Japanese Architecture – Discover Traditional Architecture in Japan

Why is Japanese architecture important? Due to its remote location and isolation from the outside world for many years, traditional Japanese architecture has a unique style and identity. However, in more recent times, modern Japanese architecture has started to incorporate many influences from the Western world. There is much to explore about architecture in Japan – from Japanese traditional buildings to contemporary Japanese buildings.

Table of Contents

Exploring the Unique Architecture of Japan

Traditional Japanese architecture has an ancient history and a unique style that is easily identified even if you know very little about architecture in general. In ancient Japan, architecture was very similar to structures found in the rest of the world, consisting primarily of thatched roofs, wood, and mud floors.

It was only in the seventh century that Japanese traditional buildings began to develop their own particular aesthetic, having been strongly affected by other Asian cultures.

Although many of these traditions remain, modern Japanese architecture started to incorporate more Western, contemporary, and postmodernist elements into its architectural style as early as the 19th century. Currently, there is no set standard for what Japanese buildings should look like, as the country is seen as a pioneer in architectural technologies and design, leading the way for others to follow.

The History of Traditional Japanese Architecture

In the earlier periods of its history, the Korean Peninsula, as well as Chinese elements, have influenced architecture in Japan. Ever since the modern period, western society has also had an impact, while at the very same time, a distinct Japanese architectural aesthetic has emerged that incorporates Japan’s unique culture and environment. Traditional Ancient Japan architecture started to gain recognition in 20th-century Modernism.

This was because it was far ahead of the curve in the application of innovative architectural principles, as opposed to Western architecture, which mostly employed stones and bricks.

Ancient Japan Architecture

Japan absorbed architectural ideas from the Korean Peninsula and China throughout the Asuka and Nara eras. Temple building also started around 538 AD with the formal arrival of Buddhism in Japan. In 577 AD, shrine carpenters and manufacturers of Buddhist statues were recruited from Paekche, according to documents. The earliest Japanese Buddhist temples are Asuka-Dera Temple and Shitenno-Ji Temple.

The building methods and placement of Buddhist temples constructed during that period mirrored the architecture of temples in Paekche.

When Japanese delegations were dispatched to China during the Sui and Tong Dynasties, the impact of the architectural style of China increased. In the Heian period’s aristocratic age, architectural design started to incorporate distinctly Japanese traits, such as chambers with narrower pillars and low ceilings that created a relaxed environment.

During and shortly after the Heian era, a distinct Japanese architectural style known as Wayo Kenchiku emerged.

Medieval Architecture in Japan

The architectural styles of China were brought into Japan when trade with the nation expanded during the Kamakura era. The first design introduced to Japan was used in the reconstruction of the Todai-ji Temple. The Temple and the Buddha figure, both erected in the Tenpyo period, were ruined by fires that occurred during the Jisho-Juei War near the close of the Heian era. In 1811, Chogen Shunjobo dedicated the newly constructed Great Buddha statue, after facing many building challenges.

In 1195, the Great Buddha Hall was constructed, and in 1203, a spectacular memorial service was organized.

The building design of Chogen’s Great Buddha Hall and other such restorations was highly distinctive, bearing similarities to the building manner of Fujian Province and the outlying areas of China constructed during the Sung dynasty. Even though the architectural style, which combined practical structures and dramatic design, was appropriate for the Great Buddha Hall, it was inconsistent with the Japanese desire for a tranquil environment, and therefore Daibutsu-Yo fell out of favor after Chogen’s passing.

The craftspeople who worked on the renovation of the Great Buddha Hall returned home after the construction, and a distinct Japanese architectural form called Setchu-yo emerged, influenced by Daibutsu-yo.

Early Modern Japanese Architecture

The Momoyama era in the Japanese historical context represents a period between the fall of the Muromachi shogunate in 1573 and the defeat of the Toyotomi dynasty in 1615. Throughout this time, castle architecture boomed; castle towers were erected as a sign of authority, and magnificent murals were painted on walls to symbolize the nation’s union. Sen no Rikyu perfected tea rituals, which began in the Muromachi era, and a distinctive type of architecture specifically for the tea room was established.

During the Edo era, when public cultural life blossomed, there was a definite inclination towards secularism in the sphere of architecture.

The Sukiya-Zukuri design is representative of this movement, in which Chashitsu characteristics were integrated into residential constructions as well as urban recreational venues such as brothels and theaters. Residential dwellings developed progressively as well, absorbing elements of the Shoin-Zukuri design in part.

Huge main halls, such as those found at Senso-Ji Temple and Zenko-Ji Temple, were erected in temple architecture to facilitate a growing congregation.

Modern Japanese Architecture

In the final years of the Tokugawa shogunate, several international communities erected trading establishments, homes, and churches for people from other nations. The Glover Mansion was erected by Japanese workers under Glover’s supervision, although other features were completed by visiting European architects.

Japanese architects started to create Western-style homes and structures after being influenced by these new constructions in foreign communities.

The Japanese state was eager to absorb Western architectural innovations in the early Meiji era to create the communities needed to develop the region. Skilled individuals were invited to work in Japan, such as Thomas Walters and Josiah Conder, who dedicated their attention to educating Japanese designers at the Imperial College of Engineering. Kingo Tatsuno was among the university’s earliest graduates.

Due to their plans to create several government buildings, the Japanese recognized the need for architects, and so solicited aid from the German authorities, a developed European country that the Japanese greatly respected.

Wilhelm Beckmann and Hermann Ende’s architectural company was chosen to collaborate with the construction, and the two men were dispatched to Japan.

The Japanese administration sent a training group to Germany comprised of 20 up-and-coming Japanese designers such as Yuzuru Watanabe, Yorinaka Tsumaki, Kozo Kawai, and senior workers specializing in carpentry, stonemasonry, brick-laying, roofing, painting, and plastering. This was in response to the Germans’ suggestion that some representatives be taken to Germany to learn and obtain the required methods needed for constructing a modern nation.

The three-year trip provided a wealth of information and several of the participants went on to play key roles in architectural communities, and some became the first alumni of the Tokyo Institute of Technology. The architecture was traditionally regarded as a modernizing discipline to be acquired from the West, and the notion of design as an art form did not evolve in Japan. Several earthquakes caused significant damage to brick structures, prompting the construction of quake-resistant techniques that are unique to Japan.

As a consequence, there has been a propensity to consider architecture exclusively as a purely technical concept, and this viewpoint is still very much prevalent today.

Contemporary Japanese Buildings

After sustaining a heavy setback during WWII, the Japanese architectural movement had the opportunity for expansion during postwar reconstruction efforts and a time of great growth in the economy. The use of ferroconcrete was widespread, and public Japanese buildings throughout the country were constructed in modern-style architecture.

For the Japanese, frequent earthquakes were a threat, but as earthquake-resistant techniques developed, the elevation restrictions of 31 m were relaxed, and more high-rise structures were developed.

Japan started to produce several globally recognized architects, like Fumihiko Maki, Kenzo Tange, and Tadao Ando, and the quality of modern Japanese architecture increased. However, except for a few architects during the Taisho and early Showa eras, the notion of beautiful landscapes in cities was largely lost throughout the war and postwar reconstruction years.

Many classic cityscapes and magnificent examples of traditional Japanese architecture were destroyed throughout the war and also during the economic expansion, and there was an increase in the number of low-cost structures that prioritized economic rationale above everything else. Citizens started expressing fears that Japanese cities had become unsightly.

This prompted the creation of conservation zones for clusters of historic structures and the formation of the Landscape Law, which emphasized the aesthetics of towns and surrounding terrain.

The Various Styles of Architecture in Japan

Shinden-Zukuri is a Heian-era architectural style employed in aristocratic residences. In the Kamakura era, the Buke-Zukuri style was used for the samurais’ homes. The label Shuden-Zukuri is used to describe the design aesthetic of samurai homes during the Muromachi era. Now let us take a deeper look at these and other styles of architecture in Japan.

Shinden-Zukuri

A Shinden is a dwelling built on stilts with roofs covered with Japanese cypress bark. It features an open construction that is only separated from the exterior by hinged plank doors. In the front, a garden with a pond was traditionally created. Based on town boundary plans of the then-capital Kyoto in the 11th century, the traditional design was generally for the high-ranking aristocracy.

Typically, the views from a Shinden-style dwelling included hills and water features, as well as miniatures of attractive locations from all across Japan.

Based on its size, the pond comprises multiple islands connected by a carved bridge. Although there are no Heian-era remnants of this sort of architecture, we can envision what it was like by reading records on old scrolls and journals of aristocratic ministers and their attendants. These landscapes, designed to be filled with natural beauty, were not just there to be appreciated, but also to be used as a venue for special ceremonial occasions.

Many kinds of notable yearly celebrations were held at nobles’ estates at that time.

Buke-Zukuri

The basic architectural style of samurai dwellings in this age was derived from Shinden architecture, but it appears that because the samurai’s way of life differed greatly from that of nobility, the style of the dwellings was altered appropriately. The Kamakura shogun’s huge villa was where the Gokenin congregated to perform rituals or feasts, and where it is also said that the shogun occasionally sat facing the Gokenin as part of a samurai society ritual.

Even though the specifics of samurai dwellings are unknown to this day, a conventional household is comprised of one structure with numerous rooms, such as a communal room, a guest room, an office, and a living room.

They were built with sturdy walls and moats around the structures, and the garden area was also smaller than in the Shinden architecture. Many scrolls were created around the end of the Kamakura era, depicting the homes of local Samurai. In these scrolls, we earn that the Samurai traveled to the Japanese government-assigned region and resided there to govern the surrounding territory, according to their specific tasks. They resided in rural regions, managed farms, and presided over farmers.

Shugden-Zukuri

The Shugden was a building where all everyday tasks could be carried out, complete with a chamber for Buddhist rites and a bedroom. Shugden-Zukuri architecture is recognized as a separate architectural style. There are no surviving examples of the Shugden-Zukuri style, and its qualities may only be deduced from available associated documents.

While constructed more recently, the Onjo-ji Temple’s drawing room is thought to retain certain characteristics of “Shugden-Zukuri” architecture.

Shoin-Zukuri

Shoin-Zukuri is a Japanese domestic architectural form that emerged during the mid-Muromachi Period. Shoin-Zukuri has had a significant impact on Japanese domestic architecture since then. A Shoin was initially used by Zen monks to study literature, with a raised floorboard stretching out into the space as a table. A shallow ornamental nook was built to contain calligraphy, artwork, and other decorations.

“Shoin-Zukuri” architecture was developed as a means for indicating social ranks and orders, reaching its zenith in the design of castles during the Azuchi-Momoyama Era.

Sukiya-Zukuri

Sukiya-Zukuri architecture is defined by the absolute lack of prestige and elegance that Shoin architecture emphasized. Its design is basic and refined, expressing a tea master’s ethos of avoiding external ornamentation and emphasizing inward self-improvement to engage visitors. The Sukiya-Zukuri style moved from teahouses to residences during the Edo Period.

Many modern homes and upscale Japanese restaurants are inspired by “Sukiya-Zukuri” architecture.

Gassho-Zukuri

Gassho-Zukuri is a style defined by its distinctive steep roof. The Gassho-Zukuri in Gokayama has become world-renowned, yet this form was previously frequently utilized in Japanese residential dwellings. The Gassho-Zukuri style is useful as a steep roof is required to keep rain from leaking into the home with a thatched roof.

Furthermore, it is well-suited for holding the load of snow that collects in locations with significant snowfall.

When silk production flourished in the middle of the Edo era, farmers began to build shelves for breeding silkworms in the space under their roof. Roofs that are not too high are challenging to construct in the Gassho-Zukuri style. However, it is believed that the ceiling was raised and made steeper to increase the area under the roof to make room for shelves to house the silkworm boxes.

Characteristics of Japanese Architecture

Because Japanese architecture is centered on religion, the majority of the most notable Japanese structures were temples. These Japanese buildings, oriented toward meditation and devotion, had the most complex and detailed design. Because wood has historically been the most common material used in the architecture of Japan, many constructions are made of it.

Wood has been used since the seventh century; as it was more affordable than building with stone. It was frequently left untreated to show off the inherent beauty of the texture.

Cedar was favored because of its exquisite wood grain, although pine was frequently utilized for construction. Cypress was popular roofing material. Shoji is adjustable panels that serve to link the area to the outside and are extensively utilized in Japanese design. Since glass isn’t widely used in the household, they are usually made of paper to enable light to pass through. Typical Japanese buildings will feature a wooden porch that wraps around the exterior of the residence, providing another link between the dwelling and the natural environment.

Most Japanese buildings feature a lower level where you can take your shoes off before entering. In Western architecture, this is similar to a traditional hallway where visitors are received as they enter. Tatami flooring is another important feature of typical Japanese residences.

These rice straw rugs are the focal point of many Japanese traditions, and they are gentle on the feet but also very durable.

Cement and stone became more common in residential constructions during the late 19th century, yet wood was still a popular architectural element because it helped to balance the structure and provided a Zen-like link to the environment.

Important Japanese Architects

Architecture in Japan has a long history that is intertwined with nature and spirituality. While many aspects of Japanese architecture are immediately identifiable, it is always developing and evolving, just the same as with Western architecture. Let us take a look at a few Japanese architects paving the way for modern Japanese architecture.

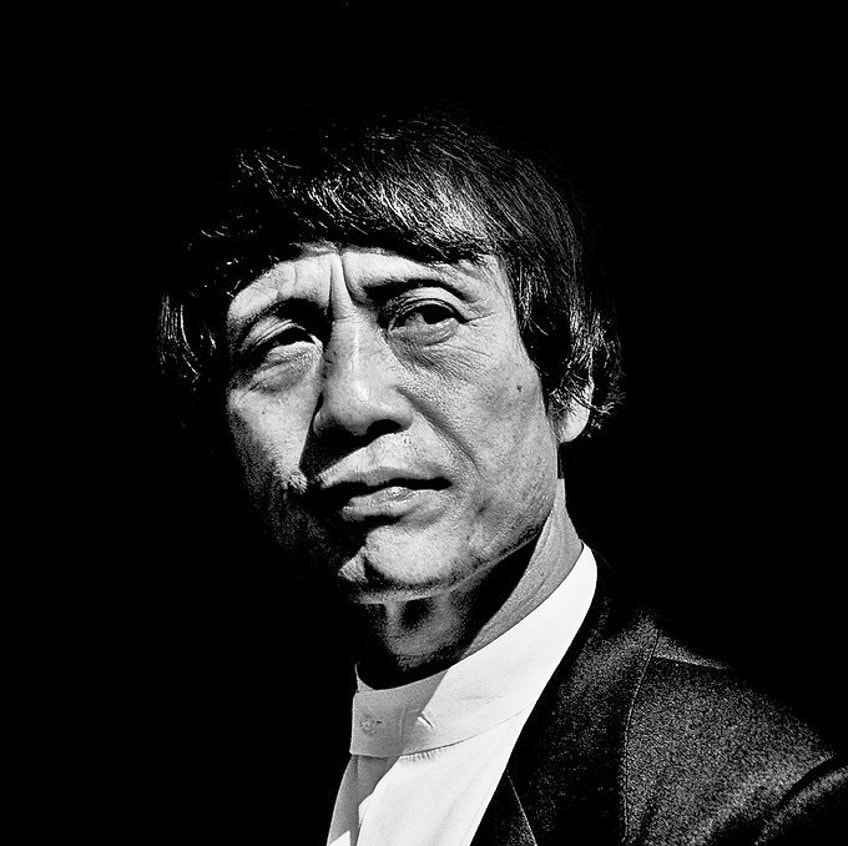

Arata Isozaki (1931 – Present)

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Date of Birth | 23 July 1931 |

| Date of Death | N/A |

| Place of Birth | Oita, Japan |

When the nuclear bombs were dropped on Japan, Arata Isozaki was only 14 years old. He stated, “My town was destroyed when I was just old enough to start comprehending the worId around me. I grew up near where the atomic bomb was dropped across the bay. It was destroyed, with no architecture, houses, or even a town. I was surrounded only by shelters. As a result, my first encounter with architecture was the absence of it, and I started to think about how people can reconstruct their houses and communities.”

He founded his architecture practice in 1963, during the Allied occupation when Japan had recovered its independence and was attempting physical reconstruction amidst cultural and economic uncertainties following WWII’s devastation.

He couldn’t limit himself to one style to discover the best solution to these difficulties. Change remained continuous, and ironically, this became his signature style. Almost all of the major Japanese designers of the 20th – century strove to combine indigenous customs with Western styles, materials, and technology.

Isozaki’s “signature” is a combination of modes formed in reaction to these inspirations. In his early days as an architect, Isozaki was vaguely affiliated with Metabolism, a Japanese movement formed around 1960. Yet, he downplayed his ties to this movement, viewing the Metabolist aesthetic as too industrial in tone.

In comparison, his work in the 1960s included dynamic shapes made available by the use of concrete and steel but not confined artistically by those same materials.

His concepts for the Fukuoka Mutual bank are typical of Isozaki’s early work. In the 1970s, his architecture grew more historically oriented, implying a relationship with the United States and Europe’s developing post-modern movement. Subsequently, his Western influences were strongly mannerist, with Michelangelo and Giulio Romano serving as references instead of the classicists.

This newfound concern with intricacy and ambiguity coincides with Isozaki’s desire to develop outside of Japan. Isozaki was one of just a few architects from Japan to have such an impression on the West. The assignments he secured in the United States and Europe demonstrate Isozaki’s prominence and reputation as an architect.

Tadao Ando (1941 – Present)

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Date of Birth | 13 September 1941 |

| Date of Death | N/A |

| Place of Birth | Osaka, Japan |

Tadao Ando was born and educated in Japan, where his architectural design was heavily inspired by faith and tradition. Tadao Ando’s style is believed to accentuate “nothingness” to express the grandeur of simplicity. He prefers to produce an intricate spatial flow while preserving the impression of minimalism. Ando is a self-taught designer who holds the Japanese language and culture in mind when traveling across Europe for study. He says that architecture has the power to influence culture, and that “changing the home means changing the community and reforming civilization.”

Ando’s minimalism stresses the notion of experience and tactile sensations, which is heavily motivated by Japanese culture.

Zen is a religious phrase that centers on the principle of minimalism and inner feelings rather than external appearances. These Zen influences are evident in Ando’s architecture and have become a distinctive feature of his work. To apply the principle of simplicity, Ando’s building is largely made of concrete, which provides a sensation of purity and weightlessness even though concrete is a substantially heavy material.

Because of the minimalism of the outside, the structure and arrangement of the area are quite capable of representing the Zen sensation. In addition to designing Japanese religious buildings, he has also designed several Christian churches. Even though Japanese and Christian temples have unique traits, Ando approaches them similarly. He argues that there should be no distinction between religious design and domestic design.

In addition to discussing the essence of architecture, Ando emphasizes the connection between architecture and the natural world.

Through architecture, he wants people to be able to comfortably enjoy the essence and serenity of nature. He believes that architecture is essential for making visible the essence of the environment. This not only symbolizes his perspective of architecture’s significance in civilization, but it also explains why he devotes so much time to researching architecture through his own physical experience.

Itsuko Hasegawa (1941 – Present)

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Date of Birth | 1 December 1941 |

| Date of Death | N/A |

| Place of Birth | Shizuoka, Japan |

Hasegawa is regarded as one of Japan’s most influential architects. In 2018, she was named the inaugural recipient of the Royal Academy of Arts Architecture Prize, with the judges stating that her “designs emit an enthusiasm that may be perceived as utopianism.”

Hasegawa began her work as a designer with the Metabolist group before collaborating with Kazuo Shinohara.

She established her own office in Tokyo in 1979 and was the very first female architect in Japan to design a public structure, the Shonandai Cultural Center, which was intended to symbolize a condensed representation of the cosmos. Three elegant, modern domes make up the Yamanashi Museum of Fruit.

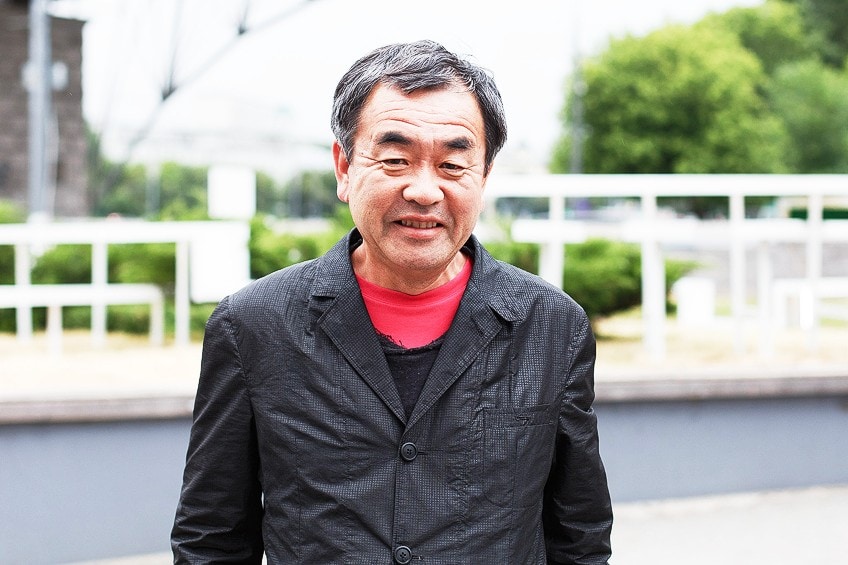

Kengo Kuma (1954 – Present)

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Date of Birth | 8 August 1954 |

| Date of Death | N/A |

| Place of Birth | Yokohama, Japan |

Despite adhering to Japanese principles in terms of structural purity, implicit tectonics, and the emphasis on lighting and clarity, Kuma does not limit himself to the basic and cosmetic use of ‘light’ materials. Rather, he goes far further, stretching to compositional processes to broaden the potential of materiality.

He makes use of technological advances to push unanticipated materials, such as stone, to provide the same impression of delicacy and gentleness as wood or even glass.

Kuma tries to achieve a feeling of spatial immateriality using the ‘particulate’ quality of light and by developing a link between a place and the natural world surrounding it. Kuma tried to describe his technique, stating that his goal is to repair the location. The most significant feature is that the location is the outcome of the environment and time. He considers his architecture to be a natural frame and that we may feel nature more fully and personally with it. Transparency is a feature of Japanese architecture, and he attempts to achieve a new level of transparency by utilizing light and natural elements.

The connecting spaces; the parts between the interior and the exterior, as well as from one room to the next, are the focus of many of Kuma’s designs. The selection of materials is motivated not so much by a desire to drive the creation of the shapes as it is by a desire to juxtapose comparable materials while demonstrating the technological improvements that have enabled new applications.

When it comes to stonework, his work stands apart from the pre-existing structures of substantial, massive, typical masonry construction.

Rather, his work catches the eye by narrowing down and removing the walls in an attempt to depict a certain “lightness” and immateriality, implying an impression of delicacy not usually seen in stone architecture.

That completes our look at Japanese traditional buildings through the ages. In ancient Japan, architecture in the region was influenced by the styles that originated in other Asian regions like China and Korea. Today, Modern Japanese architecture not only meets up to Western standards and designs but also easily surpasses them.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Is Japanese Architecture Important?

When Japan started its Westernization stage to compete with other industrialized nations, it was compelled to modify the way its architecture was designed. Although it had previously been easy to import concepts from other nations, Japan’s rising degree of expertise ensured that its own architects started to establish their own distinct styles. Uniquely Japanese skills were imparted, and architects who studied abroad brought the International Modernism approach to Japan with them.

Where Does Japanese Architecture Go Next?

Japan has gone through multiple eras of economic boom and fall, and technological improvements are expected to modify the definition of Japanese architecture even further. As a global leader in cutting-edge technologies, it is natural for Japanese architecture to welcome new methods and styles as they emerge alongside the technology that enables them. With no definite or distinct style, Japan still produces some of the most inspirational and imaginative architectural designs in the world.

What Are the Characteristics of Japanese Traditional Buildings?

Castles, shrines, and temples are examples of Japanese structures. Because Japanese architecture is oriented on religion, temples were the bulk of the most noteworthy Japanese constructions. Wood has been utilized since the seventh century since it is less expensive than stone. A typical Japanese house will include a wooden porch that extends around the outside of the house, creating a link between the home and the natural surroundings. Buddhist temples are still an important aspect of Japanese architecture today, and modern architects have even rebuilt a Buddhist shrine dating back to the Edo era. The architects modernized the shrine by adding a triangular entrance hall and exposed concrete sidewalls to the priest’s chambers.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Japanese Architecture – Discover Traditional Architecture in Japan.” Art in Context. August 31, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/japanese-architecture/

van Huyssteen, J. (2022, 31 August). Japanese Architecture – Discover Traditional Architecture in Japan. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/japanese-architecture/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Japanese Architecture – Discover Traditional Architecture in Japan.” Art in Context, August 31, 2022. https://artincontext.org/japanese-architecture/.