Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany – A Fairytale Castle Come True

Where is the Neuschwanstein Castle located and why was it built? Castle Neuschwanstein was built on a hill overlooking Hohenschwangau, a village in southwestern Bavaria in Germany, and was constructed to serve as a retreat for Bavaria’s monarch, King Ludwig II. When was the Neuschwanstein Castle built and how was it paid for? King Ludwig began construction on the famous German castle in 1869 using his personal fortune as well as borrowed funds, but the palace was never fully completed.

Table of Contents

Discovering the Facts About Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany

| Architect | Eduard Riedel (1813 – 1885) |

| Date Completed | Incomplete |

| Height (meters) | 65 |

| Function | Palace, castle, and museum |

| Location | Hohenschwangau, Bavaria, Germany |

Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany was used as the King’s private residence until his passing in 1886. Following his death, the famous German castle was opened to the general public. Today, around 1.3 million people visit the site annually to learn more about the building’s history and to view the Neuschwanstein Castle’s architecture as well as explore inside Neuschwanstein Castle.

We shall start our own exploration of this famous German castle by first looking at its history.

The History of Castle Neuschwanstein

Castle Neuschwanstein’s design embodies the architectural style that was fashionable at that time known as “Castle Romanticism”. It was also heavily inspired by (and was built in order of) Richard Wagner, the famous composer. A journey in 1867 also provided inspiration for the Neuschwanstein Castle’s architecture, as King Ludwig encountered several castles that were being reconstructed from old castle ruins into magnificent palaces, such as the Château de Pierrefonds, located northeast of Paris.

Design Inspiration

For the King, these palaces represented a romanticized version of the architectural styles of the Middle Ages – an aesthetic he wanted to incorporate into his own palace. Richard Wagner’s operas also left a lasting impression on him, and many of the artworks that would be featured inside Neuschwanstein Castle were based on the narratives of these plays.

When Ludwig I passed away in 1868, the King suddenly had the necessary funds to build his dream Middle-Ages-themed palace far away from Munich, the capital of the royal empire at that time. In his letters to Richard Wagner, the King stated his intention to build a magnificent palace on the ruins of a castle that once stood atop the hill overlooking the village of Hohenschwangau.

He added that he wanted to add certain elements that would remind Wagner of scenes from his works such as Lohengrin (1850) and Tannhäuser (1848).

King Ludwig was so insistent on achieving the idealized romantic castle that he envisioned in his imagination that he commissioned Christian Jank, a stage designer, to draft the castle’s design. The architect Eduard Riedel was commissioned to construct a palace based on the draft concept. Due to certain technical reasons, the existing ruins could not be incorporated into the design. Initially, the design was much simpler, drawing stylistically from existing structures such as Nuremberg Castle.

However, these designs were rejected by the King who demanded extensive redrafts, insisting that he approve of each step before they proceeded. He was involved to such a degree that many people now view the Neuschwanstein Castle’s architecture as the result of his input more than the architects who were employed to build it. At the time of its initial construction, Castle Neuschwanstein’s design was ridiculed by architecture critics who viewed the massive palace as “Kitsch”.

Nevertheless, today, it is considered to be one of the most significant examples of European historicism.

Neuschwanstein Castle is composed of a number of distinct buildings that were built along a 150-meter cliff crest. The elongated structure is adorned with a multitude of towers, ornate turrets, balconies, gables, pinnacles, and statues. The complex of separate buildings provides picturesque views of the castle from all angles, framed by the mountains of the Tegelberg with the Pöllat River to the south and the lakes of the Alpine foothills to the north.

It was created as the romantic view of a knight’s castle; but, unlike “actual” castles, whose construction is usually the consequence of decades of building activity, Castle Neuschwanstein was planned from the start as a deliberately asymmetric architecture, and developed in phases.

Standard castle features were incorporated, but true defenses, the most significant component of a medieval noble estate, were excluded.

Construction

The remnants of the medieval castles were entirely demolished in 1868, and the ruins of the ancient stronghold were blown up. The castle’s foundation stone was placed on the 5th of September, 1869; its cellar was completed in 1872, and construction up to the first story was finished in 1876, with the gatehouse built first. The gatehouse was finished and fully furnished by the end of 1882, enabling the king to take temporary quarters there and oversee the continuous construction work. In 1874, Riedel handed over control of the civil works to Georg von Dollmann. The Palas’ topping-out ceremony took place in 1880, and Ludwig moved into the new structure in 1884.

Once Dollmann fell out of favor with the Monarch, the work was handed over to Julius Hofmann the next year.

The castle started as a traditional brick structure and was eventually covered in various types of rock. The white limestone that they needed for the fronts was supplied by a local quarry. Schlaitdorf in Württemberg supplied the sandstone bricks for the gateways and bay windows. The arch ribs, windows, and capitals were all made of marble from Untersberg, near Salzburg. A steam crane that hoisted the cargo to the construction site assisted in the transportation of building supplies. Both boilers were examined on a regular basis by the newly formed Steam Boiler Inspection Association.

For over 20 years, the building site was the region’s primary employer. In 1880, the site was occupied by around 200 artisans, not including suppliers and other people who were indirectly participating in the building. When Ludwig insisted on very tight deadlines and urgent adjustments, up to 300 laborers per day were apparently active, often laboring at night assisted by the illumination of oil lamps. In 1870, an organization was formed to insure workers for a small monthly charge, which was supplemented by the King. Construction victims’ heirs received a little pension.

Ludwig moved into the (still incomplete) Palas in 1884, and for his mother Marie’s 60th birthday in 1885, he brought her to Neuschwanstein. The exterior construction of the Palas Hall was mainly built by 1886.

The initial wooden Marienbrücke over the Pöllat Gorge was replaced with a steel structure the following year by the King. Despite its enormity, Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany did not have the capacity for the royal court, instead housing just the King’s private quarters and servants’ quarters. The court buildings were built for ornamental rather than utilitarian purposes. The castle was basically built for King Ludwig II to function as a type of theatrical setting that was inhabitable.

Simplified Redesign

By the time King Ludwig died, the castle was far from completion. The outward constructions of the Palas and the Gatehouse were nearly done, however, the Rectangular Tower was still covered in scaffolding. Construction on the Bower had not commenced but was finished in a reduced version by 1892 but without the anticipated statues of the female saints.

The Knights’ House was also reduced in design. In the King’s plans, the Knights’ House gallery columns were represented as the trunks of trees and the capitals as the accompanying crowns. Just the foundations for the royal complex’s centerpiece remained: a 90-meter-high keep designed for the top courtyard, situated above a three-nave church.

This was not realized, and a connecting wing between the Bower and the gatehouse was also never built.

Upon the King’s death, proposals for a terraced castle garden with a fountain were also abandoned. The royal living quarters of the palace were largely finished in 1886, with the corridors and lobbies painted in a simpler manner by 1888. The King’s ambition for a Moorish Hall was not realized, nor was the so-called Knights’ Bath, which, modeled after the Wartburg’s Knights’ Bath, was supposed to pay respect to the knights’ worship as a medieval baptism bath. In reality, a comprehensive extension of Neuschwanstein had never been intended, and there was no utilization plan for several chambers at the time of the King’s death. The monarch never intended for the castle to be open to the public.

But, only two months after the death of the king, Prince-Regent Luitpold ordered that the castle be opened to paying guests. Until the outbreak of World War I, Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany was a consistent and valuable source of income for the House of Wittelsbach; in fact, King Ludwig’s palaces were most likely the Bavarian royal family’s single greatest source of revenue in the years preceding 1914. To guarantee a consistent flow of visitors, several rooms and court buildings were completed first. Guests were first able to walk freely throughout the castle, causing the furnishings to wear rapidly. The civil list was socialized when Bavaria became a republic in 1918.

The ensuing conflict with the House of Wittelsbach resulted in a division in 1923: Ludwig’s castles, including Castle Neuschwanstein, were given to the state and are currently administered by the Bavarian Palace Department.

Neuschwanstein Castle’s Architecture

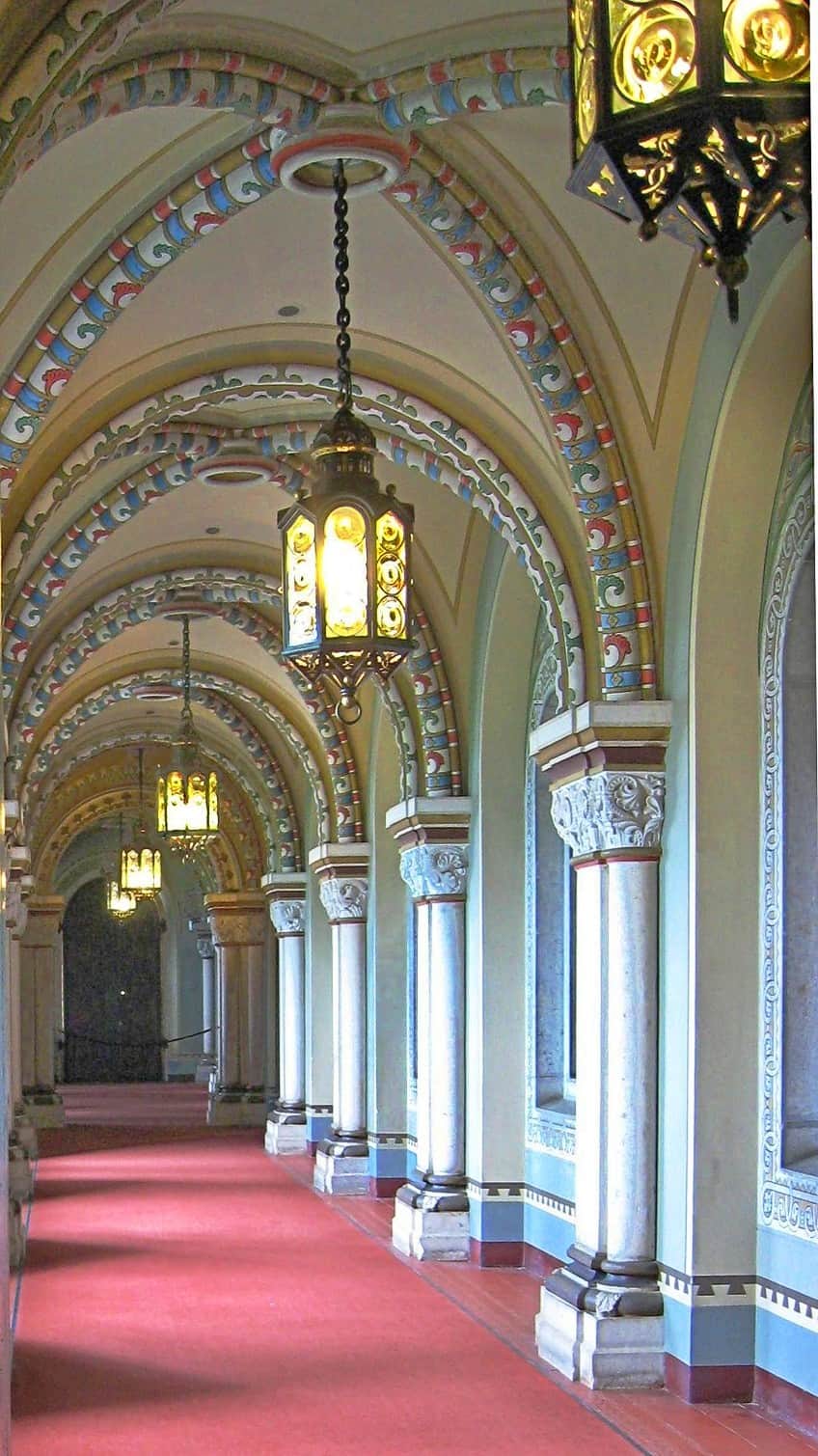

Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany is considered to be a typical example of 19th-century architecture. Elements of Romanesque, Gothic, and Byzantine architecture and art were merged in an eclectic style and complemented with 19th-century technical advances. The basic design was initially intended to be neo-Gothic, but the famous German castle was ultimately largely built in Romanesque style. Both externally and inside Neuschwanstein castle, the result is very stylistic.

The king’s touch is felt throughout, as he took a personal interest in both the palace’s design and decor.

The interior, particularly the throne chamber, is a continuation of the design of the royal Sicilian Norman-Swabian era churches and chapels in Palermo associated with the House of Hohenstaufen. The artwork makes reference to the German myths of Lohengrin, the Swan Knight, throughout Castle Neuschwanstein. Multiple rooms have borders representing Wagner’s many operas, including a theater that permanently displays the set of one of Wagner’s plays. Several of the interior rooms are still unfinished, with only 14 completed before the King’s passing.

The Exterior of Neuschwanstein Castle

The Castle Neuschwanstein complex is accessed via the symmetrical Gatehouse, which is enclosed by two stair towers. The eastward-facing gate building is the only edifice in the castle with a high-contrast color scheme; the court fronts are made of yellow limestone, while the external walls are made of red bricks. The upper level of the Gatehouse is topped with a crow-stepped gable and functioned as the King’s first residence at Castle Neuschwanstein, from where he often surveyed the hall’s construction before it was completed. The Gatehouse’s ground floor was designed to house the stables.

The path through the Gatehouse leads straight onto the courtyard, which is divided into two levels, with the lower one delineated to the east by the Gatehouse and the upper one marked to the north by the Rectangular Tower’s foundations.

The courtyard’s southern end is open, offering views of the surrounding mountain landscape. The courtyard is bordered at its western end by a bricked embankment, where a protrusion denotes the choir of the initially planned chapel. This church, which was never constructed, was supposed to form the foundation of a 90-meter keep, the planned architectural centerpiece. The chapel keep’s foundations are still visible in the pavement of the upper courtyard. The Rectangular Tower is the most prominent building on the upper court level.

It, like most of the courtyard structures, primarily serves a decorative function as part of the complex. The Knights’ House marks the upper courtyard’s northern end. The Knights’ House, according to castle romanticism in Europe, would have served as the residence of the soldiers; in Neuschwanstein, however, estate and service chambers were housed here. The Palas Hall marks the western side of the courtyard. It is the castle’s primary residential structure and includes the King’s stateroom as well as the servants’ quarters.

The Palas is adorned with several ornate chimneys and beautiful towers, and the court front is decorated with colorful frescoes.

The Interior of Neuschwanstein Castle

The castle would have included more than 200 rooms if it had been fully realized, including quarters for visitors and staff, however, in the end, only 15 halls and rooms were ever fully completed. The Palas’ lower stories house servants’ and administrative rooms, as well as quarters for today’s castle administration, and the top stories house the King’s staterooms.

The Throne Hall occupies nearly the entire top level of the west-facing posterior building.

The castle was also equipped with several of the newest technological advancements of the 19th century. It featured a battery-powered bell system for the castle staff, as well as telephone lines, among other features. A Rumford oven, which rotated the skewer with its warmth and so automatically changed the turning speed, was included in the kitchen.

The hot air was utilized to power a central heating system, while other historical innovations included flowing warm water and even toilets with automated flushing.

The Hall of the Singers

The Hall of the Singers, located on the fourth story above the King’s quarters in the Palas’ court-side wing, is the biggest room in the castle. This area was one of the King’s favorite projects for the castle and was created as a combination of two of the Wartburg Castle’s rooms: the Ballroom and the Hall of the Singers.

The rectangular chamber was designed with scenes from the mythical tales of Parzival and Lohengrin. The Hall of the Singers was never intended for the reclusive King’s court celebrations. Instead, it functioned as a walkable memorial to the lifestyle of knights and courtly love in the Middle Ages, similar to the Throne Hall. A concert marking the 50th anniversary of Richard Wagner’s death was held in this hall in 1933.

The Throne Hall

The Throne Hall is located in the Palas’ west wing. It is encircled on three sides by multicolored arcades, terminating in an apse that was supposed to house Ludwig’s throne but was never finished. The artworks on the throne dais depict the Twelve Apostles, Jesus, and six canonized monarchs. Wilhelm Hauschild produced the mural paintings in Throne Hall and the floor mosaic in the hall was only completed after the death of the king. The chandelier is designed to resemble a Byzantine crown.

The Throne Hall was designed to leave an impression of sacredness on those who entered.

The Royal Lodging Rooms

Apart from the big ceremonial chambers, King Ludwig II had other smaller rooms constructed for his personal use. The royal quarters are on the third story of the palace, in the Palace’s east wing. It is comprised of eight living rooms and various smaller rooms. Despite the extravagant decor, the living room, with its average room size and couches and suites, gives guests a relatively modern impression. King Ludwig II did not value the representational obligations of past eras when a monarch’s life was primarily public.

He also did not adhere to the aesthetic standards of the era, choosing to decorate the palace as he deemed suitable.

The interior design featured murals, tapestries, furniture, and other handicraft that usually corresponded to Ludwig’s favored themes: the grail myth, Wolfram von Eschenbach’s writings, and Richard Wagner’s interpretation of them. The eastward drawing room is decorated with elements from the mythology of Lohengrin. The furniture, which includes armchairs, a table, a sofa, and seats in a northward alcove, is pleasant and inviting. The passageway to the study is formed by a little artificial grotto next to the drawing room. The dining room, which is situated opposite the study, is decorated with images of courtly love.

The only remaining neo-Gothic rooms in the castle are the bedroom opposite the dining room and the later house chapel. A massive bed decorated with carvings occupies the King’s chamber. Around 14 carvers labored on the bed canopy with its multiple pinnacles and the oaken paneling for over four years. On the night of the 11th of June, 1886, the King was arrested in this chamber.

The servants’ quarters in the Palas’ basement are sparsely furnished with huge wood furnishings.

Apart from one table and one cupboard, there are two 1.80-meter-long beds. The chambers were divided from the passage that connects the outdoor steps to the main staircase by opaque glass windows, permitting the King to arrive and depart without being seen. The staff was not permitted to use the main stairs, but only the considerably smaller and steeper servants’ stairway.

That concludes our look at the facts about Neuschwanstein Castle. This renowned old castle is renowned as an architectural paradox. It was constructed at a period when castles were no longer needed as fortresses, and despite its idealized medieval style, King Ludwig II ordered it to include all of the latest technology amenities. Ludwig was a supporter of the composer, Richard Wagner, and the stories that inspired the composer are represented by wall paintings throughout the castle. Unfortunately, the king did not live to see the completion of the castle. In fact, it was never fully complete to the original plan and was largely simplified after his passing. After his passing, the castle was opened to the general public at a fee.

Frequently Asked Questions

When Was the Neuschwanstein Castle Built?

Construction started in 1869 after King Ludwig II had explored several castles in Europe that had been constructed from castle ruins. He hoped to do the same in his own country and wanted it to be a retreat based on the castles and landscape he had envisioned after listening to Richard Wagner’s music and plays.

Where Is the Neuschwanstein Castle Located?

It is located near the village of Hohenschwangau, built on the hills surrounding the village. The village is located in Bavaria and was built as a place where the king could live out his fantasies of residing in a Medieval palace. It would act as an escape from Munich, an inhabitable scene from a play or mythical story.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany – A Fairytale Castle Come True.” Art in Context. August 22, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/neuschwanstein-castle-in-germany/