Sainte Chapelle in Paris – Awe-Inspiring Architecture

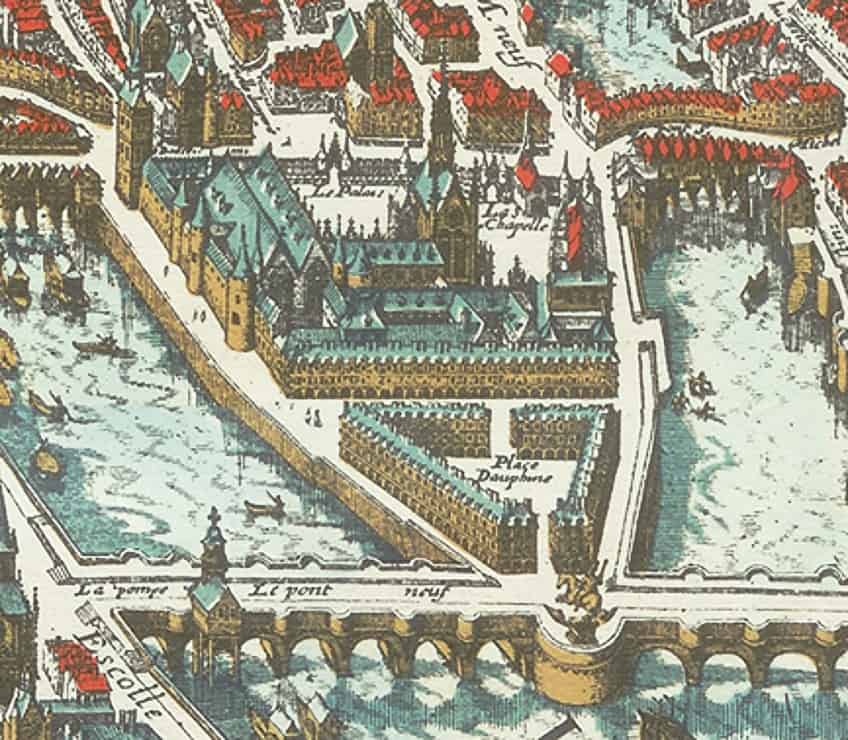

Why was Sainte Chapelle Cathedral built and where is the Sainte Chapelle located? The Sainte Chapelle in Paris is located within the Palais de la Cité, home to France’s Kings up until the 14th century. This display of devotion and authority under the French religious monarchy eventually became a renowned symbol of France’s craftsmanship and majesty throughout Europe. Today, we shall be looking at the history and architecture of the Sainte Chapelle in Paris, and answering questions such as, “why did Louis IX design the Royal Chapel of Sainte Chapelle with two entrances?”.

Table of Contents

Exploring the Sainte Chapelle in Paris

| Architect | Pierre de Montreuil (1200 – 1267) |

| Date Completed | 1248 |

| Height (meters) | 36 |

| Function | Cathedral and museum |

| Location | Palais de la Cité, Paris, France |

Sainte Chapelle Cathedral is one of the oldest extant Capetian royal palaces in the Île de la Cité, an old and beautiful island in the Seine River. Despite being damaged due to the French Revolution and reconstructed in the 19th century, it features one of the world’s finest stained glass collections from the 13th century. The cathedral, together with the adjoining Conciergerie, the other intact remnant of the old palace, is currently run by the French Centre of National Monuments and functions as a museum.

History of the Sainte Chapelle in Paris

Sainte Chapelle Cathedral was modeled on older Carolingian royal chapels, most particularly Charlemagne’s Palatine Chapel at Aachen. It was constructed in approximately 800 CE and used as the Emperor’s oratory. Louis IX had previously erected one chapel, connected to the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, in 1238. This older building had only one story; its design was used for Sainte Chapelle in Paris, but on a far bigger scale. The two equal-sized floors of the new chapel served completely diverse roles.

The highest tier, which housed the sacred artifacts, was just for the royal family and their entourage.

The lower floor was utilized by the palace’s staff, consorts, and military. In addition to functioning as a house of worship, the Sainte Chapelle Cathedral played a critical role in King Louis’ and his successors’ cultural and political aspirations. Louis’ support for the arts and architecture contributed to positioning him as the pivotal emperor of western Christendom and positioning Sainte Chapelle in Paris as one of the region’s most esteemed palace chapels. At the time, the Holy Roman Empire was in an unsettled state of disorder with only the Count of Flanders sitting on the imperial throne in Constantinople.

Just as the ruler could enter the Hagia Sophia secretly from his residence in Constantinople, Louis, too, could now enter the Sainte-Chapelle directly from his residence. More significantly, the two-floor palace chapel bore striking resemblances to Charlemagne’s chapel at Aachen, a comparison that Louis was eager to emphasize in order to establish himself as a suitable heir to the first Holy Roman Emperor. The possession of the True Cross and crown of thorns brought immense prestige to the French king.

According to Pope Innocent IV, this signified that Jesus had symbolically anointed the king with his own crown.

13th Century: The Royal Chapel

Sainte Chapelle Cathedral was constructed to contain Louis IX’s treasury of Christ’s relics, which consisted of the Image of Edessa, the Crown of Thorns, and over 30 other artifacts. King Louis paid 135,000 Livres to the Latin emperor of Constantinople, Baldwin II, for his Passion relics. This sum was given to the Venetians who had pawned the artifacts. A couple of Dominican friars brought relics to Paris from Venice in August 1239. When the relics arrived, King Louis held a week-long celebration.

The King personally carried them for the last part of the relics’ journey, barefoot and clothed as a pilgrim, as portrayed in the Relics of the Passion window on the chapel’s south side.

The artifacts were kept in the Grand Chasse, a massive and ornate silver chest. The remains were held in shrines at the Château de Vincennes and another specifically designed chapel at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye until it was finished in 1248.

Pieces of the Holy Lance and the True Cross, as well as other relics, were added to King Louis’ collection in 1246. On the 26th of April, 1248, the chapel was dedicated, and the relics were ceremoniously carried to their new home. Soon after, he embarked on the Seventh Crusade, during which he was kidnapped, ransomed, and freed.

16th – 18th Centuries: Modifications

The chapel was significantly altered during the years that followed. Soon after the chapel was finished, a new two-floor structure, the Treasury of Chartres, was erected on the northern side. It existed until 1783, after which it was razed to make way for the new Palace of Justice.

On the northern side, another structure was erected to function as a sacristy and vestiary, as well as housing for the treasury guardian.

Louis X of France erected a massive enclosed staircase from the courtyard on the southern side to the upper floor in the 15th century. This was destroyed by fire in 1630, reconstructed, and again demolished. Fires at the palace in 1630, as well as 1776, also caused significant damage, particularly to the furnishings, while a flood in the winter of 1690 severely damaged the lower chapel’s painted walls. The bottom level’s original stained glass was dismantled, and the floor was elevated. In the 19th century, Gothic-style windows replaced the old bottom-floor glass.

18th Century: Vandalism During the French Revolution

Sainte Chapelle in Paris, as a notable religious and royal emblem, was a popular target for vandals during the French Revolution. The chapel was converted into a grain storage warehouse, the external royal symbols and sculptures were broken, and the spire was also pulled down.

Some of the stained glass was damaged or scattered, but about two-thirds of the glass remains today; a portion of the original glass has been reinstalled in other windows. The religious relics were distributed, however, some remain as “Sainte Chapelle Cathedral relics” in the Notre Dame de Paris treasury. Several relics, like the Grande Chasse, were smelted for their valuable metals.

19th – 21st Centuries: Restoration Efforts

The top chapel was converted into a storehouse for the Palace of Justice’s documents from 1803 until 1837. The bottom two meters of stained glass were taken out to allow for more working light. Some of the glass was utilized to replace damaged glass in several other windows, and the remaining pieces were sold. Archaeologists, historians, and writers advocated that the cathedral be conserved and reconstructed to its medieval form commencing in 1835.

Major reconstruction work started under King Louis-Philippe in 1840.

Félix Duban was the first to undertake restoration efforts, followed by Émile Boeswillwald and Jean-Baptiste Lassus, with the youthful Eugène Viollet-le-Duc brought in for assistance. The project lasted 28 years and functioned as a training ground for future restorers and archeologists. It stayed true to the early sketches and depictions of the church that had survived. A related effort, the restoration of the stained glass, ran from 1846 to 1855, with the intention of restoring the chapel to its former splendor. It was produced by glass artisans Maréchal de Metz and Antoine Lusson, as well as the designer Louis Steinheil.

In subsequent years, around one-third of the glass was taken out and reinstalled with medieval glass from other sites or with new glass manufactured in the traditional Gothic style. During WWII, the stained glass was taken out and kept in storage. To preserve the glass from the debris and damage caused by wartime bombardment, an exterior varnish coating was applied in 1945. This had progressively gone darker over time, making the fading images even more difficult to distinguish.

A more extensive seven-year restoration project started in 2008, costing around €10 million to restore and maintain all of the stained glass, restore the exterior masonry, and protect and repair some of the statues.

Description of Sainte-Chapelle in Paris

Now that we have explored the history of Sainte Chapelle in Paris, we can take a deeper look at its exterior and interior features. The Royal Chapel is a striking instance of the Gothic architectural style known as “Rayonnant”, which is distinguished by its strong vertical emphasis and sense of weightlessness. It is built squarely on a lower chapel that functioned as a parish church for all residents of the palace, which operated as the seat of administration.

The Exterior of the Sainte Chapelle Cathedral

A modern guest approaching the Royal Palace courtyard would be greeted with a magnificent formal staircase to their right and the northern side and eastern apse to their left. Deep buttresses capped by crocketed gables along the roof line, pinnacles, and enormous windows separated by bar tracery are all classic Rayonnant architectural features. The interior split into lower and upper chapels is clearly indicated on the exterior by a string course, with smaller windows with a characteristic spherical triangle form piercing the lower walls.

Despite its ornamentation, the outside is remarkably basic and austere, without flying buttresses or large sculptures, and providing little indication of the wealth contained within.

In the construction records, no designer-builder is mentioned. It was thought to be the workmanship of Pierre de Montreuil, the master mason, who worked on the restoration of the Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis and finished the southern transept façade of Notre Dame Cathedral in the 19th century. Modern research disputes this claim in favor of Thomas de Cormont or Jean de Chelles, but Robert Branner recognized the hand of an unknown Amiens master mason in the design. Amiens Cathedral’s apsidal chapels, which it recalls in general structure, and the Chapel of Noyon Cathedral, from which it derived the two-floor design, are the Sainte Chapelle’s most evident architectural forebears.

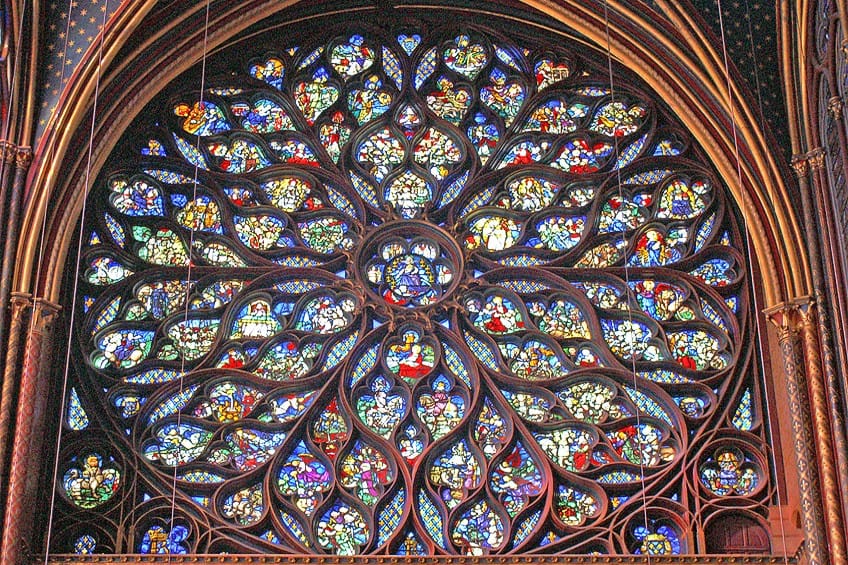

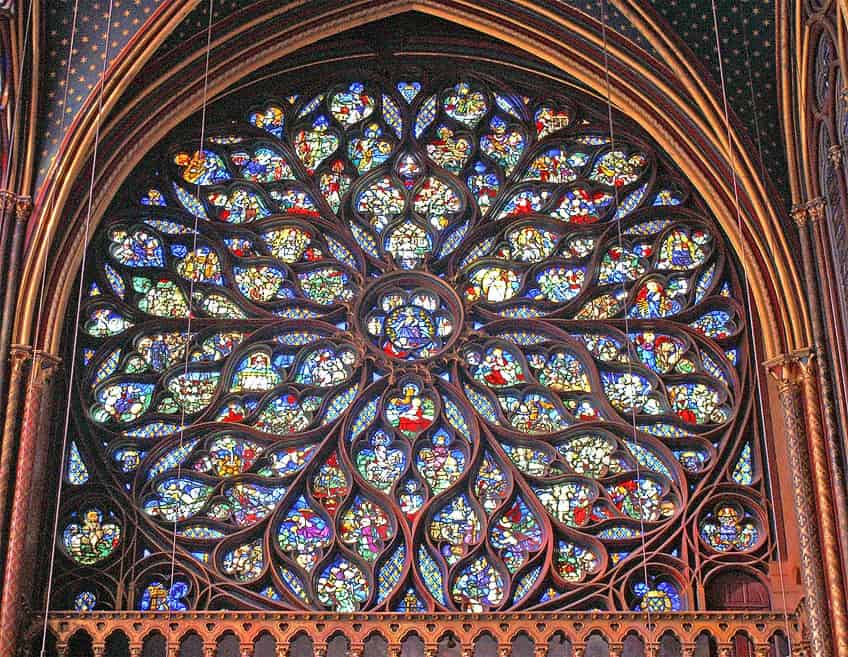

Contemporary metalwork, notably Mosan goldsmiths’ valuable shrines, and holy relics, may have had a significant effect on its overall design. Despite their size, the buttresses are too near to the vault to counteract its side thrust. Metal parts capable of supporting stress, such as chains or iron rods, were utilized to replace prior constructions’ flying buttresses. The western front features a two-story portico beneath a spectacular Gothic rose window built in the 15th century in the upper chapel.

An oculus window at the top and a pointed top, as well as a railing at the bottom of the roof, are ornamented with intertwined fleur-de-lys symbols set by Charles V of France.

Towers on each side of the entrance house the narrow twisting stairways to the top chapel and conceal the buttresses. The tower spires are also adorned with royal fleur-de-lys under a carved crown of thorns. This ornamentation comes from the 15th century and was repaired by Geoffroy-Dechaume around 1850. The upper chapel doorway is positioned on the upper-tier balcony. During the Revolution, the beautiful sculpture of the west gateway was broken and Geoffroy-Dechaume repaired it from 1854 until 1873.

The Spire

The current 33-meter-high spire is the fifth to be constructed since the 13th century. Nothing is known of the first, but the second, erected under Charles V in 1383, is seen in an engraving of the Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. He substituted it about 1460 with another, but it burnt down in 1630. It was superseded by another, which was razed in 1793 as a result of the French Revolution. The current spire was constructed of cedar wood by Lassus the architect starting in 1852. Geoffroy-Dechaume produced the sculptures that adorn the spire in 1853.

The artwork at the foot of the spire was created by painter Steinheil, and his visage emerges as two of the apostles, Saint Bartholomew and Saint Thomas. Just above the gables are sculptures of angels bearing the various instruments of The Passion. A sculpture of Archangel Michael defeating a dragon rises over the chevet. Around the archangel’s feet are statues by Geoffroy-Dechaume depicting eight people, all of whom are reconstruction workers, depositing wreaths at the feet of the Archangel.

The Interior of Sainte Chapelle Cathedral

Saine Chapelle Cathedral, which was intended to hold a reliquary, was like a priceless reliquary inverted, with the richest ornamentation on the interior. Although stained glass dominates the inside, every bit of the leftover wall surface and vault was equally elaborately colored and ornamented. According to the analysis of residual paint particles, the original colors were significantly brighter than those preferred by 19th-century conservators and would have been comparable to the colors of the stained glass.

The dado arcade’s quatrefoils were painted with figures of martyrs and saints and inlaid with colored and gilded glass, replicating Limoges enamels, and lush textile hangings enhanced the interior’s grandeur.

The absence of brick walls in the top chapel is the most remarkable characteristic and distinctive feature of the layout. The walls are substituted with buttresses and pillars, and the area between them is nearly totally glass, allowing light to flood the top chapel. The 15 large stained-glass windows, which originate from the mid-13th century, in addition to the later rose window, are some of the most notable aspects of the chapel and include some of the finest of their kind in the world. The stone wall surface has been reduced to a thin framework. Thousands of little pieces of glass transform the walls into vast screens of colored light, primarily deep reds, and blues that fluctuate in brilliance from hour to hour.

This Holy Chapel, housed within the city’s ancient 13th-century Law Courts, is Paris’ most magnificent Gothic structure. Louis IX designed it to store his private collection of religious relics, which included the famed Holy Crown. The intention was to raise the Kingdom of France to the position of the Western Christian leader. The Sainte Chapelle has been subjected to the ravages of time, experiencing a multitude of transformations. Sainte Chapelle is famous for its vividly colored stained-glass windows, with two-thirds of the windows being unique works that represent the best examples of 12th-century expertise.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where Is the Sainte Chapelle Located?

It is located in the Palais de la Cité, a significant historical building located on an island in the Seine River in Paris. The building in which it was built was the home of various Kings of France for eight centuries. The island itself was an important judicial center as well.

Why Did Louis IX Design the Royal Chapel of Sainte Chapelle With Two Entrances?

One practical purpose was to suit the chapel’s two primary user groups’ differing access requirements. The bottom floor of the chapel was designed for wide public usage and was accessible from the street level. The top floor, on the other hand, was designated for the royal family and was entered by a separate door that led to the royal palace. This division of entrances allowed for more efficient crowd management, while also providing better privacy and protection for the royal family as they entered and exited the chapel. The division of the two entrances mirrored the medieval hierarchical social structure, in which aristocracy and monarchy had greater social standing than commoners. The royal family’s separate entry highlighted their higher social rank, whilst the public’s street-level entrance reaffirmed their inferior social standing.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Sainte Chapelle in Paris – Awe-Inspiring Architecture.” Art in Context. August 21, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/sainte-chapelle-in-paris/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 21 August). Sainte Chapelle in Paris – Awe-Inspiring Architecture. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/sainte-chapelle-in-paris/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Sainte Chapelle in Paris – Awe-Inspiring Architecture.” Art in Context, August 21, 2023. https://artincontext.org/sainte-chapelle-in-paris/.