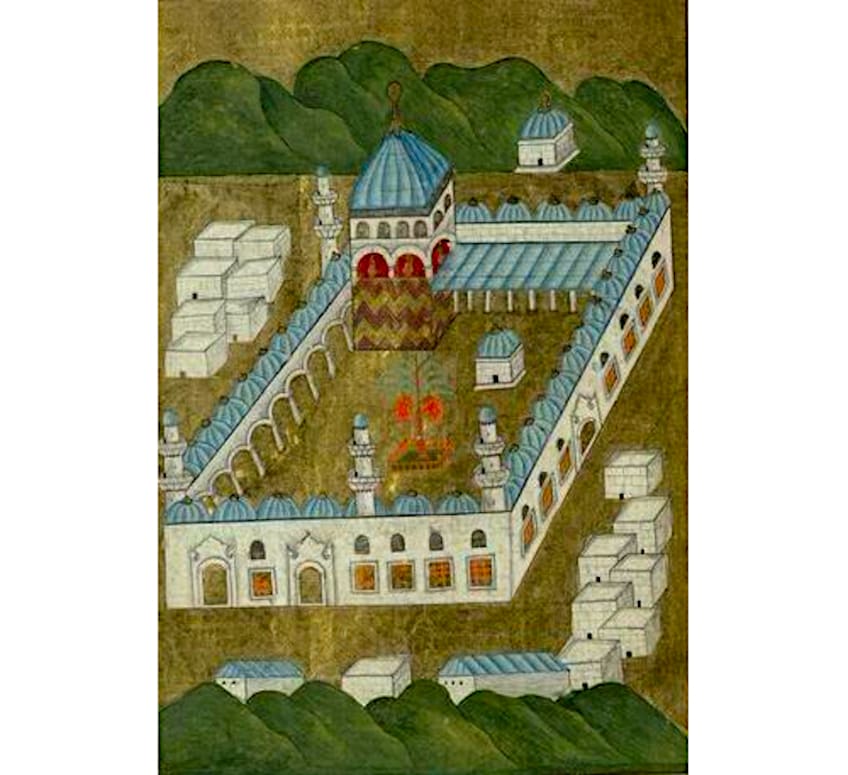

The Masjid al-Nabawi in Medina as seen 1750; The National Library of Israel Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

When the direction of prayer was shifted to face Mecca in 624 CE, a matching portico was built on the southern side of the building. Muhammad and his household resided in separate rooms adjoining the mosque, and when he died in 632 CE, he was interred in one of these chambers. The mosque was continuously enlarged over the rest of the 7th and 8th centuries to contain a massive flat-roofed prayer hall with a central courtyard.

It became one of the primary models for early mosques constructed in other regions. Historians largely agree that, aside from Muhammad’s mosque, Arabian Peninsula architecture appears to have played only a minor effect in the development of subsequent Muslim architecture.

The Byzantine and Sasanian Empires (c. 395 CE – 1453)

Before the beginning of the Arab-Muslim conquests in the 7th century, the Byzantine Empire and the Sasanian Empire were the two largest empires in the eastern Mediterranean region and the Middle East.

Both of these empires had their own distinct architectural styles

Two Arab tribal states occupied the borders between these great civilizations, in the steppe regions and deserts of Palestine, Syria, Mesopotamia, and northern Arabia: the Lakhmids, who were customers of the Sasanian people at al-Hira, and the Ghassanids, who were customers of the Byzantines and secured their eastern borders. In their respective domains, these two Arab kingdoms were prominent benefactors of Middle Eastern architecture. Due to the lack of recognizable artifacts today, we don’t know much about their design, although they copied and modified the designs of their Sasanian and Byzantine suzerains.

Some of their structures, including the Lakhmid palaces of al-Sadir and Khawarnaq in al-Hira, a Ghassanid church with beautiful mosaic ornamentation at Nitil, and a Ghassanid hall integrated into the Umayyad country home at ar-Rusafa, are documented through archeology or historical writings.

The Ghassanid and Lakhmid cultures and architecture most likely played a later role in conveying and refining the architectural traditions of the Sasanian and Byzantine worlds to succeeding Arab Islamic rulers who built their political headquarters in the same territories.

Once the early Arab-Muslim invasions stretched from the Arabian Peninsula to North Africa and the Middle East in the 7th century, new garrison settlements were constructed in conquered lands, such as Kufa in Iraq and Fustat in Egypt. These cities’ principal congregational mosques were designed in the hypostyle style.

In some places, particularly in Syria, new mosques were built by converting or occupying sections of old churches, like those in Hama and Damascus. These early mosques lacked a minaret, yet simple shelters on the rooftops may have been built to shield the muezzin while making the call to prayer.

The Umayyad Era (661 – 750 CE)

The features of Sasanian and Byzantine architecture were blended in the Umayyad Caliphate, but Umayyad architecture created unique combinations of these forms. Because governmental authority and patronage were based in Syria, a former Byzantine/Roman province, the reuse of motifs from traditional Byzantine and Roman artwork was still prevalent. During this time, some previously built Ghassanid constructions appear to have been repurposed and changed. Nevertheless, since Umayyad patrons attracted craftsmen from around the empire, architects were free – or even urged – to blend aspects from other creative traditions and violate customary rules and limitations.

Umayyad architecture is characterized in part by the breadth and variety of ornamentation, which includes wall paintings, mosaics, sculptures, and carved reliefs. While figural motifs were prominent in monuments such as Qusayr ‘Amra, non-figural embellishments and more abstract themes were popular, particularly in religious Islamic buildings.

The Umayyads were the first to include the mihrab in mosque architecture, which is a concave alcove facing the prayer wall of the mosque. The first mihrab is said to have appeared when al-Walid I renovated the mosque of Muhammad in Medina in 707 CE.

It appears to have reflected the position of the Prophet when conducting prayer. This quickly became a traditional element of all subsequent mosques. The Umayyads also established the practice of making the aisle in front of the prayer hall larger than the others, separating the prayer space along its central axis.

The Great Mosque of Damascus and the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem are two prominent early Islamic architectural masterpieces completed during the Umayyad period. Al-Walid I also constructed the Al-Aqsa Mosque on the Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem, replacing an earlier basic construction completed around 670 CE.

The Abbasid Era (750 CE – 1258)

The Abbasid Caliphate’s architecture was heavily inspired by Sasanian architecture, which included aspects dating back to ancient Mesopotamia. Other references have been identified, including old Soghdian architecture from Central Asia. This was largely due to the caliphate’s political hub migrating farther east to Baghdad, Iraq’s new capital.

Carved stucco, vaulting, and painted wall ornamentation were all carried over from the late Umayyad period into the Abbasid period.

The courtyard design with hypostyle halls was used by all Abbasid mosques. The first mosque was erected in Baghdad by Caliph al-Mansur. Al-Great Mutawakkil’s Mosque of Samarra, which measured 256 by 139 meters and was covered with glass mosaics and marble panels, had a flat roof made of wood held up by columns. The prayer hall of Samarra’s Abu Dulaf Mosque had arches on rectangular brick piers running perpendicular to the prayer wall. Both of these mosques in Samarra feature spiral minarets, the only ones in Iraq.

In present-day Afghanistan, sat a mosque at Balkh which was around 20 by 20 meters in size. While the origins of the minaret are unknown, the first real minarets are said to have developed around this time period. Several Abbasid mosques erected in the early 9th century included minaret towers at the northern extremities of the structure, opposing the central mihrab.

The Malwiya minaret, a tower with a “spiraling” design erected for the Great Mosque of Samarra, is one of the most notable of them.

Early Regional Styles

After the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyad Caliphate in 750 CE, a new offshoot of the Umayyad dynasty took control of Al-Andalus in 756 CE, establishing the Emirate of Cordoba and attaining the pinnacle of its dominance in the 10th century during the Caliphate of Cordoba. The Great Mosque of Córdoba, erected around 786 CE, is the Iberian Peninsula’s first important monument of Moorish architecture.

This Al-Andalus architectural style was generally shared with Western North Africa’s architecture, from which successive empires in the area would develop and add to the region’s cultural growth.

The Great Mosque of Cordoba was notable for its distinctive hypostyle hall, which had rows of double-tiered, two-colored arches that were replicated and kept in succeeding modifications of the edifice. The mosque was rebuilt several times, with al-Hakam II’s addition contributing significant artistic advances such as interconnecting arches and ribbed domes, which were eventually emulated and expanded upon in other monuments in the vicinity.

In the 10th century, the creation of Madinat al-Zahra, a new capital, and colossal palace city, established an extraordinary complex of royal design and patronage.

Smaller structures, like the early version of the Bab al-Mardum Mosque in Toledo and the Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fez, show the region’s use of the same artistic features. The Abbasid Caliphate was partially divided into regional governments in the 9th century, which were ostensibly subject to the caliphs in Baghdad. In modern-day Tunisia, the Aghlabids were major supporters of architecture, having rebuilt the Zaytuna Mosque of Tunis and the Great Mosque of Kairouan in much of its current forms, as well as constructing several other monuments in the region.

In Egypt, Ahmad ibn Tulun founded a short-lived dynasty known as the Tulunids and constructed himself a new city as well as the Ibn Tulun Mosque, which was constructed in 879 CE.

It was heavily inspired by Abbasid architecture and is one of the most remarkable and well-preserved instances of Abbasid Caliphate architecture from the 9th century. The Fatimid Caliphate rose to dominance in Ifriqiya in the 10th century, constructing a new defensive capital at Mahdia. In 970 CE, the Fatimids relocated their power center to Egypt and established a new capital in Cairo.

Fatimid architecture in Egypt adopted Tulunid methods and materials, but also created its own distinct architecture.

Cairo’s earliest congregational mosque was al-Azhar Mosque, which was constructed simultaneously with the city and became the religious hub for the Ismaili Shi’a branch of Islam.

Islamic Architecture Characteristics

Early Islamic architecture was shaped by existing styles such as Byzantine, Roman, and Persian architecture. As Muslim architecture spread around the world, particularly to Asia, Mughal and Chinese architecture affected it. Here are some of the most common characteristics of Islamic buildings.

Minarets

A minaret is a tower that normally stands alongside a mosque. Its formal purpose is to give a vantage position from which to issue the call to prayer. Every day, the call to prayer is broadcast five times. Most contemporary mosques transmit the prayer straight from the prayer hall using a microphone and speaker system which is fastened atop the minaret.

The origins of the minaret and its earliest purposes are unknown and have long been a source of academic debate. The call to prayer was frequently performed from lower tower constructions in the early mosques, which lacked these minarets.

Domes

Domes were first used in South Asia with the founding of the Delhi Sultanate in 1204 CE. Domes in South Asia are more globular than the Ottoman domes, and considerably more so than the Persian domes.

Ottoman architecture produced a special style of monumental, representational structure based on the model of pre-existing Byzantine domes: broad central domes with enormous diameters were placed on top of a center-plan building.

Considering their massive weight, the domes appear to be weightless. Mimar Sinan, an Ottoman architect, built some of the most ornate domed structures.

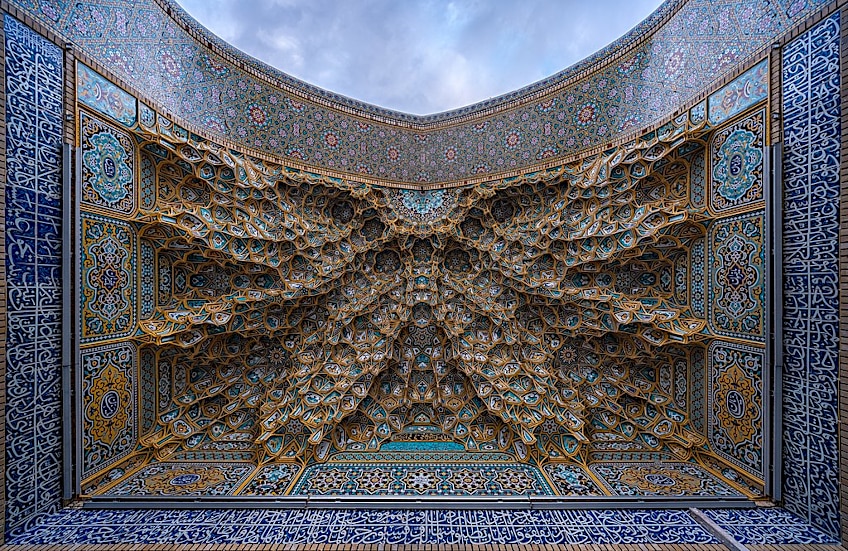

Muqarnas Vaulting

Muqarnas, also known as honeycomb vaults, are three-dimensional sculptural patterns formed by the geometric subdivision of a vaulting structure into smaller, stacked pointed-arch niches. They can be formed of various materials such as brick, stone, wood, or stucco. The oldest examples of this characteristic may be found in North Africa, Iraq, Central Asia, Iran, and Upper Egypt, dating from the 11th century.

Multiple academic theories concerning their origin and distribution have emerged as a result of their seemingly near-simultaneous growth in disparate areas of the Islamic world, with one current hypothesis arguing that they started in one place at least 100 years earlier and subsequently spread from there.

Vaulting

Vaulting in Islamic architecture follows two distinct architectural styles: While Umayyad architecture in the west continued Syrian traditions from the 6th and 7th centuries, Sasanian designs dominated eastern Islamic architecture.

Umayyad-era buildings exhibit a blend of old Persian and Roman architectural traditions in their vaulting systems.

Since the ancient and Nabatean periods, linteled ceilings and diaphragm arches composed of stone or wood beams, were common in the Levant. They were mostly used to cover buildings and cisterns. Later-period vaults were built with pre-formed gypsum lateral ribs that acted as a transitional formwork to direct and balance the vault.

Ornamental Details

Multicolored mosaic tiles with repetitive patterns and geometrical or botanical motifs and designs, such as the arabesque, are frequently used in Islamic decor.

Islamic decorative arts frequently incorporate Arabic scripts, such as Quranic texts.

Wood latticework is another eye-catching element that is utilized on windows for seclusion and climate management. It’s also employed as a simple aesthetic feature or choice for partitioning interior rooms in modern settings. Wall paintings, stucco sculptures, panels, and ornamental woodwork are further decorative components of the Islamic style.

Famous Islamic Buildings

Islamic architecture is one of the most famous building traditions in the world. This particular technique, known for its vibrant colors, complex patterns, and symmetrical forms, has been popular in the Muslim world since the 7th century. Here are some of the most famous Islamic buildings, including mosques, tombs, castles, and strongholds.

The Citadel of Aleppo (Aleppo, Syria) – c. 3rd Millennium BC

| Architect | Shaqwayq (c. 3rd millennium BCE) |

| Date of Completion | 3rd millennium BCE |

| Function | Citadel |

| Location | Aleppo, Syria |

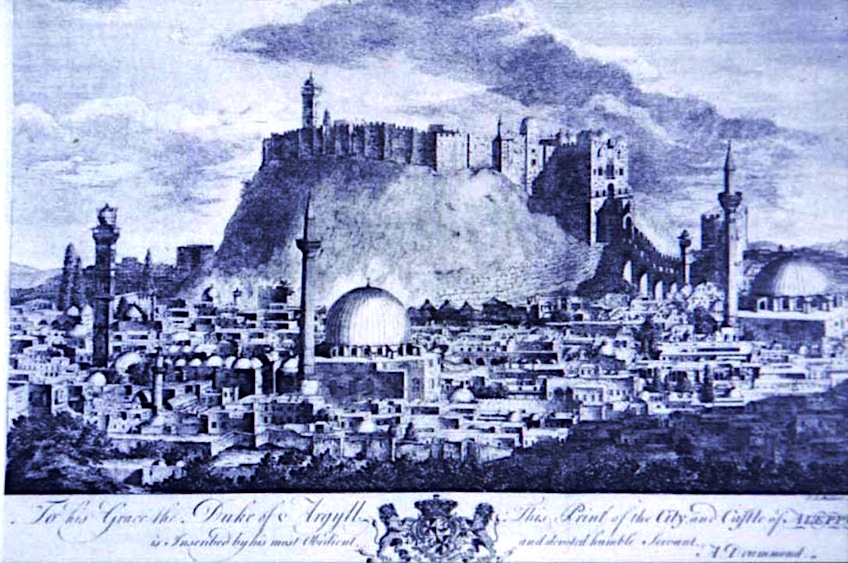

The medieval fortifications of Damascus, Cairo, and Irbil are among the most outstanding feats of Middle Eastern architecture. The citadel on top of a hill in the heart of Aleppo, Syria, is one of the greatest preserved representations of Islamic military architecture. Fortifications going back to Roman times and earlier have been discovered on the site, but the citadel was constructed in the 10th century and gained its modern shape after a significant extension and restoration during the Ayyubid Empire.

Inside the citadel’s walls are dwellings, supply rooms, wells, mosques, and defensive installations – everything required to withstand a protracted siege. The huge entry block, erected in 1213, is the most imposing feature of the complex.

A high stone bridge supported by seven arches goes across the moat to two enormous gates, the Gate of the Lions and the Gate of the Serpents. Invaders would have had to breach both gates and travel a meandering path as guards dumped boiling liquids onto them and arrows are thrown from multiple arrow slits wreaked from above.

The Dome of the Rock (Jerusalem, Israel) – 691 CE

| Architect | Raja ibn Haywa (660 – 730 CE) |

| Date of Completion | 691 CE |

| Function | Shrine |

| Location | Jerusalem, Israel |

The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem is the most ancient and most well-known Islamic structure. The architecture and decoration are steeped in the Byzantine architectural heritage but also reflect elements that would eventually come to be linked with a uniquely Islamic architectural style, despite being built 55 years after the Arab conquest of Jerusalem. The construction is made out of a gilded timber dome above an octagonal foundation. Two ambulatories wrap around an area of exposed rock within.

The location is significant to both Judaism and Islam; in Jewish history, it is claimed to be the location where Abraham prepared to slaughter his son in sacrifice, Isaac, while in Islamic belief, it is said to be the location of Muhammad’s ascension to paradise. Mosaics, marble, and metal plaques adorn the interior, which is lavishly embellished.

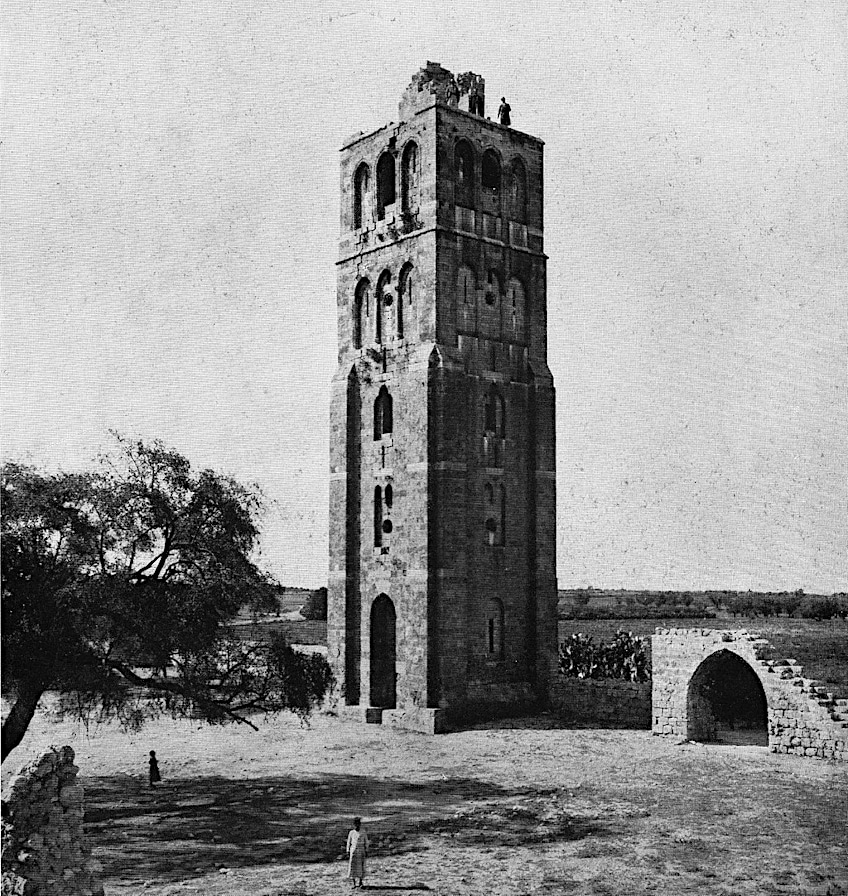

The Great Mosque of Samarra (Samarra, Iraq) – 851 CE

| Architect | Al-Mutawakkil (822 – 861 CE) |

| Date of Completion | 851 CE |

| Function | Mosque |

| Location | Samarra, Iraq |

The Great Mosque of Samarra is situated along the riverbanks of the Tigris River in Samarra, Iraq, some 120 kilometers north of Baghdad. It was constructed by the Abbasid caliph Al-Mutawakkil, who fled to Samarra to avoid confrontation with the local populace in Baghdad and stayed for the following 56 years, during which time he erected several palaces, including the biggest mosque in Islam.

It was the world’s biggest mosque for the next 400 years before being demolished by the army of Mongol emperor Hulagu Khan in 1278, during his conquest of Iraq.

The mosque has a rectangular plan surrounded by an outside baked brick wall 10 meters high and 2.60 meters deep and reinforced by 44 semicircular towers, four of which are corner towers. The mosque may be entered by one of 16 gates. Several little arched windows were said to be placed over each entryway. A frieze of recessed square niches with beveled frames follows the top course of the construction between each tower. The mosque contains 17 aisles and walls covered in dark blue glass mosaics. The courtyard was encircled on every side by an arcade, the largest portion of which faced the Holy city of Mecca.

Great Mosque of Córdoba (Córdoba, Spain) – 988 CE

| Architect | Hernán Ruiz the Younger (1514 – 1569) (later modifications) |

| Date of Completion | 988 CE |

| Function | Mosque |

| Location | Córdoba, Spain |

The mosque’s architecture is rich and distinguished by distinctive characteristics such as a hall of columns linked by patterned arches, a prominent orange garden, and a gold-inlaid mihrab.

The mosque was built using opulent Visigothic and Roman materials such as marble, jasper, and porphyry.

The complex has been expanded several times throughout the ages as it passed from Muslim to Christian control, adding various architectural features and patterns. Attempts have been undertaken in the last century or so to restore ancient Islamic architecture.

Abd al-Rahman I established the Arab dynasty that dominated the Iberian peninsula for nearly 300 years after their exile from Damascus. Aside from enhancing the land’s infrastructure and establishing his emirate, al-Rahman wished to construct a new mosque at Córdoba. Nevertheless, the structure changed hands several times, from Muslim to Christian control.

Several of the architectural aspects of the mosque had an impact on western architecture. It has become a notable example of a blend of Islamic and Christian design as it has changed hands throughout the years.

Jame’a Mosque of Isfahan (Isfahan, Iran) – 1088

| Architect | Malik-Shāh I (1055 – 1092) |

| Date of Completion | 1088 |

| Function | Mosque |

| Location | Isfahan, Iran |

The enormous Friday Mosque is located in the heart of Esfahan, a city rich in architectural gems. A mosque has been on the site ever since the 8th century, but the two domes that were erected during the Seljuk dynasty, which dominated regions of Iran in the 11th century, are the earliest sections of the existing edifice.

The mosque was erected in the early 12th century around a rectangular plaza flanked on every side by an iwan – a sort of hall that leads into a towering arch on one side. The four iwan-style, initially seen in Esfahan, eventually became the standard for Iranian mosques.

It is an Islamic architectural style that graphically embodies the political imperatives and aesthetic preferences of Persia’s major Islamic rulers. The mosque’s urban incorporation is another distinguishing feature. The mosque, located in the heart of the ancient city, shares walls with other structures that surround it.

The Alhambra (Granada, Spain) – 1238

| Architect | Muhammad I of Granada (1195 – 1273) |

| Date of Completion | 1238 |

| Function | Palace |

| Location | Granada, Spain |

The Alhambra is a palace erected in the 14th century by rulers of the Muslim Nasrid dynasty on a hillside which overlooks the Spanish city of Granada.

Although some elements of the palace have been destroyed, three components still remain, such as a fortification on the western end of the hill, a royal house to the east, and the Generalife, a group of gardens and pavilions.

The Alhambra’s chambers and courtyards are lavishly adorned with sculpted plaster, colorful tiles, carved wood, and calligraphy. The beautifully carved geometric stalactite decorations that cover the rooms around the Court of the Lions are among the most spectacular decorative elements.

Suleymaniye Mosque (Istanbul, Turkey) – 1558

| Architect | Mimar Sinan (d. 1588) |

| Date of Completion | 1558 |

| Function | Mosque |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

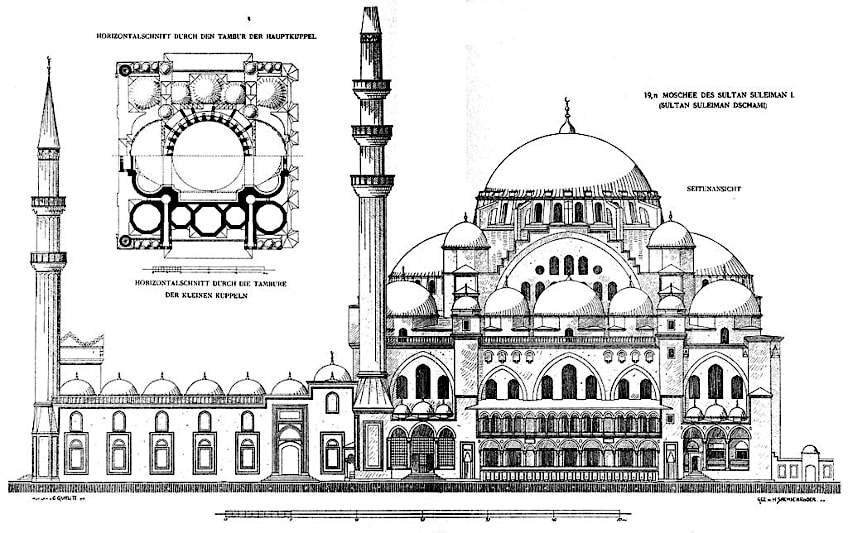

The towering minarets and dome of the Suleymaniye Mosque, which rises on a constructed plateau overlooking the Bosporus, are among the most conspicuous aspects of Istanbul’s skyline. It is the biggest and possibly the most spectacular of Istanbul’s imperial mosques built between 1550 and 1557 by Ottoman sultan Suleyman the Magnificent at the peak of the Ottoman Empire’s reign. The mosque’s interior is a single square-shaped space lit by over 100 huge windows, the majority of which are stained glass.

Elevation and plan of the Süleymaniye Mosque, Istanbul; Cornelius Gurlitt (1850-1938), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The decoration is basic and does not detract from the central dome’s enormous size, which spans 27.5 meters in circumference. A hospital, various religious schools, a series of shops, a tomb, and a bath are located surrounding the mosque.

The complex was created by the Ottoman architect Sinan, whose works were crucial in establishing a uniquely Ottoman style of architecture, and are regarded as one of his finest. Suleyman and Sinan are both interred in the compound.

The Taj Mahal (Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India) – 1653

| Architect | Ustad Ahmad Lahori (1580 -1649) |

| Date of Completion | 1653 |

| Function | Mausoleum |

| Location | Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India |

Mumtaz Mahal, the Mughal emperor’s favorite wife, died in 1631 while she was delivering their 14th child. Heartbroken, the emperor commissioned the Taj Mahal, a gigantic tomb complex on the Yamuna River’s southern bank that took more than two decades years to build. The Taj Mahal is now the most recognized piece of Islamic architecture in the world.

The monument is notable for its grandeur as well as its elegant form, which incorporates aspects of Islamic, Indian, and Persian design.

Visitors are startled by the center tomb’s white marble, which seems to shift color with the light. Close inspection reveals that the structure is beautifully adorned with semi-precious stones and Arabic calligraphy. Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal have fake tombs within; the genuine tombs are in a room under the ground level. Travelers stated in the 1660s that Shah Jahan wanted to create a similar tomb for himself made of black granite on the opposite side of the Yamuna; yet, current academics dismiss this as a fable with no basis in truth.

From the inception of Islam to the present day, Islamic architecture spans a vast spectrum of utilitarian and religious forms, affecting the construction and design of Islamic buildings, Muslim culture, and beyond. The main Islamic architectural types are tombs, mosques, palaces, schools, forts, and urban structures. Islamic architecture developed a rich vocabulary for all of these sorts of projects, which was also employed for less important structures like fountains, public baths, and home architecture.

Frequently Asked Questions

Which Type of Dome Is Most Commonly Used in Islamic Architecture?

An onion dome is a dome with the appearance of an onion. These domes are frequently greater in diameter than the tholobate on which they rest, and their height generally surpasses their breadth. These bulbous formations taper to a tip smoothly. Many massive Mughal domes were also double-shelled, following the Iranian style. The Tomb of Humayun’s architecture, notably its double-shelled dome, implies that its builders were acquainted with Timurid structures in Samarqand. The Taj Mahal’s central dome has a bulbous appearance and a double-shelled structure as well.

What Is Muslim Architecture?

Muslim architecture testifies to the Muslim community’s high degree of power and intellect during a period when Europe was in the medieval era. Whether it was the mosque, the palace, or the common home, Muslim masons, architects, and artists brilliantly communicated Islam’s profound dedication to the community. Early Muslim architects are responsible for most of the world’s architectural progress. It is now widely acknowledged that European Gothic architecture owed a significant debt to Islamic precedents, many of which were recognizable to Crusaders in Palestine, Egypt, and Syria.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Islamic Architecture – Building Styles Across the Muslim World.” Art in Context. February 10, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/islamic-architecture/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 10 February). Islamic Architecture – Building Styles Across the Muslim World. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/islamic-architecture/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Islamic Architecture – Building Styles Across the Muslim World.” Art in Context, February 10, 2023. https://artincontext.org/islamic-architecture/.